INTRODUCTION

Current epidemiological data suggest that HIV disproportionately affects blacks in the United States, however, few studies have examined HIV trends among the immigrant black population (1, 2). Although Haitian-born persons have been historically stigmatized for introducing HIV to North America (3), no previous study has reported the U.S. national HIV surveillance trends amongst this foreign-born group. This is in stark contrast to the number of scientific reports published on native and foreign-born Hispanic communities that have described the personal and situational risk factors that place them at risk for acquiring HIV (4–11). In addition, reports on Haitians with AIDS have been primarily based on data from the homeland. The World Health Organization reports that Haiti faces the worst AIDS epidemic outside of Africa, and it has the highest prevalence of HIV (2.2%) in the Caribbean and Latin American region (12). Hence, studies describing HIV trends among Haitian-born persons living in the United States are of the utmost importance and long overdue.

In the early 1980s at the beginning of the epidemic, the scientific community did not have an official name for HIV or AIDS (13, 14); however in the general press “the 4H disease” was coined standing for Haitians, Homosexuals, Hemophiliacs, and Heroin users – the the perceived risk factors at the time (15, 16). Reportedly for Haitians, linguistic and cultural issues were barriers to effective communication with caregivers and researchers (16). Historically this was also the period in the U.S. when Haitians were in the limelight seeking political asylum, dying at sea from sinking boats, their bodies washing ashore Florida beaches, with many incarcerated and transferred to immigration detention centers. Similar to other populations at this time some Haitians were diagnosed with a new syndrome. However, Federal officials placed Haitian immigrants in a separate risk category, asserting there was a higher incidence among Haitian-born persons than other groups (17). By 1990 Haitians were removed from the high-risk category because Federal officials recognized a need to eliminate the ban on blood donations based on geographical and national groups. Nevertheless, almost 27 years later a publication in the Proceedings of The National Academy of Sciences concluded that Haiti was the key conduit for the introduction of HIV to the North American continent (3). Despite these ongoing discussions linking Haitians with HIV over the past 20 years no study has previously reported on HIV surveillance trends amongst foreign-born Haitians living in the U.S., although country of birth information has been collected as part of the HIV/AIDS surveillance case report form by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) since 1982 (18).

The primary objective of this paper is to report on the national trends for AIDS diagnoses among Haitian born-persons, and compare those trends to trends for the US population and non-Hispanic blacks. The secondary objective is to identify the major risk factors associated with HIV morbidity in Haitian-born persons, in an effort to provide up-to-date information to medical, mental and public health practitioners working with this population. These data are necessary to tailor culturally sensitive interventions as HIV risk factors may differ substantially between Haitian-born persons and native-born blacks.

METHODS

Data on HIV and AIDS diagnoses reflected herein are from CDC’s national HIV/AIDS Reporting System. Beginning in 1982, all 50 US states and the District of Columbia (DC) reported AIDS cases to the CDC in a uniform format. Since the inception of national AIDS case reporting, the surveillance case definitions for AIDS were based on clinical conditions. With the 1993 expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults, AIDS (HIV infection with AIDS) could also be distinguished from HIV infection without AIDS by a count of CD4+ T-lymphocytes/uL of less than 200 or CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage of total lymphocytes of less than 14. In 1994, CDC implemented data management for national reporting of HIV integrated with AIDS case reporting, at which time 25 states with confidential, name-based HIV reporting started submitting case reports to CDC. Over time, additional states implemented name-based HIV reporting and started reporting these cases to CDC. For the most recent time period (2004–2007), data were available from 34 US states (Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming). All cases were reported to CDC without identifying information. Assessments of duplicate cases occurred both on the state and national level (potential duplicates were identified based on soundex code [a phonetic algorithm for indexing names by sound, as pronounced in English] and selected demographic characteristics), and elimination of such cases occurred at the state level. An assessment of the completeness of case reporting found that more than 80% of AIDS diagnoses and more than 75% of HIV (without AIDS) diagnoses are reported within 12 months after the diagnosis date (19).

We determined trends in the number of AIDS diagnoses in the US for 1985 through 2007 for Haitian-born adults and adolescents. Cases were identified by the designation of “Haiti” as place of birth on the CDC case report form. The majority of Haitian-born persons (HBPs) with AIDS [97%] were classified as non-Hispanic black; therefore, results were not presented by race/ethnicity. Less than 1% [n=88] of AIDS cases diagnosed 1985–2007 of persons born in Haiti were among children less than 13 years of age, and were excluded from these analysis. The number of persons living with AIDS was determined overall for HBPs, and by age group, sex and transmission categories (men who have sex with men [MSM]; injection drug user [IDU]; men who have sex with men and inject drugs [MSM/IDU]; heterosexual contact with a person known to have, or to be at high risk for, HIV infection). The proportional decrease in AIDS cases (after the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy [HAART] to present) was calculated by dividing the number of 1997 cases by 2007 cases, and the construction of the two-sided confidence intervals for the proportion is based on the binomial distribution using a normal approximation (20).

The number of persons diagnosed with HIV (with or without a concurrent AIDS diagnosis) during 2004 through 2007 in the 34 states was examined by age, sex and transmission category. To determine differences in late AIDS diagnosis in the course of disease, we calculated the proportion of persons diagnosed with HIV during 2004 through 2006 who had an AIDS diagnosis within 12 months. All data presented were adjusted for reporting delays and transmission category, using a multiple imputation method for persons reported without an identified risk factor (21).

Rates per 100,000 population were calculated for the numbers of diagnoses of AIDS among HBPs, and by race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native) for all persons diagnosed with AIDS in 2007. The population denominators used to compute AIDS rates by race/ethnicity for the 50 states and the District of Columbia were based on official postcensus estimates for 2007, from the US Census Bureau (22), and bridged-race estimates for 2007 obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics (23). The bridged estimates are based on the Census 2000 counts and produced under a collaborative agreement with the U.S Census Bureau. These estimates result from bridging the 31 race categories used in Census 2000, as specified in the OMB’s 1997 standards for the classification of data on race and ethnicity, to the 4 race categories specified in the 1977 standards and to correspond to the surveillance data. Denominator information to compute rates for HBPs were obtained from data of the American Community Survey (ACS) from the US Census Bureau (24). However, because foreign-born Haitians are considered a “hard-to-count population”, ACS figures may underestimate foreign-born Haitians in the US. Therefore, population estimates for foreign-born Haitians have also been obtained from the Haitian Consulate for comparison (25–27). The latter estimates are based on the number of consular services (e.g., passports, visas, etc) performed for Haitian born-persons throughout the US, and on estimates of Haitians attending events sponsored by the Haitian consulate, in collaboration with community-based organizations serving Haitian-born persons living in the U.S.

Ethics

This project was approved by the institutional review board of the Weill Medical College of Cornell, and at CDC, public health disease surveillance activities are not considered research, and therefore are not subject to human subjects review.

RESULTS

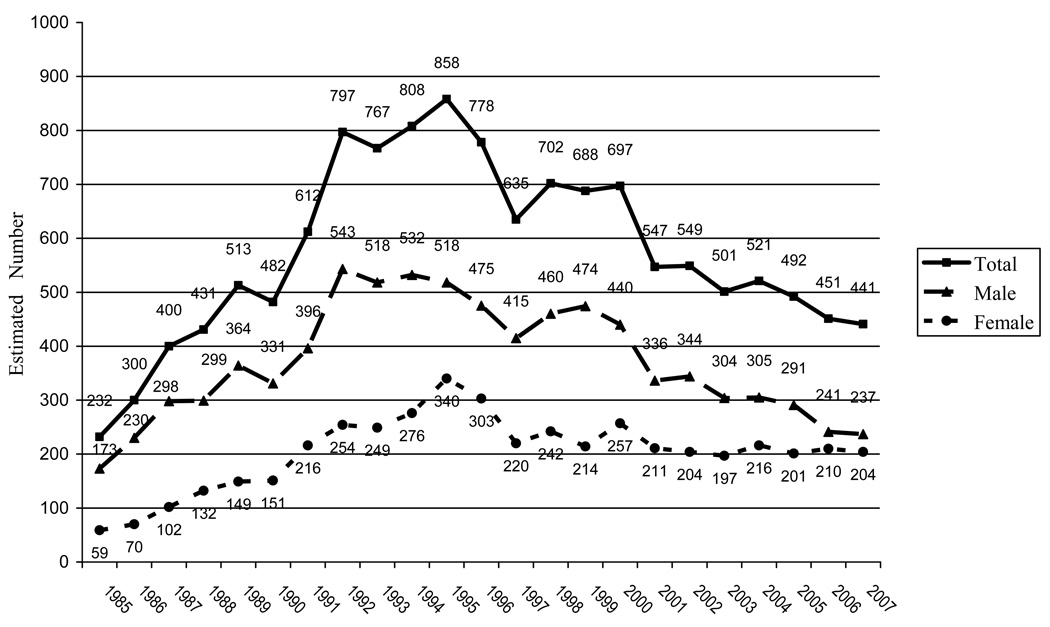

A total of 13,202 Haitian-born adults and adolescents were diagnosed with AIDS during 1985 through 2007 (Table 1). The majority of persons from this population resided in the Southern (62%) or Northeastern (37%) part of the US. Trend analyses showed that AIDS diagnoses within HBPs increased during the 1980s and early 1990s, peaked in the mid 1990s (about 858 AIDS diagnoses in 1995), and subsequently decreased and leveled off in the 2000s, with an estimated 441 AIDS diagnoses in 2007 (Figure 1). Cumulative AIDS diagnoses during the period of 1985–2007 showed that HBPs comprise 1.3% (N=13,202) of the total US AIDS cases (N=998,482) for this time period, and 3.1% of the cumulative AIDS cases among non-Hispanic blacks (N=417,491) reported to CDC (Table 1). Comparisons across gender show there has been a 40% proportional decrease (95% CI=35%-45%) in incident AIDS cases amongst Haitian-born men, compared to a 3% decrease (95% CI=1%-6%) in Haitian-born women over the same time period (Figure 1). Comparisons across racial/ethnic groups show the AIDS rate for HBPs is higher than for non-Hispanic blacks overall (81.6/100,000 vs. 59.2/100,000), using denominator data from the American Community Survey to calculate the AIDS rate for HBPs (Table 1). However, using denominator data from the Haitian Consulates, the AIDS rate for HBPs is lower than that for non-Hispanic blacks, ranging from 34.7 to 46.2 per 100,000 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Estimated numbers of AIDS cases and Rates among Adults and Adolescents by Racial/Ethnic Group, 1985 through 2007, United States

| 1985–2007 Estimated AIDS Cases† among Adults and Adolescents |

% AIDS Cases |

|

|---|---|---|

| White, not Hispanic | 396,435 | 39.7% |

| Black, not Hispanic ∫ | 404,703 | 40.5% |

| Haitian (Foreign-born) § | 12,789 | 1.3% |

| Hispanic ξ | 165,956 | 16.6% |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 7,432 | 0.7% |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 3,452 | 0.3% |

| Total* | 998,482 | 100.0% |

| 2007 Estimated AIDS Cases among Adults and Adolescents |

% AIDS Cases |

2007 Population Data among Adults in the 50 states and the District of Columbia |

Rate/100,000 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White, not Hispanic | 10402 | 28.9% | 169,669,112 | 6.1 |

| Black, not Hispanic∫ | 17,486 | 48.7% | 29,520,707 | 59.2 |

| Haitian (Foreign-born)§ | 416 | 1.2% | 530,897‡ | 78.4 |

| Haitian (Consulate, lower estimate) | 416 | - | 900,000 ψ | 46.2 |

| Haitian (Consulate, upper estimate) | 416 | - | 1,200,000 ψ | 34.7 |

| Hispanic | 6,918 | 19.3% | 33,976,467 | 20.4 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 475 | 1.3% | 10,927,024 | 4.3 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 158 | 0.4% | 1,830,961 | 8.6 |

| Total** | 35,934 | 100.0% | ||

The category "Black, not Hispanic" reflects all persons of African descent including Haitians.

Cases were identified by the designation of “Haiti” as place of birth on the CDC case report form.

Includes persons of unknown race or multiple races and persons of unknown sex. Cumulative total includes 7,003 of persons of unknown race or multiple races. Because column totals were calculated independently of the values for the subpopulations, the values in each column may not sum to the column total.

Includes persons of unknown race or multiple races and persons of unknown sex. Cumulative total includes 418 of persons of unknown race or multiple races. Because column totals were calculated independently of the values for the subpopulations, the values in each column may not sum to the column total.

Rates are based on post-censal estimates unless otherwise noted.

Data is taken from the Census, American Community Survey (ACS). The foreign-born Haitian population reflected in the table above includes all persons who were not US citizens at birth. Foreign-born persons are those who indicated they were either a US citizen by naturalization or they were not a citizen of the United States. Census does not ask about immigration status. The foreign-born population surveyed includes all people who indicated that the United States was their usual place of residence on the Census date. This population includes: immigrants (legal permanent residents), temporary migrants (e.g., students), humanitarian migrants (e.g., refugees), and unauthorized migrants (people illegally residing in the United States).

In 2008 the governmental Ministry for Haitians Living Abroad, Republic of Haiti, estimated there were between 900,000 to 1,200,000 persons of Haitian ancestry living in the U.S. Estimates were based on information provided by Haitian Consulates in the United States; however, it is important to note that Consulates do not run nationally-representative surveys/censuses to estimate/count the size of the Haitian population in the United States. Estimates are generated by the approximated population served, over a period of time, during events sponsored by Consulates. The estimates may, or may not, be limited to foreign-born Haitians and may include persons of Haitian ancestry born-outside of Haiti.

Figure 1.

Estimated Number of AIDS Diagnoses amongst Haitian-born Adults and Adolescents in the United States, by Sex (1985–2007)

By the end of 2007 an estimated 6,928 HBPs were living with AIDS in the U.S (Table 2). More than three-quarters of these persons were between 40 and 64 years old. The mode of HIV infection for 54% of Haitian males occurred through high-risk heterosexual contact, 28% in men who have sex with men [MSM], and 14% occurred through injection drug use [IDU]. Among Haitian females living with AIDS, 88% were exposed through high-risk heterosexual contact, and 9% were exposed through IDU.

Table 2.

Estimated numbers of Haitian-born adults and adolescents living with AIDS at the end of 2007, by selected characteristics, United States

| Males |

Females |

Total |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No | % | No. | % | |

| Age (yrs) | ||||||

| 13—19 | 15 | 0.4 | 13 | 0.5 | 28 | 0.4 |

| 20—29 | 51 | 1.2 | 92 | 3.4 | 143 | 2.1 |

| 30—39 | 450 | 10.6 | 471 | 17.6 | 921 | 13.3 |

| 40—49 | 1617 | 38.0 | 1025 | 38.3 | 2642 | 38.1 |

| 50—64 | 1841 | 43.3 | 917 | 34.3 | 2758 | 39.8 |

| 65+ | 279 | 6.6 | 156 | 5.8 | 435 | 6.3 |

| Transmission category | ||||||

| Male-to-male sexual contact | 1198 | 28.2 | 0.0 | 1198 | 17.3 | |

| Injection drug use | 582 | 13.7 | 244 | 9.1 | 826 | 11.9 |

| Male-to-male sexual contact and injection drug use | 113 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 113 | 1.6 | |

| High-risk heterosexual contact | 2308 | 54.3 | 2349 | 87.8 | 4657 | 67.2 |

| Other | 51 | 1.2 | 82 | 3.1 | 133 | 1.9 |

| Total | 4253 | 100.0 | 2675 | 100.0 | 6928 | 100.0 |

Selected characteristics for HBPs diagnosed with HIV infection between 2004–2007 in 34 states show that a majority (60% of males and 58% of females) are between 30 and 49 years old, with high-risk heterosexual contact as the primary mode of transmission for both females and males; and among males, male-to-male contact accounted for 25% and 6% occurred through IDU exposure (Table 3). Irrespective of transmission risk category, 53% of Haitian-born men (N=663/1,247) received an AIDS diagnosis within 12 months of an HIV diagnosis compared to 42% (N=458/1089) of their female counterparts (χ2=29.0, p <0.001) (Table 4). Analyses by age also show that persons 40 or older were more likely to receive a late HIV diagnosis compared to individuals between ages 13 and 39 years (OR=1.8, 95% CI 1.5–2.2; χ2=51.1, p<0.001).

Table 3.

Estimated numbers of Haitian-born adults and adolescents diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, by selected characteristics, 2004–2007, 34 U.S. States

| Male |

Female |

Total |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Age at diagnosis (yrs) | ||||||

| 13--19 | 13 | 1.1 | 21 | 2.0 | 35 | 1.5 |

| 20--29 | 108 | 9.1 | 170 | 15.5 | 278 | 12.2 |

| 30--39 | 287 | 24.1 | 319 | 29.2 | 606 | 26.5 |

| 40--49 | 431 | 36.1 | 312 | 28.6 | 742 | 32.5 |

| 50--64 | 306 | 25.7 | 232 | 21.2 | 538 | 23.6 |

| 65+ | 47 | 4.0 | 38 | 3.5 | 86 | 3.8 |

| Transmission category | ||||||

| Male-to-male sexual contact | 298 | 25.0 | 298 | 13.0 | ||

| Injection drug use | 73 | 6.1 | 57 | 5.2 | 130 | 5.7 |

| Male-to-male sexual contact and injection drug use | 13 | 1.1 | 13 | 0.6 | ||

| High-risk heterosexual contact | 806 | 67.5 | 1028 | 94.2 | 1834 | 80.3 |

| Other | 3 | 0.3 | 7 | 0.7 | 10 | 0.5 |

| Total | 1193 | 100.0 | 1092 | 100.0 | 2286 | 100.0 |

Table 4.

Estimated distribution of Haitian born adults and adolescents with and without a diagnosis of AIDS within 12 months of diagnosis of HIV infection, by selected characteristics, 2004–2006, 34 U.S. states

| AIDS diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 12 Months after diagnosis of HIV infection |

< 12 Months after diagnosis of HIV infection |

Total | |||

| No. | (%)a | No. | (%)a | No. | |

| Age at diagnosis (yrs) | |||||

| 13--29 | 232 | 70 | 97 | 30 | 329 |

| 30--39 | 353 | 56 | 279 | 44 | 632 |

| 40--49 | 367 | 47 | 418 | 53 | 785 |

| 50--64 | 222 | 44 | 285 | 56 | 507 |

| 65+ | 41 | 50 | 41 | 50 | 82 |

| Transmission category/Male adult or adolescent | |||||

| Male-to-male sexual contact | 150 | 49 | 158 | 51 | 308 |

| Injection drug use | 34 | 45 | 41 | 55 | 75 |

| Male-to-male sexual contact and injection drug use | 6 | 47 | 7 | 53 | 14 |

| High-risk heterosexual contactb | 392 | 46 | 454 | 54 | 847 |

| Otherc | 2 | 49 | 2 | 51 | 4 |

| Subtotal | 584 | 47 | 663 | 53 | 1,247 |

| Female adult or adolescent | |||||

| Injection drug use | 29 | 56 | 23 | 44 | 52 |

| High-risk heterosexual contactb | 598 | 58 | 430 | 42 | 1,028 |

| Otherc | 4 | 47 | 5 | 53 | 9 |

| Subtotal | 632 | 58 | 458 | 42 | 1,089 |

| Totale | 1,216 | 52 | 1,121 | 48 | 2,336 |

Note. These numbers do not represent reported case counts. Rather, these numbers are point estimates, which result from adjustments of reported case counts. The reported case counts are adjusted for reporting delays and missing risk-factor information but not for incomplete reporting.

Data include persons in whom AIDS has developed and persons whose first diagnosis of HIV infection and the diagnosis of AIDS were made at the same time.

Data exclude 1 persons whose month of diagnosis of HIV infection is unknown.

Heterosexual contact with a person known to have or at high risk for HIV infection.

Percentages represent proportions of the total number of diagnoses of HIV/AIDS made during 2003–2006 for the corresponding group (see row entries).

Includes hemophilia, blood transfusion, perinatal, and risk factor not reported or not identified.

Includes hemophilia, blood transfusion, and risk factor not reported or not identified.

Includes 26 persons of unknown race or multiple races. Because column totals were calculated independently of the values for the subpopulations, the values in each column may not sum to the column total.

DISCUSSION

These results represent the first surveillance estimates for HIV cases among Haitian-born persons residing in the United States, with four important findings. First, HBPs comprise 1.2% (N=416 divided by 35,934) of the estimated AIDS cases among adults and adolescents for 2007 (Table 1). Yet, HBPs account for only 0.18% of the total US population (using 2007 ACS data; N=530,897 divided by 301,621,159) which suggests a seven-fold over representation of Haitians in the CDC AIDS surveillance data (1.2% divided by 0.18%). Whereas, amongst the estimated adult and adolescent AIDS cases from the 50 states and the District of Columbia diagnosed during 2007, 48.7% are black/African American (N=17,486 divided by 35,934), and blacks/African Americans account for 12% of the total US population, suggesting a 4-fold over-representation (48.7% divided by 12%) in the CDC AIDS surveillance data (28). However, when population estimates from the Haitian Consulate are used there is a 3 to 4 fold over-representation of HBPs in the CDC AIDS surveillance data (1.2% divided by 0.30% to 0.40%), which is similar to that for blacks/African Americans overall. Population estimates for HBPs (0.30% to 0.40%) are calculated using Consulate estimates of the number of HBPs living in the U.S. which range from N=900,000 to 1,200,000 (divided by 301,621,159, using 2007 ACS data for the U.S. population).

Although data from the American Community Survey are reliable they may reflect an undercount for Haitians living in the United States. While Consulates do not run nationally-representative surveys or censuses to estimate, or count, the number of their nationals living in the United States, their upper estimate of approximately 1.2 million Haitian-born persons living in the US is twice that of the American Community Survey (25–27, 29, 30). Furthermore, the US Census Bureau acknowledges that foreign-born populations are often “hard-to-count” if they are undocumented aliens, which might explain the difference in the population estimates used herein.

Second, compared to the national trends for AIDS diagnoses among the US population and non-Hispanic blacks, the trend amongst Haitians was similar with a peak in the early 1990s, a decline in the HAART era around the turn of the century, and since then a plateau (31). However, important differences are recognized in the HIV risk profile for Haitian men compared to non-Hispanic black men. In the former, the primary transmission category (diagnosed during the period of 2004–2007) is high-risk heterosexual contact (68%), followed by sexual contact with other men (25%), and IDU (6%) (Table 3). This pattern differs from trends in non-Hispanic black men living with HIV, for whom the primary transmission category is sexual contact with other men (51%), followed by IDU (21%) and high-risk heterosexual contact (20%) (1).

One possible explanation for differences describing sexual contact is that greater reporting of male-to-male sexual behavior amongst US born African American men may be due to greater social acceptance (32, 33), whereas machismo is a central feature of masculine expression amongst men from the Latin American region, including Haiti (34). Since little has been previously published on the sexual practices of Haitian men this publication will help to serve as a benchmark to follow the patterns and prevalence of high-risk sexual behaviors in this immigrant group.

In addition, while injection drug use is the second leading cause of HIV infection for African Americans, our results confirm lower transmission through this route amongst HBPs (35, 36), which is consistent with other published findings on Haitians. A recent study on hepatitis C in Haiti reports that only 2% of study participants self-identified as having a prior history of IDU (37); and Marcelin et al., (2005) also report that Haitian youth in Florida express very negative opinions about crack, cocaine and heroin use (38). Therefore, future investigations may be useful to better characterize the protective attitudes and behaviors regarding substance use in Haitians that prevent IDU behaviors and HIV transmission.

Third, there was a greater proportional decrease in the number of incident AIDS cases for Haitian males, compared with females, since the HAART era (Table 3). Possible explanations include i) a gender difference in access to, or adherence to HAART, which is consistent with the literature on women’s differential use of HIV medications (39, 40); or ii) that Haitian women did not modify their sexual behaviors because their perception of HIV risk (and subsequent AIDS) may be obscured by their marital status. Decennial 2000 Census estimates show that at least 70% of all Haitian-born persons living in the US, both male and females, have been married at some time (41). Also, some authors show that foreign-born pregnant women often refuse HIV-testing because they are in monogamous relationships (42), and they perceive their risk of acquiring HIV as low because of their relationship status. Data from the CDC Enhanced Perinatal Surveillance Project (1999–2001) support this hypothesis, showing that among foreign-born HIV-infected pregnant women, 42% are married compared to 16% of their US-born counterparts (43).

Another possible reason for the differential decrease, between Haitian males and females, in incident AIDS cases is explained by the “bisexual bridge” of HIV transmission, which has been speculated for the African-American community linking black MSMs to black heterosexual women. These men are often referred to as being on the “down low” (also known as DL), which defines them as heterosexuals who do not disclose their male-to-male sexual behavior to their female partners (44, 45). In a study conducted on DL-identified MSM in 12 US cities, they were more likely than non-DL-identified men to have had a female sex partner in the prior 30 days, and to have had unprotected vaginal sex (46). Findings from this study also report that DL-identified MSM were less likely to have ever been tested for HIV than were non-DL MSM. Thus Haitian women involved with DL-men might have no knowledge of their sexual partners’ HIV behavioral risk factors, contributing to their lowered perception of HIV risk and decreased likelihood of seeking prevention services.

Little information is available about sexual risk or protective and disclosure practices amongst bisexual Haitian men, and how this behavior may be amendable to intervention (32, 33). What is known however is that the prevalence of bisexuality is reportedly higher in both black and Latino men compared to their white counterparts (47), and Haitian notions regarding masculinity are very similar to Latino men (34, 48). White MSMs are more likely to identify as being “gay,” whereas black and Latino men are less likely to identify as “gay”, join gay-related organizations, read gay-related media (49) or disclose their male-to-male sexual behavior to female partners (50). The literature helps to predict these ethnic differences by explaining that black and Latino men see the gay culture in the US as a white, and sometimes feminine phenomenon, that conflicts with their notions of masculinity (47). Black and Latino men also believe they may have to give up their ethnic identity if they self-identify as being “gay,” including loss of the social support received from their ethnic community; and that their communities will not accept male-to-male sexual behavior (51, 52).

Fourth, study findings also show that Haitian men (53%) are more likely to be diagnosed with AIDS within 12 months after an HIV diagnosis compared to Haitian women (42%); however, when these figures are compared to non-Hispanic blacks overall (38%), HBPs have a higher proportion of late stage diagnosis (Table 2 of the National Surveillance Report (53)). One possible explanation in the difference across gender is that women, in general, use more health care services than men, even after correcting for the use of health care services that are specific for women, such as gynecology (54–57), which may indirectly result in earlier stage HIV diagnoses for women. Additionally, a possible explanation for the differences in late stage diagnosis between HBPs and non-Hispanic blacks may be related to health care insurance because Haitian-born persons who are not US citizens are amongst the most likely to be uninsured, compared to other immigrants living in the US (58) . Hence, the latter may significantly impact health care utilization patterns, resulting in greater emergency room use (59) resulting in later diagnosis.

Recommendations

In light of the study’s findings, we recommend that HIV awareness and prevention efforts be customized for Haitian-born persons on HIV knowledge, behavioral risk factors, antiretroviral adherence (60, 61); as well as prevention services use that encourage seeking routine medical care to reduce late stage diagnosis, particularly in Haitian men. Tailored health communications are necessary for Haitian women who are married, in cohabitating monogamous relationships, and/or pregnant (42, 43). Also, a model for HIV prevention for Haitian MSMs living in the United States is needed and could be adapted from available interventions for black MSMs (33), or adapted from the model for Haitian MSMs living in Haiti, which has already been launched (62).

Limitations

There are several limitations to these analyses. In 2007, 17% of case reports were missing a country or continent of birth, thus it is unknown if there are HBPs among these cases. For the analyses of HIV reports, data from 34 states may not be representative of the whole United States because these states report only 66% of all AIDS cases diagnosed during 2004 through 2007. Data were not available for Massachusetts, which has the third largest number of Haitians residing in the United States according to the Census Bureau (30). Analyses were adjusted for reporting delay and multiple imputation was used to adjust risk for cases reported without a risk factor information (21); these are standard surveillance data adjustments. We also cannot say definitively where foreign-born Haitians became infected, because date of arrival is not collected in HIV surveillance data. Persons may have acquired infection in the home country, during an immigration waiting period after they arrived in the United States, or during travel outside of, rather than in the United States.

CONCLUSIONS

This publication is the first to report on the trends in diagnoses of HIV infection for Haitians living in the United States. Study findings show the importance of having accurate denominators to estimate rates of HIV for the Haitian population. Using estimates from the 2007 American Community Survey, results suggest a seven-fold over-representation of Haitians in the CDC AIDS surveillance data. In contrast, using denominator estimates from the Haitian Consulates, Haitian-born persons in the US, at this time, have a similar AIDS rates to blacks/African Americans overall, which challenges beliefs that Haitian immigrants have a higher prevalence of AIDS than other groups. More to the point, the Haitian community remains steadfast in their beliefs that it is an ill-targeted effort to focus on linking Haitians to the introduction of AIDS in the United States. Rather, scientific methods need to be used to better understand what places Haitians at risk for HIV. Study authors recommend that research is urgently needed to adequately address prevention efforts for this ethnic group.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: During the planning phase of this study, portions of the study design were presented at the Second Annual Conference on Health Disparities at Teachers College, Columbia University, March 9–10th, 2007. Preliminary study findings were presented at the 2008 Annual International HIV/AIDS Research Conference on the Role of Families in Preventing and Adapting to HIV/AIDS, sponsored by the U.S. National Institutes of Mental Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease C. [Accessed August 10, 2009];Fact Sheet: HIV/AIDS Amongst African-American. at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/aa/resources/factsheets/aa.htm. 2009 [cited 2009 August 10]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/aa/resources/factsheets/aa.htm.

- 2.Kent JB. Impact of foreign-born persons on HIV diagnosis rates among Blacks in King County, Washington. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005 Dec;17(6 Suppl B):60–67. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2005.17.Supplement_B.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert MT, Rambaut A, Wlasiuk G, Spira TJ, Pitchenik AE, Worobey M. The emergence of HIV/AIDS in the Americas and beyond. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Nov 20;104(47):18566–18570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705329104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corales RB. Editorial comment: foreign-born Latinos with HIV-AIDS--improving clinical care. AIDS Read. 2007 Feb;17(2):87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelley CF, Hernandez-Ramos I, Franco-Paredes C, del Rio C. Clinical, epidemiologic characteristics of foreign-born Latinos with HIV/AIDS at an urban HIV clinic. AIDS Read. 2007 Feb;17(2):73–74. 8–80, 5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.London AS, Driscoll AK. Correlates of HIV/AIDS knowledge among U.S.-born and foreign-born Hispanics in the United States. J Immigr Health. 1999 Oct;1(4):195–205. doi: 10.1023/A:1021811917532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Painter TM. Connecting The Dots: When the Risks of HIV/STD Infection Appear High But the Burden of Infection Is Not Known-The Case of Male Latino Migrants in the Southern United States. AIDS Behav. 2007 Mar 21; doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klevens RM, Diaz T, Fleming PL, Mays MA, Frey R. Trends in AIDS among Hispanics in the United States, 1991–1996. Am J Public Health. 1999 Jul;89(7):1104–1106. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.7.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy J, Mueller G, Whitman S. Epidemiology of AIDS among Hispanics in Chicago. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996 Jan 1;11(1):83–87. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199601010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diaz T, Buehler JW, Castro KG, Ward JW. AIDS trends among Hispanics in the United States. Am J Public Health. 1993 Apr;83(4):504–509. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.4.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espinoza L, Hall HI, Selik RM, Hu X. Characteristics of HIV infection among Hispanics, United States 2003–2006. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008 Sep 1;49(1):94–101. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181820129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO. [cited 12 April 2010];Haiti: Summary Country Profile for HIV/AIDS Treatment Scale-Up. 2005 Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/HIVCP_HTI.pdf.

- 13.Centers Disease C. Persistent, generalized lymphadenopathy among homosexual males. MMWR - Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 1982 May 21;31(19):249–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallo RC. A reflection on HIV/AIDS research after 25 years. Retrovirology. 2006;3:72. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease C. Opportunistic infections and Kaposi's sarcoma among Haitians in the United States. MMWR - Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 1982 Jul 9;31(26):353–354. 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nachman SR, Dreyfuss G. Haitians and AIDS in South Florida. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1986 Feb;17(2):32–33. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilts PTFDA. Set To Reverse Blood Ban. The New York Times; 1990. (Issue Date: 1990-04-24) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease C. Recommendations and Reports: Mandatory Reporting of Infectious Diseases by Clinicians. MMWR - Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 1990 June 22;39(RR-9):1–11. 6–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall HI, Song R, Gerstle JE, 3rd, Lee LM. Assessing the completeness of reporting of human immunodeficiency virus diagnoses in 2002–2003: capture-recapture methods. Am J Epidemiol. 2006 Aug 15;164(4):391–397. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pagano M, Gauvreau K. Principles of biostatistics. 2nd ed. Australia ; Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrison KM, Kajese T, Hall HI, Song R. Risk factor redistribution of the national HIV/AIDS surveillance data: an alternative approach. Public Health Rep. 2008 Sep–Oct;123(5):618–627. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Census Bureau US. Population estimates: entire data set. July 1, 2007. [Accessed December 20, 2008];Department of Commerce EaSA, editor. 2008 http://www.census.gov/popest/estimates.php. Published August 21, 2008.

- 23.NCHS. National Center for Health Statistics; Bridged-race vintage postcensal population estimates for July 1, 2000–July 1, 2007, by year, county, single-year of age, bridged-race, Hispanic origin, and sex. 2007 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/dvs/popbridge/datadoc.htm#vintage2007.

- 24.Grieco E, Humes K. Personal Communication regarding the Foreign-born population of African-descent living in the United States. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Augustin F. Personal Communication with the Consul General. New York, NY: Haitian Consulate of New York; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geneus J. Personal Communication with the Minister of Haitians Living Aboad. Port-au-Prince, Haiti: Republic of Haiti; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jospitre A. Personal Communication with the Consul General. Miami, Florida: Haitian Consulate of Miami; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease C. [Accessed August 10, 2009];HIV/AIDS Surveillance - General Epidemiology (through 2006) 2007 at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/slides/epidemiology/index.htm. [cited 2009 August 10 ]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/slides/epidemiology/index.htm.

- 29.Metayer N, Jean-Louis E, Madison A. Overcoming historical and institutional distrust: key elements in developing and sustaining the community mobilization against HIV in the Boston Haitian community. Ethn Dis. 2004 Summer;14(3 Suppl 1):S46–S52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newland K, Grieco E. [cited 2005 July 27];Spotlight on Haitians in the United States 2004. Available from: http://www.migrationinformation.org/USfocus/display.cfm?ID=214.

- 31.Centers for Disease C. [Accessed August 10, 2009];Slide Sets: AIDS Surveillance Trends 1985–2006. Reference Slide 3. 2006 at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/slides/trends/index.htm. [cited 2009; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/slides/trends/index.htm.

- 32.Dodge B, Jeffries WLIV, Sandfort TG. Beyond the down low: Sexual risk, protection, and disclosure among at-risk Black men who have sex with both men and women (MSMW) Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008 Oct;Vol 37(5):683–696. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9356-7. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones KT, Gray P, Whiteside YO, Wang T, Bost D, Dunbar E, et al. Evaluation of an HIV prevention intervention adapted for Black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2008 Jun;98(6):1043–1050. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sara-Lafosse V. Machismo in Latin America and the Caribbean. New York, New York: Garland Publishing; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halsey NA, Coberly JS, Holt E, Coreil J, Kissinger P, Moulton LH, et al. Sexual behavior, smoking, and HIV-1 infection in Haitian Women. JAMA. 1992 Apr 15;267(15):2062–2066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Risk factors for AIDS among Haitians residing in the United States. Evidence of heterosexual transmission. The Collaborative Study Group of AIDS in Haitian-Americans. JAMA. 1987 Feb 6;257(5):635–659. doi: 10.1001/jama.1987.03390050061019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hepburn MJ, Lawitz EJ. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C and associated risk factors among an urban population in Haiti. BMC Gastroenterol. 2004 Dec 14;4:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-4-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marcelin LH, Vivian J, DiClemente R, Shultz J, Page J. Trends in Alcohol, Drug and Cigarette Use Among Haitian Youth in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2005;4(1):105–131. doi: 10.1300/J233v04n01_07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sayles JN, Wong MD, Cunningham WE. The inability to take medications openly at home: does it help explain gender disparities in HAART use? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006 Mar;15(2):173–181. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mocroft A, Gill MJ, Davidson W, Phillips AN. Are there gender differences in starting protease inhibitors, HAART, and disease progression despite equal access to care? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000 Aug 15;24(5):475–482. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200008150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Census Bureau US. People Born in Haiti - Profile of Selected Demographic and Social Characteristics; Tables FBP-1, FBP-2. Census 2000 Special Tabulations (STP-159) Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aynalem G, Mendoza P, Frederick T, Mascola L. Who and why? HIV-testing refusal during pregnancy: implication for pediatric HIV epidemic disparity. AIDS Behav. 2004 Mar;8(1):25–31. doi: 10.1023/b:aibe.0000017523.39818.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel-Larson A. Data from the Enhanced Perinatal Surveillance Project, 1999–2001. Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2006. Personal Communication. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malebranche DJ. Bisexually active Black men in the United States and HIV: Acknowledging more than the "Down low". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008 Oct;Vol 37(5):810–816. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9364-7. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frieden L. Invisible lives: Addressing the Black male bisexuality in the novels of E. Lynn Harris. Journal of Bisexuality. 2002;Vol 2(1):75–90. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolitski RJ, Jones KT, Wasserman JL, Smith JC. Self-Identification as "Down Low" Among Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) from 12 US Cities. AIDS and Behavior. 2006 Sep;Vol 10(5):519–529. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9095-5. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sandfort TG, Dodge B. "…And then there was the down low": Introduction to Black and Latino male bisexualities. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008 Oct;Vol 37(5):675–682. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9359-4. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smallman SC. The AIDS pandemic in Latin America. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Millett G, Malebranche D, Mason B, Spikes P. Focusing "down low": bisexual black men, HIV risk and heterosexual transmission. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005 Jul;97(7 Suppl) 52S–59S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kalichman SC, Roffman RA, Picciano JF, Bolan M. Risk for HIV infection among bisexual men seeking HIV-prevention services and risks posed to their female partners. Health Psychology. 1998 Jul;17(4):320–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ward EG. Homophobia, hypermasculinity and the US black church. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2005;7:493–504. doi: 10.1080/13691050500151248. 5, Sep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fullilove MT, Fullilove RE., III Stigma as an obstacle to AIDS action. American Behavioral Scientist. 1999;42:1117–1129. 7, April. [Google Scholar]

- 53.CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. Volume 17, Revised. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koopmans GT, Lamers LM. Gender and health care utilization: the role of mental distress and help-seeking propensity. Soc Sci Med. 2007 Mar;64(6):1216–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ladwig KH, Marten-Mittag B, Formanek B, Dammann G. Gender differences of symptom reporting and medical health care utilization in the German population. Eur J Epidemiol. 2000 Jun;16(6):511–518. doi: 10.1023/a:1007629920752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Corney RH. Sex differences in general practice attendance and help seeking for minor illness. J Psychosom Res. 1990;34(5):525–534. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(90)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Briscoe ME. Why do people go to the doctor? Sex differences in the correlates of GP consultation. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25(5):507–513. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carrasquillo O, Carrasquillo AI, Shea S. Health insurance coverage of immigrants living in the United States: differences by citizenship status and country of origin. Am J Public Health. 2000 Jun;90(6):917–923. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.6.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sanchez JP, Hailpern S, Lowe C, Calderon Y. Factors associated with emergency department utilization by urban lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. J Community Health. 2007 Apr;32(2):149–156. doi: 10.1007/s10900-006-9037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reynolds NR, Testa MA, Marc LG, Chesney MA, Neidig JL, Smith SR, et al. Psychosocial influences of attitudes and beliefs toward medication adherence in HIV+ persons naïve to antiretroviral therapy: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of AIDS and Behavior. 2004 June;8(2):141–150. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000030245.52406.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marc LG, Testa MA, Walker AM, Robbins GK, Shafer RW, Anderson NB, et al. Educational attainment and response to HAART during initial therapy for HIV-1 infection. J Psychosom Res. 2007 Aug;63(2):207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Genece E. Peronsal Communication with Executive Director of POZ (Promoteurs Objectif Zero SIDA) Port-au-Prince, Haiti: 2008. Jan, [Google Scholar]