Abstract

Mature vaccinia virus enters cells through either fluid-phase endocytosis/macropinocytosis or plasma membrane fusion. This may explain the wide range of host cell susceptibilities to vaccinia virus entry; however, it is not known how vaccinia virus chooses between these two pathways and which viral envelope proteins determine such processes. By screening several recombinant viruses and different strains, we found that mature virions containing the vaccinia virus A25 and A26 proteins entered HeLa cells preferentially through a bafilomycin-sensitive entry pathway, whereas virions lacking these two proteins entered through a bafilomycin-resistant pathway. To investigate whether the A25 and A26 proteins contribute to entry pathway specificity, two mutant vaccinia viruses, WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L, were subsequently generated from the wild-type WR strain. In contrast to the WR strain, both the WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L viruses became resistant to bafilomycin, suggesting that the removal of the A25 and A26 proteins bypassed the low-pH endosomal requirement for mature virion entry. Indeed, WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L virus infections of HeLa, CHO-K1, and L cells immediately triggered cell-to-cell fusion at a neutral pH at 1 to 2 h postinfection (p.i.), providing direct evidence that viral fusion machinery is readily activated after the removal of the A25 and A26 proteins to allow virus entry through the plasma membrane. In summary, our data support a model that on vaccinia mature virions, the viral A25 and A26 proteins are low-pH-sensitive fusion suppressors whose inactivation during the endocytic route results in viral and cell membrane fusion. Our results also suggest that during virion morphogenesis, the incorporation of the A25 and A26 proteins into mature virions may help restrain viral fusion activity until the time of infections.

Vaccinia virus has a wide host range and infects many cell lines in cultures and animal species (14). It belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus of the family Poxviridae and replicates in the cytoplasm of infected cells. Several unique features of vaccinia virus help to maximize its ability to transmit virus infections in different host cells. First, vaccinia virus produces several forms of infectious particles, including mature virus (MV), intracellular wrapped virus (WV), and extracellular enveloped virus (EEV) particles, that are suited for inter- or intrahost cell transmission and dissemination (8). Second, vaccinia virus MV attaches to cell surface components that are commonly expressed on cells. MV contains at least four attachment proteins, of which viral H3, A27, and D8 bind to cell surface glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) (7, 18, 24) and A26 binds to the extracellular matrix protein laminin (6). Third, MV enters cells through more than one route, since both endocytosis (9, 31) and plasma membrane fusion (1, 3, 4, 10, 12, 25, 39) were reported previously. The endocytosis of vaccinia virus MV is dependent on low pH (4.5 to 5.0) and sensitive to chemicals such as NaF, cytochalasin B (31), as well as bafilomycin A (BFLA), which blocks the acidification of endosomes (37). The exposure of MV to low pH in the range of pH 4.5 to 5.0 during infections forces the MV membrane to fuse with the plasma membrane, thus bypassing the need for endosomal acidification (37). The endocytic pathway of MV infections on HeLa cells was further characterized by Mercer et al. as dynamin-independent macropinocytosis (27) and by Huang et al. as a dynamin-dependent, vaccinia virus penetration factor (VPEF)-dependent, fluid-phase endocytosis (19). Although vaccinia virus MV is rich in phosphatidylserine (PS) (20), the reconstitution of the MV membrane with other lipids rescued virus infectivity, demonstrating that apoptotic mimicry (27) is not essential for MV entry (23). Finally, vaccinia virus MV entry pathways and signaling differed depending on cell types (3, 11, 25, 32, 34, 40) as well as virus strains (2, 28). These studies revealed a complex relationship of vaccinia virus MV entry processes with host cells.

Notwithstanding all the new advances in our understanding of vaccinia virus MV entry pathways, it remains unknown how MV controls cell entry through either the endocytic or plasma membrane route. In this study, we investigated this issue and identified viral envelope proteins that regulate virus entry pathway specificity.

(This work was conducted by S.-J.C. in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Ph.D. degree at Yang-Ming University, Taiwan, Republic of China, 2010.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

BSC40, HeLa, and L cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen). The Western Reserve (WR) strain of vaccinia virus was used as described previously (6). The IHD-J strain of vaccinia virus and the IA27L virus (33) were obtained from G. L. Smith. The IA27L virus contains an A27L open reading frame (ORF) under isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) regulation, so it was propagated in culture medium containing 5 mM IPTG (33). The IA27L virus contains a truncated A26L ORF, which was subsequently replaced by a full-length A26L(WR) ORF to generate a recombinant virus, IA27L-A26WR, also grown in IPTG as described previously (6). The IHD-W strain of vaccinia virus was purchased from the ATCC (ATCC 1441-VR). Wild-type WR, IHD-J, and IHD-W viruses expressing a dual-expression cassette, luc-lacZ (inserted at the tk locus), were subsequently generated with a luciferase (luc) gene driven by the viral early promoter and a lacZ gene by driven by the p11k late promoter. The purification of vaccinia virus MV was performed through a CsCl gradient as described previously (22). Vaccinia virus A25L(WR) ORF/WR148 encodes an A-type inclusion (ATI) protein of 725 amino acids (aa) that corresponds to the N-terminal fragment of the cowpox virus ATI protein (15, 29, 30). Herein, we refer to the vaccinia virus ATI protein as the A25 protein. Rabbit antisera recognizing the vaccinia virus A25 protein were generated by using a recombinant vaccinia virus A25 protein made with Escherichia coli as the antigen. Anti-A26, anti-A27, anti-D8, and anti-H3 antibodies (Abs) were described previously (6, 18, 24).

Construction of WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L viruses.

A dual-expression luc-gpt cassette containing the luciferase gene driven by a viral early promoter and the gpt gene driven by the p7.5k promoter was constructed. This dual-expression cassette was then individually cloned into plasmids that contained different flanking sequences to target A25L or A26L loci on the viral genome as described below. To construct a plasmid for generating the WRΔA25L virus, the luc-gpt cassette was cloned into plasmid pA24R/luc-gpt/A26L-KS(−) and flanked by A24R ORF and A26L ORF sequences isolated by PCR. The 1-kb flanking fragment containing the A24R promoter was generated by PCR using primers 5′-GCGGCCGCATGATTTTGCTAGAG-3′ and 5′-CTGCAGTTACACCAGAAAAGACGG-3′ (the NotI and PstI sites, respectively, are underlined). For the 1-kb flanking fragment containing the A26L promoter, the following primers were used: 5′-TGTAAGCAAATATTACAC-3′ and 5′-CTGCAGGTCGACTAATTATAAAATCGTAGA (the PstI site is underlined). Alternatively, to construct a plasmid for generating the WRΔA26L virus, the luc-gpt cassette was cloned into plasmid pA25L/luc-gpt/A27L-KS(−) and flanked by A25L ORF and A27L ORF sequences obtained by PCR. The 815-bp flanking fragment containing the A28/27L promoter was generated by PCR using primers 5′-ATTTTGTCAGCTTCTAAT-3′ and 5′-CTGCAGGTCGACAGAGTTAAGTTACTCATA-3′ (the PstI and SalI sites, respectively, are underlined). For the 620-bp flanking fragment of A24R, the following primers were used: 5′-CTGCAGTGTAGTTAAGTTTTGAAT-3′ and 5′-GCGGCCGCATTAATGTTAAGGAAGAG-3′ (the PstI and NotI sites, respectively, are underlined). The resulting plasmids were separately transfected into 293T cells that were subsequently infected with vaccinia virus (WR) and cultured for 2 to 3 days before cell harvesting. Recombinant WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L viruses were subsequently isolated by three rounds of plaque purification in 1% agar containing 25 μg/ml mycophenolic acid, 250 μg/ml xanthine, and 15 μg/ml hypoxanthine as described previously (21).

Virus entry assays.

Virus entry was determined by using virus core-uncoating assays (39) and luciferase assays (37) as previously described. In brief, HeLa cells were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or with 25 nM bafilomycin A (BFLA) for 30 min and subsequently infected with different vaccinia viruses at 37°C for 60 min. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), cells were incubated in growth medium with or without BFLA and harvested at 2 h postinfection (p.i.) for luciferase assays as described previously (37). Alternatively, infected HeLa cells were cultured in the presence of cycloheximide (30 μg/ml) for virus-uncoating analyses as described previously (39).

Cell fusion assays (fusion from without).

HeLa cells expressing red fluorescent protein (RFP) or green fluorescent protein (GFP) were mixed at a ratio of 1:1 and seeded into 96-well plates. Alternatively, GFP- or RFP-expressing L cells were used. On the following day cells were pretreated with 40 μg/ml cordycepin (Sigma) for 60 min and subsequently infected with wild-type (wt) WR, WRΔA25L, and WRΔA26L viruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 PFU per cell in triplicate. After infection at 37°C for 60 min, cells were washed once with PBS (pH 7.4) and photographed at 2 h p.i. by using a Zeiss Axiovert fluorescence microscope. For quantification of cell fusion, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (0.5 μg/ml). When CHO-K1 cells were used for cell fusion assays, additional plasma membrane staining was performed with a fluorescent lipid dye, PKH26 (Sigma), as described previously (5). Cell images were collected with an LSM510 Meta confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss) using a 40× objective lens and confocal microscopy software (release 2.8; Carl Zeiss), and nucleus numbers were counted from multiple images (>300 cells) as previously described (5). To quantify cell fusion, we calculated the percentage of fused cells as previously described (5). In brief, the percentage of cell fusion was calculated as follows: (sum of nuclei added from the fused cells/sum of nuclei added from total cells) × 100. We subdivided the above-described fused-cell population into three groups: small (2 to 10 nuclei/cell), medium (11 to 20 nuclei/cell), and large (>20 nuclei/cell) fused cell populations.

Peptide-blocking cell fusion assays.

Purified WRΔA26L MV were first incubated with either no peptide, a control peptide (LDTFGDVEQMQSFEQPKLKD), or an A26 peptide (441CCDTAAVDRLEHHIETLGQYAVILARKINMQT472) corresponding to the C-terminal coiled-coil region (aa 441 to 472) of the A26 protein (5) at a concentration of 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, or 2.0 mg/ml at 4°C for 60 min. The mixtures were subsequently put onto cordycepin-pretreated L cells for infections at an MOI of 50 PFU per cell at 37°C for 60 min, and cell fusion was determined at 2 h p.i. as described above. The peptides were present in the medium throughout the experiments.

Immunoblot analyses.

HeLa cells were infected with various viruses at an MOI of 5 PFU per cell for 1 h at 37°C and harvested at 24 h p.i. Cell lysates were separated on SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes for immunoblot analysis with anti-A25, anti-A26, anti-A27, anti-D8, and anti-H3 Abs.

RESULTS

Incorporation of the A25 and A26 proteins into MV particles converts the entry pathway of an IA27L mutant virus from plasma membrane fusion to endocytosis.

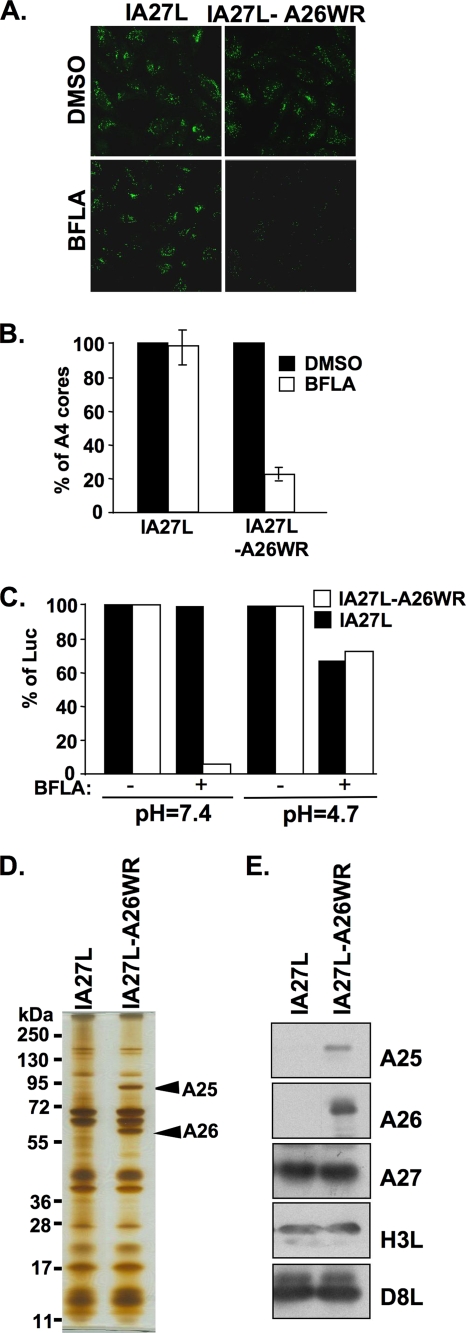

We tested two recombinant vaccinia viruses, IA27L and IA27L-A26WR, for their sensitivity to BFLA inhibition during entry into HeLa cells. The IA27L-A26WR virus was derived from the IA27L virus with an insertion of a full-length A26L ORF (WR strain) into the viral genome (5, 6). HeLa cells were pretreated with DMSO or 25 nM BFLA, infected with the IA27L or IA27L-A26WR virus at an MOI of 10 PFU per cell, and harvested for viral core-uncoating assays, in which anti-A4 Ab detected intracellular viral cores only after virus entry, as previously described (39). Immunofluorescence staining of viral cores showed that the viral uncoating of the IA27L virus was not affected by BFLA treatment, whereas the viral uncoating of the IA27L-A26WR virus was significantly reduced (Fig. 1A). Quantitative analysis of uncoated viral cores in the infected cells (Fig. 1B) suggests that, different from its parental IA27L virus, the entry of the IA27L-A26WR virus into HeLa cells occurs through a BFLA-sensitive, endocytic pathway. To confirm that the alteration of the BFLA sensitivity of IA27L-A26WR virus entry was due to endocytosis, we performed acid bypass experiments in which a brief exposure of cells to low pH during virus infections was utilized to trigger directly the fusion of cell-bound virions with the plasma membrane, thereby bypassing the endocytic route (37). HeLa cells were infected with the IA27L or IA27L-A26WR virus and briefly treated with neutral or acidic buffer (pH 4.7) for 3 min before cells were harvested at 2 h p.i. for early gene luciferase assays. The results showed that low-pH treatment indeed bypassed the endocytic pathway, changing IA27L-A26WR virus entry from a BFLA-sensitive to a BFLA-resistant manner (Fig. 1C). IA27L virus entry into HeLa cells was predominantly resistant to BFLA under both acidic and neutral conditions, consistent with virus entry through plasma membrane fusion.

FIG. 1.

BFLA sensitivity of IA27L and IA27L-A26WR viruses. (A) Immunofluorescence microscopy of virus-uncoating assays with HeLa cells pretreated with DMSO or 25 nM BFLA and infected with the IA27L or IA27L-A26WR virus. Anti-A4 Ab was used to stain uncoated viral cores. (B) Quantitative results of virus-uncoating assays shown in A. Viral core numbers in 30 cells were counted in each panel in A to obtain an average number of viral cores per cell. The viral core number obtained from cells treated with DMSO (−) was used as the 100% control. The percentage of A4 cores was calculated as follows: 100 × (viral core number per cell in BFLA-treated cells/viral core number per cell in DMSO-treated cells). The experiments were repeated three times, and the standard deviations are shown. (C) Acid bypass experiments with HeLa cells infected with the IA27L or IA27L-A26WR virus. HeLa cells were pretreated with DMSO (−) or with 25 nM BFLA (+) and subsequently infected with the IA27L or IA27L-A26WR virus at 4°C for 60 min. Cells were then treated with neutral (pH 7.4) or acidic (pH 4.7) buffer for 3 min, washed with PBS, and harvested for luciferase (Luc) assays at 2 h p.i. Luciferase activity obtained from cells treated with DMSO (−) was used as the 100% control. (D) Silver staining of SDS-PAGE gels containing 1 μg of purified IA27L and IA27L-A26WR MV particles. Arrows marked the A25 and A26 protein bands identified by mass spectrometry. (E) Immunoblot analyses of purified IA27L and IA27L-A26WR MV particles with anti-A25 (1:5,000), anti-A26 (1:1,000), anti-A27 (1:500), anti-H3 (1:1,000), and anti-D8 (1:1,000) Abs.

When MV of the IA27L and IA27L-A26WR viruses were purified and analyzed by SDS-PAGE with subsequent silver staining, we observed an extra protein of ∼90 kDa aside from the expected A26 protein in the IA27L-A26WR virus (Fig. 1D). The additional protein was identified by mass spectrometry as a vaccinia virus A-type inclusion (ATI) protein encoded by the A25L/WR148 ORF in the virus genome. Immunoblot analysis with anti-A25 Ab confirmed that the A25 protein was also incorporated into purified IA27L-A26WR virus MV particles (Fig. 1E). Therefore, these results imply that the addition of the A25 and A26 proteins on MV particles switches the virus entry pathway from plasma membrane fusion to an endocytic route.

Different entry pathways for vaccinia virus strains IHD-J and IHD-W correlate with the incorporation of viral A25 and A26 proteins on MV.

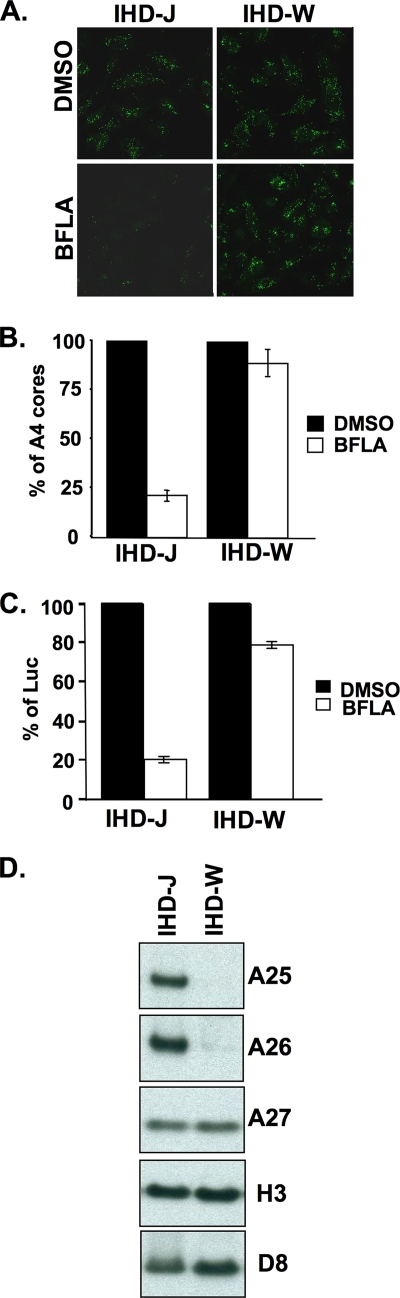

It was previously shown that different strains of vaccinia virus exhibit different sensitivities to BFLA (2). Therefore, we tested two vaccinia virus strains, IHD-J and IHD-W, to determine whether the A25 and A26 proteins contribute to such strain-specific differences of MV particles. HeLa cells were treated with DMSO or BFLA, subsequently infected with IHD-J or IHD-W at an MOI of 10 PFU/cell, and fixed at 2 h p.i. for virus entry assays. Immunofluorescence (Fig. 2A) and quantification of virus-uncoating assays (Fig. 2B) revealed that vaccinia virus MV entry of the IHD-J strain into HeLa cells was sensitive to BFLA, whereas the entry of the IHD-W strain was BFLA resistant. Data from viral early luciferase assays using recombinant IHD-J and IHD-W strains expressing the luciferase marker gene were consistent with this conclusion (Fig. 2C). Next, MV particles of IHD-J and IHD-W were purified for immunoblot analyses. As shown in Fig. 2D, the A25 and A26 proteins were detected on purified IHD-J but not on IHD-W particles. Thus, independent lines of evidence support the interesting conclusion that MV containing the A25 and A26 proteins enter HeLa cells through an endocytic route, whereas MV without these two proteins tend to fuse with the plasma membrane.

FIG. 2.

BFLA sensitivity of two vaccinia virus strains, IHD-J and IHD-W. (A) Immunofluorescence microscopy of virus-uncoating assays in HeLa cells pretreated with DMSO or 25 nM BFLA and infected with IHD-J or IHD-W. Anti-A4 Ab was used to stain uncoated viral cores. (B) Quantitative results of virus-uncoating assays shown in A. (C) Viral early luciferase assays of HeLa cells pretreated with DMSO or 25 nM BFLA, subsequently infected with IHD-J and IHD-W, and harvested at 2 h p.i. for luciferase assays. The viral luciferase activity of infected cells in the absence of BFLA (DMSO) was set to 100%. (D) Immunoblot analyses of purified IHD-J and IHD-W MV particles (1 μg) with anti-A25 (1:5,000), anti-A26 (1:1,000), anti-A27 (1:500), anti-H3 (1:1,000), and anti-D8 (1:1,000) Abs.

Generation of WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L deletion viruses from wild-type strain WR.

Our previous studies showed that the A26 protein binds to laminin (6). Although many studies reported the A-type inclusion bodies formed by the poxviral A25 protein in infected cells (see reference 8 and references therein), the question of whether the A25 protein plays a role in vaccinia virus entry has not been addressed. The preincubation of wild-type WR MV with anti-A25 Ab significantly reduced 80% of the plaque formation in cells (Fig. 3A), suggesting that anti-A25 Ab blocked MV infections. To investigate the role of the A25 protein in virus entry, we generated a mutant vaccinia virus, WRΔA25L, in which the vaccinia virus A25L ORF is deleted from the viral genome (Fig. 3B). In addition, we produced another recombinant virus, WRΔA26L, by deleting the A26L ORF from the viral genome (Fig. 3B). Immunoblot analyses of cell lysates harvested at 24 h p.i. showed that, indeed, neither the A25 nor the A26 protein was detected from cells infected with the corresponding mutant virus (Fig. 3C, left). Furthermore, the deletion of the A25L ORF from the viral genome did not significantly affect the expression of the A26 protein in infected cells and vice versa. When the purified WRΔA25L virus MV was analyzed, normal levels of A26 and several other envelope proteins, including the A27 and D8 proteins, were detected by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 3C, right). For the WRΔA26L virus, both the A25 and A26 proteins were absent in purified MV particles, showing that A25 protein incorporation into MV depends on the A26 protein, consistent with previous reports showing that the targeting of MV into ATI required the A26 protein (26). One-step growth curves did not show any difference in the growths of both the WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L viruses compared to the growth of wt WR, with MV titers increasing roughly 100-fold at 24 h p.i. (Fig. 3D). Levels of EEV production from wt WR, WRΔA25L, and WRΔA26L viruses were also not significantly different (Fig. 3E).

FIG. 3.

(A) Anti-A25 Ab blocked vaccinia virus plaque formation. BSC40 cells were infected with vaccinia virus wt strain WR in the presence of preimmune (1:100), anti-vaccinia virus MV (anti-VV) (1:100), or anti-A25 (1:100) Ab; washed; and overlaid with 1% agar. The plaques at 2 days p.i. were fixed and stained with 1% crystal violet before counting. (B) Schematic representation of vaccinia virus genomes containing ORFs A24R to A28L. Wild-type strain WR is shown on the top, with arrows pointing toward the direction of transcription. In WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L viruses, the viral A25L or A26L ORF was substituted with a dual-expression cassette, Luc-Gpt, containing a luciferase (Luc) gene driven by a viral early promoter and the Eco-Gpt (Gpt) gene driven by the viral p7.5 promoter. (C) Immunoblot analyses of A25 and A26 protein expressions in cells and on MV particles. HeLa cell lysates (Lysates) or purified MV particles (MV) were separated by SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-A25, anti-A26, anti-A27, and anti-D8 Abs. (D) One-step growth curve analyses of wild-type (WR) vaccinia virus and WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L mutant viruses. HeLa cells were infected at an MOI of 5 PFU per cell and harvested at 0, 2, 4, 8, 16, 24, and 48 h p.i. for plaque determination assays. (E) Extracellular virus titers were determined from culture medium collected from the infected cells shown in D. EEV titers were determined in the presence of anti-L1 MAb 2D5 (1:500) to block contaminating MV from forming plaques. The experiments were performed twice.

Entry of the WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L viruses into HeLa cells bypasses the endosomal requirement, becoming BFLA resistant.

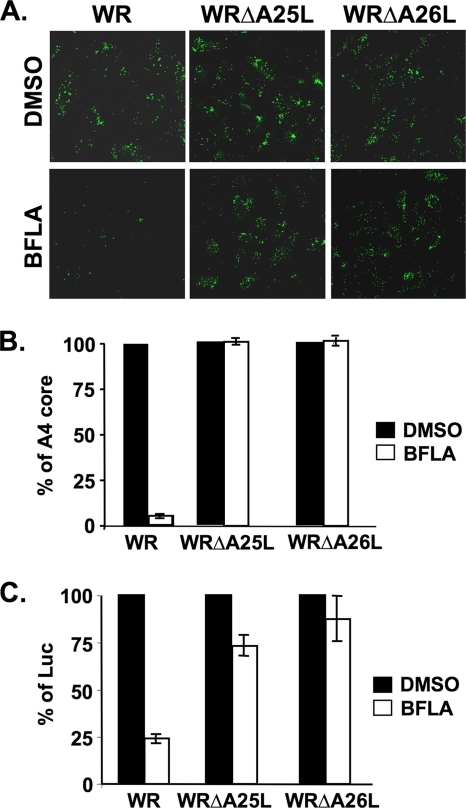

Although MV of the WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L viruses remained infectious, we tested whether these viruses actually enter cells through a different pathway. To this end, HeLa cells were pretreated with DMSO (control) or BFLA, subsequently infected with wt vaccinia virus (WR) or the WRΔA25L or WRΔA26L virus, and harvested at 2 h p.i. for virus-uncoating assays as previously described (39). Immunofluorescence staining of uncoated viral cores (Fig. 4A) and the resulting quantitative data (Fig. 4B) showed that the uncoating of viral cores in cells infected with wild-type virus (WR), but not with the WRΔA25L or WRΔA26L virus, was significantly inhibited by BFLA. Results obtained by viral early luciferase expression assays were consistent with the results of the uncoating assays (Fig. 4C). Apparently, both of these mutant viruses now employ a different entry pathway for infecting HeLa cells. As expected, acid bypass experiments showed that both the WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L viruses were resistant to BFLA at both neutral and acidic pHs (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

BFLA sensitivity of wild-type vaccinia virus strain WR and the WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L mutant viruses. (A) Immunofluorescence microscopy of virus-uncoating assays with HeLa cells pretreated with DMSO or 25 nM BFLA and infected with wild-type vaccinia virus WR and the WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L mutant viruses. Anti-A4 Ab was used to stain uncoated viral cores. (B) Quantitative results of virus-uncoating assays shown in A. (C) Viral early luciferase assays of HeLa cells pretreated with DMSO or 25 nM BFLA, subsequently infected with wild-type WR, WRΔA25L, and WRΔA26L viruses, and harvested at 2 h p.i. for luciferase assays. The viral luciferase activity of infected cells in the absence of BFLA (DMSO) was set to 100%.

A25 and A26 proteins mediate pH-sensitive suppression of virus-cell membrane fusion on HeLa, CHO-K1, and L cells.

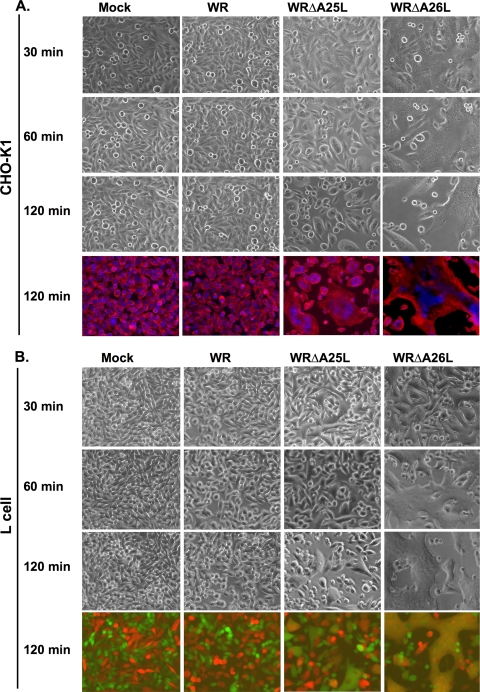

If the WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L viruses indeed enter HeLa cells through plasma membrane fusion, then an acidic environment should no longer be required for fusion activation. Accordingly, we examined whether HeLa cells infected with the WRΔA25L or WRΔA26L virus developed the cell fusion phenotype at a neutral pH. Cell fusion development was performed in the presence of cordycepin, which blocks viral early gene transcription, to verify that cell fusion at a neutral pH was triggered by incoming MV particles, i.e., cell fusion from without (FFWO). For the cell fusion assay, we cocultured HeLa cells expressing either GFP or RFP at a ratio of 1:1 so that if cell fusion occurs, the resulting fused cells could be detected as colocalized signals of GFP and RFP fluorescence (Fig. 5A). RFP- and GFP-expressing HeLa cells were infected with either wt WR, WRΔA25L, or WRΔA26L virus at an MOI of 50 PFU per cell at 37°C and subsequently photographed to monitor cell fusion. The images shown in Fig. 5A were photographed at 2 h p.i. During the whole 2-h period, HeLa cells infected with wt WR never developed cell fusion, as red and green cells remained small, with separate fluorescences (Fig. 5A, top row). HeLa cells infected with the WRΔA25L virus gradually developed cell fusion, and flat and large fused cells containing both fluorescent proteins were observed (Fig. 5A, middle row). Most strikingly, HeLa cells infected with the WRΔA26L strain developed robust cell fusion as early as 30 min p.i., and the extent of cell fusion was very substantial, resulting in a gigantic cell network formed by fused cells (Fig. 5A, bottom row). Cells were subsequently fixed, stained with DAPI, and photographed in order to quantify cell fusion as previously described (5). As quantified in Fig. 5B, the WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L viruses triggered significant cell fusion at a neutral pH, whereas wt WR did not, revealing that the A25 and A26 proteins function to suppress virus-cell fusion at a neutral pH. Since it has been repeatedly shown that wt WR triggered only FFWO on HeLa cells when treated with acidic buffer (pH 4.7) (Fig. 5C) (16, 24, 35, 36), we concluded that acid treatment most likely targeted the viral A25 and A26 proteins to relieve their suppressive effect, resulting in acid-induced cell FFWO. Our results also showed that although both the WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L viruses bypassed the low-pH requirement for virus entry, the intrinsic abilities to trigger FFWO between these two mutant viruses are somewhat different. The WRΔA26L virus, lacking both the A25 and A26 proteins, was more prone to fusion than was the WRΔA25L virus, which still contains the A26 protein, suggesting that the removal of the A26 protein from MV is the rate-limiting step to optimize virus-cell membrane fusion at a neutral pH. Similar to HeLa cells, the WRΔA26L virus induced faster and more extensive cell fusion than did the WRΔA25L virus on CHO-K1 (Fig. 6A) and L (Fig. 6B) cells at a neutral pH.

FIG. 5.

Cell fusion from without at neutral pH on HeLa cells triggered by MV of WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L viruses but not by wt WR. (A) RFP- and GFP-expressing HeLa cells were mixed at a ratio of 1:1 during cell seeding. These cells were infected with purified wt WR, WRΔA25L, and WRΔA26L viruses at an MOI of 100 PFU per cell at 37°C for 60 min at a neutral pH as described in Materials and Methods, fixed at 2 h p.i., and photographed. Merge, red, and green immunofluorescence images were overlays with cell morphology. (B) Quantification of cell fusion from without (A), as described in Materials and Methods. Percentages of cell fusion were quantified into four different categories based on the numbers of cell nuclei per cell (1, 2 to 10, 11 to 20, or >20 nuclei/cell). (C) Wild-type WR MV triggered cell fusion from without only after low-pH (pH 4.7) treatment. GFP- and RFP-expressing HeLa cells were infected with wild-type WR as described above (A) and treated briefly with low-pH buffer (pH 4.7) for 3 min, and cell fusion was developed and photographed at 2 h p.i.

FIG. 6.

Kinetic analyses of cell fusion from without at neutral pH on CHO-K1 and L cells triggered by MV of WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L viruses but not by wt WR. (A) CHO-K1 cells were infected with WR, WRΔA25L, and WRΔA26L viruses at an MOI of 100 PFU per cell at 37°C for 60 min at a neutral pH as described in the legend of Fig. 5A. Cells were photographed at 30, 60, and 120 min p.i. to monitor the occurrence of flat fused cells. At the end of the experiment (120 min p.i.), cells were fixed, and nuclei were stained with DAPI (0.5 μg/ml). The plasma membrane was stained with a fluorescent dye, PKH26, to visualize cell shapes. (B) RFP- and GFP-expressing L cells were cocultured and infected with wt WR, WRΔA25L, and WRΔA26L viruses at a neutral pH as described above. Cells were photographed at 30, 60, and 120 min p.i. to monitor the occurrence of flat fused cells. At the end of the experiment (120 min p.i.), cells were fixed for photography, and merged images of red and green immunofluorescence are shown. Yellow images represent areas of fused cells.

It is worth noting that neither the A25 nor the A26 protein is an integral membrane protein and needs to interact with an additional viral envelope protein to be incorporated into MV particles. Since we previously showed that the A26 protein formed disulfide bonds with the A27 protein through cysteine residues 441 and 442 at the C-terminal coiled-coil region (5), it is conceivable that the A26-A27 protein complex formation provided a means for tagging the A25 protein onto the MV surface. However, we considered that the role of the A26 protein in cell fusion suppression is more than maintaining the A25 protein on MV (see below). A synthetic A26 peptide containing the C-terminal coiled-coil region of the A26 protein from aa 441 to 472, but not a control peptide, partially inhibited cell fusion induced by WRΔA26L virus infections of L cells in a dosage-dependent manner (Fig. 7), implying that the A26 protein could inactivate viral fusion activity through modulating the coiled-coil interaction with the A27 protein even in the absence of the A25 protein.

FIG. 7.

Peptide-blocking cell fusion assays. RFP- and GFP-expressing L cells were mock infected or infected with WRΔA26L virus with or without peptides at different concentrations (0.1, 0.5, 1.0, or 2.0 mg/ml), as described in Materials and Methods, and photographed at 2 h p.i. The A26 peptide corresponds to the C-terminal coiled-coil region (aa 441 to 472) of the A26 protein. Another peptide with no homology with A26 amino acid sequences was included as the control. Merged images of red and green immunofluorescence are shown. Yellow images represent areas of fused cells.

A25 and A26 proteins of MV control strain-specific variations of vaccinia virus entry pathways.

Finally, based on the DNA sequences provided by the Poxvirus Bioinformatics Resource Center (http://www.poxvirus.org/), we looked for additional vaccinia virus strains that have deleted or mutated A25L and A26L ORFs and found that the MVA strain expressed no A25 protein and a truncated version of the A26 protein of 227 aa. We also obtained a vaccinia virus mutant, VV-hr (13), that was derived from the Copenhagen strain, which also contains truncated A25 and A26 ORFs. MV particles of both the MVA and VV-hr strains were purified and indeed contained no A25 and A26 proteins (Fig. 8A). We thus tested vaccinia virus strain MVA along with strains VV-hr, IHD-J, and IHD-W in our FFWO assays using GFP- and RFP-expressing HeLa cells at a neutral pH, and all strains except IHD-J induced HeLa cell fusion at a neutral pH (Fig. 8B). All the vaccinia virus strains that we tested are listed in Table 1, and the results consistently showed that the presence of the A25 and A26 proteins on MV suppressed cell fusion at a neutral pH.

FIG. 8.

Vaccinia virus strains MVA and Copenhagen lacking intact A25 and A26 proteins triggered cell fusion at neutral pH. (A) Immunoblots of purified MV from strains WR, VV-hr (Copenhagen strain), and MVA with Abs recognizing viral A25, A26, A27, and H3 proteins. (B) Cell fusion assays at 2 h p.i. after infections with strains IHD-J, IHD-W, VV-hr (Copenhagen), and MVA. Merged images of red and green immunofluorescence are shown. Yellow images representing areas of fused cells were observed for all strains except IHD-J.

TABLE 1.

pH-dependent cell fusion activities of different vaccinia virus strainsa

| Virus strain | Presence of protein |

Sensitivity to BFLA | Presence of FFWO (pH) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A25 | A26 | |||

| wt WR | + | + | Sensitive | + (4.7) |

| IHD-J | + | + | Sensitive | + (4.7) |

| IHD-W | − | − | Resistant | + (7.4) |

| MVA | − | − | Resistant | + (7.4) |

| VV-hr (Copenhagen) | − | − | Resistant | + (7.4) |

Vaccinia virus strains such as wt WR and IHD-J contain the A25 and A26 proteins on MV particles, are sensitive to BFLA, and trigger cell fusion at a low pH (pH 4.7). Other virus strains such as IHD-W, MVA, and VV-hr (from Copenhagen) lacked the A25 and A26 proteins on MV particles, are resistant to BFLA, and fuse at a neutral pH (pH 7.4).

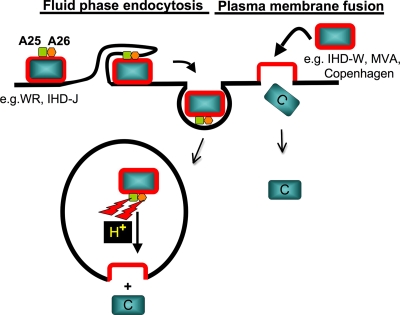

In summary, based on our data, we propose a model (Fig. 9) in which the viral A25 and A26 proteins function as cell fusion suppressors for MV particles. Wild-type MV strains containing the A25 and A26 proteins, such as WR and IHD-J, are not prone to fusion at a neutral pH. Such MV particles are internalized into acidic endosomal environments, which somehow nullify the fusion suppressor activity of the A25 and A26 proteins, leading to viral membrane fusion with endosomal membranes. In contrast, MV of vaccinia virus strains lacking the A25 and A26 proteins, such as IHD-W, MVA, and Copenhagen, do not require low pH and thus enter HeLa cells through fusion with the plasma membrane. Although our current model may appear oversimplified, it does not exclude the contributions of the A25 and A26 proteins in other virus entry steps such as specific cell surface receptor usage and/or intracellular signaling regulation.

FIG. 9.

Working model of vaccinia virus entry pathways controlled by viral A25 and A26 proteins. We propose that viral A25 and A26 proteins function as cell fusion suppressors for vaccinia virus MV particles. Vaccinia virus strains WR and IHD-J contain the A25 and A26 proteins to suppress viral fusion with the plasma membrane of cells. These MV are internalized into intracellular vesicles, of which the acidic environments (H+) nullify the fusion suppressor activity of the A25 and A26 proteins, leading to viral membrane fusion with endosomal membranes to release viral cores into the cytoplasm. In contrast, MV of vaccinia virus strains lacking the A25 and A26 proteins, such as strains IHD-W, MVA, and Copenhagen, enter HeLa cells through fusion with the plasma membrane in neutral-pH environments. C, viral core.

DISCUSSION

Vaccinia virus MV either fuse with the plasma membrane or are internalized by endocytosis and subsequent fusion with the endosomal membrane during virus entry into host cells. Cell type-specific and virus strain-specific differences have been observed; however, the molecular basis driving such differences is not known. Here, we demonstrate that the MV A25 and A26 proteins contribute to such strain-specific differences for vaccinia virus MV entry into HeLa, CHO-K1, and L cells. Initially, we observed a difference in the sensitivities of recombinant IA27L and IA27L-A26WR viruses to BFLA inhibition during entry into HeLa cells. These results encouraged us to extend our study to a comparison between the IHD-J and IHD-W strains. These two pairs of comparison provided independent but correlative data, which prompted us to look further into the role of both the A25 and A26 proteins in vaccinia virus entry pathway specificity. Because the IA27L virus and strains IHD-J and IHD-W are not well characterized and sequenced, which makes them inconvenient for the construction of deletion mutants, we proceeded to employ the standard wt WR strain in subsequent experiments. Thus, we generated WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L mutant viruses from the wt WR genome. It is worth noting that the phenotype of WRΔA26L MV particles is actually equivalent to a WRΔA25LΔA26L double mutant, since the A25 protein is not packaged without the A26 protein. As expected on the basis of our above-described results, both mutant viruses were indeed different from wt WR, becoming resistant to BFLA.

It was previously shown that BFLA sensitivity dictates vaccinia virus endocytosis, whereas BFLA resistance reflects virus entry through the plasma membrane fusion route (36). It is thus satisfying to observe that WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L virus infections of HeLa cells indeed triggered a cell fusion phenotype at a neutral pH, suggesting that the A25 and A26 proteins on wild-type WR MV actually suppressed virus-cell fusion at the plasma membrane. The fact that acid treatment of wild-type WR MV can force virus entry through the plasma membrane (37) reinforces the idea that acid treatment inactivates the suppressor functions of the A25 and A26 proteins, mimicking our WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L deletion mutants. This idea provides a potential mechanism to explain wild-type WR virus entry through an endocytic route since the low pH of endosomal compartments may similarly nullify the suppressor activity of the A25 and A26 proteins so that fusion between viral and endosomal membranes could occur. Our current working model is shown in Fig. 9 and is supported by cell fusion experiments with other vaccinia virus strains such as IHD-J, IHD-W, MVA, and VV-hr of the Copenhagen strain. Currently, we do not have the molecular details to explain how the A25 and A26 proteins suppressed cell fusion, although the peptide-blocking experiments suggested that an association between the A26 and A27 proteins may play a key role in such a regulation. In the future, more experiments will be performed to validate our model.

The vaccinia virus A25 protein was reported previously to be present on MV (38), but the role of the A25 protein in vaccinia virus MV entry was not investigated. Cowpox and ectromelia viruses encode much larger A25 orthologues of 160 kDa in size, which form aggregates at intracellular sites to store MV particles in virus-infected cells (15, 26, 30, 31). In contrast, although the vaccinia virus A25/WR148 protein, which contains 725 aa and represents the N-terminal fragment of the cowpox virus ATI protein, still formed small inclusions in the infected cells, it failed to recruit vaccinia virus MV into the inclusions in the infected cells (26). Although puzzling to researchers, the conservation of this ∼700-aa ATI fragment in multiple poxviruses suggests that this truncated protein fragment has some functions in the virus life cycle. Our conclusion that the A25 protein functions in conjunction with the A26 protein to suppress viral fusion activity argued that such a conservation is of biological significance. First of all, during virion morphogenesis, the A25 and A26 proteins on MV keep viral fusion activity in check so that premature fusion does not happen among MV particles to reserve virion infectivity. Interestingly, Ulaeto et al. previously proposed that the presence of A26 proteins on MV targeted virions to inclusion bodies, whereas a lack of the A26 protein on MV signals the secondary wrapping of MV to become an EEV (38). In this regard, the fact that the A25 and A26 proteins function as fusion suppressors could add weight to the proposal by those authors in that MV embedded in ATI are well protected from fusion activation, whereas MV wrapped inside an EEV mimics the WRΔA26L virus and could directly fuse with the plasma membrane of host cells after EEV membrane rupture. Moreover, our model is also consistent with the fact that the deletion of the A26L ORF does not necessarily decrease EEV titers (5, 6, 17), whose production was not kinetically regulated by the A26 protein. Finally, the presence of A25 and A26 on MV represents a viral strategy to modulate virus entry through an endocytic pathway, in which fusion is controlled by low pH through the inactivation of fusion suppression functions of the A25 and A26 proteins.

Although our results explained, to some extent, the strain specificity with regard to the vaccinia virus entry pathway, we do not exclude influences of other factors on virus-induced cell fusion. We have not exhausted our searches of different poxviruses to verify our model yet and will continue to do so in the future. Furthermore, this study did not address the cell type-specific influence on virus entry pathways, as indicated by previous studies (40). In our hands, virus-induced cell fusion in CHO-K1 and L cells is regulated similarly to HeLa cells. One reason for this similarity could be cell surface glycosaminoglycans, which we have previously found to be necessary for the occurrence of virus-induced cell fusion on L cells (5). In contrast, infections of WRΔA25L and WRΔA26L viruses remained partially sensitive to BFLA in primary BSC40 cells and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), and no obvious FFWO was observed at a neutral pH either (data not shown), suggesting an additional cell type-specific control of the vaccinia virus membrane fusion mechanism. It is worth noting that although we propose a fusion suppressor model (depicted in Fig. 9), an alternative modification remains possible in which the A25 and A26 proteins may bind to a cell type-specific receptor that is engaged in a downstream fusion event. Clearly, many questions remain to be answered, and further investigations are needed to dissect further steps in the regulation of vaccinia virus entry and membrane fusion.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shiaw-Ming Hwang for providing HUVECs and Der-Lii Tzou for providing synthetic peptides. We also thank D. J. Pickup for reading the manuscript and helpful comments.

This work was supported by grants from the Academia Sinica and the National Science Council of the Republic of China (NSC97-2320-B-001-001MY3).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 June 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong, J. A., D. H. Metz, and M. R. Young. 1973. The mode of entry of vaccinia virus into L cells. J. Gen. Virol. 21:533-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bengali, Z., A. C. Townsley, and B. Moss. 2009. Vaccinia virus strain differences in cell attachment and entry. Virology 389:132-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter, G. C., M. Law, M. Hollinshead, and G. L. Smith. 2005. Entry of the vaccinia virus intracellular mature virion and its interactions with glycosaminoglycans. J. Gen. Virol. 86:1279-1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang, A., and D. H. Metz. 1976. Further investigations on the mode of entry of vaccinia virus into cells. J. Gen. Virol. 32:275-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ching, Y. C., C. S. Chung, C. Y. Huang, Y. Hsia, Y. L. Tang, and W. Chang. 2009. Disulfide bond formation at the C termini of vaccinia virus A26 and A27 proteins does not require viral redox enzymes and suppresses glycosaminoglycan-mediated cell fusion. J. Virol. 83:6464-6476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiu, W. L., C. L. Lin, M. H. Yang, D. L. Tzou, and W. Chang. 2007. Vaccinia virus 4c (A26L) protein on intracellular mature virus binds to the extracellular cellular matrix laminin. J. Virol. 81:2149-2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung, C. S., J. C. Hsiao, Y. S. Chang, and W. Chang. 1998. A27L protein mediates vaccinia virus interaction with cell surface heparan sulfate. J. Virol. 72:1577-1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Condit, R. C., N. Moussatche, and P. Traktman. 2006. In a nutshell: structure and assembly of the vaccinia virion. Adv. Virus Res. 66:31-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dales, S., and R. Kajioka. 1964. The cycle of multiplication of vaccinia virus in Earle's strain L cells. I. Uptake and penetration. Virology 24:278-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dallo, S., J. F. Rodriguez, and M. Esteban. 1987. A 14K envelope protein of vaccinia virus with an important role in virus-host cell interactions is altered during virus persistence and determines the plaque size phenotype of the virus. Virology 159:423-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Magalhaes, J. C., A. A. Andrade, P. N. Silva, L. P. Sousa, C. Ropert, P. C. Ferreira, E. G. Kroon, R. T. Gazzinelli, and C. A. Bonjardim. 2001. A mitogenic signal triggered at an early stage of vaccinia virus infection: implication of MEK/ERK and protein kinase A in virus multiplication. J. Biol. Chem. 276:38353-38360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doms, R. W., R. Blumenthal, and B. Moss. 1990. Fusion of intra- and extracellular forms of vaccinia virus with the cell membrane. J. Virol. 64:4884-4892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drillien, R., F. Koehren, and A. Kirn. 1981. Host range deletion mutant of vaccinia virus defective in human cells. Virology 111:488-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenner, F. 1990. Poxviruses, p. 2113-2133. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, et al. (ed.), Fields virology. Raven Press, New York, NY.

- 15.Funahashi, S., T. Sato, and H. Shida. 1988. Cloning and characterization of the gene encoding the major protein of the A-type inclusion body of cowpox virus. J. Gen. Virol. 69(Pt. 1):35-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong, S. C., C. F. Lai, and M. Esteban. 1990. Vaccinia virus induces cell fusion at acid pH and this activity is mediated by the N-terminus of the 14-kDa virus envelope protein. Virology 178:81-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howard, A. R., T. G. Senkevich, and B. Moss. 2008. Vaccinia virus A26 and A27 proteins form a stable complex tethered to mature virions by association with the A17 transmembrane protein. J. Virol. 82:12384-12391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsiao, J.-C., C.-S. Chung, and W. Chang. 1999. Vaccinia virus envelope D8L protein binds to cell surface chondroitin sulfate and mediates the adsorption of intracellular mature virions to cells. J. Virol. 73:8750-8761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang, C. Y., T. Y. Lu, C. H. Bair, Y. S. Chang, J. K. Jwo, and W. Chang. 2008. A novel cellular protein, VPEF, facilitates vaccinia virus penetration into HeLa cells through fluid phase endocytosis. J. Virol. 82:7988-7999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ichihashi, Y., and M. Oie. 1983. The activation of vaccinia virus infectivity by the transfer of phosphatidylserine from the plasma membrane. Virology 130:306-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Izmailyan, R. A., C. Y. Huang, S. Mohammad, S. N. Isaacs, and W. Chang. 2006. The envelope G3L protein is essential for entry of vaccinia virus into host cells. J. Virol. 80:8402-8410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joklik, W. K. 1962. The purification of four strains of poxvirus. Virology 18:9-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laliberte, J. P., and B. Moss. 2009. Appraising the apoptotic mimicry model and the role of phospholipids for poxvirus entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:17517-17521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin, C. L., C. S. Chung, H. G. Heine, and W. Chang. 2000. Vaccinia virus envelope H3L protein binds to cell surface heparan sulfate and is important for intracellular mature virion morphogenesis and virus infection in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 74:3353-3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Locker, J. K., A. Kuehn, S. Schleich, G. Rutter, H. Hohenberg, R. Wepf, and G. Griffiths. 2000. Entry of the two infectious forms of vaccinia virus at the plasma membrane is signaling-dependent for the IMV but not the EEV. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:2497-2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKelvey, T. A., S. C. Andrews, S. E. Miller, C. A. Ray, and D. J. Pickup. 2002. Identification of the orthopoxvirus p4c gene, which encodes a structural protein that directs intracellular mature virus particles into A-type inclusions. J. Virol. 76:11216-11225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mercer, J., and A. Helenius. 2008. Vaccinia virus uses macropinocytosis and apoptotic mimicry to enter host cells. Science 320:531-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mercer, J., S. Knebel, F. I. Schmidt, J. Crouse, C. Burkard, and A. Helenius. 2010. Vaccinia virus strains use distinct forms of macropinocytosis for host-cell entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:9346-9351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okeke, M. I., O. A. Adekoya, U. Moens, M. Tryland, T. Traavik, and O. Nilssen. 2009. Comparative sequence analysis of A-type inclusion (ATI) and P4c proteins of orthopoxviruses that produce typical and atypical ATI phenotypes. Virus Genes 39:200-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel, D. D., D. J. Pickup, and W. K. Joklik. 1986. Isolation of cowpox virus A-type inclusions and characterization of their major protein component. Virology 149:174-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Payne, L. 1978. Polypeptide composition of extracellular enveloped vaccinia virus. J. Virol. 27:28-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahbar, R., T. T. Murooka, A. A. Hinek, C. L. Galligan, A. Sassano, C. Yu, K. Srivastava, L. C. Platanias, and E. N. Fish. 2006. Vaccinia virus activation of CCR5 invokes tyrosine phosphorylation signaling events that support virus replication. J. Virol. 80:7245-7259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez, J. F., and G. L. Smith. 1990. IPTG-dependent vaccinia virus: identification of a virus protein enabling virion envelopment by Golgi membrane and egress. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:5347-5351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandgren, K. J., J. Wilkinson, M. Miranda-Saksena, G. M. McInerney, K. Byth-Wilson, P. J. Robinson, and A. L. Cunningham. 2010. A differential role for macropinocytosis in mediating entry of the two forms of vaccinia virus into dendritic cells. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senkevich, T. G., and B. Moss. 2005. Vaccinia virus H2 protein is an essential component of a complex involved in virus entry and cell-cell fusion. J. Virol. 79:4744-4754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Townsley, A. C., and B. Moss. 2007. Two distinct low-pH steps promote entry of vaccinia virus. J. Virol. 81:8613-8620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Townsley, A. C., A. S. Weisberg, T. R. Wagenaar, and B. Moss. 2006. Vaccinia virus entry into cells via a low-pH-dependent endosomal pathway. J. Virol. 80:8899-8908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ulaeto, D., D. Grosenbach, and D. E. Hruby. 1996. The vaccinia virus 4c and A-type inclusion proteins are specific markers for the intracellular mature virus particle. J. Virol. 70:3372-3377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vanderplasschen, A., M. Hollinshead, and G. L. Smith. 1998. Intracellular and extracellular vaccinia virions enter cells by different mechanisms. J. Gen. Virol. 79(Pt. 4):877-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whitbeck, J. C., C. H. Foo, M. Ponce de Leon, R. J. Eisenberg, and G. H. Cohen. 2009. Vaccinia virus exhibits cell-type-dependent entry characteristics. Virology 385:383-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]