Abstract

The effects of nitrite and ammonium on cultivated methanotrophic bacteria were investigated. Methylomicrobium album ATCC 33003 outcompeted Methylocystis sp. strain ATCC 49242 in cultures with high nitrite levels, whereas cultures with high ammonium levels allowed Methylocystis sp. to compete more easily. M. album pure cultures and cocultures consumed nitrite and produced nitrous oxide, suggesting a connection between denitrification and nitrite tolerance.

The application of ammonium-based fertilizers has been shown to immediately reduce the uptake of methane in a number of diverse ecological systems (3, 5, 7, 8, 11-13, 16, 27, 28), due likely to competitive inhibition of methane monooxygenase enzymes by ammonia and production of nitrite (1). Longer-term inhibition of methane uptake by ammonium has been attributed to changes in methanotrophic community composition, often favoring activity and/or growth of type I Gammaproteobacteria methanotrophs (i.e., Gammaproteobacteria methane-oxidizing bacteria [gamma-MOB]) over type II Alphaproteobacteria methanotrophs (alpha-MOB) (19-23, 25, 26, 30). It has been argued previously that gamma-MOB likely thrive in the presence of high N loads because they rapidly assimilate N and synthesize ribosomes whereas alpha-MOB thrive best under conditions of N limitation and low oxygen levels (10, 21, 23).

Findings from studies with rice paddies indicate that N fertilization stimulates methane oxidation through ammonium acting as a nutrient, not as an inhibitor (2). Therefore, the actual effect of ammonium on growth and activity of methanotrophs depends largely on how much ammonia-N is used for assimilation versus cometabolism. Many methanotrophs can also oxidize ammonia into nitrite via hydroxylamine (24, 29). Nitrite was shown previously to inhibit methane consumption by cultivated methanotrophs and by organisms in soils through an uncharacterized mechanism (9, 17, 24), although nitrite inhibits purified formate dehydrogenase from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b (15). Together, the data from these studies show that ammonium and nitrite have significant effects on methanotroph activity and community composition and reveal the complexity of ammonia as both a nutrient and a competitive inhibitor. The present study demonstrates the differential influences of high ammonium or nitrite loads on the competitive fitness of a gamma-MOB versus an alpha-MOB strain.

Growth and activity of pure cultures.

Methylomicrobium album ATCC 33003 (a gamma-MOB strain) and Methylocystis sp. strain ATCC 49242 (an alpha-MOB strain) were grown in batch cultures (consisting of 100 ml of medium in 250-ml Wheaton bottles sealed with septated screw-top lids) with nitrate mineral salts medium (NMS; ATCC medium 1306) or ammonium mineral salts medium (AMS; ATCC medium 784) containing 10 μM copper at pH 6.8 under a 50% air-50% methane atmosphere. Cultures were initiated with 1 × 106 to 3 × 106 cells ml−1 and grown in the dark at 30°C with shaking (200 rpm). Although a range of NH4Cl (25 to 100 mM) and NaNO2 (0.5 to 5 mM) amendments were tested in both NMS and AMS (data not shown), 50 mM excess ammonium and 2.5 mM excess nitrite (the medium contained a 10 mM concentration of the respective N source) were selected for intensive investigation as these amounts caused differential responses by the bacteria but did not cause measurable osmotic effects. It must be recognized that bacteria in pure cultures have vastly different physiological responses from those operating in diverse natural communities; hence, while these N loads were necessary to stimulate measurable differential responses in the cultivated MOB, they are not directly applicable to MOB in natural environments.

M. album had shorter doubling times in AMS than in NMS (P = 0.03 by the t test), although final cell densities in the two media were equivalent as measured by direct microscopic counting using a Petroff-Hausser chamber under phase-contrast light microscopy (Table 1). Methylocystis sp. had equivalent doubling times and final cell densities when grown in NMS and AMS. Both strains released less nitrite when grown in AMS than in NMS, indicating more efficient uptake and assimilation of ammonium than nitrate as an N source (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Growth and activity measurements for pure cultures and cocultures of M. album and Methylocystis sp.a

| Organism(s) and medium formulation | Doubling time (h)b | Maximum cell no.c (108) | Rate of CH4 consumption (μmol·h−1)d | Amt (μmol) of N2O producede | Amt (μmol) of nitrite produced or consumede |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. album | |||||

| NMS | 5.01 (0.41) | 2.48 (0.28) | 25.87 (0.41) | 0.17 (0.17) | 22.94 (4.83) |

| NMS + NO2− | 3.90 (0.06/0.03) | 1.77 (0.20/0.05) | 25.60 (0.45) | 1.41 (0.42/0.03) | −55.32 (6.53/0.002) |

| NMS + NH4+ | 10.03 (2.67) | 1.28 (0.26/0.02) | 10.00 (6.01/0.04) | BDLf | 16.81 (3.44) |

| AMS | 3.94 (0.09) | 2.36 (0.35) | 23.20 (0.77) | 0.90 (0.65) | 7.19 (0.05) |

| AMS + NO2− | 3.68 (0.21) | 1.52 (0.08/0.04) | 22.14 (1.23) | 4.42 (0.29/0.0002) | −71.99 (10.64/0.01) |

| AMS + NH4+ | 7.01 (2.34) | 1.53 (0.15/0.05) | 20.13 (2.27) | BDL | 8.15 (0.96) |

| Methylocystis sp. | |||||

| NMS | 4.28 (0.39) | 4.81 (0.90) | 23.82 (0.18) | BDL | 18.55 (1.79) |

| NMS + NO2− | 12.40 (1.80/0.006) | 2.62 (0.58/0.05) | 10.54 (0.39/3.1E−06) | BDL | 108.60 (43.26/0.05) |

| NMS + NH4+ | 5.92 (0.02/0.007) | 3.88 (0.75) | 19.57 (0.51/0.0007) | BDL | 27.94 (11.58) |

| AMS | 4.57 (0.57) | 5.81 (0.90) | 20.81 (0.28) | BDL | 1.93 (0.80) |

| AMS + NO2− | 9.42 (0.84/0.004) | 2.14 (0.26/0.008) | 6.78 (1.12/0.0001) | BDL | 77.84 (28.14/0.03) |

| AMS + NH4+ | 6.61 (1.33) | 4.01 (0.12) | 19.94 (0.37) | BDL | 3.02 (0.91) |

| M. album and Methylocystis sp. | |||||

| NMS | 4.24 (0.30) | 3.58 (0.85) | 23.96 (0.38) | BDL | 0.011 (0.003) |

| NMS + NO2− | 6.71 (1.14/0.05) | 2.58 (0.31) | 23.82 (0.76) | 2.54 (0.52) | −0.17 (0.05/0.003) |

| NMS + NH4+ | 5.69 (0.34/0.02) | 2.98 (0.64) | 21.44 (0.57/0.01) | 0.99 (0.52) | 0.027 (0.11) |

| AMS | 4.16 (0.11) | 3.45 (0.67) | 22.80 (0.62) | 0.12 (0.12) | BDL |

| AMS + NO2− | 3.94 (0.33) | 2.89 (0.18) | 22.57 (0.59) | 4.14 (0.47/4.8E−06) | −0.54 (0.11) |

| AMS + NH4+ | 6.64 (1.00/0.03) | 3.16 (0.19) | 21.22 (0.72) | 0.24 (0.24) | 0.007 (0.002) |

Cultures were grown in NMS or AMS unamended or amended with nitrite (2.5 mM; 250 μmol for 100 ml of culture) or ammonium (50 mM; 5,000 μmol for 100 ml of culture). Boldface type indicates a significant difference for the parameter between experimental cultures with nitrite or ammonium amendment and control cultures without N amendment. Data for unamended cultures are underlined. The first number in parentheses represents the standard error for three replicated experiments, each with duplicate cultures (n = 6). The second number in parentheses is the P value from the two-sample t test for the experimental value and the control value for each significant parameter. P values were not determined when N2O was below the detection limit in either the control or the experimental cultures.

Doubling times were calculated over the interval from h 12 to 24 for all cultures (n = 6 for each treatment) except those of Methylocystis sp. in media with 2.5 mM nitrite, for which the interval from h 48 to 84 was used.

Average maximum number of cells in stationary phase counted after 60 h of growth, except for cultures of Methylocystis sp. in media with 2.5 mM nitrite, in which cells were counted after 96 h of growth. Initial numbers of cells: 1 × 106·ml−1 for M. album cultures, 3 × 106·ml−1 for Methylocystis sp. cultures, and 2 × 106·ml−1 for mixed cultures (with equivalent numbers of cells of the two species).

Linear rates of methane consumption were determined over the interval from h 12 to 48 for all cultures except those of Methylocystis sp. in media with nitrite amendment, for which the interval from h 12 to 84 was used. R2 values for regression lines ranged from 0.88 to 0.97 for M. album pure cultures and 0.93 to 0.97 for Methylocystis sp. pure cultures (except those in nitrite-amended NMS and AMS, for which values were 0.75 and 0.5, respectively) and 0.89 to 0.95 for cocultures.

Levels of N2O and nitrite were measured following 72 h of growth. Nitrite values indicate the net amount produced or consumed after subtraction of the 250 μmol from nitrite-amended samples.

BDL, below the detection limit.

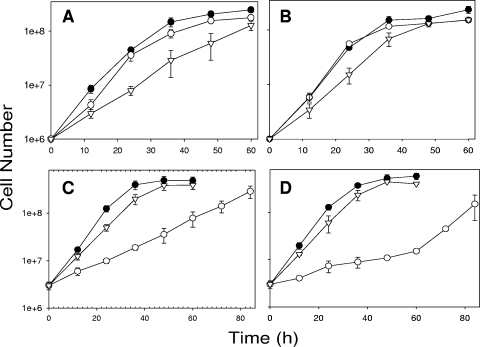

The addition of 2.5 mM nitrite decreased the initial doubling time for M. album in NMS but did not alter the overall growth curves (Fig. 1A and B) or methane consumption rates (Table 1) in either NMS or AMS as measured by gas chromatography (GC)-thermal conductivity detection (TCD) using a GC-8A instrument (Shimadzu) and a Hayesep Q column (Alltech). Final M. album cell densities were 29 and 36% lower in nitrite-amended than in unamended NMS and AMS, respectively (Table 1). Nitrite-amended cultures also showed net nitrite consumption (measured using a standard colorimetric assay [6]) and production of significantly more nitrous oxide (measured simultaneously with methane) than cultures with unamended medium. Amendment of Methylocystis sp. cultures with 2.5 mM nitrite significantly increased doubling times by 65 and 51%, increased methane consumption rates by 57 and 69%, and reduced final cell densities by 46 and 63% relative to those in unamended NMS and AMS, respectively (Table 1). Nitrite-amended cultures took 24 to 50 h longer to reach the end of exponential phase than unamended cultures (Fig. 1C and D). Unlike M. album cultures, Methylocystis sp. cultures accumulated nitrite in excess of the 2.5 mM amendment, and no nitrous oxide was detected in any Methylocystis sp. culture (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Growth curves for M. album in NMS (A) and AMS (B) and Methylocystis sp. in NMS (C) and AMS (D) without N amendment (•), with the addition of 2.5 mM NaNO2 (○), and with the addition of 50 mM NH4Cl (▿). Error bars represent standard errors for six replicate cultures as described in the text. Cells were enumerated by direct cell counting as described in the text.

The addition of 50 mM ammonium to M. album cultures increased doubling times, but not significantly, slowed methane consumption in NMS by 61%, and reduced final cell densities by 48 and 35% relative to those in unamended NMS and AMS, respectively (Table 1). Although similar amounts of nitrite were produced in ammonium-amended and unamended M. album cultures, no nitrous oxide was measured in ammonium-amended cultures. The addition of 50 mM ammonium to Methylocystis sp. cultures significantly increased doubling times and slowed methane consumption only in NMS, by 28 and 18%, respectively, and did not significantly alter final cell densities or nitrite production in any culture (Table 1; Fig. 1C and D).

Together, these results demonstrate that M. album was more tolerant to the inhibitory effects of nitrite than ammonium and that Methylocystis sp. was more tolerant to the inhibitory effects of ammonium than nitrite.

Growth and activity of cocultures.

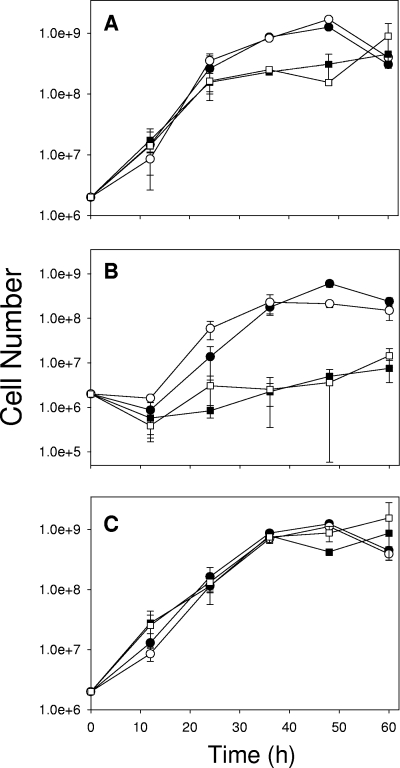

Cocultures with equivalent initial numbers of M. album and Methylocystis sp. cells were challenged with either 2.5 mM excess nitrite or 50 mM excess ammonium added to NMS or AMS. The cocultures grew equally well in the two types of unamended media, consumed methane at similar rates, and reached similar final cell densities (Table 1). Enumeration of cells of the two isolates by quantitative PCR (qPCR) showed equivalent numbers in the cocultures from 0 to 24 h, at which point M. album outgrew Methylocystis sp., accounting for 80 to 90% of the population by 48 h (Fig. 2A). However, late into the period of zero net cell growth (60 h), the percentage of M. album cells decreased to 31 to 41% of the population while Methylocystis sp. became dominant. Interestingly, nitrite levels did not substantially increase in NMS or AMS cocultures and N2O levels were lower than those in pure cultures of M. album, indicating more efficient N assimilation by the coculture than by either pure culture (Table 1).

FIG. 2.

Individual growth curves for M. album (•, ○) and Methylocystis sp. (▪, □) in cocultures. Cells of the two isolates were enumerated separately by qPCR. Cocultures were grown in NMS (closed symbols) or AMS (open symbols) without N amendment (A), with the addition of 2.5 mM NaNO2 (B), or with the addition of 50 mM NH4Cl (C). Standard errors for replicated experiments (n = 6) are indicated by bars. R2 values and PCR efficiency for standard curves with known cell numbers were 0.99 and 107% for M. album and 0.94 and 137% for Methylocystis sp.

For qPCR, primers were designed for M. album (Ma455F1, TCTGATGGCGAATACCCATC, and Ma856R, CACGAATCTTACGAATAAG) and Methylocystis sp. (Mcy177F1, GGATACGTGCGAGAGCAGA, and Mcy481R1, CCGTCATTATCGTCCCTGGC) by aligning their 16S rRNA genes using ClustalX (14). Primer sets were tested against both strains to ensure specificity. Standard curves were based on a dilution series of 102 to 108 cell ml−1 for each bacterium and verified by direct cell counting. Total DNA was extracted with a one-step, closed-tube cell lysis and DNA extraction system (ZyGem, New Zealand) with 100% efficiency. qPCRs (with 30-μl reaction mixtures) were performed using a MyIQ optical thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with one primer set at a time and with standard reagent concentrations for Taq polymerase, as follows: 95°C for 5 min and 45 cycles at 94°C (10 s), 60°C (20 s), 72°C (20 s), and 85°C (10 s) to measure the fluorescence from Sybr green I (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) while avoiding signals from primer-dimer pairs. Threshold cycle (CT) values from the standards were used to extrapolate relative cell numbers in the samples.

The addition of 2.5 mM nitrite to the cocultures resulted in essentially no growth of Methylocystis sp. until well into the period of zero net change in cell numbers; 98 to 99% of growth through exponential phase was attributable to M. album, which also accounted for 94 to 97% of the population after 60 h of growth (Fig. 2B). Methane oxidation rates and final cell densities were unaffected by the addition of nitrite relative to those in unamended cocultures (Table 1). Doubling times increased only in NMS, by 37% relative to those in unamended cocultures. Levels of N2O production in nitrite-amended cocultures were similar to that in nitrite-amended M. album pure cultures (Table 1).

Ammonium-amended cocultures showed equivalent growth of the two bacteria up to late log phase (36 h), at which point loss of M. album cells and growth of Methylocystis sp. resulted in dominance of the latter after 60 h (Fig. 2C). Addition of ammonium increased doubling times for the coculture by 25 and 37% relative to those for unamended NMS and AMS cocultures, respectively (Table 1). Ammonium amendment had no effect on final cell densities in either medium or on methane oxidation rates in AMS, but methane oxidation rates in NMS decreased by 11% relative to those in unamended cocultures. A small amount of nitrous oxide was detected in ammonium-amended cocultures, although far less nitrite was released into the media than in ammonium-amended pure cultures of either bacterium (Table 1).

Results from the cocultures indicate that M. album outcompeted Methylocystis sp. in the absence of challenge by high N loads (i.e., in unamended cocultures) and in the presence of high nitrite levels and that ammonium-amended cocultures provided greater competitive fitness to Methylocystis sp. Findings from prior studies indicate that Methylocystis isolates prefer low methane concentrations (18) or low oxygen concentrations (4), which may explain the resurgence of Methylocystis sp. following exponential cell growth.

Conclusions.

It is clear that ammonium and nitrite have strong effects on methanotrophic activity and, in ecological studies, on community composition. The present study demonstrates that competitive fitness of individual methanotrophic strains depends upon differential mechanisms to overcome inhibition and toxicity from imposed high N loads, as well as an ability to rapidly respond to and assimilate available nutrients. Consumption of nitrite and production of N2O by M. album suggest that denitrifying ability may be an important mechanism for its relatively high tolerance of nitrite.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Kearney Foundation of Soil Science grant no. 2005.202 to L. Y. Stein.

We thank B. D. Lanoil and anonymous reviewers for critical reading and comments.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 July 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bédard, C., and R. Knowles. 1989. Physiology, biochemistry, and specific inhibitors of CH4, NH4+, and CO oxidation by methanotrophs and nitrifiers. Microbiol. Rev. 53:68-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodelier, P. L. E., P. Roslev, T. Henckel, and P. Frenzel. 2000. Stimulation by ammonium-based fertilizers of methane oxidation in soil around rice roots. Nature 403:421-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosse, U., P. Frenzel, and R. Conrad. 1993. Inhibition of methane oxidation by ammonium in the surface layer of a littoral sediment. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 13:123-134. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowman, J. 2006. The methanotrophs—the families Methylococcaceae and Methylocystaceae, p. 266-289. In M. Dworkin et al. (ed.), The prokaryotes, vol. 5. Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bronson, K. F., and A. R. Mosier. 1994. Suppression of methane oxidation in aerobic soil by nitrogen fertilisers, nitrification inhibitors, and urease inhibitors. Biol. Fertil. Soils 17:263-268. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clesceri, L. S., A. E. Greenberg, and A. D. Eaton (ed.). 1998. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 20th ed. American Public Health Association, Washington, DC.

- 7.Conrad, R., and F. Rothfuss. 1991. Methane oxidation in the soil surface layer of a flooded rice field and the effect of ammonium. Biol. Fertil. Soils 12:28-32. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crill, P. M., P. J. Martikainen, H. Nykanen, and J. Silvola. 1994. Temperature and N fertilization effects on methane oxidation in a drained peatland soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 26:1331-1339. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunfield, P. F., and R. Knowles. 1995. Kinetics of inhibition of methane oxidation by nitrate, nitrite, and ammonium in a humisol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3129-3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graham, D. W., J. A. Chaudhary, R. S. Hanson, and R. G. Arnold. 1993. Factors affecting competition between type I and type II methanotrophs in two-organism, continuous-flow reactors. Microb. Ecol. 25:1-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen, S., J. E. Maehlum, and L. R. Bakken. 1993. N2O and CH4 fluxes in soil influenced by fertilization and tractor traffic. Soil Biol. Biochem. 25:621-630. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hütsch, B. W. 1998. Methane oxidation in arable soil as inhibited by ammonium, nitrite, and organic manure with respect to soil pH. Biol. Fertil. Soils 28:27-35. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hütsch, B. W. 1996. Methane oxidation in soils of two long-term fertilization experiments in Germany. Soil Biol. Biochem. 28:773-782. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeanmougin, F., J. D. Thompson, M. Gouy, D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1998. Multiple sequence alignment with Clustal X. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23:403-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jollie, D. R., and J. D. Lipscomb. 1991. Formate dehydrogenase from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b—purification and spectroscopic characterization of the cofactors. J. Biol. Chem. 266:21853-21863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kightley, D., D. B. Nedwell, and M. Cooper. 1995. Capacity for methane oxidation in landfill cover soils measured in laboratory-scale soil microcosms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:592-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King, G. M., and S. Schnell. 1994. Ammonium and nitrite inhibition of methane oxidation by Methylobacter albus BG8 and Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b at low methane concentrations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:3508-3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knief, C., and P. F. Dunfield. 2005. Response and adaptation of different methanotrophic bacteria to low methane mixing ratios. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1307-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee, S. W., J. Im, A. A. DiSpirito, L. Bodrossy, M. J. Barcelona, and J. D. Semrau. 2009. Effect of nutrient and selective inhibitor amendments on methane oxidation, nitrous oxide production, and key gene presence and expression in landfill cover soils: characterization of the role of methanotrophs, nitrifiers, and denitrifiers. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85:389-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacDonald, J. A., U. Skiba, L. J. Sheppard, K. J. Hargreaves, K. A. Smith, and D. Fowler. 1996. Soil environmental variables affecting the flux of methane from a range of forest, moorland, and agricultural soils. Biogeochemistry 34:113-132. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohanty, S. R., P. L. E. Bodelier, V. Floris, and R. Conrad. 2006. Differential effects of nitrogenous fertilizers on methane-consuming microbes in rice field and forest soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:1346-1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mosier, A. R., D. S. Schimel, D. W. Valentine, K. Bronson, and W. J. Parton. 1991. Methane and nitrous oxide fluxes in native, fertilized and cultivated grasslands. Nature 350:330-332. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noll, M., P. Frenzel, and R. Conrad. 2008. Selective stimulation of type I methanotrophs in a rice paddy soil by urea fertilization revealed by RNA-based stable isotope probing. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 65:125-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nyerges, G., and L. Y. Stein. 2009. Ammonia co-metabolism and product inhibition vary considerably among species of methanotrophic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 297:131-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiu, Q. F., M. Noll, W. R. Abraham, Y. H. Lu, and R. Conrad. 2008. Applying stable isotope probing of phospholipid fatty acids and rRNA in a Chinese rice field to study activity and composition of the methanotrophic bacterial communities in situ. ISME J. 2:602-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saari, A., P. J. Martikainen, A. Ferm, J. Ruuskanen, W. DeBoer, S. R. Troelstra, and H. J. Laanbroek. 1997. Methane oxidation in soil profiles of Dutch and Finnish coniferous forests with different texture and atmospheric nitrogen deposition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 29:1625-1632. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steudler, P. A., R. D. Bowden, J. M. Melillo, and J. D. Aber. 1989. Influence of nitrogen fertilizer on methane uptake in temperate forest soils. Nature 341:314-316. [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Nat, F.-J. W. A., J. F. C. de Brouwer, J. J. Middelburg, and H. J. Laanbroek. 1997. Spatial distribution and inhibition by ammonium of methane oxidation in intertidal freshwater marshes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4734-4740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whittenbury, R., K. C. Phillips, and J. F. Wilkinson. 1970. Enrichment, isolation and some properties of methane-utilizing bacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 61:205-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu, L. Q., K. Ma, and Y. H. Lu. 2009. Rice roots select for type I methanotrophs in rice field soil. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 32:421-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]