Abstract

Extinction therapy has been proposed as a method to reduce the motivational impact of drug-associated cues to prevent relapse. Cue extinction therapy, however, takes place in a novel context (e.g., treatment facility), and is unlikely to be effective due to the context specificity of extinction. We tested the hypothesis that d-cycloserine (DCS), which enhances extinction in other procedures, would enhance extinction of cocaine-associated cues in a novel context to reduce cue-induced reinstatement. Male Sprague Dawley rats were trained to self-administer cocaine associated with a cue. The cue was later extinguished in the drug-taking context (context A) or a novel context (context B) using a Pavlovian cue extinction procedure designed to mimic human cue exposure therapy. DCS was administered systemically or into a specific brain region immediately following the cue extinction sessions to enhance the consolidation of extinction learning. We demonstrate that DCS given postextinction session in context B reduces reinstatement in context A, indicating a reduction in the context specificity of extinction learning. The effect of systemic DCS was recapitulated by administration of DCS into the nucleus accumbens core, but not in the basolateral amygdala, dorsal hippocampus, infralimbic or prelimbic prefrontal cortex. DCS treatment caused a reduction in cue-induced reinstatement only when it was given after cue extinction sessions, and not when given 1) in the absence of extinction or 2) after a brief memory reactivation session. A pharmacological method that can render extinction context independent may provide an innovative method to reduce cue-induced relapse in addicts and to study the neurobiology of addiction.

Introduction

Drug addiction is a chronic relapsing disorder, consisting of periods of abstinence followed by relapse to drug use, often initiated by exposure to drug-associated cues (Shaham et al., 2003). Extinction of drug-associated cues has been proposed as a means of reducing the motivational properties of cues to prevent relapse (O'Brien et al., 1990; Taylor et al., 2009). Extinction is an active process where an organism learns that a stimulus is no longer predictive of reward, and therefore, future presentations of the stimulus no longer produce behaviors to seek that reward. Extinction does not cause “forgetting” of the original stimulus–reward relationship (Bouton, 2004). Extinction can reduce responses to drug cues, but clinical studies using extinction therapy have reported little success (Conklin and Tiffany, 2002). The ineffectiveness of extinction therapy is likely due to the context dependence of extinction (Bouton and King, 1983; Kearns and Weiss, 2007), such that when extinction therapy is conducted in a clinical setting, it is not likely to transfer to the drug-taking context to prevent cue-induced relapse.

A pharmacological enhancement of the consolidation of extinction memory is one mechanism by which the context specificity of extinction might be reduced. The NMDA receptor partial agonist d-cycloserine (DCS) has been used as an adjunct to exposure therapy in phobic individuals where reductions in fear were later observed in both the clinic and in the “real world” suggesting that extinction can be enhanced pharmacologically and made context independent, possibly to treat addiction (Ressler et al., 2004). However, to date, no investigation has determined whether DCS can reduce the context specificity of extinction of drug-associated cues. Notably, preclinical studies using the conditioned place preference paradigm have demonstrated that DCS can enhance extinction of a cocaine-associated contextual memory when testing occurs in the same context (Botreau et al., 2006; Paolone et al., 2009; Thanos et al., 2009). In addition, DCS facilitates extinction of lever pressing for cocaine in rats and inhibits reacquisition of cocaine self-administration in rats and monkeys (Nic Dhonnchadha et al., 2010). Further, d-serine (a more efficacious NMDAR agonist) facilitates extinction of lever pressing to reduce cocaine-primed reinstatement in rats (Kelamangalath et al., 2009). Therefore, DCS may be useful for enhancing extinction of drug-associated memories to prevent relapse, but it is critical to determine whether DCS can reduce the context dependency of extinction of drug memories (i.e., inhibit renewal).

The present study was designed to determine whether DCS could produce a context-independent enhancement of the consolidation of extinction learning using Pavlovian (noncontingent) cue extinction as a new preclinical model of cue exposure therapy. In addition, we determined the brain loci responsible for the effect of DCS on cue extinction. Moreover, due to the potential ability of DCS to enhance reconsolidation of drug memories (Lee et al., 2009), rather than extinction, we also determined the effect of intranucleus accumbens DCS on reconsolidation of a briefly reactivated cocaine cue memory.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Male Sprague Dawley rats weighing 250–325 g upon delivery (Charles River) were used for all experiments. A total of 201 rats were obtained for these experiments, but 33 were excluded from analysis due to death or illness from surgery, lack of acquisition of cocaine self-administration, inability to extinguish lever pressing, or placement of intracranial cannulae outside of the targeted brain region. Thus, a total of 168 rats were included in the data analysis for all experiments. Rats were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room on a 12:12 h light-dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water except for periods of food restriction described below. Animal procedures conformed to the policies of the Yale University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the National Institutes of Health Guidelines on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Drugs.

Cocaine hydrochloride (provided by National Institute on Drug Abuse, Research Triangle Park, NC) was dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline and filtered for self-administration. d-Cycloserine (DCS; Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared fresh daily in sterile 0.9% saline.

Surgical procedures.

Rats were anesthetized with a combination of 87.5 mg/kg ketamine and 5 mg/kg xylazine. Rats were administered 5 ml of lactated Ringers solution, and 5 mg/kg of the analgesic Rimadyl before implantation with intracranial cannulae and/or indwelling jugular catheters (CamCaths) as described previously (Torregrossa and Kalivas, 2008). In some animals, intracranial cannulae (22 gauge; Plastics One) were implanted bilaterally dorsal to several brain regions using the following coordinates according to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (2005) given in millimeters with reference to bregma: nucleus accumbens core (NAc), anteroposterior (AP): +1.6, mediolateral (ML): ±1.5, dorsoventral (DV): −6.0; dorsal hippocampus (DH), AP: −3.7, ML: ±3.0, DV: −1.6; lateral amygdala (including basolateral region) (LA), AP: −3.0, ML: ±5.3, DV: −7.9; infralimbic and prelimbic prefrontal cortex (IL or PL PFC), AP: +2.7, ML: ±0.5, DV: −1.4. Obturators were inserted in the guide cannulae to maintain patency.

Drug infusions.

In experiments involving brain-specific infusions, DCS was given at a total dose of 10 μg/side in a volume of 0.3 μl for the IL and PL PFC and 0.5 μl for the LA, NAc, and DH. The dose is based on a dose that is reported to both facilitate extinction and reconsolidation of fear when given in the LA (Lee et al., 2006). Infusions were given by removing obturators and inserting injection cannulae (28 gauge; Plastics One) that extended 1 mm beyond the guide cannulae for all regions except for the PFC, where PL injectors extended 3.0 mm and IL injectors extended 4.0 mm beyond the guides to avoid cannulation damage to dorsal regions of the PFC. The injectors were connected to Hamilton syringes controlled by a syringe pump via polyethylene tubing. Infusions were given over 2 min and injectors were left in the cannulae for an additional 2 min to allow for drug diffusion. Vehicle control groups received infusions of sterile 0.9% saline.

Experimental design.

Specific details of behavioral procedures are described in separate sections below. In overview, rats were trained to self-administer cocaine where each infusion was accompanied by a compound cue (CS+, tone+light). After acquisition of stable self-administration, animals went into the lever extinction phase of the experiment, where the instrumental lever response produced neither the cue nor a cocaine infusion. Lever extinction was conducted to reduce lever responding so that we could later test cue-induced reinstatement of lever pressing; however, extinction of levers is NOT the extinction that is targeted for manipulation in these studies. Rather, we specifically extinguished the cue in separate sessions in a Pavlovian (noncontingent) manner, akin to common forms of cue exposure therapy conducted in humans that involves viewing cues without overt instrumental actions. Cocaine self-administration and lever extinction were conducted in a distinct context, heretofore referred to as context A, which represents the drug-taking context (analogous to the “real world”).

After lever extinction training, rats were divided into several groups to determine the ability of Pavlovian cue extinction alone, or in combination with DCS, to reduce later cue-induced reinstatement. The cue extinction sessions were conducted either in context A or in a novel context (context B). Two groups experienced Pavlovian cue extinction in context A followed immediately by a subcutaneous injection of vehicle or 15 mg/kg DCS, and are denoted as either “context A-Veh” (for the vehicle-treated group) or “context A-DCS” (for the DCS-treated group). Likewise, two different groups of rats underwent Pavlovian extinction in context B, and immediately following these sessions received either vehicle or 15 mg/kg DCS. Finally, some animals had no Pavlovian extinction training to serve as a control for the effect of the extinction procedure and are denoted as the “No Cue Ext-Veh” and “No Cue Ext-DCS” groups. This group was placed in context B for the same amount of time as the Pavlovian cue extinction groups, but no cues or other stimuli were presented, thus, controlling for handling and time spent in the operant chamber, but without extinction of the cues. Immediately following the 30 min session, this group received an injection of vehicle or 15 mg/kg DCS.

In the studies involving brain region-specific manipulations of DCS, we conducted cue extinction in context B only, with postsession infusions of DCS or vehicle. All groups were tested 24 h after the last cue extinction session for cue-induced reinstatement in context A. We expected that Pavlovian cue extinction would reduce the motivational value of the cue, such that cues would elicit less reinstatement of lever pressing than in animals that had no cue extinction. In addition, we expected that extinction of the cues in context B would not be sufficient to reduce reinstatement in context A because of the context dependence of extinction, but that pharmacological enhancement of extinction with DCS in context B could reduce the context dependence of extinction.

Cocaine self-administration procedures.

Rats were trained to self-administer cocaine using standard procedures. Rats were maintained at 90% of their free-feeding body weight, receiving ∼20 g of chow per day, and procedures were conducted in standard operant conditioning chambers (Med-Associates). The chambers consisted of a metal grid floor, two retractable levers located on one wall of the chamber, a tone-generator, stimulus-light, and infusion pump. Rats were allowed to self-administer 0.5 mg/kg/infusion cocaine during daily sessions for 1 h or until 60 infusions were obtained, whichever came first, on a fixed ratio 1 (FR1) schedule of reinforcement with a 10 s timeout. Responding on the active lever produced a cocaine infusion paired with a 10 s tone-light cue. Responses on the other, inactive, lever were recorded but had no programmed consequences. Rats were trained for at least 10 d and until they self-administered at least 8 infusions/d over 2 consecutive days, which required 12 d of training in many rats (Fig. 1).

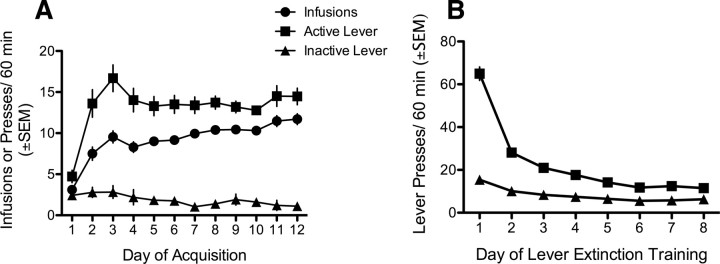

Figure 1.

Cocaine self-administration and lever extinction training data averaged across all experiments. A, Cocaine self-administration training in context A, representing average infusions, active, and inactive lever presses across experiments. B, Lever extinction training in context A, representing average active and inactive lever presses across experiments (n = 168).

Lever extinction.

Rats that successfully acquired self-administration underwent instrumental lever extinction. Lever extinction consisted of daily 1 h sessions where lever presses had no programmed consequences. Lever extinction continued until the number of lever presses was reduced to an average of <25 lever presses on the last two consecutive days of extinction. For the majority of rats the lever extinction criteria was reached in 8 d or less (as depicted in Fig. 1), but a few rats required up to 11 d of lever extinction to reach criteria (data not shown). Rats who did not extinguish lever pressing to this level within 11 d were not included in cue reinstatement analysis. Lever extinction was conducted to reduce responding to a stable, low rate to later assess cue-induced reinstatement. Critically, if lever responses are not extinguished, it is impossible to assess cue-induced reinstatement, as reinstatement is defined as the resumption of a previously extinguished behavior (Shaham et al., 2003). In addition, lever extinction reduces the role of the context and lever presentation in motivating behavior to better isolate the role of the conditioned cue in controlling reinstatement. Lever extinction does not affect the primary goal of the experiment, which is to use Pavlovian extinction to extinguish the conditioned cue in the same or a different context.

Pavlovian cue extinction.

Pavlovian cue extinction occurred over 2 d following the last lever extinction day. During Pavlovian extinction, animals were either placed into the operant conditioning chamber used for self-administration and lever extinction (context A) or in novel operant conditioning chambers that were different in size, flooring texture, shape, and smell (context B). Contexts A and B were the same for all subjects because the self-administration equipment was only available in one type of operant chamber that had to serve as context A in all experiments for all subjects. In both contexts, there was no opportunity for instrumental responding during Pavlovian extinction, i.e., the levers were retracted. The Pavlovian extinction sessions were identical in each context and consisted of 30 min sessions where the 10 s tone-light cue was presented 2×/min for a total of 60 cue presentations/d. Immediately following both cue extinction sessions, 15 mg/kg DCS or vehicle was injected subcutaneously, or 10μg/side DCS intracranially to specifically enhance consolidation of extinction and avoid effects on acquisition of extinction or other state-dependent learning effects that could occur with presession administration. In some pilot studies not presented here, we found that 60 or fewer cue presentations did not produce sufficient extinction to reduce cue-induced reinstatement when extinction and testing occurred in the same context. Moreover, >120 cue presentations did not produce a further reduction in cue-induced reinstatement, indicating a possible floor effect after the amount of extinction training given in these studies, though only if testing occurred in the same context.

Memory reactivation.

To determine whether the effects of DCS on extinction memory consolidation were specific to extinction learning, as opposed to an effect of DCS on memory reconsolidation or other nonspecific motivational processes, we also determined the effect of DCS when given after a brief memory reactivation. This group of rats underwent a single memory reactivation session in context B, where the cocaine-associated cue was presented for 10 s, 3 times, with each presentation separated by 1 min. Immediately following the reactivation session, vehicle or DCS was infused into the NAc. Three presentations of the cue has been shown by previous studies in our laboratory to reactivate the cocaine cue memory such that the memory is then reconsolidated in an amygdalar PKA-dependent manner, without producing extinction (Sanchez et al., 2010).

Cue-induced reinstatement.

Cue-induced reinstatement in context A is the primary measure of the effectiveness of Pavlovian cue extinction to reduce relapse-like behavior (context A extinguished groups) and to determine whether DCS can enhance extinction in a “treatment context” so it transfers to the drug-taking context (context B extinguished groups). The day after the last Pavlovian cue extinction session (or no extinction or reactivation session), cue-induced reinstatement was assessed during a 1 h session in context A. In this session, lever presses produced the cocaine-associated cue on an FR1 schedule, but no other reinforcement.

Histological analysis.

After the completion of experiments, animals with intracranial cannulae were anesthetized, and thionin dye was infused into the brain region at the same volume used experimentally. Rats were then killed by decapitation and their brains were dissected and placed into 10% formalin for at least 3 d. Brains were then transferred to 30% sucrose for at least 3 d. Brains were then frozen and sectioned through the targeted brain region on a cryostat. Sections were taken at 40 μm and placed on slides for visualization of infusion placements. Animals with infusions outside of the specified region were discarded from analysis.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 4.00 for Windows. Reinstatement tests were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures with the within-subjects factor being responding on the last day of lever extinction versus reinstatement responding and the between-subjects factor being the cue extinction treatment. Significant effects were further analyzed by Bonferroni's post hoc t tests, with significance set at p < 0.05.

Results

Figure 1 illustrates the acquisition and lever extinction training data collapsed across all of the experiments for the average number of days required for the majority of rats to meet acquisition and lever extinction criteria. All experimental groups were matched based on their acquisition and lever extinction behavior, such that there were no statistically significant differences between comparison groups on any of these measures before experimental manipulation.

Experiment 1: effects of systemic DCS on Pavlovian extinction in different contexts

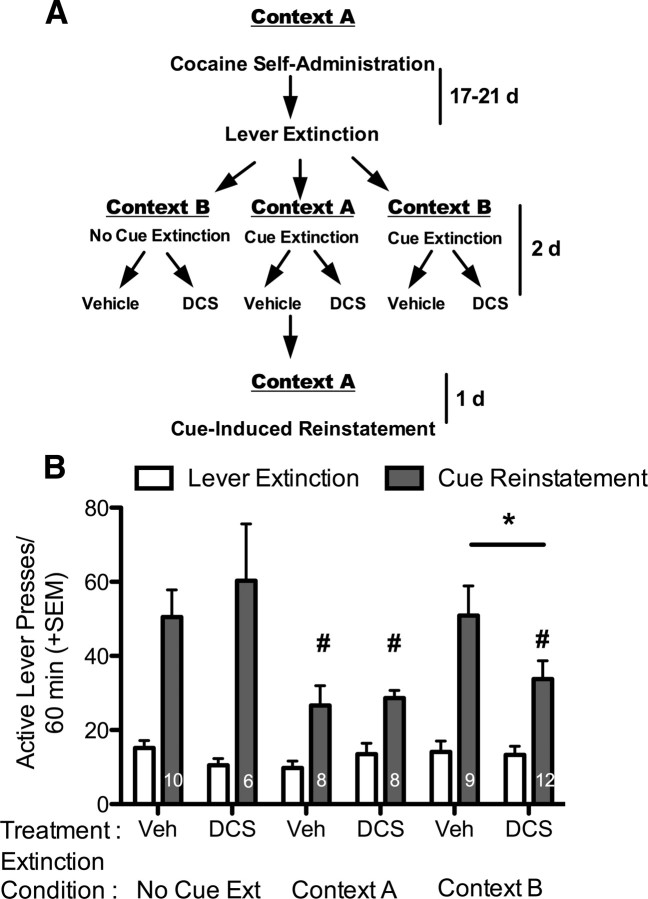

After cocaine self-administration, lever extinction, and Pavlovian extinction training, rats were tested for cue-reinstatement in context A (Fig. 2A, represented schematically). There was no significant difference between the groups in the number of active or inactive lever presses during acquisition, cocaine infusions acquired, nor in the number of responses made during lever extinction. The results of the cue-induced reinstatement test demonstrate a significant effect of reinstatement on active lever responding compared with the last day of lever extinction (F(1,47) = 91.62, p < 0.0001), a significant effect of extinction condition (F(5,47) = 3.02, p = 0.019), and a significant interaction (F(5,47) = 3.04, p = 0.019). Post hoc analysis revealed that there was no significant cue-induced reinstatement, as indicated by a difference in responding on the reinstatement test day compared with responding on the last day of lever extinction, in the context A extinguished rats. Reinstatement responding in the context B-DCS group was not significantly different from the context A groups and was significantly less than the context B-Veh group (p < 0.05), suggesting that DCS reduced the context specificity of cue extinction to attenuate cue reinstatement responding (Fig. 2B). Both of the no cue extinction (No Cue Ext) groups showed significant cue-induced reinstatement responding with no effect of DCS, indicating that DCS is only effective in reducing reinstatement when it is given in conjunction with extinction learning, and is not nonspecifically altering behavior in the reinstatement test. There were no statistically significant differences between groups on inactive lever responding (data not shown).

Figure 2.

DCS produces a context-independent Pavlovian extinction of a cocaine-associated cue. A, Diagram representing the experimental paradigm. B, Cue-induced reinstatement in context A. Cue-induced reinstatement responding is compared with the average responding on the last day of lever extinction (before treatment) for each respective cue extinction treatment group. Both context A extinguished groups showed significantly less cue-induced reinstatement than the No Cue Ext and context B-Veh groups, while the context B-DCS group reinstated significantly less than the context B-Veh group, indicating that DCS produced a context-independent cue extinction to reduce reinstatement. DCS had no effect when it was given in the absence of extinction learning in context B (No Cue Ext-DCS). *p < 0.05 comparing reinstatement between context B groups; #p < 0.05 compared with the No Ext groups and groups marked with the # are not significantly different from each other. The number of subjects per group is listed within the gray bars (the effect of DCS was verified in a replicate group that is included in the overall analysis).

Experiment 2: determination of the brain loci mediating the systemic effect of DCS

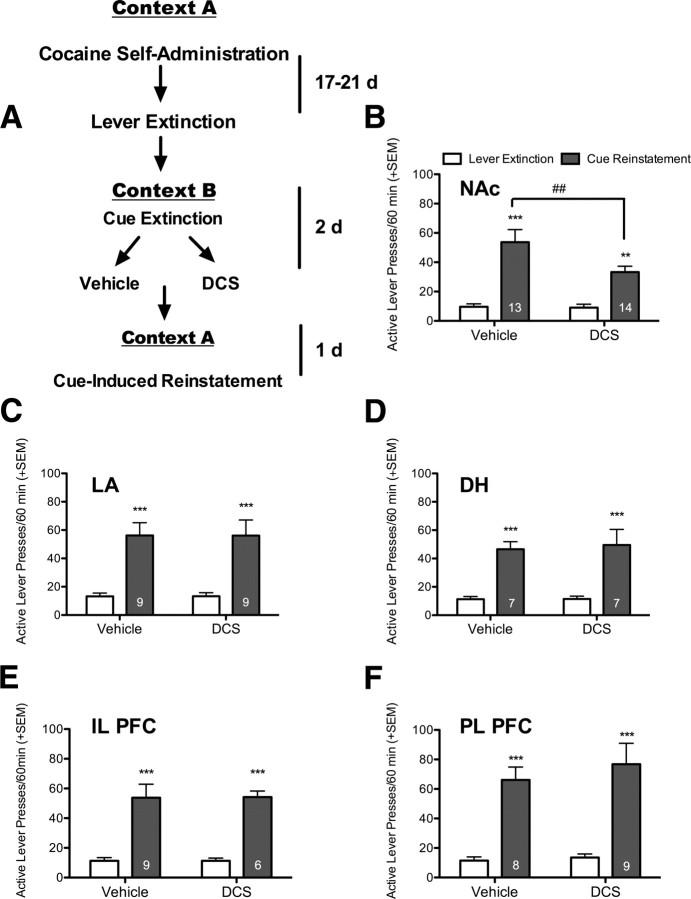

Experiment 2 was conducted to determine which brain region or regions are responsible for the ability of DCS to reduce the context dependency of cocaine-cue extinction. The LA, medial PFC subregions, and the NAc have all been implicated in extinction and/or reconsolidation of drug-associated stimuli (Miller and Marshall, 2005; Peters et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2009; Malvaez et al., 2010) and the hippocampus has been implicated in mediating the context specificity of fear extinction (Corcoran et al., 2005). Therefore, we examined the ability of DCS administered selectively into each of these brain regions to reduce the context specificity of cue extinction. Rats underwent cocaine self-administration and lever extinction as in experiment 1, and all groups were matched for performance such that there were no significant differences in number of infusions acquired across training or in the number of active lever presses on the last day of lever extinction.

Immediately following each Pavlovian cue extinction session in context B, rats received an infusion of vehicle or DCS into a specific brain region. The next day animals were tested for cue-induced reinstatement in context A. The results for each brain region were analyzed independently as these were all separate experiments conducted at different times. There was no significant effect of DCS treatment or interaction in the LA, IL PFC, PL PFC, or DH (p > 0.05 for all), while there was a significant effect of reinstatement for all of these regions (Fig. 3). This indicates that while there was a significant effect of the cues to reinstate lever pressing over extinction levels, DCS had no significant effect. On the other hand, in the NAc, there was a significant effect of test day (F(1,25) = 3.98, p < 0.001), and a significant interaction between treatment and test day (F(1,25) = 4.88, p = 0.037). Post hoc analysis revealed that the DCS-treated group showed significantly less cue-induced reinstatement than the vehicle group (p < 0.01), with no difference between groups in their prior responding during lever extinction (Fig. 3). There were no statistically significant differences between groups on inactive lever responding (data not shown). Therefore, it appears that DCS acting in the NAc, but not in the LA, IL or PL PFC, or DH, is capable of reducing the context specificity of extinction. The effect of DCS administered to each of these brain regions after Pavlovian extinction in context A was not assessed, as the goal of these studies was to determine which region is responsible for reducing the context specificity of extinction.

Figure 3.

DCS administration to the NAc produces a context-independent Pavlovian extinction of a cocaine-associated cue. A, Diagram representing the experimental paradigm. B, Cue-induced reinstatement in context A is significantly reduced in rats given intra-NAc injections of DCS after Pavlovian extinction sessions in context B. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 comparing reinstatement vs lever extinction, ##p < 0.01 comparing reinstatement between treatment groups. C–F, DCS administered directly into the LA (C), the DH (D), the IL PFC (E), and the PL PFC (F) had no effect on the context dependence of Pavlovian extinction. ***p < 0.001 comparing responding during lever extinction to cue-induced reinstatement responding. The results indicate that all treatment groups showed significant reinstatement that was not altered by DCS. The number of subjects per group is shown inside each of the gray bars (the NAc is a combination of 2 experiments, where the effects were found to be the same in each replicate).

Experiment 3: determination of the necessity of extinction learning for the intra-NAc DCS-induced reduction in cue-induced reinstatement

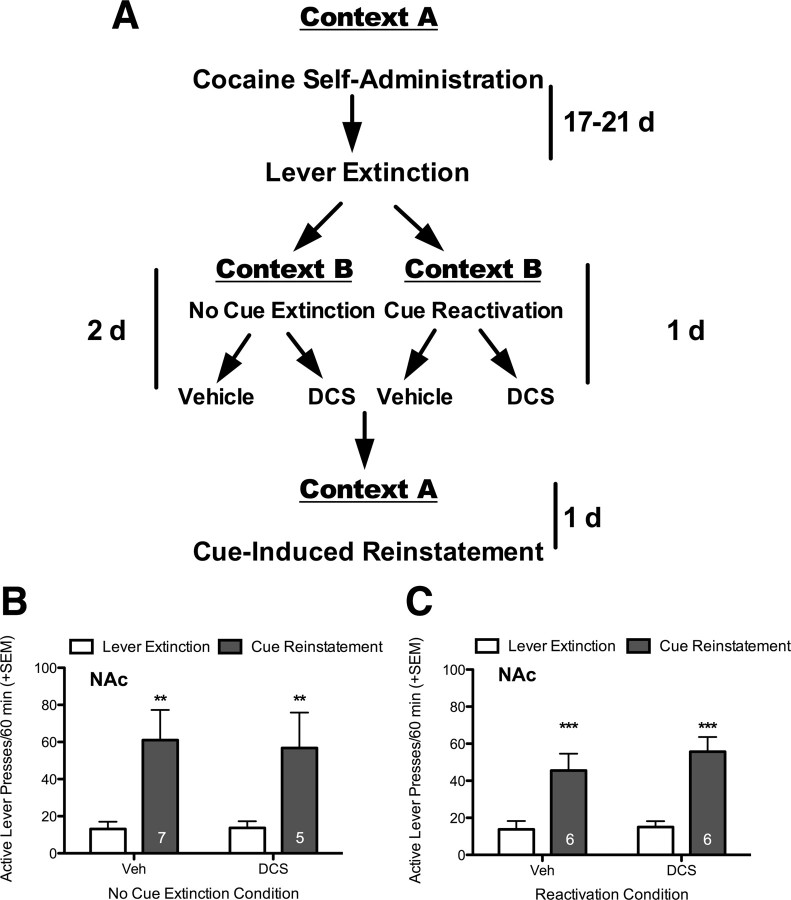

Finally, to determine whether the effect of DCS administered specifically in the NAc is dependent on a modulation of extinction learning, and is not due to general changes in glutamatergic signaling in the NAc, inhibition of reconsolidation, motoric, or motivational effects; two control experiments were performed. In the first, DCS was administered into the NAc immediately following each of 2 sessions, where the animals were placed in context B for 30 min without cue presentation (i.e., a no extinction control). On the following day, rats were tested for cue-induced reinstatement in context A, and while there was a significant effect of reinstatement (F(1,10) = 16.52, p = 0.002), there was no effect of treatment or interaction, indicating that DCS does not affect cue-induced reinstatement in the absence of extinction learning (Fig. 4B), as was shown in experiment 1 when DCS was given systemically. In the second experiment, we determined whether DCS administered to the NAc reduced reinstatement behavior because of an effect on memory reconsolidation. DCS or vehicle was infused into the NAc immediately following a single memory reactivation session in context B. The following day, cue-induced reinstatement was tested in context A. Again, there was a significant effect of test (F(1,10) = 45.74, p < 0.001), such that there was a significant cue-induced reinstatement of lever pressing, but there was no effect of treatment or interaction (Fig. 4C). There were no statistically significant differences between groups on inactive lever responding in either experiment (data not shown). Therefore, when given into the NAc, DCS has no apparent effect on memory reconsolidation, and this experiment provides further evidence that the effect of DCS was specific to cue extinction learning.

Figure 4.

Intra-NAc DCS does not alter cue-induced reinstatement when given in the absence of extinction training and does not affect cocaine-cue memory reconsolidation. A, Diagram representing the experimental paradigm. B, Rats were placed in context B for 2 d, but did not receive any extinction training. DCS given after these “No Cue Extinction” sessions had no effect on cue-induced reinstatement in context A. C, Rats had the cocaine-cue memory briefly reactivated by presenting the cue 3 times in context B. DCS given after this “Reactivation” session had no effect on cue-induced reinstatement in context A. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 when comparing responding during lever extinction to cue-induced reinstatement responding. All groups showed significant reinstatement, but no effect of DCS treatment. The number of subjects per group is shown inside each of the gray bars.

Histological analysis

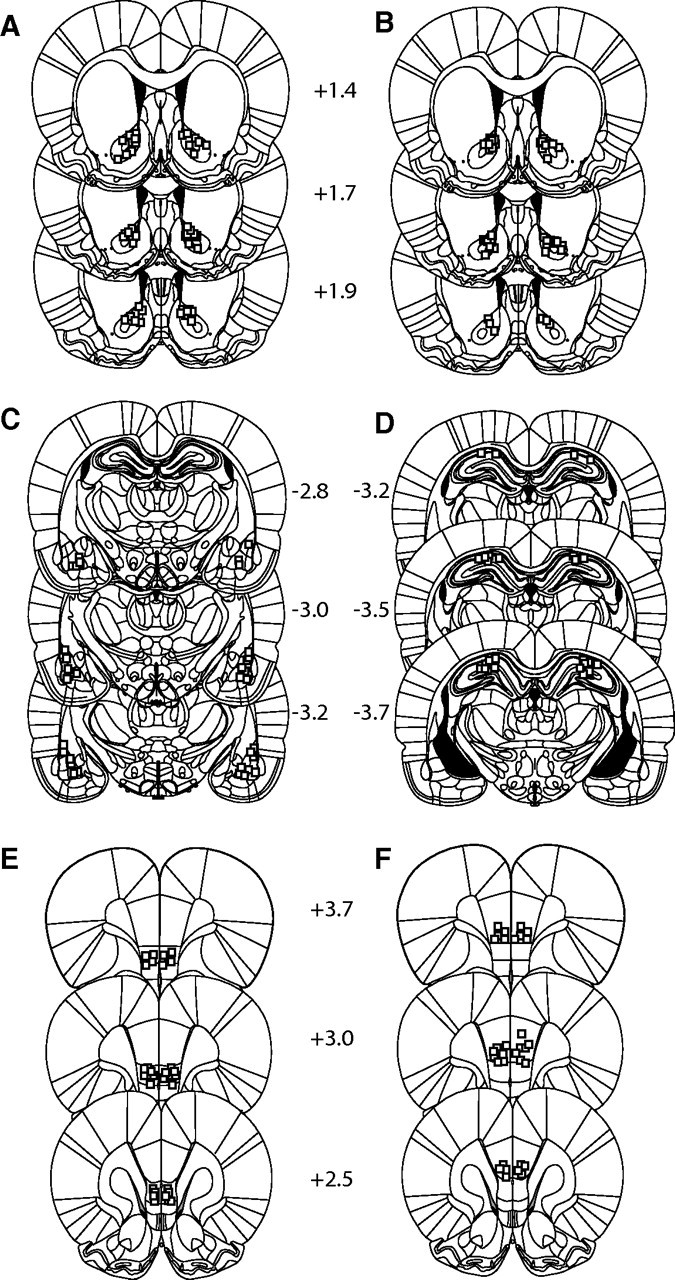

Figure 5 illustrates the intracranial injection sites for all of the experiments listed above. Animals with apparent infusions outside of the specified brain region were discarded from analysis.

Figure 5.

Histological representation of infusion sites for experiments 2 and 3. A, Approximate sites of infusions for individual rats in the NAc for experiment 2. B, NAc infusion sites for experiment 3. C, Basolateral and lateral amygdala. D, Dorsal hippocampus. E, Infralimbic prefrontal cortex. F, Prelimbic prefrontal cortex. Infusion sites are represented as open squares.

Discussion

The present results demonstrate that a Pavlovian cue extinction procedure can reduce cue-motivated behavior, but only when cue extinction is conducted in the same context as testing. Second, postextinction DCS in context B selectively attenuated cue-induced reinstatement in context A, indicating that a pharmacological manipulation can reduce the context dependence of cue extinction. Third, the systemic effect of DCS could be recapitulated by DCS administration into the NAc, but not into the LA, IL PFC, PL PFC, or DH. Finally, the ability of intra-NAc DCS to reduce cue-induced reinstatement was specific to cue extinction learning, and did not occur in the absence of extinction, or in a memory reactivation/reconsolidation paradigm.

The Pavlovian cue extinction procedure

To our knowledge, no previous study of cocaine cue-related behavior has determined whether Pavlovian cue extinction can reduce responding for that cue in a test of cue-induced reinstatement, as is shown here, because current models use forms of instrumental extinction. Pavlovian extinction is extinction that occurs in the absence of an instrumental response, and is how extinction of conditioned fear is conducted but is rarely assessed in the drug addiction field. Our findings provide evidence that an animal model of Pavlovian cue extinction is an effective method for reducing drug-cue motivated behavior. Our paradigm may be critical for neurobiological studies of reinstatement/extinction, as we believe it most closely mirrors human cue extinction, or exposure therapy, procedures relevant to addiction.

Testing the context specificity of extinction learning

In addition, we believe that it is essential to test whether manipulations that enhance extinction can do so in a context-independent manner, as this is highly likely to influence the success of any therapy. To date, only a few preclinical studies have attempted to determine whether behavioral manipulations can influence the context dependency of extinction for drug-associated stimuli. For example, Chaudhri et al. (2008) extinguished a discriminative stimulus associated with ethanol in a Pavlovian manner in multiple contexts and attenuated the renewal of ethanol port entries. Additionally, Kearns and Weiss (2007) attenuated renewal of cocaine seeking by associating a cocaine-associated discriminative stimulus with a food reinforcer (counterconditioning). However, no studies have found a pharmacological agent that can selectively reduce the context dependency of extinction for a drug cue as is shown here with DCS and also identify the brain region involved.

Nonetheless, many studies have demonstrated that DCS can enhance extinction learning when testing occurs in the same context (Walker et al., 2002; Ledgerwood et al., 2003; Botreau et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2006; Gabriele and Packard, 2007). Indeed, several studies have reported that DCS can facilitate extinction of instrumental responding for drugs and drug-associated contextual cues (Botreau et al., 2006; Paolone et al., 2009; Nic Dhonnchadha et al., 2010); however, no studies have shown that DCS can attenuate cue-induced reinstatement by a reduction in the context dependency of extinction in animal models. In fact, one study found that DCS does not alter the context dependency of extinction of a conditioned emotional fear response (Woods and Bouton, 2006). Therefore, the ability of DCS to reduce the context dependency of extinction observed here might be specific to cocaine-associated stimuli (but see Ressler et al., 2004).

Possible mechanism of action of DCS

DCS may reduce the context dependency of extinction through enhancement of extinction learning or through a disruption in the contextual encoding of extinction. However, if it was simply an enhancement of extinction learning we would have expected to see similar effects when DCS was infused in the LA/BLA and/or IL PFC as these regions are known to at least encode either retrieval or acquisition of extinction of instrumental responding for cocaine (Fuchs et al., 2006; Peters et al., 2008); and extinction of food-associated cues (McLaughlin and Floresco, 2007). However, we have only tested one dose of DCS in these brain regions, so it is possible that other doses would have been effective. The fact that the effect of systemic DCS was recapitulated by direct administration to the NAc indicates that both extinction learning and context encoding processes may be interacting because the NAc receives inputs from the BLA and PFC that might encode extinction learning, and from the DH, which might encode the contextual information (Groenewegen et al., 1999). However, the circuitry mediating Pavlovian extinction of drug-associated cues has not been determined so it may be that the NAc is critical for this form of extinction. Indeed, the NA shell has been shown to undergo important changes in glutamatergic plasticity after extinction learning that was specific to extinction of responding for cocaine and not sucrose (Sutton et al., 2003). While this study found effects in the shell and not core, we cannot presently say whether the effects of DCS we observed are core specific. It is possible that DCS-mediated actions at NMDA receptors during extinction learning alter glutamate receptor trafficking and/or glutamatergic tone in the accumbens that facilitates control over cocaine seeking. The generalization of extinction learning across contexts may require disruption of the interaction between circuits encoding extinction and contextual information, and further mechanistic studies should examine this possibility.

Other considerations

While DCS did reduce the context specificity of cue extinction, it is also important to note that no effect was observed in the absence of extinction, or during memory reactivation. These results indicate that extinction learning is necessary for the reported effect of DCS on reinstatement behavior, and that DCS does not have some nonspecific effect, such as a long-lasting reduction in locomotor activity. In addition, the ability of DCS to reduce the context specificity of extinction cannot be interpreted as a disruption of memory reconsolidation. We have previously shown that the memory reactivation paradigm used here is sufficient to induce reconsolidation of cocaine-cue memories in a manner that is dependent on protein kinase A (PKA) activity in the amygdala (Sanchez et al., 2010). Importantly, postmemory reactivation administration of DCS in the NAc did not affect cue-induced reinstatement, indicating that under these conditions DCS does not affect memory reconsolidation. Interestingly, using a similar self-administration protocol as described here, DCS administered to the BLA after 30 presentations of a cocaine-associated cue has been reported to increase later cue motivated behavior, indicating an enhancement of memory reconsolidation (Lee et al., 2009). The results of our study suggest that the ability of DCS to enhance reconsolidation of cocaine-cue memories may be specific to the BLA, as we did not observe any such effect in the NAc. It is important to note, however, that in the Lee et al. study DCS enhanced reconsolidation after 30 cue presentations, which might be considered a sufficient number to produce some extinction. Therefore, it may be critical to give a large number of cue presentations to initiate extinction learning. In our study, we never found that DCS enhanced cue-induced reinstatement when given after 120 cue presentations, indicating that there is not an enhancement in reconsolidation if sufficient cue presentations are given. However, in pilot studies where extinction training and testing occurred in context A, systemic DCS had no effect on cue-induced reinstatement when the cue was presented 60 or fewer times, potentially indicating competition between reconsolidation and extinction effects. Consequently, caution should be taken if DCS is administered as a treatment for addiction to ensure that sufficient extinction training has been given so as not to unintentionally actually increase the likelihood of relapse. Indeed, in a pilot clinical study, DCS administered before extinction therapy in cocaine addicts did not enhance extinction and may have stimulated craving (Price et al., 2009). It is possible that the number of cue presentations given in this study was not sufficient to induce extinction learning, and/or preextinction session DCS is not as effective as postsession administration, as was done in our experiments.

Relation of Pavlovian cue extinction to other procedures

In related studies of context-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking, instrumental extinction is conducted in an alternate context, and then lever responding is assessed in the original drug-taking context. Generally, the goal of these procedures is to isolate the role of context in motivating drug-seeking behavior (Crombag et al., 2008). To date critical brain regions and neurotransmitter systems involved in context-induced reinstatement have been identified, but these studies have yet to attempt enhancing extinction learning in the alternate context as we report here (e.g., Crombag et al., 2002; Bossert et al., 2004; Fuchs et al., 2005; Xie et al., 2010). Moreover, our Pavlovian extinction procedure is designed to isolate the role of discrete conditioned cues in controlling reinstatement of drug-seeking from other factors, such as the context, by extinguishing these other factors during the lever extinction phase of the experiment. We believe this targeted Pavlovian cue extinction paradigm is important for neurobehavioral studies of addiction, as it provides an animal model that more closely mirrors human cue extinction procedures, which are most often conducted in the absence of an instrumental response; particularly in imaging studies (Conklin and Tiffany, 2002). Human cue extinction also occurs in a context different from the drug-taking context, so it is critical to determine whether pharmacological manipulations aimed at enhancing extinction of drug-related cues can also reduce the context dependency of extinction.

Summary

Together, these data provide support for the hypothesis that the consolidation of cue extinction learning can be modified by adjunct pharmacotherapies such as DCS to reduce context specificity, and that the effect may critically depend on selective actions in the NAc that rely on experience dependent plasticity. Future studies should examine the persistence of Pavlovian cue extinction, identify the molecular mechanisms of cue extinction, and determine the efficacy of other agents that have been reported to enhance extinction learning.

Footnotes

This work was supported by US Public Health Service Grants DA022812 and DA0155222 and the Connecticut Mental Health Center.

References

- Bossert JM, Liu SY, Lu L, Shaham Y. A role of ventral tegmental area glutamate in contextual cue-induced relapse to heroin seeking. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10726–10730. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3207-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botreau F, Paolone G, Stewart J. D-Cycloserine facilitates extinction of a cocaine-induced conditioned place preference. Behav Brain Res. 2006;172:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learn Mem. 2004;11:485–494. doi: 10.1101/lm.78804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, King DA. Contextual control of the extinction of conditioned fear: tests for the associative value of the context. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1983;9:248–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhri N, Sahuque LL, Janak PH. Context-induced relapse of conditioned behavioral responding to ethanol cues in rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin CA, Tiffany ST. Applying extinction research and theory to cue-exposure addiction treatments. Addiction. 2002;97:155–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran KA, Desmond TJ, Frey KA, Maren S. Hippocampal inactivation disrupts the acquisition and contextual encoding of fear extinction. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8978–8987. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2246-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombag HS, Grimm JW, Shaham Y. Effect of dopamine receptor antagonists on renewal of cocaine seeking by reexposure to drug-associated contextual cues. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:1006–1015. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombag HS, Bossert JM, Koya E, Shaham Y. Context-induced relapse to drug seeking: a review. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:3233–3243. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Evans KA, Ledford CC, Parker MP, Case JM, Mehta RH, See RE. The role of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, basolateral amygdala, and dorsal hippocampus in contextual reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:296–309. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Feltenstein MW, See RE. The role of the basolateral amygdala in stimulus-reward memory and extinction memory consolidation and in subsequent conditioned cued reinstatement of cocaine seeking. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:2809–2813. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriele A, Packard MG. d-Cycloserine enhances memory consolidation of hippocampus-dependent latent extinction. Learn Mem. 2007;14:468–471. doi: 10.1101/lm.528007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewegen HJ, Wright CI, Beijer AV, Voorn P. Convergence and segregation of ventral striatal inputs and outputs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;877:49–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns DN, Weiss SJ. Contextual renewal of cocaine seeking in rats and its attenuation by the conditioned effects of an alternative reinforcer. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelamangalath L, Seymour CM, Wagner JJ. D-serine facilitates the effects of extinction to reduce cocaine-primed reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;92:544–551. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood L, Richardson R, Cranney J. Effects of d-cycloserine on extinction of conditioned freezing. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:341–349. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JL, Milton AL, Everitt BJ. Reconsolidation and extinction of conditioned fear: inhibition and potentiation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10051–10056. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2466-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JL, Gardner RJ, Butler VJ, Everitt BJ. D-cycloserine potentiates the reconsolidation of cocaine-associated memories. Learn Mem. 2009;16:82–85. doi: 10.1101/lm.1186609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malvaez M, Sanchis-Segura C, Vo D, Lattal KM, Wood MA. Modulation of chromatin modification facilitates extinction of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin RJ, Floresco SB. The role of different subregions of the basolateral amygdala in cue-induced reinstatement and extinction of food-seeking behavior. Neuroscience. 2007;146:1484–1494. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CA, Marshall JF. Molecular substrates for retrieval and reconsolidation of cocaine-associated contextual memory. Neuron. 2005;47:873–884. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nic Dhonnchadha BA, Szalay JJ, Achat-Mendes C, Platt DM, Otto MW, Spealman RD, Kantak KM. D-cycloserine deters reacquisition of cocaine self-administration by augmenting extinction learning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:357–367. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien CP, Childress AR, McLellan T, Ehrman R. Integrating systemic cue exposure with standard treatment in recovering drug dependent patients. Addict Behav. 1990;15:355–365. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90045-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolone G, Botreau F, Stewart J. The facilitative effects of d-cylcoserine on extinction of a cocaine-induced conditioned place preference can be long lasting and resistant to reinstatement. Psychopharmacology. 2009;202:403–409. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1280-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Ed 5. San Diego: Elsevier Academic; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Peters J, LaLumiere RT, Kalivas PW. Infralimbic prefrontal cortex is responsible for inhibiting cocaine seeking in extinguished rats. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6046–6053. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1045-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price KL, McRae-Clark AL, Saladin ME, Moran-Santa Maria MM, DeSantis SM, Back SE, Brady KT. D-Cycloserine and cocaine cue reactivity: preliminary findings. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35:434–438. doi: 10.3109/00952990903384332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressler KJ, Rothbaum BO, Tannenbaum L, Anderson P, Graap K, Zimand E, Hodges L, Davis M. Cognitive enhancers as adjuncts to psychotherapy: use of d-cycloserine in phobic individuals to facilitate extinction of fear. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1136–1144. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez H, Quinn JJ, Torregrossa MM, Taylor JR. Reconsolidation of a cocaine-associated stimulus requires amygdalar protein kinase A. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4401–4407. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3149-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Shalev U, Lu L, De Wit H, Stewart J. The reinstatement model of drug relapse: history, methodology and major findings. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:3–20. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MA, Schmidt EF, Choi KH, Schad CA, Whisler K, Simmons D, Karanian DA, Monteggia LM, Neve RL, Self DW. Extinction-induced upregulation in AMPA receptors reduces cocaine-seeking behaviour. Nature. 2003;421:70–75. doi: 10.1038/nature01249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JR, Olausson P, Quinn JJ, Torregrossa MM. Targeting extinction and reconsolidation mechanisms to combat the impact of drug cues on addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanos PK, Bermeo C, Wang GJ, Volkow ND. D-cycloserine accelerates the extinction of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference in C57BL/c mice. Behav Brain Res. 2009;199:345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torregrossa MM, Kalivas PW. Neurotensin in the ventral pallidum increases extracellular gamma-aminobutyric acid and differentially affects cue- and cocaine-primed reinstatement. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:556–566. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.130310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DL, Ressler KJ, Lu KT, Davis M. Facilitation of conditioned fear extinction by systemic administration or intra-amygdala infusions of d-cycloserine as assessed with fear-potentiated startle in rats. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2343–2351. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02343.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods AM, Bouton ME. D-cycloserine facilitates extinction but does not eliminate renewal of the conditioned emotional response. Behav Neurosci. 2006;120:1159–1162. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.5.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X, Ramirez DR, Lasseter HC, Fuchs RA. Effects of mGluR1 antagonism in the dorsal hippocampus on drug context-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2010;208:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1700-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]