Abstract

A new MALDI–TOF based detection assay was developed for analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). It is a significant modification on the classic three-step minisequencing method, which includes a polymerase chain reaction (PCR), removal of excess nucleotides and primers, followed by primer extension in the presence of dideoxynucleotides using modified thermostable DNA polymerase. The key feature of this novel assay is reliance upon deoxynucleotide mixes, lacking one of the nucleotides at the polymorphic position. During primer extension in the presence of depleted nucleotide mixes, standard thermostable DNA polymerases dissociate from the template at positions requiring a depleted nucleotide; this principal was harnessed to create a genotyping assay. The assay design requires a primer- extension primer having its 3′-end one nucleotide upstream from the interrogated site. The assay further utilizes the same DNA polymerase in both PCR and the primer extension step. This not only simplifies the assay but also greatly reduces the cost per genotype compared to minisequencing methodology. We demonstrate accurate genotyping using this methodology for two SNPs run in both singleplex and duplex reactions. We term this assay nucleotide depletion genotyping (NUDGE). Nucleotide depletion genotyping could be extended to other genotyping assays based on primer extension such as detection by gel or capillary electrophoresis.

INTRODUCTION

After the complete sequencing of the human genome, the next step is to map its diversity. The most common variations in the human genome are biallelic point mutations called single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). They are also a source of genetic mutation causing disease and the interest in them has multiplied over the last decade (1). Due to rising interest in SNPs, multiple systematic efforts aimed at identifying SNPs have been undertaken, most notably the multi-national effort of the SNP Consortium to discover SNPs and to create a high density SNP map (2). Because the information content of a single SNP in linkage or association studies is less relative to multiallelic markers like microsatellites, wide-scale use of SNP genotyping must rely upon the development of low-cost SNP assays. One of the major SNP genotyping assays has been polymerase-mediated single-base primer extension (minisequencing), which is derived from Sanger DNA sequencing and uses dideoxynucleotides for termination of a growing DNA strand from a primer with its 3′-end designed immediately upstream of a polymorphic site (3,4). Many detection platforms have been used for this assay, including gel and capillary electrophoresis using fluorescent dyes (5), FRET (6), fluorescence polarization (7) and matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (8). Some of the major advantages of using MALDI-TOF for analysis of minisequencing products is the accuracy of the masses from genotyping reactions, being able to analyze multiplexed samples and to ignore background masses that arise for a given sample.

The original assay described for genotyping of SNPs by MALDI-TOF (the PINPOINT assay), relies upon primer extension in the presence of all four dideoxynucleotide triphosphates, and the base at the polymorphic site is identified by the mass added onto the primer. While this is a powerful format for SNP genotyping, there are some disadvantages to the PINPOINT assay format. It is based on addition of dideoxynucleotides, and since the mass difference between the dideoxynucleotides range from a minimum of 9 Da (T and A) up to 40 Da (C and G), the desalting and concentration step is crucial for the analysis of samples with small differences in mass. This is one of the reasons why the original PINPOINT assay (8) has been replaced with so-called ‘NON-PINPOINT’ assays that result in products with substantial mass differences. For example, the assays VSET (9) and PROBE (10,11) utilize a combination of dNTPs and ddNTPs, as well as an assay format that relies upon some form of mass tags on the nucleotides (12). Another disadvantage of minisequencing methods is the cost of the assays which include three or four steps: (i) PCR, (ii) removal of excess nucleotides and primers, (iii) primer extension and (iv) desalting samples for mass spectrometry analysis. These previously described assays require four enzymes including two distinct thermostable DNA polymerases.

We have developed a novel minisequencing method, which is not dependent upon ddNTPs and alleviates the requirement for modified ddNTP incorporating DNA polymerases. Our methodology reduces the complexity compared to the original minisequencing methodology by utilizing a single DNA polymerase. This simplified protocol therefore has a reduced assay cost, thereby increasing the potential for increased SNP genotyping. We demonstrate efficient, robust SNP genotyping using this novel methodology, both in singleplex and duplex reactions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Shrimp alkaline phosphatase (SAP), Exonuclease I (Exo I) and Thermosequenase™ were purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ). AmpliTaq Gold® DNA polymerase was purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Multiscreen384® SNP desalting kits were purchased from Millipore (Bedford, MA). Desalting solutions and matrix were purchased from Sigma. Primers were purchased from MWG Biotech.

DNA isolation and PCR amplification

DNA was isolated using phenol–chloroform extraction from whole blood, as described in Sambrook et al. (13).

The standard PCR protocol was carried out in 10 µl reactions. The reaction mixture contained 40 ng DNA, 1 µM primer mixture, 0.4 U AmpliTaq Gold®, 50 µM dNTPs, Gold buffer and magnesium chloride; standard PCR conditions were used for 35 cycles on MJR thermal cycler. After PCR, the samples were treated with 1 U SAP and 2 U Exo I at 37°C for 30 min followed by heating at 89°C for 15 min. The primers were designed to have Tm 60–65°C by an in-house computer program based on nearest-neighbor methodology (14). Primers for the TSC0033440 (G/C) marker were: PCR_Fwd: d(ATGCCTTTCTCGTGCCATC), PCR_Rev: d(CGTGGTAATAGCAACCAACG), FP_TDI d(TGCCATCCGACCTCCT), Info_Fwd: d(CTCGTGCCATCCGACCTCC) and Info_Rev: d(AAGGTGCAGAGAGTGAAC). Primers for the TSC0920615 marker (G/T) were PCR_Fwd: d(CCACTCCACAACCCTACTGG), PCR_Rev: d(GGACCTGGTTCTTCAGAGCA), FP-TDI_Fwd: d(TGCCAGTGCCTCTTCC), NUDGE_Info_Fwd: d(GTGCCAGTGCCT CTTC) and NUDGE_Info_Rev: d(GGTTCTTCAGAGCAGAGC). Primers for the TSC0834913 marker (C/A) were PCR_Fwd: d(GCATTAAGTTCTGCATCATGTTC), PCR_Rev: d(TGCTTCAGGCATTTTCTTGAT), TDI_Fwd: d(AAGTTCTGCATCATGTTCAGT), NUDGE_Info_Fwd: d(TAAGTTCTGCATCATGTTCAG) and NUDGE_Info_ Rev: d(GCATTTTCTTGATGTTTCAGTAT).

Short PCR reactions using Thermosequenase were done in HEPES buffer (pH 9.4) with 2.5 mM MgCl2, 100 µM dNTPs and 0.4 U Thermosequenase. The primer concentrations were 1 and 2 µM; one primer in 2-fold excess for the NUDGE process (see below). In the course of this work, we refer to primer-extension primers that can generate products specific to each allele as ‘informative’ primers. The PCR program was standard with a very short incubation step. Initial heating step was at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 10 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s and 72°C for 20 s. This was followed by 18 cycles of 89°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s and 72°C for 20 s. Following the PCR the reactions were treated with 1 U SAP at 37°C for 30 min, followed by heating at 85°C for 15 min.

Nucleotide depletion genotyping assay (NUDGE)

For the NUDGE assay on standard Exo I–SAP treated PCR products, we added 0.4 U Thermosequenase, 1 µM informative primer and a combination of dNTPs to extend the informative primer only one nucleotide for allele 1 (to the mutation site by skipping one of the biallelic nucleotides) and two or more nucleotides for allele 2 (onto or over the mutation site), thus terminating the extension at the first position requiring the depleted nucleotide.

When re-using the DNA polymerases from the PCR step, only depleted dNTP mixture was added to a final concentration of 12.5–25 µM after the SAP treatment. The NUDGE assay program was as follows: initial heating step of 89°C for 5 min, followed by 30–40 cycles of 89°C for 30 s, 45°C for 5 s and 65°C for 20 s. With this setup, data for three 96-well plates (markers TSC834913, TSC920615 and duplexed together) were collected simultaneously on the mass spectrometer, using the automatic acquisition setup (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA).

Desalting and MALDI-TOF data acquisition and analysis

The samples were desalted with MultiScreen384 SNP plates following the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, samples were diluted with 10 mM ammonium citrate (pH∼9), filtered and washed prior to re-suspending in MQ water (18MΩ). Either a Hydra 96 (Robbins Scientific, Sunnyvale, CA) or a CyberLab™ (Gilson, Middleton, WI) fluidic station was used for the sample cleanup. The samples were spotted onto an AnchorChip™ (Bruker Daltonics) with a 400 µm anchor. A Constellation 1200™ (Gilson) liquid handler was used to transfer both matrix and sample onto the AnchorChip. This allowed very small volumes (100–500 nl) of sample and matrix to be accurately dispensed. The matrix employed was 7 mg/ml of 3-hydroxypicolinic acid (3-HPA) and 0.7 mg/ml ammoniumcitrate (dibasic). Mass spectra were recorded and analyzed on a Bruker Reflex III that was operated in the linear mode. For automatic acquisition mode, 15 laser shots (three groups of five shots each) were summed up and saved for each sample. The summed spectra for each of the five shots were kept if the measured peak resolution (after smoothing) of the largest peak in the spectra was >200 and the signal/noise ratio was >50.

The data were analyzed with in-house developed software. An in-depth description of the software is beyond the scope of this paper, but, in brief, prior to assigning genotypes, the data were baseline subtracted and smoothed (Savitzky–Golay algorithm using three, five or seven points) (15). Then the data were calibrated using a best-fit method based on observed peaks and their expected values. Only peaks that were initially no more than 25 m/z units away from their expected value were used in the calibration. Observed peaks were then evaluated according to the following criteria: (i) the minimum relative intensity of an extension peak compared to the non-extended primer peak was 0.2; (ii) the maximum m/z difference after calibration was 4 m/z compared to the expected value; (iii) additionally, in the case of heterozygotes, the minimum relative intensity of the two extension peaks was 0.3. A quality value of 1 was assigned to observed peaks that fulfilled all criteria while a quality value of 0.5 was assigned to observed peaks that fulfilled at least one criterion. A quality value of 0 was assigned to observed peaks that did not meet any of the criteria. For each expected peak the observed peak of highest quality was chosen (for peaks with equal quality the peak with greater intensity was chosen). If no suitable peak (i.e. all observed peaks with quality value of 0) was found for an expected peak it was given a no-call status.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The conventional way of designing minisequencing assays is to have the 3′-end of the primer adjacent to the SNP site and extend over the polymorphic site. Extensions with VSET (9) or PROBE (11) methodology then extends one allele one nucleotide and the other allele two or more, using a combination of dNTPs and ddNTPs based on the polymorphic position and the surrounding sequence. The use of a secondary thermostable DNA polymerase, genetically modified to incorporate ddNTPs, has been the standard enzyme utilized in minisequencing, having derived from its use in Sanger DNA sequencing (3). As the thermostability of Thermus-derived DNA polymerases I range well over 1 h at 94°C (16), the DNA polymerase enzymes should remain active after the PCR step and we hypothesized that it could be re-used in a primer extension reaction. We also hypothesized that the DNA polymerases were accurate enough to terminate extension at nucleotides depleted from a mixture since it has been noted that DNA polymerases from family A (Pol I-like) have low processivity and often dissociate from their template (16). We therefore expected nucleotide-dependent termination in linear amplification assays when nucleotide mixtures are depleted of specific nucleotides. It would be possible to design a PINPOINT-style SNP genotyping assay based on these hypotheses if the polymerase could be re-used from the PCR and there is no significant nucleotide misincorporation. In such an assay format, primer extension is done with a nucleotide mixture consisting solely of the two nucleotides present at the polymorphic position rather than a mixture of all four dideoxynucleotides.

Rather than test such a PINPOINT assay, we wanted to design a NON-PINPOINT-style assay format where the two alleles would have a substantial mass difference. To design such a NON-PINPOINT assay, we designed informative primers that end one nucleotide upstream from the polymorphic site and have a nucleotide mixture that is depleted for one of the nucleotides at the polymorphic position. Therefore, when the mixture is depleted for one of the SNP nucleotides one allele product would terminate before the SNP position during the extension reaction, and the other would be extended through the SNP site and would terminate before the next position requiring a depleted nucleotide. The informative primer was designed with its 3′-end one base upstream from the SNP site to allow differentiation between the non-extended primer and the shorter allele. Employing this design we can extend one nucleotide for the SNP allele that is depleted from the nucleotide mixture for a given SNP (the shorter extension product), while the other allele is extended one or more nucleotides over the SNP, until it is terminated at a depleted nucleotide.

Our first experiment was to test whether such informative primers could be extended in this manner on a PCR product that had been depleted of dNTPs and primers by Exo I/SAP incubation. We utilized marker TSC0033440 on three samples representing each of the three possible genotypes that had been previously genotyped by the fluorescence polarization template-directed dye-terminator incorporation assay (FP-TDI) (17). To cleaned PCR product we added 0.4 U Thermosequenase, dNTP (dGTP depleted) mixture to a final concentration of 12.5 and 1 µM Info_Fwd primer. The results are shown in Figure 1. At the outset, our primary concerns were (i) false incorporation of wrong nucleotides at the depleted nucleotide site and (ii) whether the shorter extension product would, in subsequent cycles, anneal to the longer allele templates, resulting in only the longer product on heterozygous target sequence. However, as seen in Figure 1 this is not the case—the extensions are readily terminated and no background or unnatural deviation in the allele ratios is seen. After many cycles, when the concentration of the informative primer runs very low, we have seen a shift in the ratios of the heterozygotes, with a decrease in the relative peak height of the shorter allele. This behavior can be avoided by ensuring that the concentration of the informative primer is not limiting. These results suggest that there is no need for ddNTPs or specific ddNTP incorporating thermostable DNA polymerase for successful SNP genotyping.

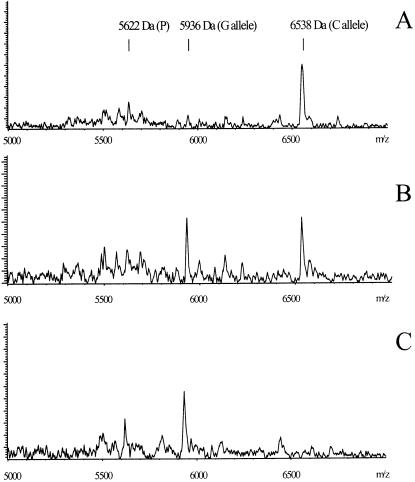

Figure 1.

Marker TSC0033440 (G/C polymorphism) genotyped without ddNTPs, using Thermosequenase, on three DNA samples representing each of the three possible genotypes. Forward informative primer (5663 Da) was used for the primer extension with 12.5 µM dNTP mix depleted of dGTP. The expected primer extension products were 5966 Da (pT extension) and 6559 Da (pTpCpT extension) for the G and C alleles, respectively. (A) Homozygous C/C sample for TSC0033440. (B) Heterozygous G/C sample for TSC0033440. (C) Homozygous sample G/G for TSC0033440.

Subsequently, we wanted to see if the same thermostable DNA polymerase could be used throughout the whole process. The two main groups of commercially available thermostable DNA polymerases are from Thermus species or of Archeal origin and these polymerases have a half-life of >1 h at 94°C. Consequently, we expected significant residual DNA polymerase activity after PCR (15). We again utilized marker TSC0033440 on three samples representing each of the three possible genotypes that had been previously genotyped by FP-TDI (17). After PCR with AmpliTaq Gold and Exo I–SAP treatment we added only dGTP-depleted dNTP mixture to a final concentration of 25 and 1 µM Info_Rev primer followed by 35 thermal cycles as described in Materials and Methods. The results are shown in Figure 2. The results demonstrate that AmpliTaq Gold added at the PCR step can be used for SNP genotyping using NUDGE and therefore there is no need for a modified DNA polymerase in this assay. We have sometimes seen some degradation of the informative primer due to the 5′–3′ exonuclease activity of the AmpliTaq Gold enzyme which can interfere with the results. It would therefore be preferable to use an exonuclease-deficient DNA polymerase, or to modify the informative primers so they would be resistant to the degradation, for example with 5′-thiophosphate groups.

Figure 2.

Marker TSC0033440 (G/C polymorphism). Exo I- and SAP-treated PCR products, genotyped without ddNTPs, re-using AmpliTaq Gold, from the PCR step on three pre-genotyped DNA samples. Reverse informative primer (5622 Da) was used for the primer extension with 25 µM dNTP depleted of dGTP. The expected extension products were 5936 Da (pA extension) and 6538 Da (pApCpA extension) for the C and G alleles, respectively. (A) Homozygous C/C sample for TSC0033440. (B) Heterozygous G/C sample for TSC0033440. (C) Homozygous G/G sample for TSC0033440.

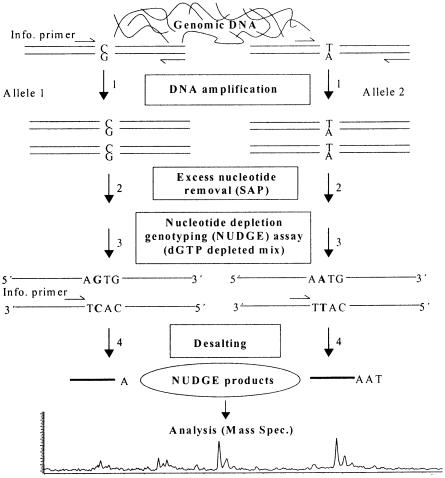

We next designed an assay utilizing the properties demonstrated in the previous experiments to make a simpler SNP genotyping process for the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry platform, which we term NUDGE. Schematic layout of the NUDGE process is shown in Figure 3. In its simplest form, the same primer pair is designed and re-utilized for both PCR and the NUDGE process. Both the upstream and downstream primers are designed with their 3′-ends a single base from the polymorphic position, therefore giving both the potential of being informative. When setting up the PCR, one informative primer is in 2-fold higher concentration relative to the other primer. PCR is done to 20–25 cycles, so that the primers are not exhausted during PCR, excess dNTPs are degraded and the appropriate dNTP mix is added to the reaction. To test the accuracy of the NUDGE assay, we genotyped 94 genomic DNA samples for the markers TSC0834913 and TSC0920615 from the SNP consortium database, both separately and duplexed together, using Thermosequenase DNA polymerase (Fig. 4). The data for the three 96-well (94 samples and two water controls) plates were collected simultaneously on the mass spectrometer and resulted in a total of 243 (85.8%) spectra saved out of a possible 282 spots (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Schematic picture of the NUDGE process. In this example, starting heterozygote target was G/A polymorphism for a given marker. (1) PCR with informative forward primer twice the concentration of the reverse primer resulting in accumulation of small PCR products. (2) Degradation of excess dNTPs using SAP. (3) Genotyping with NUDGE using the existing forward informative primer and dGTP depleted dNTP mixture. (4) Purification of the accumulated extension products to be analyzed by MALDI–TOF mass spectrometry.

Figure 4.

Markers TSC0834913 and TSC0920615 genotyped together (duplex) using the NUDGE protocol and dGTP/dATP depleted mixture. (A) Sample A was homozygous for both markers. TSC0834913 info_Fwd (6412 Da) and A allele (6716 Da), TSC0920615 info_Rev (5541 Da) and T allele (5830 Da). (B) Sample B was homozygous for TSC0834913 A allele (6716 Da) and TSC0920615 homozygous for the G allele (6119 Da); the asterisk-labeled peak had a mass of 5845 Da and did not match the T allele and was excluded in the calibration process. (C) Sample C was heterozygous for the TSC0834913 A (6716 Da) and C alleles (7006 Da) and also for TSC0920615 G (6119 Da) and T alleles (5830 Da). The extra peaks labeled with squares are from the TSC0834913 NUDGE_Info_Rev primer (7026 Da) and its extensions that also interrogate the SNP C (7315 Da) and A alleles (7619 Da). The extra peaks labeled with diamonds are extensions from the TSC0920615 NUDGE_Info_Fwd (4824 Da) primer that also interrogates the SNP T (5114 Da) and G alleles (5418 Da). Since the TSC0834913 NUDGE_Info_Rev and TSC0920615 NUDGE_Info_Fwd were in lower concentration than the other informative primers, the peaks are of lower intensity, but they can be used to confirm the data.

Table 1. Summary of results from genotyping two SNPs by NUDGE.

| Reaction setup | SNP | Acquired spectra | NUDGE automatic calls | NUDGE calls (after manual check) | FP-TDI genotypes for comparison | Mismatches | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality 1 | Quality 0.5 | ||||||

| Singleplex | TSC0834913 | 80 | 64 | 16 | 80 | 74 | 0 |

| Singleplex | TSC0920615 | 83 | 72 | 11 | 81 | 71 | 0 |

| Duplex | TSC0834913 | 80 | 65 | 15 | 78 | 140 | 0 |

| TSC0920615 | 55 | 21 | 75 | 0 | |||

| Total | 243 | 256 | 63 | 314 | 285 | 0 | |

For 94 possible samples, the NUDGE assay was performed on the markers TSC034913 and TSC0920615 separately and in duplex. Summary data are provided for the number of spectra successfully acquired, number of samples with each automatic quality value and the number of genotypes after manual check. Additionally, the number of samples with FP-TDI-based genotypes is provided, as well as the number of observed mismatches.

One of the 96-well plates contained two SNPs that were measured simultaneously, so in total there were potentially 376 SNPs to be genotyped. Of those 376 potential genotypes, 319 genotypable spectra were saved (84.8%) (Table 1). Of those 319, 256 (80.2%) were assigned a quality value of 1, while the remaining 63 (19.8%) were assigned a quality value of 0.5 (Table 1). All SNP calls with a quality value of 0.5 were manually inspected and the assignment of 11 of them was changed from the automatic calling values. Six calls were changed to other genotype values, while the remaining five were changed to no-call. After data analysis and manual inspection the result was that 314 (98.4%) out of the 319 spectra were called (Table 1). Comparison with FP-TDI data resulted in 74, 71 and 140 called genotypes to be compared within the two methods, for markers TSC0834913, TSC0920615 as well as these markers duplexed together. For this analysis 100% concordance was seen with FP-TDI results (Table 1). In the population-based Icelandic samples used in this analysis, we observed the following allele frequencies for these markers: TSC0834913, A 63.3% and C 36.7%; TSC0920615, T 63.0% and G 37.0%.

While we were able to employ both Thermosequenase and AmpliTaq Gold in the NUDGE assay, Thermosequenase gave better results, which is likely due to the lack of exonuclease activity. AmpliTaq Gold showed some 5′-3′ degradation on some of the informative primers but not enough to endanger the quality of the data significantly, although it would make analysis of multiplexed NUDGE assays more difficult. We saw no primer–dimer formation resulting in false primer extension when using Thermosequenase or when we employed PCR without using ‘hotstart’ conditions, since AmpliTaq Gold is chemically modified to be activated in a heating step in its PCR protocol. We hypothesize that other DNA polymerases could be used in NUDGE as long as they have a relatively long half-life at 94°C and, preferably, no exonuclease activity. It is not necessary to have a short PCR product, as sometimes it might be necessary due to sequence composition around the SNP to move one of the primers further away and to have only one informative primer for the NUDGE reaction and analysis.

To extend our findings, and to investigate the general utility of the NUDGE assay, we designed and applied the methodology to a wider set of SNPs. We took 21 SNP markers randomly selected from the SNP consortium, and genotyped them on 12 DNA samples. In these experiments, 19 of the assays gave robust genotypes on the first pass and with standard assay conditions (data not shown). This observation suggests that the NUDGE assay is of general utility, and can be routinely applied for SNP genotyping.

The NUDGE assay suggests a modified format with a single enzymatic incubation. This modified NUDGE assay would consist of a single PCR reaction with one informative primer at 2-fold higher concentration and a dNTP mixture with one or more nucleotides at lower, limiting concentration. With one dNTP at lower concentration, depletion of the nucleotide occurs at later PCR cycles (total of 40–50 cycles) and the reaction switches from PCR to termination dependent upon the genotypes. This could therefore result in a one-step enzymatic genotyping process. Preliminary experiments have demonstrated SNP genotypes at low concentration of dNTP mixtures (data not shown).

Our results demonstrate that NUDGE generates accurate, robust genotypes both in singleplex and duplex format. We anticipate that the NUDGE assay will easily extend to a wide number of SNP markers, and that the assay can be multiplexed to higher levels. The NUDGE assay format allows the reutilization of DNA polymerase for the genotyping reaction instead of modified DNA polymerase typically used in minisequencing reactions. The NUDGE assay is simpler than other SNP single base extension genotyping formats currently analyzed by mass spectrometry. Given the reliance on a single DNA polymerase and a simplified workflow, the NUDGE assay has significant potential as an efficient genotyping assay. Additionally, like other MALDI-TOF-based SNP genotyping formats, the NUDGE assay retains an ability for multiplexing. Multiplexing can be done on this platform, as we have initially demonstrated with duplexed markers. The multiplex feature of the NUDGE assay faces similar limitations to other minisequencing reactions, as the markers have to be selected for multiplex pools based on appropriate termination mixtures. However, this is not likely to be a significant limitation as SNP genotyping studies typically include large number of markers, and therefore markers required in the same mixtures could be pooled together. Additionally, the NUDGE process has the potential to be extended to other primer extension assay detection platforms, including detection by gel or capillary electrophoresis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Risch N. and Merikangas,K. (1996) The future of genetic studies of complex human diseases. Science, 273, 1516–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masood E. (1999) As consortium plans free SNP map of human genome. Nature, 398, 545–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanger F., Nicklen,S. and Coulson,A.R. (1977) DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 74, 5463–5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Syvanen A.C., Aalto-Setala,K., Harju,L., Kontula,K. and Soderlund,H. (1990) A primer-guided nucleotide incorporation assay in the genotyping of apolipoprotein E. Genomics, 8, 684–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pastinen T., Partanen,J. and Syvanen,A.C. (1996) Multiplex, fluorescent, solid-phase minisequencing for efficient screening of DNA sequence variation. Clin. Chem., 42, 1391–1397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X. and Kwok,P.Y. (1997) Template-directed dye-terminator incorporation (TDI) assay: a homogeneous DNA diagnostic method based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 347–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen X., Levine,L. and Kwok,P.Y. (1999) Fluorescence polarization in homogeneous nucleic acid analysis. Genome Res., 9, 492–498. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haff L.A. and Smirnov,I.P. (1997) Single-nucleotide polymorphism identification assays using a thermostable DNA polymerase and delayed extraction MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Genome Res., 7, 378–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun X., Ding,H., Hung,K. and Guo,B. (2000) A new MALDI-TOF based mini-sequencing assay for genotyping of SNPs. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, E68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braun A., Little,D.P. and Koster,H. (1997) Detecting CFTR gene mutations by using primer oligo base extension and mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem., 43, 1151–1158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Little D.P., Braun,A., Darnhofer-Demar,B. and Koster,H. (1997) Identification of apolipoprotein E polymorphisms using temperature cycled primer oligo base extension and mass spectrometry. Eur. J. Clin. Chem. Clin. Biochem., 35, 545–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fei Z., Ono,T. and Smith,L.M. (1998) MALDI-TOF mass spectrometric typing of single nucleotide polymorphisms with mass-tagged ddNTPs. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 2827–2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning, a Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rychlik W. and Rhoads,R.E. (1989) A computer program for choosing optimal oligonucleotides for filter hybridization, sequencing and in vitro amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 8543–8551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savitzky A. and Golay,M.J.E. (1964) Smoothing and differentiation of data by a simplified least squares procedures. Anal. Chem., 36, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perler F.B., Kumar,S. and Kong,H. (1996) Thermostable DNA polymerases. Adv. Protein Chem., 48, 377–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu T.M., Chen,X., Duan,S., Miller,R.D. and Kwok,P.Y. (2001) Universal SNP genotyping assay with fluorescence polarization detection. Biotechniques, 31, 560, 562,, 564–568, passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]