Abstract

In many fungal pathogens, infection is initiated by conidial germination. Subsequent stages involve germ tube elongation, conidiation, and vegetative hyphal fusion (anastomosis). Here, we used live-cell fluorescence to study the dynamics of green fluorescent protein (GFP)- and cherry fluorescent protein (ChFP)-labeled nuclei in the plant pathogen Fusarium oxysporum. Hyphae of F. oxysporum have uninucleated cells and exhibit an acropetal nuclear pedigree, where only the nucleus in the apical compartment is mitotically active. In contrast, conidiation follows a basopetal pattern, whereby mononucleated microconidia are generated by repeated mitotic cycles of the subapical nucleus in the phialide, followed by septation and cell abscission. Vegetative hyphal fusion is preceded by directed growth of the fusion hypha toward the receptor hypha and followed by a series of postfusion nuclear events, including mitosis of the apical nucleus of the fusion hypha, migration of a daughter nucleus into the receptor hypha, and degradation of the resident nucleus. These previously unreported patterns of nuclear dynamics in F. oxysporum could be intimately related to its pathogenic lifestyle.

Fusarium oxysporum is a soilborne pathogen that causes substantial losses in a wide variety of crops (12) and has been reported as an emerging human pathogen (36, 38). Similar to other fungal pathogens (18), the early stages of interaction between F. oxysporum and the host are crucial for the outcome of infection (11). Key processes occurring during these initial stages include spore germination, adhesion to the host surface, establishment of hyphal networks through vegetative hyphal fusion, differentiation of infection hyphae, and penetration of the host (53). Surprisingly, very little is known about the cytology of basic processes, such as spore germination and hyphal development, which play key roles during infection by F. oxysporum.

F. oxysporum produces three types of asexual spores: microconidia, macroconidia, and chlamydospores (9, 26). Germination usually represents the first step in the colonization of a new environment, including the host. Once dormancy is broken, spores undergo a defined set of morphogenetic changes that lead to the establishment of a polarized growth axis and the emergence of one or multiple germ tubes (reviewed by d'Enfert and Hardham [10, 19]). In certain fungi, such as Aspergillus nidulans, germ tube emergence and septum formation are subject to precise spatial controls and are tightly coordinated with nuclear division (20, 22, 34, 42, 54). In contrast, in spores from other filamentous fungi, such as macroconidia of Fusarium graminearum, nuclear division is not required for the emergence of germ tubes (21, 48). During hyphal growth, multinucleate fungi display distinct mitotic patterns, such as asynchronous nuclear division in Neurospora crassa and Ashbya gossypii (15, 16, 29, 30, 33, 49), parasynchronous in A. nidulans (7, 15, 23, 46), and synchronous in Ceratocystis fagacearum (1, 15).

Vegetative hyphal fusion, or anastomosis, is a common developmental process during the life cycle of filamentous fungi that is thought to serve important functions in intrahyphal communication, nutrient transport, and colony homeostasis (41). F. oxysporum undergoes anastomosis (8, 25, 32, 40), and although this process is not strictly required for plant infection, it appears to contribute to efficient colonization of the root surface (39).

The aim of this study was to explore nuclear dynamics during different developmental stages of F. oxysporum that are of key relevance during the establishment of infection. They include germination of microconidia, vegetative hyphal development, and conidiation, as well as vegetative hyphal fusion during colony establishment. Fusion PCR-mediated gene targeting (55) was used to C-terminally label histone H1 in F. oxysporum (FoH1) with either green fluorescent protein (GFP) or the cherry variant (ChFP), allowing us to perform, for the first time, live-cell analysis of nuclear dynamics in this species. Our study revealed distinct patterns of nuclear divisions in F. oxysporum. Moreover, we report, for the first time in an ascomycete, that hyphal fusion initiates a series of nuclear events, including mitosis in the fusing hypha and nuclear migration into the receptor hypha, followed by degradation of the resident nucleus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal isolates and culture conditions.

F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici race 2 wild-type strain 4287 (FGSC 9935) was used in all experiments. For microconidium production, cultures were grown in potato dextrose broth (PDB) (Difco, Detroit, MI) at 28°C with shaking at 170 rpm for 3 days (11). For microscopy analyses, microconidia were inoculated on PDB diluted 1:50 in 20 mM glutamic acid with or without 0.8% (wt/vol) agarose.

Construction of GFP- and ChFP-tagged constructs and fungal transformation.

The histone H1 gene (foH1) was identified as locus FOXG_12732 in the F. oxysporum genome sequence (https://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/). C-terminal GFP tagging of the foH1 gene was accomplished by a modified version of the fusion PCR gene-targeting method described previously (55), using a cassette containing a hinge region encoding five Gly-plus-Ala repeats (GA) in frame at the N terminus of GFP (55), followed by the hygromycin resistance (Hygr) cassette as a selectable marker (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). Three fragments were first amplified. The first fragment, the GA-GFP-Hygr cassette, was amplified using primers HIST1-ADP and HIST1-HYG (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). For the second fragment, a 1,930-bp region located 9 bp upstream of the foH1 gene stop codon was amplified using primers HIST1-1 and HIST1-2 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). For the third fragment, a 2,100-bp region located 43 bp downstream of the foH1 gene stop codon was amplified using primers HIST1-3 and HIST1-4 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Each amplification reaction was performed using the Expand High Fidelity PCR System (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) following the manufacturer's recommendations. The amplified fragments were cleaned with the Geneclean Turbo Nucleic Acid Purification kit and quantified using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. A first fusion PCR was performed in a 25-μl final volume containing 100 ng of each amplified genomic fragment, 300 ng of GA-GFP-Hygr cassette, 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1× Expand High Fidelity buffer, and 1.3 U of Expand High Fidelity enzyme mix. No primers were added to this reaction mixture. The PCR cycling conditions were 94°C for 5 min and then 35 cycles of 94°C for 45 s, 60°C for 2 min, and 68°C for 6 min, followed by a final extension at 68°C for 10 min. A second fusion PCR was performed using 2 μl of the first fusion PCR product as a template, 0.2 mM each dNTP, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 300 nM primers HIST1-5 and HIST1-6 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), 1× Expand High Fidelity buffer, and 2.6 U of Expand High Fidelity enzyme mix. The PCR cycling conditions were 94°C for 5 min and then 35 cycles of 94°C for 35 s, 60°C for 35 s, and 68°C for 6 min, followed by a final extension at 68°C for 10 min. The final construct was gel purified and quantified as described above before transformation into protoplasts of F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici strain 4287, according to a protocol described previously (13).

Tagging with the monomer ChFP (6, 51) was completed using identical methods and the phleomycin resistance (Phler) cassette as a selectable marker (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). Hygr and Phler transformants were routinely subjected to two consecutive rounds of single sporing and stored as microconidia at −80°C.

Microscopy.

For light microscopy analysis of nuclear division patterns, a Leica DMI6000b inverted microscope driven by MetaMorph 6.3r7 software (Molecular Devices Corp., Downingtown, PA) and equipped with a Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.40-numerical-aperture (NA) oil differential interference contrast (DIC) objective (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), a specific filter for GFP (Leica Microsystems), and a heating insert P (PeCon GmbH, Germany) was used. Samples were inoculated in glass-bottom petri dishes with liquid medium and incubated at 28°C. Images were recorded using a Hamamatsu Orca-ERII camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan) at ×630 magnification every 30 s and sequentially for GFP fluorescence (GF), with Nomarski optics. To depict nuclear distribution and movement after mitosis, kymographs were performed using the application integrated in Metamorph software. To measure the speed of moving structures in image time series (two dimensional [2D] over time), a line-type region of interest (ROI) was specified by hand drawing and read out. From these lines of gray values, the kymograph was assembled as a time/space/plot drawing, where each line is the ROI from every frame of the time series in order from the top to the bottom. The y axis is a time axis, where the unit is nm min−1, while the x axis represents the distance along the line ROI, where the unit is the pixel size or length unit of the image/sequence. A moving structure will be visible as a contrast edge in the kymograph. Thus, speed (displacement per time interval) can be measured if a line is traced along the edge. Based on time series stacks, a region was selected over the hyphae using the tool “line” with a factor of 24, which usually covered the width of all cell compartments analyzed. The maximum pixel intensity was displayed along the selected region.

For fluorescence video microscopy analysis of germination, hyphal fusions, and conidiation, 40-μl droplets containing a mixture of 1.25 × 106 spores ml−1 of each fungal strain harboring either FoH1::GFP or FoH1::ChFP were inoculated on glass slides covered with a thin layer of solid medium, covered with a coverslip, and incubated at 28°C for up to 18 h. Images were taken as described previously (28) using an Axioplan2 microscope equipped with the objectives Plan-Apochromat 100×/1.40-NA oil DIC and Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.40-NA oil DIC (Carl Zeiss AG, Feldbach, Switzerland) and appropriate filters (Zeiss and Chroma Technology, Brattleboro, VT) and a cooled charge-coupled device camera CoolSnap HQ (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) with MetaMorph 6.2r6 software (Molecular Devices Corp., Downingtown, PA). Images were colored and overlaid by using Overlay Images and exported from MetaMorph as 8-bit grayscale or RGB TIFF files. Z-stacks and time-lapse picture series were converted to QuickTime MPEG-4 movies with Quicktime Player Pro (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA).

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), 2-week-old cultivar Monika tomato seedlings (Novartis Seeds) were inoculated with F. oxysporum strains by immersing the roots in a suspension of 5 × 106 spores ml−1 and incubated at 28°C with shaking at 80 rpm for 24 h. Five-millimeter sections of infected roots were fixed for 2 h in 2% glutaraldehyde at room temperature and dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (30 to 100%), followed by 100% acetone for critical-point drying. Samples were coated with a thin gold layer and observed with a Jeol 6300 scanning electron microscope.

RESULTS

Germination and hyphal fusions of F. oxysporum during infection of tomato roots.

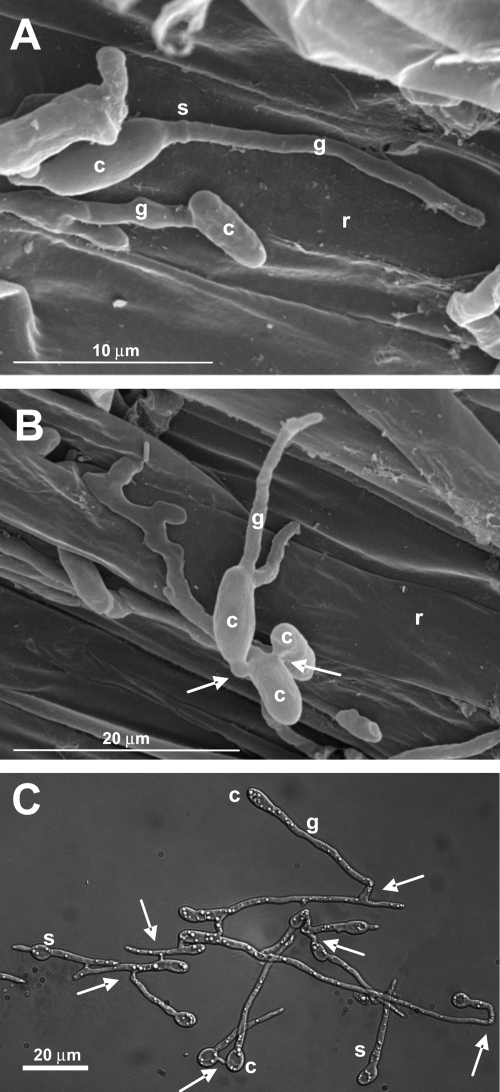

During early stages of infection, F. oxysporum adheres to the root surface, differentiates infection hyphae, and directly penetrates the root (11, 38a). Figure 1 shows scanning electron microscopy micrographs of tomato roots inoculated with F. oxysporum microconidia. Extremely thin germ tubes, which can reach a diameter of around 1 μm, emerged from the end of oval microconidia adhering to the surface of the root (Fig. 1A), followed by formation of a septum separating the germ tube from the conidium. The pattern of conidial germination was preferentially unipolar, with most microconidia producing a single germ tube (91.3% unipolar; n = 104). Vegetative hyphal fusions between germ tubes (arrows) were frequently observed during early stages of infection (Fig. 1B). We noted that in PDB diluted 1:50 in 20 mM glutamic acid, F. oxysporum produced very thin germ tubes and frequent hyphal fusions similar to those observed on tomato roots (Fig. 1C). Moreover, under these nutrient-limiting conditions, the germination mode was also preferentially unipolar (64%; n = 72), in contrast to nutrient-rich medium (PDB), where 97% of the conidia displayed a bidirectional pattern (n = 176) (see Fig. S1C in the supplemental material). Different modes of germination were previously reported in the plant pathogen Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, whose conidia show unipolar germination on the plant or on pea extract but bipolar germination on nutrient-rich medium (4). Based on these results, we decided to use microconidial germination on agar surfaces of PDB diluted 1:50 in 20 mM glutamic acid to perform live-cell imaging of nuclear dynamics during early developmental stages of F. oxysporum.

Fig. 1.

(A and B) Scanning electron micrographs of tomato roots 24 h after inoculation with F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici isolate 4287. (C) Light microscopy image of isolate 4287 grown for 15 h in PDB diluted 1:50 in 20 mM glutamic acid. c, conidium; g, germ tube; r, root surface; s, septum. The arrows indicate conidial anastomosis tubes.

Fluorescent labeling of histone H1 with GFP and ChFP in F. oxysporum.

To study the distribution of nuclei, a possible coordination of nuclear division with septation, and the fate of nuclei after hyphal fusions, it was essential to construct two strains with differently labeled nuclei. To this end, the C terminus of FoH1 was fused with either GFP or ChFP using PCR gene targeting (55) (see Fig. S1A and B in the supplemental material). Around 40% of the transformants carried a correctly targeted FoH1::GFP (green) or FoH1::ChFP (red) fusion at the endogenous locus, as determined by PCR and Southern hybridization analysis (see Fig. S1C in the supplemental material). The tagged transformants displayed normal hyphal growth and colony morphology, indicating that the C-terminal fusions to FoH1 did not interfere with basic functions of FoH1. Fluorescence microscopy analysis and comparative DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining showed that green and red fluorescence was restricted to nuclei (see Fig. S1D in the supplemental material). In both types of fusion proteins, the subnuclear localization displayed a nonhomogeneous dynamic distribution (see Movie S1 in the supplemental material). Analysis of 30 nuclei revealed 4 to 9 mobile fluorescent foci, much less than the 15 chromosomes per haploid genome (https://www.broad.mit.edu/). The peripheral localization of these foci suggests a possible association of histone H1, and thus chromatin, with the internal surface of the nuclear envelope.

Timing of mitoses and septum formation during early developmental stages of F. oxysporum.

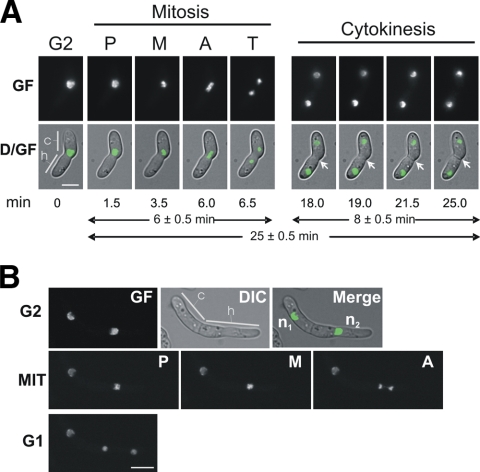

Figure 2 A and Movie S2 in the supplemental material show the first mitosis and septum formation in a germinating microconidium. At the onset of mitosis, green fluorescence accumulated at the center of the nucleus, most likely representing prophase and the start of metaphase (1.5 to 3.5 min). The phase showing a maximum of fluorescence condensation was considered metaphase, although individual chromosomes could not be distinguished with the 63× or 100× objectives. Migration of fluorescence to the two poles marked the segregation of chromosomes to the two daughter nuclei (anaphase), the shortest phase (0.5 to 1 min). The total length of mitosis was approximately 6 min. After completion of mitosis, green fluorescence started to decondense in the daughter nuclei and adopted a partially aggregated distribution similar to the interphase. Following mitosis, the two daughter nuclei moved in opposite directions to localizations fairly distant from that at the start of mitosis, and a septum (Fig. 2A, white arrows) formed very close to the site of mitosis 12 min after the onset of nuclear separation. Figure 2B shows an example of the second mitosis with fluorescence condensation restricted to the dividing nucleus.

Fig. 2.

Live-cell imaging of mitoses after conidial germination. (A) First nuclear division in a germling of a FoH1::GFP strain. Images were recorded consecutively for GF and Nomarski optics (DIC) (see Materials and Methods). D/GF, merged images for DIC and GF. Conidial (c) and hyphal (h) compartments are indicated. Mitotic phases are indicated as follows: P, prophase, M, metaphase, A anaphase, and T, telophase. After karyokinesis, the formation of a septum was visualized (arrows). Scale bar, 5 μm. The time in minutes at which each micrograph was taken (see Movie S2 in the supplemental material) and the average times for mitosis and cytokinesis are indicated below the images. (B) Second nuclear division in a FoH1::GFP strain. The upper row shows fluorescence (GF), DIC, and merged images of a cell with two compartments at G2 stage. Nuclei are indicated as n1 and n2. Note that while n1 remains interphasic, n2 undergoes mitosis. Samples were grown and imaged as described for panel A. Mitotic phases (MIT) and cell type are indicated. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Table 1 summarizes the timing of the first, second, and third mitoses and the lengths of growing germ tubes. At the time of the first mitosis, the germ tube had extended to a length of 6.6 ± 0.4 μm. The second mitosis occurred when the germ tube had elongated to 17.28 ± 0.9 μm, indicating an acceleration of hyphal growth between the first and second nuclear divisions. This trend was maintained in subsequent mitoses, concomitant with a reduction in hyphal diameter to 1.2 μm (Fig. 3 A and Table 1). In these experiments, the time between the first and second mitoses was 177.1 ± 12.8 min, and both the first and second nuclear divisions occurred within 6 ± 0.5 min, confirming a previous report in which an average duration of 6 min was determined by electron microscopy analysis (1, 2). Similar to the first mitosis, a septum formed at or slightly apical to the site of the second mitosis 13 ± 2 min after the onset of nuclear separation. This spatial and temporal control of cytokinesis was also observed for later mitoses during hyphal elongation (see below), resulting in one nucleus per hyphal compartment. This implies that nuclei in subapical compartments should be mitotically silent, which is directly testable by monitoring nuclear divisions and the formation of septa.

Table 1.

Biological measurements taken during vegetative hyphal growth

| Parameter | Mean value | Standard error | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of microconidium before emergence of germ tube (μm) | 4.51 | 0.16 | 23 |

| Length of germ tube at start of first nuclear division (μm) | 6.55 | 0.40 | 22 |

| Length of germ tube at start of second nuclear division (μm) | 17.17 | 0.92 | 17 |

| Length of germ tube at start of third nuclear division (μm) | 30.49 | 0.68 | 5 |

| Distance between first and second septa | 7.50 | 0.36 | 19 |

| Distance between second and third septa | 11.10 | 0.61 | 11 |

| Distance between third and fourth septa | 15.07 | 1.12 | 4 |

| Hyphal diam (μm), 2 μm behind the tip at first mitosis | 1.55 | 0.04 | 19 |

| Hyphal diam (μm), 2 μm behind the tip at second mitosis | 1.31 | 0.04 | 13 |

| Hyphal diam (μm), 2 μm behind the tip at third mitosisa | 1.22 | 0.04 | 8 |

| Time elapsed between germination and first nuclear division (min) | 215.7 | 25.2 | 23 |

| Time elapsed between first and second nuclear divisions (min) | 177.1 | 12.8 | 16 |

| Time elapsed between second and third nuclear divisions (min) | 156.2 | 11.9 | 13 |

| Time elapsed between third and fourth nuclear divisions (min) | 131.6 | 4.5 | 5 |

| Time between nuclear division and septum formation (min) | 19.0 | 0.34 | 23 |

| Ratio between distance covered by apical vs basal nuclei from the mitosis start site | 2.61 | 0.30 | 14 |

Hyphal diameter did not vary significantly during subsequent mitoses.

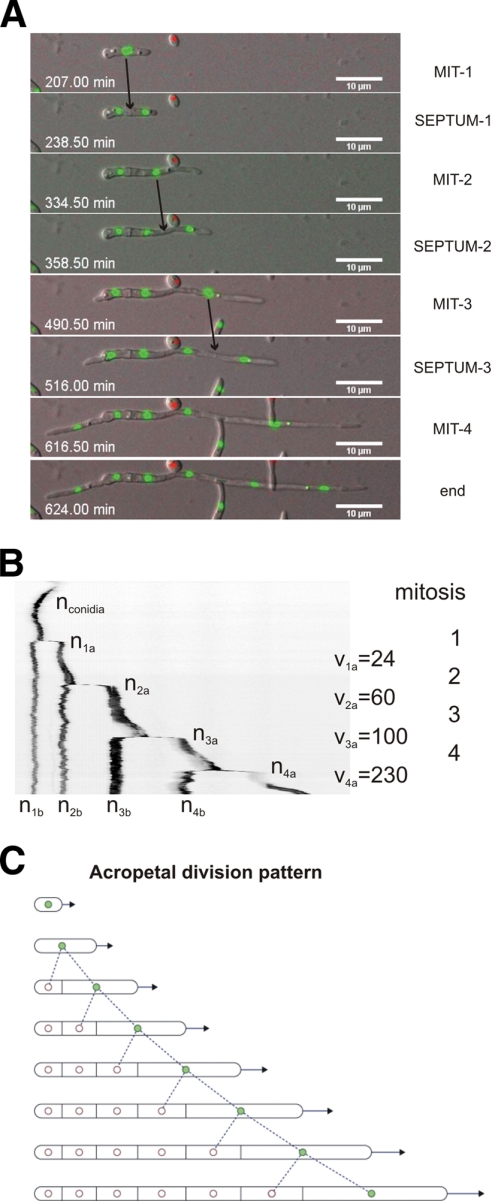

Fig. 3.

Patterns of nuclear division in F. oxysporum. (A) Series of images of a developing hypha from Movie S3 in the supplemental material showing 4 consecutive mitoses, each followed by formation of a septum. The time in minutes (seconds in decimal scale) is documented in Movie S3 in the supplemental material. The images were acquired using an Axioplan2 microscope equipped with appropriate filters and a CoolSnap HQ camera at room temperature (RT) every 90 s for 15 h simultaneously for GFP and ChFP fluorescence and Nomarski optics, and merged for DIC and green and red fluorescence. (B) Kymograph of nuclear fluorescence (inverted image), using the Metamorph software package, from a selected hypha. Note that mitosis occurs exclusively in the apical compartment of a vegetatively growing hypha, generating one mitotically active daughter nucleus (shown in green in the diagram in panel C) and one mitotically dormant daughter nucleus (in white in the diagram in panel C). The mitotically active nucleus is located in the apical compartment (indicated as nxb, where x is the mitosis number) and the dormant nucleus in the subapical compartment (indicated as nxa, where x is the mitosis number). The speed of the apical nucleus after mitosis and apical-compartment elongation (vx) is indicated in nm min−1. (C) Model of the process. Filled circles, active nuclei; empty circles, dormant nuclei.

Acropetal nuclear pedigree in elongating hyphae.

Movie S3 in the supplemental material, together with Fig. 3A and B, presents compelling evidence that only the apical daughter nucleus remains mitotically competent. Each dividing nucleus generated one mitotically active and one mitotically dormant daughter nucleus in an acropetal mode, whereby the active nucleus was located in the apical and the dormant in the subapical compartment (Fig. 3C shows the model). This pattern contrasts with the “mitotic waves” previously reported for this species (2). We were able to monitor up to 6 subsequent nuclear cycles in multiple hyphae. Septa were formed within 19 ± 0.34 min after the onset of mitosis at or slightly apical of the position of the dividing nucleus. Interestingly, the cycle time decreased by 12 to 16% after each mitosis (Table 1). In contrast, the distance between previous and subsequent sites of mitosis and septation increased by 36 to 48% for each cycle, concomitant with increments in the hyphal elongation rate and in the speed of the apical daughter nucleus moving along the apical compartment (Fig. 3B and Table 1).

Basopetal nuclear pedigree during conidiation.

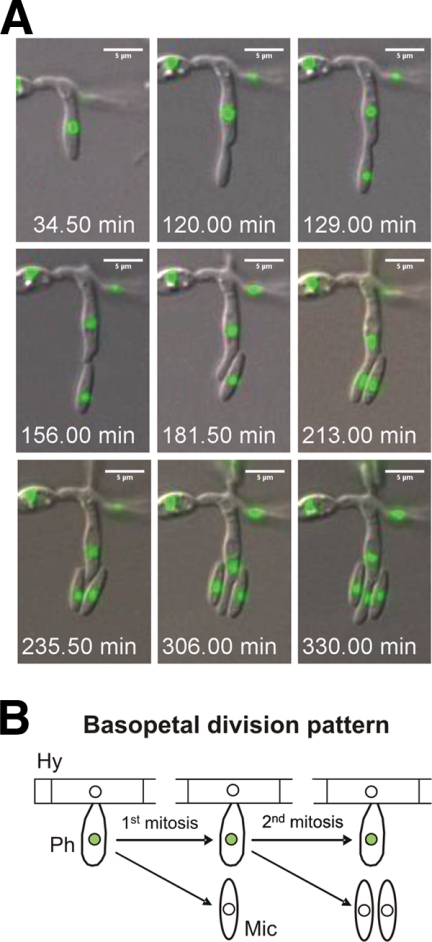

The long-time movies allowed to follow conidiation on agar surfaces, a process not induced on the surfaces of tomato roots. Asexual development in F. oxysporum starts with the formation of a sporogenous specialized cell (termed a phialide), committed to the formation of microconidia, from a previously mitotically inactive compartment. Phialide cells exhibited a distinct, basopetal mode of division. The daughter nucleus inside the newly formed microconidium was mitotically dormant, while the subapical nucleus in the phialide cell remained mitotically active for multiple additional divisions, each generating a microconidium with a single mitotically dormant nucleus (Fig. 4 A and B; see Movie S4 in the supplemental material). Nuclear division occurred when the microconidium compartment formed by apical extension of the phialide reached its final length of 4 ± 0.2 μm (n = 16 microconidia) (Table 2). At that time, the phialide nucleus divided and one daughter nucleus moved into the microconidium compartment, followed by abscission of the conidium. In contrast to germ tubes, phialides showed a constant time of mitotic cycles that was 30 to 48% shorter than that of vegetative hyphal growth (Tables 1 and 2).

Fig. 4.

(A) Series of images from Movie S4 in the supplemental material showing the formation of microconidia. The time in minutes (seconds in decimal scale) is documented in Movie S4 in the supplemental material. (B) During conidiation, the apical daughter nucleus (located inside the new microconidium) is mitotically dormant, while the subapical nucleus (located inside the phialide) remains mitotically active for several additional divisions. Filled circles, active nuclei; empty circles, dormant nuclei; Hy, hypha; Ph, phialide; Mic, microconidium.

Table 2.

Biological measurements taken during conidiation

| Parameter | Mean value | Standard error | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of microconidium at the time of nuclear division (μm) | 4.0 | 0.2 | 16 |

| Length of released microconidium (μm) | 4.2 | 0.3 | 16 |

| Time elapsed between microconidium emergence and nuclear division (min) | 64.5 | 6.3 | 16 |

| Time elapsed between microconidium emergence and release (min) | 96.3 | 9.2 | 16 |

| Time between nuclear divisions (min) | 92.0 | 3.1 | 8 |

| Time between nuclear divisions and microconidium release (min) | 34.0 | 1.5 | 9 |

Vegetative hyphal fusion triggers nuclear division and invasion, followed by degradation of the resident nucleus.

To analyze nuclear dynamics during vegetative hyphal fusion, a mixture of germinating microconidia harboring either FoH1::GFP (green) or FoH1::ChFP (red) was monitored for 18 h by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5 and 6; see Movies S5, S6, S7, and S8 in the supplemental material). Fusion events were detected between strains harboring either the same or different fluorescent tags (35.3% green-green, 17.6% red-red, and 47.1% green-red; n = 34). As reported previously (39), we frequently observed directed growth of fusing germ tubes toward each other (two examples are shown in Fig. 5B and 6). Hyphal fusions occurred either tip to tip or tip to side, according to the terminology used by Hickey et al. (24). Fusion bridge formation was completed within an average time of 28.8 ± 9.1 min (n = 10) between the start of anastomosis tube emergence and the connection of the two cell compartments.

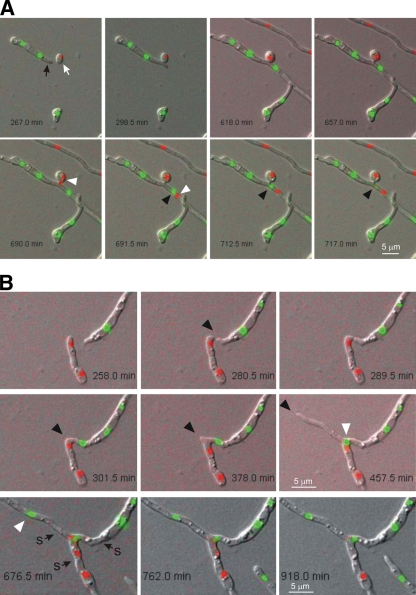

Fig. 5.

Examples of tip-to-tip and tip-to-side vegetative hyphal fusions. (A) Series of images from Movie S5 in the supplemental material showing an example of tip-to-side fusion between a GFP-tagged hyphal compartment (black arrow) and a ChFP-tagged germinating conidium (white arrow). After fusion, the ChFP-tagged nucleus divides, and one daughter nucleus (white arrowheads) migrates through the fusion bridge into the neighboring cell, moving past a GFP-tagged nucleus (black arrowheads), whose fluorescence disappears after 25 min. (B) Series of images from Movies S6 and S7 in the supplemental material showing an example of tip-to-tip fusion. Two apical cells home toward each other (black arrowheads), fuse, and converge into a single hyphal compartment led by the mitotically active, GFP-tagged nucleus (white arrowheads). Note that after fusion, both a GFP- and a ChFP-tagged nucleus coexist inside the same cell for approximately 429 min, followed by degradation of the ChFP-tagged nucleus. s, septum.

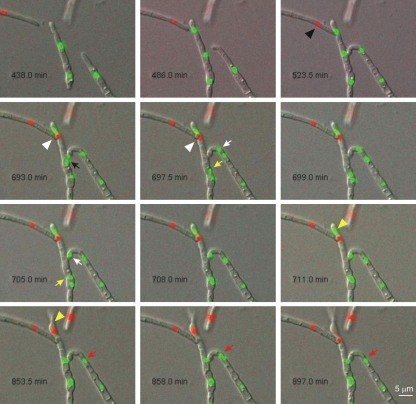

Fig. 6.

Series of images from Movie S8 in the supplemental material showing 2 quasisynchronous fusion events (1 and 2) involving three different hyphae. During fusion event 1 between the two FoH1::GFP hyphae (tip to side), a green fluorescent nucleus (black arrow) divides, and one of the daughter nuclei (white arrow) migrates through the fusion bridge to invade the neighboring cell, while the other daughter nucleus (yellow arrow) invades the underlying hyphal cell. After an extended period (156 min), the nucleus that invaded the neighboring hypha moves back through the fusion bridge to its original cell compartment, while the nuclei in the underlying cell compartment are visible as a single fluorescent spot throughout the rest of the movie. Note that the nucleus inside the neighboring recipient cell (red arrows) divides again and that one of the daughter nuclei is immediately degraded. During fusion event 2 between the FoH1-GFP and the FoH1-ChFP hyphae (tip-to-tip VHF), a red fluorescent nucleus (black arrowhead) divides and one of the daughter nuclei (white arrowheads) invades the adjacent FoH1-GFP hypha. After 95 min, the resident green fluorescent nucleus (yellow arrowhead) is degraded and the red fluorescent nucleus persists inside the cell and subsequently divides while the hypha continues to grow.

Each fusion event was followed by a nuclear division inside one of the interconnected compartments after a variable time period (81.0 ± 30.6 min; n = 7) (Fig. 5 and 6; see Movies S5, S6, and S8 in the supplemental material). The postfusion nuclear division was followed by rapid (1.9 ± 0.5 min; n = 14) migration of one daughter nucleus through the fusion bridge into the adjacent cellular compartment. Figure 5A shows a typical example of tip-to-side fusion between a GFP-tagged hyphal compartment (black arrow) and a ChFP-tagged germinating conidium (white arrow). After fusion, the ChFP-tagged nucleus divides, and one daughter nucleus (white arrowheads) migrates through the fusion bridge into the neighboring cell, moving past a GFP-tagged nucleus (black arrowheads).

Strikingly, migration of the new daughter nucleus into the neighboring cell triggered the degradation of the resident nucleus, as detected by loss of fluorescence. Postfusion nuclear degradation always affected the resident, not the invading nucleus (100%; n = 12). The time period between nuclear invasion and degradation of the resident nucleus was highly variable (112.9 ± 37.6 min; n = 9). For example, in Fig. 5A, the fluorescence of the resident green nucleus (black arrowhead) disappears 25 min after migration of the invading red nucleus through the fusion bridge, whereas in Fig. 5B, the green and red nuclei coexist inside the same cell for 429 min before the red nucleus is finally degraded. Throughout this study, nuclear degradation in intact hyphae was observed only after postfusion nuclear division and migration through the anastomosis tube, suggesting that this process represents a distinct cellular program that is intimately linked to vegetative hyphal fusion.

DISCUSSION

Distinct nuclear pedigrees during development of F. oxysporum.

In the present work, we used fluorescent labeling of F. oxysporum histone H1 to carry out, for the first time, live-cell imaging of nuclear dynamics during different stages of development, including conidial germination, hyphal elongation, septation, conidiation, and anastomosis. The spatial and temporal control of cytokinesis observed during microconidial germination and hyphal development suggest that site selection for the cytokinesis machinery is controlled by mitosis and by cell size cues. Interestingly, the acceleration of hyphal growth between the first and the subsequent mitoses was associated with a reduction in hyphal diameter, and thus, with an increased level of nuclear contraction prior to anaphase. We speculate that the differentiation of extremely thin hyphae might be relevant for a fungal pathogen like F. oxysporum, which lacks appressoria and enters the host by direct penetration of the root surface (37). A recent study in N. crassa reported a similar acceleration pattern, where mitosis was 3 to 4 times faster in germ tubes than in nongerminated macroconidia (45). It was suggested that these differences could be due to the fact that most nuclei were arrested in G1 or G2 during transcription of genes required for germination.

Our studies revealed the presence of two distinct nuclear pedigrees of mitotic activity and dormancy in F. oxysporum. Asexual conidiation follows the typical basopetal pattern of a stem cell lineage, analogous to conidiation in A. nidulans (50). On the other hand, vegetative hyphal cells maintain a strictly acropetal pattern, defining F. oxysporum as a mononucleated mycelial organism. We predict the presence of refined regulatory mechanisms in this fungus, where cellular volume, compartmentalization, and cell cycle regulatory check points govern a mycelial organization different from that of other filamentous fungal models.

Vegetative hyphal fusion triggers nuclear division, migration, and degradation.

F. oxysporum has been known for many years to undergo vegetative hyphal fusion (27, 32). In the model fungus N. crassa, live-cell imaging was used to follow hyphal fusion during different developmental stages, including mature colonies and germinating conidia (24), and more recently, during early stages of colony initiation (45). This approach proved to be highly useful, shedding new light on crucial processes, such as homing of conidial anastomosis tubes (14, 44). However, little is known about the nuclear dynamics during vegetative hyphal fusion. Here, we provide evidence for a previously unreported cellular mechanism that is activated in F. oxysporum after vegetative fusion of two uninucleated cell compartments. The process consists of a nuclear division, followed by migration of an “invading nucleus” through the anastomosis bridge and subsequent degradation of the resident nucleus. Degradation of nuclear DNA has been reported as part of heterokaryon incompatibility (31), a process in which fusion cells between fungal strains carrying different het loci undergo compartmentalization and programmed cell death (17). However, no nuclear degradation has been reported in compatible self-pairings. Interestingly, vegetative hyphae in several basidiomycete species, such as Schizophyllum commune (52), Coriolus versicolor (3), Coprinus cinereus (5), or Typhula trifolii (35), undergo a process termed “nuclear degeneration,” whereby two fusing binucleated cells display a donor-recipient relationship in which both nuclei of the recipient cell degenerate and are replaced by a normal conjugate division of the donor pair (3, 52). At present, the functional relationship between nuclear degeneration in basidiomycetes and fusion-induced nuclear degradation in F. oxysporum remains unclear.

Although vegetative hyphal fusion in F. oxysporum is not essential for plant infection, it contributes to efficient colonization of the root surface, probably because the establishment of a hyphal network allows optimization of virulence-related functions, such as efficient adhesion, exploitation of limited nutrient resources, or competition with other soil microorganisms (39). A second suggested role of hyphal fusion in pathogenicity is the generation of genetic variability through the transfer of DNA, or even entire chromosomes, among different fungal isolates (43, 47). Such a mechanism is particularly important in pathogens that lack a known sexual cycle, such as F. oxysporum. In the present study, we examined only nuclear behavior after hyphal fusion between self-compatible strains. Our results suggest that this fungus contains a highly elaborate mechanism for restoring nuclear numbers and maintaining cell integrity after hyphal fusion. These observations raise a number of questions regarding the origin and role of postfusion nuclear degradation, as well as about the signals that trigger the process and, above all, about how two genetically identical nuclei sharing a common cytoplasm can undergo such radically distinct developmental programs. Further studies addressing these questions should help to unravel the intricacies of the hyphal fusion process in F. oxysporum.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by Junta de Andalucía (AGR 209), the Swiss National Science Foundation (31003A-112688), and Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación grants BIO2007-62661 to A.D.P. and BFU2006-04185(BMC) and BFU2009-08701(BMC) to E.A.E.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 11 June 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aist J. R. 1969. The mitotic apparatus in fungi, Ceratocystis fagacearum and Fusarium oxysporum. J. Cell Biol. 40:120–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aist J. R., Williams P. H. 1972. Ultrastructure and time course of mitosis in the fungus Fusarium oxysporum. J. Cell Biol. 55:368–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aylmore R. C., Todd N. K. 1984. Hyphal fusion in Coriolus versicolor, p. 103–125 InJennings D. H., Rayner A. D. M. (ed.), The ecology and physiology of the fungal mycelium. Symposium of the British Mycological Society. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barhoom S., Sharon A. 2004. cAMP regulation of “pathogenic” and “saprophytic” fungal spore germination. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41:317–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bensaude M. 1918. Récherches sur le cycle évolutive et la sexualité chez les Basidiomycétes. Ph.D. thesis. University of Paris, Nemours, France [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell R. E., Tour O., Palmer A. E., Steinbach P. A., Baird G. S., Zacharias D. A., Tsien R. Y. 2002. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:7877–7882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clutterbuck A. J. 1970. Synchronous nuclear division and septation in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 60:133–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Correll J. C., Puhalla J. E., Schneider R. W., Kraft J. M. 1985. Differentiating races of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. pisi based on vegetative compatibility. Phytopathology 75:1347 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Couteaudier Y., Alabouvette C. 1990. Survival and inoculum potential of conidia and chlamydospores of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lini in soil. Can. J. Microbiol. 36:551–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.d'Enfert C. 1997. Fungal spore germination: insights from the molecular genetics of Aspergillus nidulans and Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 21:163–172 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Pietro A., Garcia-Maceira F. I., Meglecz E., Roncero M. I. G. 2001. A MAP kinase of the vascular wilt fungus Fusarium oxysporum is essential for root penetration and pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1140–1152 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Pietro A., Madrid M. P., Caracuel Z., Delgado-Jarana J., Roncero M. I. G. 2003. Fusarium oxysporum: exploring the molecular arsenal of a vascular wilt fungus. Mol. Plant Pathol. 4:315–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Pietro A., Roncero M. I. G. 1998. Cloning, expression, and role in pathogenicity of pg1 encoding the major extracellular endopolygalacturonase of the vascular wilt pathogen Fusarium oxysporum. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 11:91–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fleissner A., Leeder A. C., Roca M. G., Read N. D., Glass N. L. 2009. Oscillatory recruitment of signaling proteins to cell tips promotes coordinated behavior during cell fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:19387–19392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gladfelter A. 2006. Nuclear anarchy: asynchronous mitosis in multinucleated fungal hyphae. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:547–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gladfelter A. S., Hungerbuehler A. K., Phillipsen P. 2006. Asynchronous nuclear division cycles in multinucleated cells. J. Cell Biol. 172:347–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glass N. L., Dementhon K. 2006. Non-self recognition and programmed cell death in filamentous fungi. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:553–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant M., Mansfield J. 1999. Early events in host-pathogen interactions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2:312–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardham A. R. 2001. Cell biology of fungal infection of plants., p. 90–123 InHoward R., Gow N. (ed.), Biology of the fungal cell. The mycota XIII. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris S. D. 1999. Morphogenesis is coordinated with nuclear division in germinating Aspergillus nidulans conidiospores. Microbiology 145:2747–2756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris S. D. 2005. Morphogenesis in germinating Fusarium graminearum macroconidia. Mycologia 97:880–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris S. D., Morrell J. L., Hamer J. E. 1994. Identification and characterization of Aspergillus nidulans mutants defective in cytokinesis. Genetics 136:517–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hickey P., Read N. (ed.). 2003. Biology of living fungi. British Mycological Society, Kew, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hickey P. C., Jacobson D. J., Read N. D., Glass N. L. 2002. Live-cell imaging of vegetative hyphal fusion in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 37:109–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobson D. J., Gordon T. R. 1988. Vegetative compatibility and self-incompatibility within Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. melonis. Phytopathology 78:668–672 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katan T., Shlevin E., Katan J. 1997. Sporulation of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici on stem surface of tomato plants and aerial dissemination of inoculum. Phytopathology 87:712–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Köhler E. 1930. Ur Kenntnis der vegetativen Anastomosen der Pilze. II. Mitteilung. Planta 10:495–522 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Köhli M., Galati V., Boudier K., Roberson R. W., Philippsen P. 2008. Growth-speed-correlated localization of exocyst and polarisome components in growth zones of Ashbya gossypii hyphal tips. J. Cell Sci. 121:3878–3889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loo M. 1976. Some required events in conidial germination of Neurospora crassa. Dev. Biol. 54:201–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maheshwari R. 2005. Nuclear behavior in fungal hyphae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 249:7–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marek S. M., Wu J., Glass N. L., Gilchrist D. G., Bostock R. M. 2003. Nuclear DNA degradation during heterokaryon incompatibility in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 40:126–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mesterhazy A. 1973. The morphology of an undescribed form of anastomosis in Fusarium. Mycologia 65:916–919 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minke P. F., Lee I. H., Plamann M. 1999. Microscopic analysis of Neurospora ropy mutants defective in nuclear distribution. Fungal Genet. Biol. 28:55–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Momany M., Taylor I. 2000. Landmarks in the early duplication cycles of Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus nidulans: polarity, germ tube emergence and septation. Microbiology 146:3279–3284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noble M. 1937. The morphology and cytology of Typhula trifolii (Rostr.). Ann. Bot. 1:67–98 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nucci M., Anaissie E. 2002. Cutaneous infection by Fusarium species in healthy and immunocompromised hosts: implications for diagnosis and management. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:909–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olivain C., Alabouvette C. 1999. Process of tomato root colonization by a pathogenic strain of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici in comparison with a non-pathogenic strain. New Phytol. 141:497–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ortoneda M., Guarro J., Madrid M. P., Caracuel Z., Roncero M. I. G., Mayayo E., Di Pietro A. 2004. Fusarium oxysporum as a multihost model for the genetic dissection of fungal virulence in plants and mammals. Infect. Immun. 72:1760–1766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38a.Pareja-Jaime Y., Martin-Urdiroz M., Gonzalez-Roncero M. I., Gonzalez-Reyes J. A., Ruiz-Roldan M. C. 2010. Chitin synthase-deficient mutant of Fusarium oxysporum elicits tomato plant defence response and protects against wild-type infection. Mol. Plant Pathol. 11:479–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prados Rosales R. C., Di Pietro A. 2008. Vegetative hyphal fusion is not essential for plant infection by Fusarium oxysporum. Eukaryot. Cell 7:162–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Puhalla J. E. 1985. Classification of strains of Fusarium oxysporum on the basis of vegetative compatibility. Can. J. Bot. 63:179–183 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Read N. D., Fleißner A., Roca M. G., Glass N. L. 2010. Hyphal fusion, p. 260–273 InBorkovich K. A., Ebbole D. (ed.), Cellular and molecular biology of filamentous fungi. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 42.Requena N., Alberti-Segui C., Winzenburg E., Horn C., Schliwa M., Philippsen P., Liese R., Fischer R. 2001. Genetic evidence for a microtubule-destabilizing effect of conventional kinesin and analysis of its consequences for the control of nuclear distribution in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 42:121–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roca M. G., Read N. D., Wheals A. E. 2005. Conidial anastomosis tubes in filamentous fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 249:191–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roca M. G., Arlt J., Jeffree C. E., Read N. D. 2005. Cell biology of conidial anastomosis tubes in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 4:911–919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roca M. G., Kuo H., Lichius A., Freitag M., Read N. D. 2010. Nuclear dynamics, mitosis and the cytoskeleton during the early stages of colony initiation in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell. doi:10.1128/EC.00329-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosenberger R. F., Kessel M. 1967. Synchrony of nuclear replication in individual hyphae of Aspergillus nidulans. J. Bacteriol. 94:1464–1469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanders I. R. 2006. Rapid disease emergence through horizontal gene transfer between eukaryotes. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21:656–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seong K. Y., Zhao X., Xu J. R., Güldener U., Kistler H. C. 2008. Conidial germination in the filamentous fungus Fusarium graminearum. Fungal. Genet. Biol. 45:389–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Serna L., Stadler D. 1978. Nuclear division cycle in germinating conidia of Neurospora crassa. J. Bacteriol. 136:341–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sewall T. C., Mims C. W., Timberlake W. E. 1990. AbaA controls phialide differentiation in Aspergillus nidulans. Plant Cell 2:731–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shaner N. C., Campbell R. E., Steinbach P. A., Giepmans B. N. G., Palmer A. E., Tsien R. Y. 2004. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp red fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 22:1567–1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Todd N. K., Aylmore R. C. 1985. Cytology of hyphal interactions and reactions in Schizophyllum commune, p. 231–248 InCasselton D., Casselton L. A. (ed.), Developmental biology of the Agarics, vol. 10 Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tucker S. L., Talbot N. J. 2001. Surface attachment and pre-penetration stage development by plant pathogenic fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 39:385–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wolkow T. D., Harris S. D., Hamer J. E. 1996. Cytokinesis in Aspergillus nidulans is controlled by cell size, nuclear positioning and mitosis. J. Cell Sci. 109:2179–2188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang L., Ukil L., Osmani A., Nahm F., Davies J., De Souza C. P. C., Dou X. W., Perez-Balaguer A., Osmani S. A. 2004. Rapid production of gene replacement constructs and generation of a green fluorescent protein-tagged centromeric marker in Aspergillus nidulans. Eukaryot. Cell 3:1359–1362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.