Abstract

An analytical system based on rRNA-targeted reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) for enumeration of catalase-negative, Gram-positive cocci was established. Subgroup- or species-specific primer sets targeting 16S or 23S rRNA from Enterococcus, Streptococcus, and Lactococcus were newly developed. The RT-qPCR method using these primers together with the previously reported primer sets specific for the Enterococcus genus, the Streptococcus genus, and several Streptococcus species was found to be able to quantify the target populations with detection limits of 103 to 104 cells per gram feces, which was more than 100 times as sensitive as the qPCR method (106 to 108 cells per gram feces). The RT-qPCR analysis of fecal samples from 24 healthy adult volunteers using the genus-specific primer sets revealed that Enterococcus and Streptococcus were present as intestinal commensals at population levels of log10 6.2 ± 1.4 and 7.5 ± 0.9 per gram feces (mean ± standard deviation [SD]), respectively. Detailed investigation using species- or subgroup-specific primer sets revealed that the volunteers harbored unique Enterococcus species, including the E. avium subgroup, the E. faecium subgroup, E. faecalis, the E. casseliflavus subgroup, and E. caccae, while the dominant human intestinal Streptococcus species was found to be S. salivarius. Various Lactococcus species, such as L. lactis subsp. lactis or L. lactis subsp. cremoris, L. garvieae, L. piscium, and L. plantarum, were also detected but at a lower population level (log10 4.6 ± 1.2 per gram feces) and prevalence (33%). These results suggest that the RT-qPCR method enables the accurate and sensitive enumeration of human intestinal subdominant but still important populations, such as Gram-positive cocci.

Enterococci, streptococci, and lactococci are catalase-negative, Gram-positive cocci that are usually facultative anaerobes. Although these genera were originally classified as the single genus Streptococcus, extensive nucleic acid hybridization studies and comparative oligonucleotide cataloguing revealed that the taxon consists of three genetically distinct groups, which is the present widely accepted classification (59-61). These groups belong to the lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and include several beneficial species, such as Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactococcus lactis, and Enterococcus faecalis, which are widely used in fermented food (8, 21, 51). Enterococci and streptococci are members of human intestinal microbiota and are commonly detected in fecal samples of healthy adults as subdominant populations (23, 57). Lactococci, which are the most commonly found bacteria in dairy products (10), have not been regarded as commensals but rather transient bacteria ingested with food (8, 38). On the other hand, some enterococcal and streptococcal species are considered the cause of a variety of infections in humans (48, 57), while lactococci rarely cause human infections (8). Enterococci were traditionally regarded as low-grade pathogens, but they have recently emerged as a leading cause of nosocomial infections, such as urinary tract infections (UTIs) and bloodstream infections (BSIs) (15, 64). The spread of antibiotic-resistant enterococci has also become a major problem worldwide (11, 47). Streptococcal infections, the incidence of which has been less than that of enterococcal infections, include a range of serious infections from dental caries and pharyngitis to life-threatening conditions, such as necrotizing fasciitis and meningitis (46).

These human intestinal catalase-negative, Gram-positive cocci have been mainly enumerated by conventional culture methods (17, 39, 59). These methods involve the use of selective microbiological media, followed by isolation of pure cultures and the application of confirmatory biochemical tests, which are labor-intensive and time-consuming. Although various commercially available test systems have been developed to overcome these shortcomings, there are still significant problems of inaccurate classification and identification owing to the fact that phenotypic tests do not always allow clear results to be obtained (7, 30, 53). Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) and PCR have been adopted as the best cultivation-independent methods for quantitative analysis of human intestinal microbiota and are recognized as having advantages in terms of specificity. The quantitative PCR method (qPCR) with rRNA-targeted primers is one of the most popular methods for identifying predominant bacterial populations (4, 27-29, 44, 45). However, it has been demonstrated that the sensitivity of qPCR is around 105 to 106 cells per gram feces, which does not seem to be sufficient for accurate quantification of subdominant populations in the intestines (103 to 106 cells per gram feces), such as Gram-positive cocci. Recently, high-throughput analysis approaches, such as pyrosequencing and phylogenetic microarrays, have been applied successfully to study the microbial community in the human intestines (2, 9, 12, 54) and allowed estimates of subdominant populations.

Our previous study showed that the reverse transcription (RT)-qPCR method targeting rRNA molecules was more than 100 times as sensitive as the qPCR method targeting the corresponding rRNA gene and enabled the accurate quantification of subdominant bacterial populations in human intestines with detection limits of 102 to 104 cells per gram feces (42, 43). In addition to the previously reported primer sets for the Enterococcus genus (43), the Streptococcus genus, and various associated species (58), we here describe new primer sets that have been developed for quantification of Enterococcus species subgroups, Streptococcus species, and Lactococcus subgroups to analyze the overall bacterial populations of human intestinal Gram-positive cocci. Fecal microbiota of 24 healthy Japanese adults were analyzed by RT-qPCR with these primer sets and the distributions of Enterococcus, Streptococcus, and Lactococcus were investigated in detail.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reference strains and culture conditions.

The strains listed in Table 1 were used in this study. All enterococcal strains were grown anaerobically in MRS broth (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) at 37°C, except that Enterococcus caccae DSM 19114T was grown anaerobically in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Becton Dickinson) at 37°C. Streptococcus bovis JCM 5802T, Streptococcus mutans IFO 13955T, Streptococcus salivarius JCM 5707T, ATCC 9759, and ATCC 13419, Streptococcus thermophilus ATCC 19258T, Streptococcus sanguinis JCM 5708T, Streptococcus sobrinus ATCC 33478T, and Streptococcus intermedius JCM 12996T were grown anaerobically in MRS broth at 37°C, and the other streptococcal strains were grown aerobically in BHI broth at 37°C. Lactococcus garvieae NCFB 2155T, Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis ATCC 19435T, ATCC 11454, ATCC 13675, NCDO 712, and NCDO 509, Lactococcus plantarum ATCC 43199T, and Lactococcus raffinolactis ATCC 43920T were grown anaerobically in MRS broth at 30°C. Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris ATCC 19257T was grown anaerobically in MRS broth at 26°C, and L. lactis subsp. hordniae ATCC 29071T and Lactococcus piscium DSM 6634T were grown aerobically in BHI broth at 30°C and at 20°C, respectively. The CFU counts of E. faecium and L. lactis subsp. lactis were determined by culturing the organism on MRS agar.

TABLE 1.

Specificity tests with the primers

| Taxon | Strain | Reaction with the following primer seta: |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g-Encoc-F/R | s-Efs-F/R | s-Ecacc-F/R | s-Ececo-F/R | sg-Esulf-F/R | g-Ecass-F/R | sg-Eavi-F/R | s-Edis-F/R | sg-Efm-F/R | s-Efm-F/R | g-Str-F/R | s-Sag-F/R | s-Spy-F/R | s-Spn-F/R | s-Ssal-F/R | sg-Lclac-F/R | sg-Lcpis-F/R | ||

| Enterococcus species | ||||||||||||||||||

| E. faecalis | ATCC 19433T | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| E. caccae | DSM 19114T | + | − | + | − | − | − | ± | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| E. cecorum | JCM 8724T | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| E. sulfureus | DSM 6905T | + | − | − | − | + | − | ± | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| E. italicus | DSM 15952T | + | − | − | − | + | − | ± | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| E. casseliflavus | JCM 8723T | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | ± | − | − | ± | − | − | − |

| E. gallinarum | JCM 8728T | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | ± | − | − | ± | − | − | − |

| E. flavescens | ATCC 49996T | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| E. avium | JCM 8722T | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| E. pseudoavium | JCM 8732T | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| E. malodoratus | JCM 8730T | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| E. gilvus | DSM 15689T | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| E. raffinosus | JCM 8733T | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| E. dispar | DSM 6630T | + | − | − | − | − | ± | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| E. durans | GIFU 9960T | + | − | − | − | − | ± | − | ± | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| E. mundtii | JCM 8731T | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| E. faecium | ATCC 19434T | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| E. hirae | ATCC 8043T | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Streptococcus species | ||||||||||||||||||

| S. agalactiae | JCM 5671T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| S. dysgalactiae subsp. dysgalactiae | DSM 20662T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis | LMG 16026T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| S. pyogenes | ATCC 12344T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | ± | − | − | − |

| S. canis | DSM 20715T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| S. equi subsp. equi | DSM 20561T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| S. mitis | GIFU 12458T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| S. pneumoniae | DSM 20566T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| S. oralis | DSM 20627T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | ± | − | − | − |

| S. sanguinis | JCM 5708T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| S. gordonii | DSM 6777T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| S. intermedius | JCM 12996T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| S. anginosus | DSM 20563T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| S. salivarius | JCM 5707T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| S. thermophilus | ATCC 19258T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| S. bovis | JCM 5802T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| S. mutans | IFO 13955T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| S. sobrinus | ATCC 33478T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Lactococcus species | ||||||||||||||||||

| L. garvieae | NCFB 2155T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ± | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| L. lactis subsp. cremoris | ATCC 19257T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ± | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis | ATCC 19435T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ± | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| L. lactis subsp. hordniae | ATCC 29071T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ± | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| L. piscium | DSM 6634T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| L. plantarum | ATCC 43199T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| L. raffinolactis | ATCC 43920T | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

The specificity of the RT-qPCR assay for target bacteria with each primer set was investigated using RNA extracts corresponding to 1010 cells per 10 ml from each strain described. Specificity was judged using the criteria described in Materials and Methods. The amplified signal was judged positive (+) when it was more than that of 109 standard cells and negative (−) when it was less than that of 105 standard cells. Signals between 105 and 109 standard cells were defined as positive and negative (±). The amplified signal was defined as negative (−) when the peak of the corresponding melting curve was different from that of the standard strain. The bacterial species for which each set of primers was designed to target are indicated by boldface plus symbols. In addition, negative PCR results were obtained for the following bacterial strains: Staphylococcus aureus GIFU 9120T, Staphylococcus epidermidis JCM 2414T, Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356T, Bacillus cereus JCM 2152T, Bacillus subtilis JCM 1465T, Ruminococcus productus JCM 1471T, Clostridium indolis JCM 1380T, Clostridium aminovalericum JCM 11016T, Clostridium symbiosum JCM 1297T, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii ATCC 27768T, Clostridium butyricum JCM 1391T, Clostridium paraputrificum JCM 1293T, Clostridium innocuum DSM 1286T, Eubacterium biforme ATCC 27806T, Eubacterium cylindroides DSM 3983T, Eubacterium dolichum DSM 3991T, Clostridium ramosum JCM 1298T, Clostridium cocleatum JCM 1397T, Clostridium spiroforme JCM 1432T, Bacteroides vulgatus ATCC 8482T, Bacteroides ovatus JCM 5824T, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron JCM 5827T, Bifidobacterium adolescentis ATCC 15703T, Bifidobacterium catenulatum ATCC 27539T, Bifidobacterium longum ATCC 15707T, Collinsella aerofaciens ATCC 25986T, Prevotella melaninogenica ATCC 25845T, Escherichia coli ATCC 11775T, Citrobacter freundii JCM 1657T, Klebsiella pneumoniae JCM 1662T, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus JCM 6842T, and Candida albicans IFO 1385T.

Development of rRNA-targeted primers.

The development of rRNA-targeted primers was performed according to the method described by Matsuda et al. (43). We herein constructed nine sets of Enterococcus subgroup- or species-specific primers (for E. faecalis species, E. caccae species, E. cecorum species, E. sulfureus subgroup, E. casseliflavus subgroup, E. avium subgroup, E. dispar species, E. faecium subgroup, E. faecium species), two sets of Lactococcus subgroup-specific primers (L. lactis subgroup and L. piscium subgroup), and a set of Streptococcus species-specific primer (for S. salivarius or S. thermophilus), as shown in Table 2. Dividing the target species into subgroups was conducted based on the 16S rRNA sequence phylogenetic trees, and each primer was designed against the highly conserved regions within each species by comparison of the sequences in silico.

TABLE 2.

16S or 23S rRNA gene-targeted primers used in this study

| Targeta | Primerb | Sequence (5′ tο 3′) | Product size (bp)c | Annealing temp (°C) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterococcus genus | g-Encoc-F | ATCAGAGGGGGATAACACTT | 336 | 55 | 43 |

| g-Encoc-R | ACTCTCATCCTTGTTCTTCTC | ||||

| Enterococcus faecalis | s-Efs-F | CCCGAGTGCTTGCACTCAATTGG | 419 | 60 | This study |

| s-Efs-R | AGGGGACGTTCAGTTACTAACGT | ||||

| Enterococcus caccae | s-Ecacc-F | CCGCATAATAGTCGACACC | 318 | 60 | This study |

| s-Ecacc-R | GTCAAGGTAAGAGCAGTTACTCTCCTA | ||||

| Enterococcus cecorum | s-Ececo-F | TTCCATTTACCGCATGGTAGATGGAT | 311 | 60 | This study |

| s-Ececo-R | CCGTCAAGGGATGAACTTTCCAC | ||||

| Enterococcus sulfureus subgroup | sg-Esulf-F | TTCTTTCTTATCGAACTTCGGTTCA | 410 | 60 | 43 and this study |

| sg-Esulf-R | ACTCTCATCCTTGTTCTTCTC | ||||

| Enterococcus casseliflavus subgroup | sg-Ecass-F | CACTATTTTCCGCATGGAAGAAAG | 311 | 60 | This study |

| sg-Ecass-R | CCGTCAAGGGATGAACATTTTAC | ||||

| Enterococcus avium subgroup | sg-Eavi-F | CAGCATCTTTTATAGGATGTTACTTTTCA | 213 | 60 | This study |

| sg-Eavi-R | GGTCCTTCGACTATCTCACTGG | ||||

| Enterococcus dispar | s-Edis-F | CCGCATAATATTAATGAACTCATGTTT | 318 | 60 | This study |

| s-Edis-R | CCGTCAAGGGATGAACATTTTAC | ||||

| Enterococcus faecium subgroup | sg-Efm-F | AGCTTGCTCCACCGGAAAAAGA | 164 | 60 | This study |

| sg-Efm-R | ATCCATCAGCGACACCSKAA | ||||

| Enterococcus faecium | s-Efm-F | GTCTGTCCAAGCAGTAAGTCTGAAGAG | 65 | 60 | This study |

| s-Efm-R | CATCACAGCTTGTCCTTAAGAAAAG | ||||

| Streptococcus genus | g-Str-F | AGCTTAGAAGCAGCTATTCATTC | 309 | 60 | 58 |

| g-Str-R | GGATACACCTTTCGGTCTCTC | ||||

| Streptococcus agalactiae | s-Sag-F | GTTATTTAAAAGGAGCAATTGCTT | 285 | 60 | 58 |

| s-Sag-R | TTGGTAGATTTTCCACTCCTACCA | ||||

| Streptococcus pyogenes | s-Spy-F | AAGAGAGACTAACGCATGTTAGTAATTT | 443 | 60 | 58 |

| s-Spy-R | AATGCCTTTAACTTCAGACTTAAAAA | ||||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae or S. mitis | s-Spn-F | CAATGTGGACTCAAAGATTATAGAAGAATG | 396 | 60 | 58 |

| s-Spn-R | GTCATGATACTAAGGCGCCCTA | ||||

| Streptococcus salivarius or S. thermophilus | s-Ssal-F | CAATGGATGACACATGTCATTTAT | 682 | 60 | This study |

| s-Ssal-R | GGCACTGAATCCCGGAAAGGATCC | ||||

| Lactococcus lactis subgroup | sg-Lclac-F | TGTAGGGAGCTATAAGTTCTCTGTA | 613 | 60 | This study |

| sg-Lclac-R | GGCAACCTACTTYGGGTACTCCC | ||||

| Lactococcus piscium subgroup | sg-Lcpis-F | GCTATCCAGCCCTAAGTGA | 614 | 60 | This study |

| sg-Lcpis-R | AAAGGTTAGCTCACCGGCTTTGGGTA |

Specific primer sets were developed using 16S rRNA gene sequences, except for primer sets sg-Eavi-F/R, s-Efm-F/R, g-Str-F/R, and s-Spn-F/R, which target the 23S rRNA gene.

The primer names reflect their target. The beginning of the primer name shows the taxon targeted (g, genus; sg, subgroup; s, species). The middle of the primer name shows the species (abbreviated). The end of the primer name shows whether it is a forward (F) or reverse (R) primer.

RNAs extracted from the standard strains described in Materials and Methods were used as RT-qPCR controls.

Determination of primer specificity.

The specificity of the primers used in this study was determined as follows. Total RNA fractions extracted from the bacterial cells of each strain shown in Table 1 at a dose corresponding to 1010 cells per 10 ml were assessed for RT-qPCR using the subgroup- or species-specific primers (Table 2). Bacterial cell counts were determined by the 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining method by the method of Jansen et al. (35). Each analytical curve ranging from 103 or 104 to 109 cells per 10 ml was generated with RT-qPCR data, threshold cycle (CT) value, and the corresponding cell count, which was determined microscopically with the DAPI staining method, of the dilution series of the following representative strains: E. faecalis ATCC 19433T (for g-Encoc-F/R and s-Efs-F/R), E. caccae DSM 19114T (for s-Ecacc-F/R), E. cecorum JCM 8724T (for s-Ececo-F/R), E. sulfureus DSM 6905T (for sg-Esulf-F/R), E. casseliflavus JCM 8723T (for sg-Ecass-F/R), E. avium JCM 8722T (for sg-Eavi-F/R), E. dispar DSM 6630T (for s-Edis-F/R), E. faecium ATCC 19434T (for sg-Efm-F/R and s-Efm-F/R), S. salivarius JCM 5707T (for g-Str-F/R and s-Ssal-F/R), S. mitis GIFU 12458T (for s-Spn-F/R), S. agalactiae JCM 5671T (for s-Sag-F/R), S. pyogenes ATCC 12344T (for s-Spy-F/R), L. lactis subsp. lactis ATCC 19435T (for sg-Lclac-F/R) and L. piscium DSM 6634T (for sg-Lcpis-F/R). Using the analytical curve, the amplified signal was judged positive when it was more than that of 109 standard cells and negative when it was less than that of 105 standard cells. Signals between 105 and 109 standard cells were defined as positive and negative. The amplified signal was defined as negative when the peak of the corresponding melting curve was different from that of the standard strain.

Total RNA isolation and RT-qPCR.

For RNA stabilization, each fresh bacterial culture (100 μl) was added to 2 volumes of RNAlater (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX). Although we had used RNAprotect bacterial reagent (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) to stabilize bacterial RNA in our previous method, we have changed it to RNAlater because of some advantages of using RNAlater, such as the longer stability, and have confirmed that the treatment of feces by RNAprotect and by RNAlater showed identical results. There were no significant differences in the results of RT-qPCR with the pure cultures of E. faecalis ATCC 19433T, S. salivarius JCM 5707T, and L. lactis subsp. lactis ATCC 19435T due to the difference in the RNA-stabilizing agents (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). After centrifugation of the mixture at 5,000 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was discarded, and pellets were stored at −80°C until used to extract RNA. RNA extraction and RT-qPCR were performed by the methods described by Matsuda et al. (43).

DNA extraction and qPCR.

DNA extraction and qPCR were performed by the methods described by Matsuki et al. (44). qPCR amplification and detection were performed in 384-well optical plates on an ABI PRISM 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems).

Collection and preparation of fecal samples.

A spoonful of feces (0.3 to 0.5 g) was collected into a tube containing 2 ml of RNAlater immediately after defecation. Each fecal sample was weighed and suspended in 9 volumes of RNAlater to make a fecal homogenate (100 mg feces/ml). In preparation for RNA extraction, 200 μl of the fecal homogenate was added to 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After centrifugation of the mixture at 5,000 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was stored at −80°C until used to extract RNA. In preparation for DNA extraction, 200 μl of the fecal homogenate was added to 1 ml of PBS, and after centrifugation of the mixture at 5,000 × g for 10 min, 1 ml of the supernatant was discarded. After another wash with 1 ml of PBS, the pellets were stored at −30°C until used to extract DNA.

Quantification of bacteria added to human feces by RT-qPCR and qPCR.

Fecal samples showing no response in a preliminary RT-qPCR assay with any of the five primer sets (s-Efs-F/R, s-Efm-F/R, sg-Lclac-F/R, sg-Lcpis-F/R, and s-Sag-F/R) were selected for the following spike experiment. Serial dilutions of E. faecalis ATCC 19433T, E. faecium ATCC 19434T, L. lactis subsp. lactis ATCC 19435T, L. piscium DSM 6634T, and S. agalactiae JCM 5671T were added to the fecal homogenate to obtain final concentrations ranging from 103 to 1010 cells per gram feces (per 10 ml fecal homogenates containing 1 g feces). As a reference, the same serial dilutions were added to MRS broth at final concentrations ranging from 103 to 1010 cells per 10 ml broth. The bacterial cell counts of the cultures spiked were enumerated by the DAPI staining method. Total RNA (about 40 μg) was extracted from the fecal homogenates, including 20 mg of the feces, and was dissolved in 1 ml of nuclease-free water. Similarly, DNA (about 30 μg) was extracted and dissolved in 1 ml of Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer. Five-microliter amounts of 100-fold dilutions of the nucleic acids (corresponding to 1/20,000 amounts of the extracted RNA and DNA [about 2 and 1.5 ng, respectively]) were subjected to RT-qPCR/qPCR analysis. CT values were obtained by RT-qPCR assay of RNA fractions extracted from the fecal homogenates and broth, with the specific primer sets: s-Efs-F/R, s-Efm-F/R, sg-Lclac-F/R, sg-Lcpis-F/R, and s-Sag-F/R (listed in Table 2). CT values were similarly obtained by qPCR assay of the DNA fractions extracted from the same fecal homogenates and broth. Each analytical curve was generated with a CT value and the corresponding cell count. Similarly, serial dilutions of E. dispar DSM 6630T were added to the fecal homogenates from five volunteers to obtain final concentrations ranging from 103 to 109 cells per gram feces, and RT-qPCR or qPCR analysis using the s-Edis-F/R primer set was performed.

Determination of bacterial count by RT-qPCR.

RNA fractions were extracted from fecal samples from 24 healthy adult volunteers (15 males and 9 females; ages, 20 to 65 years [average, 39 ± 13 years]) by a previously described method (43), and 1 ml of RNA solution extracted from 20 mg feces was obtained (RNA concentration, 33 ± 12 μg/ml). For identification of the target bacterial population in the fecal samples, 1/20,000, 1/200,000, or 1/2,000,000 portion of the extracted RNA from 20 mg of feces was subjected to RT-qPCR, and the CT values in the linear range of the assay were applied to the analytical curve generated in the same experiment to obtain the corresponding bacterial count in each nucleic acid sample, which was converted to the count per sample.

Sequencing of RT-PCR-amplified rRNA genes.

RT-PCR products generated with the primer sets of g-Encoc-F/R, g-Str-F/R, sg-Lclac-F/R, sg-Lcpis-F/R, and s-Sal-F/R were purified with Montage PCR centrifugal filter devices (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA) and used for sequence analysis of 16S or 23S rRNA gene fragments. Sequencing analysis was performed according to the method described by Matsuda et al. (43).

Determination of bacterial count by FISH.

FISH analyses were performed by the procedure of Takada et al. (65). Briefly, a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled oligonucleotide probe, Eub338 (5′-GCT GCC TCC CGT AGG AGT-3′) (1), was used to enumerate Gram-positive cocci. Each fresh culture of E. faecalis (ATCC 19433T, ATCC 6055, and ATCC 11700), S. salivarius (JCM 5707T, ATCC 9759, and ATCC 13419), or L. lactis subsp. lactis (ATCC 19435T, ATCC 11454, and ATCC 13675) was added to 3 volumes of a solution of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and PBS, which was then incubated at 4°C for 16 h. PFA-treated sample was smeared over a MAS-coated slide glass (Matsunami, Osaka, Japan), which was hybridized with the probes or stained with Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) after treatment with 1 mg/ml lysozyme (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) at 37°C for 15 min. Observation and acquisition of fluorescent images were performed with a Leica imaging system (an automatic fluorescent microscope Leica DM6000, image acquisition software QFluoro, and a cooled black-and-white charge-coupled device [CCD] camera Leica DFC3500FX) (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). The smear samples containing 30 to 300 targeted cells per field were prepared. The bacterial count was expressed as the mean value of 10 fields for each smear sample.

RESULTS

Primer specificity.

The specificity of the newly developed primers together with the Enterococcus genus-specific primers (43) and Streptococcus genus- or species-specific primers (58) (Table 2) was evaluated against the total RNA fractions extracted from 75 bacterial strains (shown in Table 1) corresponding to 1010 cells per 10 ml. Each primer set gave positive results only for its target bacterial subgroup or species. The primer sets of sg-Ecass-F/R (for the Enterococcus casseliflavus subgroup), sg-Eavi-F/R (for the E. avium subgroup), s-Edis-F/R (for E. dispar), g-Str-F/R (for the Streptococcus genus) and s-Spn-F/R (for Streptococcus pneumoniae or S. mitis) reacted with nontarget bacterial strains but approximately 10,000-fold less intensively than with the specific targets, indicating that these cross-reactions had little effect on specific enumeration of the target bacterial populations. The RNA fractions extracted from five strains of E. faecalis, three strains of S. salivarius, and five strains of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis were assessed by RT-qPCR using g-Encoc-F/R, g-Str-F/R, and sg-Lclac-F/R primer sets, indicating that quantification of the different strains was very precise (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Comparison of RT-qPCR, qPCR, and FISH for quantification of pure culture.

As for all primer sets used in this study, analytical curves generated by RT-qPCR and qPCR with 10-fold serial dilutions of RNA and DNA extracted from their target pure cultures were shown in Table 3. While the slope of the analytical curve obtained by RT-qPCR was almost equivalent to that of the corresponding curve by qPCR, there was a significant difference between the y-axis intercepts (CT values) for all the species tested, showing that the detection limits by RT-qPCR were at least 100 times lower than those by qPCR. The RT-qPCR method was also compared with FISH, a well-established methodology, for quantitative analysis of fresh pure culture of E. faecalis, S. salivarius, and L. lactis subsp. lactis (Table 4). The bacterial counts determined by RT-qPCR and FISH were found to be at equivalent levels, suggesting that the RT-qPCR method could enumerate target bacteria accurately.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of the detection limits by RT-qPCR and qPCR

| Speciesa | Primer set | RT-qPCR |

qPCR |

Δdet.b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical curve | Detection limit (log10 cells/g feces) | Analytical curve | Detection limit (log10 cells/g feces) | |||

| E. faecalis | g-Encoc-F/R | y = −3.39x + 46.3 | 3.0 | y = −3.38x + 52.4 | 6.0 | 3.0 |

| E. faecalis | s-Efs-F/R | y = −3.56x + 48.8 | 3.0 | y = −3.72x + 58.5 | 6.0 | 3.0 |

| E. caccae | s-Ecacc-F/R | y = −3.44x + 46.8 | 3.0 | y = −3.41x + 56.2 | 6.0 | 3.0 |

| E. cecorum | s-Ececo-F/R | y = −3.77x + 53.4 | 4.0 | y = −3.58x + 57.0 | 6.0 | 2.0 |

| E. sulfureus | sg-Esulf-F/R | y = −3.67x + 49.7 | 4.0 | y = −3.78x + 61.6 | 6.0 | 2.0 |

| E. casseliflavus | sg-Ecass-F/R | y = −3.52x + 45.8 | 3.0 | y = −3.62x + 55.3 | 6.0 | 3.0 |

| E. avium | sg-Eavi-F/R | y = −3.59x + 47.2 | 3.0 | y = −3.46x + 54.1 | 6.0 | 3.0 |

| E. dispar | s-Edis-F/R | y = −3.42x + 45.1 | 3.0 | y = −3.41x + 54.6 | 6.0 | 3.0 |

| E. faecium | sg-Efm-F/R | y = −3.62x + 51.0 | 4.0 | y = −3.65x + 60.5 | 6.0 | 2.0 |

| E. faecium | s-Efm-F/R | y = −3.50x + 48.7 | 4.0 | y = −3.58x + 58.5 | 6.0 | 2.0 |

| S. salivarius | g-Str-F/R | y = −3.87x + 50.0 | 4.0 | y = −3.74x + 58.9 | 6.0 | 2.0 |

| S. agalactiae | s-Sag-F/R | y = −4.92x + 61.6 | 4.0 | y = −4.71x + 70.0 | 7.0 | 3.0 |

| S. pyogenes | s-Spy-F/R | y = −3.69x + 53.9 | 4.0 | NTc | ||

| S. mitis | s-Spn-F/R | y = −3.63x + 53.2 | 4.0 | y = −3.74x + 60.1 | 6.0 | 2.0 |

| S. salivarius | s-Ssal-F/R | y = −3.81x + 53.4 | 4.0 | y = −3.91x + 61.4 | 7.0 | 3.0 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis | sg-Lclac-F/R | y = −3.55x + 51.0 | 4.0 | y = −3.50x + 59.4 | 6.0 | 2.0 |

| L. piscium | sg-Lcpis-F/R | y = −3.60x + 51.9 | 4.0 | y = −3.47x + 64.8 | 8.0 | 4.0 |

RNA/DNA fractions extracted from type strains of each species were supplied to RT-qPCR/qPCR to generate analytical curves.

The difference between the detection limits by RT-qPCR and qPCR (Δdet.) was calculated by subtracting the detection limit by RT-qPCR from that by qPCR.

NT, not tested.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of RT-qPCR and FISH for quantification of pure cultures

| Species | Strain | Log10 bacterial cells/ml culturea |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| RT-qPCRb | FISHc | ||

| E. faecalis | ATCC 19433T | 9.2 ± 0.1 | 9.1 ± 0.1 |

| ATCC 6055 | 9.1 ± 0.1 | 9.1 ± 0.1 | |

| ATCC 11700 | 8.9 ± 0.1 | 9.0 ± 0.1 | |

| S. salivarius | JCM 5707T | 8.9 ± 0.1 | 8.9 ± 0.1 |

| ATCC 9759 | 8.6 ± 0.1 | 8.8 ± 0.1 | |

| ATCC 13419 | 8.7 ± 0.1 | 8.6 ± 0.1 | |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis | ATCC 19435T | 9.1 ± 0.1 | 9.0 ± 0.1 |

| ATCC 11454 | 9.0 ± 0.2 | 9.0 ± 0.1 | |

| ATCC 13675 | 9.0 ± 0.1 | 8.9 ± 0.1 | |

The counts obtained by RT-qPCR and FISH are expressed as the number of log10 bacterial cells per milliliter of culture. The means ± standard deviations for the triplicate samples are expressed.

The counts were determined by RT-qPCR using g-Encoc-F/R, g-Str-F/R, and sg-Lclac-F/R primer sets.

The counts were determined by FISH using the Eub338 probe.

Comparison of RT-qPCR and qPCR for quantification of bacteria added to human feces.

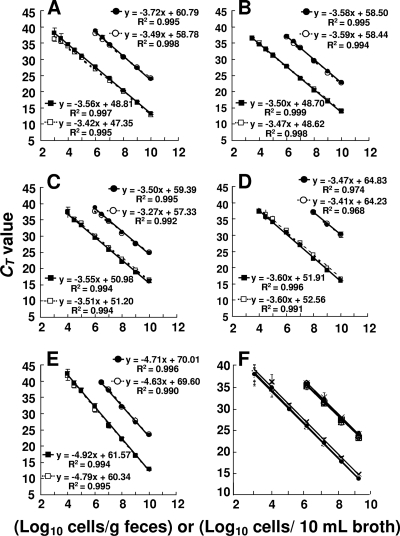

Serial dilutions of E. faecalis, E. faecium, L. lactis subsp. lactis, L. piscium, and S. agalactiae cell suspensions were added to the feces of volunteers who had been confirmed in advance not to have the corresponding indigenous populations and also added to the MRS broth as a reference. The counts of the added bacteria determined by the DAPI staining method (x axis) and the RT-qPCR value or the qPCR value (CT value, y axis) for E. faecalis, E. faecium, L. lactis subsp. lactis, and S. agalactiae were found to correlate well over the range of 103 to 1010 cells (R2, >0.99), while the correlation between the DAPI counts and the qPCR value for L. piscium was slightly low (R2, >0.96) (Fig. 1 A to E). With all 5 primer sets, the analytical curves for the counts in the feces corresponded with the equivalent counts in the broth, indicating that the bacteria added to the feces were accurately quantified by RT-qPCR. The amplification efficiencies of RT-qPCR and qPCR were also almost equal, judging from the slopes of their analytical curves. In contrast, there was a significant difference between the y-axis intercepts (CT values) of both analytical curves, namely, the detection limits, which were 103 to 104 bacterial cells per gram feces and were 100 to 10,000 times as sensitive as the qPCR assay (lower detection limits, 106 to 108 cells per gram feces). The E. dispar cells spiked into five different fecal specimens were quantified by the equivalent accuracy by RT-qPCR and qPCR using the s-Edis-F/R primer set (Fig. 1F).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the quantitative detection of bacteria added to human feces by RT-qPCR and by qPCR. (A to E) Fecal samples from a healthy adult supplemented with serial dilutions of E. faecalis ATCC 19433T (A), E. faecium ATCC 19434T (B), L. lactis subsp. lactis ATCC 19435T (C), L. piscium DSM 6634T (D), and S. agalactiae JCM 5671T (E) at final concentrations ranging from 103 to 1010 cells per gram were assessed by RT-qPCR (□) and qPCR (○) using primer sets s-Efs-R/R, s-Efm-F/R, sg-Lclac-F/R, sg-Lcpis-F/R, and s-Sag-F/R, respectively. As a reference, MRS broth supplemented with the same serial dilutions at final concentrations ranging from 103 to 1010 cells per 10 ml broth was also assessed by RT-qPCR (▪) and qPCR (•). (F) Fecal samples from five healthy adults spiked with E. dispar DSM 6630T at final concentrations ranging from 103 to 109 cells per gram were assessed by RT-qPCR and qPCR using the s-Edis-F/R primer set. Fecal samples from subject 1 (squares), 2 (diamonds), 3 (triangles), 4 (crosses) and 5 (circles) were examined by RT-qPCR (filled symbols) or qPCR (open symbols). The total bacterial count was determined by DAPI staining and plotted against the corresponding CT values obtained from RT-qPCR and qPCR assays.

Quantification of Gram-positive cocci in human feces by RT-qPCR.

RT-qPCR analysis was performed to enumerate Enterococcus, Streptococcus, and Lactococcus in the fecal samples collected from 24 healthy adult volunteers (15 males and 9 females; ages, 20 to 65 years [average, 39 ± 13 years]) (Table 5). The population levels of Enterococcus, Streptococcus, and Lactococcus were log10 6.2 ± 1.4, log10 7.5 ± 0.9, and log10 4.6 ± 1.2 (mean ± SD) cells per gram feces, respectively. Enterococcus and Streptococcus were detected in all 24 volunteers, while Lactococcus was detected in only 8 subjects (33%).

TABLE 5.

Quantification of human intestinal Gram-positive cocci in human feces by RT-qPCR

| Subjectb | Bacterial count (log10 cells/g feces)a |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total count with genus- and subgroup-specific primersc | Enterococcus with primer set g-Encoc-F/R | Streptococcus with primer set g-Str-F/R |

Lactococcusd |

|||

| Totale | With primer set sg-Lclac-F/R | With primer set sg-Lcpis-F/R | ||||

| 1 | 6.1 | 3.9 | 6.1 | ND | ND | ND |

| 2 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 6.4 | ND | ND | ND |

| 3 | 8.3 | 5.3 | 8.3 | ND | ND | ND |

| 4 | 7.8 | 7.1 | 7.7 | 3.1 | ND | 3.1 |

| 5 | 8.9 | 4.0 | 8.9 | ND | ND | ND |

| 6 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 6.8 | ND | ND | ND |

| 7 | 8.1 | 5.0 | 8.1 | 6.0 | 6.0 | ND |

| 8 | 8.5 | 6.2 | 8.5 | 5.2 | 5.2 | ND |

| 9 | 7.9 | 7.0 | 7.9 | ND | ND | ND |

| 10 | 8.2 | 6.0 | 8.2 | ND | ND | ND |

| 11 | 9.3 | 9.3 | 7.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 | ND |

| 12 | 7.0 | 6.6 | 6.8 | ND | ND | ND |

| 13 | 8.0 | 6.8 | 7.9 | 5.1 | 5.1 | ND |

| 14 | 6.4 | 6.3 | 5.9 | ND | ND | ND |

| 15 | 7.8 | 5.4 | 7.8 | ND | ND | ND |

| 16 | 8.4 | 8.3 | 7.8 | ND | ND | ND |

| 17 | 6.6 | 5.1 | 6.6 | ND | ND | ND |

| 18 | 7.4 | 5.3 | 7.4 | ND | ND | ND |

| 19 | 7.9 | 3.6 | 7.9 | ND | ND | ND |

| 20 | 9.1 | 7.2 | 9.1 | 5.3 | 5.3 | ND |

| 21 | 8.0 | 7.6 | 7.7 | ND | ND | ND |

| 22 | 7.5 | 6.5 | 7.4 | 5.3 | ND | 5.3 |

| 23 | 7.7 | 5.0 | 7.7 | 3.3 | ND | 3.3 |

| 24 | 6.1 | 5.5 | 5.9 | ND | ND | ND |

| Mean | 7.8 | 6.2 | 7.5 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 3.9 |

| SD | 0.9 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| Det. ratio (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 33 | 21 | 13 |

The counts obtained by RT-qPCR are expressed as the number of log10 bacterial cells.

Fecal samples were collected from 24 healthy Japanese adults (15 males and 9 females; ages, 20 to 65 years [average, 39 ± 13 years]). The means and standard deviations for the 24 subjects and the detection (Det.) ratios are expressed at the bottom of the table.

The total counts of bacteria are expressed as the sum of the counts determined by g-Encoc-F/R, g-Str-F/R, sg-Lclac-F/R, and sg-Lcpis-F/R primer sets.

ND, not detected.

The total counts of organisms belonging to Lactococcus species are expressed as the sum of the counts determined by sg-Lclac-F/R and sg-Lcpis- F/R primer sets.

To confirm the validity of quantification by RT-qPCR, sequence analysis of the RT-qPCR products was performed. The sequence analysis of the RT-qPCR products amplified by the g-Encoc-F/R primer set (0.30-kb fragments) revealed the presence of various bacteria belonging to enterococcal species, such as E. avium (GenBank accession no. AF133535), E. gilvus (GenBank accession no. DQ411810) or E. raffinosus (GenBank accession no. Y18296) or E. malodoratus (GenBank accession no. AJ301835), E. faecium (GenBank accession no. AJ301830) or E. durans (GenBank accession no. AJ276354), and E. faecalis (GenBank accession no. AB012212) in 9, 6, 6, and 3 of the 24 subjects tested, respectively, with identities of more than 99%. The values for homology between the sequences of the dominant 0.27-kb fragments amplified by the g-Str-F/R primer set and the 23S rRNA sequence of S. salivarius (GenBank accession no. ACLO01000090; region, 1 to 2878) or S. thermophilus (GenBank accession no. CP000419; region, 20970 to 23859) and S. bovis (GenBank accession no. AB168118) from 2 subjects (subjects 3 and 5) were 100% and 99.6%, respectively. The lactococcal species detected by sg-Lclac-F/R and sg-Lcpis-F/R primer sets (0.56-kb and 0.57-kb fragments, respectively) were found to be L. lactis subsp. lactis (GenBank accession no. AB100803) or L. lactis subsp. cremoris (GenBank accession no. AB100802), L. piscium (GenBank accession no. DQ343754), L. garvieae (GenBank accession no. AF061005), and L. plantarum (GenBank accession no. EF694029) with identity of more than 99%.

Composition of Enterococcus subgroups and Streptococcus subgroups by RT-qPCR.

RT-qPCR analysis using the subgroup- or species-specific primers was performed to investigate the population structure of various Enterococcus species in fecal samples from 24 subjects (Table 6). The mean total count of organisms belonging to Enterococcus species as the sum of four subgroups and four species was log10 5.9 ± 1.5 per gram feces, which showed a high correlation with the count determined by RT-qPCR using Enterococcus genus primers (log10 6.2 ± 1.4 per gram feces). The four major Enterococcus species subgroups, the E. avium subgroup, the E. faecium subgroup, E. faecalis, and the E. casseliflavus subgroup, were found to be widely distributed in adult intestines, with incidences of 79, 46, 46, and 33% and population levels of 5.4 ± 1.4, 5.9 ± 1.6, 5.2 ± 1.4, and 4.4 ± 1.0 (all values log10 mean ± SD per gram feces), respectively. E. caccae was detected in only one subject, and E. dispar, the E. sulfureus subgroup, and E. cecorum were not detected. The population level of E. faecium species was almost equal that of the E. faecium subgroup, except for one subject (subject 12). Considering that the sequence of the fragments amplified by the g-Encoc-F/R primer set in subject 12 was similar to the sequence of E. faecium or E. durans, the dominant enterococcal species was found to be E. durans. The E. avium subgroup, the E. faecium subgroup, and E. faecalis were the predominant enterococcal species of individual subjects, which was completely in agreement with the results of population levels determined by genus-specific primers and sequencing analysis.

TABLE 6.

Quantification of Enterococcus species subgroups in human feces by RT-qPCR

| Subjectb | Bacterial counts (log10 cells/g feces)a |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With primer set g-Encoc-F/R | Total count with species- and subgroup-specific primersc | With the following species- or subgroup-specific primer set: |

|||||||||

| sg-Eavi-F/R | sg-Efm-F/Rd | s-Efm-F/Re | s-Efs-F/R | sg-Ecass-F/R | s-Ecacc-F/R | s-Edis-F/R | sg-Esulf-F/R | s-Ececo-F/R | |||

| 1 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 3.4 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 2 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 6.9 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 3 | 5.3 | 4.8 | 3.9 | 4.8 | 4.9 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 4 | 7.1 | 6.8 | 6.8 | ND | 4.0 | 3.4 | 4.1 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 5 | 4.0 | 4.0 | ND | ND | ND | 4.0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 6 | 8.0 | 8.2 | 5.9 | 8.2 | 8.3 | 5.1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 7 | 5.0 | 5.0 | ND | ND | ND | 4.9 | 3.6 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 8 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 5.4 | 5.6 | ND | ND | 4.0 | ND | ND | ND |

| 9 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | ND | ND | 4.9 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 10 | 6.0 | 5.9 | ND | 5.8 | 6.0 | 4.1 | 3.4 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 11 | 9.3 | 9.5 | ND | 9.5 | 9.5 | 7.7 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 12 | 6.6 | 6.3 | 4.9 | 6.1 | ND | 5.8 | 4.8 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 13 | 6.8 | 6.2 | 6.0 | 5.4 | 5.5 | ND | 5.3 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 14 | 6.3 | 6.0 | ND | 6.0 | 6.2 | ND | 3.2 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 15 | 5.4 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 4.0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 16 | 8.3 | 7.8 | 7.8 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 17 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 4.6 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 18 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 4.9 | ND | ND | 4.2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 19 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 3.1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 20 | 7.2 | 7.4 | 3.1 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 7.4 | 5.3 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 21 | 7.6 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 5.4 | 5.4 | ND | 5.7 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 22 | 6.5 | 6.3 | 6.3 | ND | ND | 5.4 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 23 | 5.0 | 4.5 | 4.5 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 24 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 5.2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Mean | 6.2 | 5.9 | 5.4 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 5.2 | 4.4 | 4.0 | |||

| SD | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.0 | ||||

| Det. ratio (%) | 100 | 100 | 79 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 33 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The counts obtained by RT-qPCR are expressed as the number of log10 bacterial cells. ND, not detected.

Fecal samples were collected from 24 healthy Japanese adults (15 males and 9 females; ages, 20 to 65 years [average, 39 ± 13 years]). The means and standard deviations for the 24 subjects and the detection (Det.) ratios are expressed at the bottom of the table.

The total counts of organisms belonging to Enterococcus species are expressed as the sum of the counts determined by sg-Eavi-F/R, sg-Efm-F/R, s-Efs-F/R, sg-Ecass-F/R, s-Ecacc-F/R, s-Edis-F/R, sg-Esulf-F/R, and s-Ececo-F/R primer sets.

The counts are for E. faecium subgroup species (E. faecium, E. durans, E. mundtii, and E. hirae).

The counts are for E. faecium species.

Table 7 shows the diversity of the population levels of different Streptococcus species in the fecal samples. S. salivarius or S. thermophilus was detected in all the subjects at a mean population level of log10 7.4 (±0.8) per gram feces, which was equivalent to that determined by RT-qPCR using Streptococcus genus-specific primers (log10 7.5 ± 0.9 per gram feces). S. pneumoniae or S. mitis (100%) (log10 5.7 ± 0.8 per gram feces) and S. agalactiae (29%) (log10 4.9 ± 0.6 per gram feces) were detected with lower population levels, and S. pyogenes was not detected. These results suggest that S. salivarius or S. thermophilus is the predominant streptococcal species in Japanese adult intestines. Sequence analysis of RT-qPCR products amplified by the s-Ssal-F/R primer set (0.68-kb fragments) was performed to distinguish between these two species, which revealed that the species detected in all 24 subjects was S. salivarius.

TABLE 7.

Quantification of Streptococcus species in human feces by RT-qPCR

| Subjectb | Bacterial count (log10 cells/g feces)a |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With primer set g-Str-F/R | Total count with species-specific primersc | With the following species-specific primer set: |

||||

| s-Ssal-F/R | s-Spn-F/R | s-Sag-F/R | s-Spy-F/R | |||

| 1 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 5.4 | ND | ND |

| 2 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 4.9 | ND | ND |

| 3 | 8.3 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 6.3 | ND | ND |

| 4 | 7.7 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 5.4 | ND | ND |

| 5 | 8.9 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 5.7 | ND | ND |

| 6 | 6.8 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 5.3 | 4.3 | ND |

| 7 | 8.1 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 6.3 | 5.6 | ND |

| 8 | 8.5 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 7.1 | ND | ND |

| 9 | 7.9 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 5.8 | ND | ND |

| 10 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 6.6 | ND | ND |

| 11 | 7.2 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 5.3 | ND | ND |

| 12 | 6.8 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 4.6 | ND | ND |

| 13 | 7.9 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 4.8 | ND | ND |

| 14 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 4.8 | ND | ND |

| 15 | 7.8 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 5.6 | 4.1 | ND |

| 16 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 5.5 | ND | ND |

| 17 | 6.6 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 4.7 | 5.1 | ND |

| 18 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 5.9 | ND | ND |

| 19 | 7.9 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 5.4 | ND | ND |

| 20 | 9.1 | 8.8 | 8.8 | 7.6 | 5.5 | ND |

| 21 | 7.7 | 7.6 | 7.5 | 6.1 | ND | ND |

| 22 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 6.1 | ND | ND |

| 23 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 6.2 | 4.6 | ND |

| 24 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 4.9 | 4.8 | ND |

| Mean | 7.5 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 5.7 | 4.9 | |

| SD | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.6 | |

| Det. ratio (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 29 | 0 |

The counts obtained by RT-qPCR are expressed as the number of log10 bacterial cells. ND, not detected.

Fecal samples were collected from 24 healthy Japanese adults (15 males and 9 females; ages, 20 to 65 years [average, 39 ± 13 years]). The means and standard deviations for the 24 subjects and the detection (Det.) ratios are expressed at the bottom of the table.

The total counts of organisms belonging to Streptococcus species are expressed as the sum of the counts determined by s-Ssal-F/R, s-Spn-F/R, s-Sag-F/R, and s-Spy-F/R primer sets.

DISCUSSION

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) has been the most widely used molecular method in this field, and a variety of target genes, such as 16S rRNA, 23S rRNA, gtf, cpn60, and species-specific toxin genes, have been used for the detection of Enterococcus (3, 4, 13, 20, 33, 55), Streptococcus (19, 21, 26, 71), and Lactococcus (19, 25, 41). Although many studies have demonstrated the application of qPCR for analysis of fecal samples (3, 4, 13, 19, 20, 25, 41, 55), these quantitative detections were limited to several species or restricted to the range above 105 cells per gram feces, which is insufficient for the analysis of the subdominant populations that inhabit human intestines at such low population levels. In this study, for comprehensive quantification of the human intestinal Gram-positive cocci at both the genus subgroup and species levels, we have developed 16S or 23S rRNA-targeted primer sets for Enterococcus, Streptococcus, and Lactococcus. Each primer was designed against the highly conserved regions within each species by comparison of the sequences in silico, and the RNA fractions of several strains of E. faecalis, S. salivarius, and L. lactis subsp. lactis were assessed by RT-qPCR, revealing that each strain of the target species was equally quantified in accordance with the sequence analysis in silico (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Dividing the target species by the primer sets (e.g., species-specific or subgroup-specific primers) sometimes involved an inability to discriminate between certain species, which is related to the limitation of the method targeting the rRNA genes.

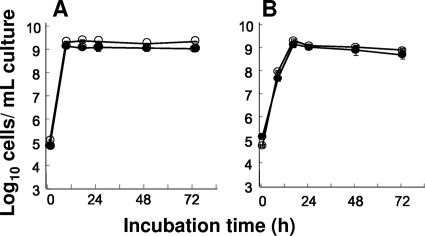

As our previous study suggested that the RT-qPCR method constitutes a breakthrough in terms of detection limits (42, 43), we confirmed that the RT-qPCR method with serial dilutions of RNA extracted from pure culture (Table 3) and with RNA fractions extracted from feces including target species (Fig. 1) was approximately 100 to 10,000 times as sensitive as the qPCR method. The higher detection limit of qPCR seems to be due to nonspecific amplification through the formation of primer dimers, which could delay the amplification cycle of qPCR. Both RNA and DNA were successfully extracted at the same levels regardless of the strains used, and the reason why the degree of difference between the detection limit by RT-qPCR and qPCR varies with the primer sets remains unclear. It is well-known that the expression of rRNA genes is tightly dependent on the physiological status of bacteria (24, 56), and we previously confirmed that the RT-qPCR method could accurately enumerate target organisms throughout the growth phase in broth culture (e.g., E. faecalis ATCC 19433T) (42). The cell counts determined by RT-qPCR and the culture method concerning E. faecium and L. lactis subsp. lactis were almost equivalent (Fig. 2), and the cell counts of pure cultures determined by RT-qPCR and FISH were also found to be at almost equal levels (Table 4), suggesting that RT-qPCR could be applied for accurate quantification of the Gram-positive cocci.

FIG. 2.

Effect of growth phase on bacterial counts determined by RT-qPCR. (A and B) Throughout the growth phase (0, 8, 16, 24, 48, and 72 h) in MRS broth culture, the numbers of E. faecium ATCC 19434T (A) and L. lactis subsp. lactis ATCC 19435T (B) cells were determined by RT-qPCR (○) and the culture method (•). The analytical curve of each standard strain was used to quantify the bacteria. The CFU counts were determined on MRS agar plates. The results are the means and standard deviations of triplicate samples.

As shown in Tables 6 and 7, the total counts of target organisms determined as the sum of the counts obtained by RT-qPCR using the subgroup- and species-specific primer sets and the counts by the genus-specific primer set were equivalent in most subjects, while there were some differences between the counts in several subjects, which may be because each genus-specific primer set targeted wide-ranging species belonging to the assigned genus, and therefore, the ranges of detection differed among species, although they were confirmed within a several fold range.

Many studies based on the conventional culture method have revealed that enterococci are a commensal intestinal population with an average count ranging from 105 to 107 CFU per gram feces and that E. faecalis is the species detected most frequently in fecal samples, followed by E. faecium and other less commonly found species, such as E. durans, E. avium, E. gallinarum, E. casseliflavus, and so on (5, 22, 23, 48, 50). Although recent molecular analyses have also revealed populations of enterococci, these were limited to the whole genus (55, 63) or to particular species, such as E. faecalis (3, 4) and E. faecium (20), and other species have not been examined effectively. Therefore, we believe that this is the first study to examine enterococcal populations in human intestines at both the species and subgroup levels and that this study reveals the true enterococcal diversity (Table 6). The RT-qPCR analysis provided new findings that the E. avium subgroup, including E. avium, E. raffinosus, E. malodoratus, E. gilvus, and E. pseudoavium, was the predominant enterococcal species subgroup in most of the healthy adults tested, followed by the E. faecium subgroup, E. faecalis, the E. casseliflavus subgroup, and E. caccae. Unlike well-characterized species, such as E. faecalis and E. faecium, which have been identified as being associated with several human diseases, such as infections (36, 48) and cancer (3, 67, 69), and antimicrobial resistance (47, 52), the species belonging to the E. avium subgroup are known to be relatively infrequently associated with human infections (48). Therefore, the fact that the E. avium subgroup is the most prevalent enterococcal group in human intestines may indicate that it plays an important role as a commensal intestinal inhabitant. The E. casseliflavus subgroup, the fourth most frequently detected species subgroup found in 33% of the subjects tested, includes E. casseliflavus, E. gallinarum, and E. flavescens, which have been recognized as important vancomycin-resistant enterococci (40, 49, 52). Considering the finding that the individuals harbored unique Enterococcus species, further analyses of enterococcal prevalence not only in healthy subjects as shown in this study but also in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., colon cancer, inflammatory bowel disease) are needed to identify possible relationships between enterococci and gastrointestinal symptoms.

As with enterococci, several streptococcal species have been found in human feces (18, 57), but comprehensive quantification has not been reported so far. In this study, RT-qPCR quantification and sequence analysis revealed that streptococci were detected in all the subjects at population levels of around 107 cells per gram feces, with the highest prevalence detected for S. salivarius, the dominant streptococcal species. Although it has been reported that S. salivarius is mainly found in the oral cavity (18, 32), our novel finding that S. salivarius is present at such a high level and high prevalence in human intestines suggests that S. salivarius is a commensal bacteria in human intestines. The RT-qPCR analysis using the s-Spn-F/R primer set also suggested that either S. pneumoniae or S. mitis colonizes human intestines, although these two species were indistinguishable because the 23S rRNA gene sequences of S. mitis (GenBank accession no. FN568063; region, 18468 to 21387) and S. pneumoniae (GenBank accession no. AB168128) are absolutely identical in the 0.36-kb fragments amplified by the s-Spn-F/R primer set. S. pneumoniae, which is the leading cause of community-acquired pneumonia (16, 46), has not been reported to colonize the human intestines, while S. mitis is a major component of oral microflora and is also found in human feces (16, 18). Taken together with the present findings, it therefore seems that the streptococcal species detected by the s-Spn-F/R primer set is S. mitis, but further studies are required to confirm this by targeting species-specific genes, such as pneumolysin (26). S. agalactiae, the most common cause of neonatal sepsis (62), is known to colonize the vaginas and recta of pregnant women (31). In our study, the number of subjects harboring S. agalactiae in feces accounted for 29% of the total, which was in agreement with the rates previously reported (14, 31, 34). S. pyogenes, which is a common pathogenic streptococcal species and causes not only common illnesses, such as pharyngitis, but also life-threatening diseases, such as sepsis and necrotizing fasciitis, was not found in the feces tested. Our results suggest that the species-specific primer sets used in this study covered most streptococcal species inhabiting human gastrointestinal tracts. On the other hand, a sequence analysis of the amplified DNAs revealed that the predominant species in only two subjects (subjects 3 and 5) was S. bovis, which was not covered by the subgroup- or species-specific primer sets in this study, indicating that the development of a S. bovis primer would lead to more comprehensive understanding of the population levels of Streptococcus in human intestines.

Although lactococci are found ubiquitously in the environment (e.g., in plants, animals, fish) and food (e.g., milk, cheeses, meats), only a few cases of their detection in fecal samples from adults have been reported (70). In this study, 4 lactococcal species were detected in 8 subjects (33%). L. lactis subsp. lactis or L. lactis subsp. cremoris has been widely used to produce dairy products (6, 10), and beneficial effects of this species on intestinal microbiota have been reported (37, 66). L. garvieae is known as an important species in aquaculture owing to its infections of fish (68), while there is little information with regard to L. piscium and L. plantarum. Considering our new finding that lactococci were detected in nearly one-third of the subjects and the accumulated information concerning the extent of lactococcal distribution in food and the environment, further studies are needed to ascertain whether lactococci are commensal or transient bacteria.

In conclusion, we developed a culture-independent quantification system for catalase-negative Gram-positive cocci in human intestines using rRNA-targeted RT-qPCR technology. RT-qPCR using the newly developed genus-, subgroup-, or species-specific primer sets enabled accurate and sensitive differentiation of the diverse bacterial groups that are otherwise frequently confused by existing identification systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Yukiko Kado for her assistance with this research.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 June 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann, R. I., B. J. Binder, R. J. Olson, S. W. Chisholm, R. Devereux, and D. A. Stahl. 1990. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1919-1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson, A. F., M. Lindberg, H. Jakobsson, F. Backhed, P. Nyren, and L. Engstrand. 2008. Comparative analysis of human gut microbiota by barcoded pyrosequencing. PLoS One 3:e2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balamurugan, R., E. Rajendiran, S. George, G. V. Samuel, and B. S. Ramakrishna. 2008. Real-time polymerase chain reaction quantification of specific butyrate-producing bacteria, Desulfovibrio and Enterococcus faecalis in the feces of patients with colorectal cancer. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 23:1298-1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartosch, S., A. Fite, G. T. Macfarlane, and M. E. McMurdo. 2004. Characterization of bacterial communities in feces from healthy elderly volunteers and hospitalized elderly patients by using real-time PCR and effects of antibiotic treatment on the fecal microbiota. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3575-3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benno, Y., K. Endo, T. Mizutani, Y. Namba, T. Komori, and T. Mitsuoka. 1989. Comparison of fecal microflora of elderly persons in rural and urban areas of Japan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:1100-1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beresford, T. P., N. A. Fitzsimons, N. L. Brennan, and T. M. Cogan. 2001. Recent advances in cheese microbiology. Int. Dairy J. 11:259-274. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosshard, P. P., S. Abels, M. Altwegg, E. C. Bottger, and R. Zbinden. 2004. Comparison of conventional and molecular methods for identification of aerobic catalase-negative gram-positive cocci in the clinical laboratory. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2065-2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casalta, E., and M. C. Montel. 2008. Safety assessment of dairy microorganisms: the Lactococcus genus. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 126:271-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claesson, M. J., O. O'Sullivan, Q. Wang, J. Nikkila, J. R. Marchesi, H. Smidt, W. M. de Vos, R. P. Ross, and P. W. O'Toole. 2009. Comparative analysis of pyrosequencing and a phylogenetic microarray for exploring microbial community structures in the human distal intestine. PLoS One 4:e6669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cogan, T. M., M. Barbosa, E. Beuvier, B. Bianchi-Salvadori, P. S. Cocconcelli, I. Fernandes, J. Gomez, R. Gomes, G. Kalantzopoulos, A. Ledda, M. Medina, M. C. Rea, and E. Rodriguez. 1997. Characterization of the lactic acid bacteria in artisanal dairy products. J. Dairy Res. 64:409-421. [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Bruin, M. A., and L. W. Riley. 2007. Does vancomycin prescribing intervention affect vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus infection and colonization in hospitals? A systematic review. BMC Infect. Dis. 7:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dethlefsen, L., S. Huse, M. L. Sogin, and D. A. Relman. 2008. The pervasive effects of an antibiotic on the human gut microbiota, as revealed by deep 16S rRNA sequencing. PLoS Biol. 6:e280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dumonceaux, T. J., J. E. Hill, S. A. Briggs, K. K. Amoako, S. M. Hemmingsen, and A. G. Van Kessel. 2006. Enumeration of specific bacterial populations in complex intestinal communities using quantitative PCR based on the chaperonin-60 target. J. Microbiol. Methods 64:46-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Easmon, C. S., A. Tanna, P. Munday, and S. Dawson. 1981. Group B streptococci-gastrointestinal organisms? J. Clin. Pathol. 34:921-923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emori, T. G., and R. P. Gaynes. 1993. An overview of nosocomial infections, including the role of the microbiology laboratory. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 6:428-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Facklam, R. 2002. What happened to the streptococci: overview of taxonomic and nomenclature changes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:613-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Facklam, R. R., and M. D. Collins. 1989. Identification of Enterococcus species isolated from human infections by a conventional test scheme. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:731-734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finegold, S. M., V. L. Sutter, P. T. Sugihara, H. A. Elder, S. M. Lehmann, and R. L. Phillips. 1977. Fecal microbial flora in Seventh Day Adventist populations and control subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 30:1781-1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Firmesse, O., E. Alvaro, A. Mogenet, J. L. Bresson, R. Lemee, P. Le Ruyet, C. Bonhomme, D. Lambert, C. Andrieux, J. Dore, G. Corthier, J. P. Furet, and L. Rigottier-Gois. 2008. Fate and effects of Camembert cheese micro-organisms in the human colonic microbiota of healthy volunteers after regular Camembert consumption. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 125:176-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Firmesse, O., S. Rabot, L. G. Bermudez-Humaran, G. Corthier, and J. P. Furet. 2007. Consumption of Camembert cheese stimulates commensal enterococci in healthy human intestinal microbiota. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 276:189-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furet, J. P., P. Quenee, and P. Tailliez. 2004. Molecular quantification of lactic acid bacteria in fermented milk products using real-time quantitative PCR. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 97:197-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gelsomino, R., M. Vancanneyt, T. M. Cogan, and J. Swings. 2003. Effect of raw-milk cheese consumption on the enterococcal flora of human feces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:312-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilmore, M. S., D. B. Clewell, P. Courvalin, G. M. Dunny, B. E. Murray, and L. B. Rice. 2002. The enterococci: pathogenesis, molecular biology, and antibiotic resistance. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 24.Gourse, R. L., T. Gaal, M. S. Bartlett, J. A. Appleman, and W. Ross. 1996. rRNA transcription and growth rate-dependent regulation of ribosome synthesis in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:645-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grattepanche, F., C. Lacroix, P. Audet, and G. Lapointe. 2005. Quantification by real-time PCR of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris in milk fermented by a mixed culture. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 66:414-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greiner, O., P. J. Day, P. P. Bosshard, F. Imeri, M. Altwegg, and D. Nadal. 2001. Quantitative detection of Streptococcus pneumoniae in nasopharyngeal secretions by real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3129-3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gueimonde, M., S. Tolkko, T. Korpimaki, and S. Salminen. 2004. New real-time quantitative PCR procedure for quantification of bifidobacteria in human fecal samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4165-4169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haarman, M., and J. Knol. 2006. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of fecal Lactobacillus species in infants receiving a prebiotic infant formula. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:2359-2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haarman, M., and J. Knol. 2005. Quantitative real-time PCR assays to identify and quantify fecal Bifidobacterium species in infants receiving a prebiotic infant formula. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:2318-2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamilton-Miller, J. M., and S. Shah. 1999. Identification of clinically isolated vancomycin-resistant enterococci: comparison of API and BBL Crystal systems. J. Med. Microbiol. 48:695-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hansen, S. M., N. Uldbjerg, M. Kilian, and U. B. Sorensen. 2004. Dynamics of Streptococcus agalactiae colonization in women during and after pregnancy and in their infants. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:83-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayashi, H., R. Takahashi, T. Nishi, M. Sakamoto, and Y. Benno. 2005. Molecular analysis of jejunal, ileal, caecal and recto-sigmoidal human colonic microbiota using 16S rRNA gene libraries and terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism. J. Med. Microbiol. 54:1093-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He, J. W., and S. Jiang. 2005. Quantification of enterococci and human adenoviruses in environmental samples by real-time PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:2250-2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Islam, A. K., and E. Thomas. 1980. Faecal carriage of group B streptococci. J. Clin. Pathol. 33:1006-1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jansen, G. J., A. C. Wildeboer-Veloo, R. H. Tonk, A. H. Franks, and G. W. Welling. 1999. Development and validation of an automated, microscopy-based method for enumeration of groups of intestinal bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 37:215-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jett, B. D., M. M. Huycke, and M. S. Gilmore. 1994. Virulence of enterococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 7:462-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kimoto-Nira, H., S. Ohmomo, M. Nomura, M. Kobayashi, K. Mizumahi, and T. Okamoto. 2008. Interference of in vitro and in vivo growth of several intestinal bacteria by Lactococcus strains. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 18:1286-1289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klijn, N., A. H. Weerkamp, and W. M. de Vos. 1995. Genetic marking of Lactococcus lactis shows its survival in the human gastrointestinal tract. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2771-2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knudtson, L. M., and P. A. Hartman. 1992. Routine procedures for isolation and identification of enterococci and fecal streptococci. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3027-3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leclercq, R., S. Dutka-Malen, J. Duval, and P. Courvalin. 1992. Vancomycin resistance gene vanC is specific to Enterococcus gallinarum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:2005-2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maruo, T., M. Sakamoto, T. Toda, and Y. Benno. 2006. Monitoring the cell number of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris FC in human feces by real-time PCR with strain-specific primers designed using the RAPD technique. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 110:69-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsuda, K., H. Tsuji, T. Asahara, Y. Kado, and K. Nomoto. 2007. Sensitive quantitative detection of commensal bacteria by rRNA-targeted reverse transcription-PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:32-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsuda, K., H. Tsuji, T. Asahara, K. Matsumoto, T. Takada, and K. Nomoto. 2009. Establishment of an analytical system for the human fecal microbiota, based on reverse transcription-quantitative PCR targeting of multicopy rRNA molecules. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:1961-1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsuki, T., K. Watanabe, J. Fujimoto, Y. Kado, T. Takada, K. Matsumoto, and R. Tanaka. 2004. Quantitative PCR with 16S rRNA-gene-targeted species-specific primers for analysis of human intestinal bifidobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:167-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuki, T., K. Watanabe, J. Fujimoto, T. Takada, and R. Tanaka. 2004. Use of 16S rRNA gene-targeted group-specific primers for real-time PCR analysis of predominant bacteria in human feces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:7220-7228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell, T. J. 2003. The pathogenesis of streptococcal infections: from tooth decay to meningitis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 1:219-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mundy, L. M., D. F. Sahm, and M. Gilmore. 2000. Relationships between enterococcal virulence and antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:513-522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murray, B. E. 1990. The life and times of the Enterococcus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 3:46-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Navarro, F., and P. Courvalin. 1994. Analysis of genes encoding D-alanine-D-alanine ligase-related enzymes in Enterococcus casseliflavus and Enterococcus flavescens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1788-1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noble, C. J. 1978. Carriage of group D streptococci in the human bowel. J. Clin. Pathol. 31:1182-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ogier, J. C., and P. Serror. 2008. Safety assessment of dairy microorganisms: the Enterococcus genus. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 126:291-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patel, R., J. R. Uhl, P. Kohner, M. K. Hopkins, and F. R. Cockerill III. 1997. Multiplex PCR detection of vanA, vanB, vanC-1, and vanC-2/3 genes in enterococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:703-707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poyart, C., G. Quesne, S. Coulon, P. Berche, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 1998. Identification of streptococci to species level by sequencing the gene encoding the manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:41-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rajilic-Stojanovic, M., H. G. Heilig, D. Molenaar, K. Kajander, A. Surakka, H. Smidt, and W. M. de Vos. 2009. Development and application of the human intestinal tract chip, a phylogenetic microarray: analysis of universally conserved phylotypes in the abundant microbiota of young and elderly adults. Environ. Microbiol. 11:1736-1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rinttila, T., A. Kassinen, E. Malinen, L. Krogius, and A. Palva. 2004. Development of an extensive set of 16S rDNA-targeted primers for quantification of pathogenic and indigenous bacteria in faecal samples by real-time PCR. J. Appl. Microbiol. 97:1166-1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruimy, R., V. Breittmayer, V. Boivin, and R. Christen. 1994. Assessment of the state of activity of bacterial cells by hybridization with a RNA targeted fluorescently labelled oligonucleotidic probe. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 15:207-214. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruoff, K. L., R. A. Whiley, and D. Beighton. 1998. Streptococcus, p. 283-296. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 58.Sakaguchi, S., M. Saito, H. Tsuji, T. Asahara, O. Takata, J. Fujimura, S. Nagata, K. Nomoto, and T. Shimizu. 2010. Bacterial ribosomal RNA-targeted reverse transcription PCR used to identify pathogens responsible for fever with neutropenia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1624-1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schleifer, K. H., and R. Kilpper-Bälz. 1987. Molecular and chemotaxonomic approaches to the classification of streptococci, enterococci and lactococci: a review. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 10:1-19. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schleifer, K. H., and R. Kilpper-Bälz. 1984. Transfer of Streptococcus faecalis and Streptococcus faecium to the genus Enterococcus nom. rev. as Enterococcus faecalis comb. nov. and Enterococcus faecium comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 34:31-34. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schleifer, K. H., J. Kraus, C. Dvorak, R. Kilpper-Bälz, M. D. Collins, and W. Fischer. 1985. Transfer of Streptococcus lactis and related streptococci to the genus Lactococcus gen. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 6:183-195. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schuchat, A. 1998. Epidemiology of group B streptococcal disease in the United States: shifting paradigms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:497-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sghir, A., G. Gramet, A. Suau, V. Rochet, P. Pochart, and J. Dore. 2000. Quantification of bacterial groups within human fecal flora by oligonucleotide probe hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2263-2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sood, S., M. Malhotra, B. K. Das, and A. Kapil. 2008. Enterococcal infections and antimicrobial resistance. Indian J. Med. Res. 128:111-121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takada, T., K. Matsumoto, and K. Nomoto. 2004. Development of multi-color FISH method for analysis of seven Bifidobacterium species in human feces. J. Microbiol. Methods 58:413-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Toda, T., H. Kosaka, M. Terai, H. Mori, Y. Benno, and Y. Yamori. 2005. Effects of fermented milk with Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris FC on defecation frequency and fecal microflora in healthy elderly volunteers. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Sci. Technol. 52:243-250. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vanhaecke, L., F. Vercruysse, N. Boon, W. Verstraete, I. Cleenwerck, M. De Wachter, P. De Vos, and T. van de Wiele. 2008. Isolation and characterization of human intestinal bacteria capable of transforming the dietary carcinogen 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:1469-1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vendrell, D., J. L. Balcazar, I. Ruiz-Zarzuela, I. de Blas, O. Girones, and J. L. Muzquiz. 2006. Lactococcus garvieae in fish: a review. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 29:177-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang, X., T. D. Allen, R. J. May, S. Lightfoot, C. W. Houchen, and M. M. Huycke. 2008. Enterococcus faecalis induces aneuploidy and tetraploidy in colonic epithelial cells through a bystander effect. Cancer Res. 68:9909-9917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Woodmansey, E. J., M. E. McMurdo, G. T. Macfarlane, and S. Macfarlane. 2004. Comparison of compositions and metabolic activities of fecal microbiotas in young adults and in antibiotic-treated and non-antibiotic-treated elderly subjects. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:6113-6122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yano, A., N. Kaneko, H. Ida, T. Yamaguchi, and N. Hanada. 2002. Real-time PCR for quantification of Streptococcus mutans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 217:23-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.