Abstract

West Nile virus (WNV) infection leads to rapid and sustained Ca2+ influx. This influx was observed with different strains of WNV and in different types of cells. Entry during virion endocytosis as well as through calcium channels contributed to the Ca2+ influx observed in WNV-infected cells. Ca2+ influx was not detected after infection with vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) and occurred only through endocytosis in Sindbis virus-infected cells. Caspase 3 cleavage and activation of several kinases, including focal adhesion kinase (FAK), mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK1/2), and protein-serine kinase B alpha (Akt), at early times after WNV infection were shown to be dependent on Ca2+ influx. Although the activation of these kinases was sustained in virus-infected cells throughout infection, UV-inactivated WNV induced only a transient activation of FAK and ERK1/2 at early times after infection. The Ca2+-dependent FAK activation observed in WNV-infected cells was not mediated by αvβ3 integrins. Reduction of Ca2+ influx at early times of infection by various treatments decreased the viral yield and delayed both the early transient caspase 3 cleavage and the activation of FAK, Akt, and ERK signaling. The results indicate that Ca2+ influx is required for early infection events needed for efficient viral replication, possibly for virus-induced rearrangement of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane. Increased caspase 3 cleavage at both early (transient) and late times of infection correlated with decreased activation of the FAK and ERK1/2 pathways, indicating a role for these kinases in extending the survival of flavivirus-infected cells.

Ca2+ regulates both rapid cell processes, such as cytoskeleton remodeling and the release of vesicle contents, and slower ones, including transcription, proliferation, contraction, exocytosis, and apoptosis, either directly after entering the plasma membrane through Ca2+ channels or indirectly, as a second messenger after release from an intracellular store (5, 7, 10, 55). Extracellular concentrations of Ca2+ are typically four times higher than intracellular levels. An increase in intracellular Ca2+ was previously reported to occur during endocytosis-mediated entry of several enveloped viruses. For instance, a transient increase in intracellular Ca2+ and transient activation of Ca2+ signaling pathways, such as tyrosine phosphorylation of the nonreceptor kinase Pyk2, were previously reported to result from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) envelope glycoprotein binding to a chemokine receptor (3, 14, 28). Human cytomegalovirus (21) and herpes simplex virus (11) activate Ca2+ signaling that plays a critical role during the entry of these viruses. Alterations in cell Ca2+ homeostasis have also been reported during viral infections, including hepatitis C virus, rotaviruses, hepatitis B virus, cytomegalovirus, enteroviruses, and others (10, 55).

Although flaviviruses are known to enter cells by endocytosis (12), little is known about signaling events triggered by flavivirus infections or about the involvement of Ca2+. The finding in a previous study that focal adhesion kinase (FAK) was activated by West Nile virus (WNV) infection led the authors to speculate that FAK was a receptor for WNV and that FAK activation resulted from its interaction with virions (13). However, a subsequent study showed that cells lacking expression of FAK were efficiently infected by WNV, which ruled out a requirement of FAK as a receptor for WNV (32). FAK has previously been reported to be activated by Ca2+ (44).

The involvement of Ca2+ in FAK activation during WNV infection and the effect of infection on Ca2+ homeostasis were analyzed in the present study. Rapid Ca2+ influx through endocytosis as well as through ion channels was observed after infection of several types of cells with different strains of WNV. Ca2+ influx triggered early transient caspase 3 cleavage as well as activation of several kinases, including FAK, protein-serine kinase B alpha (Akt), and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2), in WNV-infected cells. Although UV-inactivated WNV induced early activation of FAK and ERK1/2, sustained activation of these kinases required replication-competent virus. Reduction of Ca2+ influx at early times of infection by various treatments decreased the viral yield and delayed the early transient caspase 3 cleavage and the activation of FAK, Akt, and ERK signaling. The results show that Ca2+ is required for early infection events that are essential for efficient viral replication. Decreased activation of FAK and ERK1/2 during infection with WNV correlated with increased caspase 3 cleavage, indicating the role of these kinases in the survival of infected cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inhibitors and Ca2+ chelators.

Verapamil, nifedipine, diltiazem, EGTA, and the peptide caspase 3 inhibitor DEVD-CHO were purchased from Calbiochem and diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) ethanol or phosphate-buffered saline according to the manufacturer's instructions. The non-cell-permeating Ca2+ chelator 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA) and the cell-permeating cytosolic acetoxymethyl ester form of BAPTA (BAPTA-AM), as well as 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) and U0126, were purchased from Sigma.

Cell lines and viruses.

Primary C3H/He mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) and simian virus 40 (SV40)-transformed C3H/He and C57BL/6 MEF lines, as well as BHK-21 WI2 cells, were maintained as previously described (42). CS-1 hamster melanoma cells were grown in suspension in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 5% fetal bovine serum and 1% gentamicin. A stock of the Eg101 strain of WNV (lineage 1) was prepared by infecting BHK cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 and harvesting culture fluid 32 h after infection. Clarified culture fluid (108 PFU/ml) was aliquoted and stored at −80°C. To prepare a calcium-free virus stock, stock virus was pelleted by ultracentrifugation for 2 h at 80,000 × g and then resuspended in calcium-free medium (Invitrogen). A stock of WNV W956 (lineage 2) was produced by transfecting BHK cells with 1 μg of RNA transcribed in vitro from plasmid pSP6WNrep/Xba DNA (54) and harvesting the culture fluid 72 h after transfection. Clarified culture fluid (107 PFU/ml) was aliquoted and stored at −80°C. A vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) strain New Jersey stock was prepared by infecting BHK cells at an MOI of 1 and harvesting the culture fluid 9 h after infection (109 PFU/ml). A Sindbis virus stock of strain SAAR 339 (7 × 109 PFU/ml) was prepared as a 10% (wt/vol) newborn mouse brain homogenate. Plaque assays to measure virus infectivity were done in BHK cells as previously described (42).

Preparation of UV-inactivated WNV.

WNV strain Eg101 (108 PFU/ml; 200 μl/tube) was inactivated by exposure to UV light (4.75 J/cm2) for 10 min at a distance of 10 cm. The complete loss of detectable infectivity after UV exposure was confirmed by plaque assay.

MTT assay.

A colorimetric tetrazolium salt thiazolyl blue (MTT)-based assay (CellTiter 96 nonradioactive cell proliferation assay; Promega), performed according to the manufacturer's instructions, was used to assess cell viability. Cells were incubated with the dye solution for 1 h at 37°C, and then solubilization/stop solution was added. The quantification of live cells was assayed by measuring the specific absorbance at 570 nm, using a Victor 3 1420 multilabel plate reader (Perkin Elmer).

Calcium measurements.

Changes in the intracellular cytosolic Ca2+ concentration were measured with the calcium-sensitive dye Fluo-4NW (Fluo-4NW calcium assay kit; Molecular Probes) in a Victor 3 1420 multilabel plate reader (Perkin Elmer). Briefly, C3H/He MEFs or BHK cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 10,000 cells/well. The next day, the confluent monolayers were washed twice with Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) and loaded with 100 μl of Fluo-4NW dye mix according to the manufacturer's protocol. The cells were then incubated with either culture medium, WNV at an MOI of 5, or UV-inactivated virus at a concentration equivalent to an MOI of 5. The Fluo-4NW dye in the cells was excited at a wavelength of 494 nm, and fluorescence emission was measured at 516 nm. Recordings were collected from each well at 5-min intervals over a 2-h period.

Kinex antibody microarray.

Confluent monolayers of second-passage primary C3H/He MEFs were either mock infected or infected with WNV Eg101 at an MOI of 5 for 1 h. Cell lysates were then prepared using Kinexus (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7; 2 mM EGTA; 5 mM EDTA; 30 mM sodium fluoride; 40 mM glycerophosphate; 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate; 2 mM sodium orthovanadate; 10 μM leupeptin; 5 μM pepstatin A; 0.5% Triton X-100; and Complete Mini protease inhibitor cocktail tablets [Roche]). The cells were sonicated twice for 15 s each time. The homogenates were then subjected to ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 30 min in a Beckman TL-100 tabletop ultracentrifuge. The lysates were diluted in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer and sent to Kinexus for Kinetworks phosphosite screen 1.3 analysis of 31 phosphoprotein phosphorylation sites. Densitometry of the protein bands was used to calculate the n-fold change in phosphoprotein levels in WNV-infected cells compared to mock-infected cells.

Western blotting.

Western blotting was carried out as described previously (43). The membranes were incubated with polyclonal primary antibodies specific for p-Tyr (pY350; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), actin (Abcam), phospho-FAK (Tyr397) (Invitrogen), phospho-FAK (Tyr576/577), FAK, phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), ERK1/2, phospho-Akt (Ser473), phospho-protein kinase C (phospho-PKC) alpha/beta (Thr638/641), PKC alpha, caspase 3, and caspase 3 cleavage (Cell Signaling). Mouse monoclonal anti-NS5 antibody (270) was kindly provided by Pei-Yong Shi.

RESULTS

Analysis of the effects of extracellular Ca2+ chelators on virus yield.

To determine whether reduced levels of extracellular Ca2+ affected the efficiency of WNV production, the titer of extracellular virus was analyzed at different times after infection on cells cultured in medium containing BAPTA or EGTA. Confluent MEF monolayers were pretreated for 2 h with an extracellular Ca2+ chelator (50 μM BAPTA or 0.5 mM EGTA). The chelator concentrations used were the same as those previously reported to reduce the entry of extracellular Ca2+ into mammalian cells maintained in DMEM or a similar medium (6, 11). Cells were then mock infected or infected with WNV Eg101 at an MOI of 5 for 1 h in the presence of the same concentration of drug. The monolayers were washed to remove unadsorbed virus and then incubated with medium containing no drug or drug for an additional 2 or 20 h, followed by replacement with fresh medium. Virus infectivity in samples of culture fluid collected at the indicated times was determined by plaque assay on BHK cells (Fig. 1 A). Pretreatment of cells with BAPTA for 2 h before WNV infection and during adsorption for 1 h had no effect on virus yield at 20 h (Fig. 1A), indicating that virus entry was not affected by BAPTA treatment. However, continuation of the treatment of cells with BAPTA after virus adsorption reduced the viral yield about 50-fold (2 h of treatment) or 100-fold (20 h of treatment) compared to the yield from vehicle-treated, control-infected cells. Incubation of cells for 20 h after infection with 0.5 mM EGTA (a less potent Ca2+ chelator) reduced the WNV yield 10-fold at 24 h (data not shown).

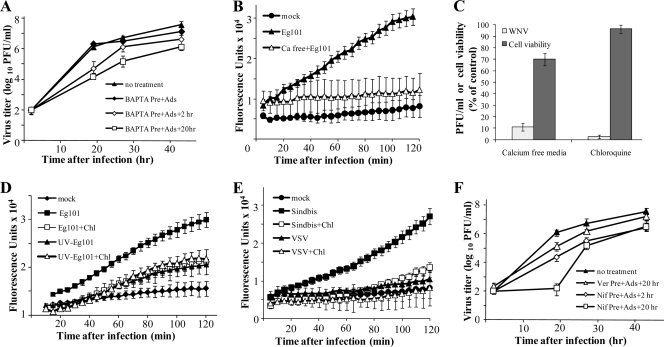

FIG. 1.

WNV infection induces an extracellular Ca2+ influx that enhances virus production. Confluent monolayers of C3H/He MEFs were pretreated with 50 μM BAPTA (A), preincubated in a calcium-free medium (B), or treated with 20 μM chloroquine (D) or 50 μM nifedipine (F) for 2 h. The cells were then mock infected or infected with WNV at an MOI of 5 for 1 h in the presence of drug and were maintained thereafter in medium with drug (or calcium-free medium) for either 2 or 20 h after infection, followed by replacement with fresh medium. Samples of culture fluid were harvested at the indicated times, and titers were determined by plaque assay on BHK cells. Error bars indicate ± standard deviations (SD) (n = 3). (C) The viability of chloroquine-treated MEFs or cells maintained in calcium-free medium was determined by MTT assay as described in Materials and Methods. Extracellular virus titers 24 h after infection were determined by plaque assay on BHK cells. Data are shown as percentages of control values. (B, D, and E) C3H/He MEFs in 96-well plates were preloaded with Fluo-4NW (Molecular Probes) for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were then either mock infected, infected with WNV Eg101 at an MOI of 5 (B and D) or with Sindbis virus or VSV (MOI of 5) (E), or infected in the presence of 20 μM chloroquine. (D) Cells were incubated with UV-inactivated WNV Eg101 (equivalent to an MOI of 5) in the presence or absence of chloroquine (Chl). Fluorescence was measured at 5-min intervals in a Victor 3 1420 multilabel plate reader (Perkin Elmer). The data points are averages for six measurements.

A calcium fluorescence-based flux assay was used to assess Ca2+ mobilization after WNV infection. C3H/He MEFs were preloaded with Fluo-4NW, which freely diffuses into cells. The binding of free cytosolic Ca2+ to Fluo-4NW inside cells causes it to fluoresce. Preloaded cells were incubated with either culture medium or WNV at an MOI of 5 for 2 h, and fluorescence was measured at 5-min intervals. Intracellular Ca2+ levels were observed to increase progressively, starting with the first time point (10 min) and continuing through 2 h, in cells incubated with WNV compared to mock-infected cells (Fig. 1B). Similar results were obtained for replicate experiments done with BHK cells or C57BL/6 MEFs (data not shown). As an alternative means of assessing the effect of reduction of extracellular Ca2+ on virus production, a WNV Eg101 stock in Ca2+-free medium was used to infect C3H/He MEFs at an MOI of 5. Cells were washed three times prior to infection and then maintained after infection in Ca2+-free MEM. No increase in intracellular Ca2+ was observed when cells were infected with WNV in calcium-free medium (Fig. 1B). The virus yield 24 h after infection was decreased about 10-fold compared to the yield from cells maintained in control medium (Fig. 1C). Cell viability, assessed by an MTT assay, was reduced by about 30% at 24 h compared to that of control-infected cells (Fig. 1C), suggesting that extracellular Ca2+ is important for both viral replication and maintaining the viability of infected cells.

Inhibition of endosome acidification during WNV entry reduces Ca2+ influx.

Flaviviruses enter cells by clathrin-dependent endocytosis and require an acidic vacuolar pH for virion membrane fusion to occur during virion uncoating (12, 24). Previous studies have shown that extracellular Ca2+ can enter cells in endosomes and that endosome acidification allows Ca2+ to be released into the cytoplasm (18, 30). Incubation of cells with 20 μM chloroquine or 1 mM amantadine (lysosomotropic weak bases that prevent vesicle acidification and virus membrane fusion) during virus adsorption/entry was previously reported to cause a marked reduction in the infection of Vero cells, in a dose-dependent manner (as indicated by a reduced number of viral envelope protein-expressing cells 12 h after infection) (12).

C3H/He MEFs were pretreated with 20 μM chloroquine or 1 mM amantadine for 30 min and then infected with WNV Eg101 at an MOI of 5 for 1 h in the presence of the same drug. The monolayers were washed to remove unadsorbed virus, and cells were maintained in the presence of the same drug. Twenty-four hours after infection, the virus yields produced by cells treated with either drug were reduced by almost 100% compared to those from untreated cells (Fig. 1C). Possible cytotoxic effects of these drugs were assessed by a trypan blue exclusion assay as well as by an MTT assay. No cell toxicity was observed in drug-treated cells throughout the experiments (Fig. 1C and data not shown). To test whether endocytosis and subsequent endosome acidification contributed to the observed increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels, the effect of chloroquine on the increase in intracellular Ca2+ after WNV infection was next analyzed. C3H/He MEFs were preloaded with Fluo-4NW in the presence of 20 μM chloroquine and then incubated with WNV Eg101 at an MOI of 5 in the presence of the same concentration of drug for 2 h. Although intracellular Ca2+ levels still increased in infected, chloroquine-treated cells, a significant reduction in Ca2+ influx was observed at all times in cells incubated with chloroquine compared to cells incubated only with virus (Fig. 1D). The results indicate that Ca2+ entry during endocytosis contributes to the observed Ca2+ influx after WNV infection.

Analysis of Ca2+ influx in C3H/He MEFs infected with other types of enveloped single-stranded RNA viruses.

Sindbis virus is an alpha togavirus with a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome, while VSV is a rhabdovirus with a negative-sense, single-stranded RNA genome. Both of these viruses have been reported to enter cells by endocytosis (34). To our knowledge, there are no previous reports on the involvement of Ca2+ in the life cycles of these viruses. To determine whether Sindbis virus or VSV infection triggers Ca2+ influx, Fluo-4NW-preloaded MEFs were incubated with either culture medium, Sindbis virus (MOI of 5), or VSV (MOI of 5) for 2 h, and fluorescence was measured at 5-min intervals. Intracellular Ca2+ levels were observed to increase progressively through 2 h in cells incubated with Sindbis virus compared to mock-infected cells (Fig. 1E), but little, if any, increase was observed in VSV-infected cells. VSV was previously reported to be delivered to early endosomes within 1 to 2 min after addition to cells and can fuse there (34). To determine whether a burst of intracellular Ca2+ occurred prior to 5 min, measurements were repeated at 30-s intervals between 1 and 5 min. About 1 min was required to set up the infection wells and to place them in the plate reader. No increase in Ca2+ levels was detected within the first 5 min of infection with VSV (data not shown), indicating that VSV entry differs from that of both Sindbis virus and WNV in regard to inducing Ca2+ influx.

The effect of chloroquine on the influx of Ca2+ after Sindbis virus and VSV infections was also analyzed. No significant increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels was detected in chloroquine-treated, Sindbis virus- or VSV-infected MEFs compared to mock-infected cells (Fig. 1E), suggesting that the observed increase in Ca2+ levels in Sindbis virus-infected cells was mediated entirely by the endocytotic process.

Analysis of the effects of Ca2+ channel inhibitors on virus yield.

To assess whether some of the Ca2+ influx observed in chloroquine-treated, WNV-infected cells occurred through Ca2+ channels, cells were incubated with a Ca2+ channel inhibitor prior to, during, and after infection. Three different classes of Ca2+ channel blockers, i.e., phenylalkylamines (verapamil), benzothiazepines (diltiazem), and dihydropyridines (nifedipine), were tested. Each of these drugs was previously shown to inhibit voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, ligand-gated Ca2+ channels, and some nonselective cation channels at micromolar concentrations (16, 26, 47). However, nifedipine was reported to have the greatest inhibitory effect as an L-type calcium antagonist (49). MEFs were pretreated with 50 μM verapamil or nifedipine or with 100 μM diltiazem for 2 h. The cells were then either mock infected or infected with WNV Eg101 at an MOI of 5 for 1 h in the presence of the same drug. The monolayers were washed to remove unadsorbed virus and were maintained thereafter in medium containing drug for either 2 or 20 additional hours, followed by replacement with fresh medium. Virus infectivity in samples of culture fluid collected at the indicated times was assessed by plaque assay on BHK cells. Only a slight decrease in the peak virus titer was observed when cells were treated with verapamil or diltiazem for 2 h after infection, but virus titers were reduced ∼5- to 10-fold when these drugs were present in the medium for 20 h after infection (Fig. 1F). In contrast, nifedipine reduced virus yields 50-fold after 2 h of drug treatment and 10,000-fold after 20 h of treatment compared to the yields from vehicle-treated cells. Twenty-eight and 42 h after infection, the levels of virus produced were also reduced 50-fold compared to those for untreated cells (Fig. 1F). Evidence of minimal cytotoxicity was observed in uninfected C3H/He MEFs 24 h after incubation with 50 μM nifedipine for 20 h, as assessed by MTT cell proliferation assay (Fig. 2 C). The reduced virus yields observed from cells treated with either extracellular Ca2+ chelators or Ca2+ channel blockers suggested that the Ca2+ influx triggered by WNV infection enhanced the efficiency of virus production.

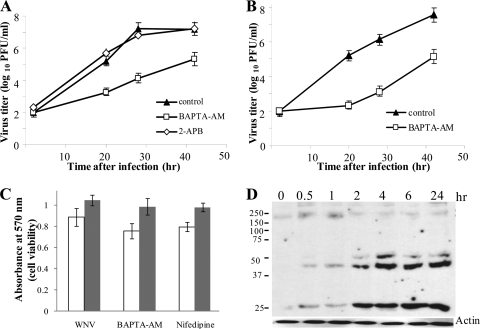

FIG. 2.

Intracellular Ca2+ is important for efficient WNV production. Confluent monolayers of C3H/He (A) or C57BL/6 (B) MEFs were pretreated with 25 μM BAPTA-AM or 100 μM 2-APB (A) for 0.5 h. The cells were then either mock infected or infected with WNV at an MOI of 5 for 1 h in the presence of drug and were maintained thereafter in medium with drug for 2 h after infection, followed by replacement with fresh medium. Samples of culture fluid were harvested at the indicated times, and titers were determined by plaque assay on BHK cells. Error bars indicate ±SD (n = 3). Control, 0.1% DMSO. (C) Cell viability was measured by MTT assay. White bars, C3H/He MEFs; gray bars, BHK cells infected with WNV Eg101 and treated with BAPTA-AM (as described in the legend to Fig. 1) or nifedipine (20 h). (D) C3H/He MEFs were serum starved for 3 h before infection with WNV Eg101 at an MOI of 10. Cell extracts were prepared 30 min and 1, 2, 4, and 6 h after infection and were analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-P-Tyr antibody.

Analysis of the effects of an intracellular Ca2+ chelator on virus yield.

The effect on viral yield of loading cells with the intracellular Ca2+ chelator BAPTA-AM (an acetoxymethyl ester derivative of BAPTA) prior to infection was next analyzed. Previous studies showed that incubation of cells with BAPTA-AM at concentrations ranging from 20 to 50 μM for 2 to 3 h caused no detectable cytopathology. Consistent with these observations, evidence of minimal cytotoxicity was observed in uninfected C3H/He or C57BL/6 MEFs 24 h after incubation with 25 μM BAPTA-AM for 3 h, as assessed by trypan blue exclusion (data not shown) and by MTT assay (Fig. 2C). C3H/He MEFs were infected with WNV at an MOI of 5 for 1 h in the presence of 25 μM BAPTA-AM or 0.1% DMSO (vehicle). The cell monolayers were washed to remove unadsorbed virus and were incubated with medium containing 25 μM BAPTA-AM for 2 h and then with medium without drug. Twenty, 28, and 48 h after infection, an ∼100-fold decrease in virus yield was observed compared to that from infected cells not treated with drug (Fig. 2A). When the same experiment was repeated using C57BL/6 MEFs, an ∼1,000-fold decrease in virus yield was observed at each of the times tested (Fig. 2B). The results also support the hypothesis that an increase in intracellular Ca2+ ions during the first 2 h of infection is important for efficient WNV production.

It was previously reported that BAPTA-AM interferes with endoplasmic reticulum (ER) functions, most probably by disturbing ER calcium homeostasis (38). The ER is the main storage site for intracellular Ca2+, and mobilization of Ca2+ from this store is an essential triggering signal for downstream events, including activation of phosphorylation pathways. The observed effect of BAPTA-AM on the efficiency of WNV production could be due to its effect on cytoplasmic Ca2+ homeostasis and/or to its effect on ER Ca2+ homeostasis. To determine whether release of ER Ca2+ stores occurred in WNV-infected cells, the effects of 2-APB on WNV yields were analyzed. 2-APB is an inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) receptor antagonist that prevents IP3-mediated release of ER Ca2+. In a preliminary experiment with uninfected cells, no cytotoxicity was observed in C3H/He MEF cultures incubated with 100 μM 2-APB for 48 h, as assessed by trypan blue exclusion (data not shown). C3H/He MEFs were next incubated for 2 h with 100 μM 2-APB or 0.1% DMSO (vehicle) and then mock infected or infected with WNV Eg101 at an MOI of 5 for 1 h in the presence of the same drug concentration. The monolayers were washed to remove unadsorbed virus and then incubated with medium containing 100 μM 2-APB for 2 h or 20 h, followed by replacement with medium without drug. No effect on virus yields was observed with a 2-h 2-APB treatment (Fig. 2A), indicating that the initial stages of WNV infection are not enhanced by ER Ca2+ release. Even though no effect on viability was observed for uninfected cells incubated with 100 μM 2-APB for 48 h, ∼50% of WNV-infected cells treated with 2-APB for 20 h showed a cytopathic effect (CPE) (rounded and detached), suggesting that blocking ER calcium release for longer than 2 h in WNV-infected cells triggered rapid cell death (data not shown).

WNV infection of MEFs triggers phosphorylation signaling cascades.

Ca2+ has previously been reported to trigger several phosphorylation-mediated cell signaling pathways (5). The global signaling status of cells during the initial stages of infection with WNV was first assessed using a Kinex antibody microarray (Kinexus, Vancouver, Canada). Second-passage primary C3H/He MEFs were used for this assay to avoid detection of signaling variations that might be caused by cell transformation. MEFs that were either mock infected or infected with WNV Eg101 at an MOI of 10 for 1 h were harvested and lysed, and the lysates were sent to Kinexus for analysis. Significant changes in phosphorylation status were observed for particular kinases, including FAK, at S843 and Y576/577; ERK1/2 and p44/p42 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases, at T202 and Y204; Akt1, at Ser473; PKC, at T638 and T641; signal transducer and activator of transcription protein (STAT) 5A, at Y694; ribosomal S6 protein-serine kinase 1 (RSK), at T573/T577; and p70 ribosomal protein-serine S6 kinase alpha (S6Ka), at T389, T421+S424, and T229 (data not shown). To determine whether changes in protein expression levels could account for the observed increases in phosphorylation, Kinexus performed a protein quantity analysis. The amounts of the kinases that showed increased phosphorylation remained similar to those in control samples.

Phosphorylation of tyrosines in various cellular proteins was previously observed in conjunction with Ca2+-mediated signaling (40, 50). To determine whether Tyr phosphorylation occurred in WNV-infected cells, MEFs were serum starved for 3 h prior to infection with WNV Eg101 (MOI of 5), and cell lysates harvested at early times after infection were analyzed by immunoblotting, using a phospho-Tyr-specific antibody. Several Tyr-phosphorylated proteins were detected by 30 min after WNV infection (Fig. 2D). Phosphorylation of tyrosines in some of these proteins decreased after 1 h of infection, while phosphorylation of others increased with the time after infection (Fig. 2D).

WNV infection activates FAK and ERK.

FAK is a nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinase that was initially reported to be a component of integrin-stimulated signaling pathways (8). However, FAK activation can also be mediated by stimulation of G-protein-coupled receptors and by various cytokines or by increases in cytosolic Ca2+ levels (44). Following activation (indicated by autophosphorylation at Tyr397), FAK recruits and activates members of the Src kinase family. The phosphorylation of FAK by Src (or other Src family kinases) at tyrosines 576 and 577 results in full activation of FAK and ultimately leads to activation of downstream targets, such as ERKs and c-Jun N-terminal kinases (44). Ca2+-dependent classical PKC isoforms (alpha, beta I, beta II, and gamma) represent a family of second messenger-dependent protein kinases that are stimulated by Ca2+ and play a role in mediating cellular responses to extracellular stimuli in a number of systems (33). Control of PKC activity is regulated through three distinct phosphorylation events: phosphorylation of Thr500, located in the PKC activation loop, as well as autophosphorylation of Thr641 and the carboxy-terminal hydrophobic site Ser660 (22). To confirm the results obtained in the Kinexus analysis, the phosphorylation status of the FAK, ERK, and PKC kinases was assessed by Western blotting, using lysates from WNV-infected C3H/He MEFs and BHK cells.

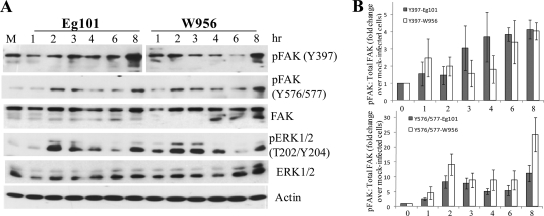

To test whether different WNV strains might differentially induce cell kinase activation, cells were infected with either WNV Eg101 (lineage 1) or WNV W956 (lineage 2). The majority of WNV isolates are classified into one of these two lineages. Most lineage 1 strains are neuroinvasive, while most lineage 2 strains are not (4). Phosphorylation at FAK Tyr397, FAK Tyr576/577, and ERK Thr202/Tyr204 was detected by immunoblotting, using phospho-protein-specific antibodies (Fig. 3). Increased phosphorylation of FAK and ERK at the sites assayed was detected as early as 1 h after infection. Phosphorylation at each of these sites was sustained through later times of infection in both BHK cells (Fig. 3A) and C3H/He cells (data not shown) infected with either strain of WNV, indicating that the activation of these kinases is a general characteristic of infections with different strains of WNV.

FIG. 3.

WNV infection induces phosphorylation of FAK and ERK1/2. (A) BHK cells were infected with WNV Eg101 or W956 at an MOI of 5. At the indicated times after infection, cell lysates were prepared and proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to membranes, and analyzed by Western blotting, using antibodies specific for the indicated protein phosphorylation sites, as described in Materials and Methods. Actin was used as a loading control. (B) Results obtained from three independent experiments are summarized graphically as fold changes in the ratio of optical density units (ODU) of phosphorylated FAK to ODU of total FAK divided by the ratio for mock-infected cells. Error bars indicate ±SD.

Activation of FAK in WNV-infected cells is not dependent on αvβ3 integrin.

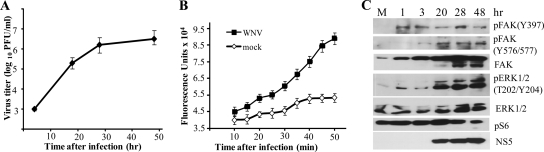

The activation of FAK in WNV-infected cells was previously suggested by Chu and Ng (13) to be the result of attachment of WNV to the cell surface integrin αvβ3. However, a subsequent study found that WNV was capable of efficiently infecting CS-1 cells (32), a hamster melanoma cell line grown in suspension that does not express β3 integrin (17, 48). Analysis of the growth kinetics of WNV Eg101 (MOI of 1) in CS-1 cells confirmed that these cells can be infected productively by WNV (Fig. 4 A). Intracellular Ca2+ levels detected by a Fluo-4NW calcium fluorescence assay increased with time after infection in CS-1 cells (Fig. 4B). The kinetics of this increase were similar to those detected in WNV-infected MEFs and BHK cells (Fig. 1). The activation of FAK and ERK in WNV-infected CS-1 cells was analyzed by immunoblotting, using phospho-specific antibodies for FAK Tyr397, FAK Tyr576/577, and ERK Thr202/Tyr204. Increased phosphorylation of FAK and ERK at each of these sites was observed in infected CS-1 cells by 1 h after infection (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that neither the increase in intracellular Ca2+ nor the FAK and ERK activation that occurs after WNV infection depends on the expression of β3 integrin. These data do not rule out the possibility that other integrins may be involved.

FIG. 4.

WNV infection induces FAK and ERK1/2 phosphorylation and increases intracellular Ca2+ levels in CS-1 hamster melanoma cells. (A) CS-1 cells infected with WNV Eg101 at an MOI of 5. Samples of culture fluid were harvested at the indicated times, and titers were determined by plaque assay on BHK cells. Error bars indicate ±SD (n = 3). (B) CS-1 cells seeded in 96-well plates were loaded with Fluo-4NW for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were then incubated with WNV Eg101 at an MOI of 5 or mock infected for 1 h. Fluorescence was measured at 5-min intervals in a Victor 3 1420 multilabel plate reader (Perkin Elmer). The averages of three measurements were plotted. (C) CS-1 cells infected with WNV Eg101 at an MOI of 5. Cell lysates were harvested at the indicated times after infection. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting, using antibodies specific for the indicated protein sites, as described in Materials and Methods. The total ERK proteins were used as the loading control.

UV-inactivated WNV induces early activation of FAK and ERK1/2.

To determine whether nonreplicating viral particles could also induce FAK and ERK1/2 activation, the kinetics of phosphorylation of these kinases were analyzed in C3H/He MEFs incubated with UV-inactivated WNV at a concentration equivalent to an MOI of 5 PFU/cell. Cell lysates collected 1, 2, 3, and 20 h after addition of UV-inactivated virus were analyzed by Western blotting, using phospho-specific FAK and ERK1/2 antibodies. Increases in the phosphorylation of both kinases, to levels similar to those observed in cells infected with nonirradiated virus, were observed 1 h after addition of UV-inactivated virus (Fig. 5 A). However, activation was not sustained beyond 1 h, suggesting that subsequent steps of the virus life cycle are required to maintain FAK and ERK1/2 activation. To test whether UV-inactivated virus can trigger an increase in Ca2+ levels inside cells, C3H/He cells were preloaded with Fluo-4NW and incubated either with WNV Eg101 at an MOI of 5 or with UV-inactivated virus at an equivalent MOI, and fluorescence was measured at 5-min intervals. Decreased intracellular Ca2+ levels similar to those detected after chloroquine treatment of WNV Eg101-infected cells were observed (Fig. 1D). The effect of chloroquine on the Ca2+ influx mediated by UV-inactivated virus was next tested under the same conditions as those described for WNV Eg101. The kinetics and levels of cytosolic Ca2+ observed in cells incubated with UV-inactivated virus and treated with chloroquine were similar to those in cells incubated with only UV-inactivated virus (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that UV-inactivated virus cannot induce endocytosis-mediated Ca2+ entry but does induce Ca2+ entry through opening of Ca2+ channels.

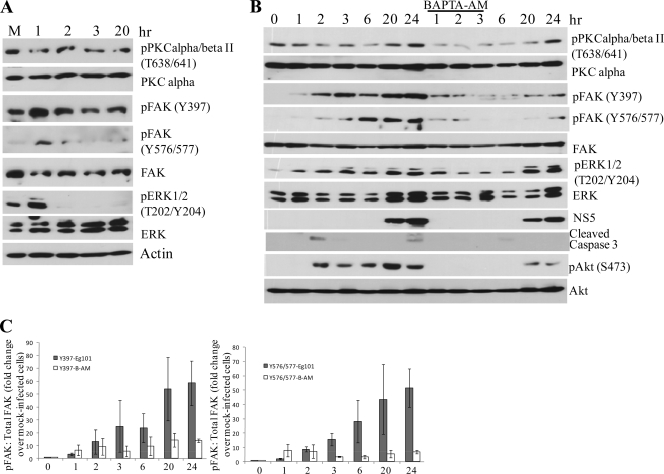

FIG. 5.

Sustained WNV-mediated activation of FAK requires replicating virus and is Ca2+ dependent. C3H/He MEFs were incubated with UV-inactivated WNV Eg101 (equivalent to an MOI of 5) (A) or were mock infected, infected with WNV at an MOI of 5 for the indicated periods, or infected in the presence of 25 μM BAPTA-AM and maintained thereafter in medium with drug for 2 h after infection, followed by replacement with fresh medium (B and C). Cell lysates were prepared at the indicated times after infection. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting, using antibodies specific for the indicated protein sites. Actin was used as a loading control. (C) Results obtained from three independent experiments are summarized graphically as fold changes in the ratio of ODU of phosphorylated FAK to ODU of total FAK divided by the ratio for mock-infected cells. Error bars indicate ±SD.

Early FAK and ERK activation in WNV-infected cells is Ca2+ dependent.

The intracellular Ca2+ chelator BAPTA-AM was next used to determine whether Ca2+ influx was required for activation of ERK and FAK during the initial stages of a WNV infection. Because data from several previous studies indicated that PKC plays an important role in regulating receptor-mediated endocytosis of virus-receptor complexes, through promotion of endosome-endosome fusion followed by trafficking of internalized virus along the endosomal-lysosomal pathway, the activation of PKC was also analyzed (31, 45). C3H/He MEFs were infected with WNV at an MOI of 5 for 1 h in the presence of 25 μM BAPTA-AM or 0.1% DMSO (vehicle). The cell monolayers were washed to remove unadsorbed virus and were incubated with medium containing 25 μM BAPTA-AM for 2 h and then with medium without drug. Cell lysates were collected 1, 2, 3, 6, 20, and 24 h after infection and were analyzed by Western blotting, using phospho-specific antibody. In BAPTA-AM-treated, WNV-infected cell extracts, PKC alpha/beta II phosphorylation at Thr638/641 was reduced at every time point tested prior to 24 h compared to the levels observed in untreated WNV-infected cells (Fig. 5B, top panels). Since phosphorylation of the PKC alpha/beta isoforms is known to be Ca2+ dependent, the observed reduction in their activation in drug-treated cells confirmed that BAPTA-AM had efficiently chelated intracellular Ca2+.

Several previous studies reported that FAK autophosphorylation at Tyr397 increased as intracellular Ca2+ levels increased (1, 2, 19, 51). To test whether the increased autophosphorylation at FAK Tyr397 in WNV-infected cells was Ca2+ dependent, lysates from WNV-infected cells as well as those from BAPTA-AM-treated, WNV-infected C3H/He MEFs were analyzed by Western blotting, using phospho-specific antibody to FAK Tyr397 or FAK Tyr576/577. Increased FAK autophosphorylation at Tyr397 as well as at Tyr576/577 was observed at all times tested after WNV infection (Fig. 5B, middle panels). The lower level of phosphorylation at Tyr397 6 h after infection (on the blot shown) was not seen with replicate samples (Fig. 5C). Reduced phosphorylation of FAK was observed in BAPTA-AM-treated, WNV-infected MEFs at all times after infection compared to WNV-infected MEFs, suggesting that virus-induced FAK activation is Ca2+ dependent (Fig. 5B and C). Reduced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was also observed through 6 h after infection in the BAPTA-AM-treated samples, indicating that ERK activation was also Ca2+ dependent. Phosphorylated FAK recruits Src family kinases, such as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K). PI3K is a known activator of Akt. Akt phosphorylation was previously observed to occur at early times after Japanese encephalitis virus and dengue virus 2 infections of N18 cells (a mouse neuroblastoma cell line) and to be both PI3K and lipid raft dependent (25). Activation of Akt signaling was shown to be essential for blockade of caspase-dependent apoptotic cell death at the early stages of infection with these two viruses (24). Caspase 3 cleavage was analyzed by Western blotting as a marker of activation of apoptosis pathways, using a caspase 3 cleavage-specific antibody. A cleaved caspase 3 band was clearly detected at 2 h, and a weaker band was visible on the film 3 h after infection with WNV (Fig. 5B, left side). Akt activation, as indicated by phosphorylation at Ser473, was detected in both C3H/He (Fig. 5B, left side) and BHK (data not shown) cells by 2 h after infection with WNV Eg101 and was sustained during infection. The time course of FAK activation was similar to that of Akt activation (Fig. 5B, left side).

To test whether the observed early caspase 3 cleavage and Akt activation in WNV-infected cells were Ca2+ dependent, lysates from WNV-infected cells and BAPTA-AM-treated, WNV-infected C3H/He MEFs were compared by Western blot analysis. BAPTA-AM treatment during virus adsorption and for 2 h after infection prevented detectable cleavage of caspase 3 and Akt phosphorylation in MEFs at early times after infection (Fig. 5B, right side). A weak band of cleaved caspase 3 was detected 6 h after infection in BAPTA-AM-treated cells. Akt activation was also delayed and occurred to a lesser extent in BAPTA-AM-treated cells, suggesting that early caspase 3 cleavage and Akt activation are Ca2+ dependent. The results suggest that virus-induced early Ca2+ influx results in transient activation of apoptosis pathways, which in turn induces activation of the Akt-mediated survival pathway. The lower levels of viral NS5 protein detected confirmed the observed lower virus yields from BAPTA-AM-treated cells (Fig. 2A) and indicated that Ca2+ signaling is also important for early replication events needed for efficient virus production.

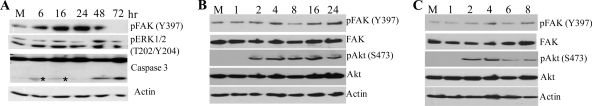

To test whether FAK and ERK1/2 activation in WNV-infected cells correlates with cell survival at later time points, the cleavage of caspase 3 was analyzed by Western blotting using WNV-infected C3H/He and BHK cell lysates made at later times after infection. Increased levels of caspase 3 cleavage were observed 48 and 72 h after infection for C3H/He MEFs (Fig. 6 A) and 28 and 42 h after infection for BHK cells (Fig. 7 A). Increased caspase 3 cleavage correlated with decreased FAK and ERK1/2 phosphorylation at later times after infection. The detection of caspase 3 cleavage in infected BHK cells by 28 h, compared to 48 h for MEFs, was consistent with the earlier appearance of virus-induced CPE in BHK cells. The activation of FAK and Akt kinases was also analyzed in C3H/He cells infected with Sindbis virus and VSV. No significant increase in FAK phosphorylation over that in mock-infected cells was detected in cells infected with either virus (Fig. 6B and C). However, phosphorylation of Akt was detected in cells infected with either Sindbis virus or VSV by 2 h after infection, which was similar to the activation kinetics observed in WNV-infected cells. In both Sindbis virus- and VSV-infected cells, the levels of pAkt decreased at the times when virus-induced CPE began to be observed (6 to 8 h for VSV and 20 to 24 h for Sindbis virus). These results indicated that neither Sindbis virus nor VSV infections trigger the activation of FAK in MEFs, indicating that the Akt activation observed after infections with these viruses is FAK independent.

FIG. 6.

WNV infections, but not VSV or Sindbis virus infections, induce phosphorylation of FAK. C3H/He MEFs were mock infected or infected with WNV at an MOI of 5 for the indicated periods (A) or were infected with Sindbis virus (B) or VSV (C) at an MOI of 10. Cell lysates were prepared at the indicated times after infection. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting, using antibodies specific for the indicated protein sites. Asterisks indicate nonspecific bands. Actin was used as a loading control.

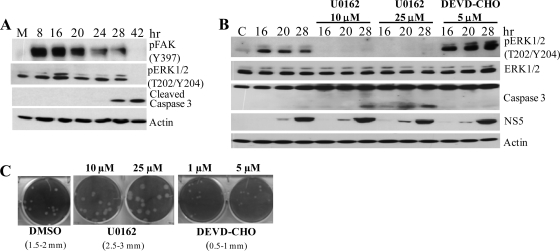

FIG. 7.

Detection of ERK1/2 activation and caspase 3 cleavage. (A) BHK cells were infected with WNV Eg101 at an MOI of 5 and then incubated with medium containing either 0.1% DMSO (solvent), 10 or 25 μM U0126, or 5 μM DEVD-CHO. At the indicated times after infection, cell lysates were prepared. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting, using antibodies specific for the indicated protein phosphorylation sites. Actin was used as a loading control. The blots shown are representative of the results obtained from three independent experiments. (B) BHK cells were infected with WNV Eg101 at an MOI of 5. Cell lysates were harvested at the indicated times after infection. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting, using antibodies specific for the indicated protein sites, as described in Materials and Methods. Actin was used as a loading control. (C) Effects of incubation of infected cells with MEK and caspase 3 inhibitors on plaque size. Confluent monolayers of BHK cells were infected with serial 10-fold dilutions of WNV and incubated under 1% agarose for 72 h in the presence of DMSO or one of the indicated inhibitors. The plaque size is shown for each condition.

Activation of the ERK1/2 pathway contributes to cell survival after virus infection.

U0126, an inhibitor of MEK, the kinase that phosphorylates ERK1/2, was used as an additional means of analyzing the importance of ERK pathway activation for the survival of WNV-infected cells. BHK cells were infected with WNV Eg101 at an MOI of 5 for 1 h and then washed to remove unadsorbed virus. The cells were then incubated with medium containing 10 or 25 μM U0126. Western blot analysis of cell lysates, using anti-phospho-ERK1/2 antibody, confirmed that ERK activation was inhibited by incubation of cells with either 10 or 25 μM U0126 (Fig. 7B). Caspase 3 cleavage occurred earlier and to a greater extent in U0126-treated cells than in untreated cells. The effect of the caspase 3 inhibitor DEVD-CHO was also assessed. Treatment of cells with 5 μM DEVD-CHO decreased caspase 3 cleavage and markedly increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation 16, 20, and 28 h after infection, suggesting the existence of a feedback loop. Extracellular virus growth curves generated from cells treated with either of the two concentrations of U0126 or with DEVD-CHO were identical to that generated from control cells (data not shown). The amounts of NS5 protein produced, detected by Western blot analysis, were also similar (Fig. 7B). To assess the efficiency of virus-induced cell death, the diameters of viral plaques produced by 10−5 dilution of media harvested 28 h after infection from drug-treated and control cells were compared (Fig. 7C). In the presence of DMSO (vehicle), the viral plaque diameters ranged from 1.5 to 2 mm (Fig. 7C); they increased to 2.5 to 3 mm when the cell monolayers were overlaid with medium containing the MEK1/2 inhibitor U0162, and they decreased to 0.5 to 1 mm when the cell monolayers were incubated with medium containing DEVD-CHO. The observed correlation between the level of caspase 3 cleavage and plaque size as an indicator of cell death supports the hypothesis that WNV-induced activation of the ERK pathway results in prolonged survival of WNV-infected cells.

DISCUSSION

The cellular pathways activated and/or used to remodel cells during a WNV infection have not been delineated fully. It has been reported for other types of viruses that virus-induced increases in cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels due to either virus-induced influx of extracellular Ca2+ or release of Ca2+ from internal stores, such as the ER and mitochondria, can enhance virus replication by activating or accelerating a number of Ca2+-dependent enzymatic processes in the cytosol and/or by upregulating Ca2+-sensitive transcriptional factors (55). In the present study, a fluorescence-based calcium assay showed that intracellular Ca2+ levels continued to increase during a 2-h incubation period with WNV at an MOI of 5 in several types of cell lines. Activation of some G-coupled receptors produces a rapid spike of Ca2+ within seconds, followed by a gradual rise in intracellular Ca2+. Whether a transient Ca2+ spike occurred immediately after WNV addition could not be determined, because the infected tissue culture wells had to be sealed inside a biosafety level 3 (BSL3) lab and then transported to the plate reader, which was located in the core facility.

The intracellular Ca2+ concentration (∼100 nM) is much lower than the extracellular Ca2+ concentration (1 to 2 mM). Extracellular fluid containing Ca2+ is taken up by endocytotic vesicles, and this Ca2+ is subsequently extruded into the cytoplasm from endosomes as endosomal acidification occurs (18). Chloroquine, a weak base, diffuses across vesicle membranes, becomes protonated, and thereby neutralizes the acidic environment of endocytic vesicles. Chloroquine was previously shown to negatively affect the entry of flaviviruses as well as that of a number of other enveloped viruses that undergo low-pH-dependent fusion following endocytosis (23). The observation in the present study that incubation of WNV-infected cells with chloroquine reduced the increase in intracellular Ca2+ by only about half compared to that in untreated infected cells suggested that although Ca2+ was released from acidified endocytic vesicles during the initial stages of infection, Ca2+ also entered by an additional mode. Incubation of cells with Ca2+ channel blockers for only 2 h immediately after virus adsorption had a negative effect on viral yields that continued through 48 h, suggesting that the influx of Ca2+ through channels has the greatest effect during the early phases of the infection. Which cell surface Ca2+ channel(s) is activated by WNV infection is not currently known. It was recently reported that WNV utilizes lipid rafts during the initial stages of virion internalization (32) and that virion membrane fusion during entry is strongly promoted by the presence of cholesterol in the target cell membrane (35). Cholesterol domains in lipid rafts have been shown to contain multiple signaling complexes, including regulators and ion channels involved in Ca2+ signaling (37). The data obtained suggest that WNV attachment and/or entry triggers the opening of one or more of the Ca2+ channels on the cell surface. This was not found to be the case for infections with either VSV or Sindbis virus.

None of the Ca2+ inhibitors used in the current study had any effect on virus yield when they were present during the virus adsorption period, indicating that they did not affect WNV entry. However, their presence during the first 2 h after infection resulted in decreased virus yields. These results indicate that Ca2+ signaling is important for early replication events, possibly ER membrane rearrangements and other cell modifications required for efficient flavivirus replication.

The observations that the kinetics and levels of Ca2+ influx for cells incubated with UV-inactivated virus were about half those for cells incubated with nonirradiated virus and did not change when the cells were incubated with UV-inactivated virus and treated with chloroquine indicated that UV-irradiated virus could induce Ca2+ influx through channels but not through endosome acidification. Consistent with what has previously been reported for UV-inactivated enveloped virions (9, 27, 36, 39, 52), the data obtained in this study indicate that UV-inactivated WNV attaches to unknown receptors and activates early signaling events, but only transiently.

FAK autophosphorylation can be activated by integrin clustering (20). Although a previous study suggested that αvβ3 integrin is a cell receptor for WNV (13), other studies (15, 32) and the present study showed that cells that do not express β3 integrin can be infected efficiently with WNV. In the present study, the increases in cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels and FAK autophosphorylation levels were shown to be similar in infected cells that efficiently express β3 integrin and those that do not. FAK autophosphorylation has also been shown to increase with increasing intracellular Ca2+ levels (19, 44). The observation in this study that chelation of intracellular Ca2+ by BAPTA-AM attenuated virus-induced phosphorylation of FAK suggested that FAK activation was the result of Ca2+-mediated signaling.

Autophosphorylation at Tyr397 is a key event in the activation of FAK because it creates a binding site for the recruitment of a number of SH2- and SH3-domain-containing proteins, including c-Src, Fyn, Grb7, and others (41). FAK recruits and activates Src, which in turn phosphorylates FAK, further enhancing FAK activity. This creates a positive feedback loop that leads to the activation of downstream signaling molecules, such as ERK and PI3K/Akt. WNV infection resulted in an early and sustained activation of FAK, ERK1/2, and PI3K/Akt in mammalian cells, while UV-inactivated virus failed to maintain phosphorylation of these kinases beyond 1 h after infection, indicating that sustained activation requires virus replication. A previous study reported that infections with two other flaviviruses, Japanese encephalitis virus and dengue virus, activated the PI3K/Akt pathway at early times after infection (25). It was suggested that activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway might play an antiapoptotic role in infected cells. It has also been demonstrated that FAK can inhibit cell apoptosis via activation of PI3K/Akt (46, 53). In coxsackievirus B3-infected cells, activation of the PI3K/Akt survival pathway by gamma interferon-inducible GTPase was shown to be FAK dependent (29). Akt kinase activation was not observed in BAPTA-AM-treated, WNV-infected cells at early times after infection, suggesting that Akt activation in WNV-infected cells is mediated by Ca2+ signaling. Support for the hypothesis that activation of the PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 pathways by FAK contributes to the survival of flavivirus-infected cells was provided by the observation that the levels of FAK and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in WNV-infected cells inversely correlated with the level of caspase 3 cleavage, a marker of apoptosis. Also, treatment of WNV-infected cells with a MEK inhibitor, which prevents phosphorylation of the ERK1/2 kinase, increased both the efficiency of cell death, as indicated by an increase in the diameter of viral plaques, and the level of caspase 3 cleavage. The ERK1/2 pathway is one of the antiapoptotic signaling pathways in WNV-infected cells, and the balance between all of the survival mechanisms (Akt, ERK, and others) and the apoptotic signaling triggered at later stages of infection defines the outcome of infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service research grant AI045135 to M.A.B. from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

We thank David Cheresh, University of California, San Diego, CA, for providing CS-1 cells with permission of Caroline Damsky, Pei-Yong Shi for providing NS5 antibody, and B. Stockman for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 June 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achison, M., C. M. Elton, P. G. Hargreaves, C. G. Knight, M. J. Barnes, and R. W. Farndale. 2001. Integrin-independent tyrosine phosphorylation of p125(fak) in human platelets stimulated by collagen. J. Biol. Chem. 276:3167-3174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alessandro, R., L. Masiero, K. Lapidos, J. Spoonster, and E. C. Kohn. 1998. Endothelial cell spreading on type IV collagen and spreading-induced FAK phosphorylation is regulated by Ca2+ influx. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 248:635-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alfano, M., H. Schmidtmayerova, C. A. Amella, T. Pushkarsky, and M. Bukrinsky. 1999. The B-oligomer of pertussis toxin deactivates CC chemokine receptor 5 and blocks entry of M-tropic HIV-1 strains. J. Exp. Med. 190:597-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beasley, D. W., L. Li, M. T. Suderman, and A. D. Barrett. 2002. Mouse neuroinvasive phenotype of West Nile virus strains varies depending upon virus genotype. Virology 296:17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berridge, M. J., M. D. Bootman, and H. L. Roderick. 2003. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4:517-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouchard, M. J., L. H. Wang, and R. J. Schneider. 2001. Calcium signaling by HBx protein in hepatitis B virus DNA replication. Science 294:2376-2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carafoli, E. 2002. Calcium signaling: a tale for all seasons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:1115-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cary, L. A., D. C. Han, and J. L. Guan. 1999. Integrin-mediated signal transduction pathways. Histol. Histopathol. 14:1001-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ceballos-Olvera, I., S. Chavez-Salinas, F. Medina, J. E. Ludert, and R. M. del Angel. 2010. JNK phosphorylation, induced during dengue virus infection, is important for viral infection and requires the presence of cholesterol. Virology 396:30-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chami, M., B. Oules, and P. Paterlini-Brechot. 2006. Cytobiological consequences of calcium-signaling alterations induced by human viral proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763:1344-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheshenko, N., B. Del Rosario, C. Woda, D. Marcellino, L. M. Satlin, and B. C. Herold. 2003. Herpes simplex virus triggers activation of calcium-signaling pathways. J. Cell Biol. 163:283-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu, J. J., and M. L. Ng. 2004. Infectious entry of West Nile virus occurs through a clathrin-mediated endocytic pathway. J. Virol. 78:10543-10555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu, J. J., and M. L. Ng. 2004. Interaction of West Nile virus with alpha v beta 3 integrin mediates virus entry into cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279:54533-54541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis, C. B., I. Dikic, D. Unutmaz, C. M. Hill, J. Arthos, M. A. Siani, D. A. Thompson, J. Schlessinger, and D. R. Littman. 1997. Signal transduction due to HIV-1 envelope interactions with chemokine receptors CXCR4 or CCR5. J. Exp. Med. 186:1793-1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis, C. W., H. Y. Nguyen, S. L. Hanna, M. D. Sanchez, R. W. Doms, and T. C. Pierson. 2006. West Nile virus discriminates between DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR for cellular attachment and infection. J. Virol. 80:1290-1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diochot, S., S. Richard, M. Baldy-Moulinier, J. Nargeot, and J. Valmier. 1995. Dihydropyridines, phenylalkylamines and benzothiazepines block N-, P/Q- and R-type calcium currents. Pflugers Arch. 431:10-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filardo, E. J., S. L. Deming, and D. A. Cheresh. 1996. Regulation of cell migration by the integrin beta subunit ectodomain. J. Cell Sci. 109:1615-1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerasimenko, J. V., A. V. Tepikin, O. H. Petersen, and O. V. Gerasimenko. 1998. Calcium uptake via endocytosis with rapid release from acidifying endosomes. Curr. Biol. 8:1335-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giannone, G., P. Ronde, M. Gaire, J. Beaudouin, J. Haiech, J. Ellenberg, and K. Takeda. 2004. Calcium rises locally trigger focal adhesion disassembly and enhance residency of focal adhesion kinase at focal adhesions. J. Biol. Chem. 279:28715-28723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guan, J. L. 1997. Focal adhesion kinase in integrin signaling. Matrix Biol. 16:195-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keay, S., B. R. Baldwin, M. W. Smith, S. S. Wasserman, and W. F. Goldman. 1995. Increases in [Ca2+]i mediated by the 92.5-kDa putative cell membrane receptor for HCMV gp86. Am. J. Physiol. 269:C11-C21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keranen, L. M., E. M. Dutil, and A. C. Newton. 1995. Protein kinase C is regulated in vivo by three functionally distinct phosphorylations. Curr. Biol. 5:1394-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kielian, M., and S. Jungerwirth. 1990. Mechanisms of enveloped virus entry into cells. Mol. Biol. Med. 7:17-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krishnan, M. N., B. Sukumaran, U. Pal, H. Agaisse, J. L. Murray, T. W. Hodge, and E. Fikrig. 2007. Rab 5 is required for the cellular entry of dengue and West Nile viruses. J. Virol. 81:4881-4885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, C. J., C. L. Liao, and Y. L. Lin. 2005. Flavivirus activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling to block caspase-dependent apoptotic cell death at the early stage of virus infection. J. Virol. 79:8388-8399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lenz, T., and J. W. Kleineke. 1997. Hormone-induced rise in cytosolic Ca2+ in axolotl hepatocytes: properties of the Ca2+ influx channel. Am. J. Physiol. 273:C1526-C1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin, R. J., C. L. Liao, and Y. L. Lin. 2004. Replication-incompetent virions of Japanese encephalitis virus trigger neuronal cell death by oxidative stress in a culture system. J. Gen. Virol. 85:521-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, Q. H., D. A. Williams, C. McManus, F. Baribaud, R. W. Doms, D. Schols, E. De Clercq, M. I. Kotlikoff, R. G. Collman, and B. D. Freedman. 2000. HIV-1 gp120 and chemokines activate ion channels in primary macrophages through CCR5 and CXCR4 stimulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:4832-4837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu, Z., H. M. Zhang, J. Yuan, T. Lim, A. Sall, G. A. Taylor, and D. Yang. 2008. Focal adhesion kinase mediates the interferon-gamma-inducible GTPase-induced phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt survival pathway and further initiates a positive feedback loop of NF-kappaB activation. Cell. Microbiol. 10:1787-1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luzio, J. P., N. A. Bright, and P. R. Pryor. 2007. The role of calcium and other ions in sorting and delivery in the late endocytic pathway. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35:1088-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McClure, S. J., and P. J. Robinson. 1996. Dynamin, endocytosis and intracellular signalling. Mol. Membr. Biol. 13:189-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medigeshi, G. R., A. J. Hirsch, D. N. Streblow, J. Nikolich-Zugich, and J. A. Nelson. 2008. West Nile virus entry requires cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains and is independent of alphavbeta3 integrin. J. Virol. 82:5212-5219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mellor, H., and P. J. Parker. 1998. The extended protein kinase C superfamily. Biochem. J. 332:281-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mercer, J., M. Schelhaas, and A. Helenius. 2010. Virus entry by endocytosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79:803-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moesker, B., I. A. Rodenhuis-Zybert, T. Meijerhof, J. Wilschut, and J. M. Smit. 2010. Characterization of the functional requirements of West Nile virus membrane fusion. J. Gen. Virol. 91:389-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noyce, R. S., S. E. Collins, and K. L. Mossman. 2006. Identification of a novel pathway essential for the immediate-early, interferon-independent antiviral response to enveloped virions. J. Virol. 80:226-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pani, B., and B. B. Singh. 2009. Lipid rafts/caveolae as microdomains of calcium signaling. Cell Calcium 45:625-633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paschen, W., S. Hotop, and C. Aufenberg. 2003. Loading neurons with BAPTA-AM activates xbp1 processing indicative of induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Calcium 33:83-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prescott, J., C. Ye, G. Sen, and B. Hjelle. 2005. Induction of innate immune response genes by Sin Nombre hantavirus does not require viral replication. J. Virol. 79:15007-15015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sayeski, P. P., M. S. Ali, and K. E. Bernstein. 2000. The role of Ca2+ mobilization and heterotrimeric G protein activation in mediating tyrosine phosphorylation signaling patterns in vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 212:91-98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaller, M. D., J. D. Hildebrand, J. D. Shannon, J. W. Fox, R. R. Vines, and J. T. Parsons. 1994. Autophosphorylation of the focal adhesion kinase, pp125FAK, directs SH2-dependent binding of pp60src. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:1680-1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scherbik, S. V., J. M. Paranjape, B. M. Stockman, R. H. Silverman, and M. A. Brinton. 2006. RNase L plays a role in the antiviral response to West Nile virus. J. Virol. 80:2987-2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scherbik, S. V., B. M. Stockman, and M. A. Brinton. 2007. Differential expression of interferon (IFN) regulatory factors and IFN-stimulated genes at early times after West Nile virus infection of mouse embryo fibroblasts. J. Virol. 81:12005-12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schlaepfer, D. D., C. R. Hauck, and D. J. Sieg. 1999. Signaling through focal adhesion kinase. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 71:435-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sieczkarski, S. B., H. A. Brown, and G. R. Whittaker. 2003. Role of protein kinase C betaII in influenza virus entry via late endosomes. J. Virol. 77:460-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sonoda, Y., S. Watanabe, Y. Matsumoto, E. Aizu-Yokota, and T. Kasahara. 1999. FAK is the upstream signal protein of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt survival pathway in hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis of a human glioblastoma cell line. J. Biol. Chem. 274:10566-10570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor, C. W., and L. M. Broad. 1998. Pharmacological analysis of intracellular Ca2+ signalling: problems and pitfalls. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 19:370-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas, L., P. W. Chan, S. Chang, and C. Damsky. 1993. 5-Bromo-2-deoxyuridine regulates invasiveness and expression of integrins and matrix-degrading proteinases in a differentiated hamster melanoma cell. J. Cell Sci. 105:191-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Triggle, D. J. 2006. L-type calcium channels. Curr. Pharm. Des. 12:443-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trinkaus-Randall, V., R. Kewalramani, J. Payne, and A. Cornell-Bell. 2000. Calcium signaling induced by adhesion mediates protein tyrosine phosphorylation and is independent of pHi. J. Cell. Physiol. 184:385-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wozniak, M. A., K. Modzelewska, L. Kwong, and P. J. Keely. 2004. Focal adhesion regulation of cell behavior. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1692:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu, W., J. L. Booth, K. M. Coggeshall, and J. P. Metcalf. 2006. Calcium-dependent viral internalization is required for adenovirus type 7 induction of IL-8 protein. Virology 355:18-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamamoto, D., Y. Sonoda, M. Hasegawa, M. Funakoshi-Tago, E. Aizu-Yokota, and T. Kasahara. 2003. FAK overexpression upregulates cyclin D3 and enhances cell proliferation via the PKC and PI3-kinase-Akt pathways. Cell. Signal. 15:575-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamshchikov, V. F., G. Wengler, A. A. Perelygin, M. A. Brinton, and R. W. Compans. 2001. An infectious clone of the West Nile flavivirus. Virology 281:294-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou, Y., T. K. Frey, and J. J. Yang. 2009. Viral calciomics: interplays between Ca2+ and virus. Cell Calcium 46:1-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]