Abstract

Objective:

It has been suggested that people who develop Parkinson disease (PD) may have a characteristic premorbid personality. We tested this hypothesis using a large historical cohort study with long follow-up.

Methods:

We conducted a historical cohort study in the region including the 120-mile radius centered in Rochester, MN. We recruited 7,216 subjects who completed the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) for research at the Mayo Clinic from 1962 through 1965 and we considered 5 MMPI scales to measure sensation seeking, hypomania, positive emotionality, social introversion, and constraint. A total of 6,822 subjects (94.5% of the baseline sample) were followed over 4 decades either actively (via interview and examination) or passively (via medical records).

Results:

During follow-up, 227 subjects developed parkinsonism (156 developed PD). The 3 MMPI scales that we selected to measure the extroverted personality construct (sensation seeking, hypomania, and positive emotionality) did not show the expected pattern of higher scores associated with reduced risk of PD. Similarly, the 2 MMPI scales that we selected to measure the introverted personality construct (social introversion and constraint) did not show the expected pattern of higher scores associated with increased risk of PD. However, higher scores for constraint were associated with an increased risk of all types of parkinsonism pooled together (hazard ratio 1.39; 95% CI 1.06–1.84; p = 0.02).

Conclusions:

We suggest that personality traits related to introversion and extroversion do not predict the risk of PD.

GLOSSARY

- CI

= confidence interval;

- HR

= hazard ratio;

- MMPI

= Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory;

- MSS

= MMPI Sensation Seeking Scale;

- PD

= Parkinson disease;

- PSY-5

= Personality Psychopathology Five Scales.

For nearly a century, there has been scientific debate about a distinctive premorbid personality in Parkinson disease (PD) characterized by decreased novelty seeking and increased moral rigidity, introversion, punctuality, cautiousness, and conventionality.1–6 These personality traits have been linked to the dopaminergic system by some authors7 and to the opioid and GABAergic systems by others.8,9 Because the hypothesis of a personality at risk for PD remains controversial,9–12 we tested the hypothesis using a large historical cohort study with long-term follow-up.13–15

METHODS

Study sample.

The Mayo Clinic Cohort Study of Personality and Aging is a geographically defined subset of a previously established Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) cohort, as described extensively elsewhere.13,16 In brief, approximately 50,000 Mayo Clinic outpatients completed the MMPI for research purposes (not because of clinical indication) from 1962 through 1965. The study included ambulatory patients who came to the Mayo Clinic from anywhere in the United States for medical reasons other than an acute illness, a psychiatric disorder, a surgical procedure, or hospitalization. At that time, an effort was made to recruit all eligible patients in a consecutive manner, and the participation rate was 95%.16

We restricted the established cohort to 7,216 subjects who resided at the time of MMPI completion in 1 of 72 counties located approximately within a 120-mile radius centered in Rochester, MN, as described elsewhere.13 This geographic restriction increased the likelihood that cohort members had used the Mayo Clinic as a primary source of medical care following completion of the baseline MMPI (contributing to passive follow-up). The geographic restrictions also increased the feasibility of the study by reducing the cost and travel time for the in-person examinations.13,14

Personality measures.

The MMPI includes 550 different statements concerning thoughts, feelings, attitudes, physical and emotional symptoms, and life experiences. The instrument is self-administered and the subject is asked to respond “true” or “false” to each statement.17 The MMPI was originally intended to be used by physicians (primarily internists) to detect psychological symptoms in their medical practice.18 However, MMPI data also provide a standardized and quantitative measure of personality functioning.17

We selected 5 MMPI scales measuring sensation seeking, hypomania, positive emotionality, social introversion, and constraint.19–22 The 3 scales of sensation seeking, hypomania, and positive emotionality were selected to measure the construct of extroverted personality. By contrast, the 2 scales of social introversion and constraint were selected to measure the construct of introverted personality (figure e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at www.neurology.org).

As a measure of novelty seeking personality, we used the MMPI Sensation Seeking Scale (MSS) described by Viken and colleagues22 (18 items with equal weight). Subjects with high scores are described as seeking varied, novel, complex, and intense sensations and experiences, and willing to take physical, social, and financial risks for the sake of such experience. This definition followed the theoretical concept of sensation seeking developed by Zuckerman.23

Subjects with high scores on the hypomania scale (MMPI Scale 9 [Ma, Hypomania]; 46 items with equal weight) are described as sociable, talkative, individualistic, impulsive, enthusiastic, curious, adventurous, and prone to alcohol consumption.19 As a measure of impulsivity, we used the Positive Emotionality/Extroversion Scale from the original version of the Personality Psychopathology Five Scales (PSY-5; 34 items with equal weight).20,21 Subjects with high scores on this scale are described as disposed to experience positive affects, to seek and enjoy social experiences, and to have the energy to pursue goals and engage in life's tasks.

Subjects with high scores on the social introversion scale (MMPI Scale 0 [Si, Social Introversion-Extroversion]; 70 items with equal weight) are described as having manifest social introversion and a lack of desire to be with others, whereas subjects with low scores are described as having a tendency to be extroverted, to enjoy social interactions, and to actively seek such contacts.19 Finally, we used the Constraint Scale from the original version of the PSY-5 scales that combines features of control vs impulsiveness, harm avoidance, and traditionalism (29 items with equal weight).20,21 High scores reflect a perfectionist approach to problem-solving, a conventional, conforming, and controlled demeanor, with personal relationships characterized by social distance and formality, and relatively rigid ties to traditional standards.24

Follow-up procedures.

All subjects were assessed by research team members who were kept uninformed of the results of the baseline MMPI using 1 active and 2 passive surveillance methods. The active method was a 2-phase survey including individual screening of the subjects for parkinsonism via telephone and subsequent examination of those who screened positive (1 screening contact for each subject staggered over 2001– 2006).25,26 To find the address of persons who moved since their last contact with the medical records-linkage system or with the Mayo Clinic, we used a combination of Web-based tracking tools and obituaries published in local newspapers and archived at state historical societies.15

The telephone interview was done by 1 of 6 trained research assistants and was completed directly with the subject whenever possible; for deceased or otherwise incapacitated subjects (e.g., deaf, cognitively impaired, or terminally ill), we contacted a proxy informant. We initially identified contact persons from medical records or from other sources and asked them to judge who would be the most knowledgeable proxy. The best proxy was then invited to serve as the informant.

The verbatim text of the instruments used for direct or proxy screening has been reported elsewhere.25 Subjects screened positive if they had a previous diagnosis of PD or parkinsonism, previous treatment with levodopa, at least 2 of 9 symptoms of parkinsonism, or shaking without other symptoms.25 We validated the screening instruments in 3 separate samples, and we observed sensitivity values of 97.3%, 88.0%, and 89.1% and specificity values of 43.8%, 63.8%, and 69.5%.25,26

Subjects who were alive and screened positive were offered an examination by a movement disorders specialist either at the Mayo Clinic or at their home if they resided within a 5-state region including Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, and North and South Dakota. If they resided outside of the 5-state region, they were examined only if they were willing to travel to the Mayo Clinic (with reimbursement of travel expenses). In addition, we obtained copies of medical records from care providers located anywhere in the United States for subjects who screened positive but could not be examined or were deceased.

Independent of the contact described above, subjects who resided in Olmsted County, MN, were also followed passively through review of inpatient and outpatient medical records in the medical records-linkage system of the Rochester Epidemiology Project.27 Similarly, subjects who resided outside of Olmsted County were followed passively by searching the Mayo Clinic records archive. Both the medical records-linkage system and the Mayo Clinic records archive maintain electronic indices of diagnostic codes (based on the International Classification of Diseases) that were searched for 53 specific codes related to parkinsonism.28 The medical records of subjects with diagnostic codes of interest were abstracted manually by a specifically trained nurse and were adjudicated by a neurologist (J.H.B.) to confirm the diagnosis of parkinsonism or PD, as described elsewhere.28 As a second passive surveillance method, we obtained death certificates as described elsewhere.14 We considered all causes of death to ascertain parkinsonism (underlying, intermediate, immediate, and other significant conditions).

Diagnostic criteria.

For subjects who were examined or had adequate medical record information, we used a set of previously published diagnostic criteria for parkinsonism and PD.28 Parkinsonism included PD, drug-induced parkinsonism, parkinsonism in dementia, parkinsonism unspecified, and other parkinsonism (including vascular parkinsonism, progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system atrophy, corticobasal ganglionic degeneration, and other rare disorders).28 For subjects who could not be examined and had insufficient information in their medical records, parkinsonism or PD were defined as a previous diagnosis reported by the subject or by the proxy at interview, or listed on the death certificate. However, subjects who screened positive for parkinsonism but did not report a diagnosis of parkinsonism or PD were considered unaffected.

Statistical analysis.

For all study subjects, we computed the follow-up time between the date of MMPI completion and one of the following endpoints, whichever came first: onset of parkinsonism (including PD), death, interview for the study, or time of last medical record entry. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models with age as the time scale to allow for complete age adjustment and including sex (whenever appropriate). The assumption of proportional hazards was assessed by graphical methods and by introducing a time-dependent coefficient in the Cox models.

We partitioned the sample at baseline into quartiles of the distribution of scores for each of the 5 MMPI scales, and used the lower 3 quartiles (quartiles 1 through 3) as reference. The quartiles were defined using sex-specific and age-specific distributions (by decades of age at time of MMPI completion).13 Analyses were conducted overall, separately for men and women, and for 3 broad strata of age at time of MMPI completion (20–39, 40–49, and 50–69 years).

We also conducted separate analyses adjusted for scores on the MMPI smoking proneness scale (quartile 4 vs quartiles 1 through 3) as a surrogate for smoking (information not available), and analyses adjusted for the smoking proneness scale as well as for alcohol use and self-assessed general health (2 specific MMPI questions).14,29 In addition, we conducted a set of secondary analyses adjusted for education as a marker of socioeconomic status (<9; 9–12; 13–16; >16 years of education) and for type of interview (direct vs proxy). These analyses were considered secondary because they were restricted to the 4,261 cohort members who provided education information via interview. Finally, we performed analyses restricting the definition of outcome to subjects with a diagnosis of PD confirmed by in-person examination or by medical record review. All analyses were completed using SAS® (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and tests of statistical significance were conducted at the 2-tailed α level of 0.05.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consent.

All study procedures and ethical aspects were approved by the institutional review boards of the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center. In addition, written informed consent was obtained from all subjects who were examined as part of the study.

RESULTS

Study sample.

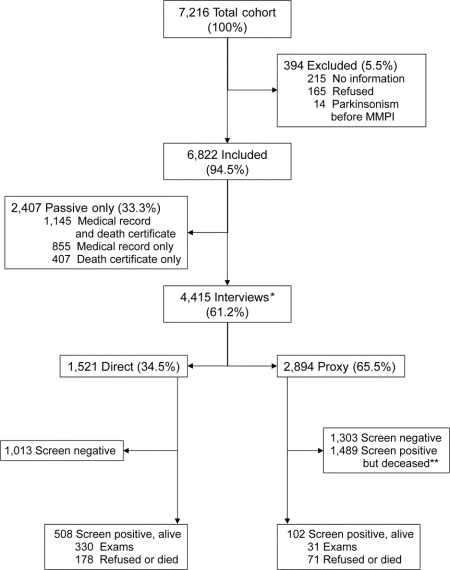

Figure 1 shows a detailed flow chart of the study. Of 7,216 subjects eligible for our study, 394 subjects (5.5%) had no information after the MMPI was completed, refused participation, or had parkinsonism at baseline. The remaining 6,822 subjects (94.5%) were included in our analyses. A total of 5,816 subjects (85.3%) had complete follow-up because they met at least 1 of 3 criteria: 1) reached the outcome of parkinsonism or PD; 2) were interviewed directly or via proxy; or 3) had a medical contact with the medical records-linkage system or with the Mayo Clinic records archive within 3 years preceding death or the time of the study (midpoint, December 31, 2003). The remaining 1,006 subjects (14.7%) were followed for a number of years through the medical records-linkage system or the Mayo Clinic records database and were censored at the time of last contact. The median age at the time of MMPI completion for the overall cohort of 6,822 subjects was 48.3 years (range, 20–69 years, by design), and the median length of follow-up was 29.2 years (range, <1–44.8 years).

Figure 1 Flow chart of study cohort

*Of these 4,415 subjects, 4,309 (97.6%) resided within and 106 (2.4%) resided outside of the 5-state region at the time of the follow-up interview. Of the 106 subjects who resided outside of the 5-state region, 33 screened positive for parkinsonism, 32 of them were alive, and 7 were examined. **Of these 1,489 subjects, 1,211 (81.3%) had both medical record and death certificate information, 34 (2.3%) only medical record information, 231 (15.5%) only death certificate information, and the remaining 13 (0.9%) had neither. MMPI = Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory.

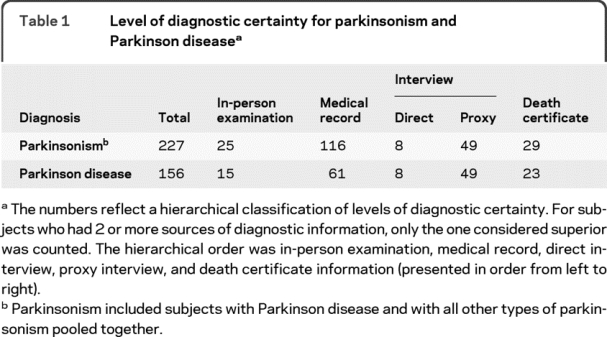

Of the 1,521 subjects who were alive and were screened directly, 508 screened positive for parkinsonism (33.4%), and 330 of them were examined in person (65.0%). Of the 2,894 subjects who were screened via proxy, 1,591 screened positive (55.0%), 102 of them were alive, and 31 of those alive were examined in person (30.4%; alive but incapacitated). Table 1 shows the level of diagnostic certainty for parkinsonism (227 patients) and PD (156 patients). The number of subjects with PD diagnosed via in-person examination or medical record review was similar to the number expected using published age- and sex-specific incidence rates from Olmsted County, MN (standardized incidence ratio 0.94; 95% CI 0.74–1.18; p = 0.62).15,28

Table 1 Level of diagnostic certainty for parkinsonism and Parkinson disease

Extroversion and risk of PD.

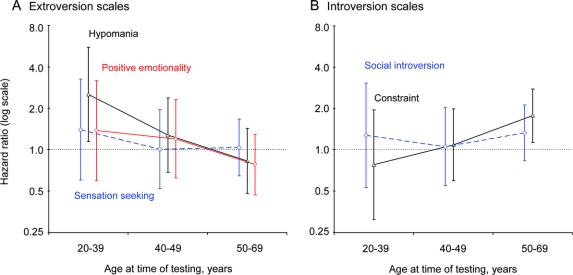

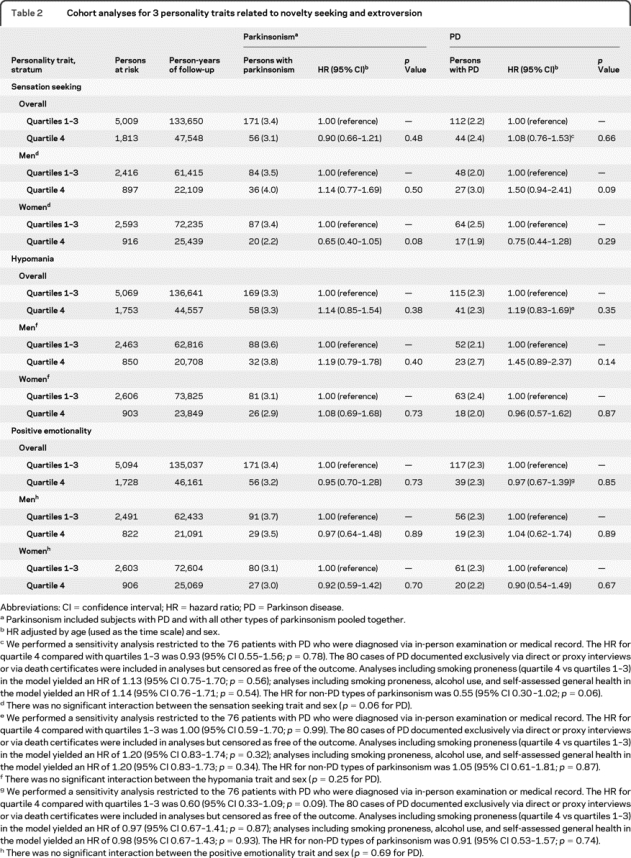

Table 2 shows our cohort analyses for the 3 MMPI scales related to extroversion. No significant associations were found for any of the 3 scales for PD alone or for PD combined with other types of parkinsonism. The results were similar for men and women, and across the 3 broad strata by age at time of MMPI completion for the sensation seeking and positive emotionality scales; however, there was an age at time of testing effect for the hypomania scale (figure 2 and table e-1). The results were also similar in secondary analyses adjusted for smoking proneness alone or for smoking proneness, alcohol use, and self-reported general health (table 2, footnotes). The results were similar in analyses adjusted for education and type of interview (data not shown). Finally, the results were similar in sensitivity analyses using a more stringent definition of PD and in analyses for non-PD types of parkinsonism (table 2, footnotes).

Table 2 Cohort analyses for 3 personality traits related to novelty seeking and extroversion

Figure 2 Hazard ratios (HRs) for Parkinson disease for 5 Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) personality scales stratified by age at time of MMPI completion

(A) The 3 scales measuring the extroverted personality construct yielded higher HRs when measured earlier in life. However, only the trend for the hypomania scale was significant. (B) By contrast, the 2 scales measuring the introverted personality construct yielded higher HRs when measured later in life. However, the trends were not significant. HRs and 95% confidence interval bars were staggered to improve the graphic display.

Introversion and risk of PD.

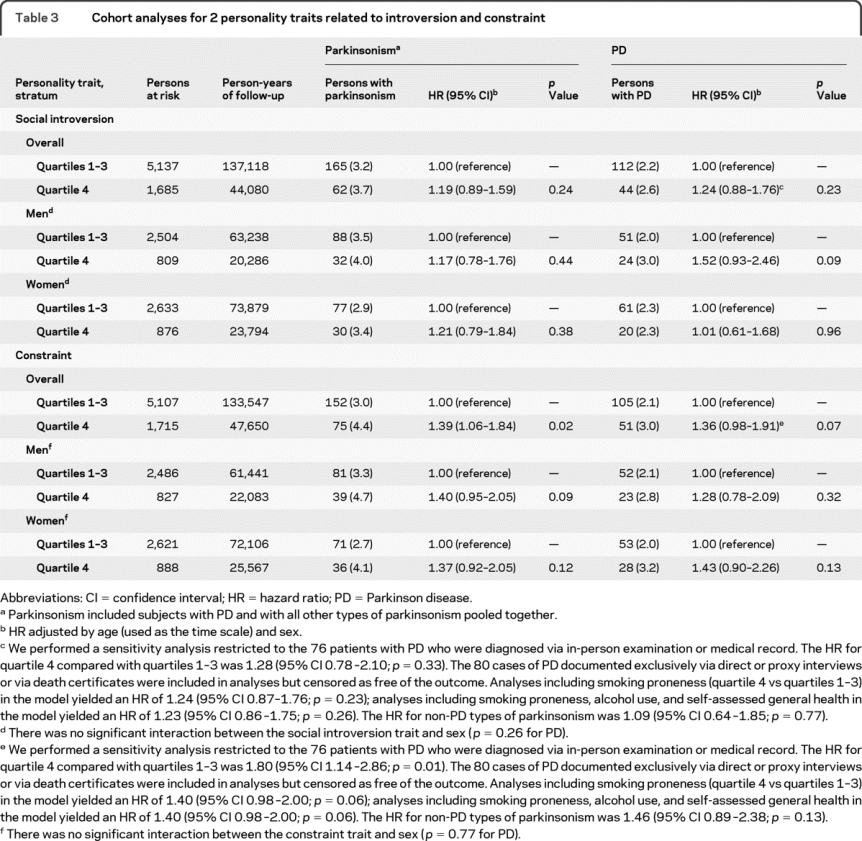

Table 3 shows our cohort analyses for the 2 MMPI scales related to introversion and constraint. No significant associations were found for PD alone. However, higher scores for constraint were associated with an increased risk of PD combined with other types of parkinsonism (HR 1.39; 95% CI 1.06–1.84; p = 0.02). The HR was similarly increased for PD; however, it did not reach significance. The findings were similar in men and women and across the 3 broad strata by age at time of MMPI completion (figure 2 and table e-1). The results were also similar in secondary analyses adjusted for smoking proneness alone or for smoking proneness, alcohol use, and self-reported general health (table 3, footnotes). The results were similar in analyses adjusted for education and type of interview (data not shown). Finally, the results were similar using a more stringent definition of PD and in analyses for non-PD types of parkinsonism (table 3, footnotes).

Table 3 Cohort analyses for 2 personality traits related to introversion and constraint

DISCUSSION

Analyses for the 3 MMPI scales that we selected to measure the construct of extroversion (sensation seeking, hypomania, and positive emotionality) did not show the expected pattern of higher scores associated with reduced risk of PD. Similarly, analyses for the 2 MMPI scales that we selected to measure the construct of introversion (social introversion and constraint) did not show the expected pattern of higher scores associated with increased risk of PD. The isolated finding of higher risk of PD combined with other types of parkinsonism in subjects with high scores for constraint remains of uncertain interpretation and may be due to chance (type 1 error). Considering the overall results of the 5 MMPI scales together, we suggest that the extroversion–introversion personality construct as measured by the MMPI is not predictive of the long-term risk of PD.

Our findings are consistent with studies that did not show an overall association between PD and personality traits related to introversion and extroversion preceding the onset of motor symptoms.11,12 However, our findings are in contrast with some case-control studies that showed an association.2,5,6 These case-control studies may be limited because of a possible cause-effect inversion, whereby the personality traits observed may have been consequences (or early manifestations) of PD rather than risk factors. In addition, these case-control studies may have been affected by recall bias and by the lack of adequate instruments to measure personality traits from early in life.

The lack of overall associations in our study may be due to the heterogeneity of subjects with a given personality trait, to the heterogeneity of subjects with PD, or to a combination of both types of heterogeneity. In addition, it is possible that there is an association between the extroversion-introversion personality construct and PD; however, the association is highly dependent on the age window in which personality is measured. Our study provides only suggestive evidence for this alternative hypothesis (figure 2).

Our study has a number of strengths. First, it is a relatively large, historical cohort study using a well-defined and standard battery of 550 questions measuring personality. This design reduced recall bias and the confounding effect of personality changes that may follow the onset of parkinsonism. Because the MMPI was completed as part of a research project and not because of a medical indication, the confounding effect of preexisting medical conditions was also reduced.

Second, the MMPI is a familiar tool for clinicians and researchers, and the specific scales used in this study have been previously validated. In particular, the MSS has been recently developed and compared with Zuckerman's Sensation Seeking Scale.22,30

Third, because we restricted the cohort to subjects living within a 120-mile radius of Rochester, MN, we used the medical records-linkage system of the Rochester Epidemiology Project and the Mayo Clinic records archive to perform a passive follow-up. The use of both passive and active methods to follow our cohort members allowed for a more complete case ascertainment than using either method alone. Thus, our capture rate for incident cases of PD was comparable with published incidence rates using similar methods.28

Fourth, the long-term follow-up (median, 29.2 years), the large sample size, and the diverse age and sex composition permitted the stratification of our sample into 2 subcohorts of approximately equal size for men and women, and into 3 broad age subcohorts.

Our study also has limitations. First, the sample was not recruited from a well-defined population through randomization.13 On the other hand, efforts were made to recruit patients sequentially, and the participation rate at baseline was 95%. In addition, the age and sex patterns of scores found in our sample at baseline were similar to those observed in a population-based random sample.13 Second, the diagnosis of PD was confirmed by in-person examination or by medical record review for only 48.7% of the patients. However, sensitivity analyses including only patients with more definite diagnoses of PD yielded similar results. Finally, we cannot exclude that introverted subjects were more reluctant to participate in an in-person examination than extroverted subjects, and were thus less likely to be diagnosed with PD. However, our use of passive follow-up methods should have reduced this possible limitation.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Statistical analysis was conducted by B.R. Grossardt.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Barbara J. Balgaard for typing the manuscript.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Arabia and B.R. Grossardt report no disclosures. Dr. Colligan receives research support from the NIH (MH076111 [Co-I]) and the DHHS/FDA (HHSF10037C [Co-I]). Dr. Bower has served as a consultant to Allergan, Inc. and receives research support from the NIH (1R21TW008412-01 [PI]). Dr. Maraganore may accrue revenue from pending patent applications related to the prediction of Parkinson disease and the treatment of neurodegenerative disease; has received license fee payments and royalty payments from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals (Method to treat Parkinson's disease); and receives research support from the NIH (ES010751 [PI]). Dr. Ahlskog serves on the editorial boards of Parkinsonism and Related Disorders and Clinical Neuropharmacology; receives royalties from publishing The Parkinson's Disease Treatment Book (Oxford University Press, 2005) and Parkinson's Disease Treatment Guide for Physicians (Oxford University Press, 2009), Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders (Humana Press, 2000), and Surgical Treatment of Parkinson's Disease and Other Movement Disorders (Humana Press, 2003); and receives research support from the NIH (NS040256-R [Co-I]). Dr. Geda receives research support from the NIH (K01 MH68351 [PI]; AG06786 [Co-I]), Mayo CTSA (RR024150 [Career Transition Award]), the RWJ Foundation (Harold Amos Scholar), and the Robert H. and Clarice Smith and Abigail Van Buren Alzheimer's Disease Research Program. Dr. Rocca receives research support from the NIH (AR030582 [PI], AG006786 [Co-I], and ES010751 [Co-I]).

Supplementary Material

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. W.A. Rocca, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Health Sciences Research, and Department of Neurology, College of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905 rocca@mayo.edu

Supplemental data at www.neurology.org

Study funding: Supported by the NIH (R01 NS033978) and by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (R01 AR030582).

Disclosure: Author disclosures are provided at the end of the article.

Received December 29, 2009. Accepted in final form April 9, 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eatough VM, Kempster PA, Stern GM, Lees AJ. Premorbid personality and idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Adv Neurol 1990;53:335–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poewe W, Karamat E, Kemmler GW, Gerstenbrand F. The premorbid personality of patients with Parkinson's disease: a comparative study with healthy controls and patients with essential tremor. Adv Neurol 1990;53:339–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menza MA, Golbe LI, Cody RA, Forman NE. Dopamine-related personality traits in Parkinson's disease. Neurology 1993;43:505–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menza M. The personality associated with Parkinson's disease. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2000;2:421–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menza MA, Forman NE, Goldstein HS, Golbe LI. Parkinson's disease, personality, and dopamine. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1990;2:282–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hubble JP, Cao T, Hassanein RE, Neuberger JS, Koller WC. Risk factors for Parkinson's disease. Neurology 1993;43:1693–1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cloninger CR. A systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants: a proposal. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987;44:573–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bardo MT, Donohew RL, Harrington NG. Psychobiology of novelty seeking and drug seeking behavior. Behav Brain Res 1996;77:23–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaasinen V, Nurmi E, Bergman J, et al. Personality traits and brain dopaminergic function in Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:13272–13277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishihara L, Brayne C. What is the evidence for a premorbid parkinsonian personality: a systematic review. Mov Disord 2006;21:1066–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glosser G, Clark C, Freundlich B, Kliner-Krenzel L, Flaherty P, Stern M. A controlled investigation of current and premorbid personality: characteristics of Parkinson's disease patients. Mov Disord 1995;10:201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs H, Heberlein I, Vieregge A, Vieregge P. Personality traits in young patients with Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand 2001;103:82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rocca WA, Grossardt BR, Peterson BJ, et al. The Mayo Clinic Cohort Study of Personality and Aging: design and sampling, reliability and validity of instruments, and baseline description. Neuroepidemiology 2006;26:119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grossardt BR, Bower JH, Geda YE, Colligan RC, Rocca WA. Pessimistic, anxious, and depressive personality traits predict all-cause mortality: the Mayo Clinic Cohort Study of Personality and Aging. Psychosom Med 2009;71:491–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bower JH, Grossardt BR, Maraganore DM, et al. Anxious personality predicts an increased risk of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord (in press 2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Swenson WM, Pearson JS, Osborne D. An MMPI Source Book: Basic Item, Scale, and Pattern Data on 50,000 Medical Patients. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hathaway SR, McKinley JC. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, rev. ed. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press; 1943. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKinley JC, Hathaway SR. The identification and measurement of the psychoneuroses in medical practice: The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. JAMA 1943;122:161–167. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dahlstrom WG, Welsh GS, Dahlstrom LE. An MMPI Handbook, rev. ed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harkness AR, McNulty JL, Ben-Porath YS. The Personality Psychopathology Five (PSY-5): constructs and MMPI-2 scales. Psychol Assess 1995;7:104–114. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harkness AR, McNulty JL. The Personality Psychopathology Five (PSY-5): issue from the pages of a diagnostic manual instead of a dictionary. In: Strack S, Lorr M, eds. Differentiating Normal and Abnormal Personality. New York: Springer; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viken RJ, Kline MP, Rose RJ. Development and validation of an MMPI-based Sensation Seeking Scale. Pers Individ Dif 2005;38:619–625. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuckerman M. Behavioral Expressions and Biosocial Bases of Sensation Seeking. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watson D, Clark LA. Behavioral disinhibition versus constraint: a dispositional perspective. In: Wegner DM, Pennebaker JW, eds. Handbook of Mental Control. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rocca WA, Maraganore DM, McDonnell SK, Schaid DJ. Validation of a telephone questionnaire for Parkinson's disease. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:517–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rocca WA, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, et al. Increased risk of parkinsonism in women who underwent oophorectomy before menopause. Neurology 2008;70:200–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melton LJ 3rd. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc 1996;71:266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bower JH, Maraganore DM, McDonnell SK, Rocca WA. Incidence and distribution of parkinsonism in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976–1990. Neurology 1999;52:1214–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipkus IM, Barefoot JC, Feaganes J, Williams RB, Siegler IC. A short MMPI scale to identify people likely to begin smoking. J Pers Assess 1994;62:213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zuckerman M. Sensation Seeking: Beyond the Optimal Level of Arousal. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1979. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.