Abstract

The ways in which human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) major immediate-early (MIE) gene expression breaks silence from latency to initiate the viral replicative cycle are poorly understood. A delineation of the signaling cascades that desilence the HCMV MIE genes during viral quiescence in the human pluripotent N-Tera2 (NT2) cell model provides insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying HCMV reactivation. In this model, we show that phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) immediately activates the expression of HCMV MIE RNA and protein and greatly increases the MIE-positive (MIE+) NT2 cell population density; levels of Oct4 (pluripotent cell marker) and HCMV genome penetration are unchanged. Decreasing PKC-delta activity (pharmacological, dominant-negative, or RNA interference [RNAi] method) attenuates PMA-activated MIE gene expression. MIE gene activation coincides with PKC-delta Thr505 phosphorylation. Mutations in MIE enhancer binding sites for either CREB (cyclic AMP [cAMP] response element [CRE]) or NF-κB (κB) partially block PMA-activated MIE gene expression; the ETS binding site is negligibly involved, and κB does not confer MIE gene activation by vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP). The PMA response is also partially attenuated by the RNAi-mediated depletion of the CREB or NF-κB subunit RelA or p50; it is not diminished by TORC2 knockdown or accompanied by TORC2 dephosphorylation. Mutations in both CRE and κB fully abolish PMA-activated MIE gene expression. Thus, PMA stimulates a PKC-delta-dependent, TORC2-independent signaling cascade that acts through cellular CREB and NF-κB, as well as their cognate binding sites in the MIE enhancer, to immediately desilence HCMV MIE genes. This signaling cascade is distinctly different from that elicited by VIP.

Novel strategies to mitigate the disease burden resulting from human cytomegalovirus (CMV) (HCMV) reactivation are needed. Knowledge about the ways in which HCMV major immediate-early (MIE) gene expression breaks silence from latency to start the viral replicative cycle has the potential to inform the development of new therapies to preempt viral replication. However, the molecular mechanisms that regulate the switch from HCMV MIE gene silence to activation are poorly understood.

The expression of viral MIE genes is required to initiate the productive life cycles of human and animal CMV species, whereas expression is greatly restricted or absent during the latency of these viruses (39, 52, 53, 57). The 550-bp MIE enhancer is the vital regulatory center for the transcriptional activation of the MIE gene locus (39). The enhancer's function is attributed to assorted cis-acting elements that are consensus binding sites for different specific cellular transcription factors (9, 22, 31, 37); several types of cis-acting elements are repeated. Signaling networks relay and integrate information from the cell, the virus, and the extracellular environment to dynamically modulate the functional activities of these cellular transcription factors (9, 24). The composite configuration of the specific cis-acting elements in the HCMV MIE enhancer differs greatly from that of evolutionarily distant cytomegalovirus relatives (39). This may explain why the replacement of this enhancer with the MIE enhancer from murine CMV (MCMV) renders HCMV poorly competent at executing both MIE gene expression and viral genome replication in lytically infected cells (21).

HCMV infection of human pluripotent embryonal NTera2/D1 (NT2) cells is a tractable model with which to molecularly characterize the regulatory mechanisms that break HCMV MIE gene expression silence in a setting of viral quiescence (25, 36). These cells become either neurons and astrocytes after treatment with retinoic acid (RA) (2, 3) or epithelial and smooth muscle-like cells after treatment with bone morphogenetic protein 2 (10). Keeping NT2 cells in an undifferentiated state, partly by propagation under progenitor cell growth conditions (36), promotes quiescent HCMV infection and results in greater than 98% of NT2 nuclei containing HCMV pp65 at 1 h postinfection (p.i.) with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 3 to 5 (25) and approximately 3 HCMV genome equivalents per nucleus at 24 h p.i. with an MOI of 10 (38). At 48 h p.i., the NT2 cells contain a subset of nonreplicating HCMV genomes having a DNA structure of covalently closed circles with superhelical twists (36).

In infected NT2 cells, either the histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) (36) or the stimulation of cyclic AMP (cAMP)-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) activity (25, 59) immediately turns on the transcription of HCMV MIE genes in previously dormant HCMV genomes (25, 59). This rapidly induced transcriptional activation is not the result of cellular differentiation (42, 59). Conversely, RA fails to reverse the MIE enhancer/promoter silence in quiescently infected NT2 cells (36), but its use to first convert these cells into differentiated NT2 (NT2-D) cells subsequently enables the activation of the HCMV MIE enhancer/promoter immediately upon viral infection (16). In a similar NT2 cell model, the inhibition of HDAC by TSA was found to disrupt heterochromatin nucleation at the MIE enhancer/promoter (42), akin to the chromatin disruption that accompanies HCMV reactivation in endogenously infected dendritic cells (49). We have shown recently with NT2 cells that the stimulation of the cAMP-PKA-CREB signaling cascade by either vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) or forskolin (FSK) activates the HCMV MIE enhancer/promoter via cAMP response elements (CREs) to relieve HCMV genome silence (25, 59). The transcriptional coactivator transducer of regulated CREB-2 (TORC2) is a critical part of this signaling pathway and must also be activated by VIP or FSK via a PKA-dependent mechanism in order to desilence the MIE genes (59).

Ancillary data coming from recent work sparked an awareness of phorbol ester's ability to also increase HCMV MIE gene expression levels in quiescently infected NT2 cells (59). This invited speculation that MIE gene activation might be achieved as well through a separate regulatory pathway that involves protein kinase C (PKC) (59). Phorbol esters are diacylglycerol (DAG) mimics that directly bind to and activate the PKC isoforms belonging to the conventional (alpha, beta, and gamma) and novel (delta, epsilon, theta, and nano) subgroups, designated the cPKC and nPKC subgroups, respectively. Phorbol ester also directly targets chimerins, protein kinase D, RasGRPs, Munc13s, and DAG kinase gamma (7). These actions then activate a specific assortment of signaling cascades and target genes that vary in accordance with cell types and growth conditions. NT2 cells are known to contain PKC-alpha, -beta, and -delta isoforms (1, 23, 29, 44, 45, 47), and PKC-alpha, -beta, -gamma, and -epsilon increase in abundance with NT2 cell differentiation (1, 29, 44, 47). A novel PKC-deltaVIII isoform made from a PKC-delta RNA splice variant is upregulated in differentiated NT2 cells and has antiapoptotic functions (23). Thus, the possibility exists that phorbol ester could act directly on any one of a number of different proteins to override HCMV MIE silence in NT2 cells.

One previous report indicated that phorbol ester treatment of NT2 cells increases AP1 target gene expression in transient assays but fails to stimulate NT2 cell differentiation unless combined with RA (29). In other cell types, phorbol ester was shown to differentially activate genes through any one or a combination of different specific cellular transcription factors, including AP-1, CREB, ETS, SRF, NF-κB, and SP1 family members, which function in manners that depend on the target gene and cell type. Because the HCMV MIE enhancer contains cognate sites for several members of this transcription factor panoply (e.g., AP-1, CREB, ETS, SRF, NF-κB, and SP1) (39), multiple possibilities underlie an investigation into the mechanisms by which the MIE genes are desilenced in quiescently infected NT2 cells.

In this report, we show that phorbol ester stimulation of quiescently infected NT2 cells immediately activates HCMV MIE gene expression through a signaling cascade that involves cellular PKC-delta, CREB, and NF-κB. This response is conveyed by the CRE and NF-κB binding sites (κB) located in the HCMV MIE enhancer. Phorbol ester does not change NT2 cell pluripotent status or viral genome penetration during the time frame in which stimulation activates MIE gene expression.

(This work was presented in part at the 34th International Herpesvirus Workshop in Ithaca, NY.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Human NTera2/D1 (NT2) cells (16) were grown as described previously (36) to minimize background levels of NT2 cell differentiation and HCMV MIE expression (36, 59). Knockout Serum Replacement medium contains insulin and was temporarily removed from medium when examining the effects of the indicated stimuli. The addition of 10 μM retinoic acid (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for ≥7 days produced differentiated NT2 cells. This medium was replaced with NT2 growth medium at least 1 day prior to performing experiments. Human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) were isolated and grown as described previously (38).

HCMV strain Towne was used throughout these studies. HCMV-GFP (Towne strain) represents rΔ−640/−1108gfp (33), which contains the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene driven by the viral native UL127 promoter that is expressed with early/late kinetics. HCMV used in NT2 cell experiments was partially purified by the centrifugation of filtered (0.45-μm filter) cell-free virus through a 20% sorbitol cushion in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The viral pellet was resuspended in DMEM or RPMI medium without serum. Virus absorption was carried out for 60 to 90 min, and infected cells were subsequently washed twice or three times with Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) without calcium and magnesium.

Recombinant HCMVs were constructed from an HCMV Towne strain BACmid that was a gift from Feng Liu (15). The modulator segment (base positions −640 to −1108) was replaced with the kanamycin resistance gene to enable the selection of BACmid recombinants in Escherichia coli cells. Wild-type (WT) recombinant (rWT) HCMV represents the Towne BACmid containing the wild-type MIE enhancer plus the kanamycin resistance gene in place of the modulator. Each of five copies of CRE in rCRE5M (rCRE−) and rCRE5METS1M (rCRE−.ETS−) (base positions −94, −157, −262, and −413 relative to the +1 transcription start site) contains the same two-base substitution mutations that were reported previously by Keller et al. (24) to eliminate MIE CRE activity in the otherwise normal HCMV Towne genome. The ETS binding sequence at base position −538 in the HCMV MIE enhancer/promoter was changed from GTTCCGC to GTgaaGC in both rETS1M (rETS−) and rCRE−.ETS−, based on the findings described previously by Chan et al. (11) that reveal that these three-base substitutions in the comparable element of simian CMV eliminate phorbol ester-induced MIE enhancer/promoter responsiveness in transient assays. The base substitutions placed into each of the κB elements (base positions −58, −131, −317, −400, and −453 relative to the +1 transcription start site) of rκB4 M (rκB−) are the same as those reported previously by Caposio et al. (9), which were instead placed into the genomes of HCMV strains Ad169 and FIX. The mutations in rκB− were repaired by allelic exchange of the kanamycin resistance gene with the gentamicin resistance gene to create the revertant wild-type (revWT) virus. The rCRE5MκB4M (rCRE−.κB−) contains the combination of mutations present in rCRE− and rκB−. rCRE−.κB− was derived from rκB−. All recombinant viruses were first screened for adventitious mutations by DNA sequencing through the intended regions of recombination and subjecting whole genomes to EcoRI restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Two recombinant clones from independent recombination procedures were subjected to analyses for confirming phenotype concordance.

PKC inhibitors were added to NT2 growth medium lacking knockout serum replacement medium at the indicated concentrations 30 min before and throughout phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) stimulation. Vehicle only was added to the unstimulated control cells. EDTA (1.5 mM) was added 30 min before and during stimulation (28). The half-maximal (50%) inhibitory concentration (IC50) of the specified inhibitor was determined by a dose-response curve. The percent inhibition was determined from quantitative measurements of MIE-positive (MIE+) NT2 cell density by using an immunofluorescence assay (IFA) method in conjunction with digital fluorescent microscopy and ImageJ analysis. The IC50 was estimated from a semilogarithmic graph of values of percent inhibition versus inhibitor concentrations (e.g., 0, 25, 50, 100, and 200 nM).

PMA stock (50 μM; Sigma) was prepared in ethanol. Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) (100 μM stock; Calbiochem/EMD Biosciences) was dissolved in PBS containing 1% human serum albumin. Bisindolylmaleimide (BIM-I) and BIM-II (10 mM stock), Ro-32-0432 (2 mM stock), GÖ6976 (1 mM stock), and GÖ6983 (2 mM stock) were purchased from Calbiochem/EMD Biosciences and prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Plasmids, transfection, and RNAi.

RNA interference (RNAi) experiments entailed the use of Suresilencing short hairpin RNA (shRNA) plasmids (SA BioSciences, Frederick, MD) containing the simian virus 40 (SV40) promoter-puromycin cassette and the U1 promoter driving the expression of shRNA against CREB (5′-TCATCTGCTCCCACCGTAACT-3′), PKC-delta (r, 5′-CACCCAGAGACTACAGTAACT-3′; g, 5′-CCCAGAGACTACAGTAACTTT-3′), PKC-epsilon (g, 5′-AGGAAGAGTGTATGTGATCAT-3′), RelA (y, 5′-GCTCAAGATCTGCCGAGTGAA-3′; b, GACCTTCAAGAGCATCATGAA-3′), RelB (g, 5′-GCGGATTTGCCGAATTAACAA-3′; b, 5′-GGAGATCATCGACGAGTACAT-3′; y, AGCCCGTCTATGACAAGAAAT), p105/50 (b, 5′-GAACCATGGACACTGAATCTA-3′; y, 5′-CTGCAGCTGTATAAGTTACTA-3′), or TORC2 (r, 5′-CCAGGTTTCTCTAAGGAGATT-3′; b, 5′-TGAAGTCCCTGGAATTAACAT-3′; y, 5′-GCAGCGAGATCCTCGAAGAAT-3′; g, 5′-CAGCAGCTGCCCAAACAGTTT-3′) (“r,” “g,” “b,” and “y” are shRNAs). Negative-control (NC) shRNA consisted of the sequence 5′-GGAATCTCATTCGATGCATAC-3′.

Plasmid pCMV-TORC2 contains human TORC2 that is C-terminally tagged with Myc and Flag (59). The pCMV6Entry vector (Origene Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD) serves as this plasmid's backbone and without the TORC2 insert is designated pCMV. Plasmid clones expressing Flag-rat PRKCD-K376M and Flag-rat PRKCD were graciously provided by Ushio Kikkawa (27).

NT2 cells in 30-mm2 dishes or 12-well plates were transfected by using endotoxin-free plasmid DNA and the Lipofectamine LTX and Plus reagent combination (Invitrogen) according to an experimental method reported previously by Yuan et al. (59). Transfection efficiency ranged from 60 to 80%. For RNAi studies, HCMV infection was performed at 48 h after transfection with the plasmids expressing shRNA (59). PMA stimulation was carried out from 2 to 26 h p.i. Thus, RNAi-mediated knockdown was carried out for 72 h, and PMA stimulation was carried out for 24 h. Knockout serum replacement medium was omitted from the growth medium throughout the stimulation. Plasmids pCMV-TORC2 and pCMV were transfected for 48 h before subjecting NT2 cells to infection followed by VIP or PMA stimulation.

Nucleic acid analyses.

HCMV DNA from each sample was quantified in quadruplicate by the TaqMan real-time PCR method using ABI Prism 7700 and 7000 sequence detection systems (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). A primer set and probe targeting the MIE enhancer were used (25). Nuclei and DNA were prepared by using methods described previously (38). Primers and probes for the quantification of cellular glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) DNA were purchased from Applied Biosystems. The standard curve method was applied to determine the relative concentration of target DNA in relationship to the threshold cycle (CT) value.

Whole-cell RNA was isolated according to a method described previously by Chomczynski and Sacchi (12). cDNA was synthesized by using Superscript II RNase H− reverse transcriptase (RT) (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) and random hexamers. Target cDNA in each sample was quantified in five to six replicates by real-time PCR using the primers, probe, and amplification conditions reported previously (37). The primers target MIE exons 1 and 2 to produce an MIE amplicon spanning intron A. The cDNAs derived from ribosomal 18S were amplified and detected by using reagents purchased from Applied Biosystems. The standard curve method was applied to determine the relative concentration of target cDNA in relationship to the CT value.

Protein analyses.

Western blots of whole-cell extracts were performed by using methods reported previously (25, 38). Cell extracts used for the analyses of phosphorylation levels of CREB, PKC-delta, and TORC2 were made in the presence of Calbiochem phosphatase inhibitor cocktail sets I and II (EMD Biosciences), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE on 7.5 or 10% Tris-glycine gels and transferred onto Protran BA85 nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell BioScience, Keene, NH). Blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies in 1× PBS containing 5% dried milk, incubated with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or mouse IgG F(ab′) fragment (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) at room temperature for 2 h or overnight at 4°C (1:50,000 to 1:250,000 dilution of an 0.8-mg/ml stock) in PBS containing 5% dried milk, treated with SuperSignal West Femto maximum-sensitivity substrate (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, IL), and exposed to autoradiography film. Primary antibodies were used at 1:500 to 1:2,000 dilutions and include rabbit polyclonal anti-CREB (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-CREB (Upstate Biotechnology), monoclonal murine anti-ATF-1 (25C10G) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), polyclonal rabbit anti-PKC-delta (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), polyclonal rabbit anti-phospho-Thr505 PKC-delta (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), polyclonal rabbit anti-PKC-epsilon (BD Bioscience Pharmingen, San Jose, CA), murine monoclonal anti-beta tubulin (E7) (University of Iowa Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA), rabbit polyclonal anti-Oct4 (Chemicon-Millipore Corporation), rabbit monoclonal anti-RelA (Epitomics, Inc., Burlingame, CA), rabbit monoclonal anti-p105/50 (Epitomics, Inc.), rabbit monoclonal anti-RelB (Epitomics, Inc.), rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-Ser171 TORC2 (Cell Signaling), rabbit polyclonal anti-CRTC2 (TORC2; ProteinTech Group, Inc., Chicago, IL), and murine monoclonal anti-Flag (OriGene Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD). HCMV IE1 p72 and IE2 p86 were detected by using monoclonal murine antibody MAB810 (Chemicon International, Charlottesville, VA), which reacts to an epitope in both proteins. The rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-CREB antibody against phospho-Ser133 in CREB residues 126 to 136 cross-reacts with ATF-1 phospho-Ser63 (Upstate Biotechnology) (25). Densitometry analysis of the band intensity on exposed film was performed by using the NIH ImageJ 1.34s program.

For IFA of the HCMV MIE protein, duplicate samples of cells were fixed in ice-cold methanol for 5 min, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, and blocked with 10% goat serum in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. Murine monoclonal antibody against the HCMV IE1 p72 and IE2 p86 proteins (MAB810) (Chemicon International) (1:1,000 to 1:2,000 dilution) in 10% goat serum in PBS was applied for 1 h at 37°C or overnight at 4°C. Secondary goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 555 (Molecular Probes Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) was applied at 1:1,000 to 1:5,000 dilutions for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were counterstained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (1 mg/ml). Images were captured by an inverted Olympus IX 51 fluorescent microscope equipped with an X-Cite 120 fluorescence illumination system. The ratio of MIE cells (Alexa Fluor 555 positive) to total cells (DAPI positive), with calculated means and standard deviations (SD), was determined with NIH ImageJ 1.34s software applied to three to eight representative captured images, each comprising the entire field of original magnification of ×20. In the case of manual counting, paired images of MIE- and DAPI-positive NT2 cells were divided into 50 zones of equal size. Ten zones were randomly selected for manual counting of MIE- and DAPI-positive cells. Means and standard deviations were calculated for the percentage of MIE-positive cells among DAPI-positive cells.

RESULTS

PMA activates a novel PKC isoform to immediately increase the levels of expression of HCMV MIE RNA and protein and the MIE+ NT2 cell population density without changing levels of HCMV genome penetration or the Oct4 marker of stem cell pluripotency.

A previous report of the PKA-CREB-TORC2 signaling cascade's involvement in VIP-induced HCMV MIE gene expression referred to an ancillary immunofluorescence assay (IFA) result revealing that phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) also increases HCMV MIE protein expression levels in the NT2 cell model (59). To validate and extend this initial observation, we analyzed levels of both MIE RNA and protein at several time points during the first 24 h following PMA stimulation of quiescently infected NT2 cells.

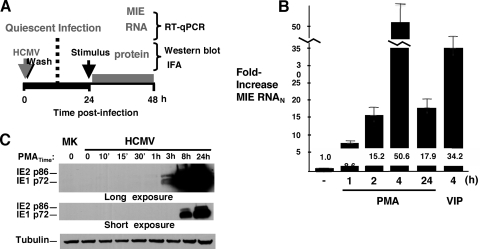

The NT2 cell model applied herein was previously characterized (25, 36, 59). The experimental approach depicted in Fig. 1 A entails the inoculation of cultured NT2 cells with HCMV particles partially purified by zonal centrifugation (MOI of 3 to 5) to establish a quiescent infection for 24 h before the commencement of PMA stimulation, followed by serial measurements of MIE RNA and protein production by RT-quantitative PCR (qPCR) and Western blotting or IFA methods, respectively (25, 36). As shown in Fig. 1B, spliced MIE RNA levels rose by 8.6-fold as early as 1 h after the addition of PMA to growth medium. The increase in levels of MIE RNA was greatest at 4 h poststimulation (50.6-fold) and waned at 24 h (17.9-fold), possibly reflecting negative autoregulation by the viral MIE gene product, IE2 p86. The HCMV MIE proteins IE1 p72 and IE2 p86 become detectable by Western blotting at 3 h poststimulation (Fig. 1C). This result is in accordance with that of MIE RNA expression. Notably, both the IE1 p72 and IE2 p86 proteins further increase in abundance at 8 and 24 h poststimulation.

FIG. 1.

PMA stimulation immediately increases the expression levels of HCMV MIE RNA and protein. (A) Schematic diagram of the experimental design for PMA-induced HCMV MIE gene activation from quiescent infection in NT2 cells. Infection is carried out with HCMV strain Towne at an MOI of 3 to 5 PFU per cell. PMA is added at final 20 nM concentrations to NT2 growth medium minus knockout serum replacement medium. Characteristics of the NT2 cell model were specified previously (25, 36). (B and C) Time course for analyses of PMA-induced expression of HCMV spliced MIE RNA (B) and proteins (IE1 p72 and IE2 p86) (C). The level of HCMV spliced MIE RNA was measured by RT coupled with real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) and normalized to the cell 18S RNA (MIE RNAN) level, also measured by RT-qPCR. Means and SD of data from triplicate experimental samples depict fold changes in HCMV MIE RNAN levels. The IE1 p72 and IE2 p86 proteins were detected by Western blotting using a primary antibody against the amino-terminal portion shared by both proteins. β-Tubulin served as an internal control. Independent experimental samples in duplicate were pooled for Western blot analysis. See Materials and Methods for details. MK, mock infection.

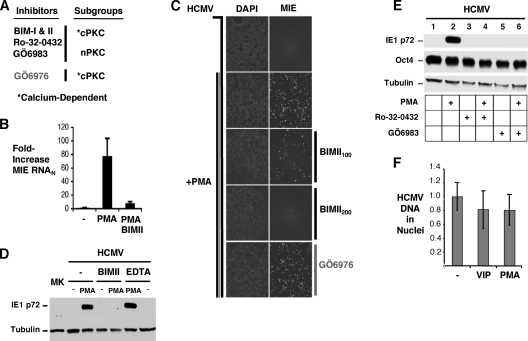

To back the conjecture that PKC is probably involved in PMA-induced MIE gene expression, we first determined whether the pharmacological inhibition of one or more of the different PKC subgroups attenuates the PMA effect. NT2 cells are known to express the cPKC members alpha, beta1, beta2, and gamma and the nPKC-delta isoform (1, 23, 29, 44, 45, 47). The cPKC and nPKC subgroups differ in their degrees of susceptibility to specific PKC inhibitors, and members of the cPKC subgroup have a characteristic dependency on calcium for activity. The PKC inhibitors selected for study and their preferential targets are depicted in Fig. 2A. Each of the inhibitors was added 30 min before and throughout PMA stimulation after initially undergoing testing in NT2 cells to assess cellular toxicity in the concentration range that reportedly provides an inhibition of activity of the targeted PKC isoform. Rotterlin is an example of an inhibitor that was not amenable to further study because of causing cellular toxicity in the concentration range needed for PKC-delta inhibition (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

PMA-induced increases in MIE gene expression and MIE+ NT2 cell population density require a novel PKC isoform and are not accompanied by changes in levels of HCMV genomes in nuclei or the Oct4 marker of stem cell pluripotency. (A) Schematic diagram of PKC inhibitors and their targets. Bisindolylmaleimide I (BIM-I), BIM-II, Ro-32-0432, and GÖ6983 inhibit activities of members of the conventional and novel PKC subgroups (cPKC and nPKC, respectively), whereas GÖ6976 inhibits members of the cPKC subgroup. The conventional PKC subgroup is dependent on calcium for activity. The indicated PKC inhibitors or EDTA was added 30 min before and throughout PMA (20 nM) stimulation. (B) MIE mRNA was quantified by RT-qPCR at 4 h poststimulation, as described in the legend of Fig. 1 (BIM-II, 100 nM). (C to E) MIE protein (IE1 p72 and IE2 p86) was detected by IFA (C) and Western blotting (D and E) at 24 h poststimulation (BIM-II, 100 nM [C and D] and 200 nM [D]; GÖ6976, 500 nM [C]; Ro-320432, 100 nM [E]; GÖ6983, 100 nM [E]; EDTA, 1.5 mM [D]). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Original magnification, ×10 (D). β-Tubulin served as an internal control for all Western blots; the Western blot in E was also probed for Oct4. (F) HCMV DNA in cell nuclei at 48 h p.i. was also quantified by real-time PCR and normalized to cellular 18S DNA (HCMV DNAN) levels. Means and SD of triplicate experimental samples depict fold changes in HCMV DNAN levels. VIP (100 nM) and PMA (20 nM) were added for 24 h.

Representative results are provided in Fig. 2B to D. The PMA-induced expression of MIE RNA (Fig. 2B) and protein (Fig. 2C and D) is blocked by bisindolylmaleimide II (BIM-II) at a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 25 to 75 nM (data not shown). The related BIM-I inhibitor produced similar results (IC50 of 25 to 75 nM) (data not shown). Both BIM-I and -II inhibit conventional PKC and novel PKC-delta and -epsilon. In contrast, the application of 500 nM GÖ6976, a selective inhibitor of conventional PKC, is not effective at blocking the PMA effect (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, the chelation of calcium by EDTA also fails to inhibit PMA-induced MIE gene expression (Fig. 2D). As anticipated, the pharmacological inhibition of PKA also did not appreciably decrease the PMA effect (data not shown). These findings suggest that a novel PKC isoform conveys the PMA response.

In broadly exploring the possible ways in which PMA-induced PKC activation enables MIE gene expression, we examined whether PMA alters the cellular state of pluripotency or the HCMV genome's ability to reach the cell nucleus in a time frame relevant to MIE gene expression. Figure 2E reveals that PMA stimulation does not significantly lower levels of cellular Oct4, which serves as a master regulator of the pluripotent stem cell gene expression program (34). This result is consistent with an earlier report stating that phorbol ester does not stimulate NT2 cellular differentiation (29). Ro-32-0432 and GÖ6983, inhibitors of both cPKC and nPKC, also do not appreciably change the cellular Oct4 amount yet effectively block PMA-induced MIE protein expression. Importantly, PMA stimulation does not change the amount of HCMV genomes cofractionating with NT2 cell nuclei, implying that the relative penetration efficiency of HCMV genomes into NT2 cell nuclei is unchanged by PKC activation. Collectively, the data strongly suggest that PMA immediately increases MIE gene expression levels from quiescent HCMV genomes through a mechanism that involves nPKC activation and is not accompanied by a change in the undifferentiated pluripotent NT2 cell state.

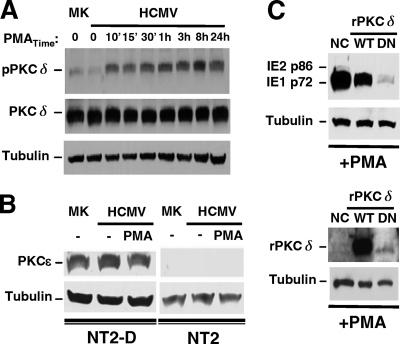

PMA-activated MIE gene expression requires PKC-delta and coincides with PKC-delta Thr505 phosphorylation.

Our investigation was narrowed to addressing the individual roles of specific nPKC isoforms, PKC-delta and PKC-epsilon, in PMA-activated MIE gene expression. The data shown in Fig. 3A reveal that the full-sized PKC-delta protein of 78 kDa is abundantly produced in this NT2 cell model. The amount of PKC-delta does not change with HCMV infection or PMA stimulation. The phosphorylation of the PKC activation domain may render the enzyme catalytically competent (26). Thr505 in the PKC-delta activation domain is a target for phosphorylation (26). The basal amount of PKC-delta Thr505 phosphorylation does not differ at 24 h p.i. from that of mock-infected NT2 cells. In contrast, PMA stimulation quickly increases PKC-delta Thr505 phosphorylation at levels that are sustained throughout the 24-h period of PMA stimulation: 8.0- and 6.1-fold increases at 8 and 24 h poststimulation compared to the unstimulated infected cell group. Unlike PKC-delta, the PKC-epsilon isoform is not detectable in whole NT2 cell extracts by Western blotting but is clearly evident in the differentiated NT2 (NT2-D) cell counterparts (Fig. 3B). PKC-epsilon RNA was detected in only very small amounts by RT-qPCR of NT2 cells (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

PKC-delta is abundant (unlike PKC-epsilon), and its phosphorylation at Thr505 coincides with PMA-induced MIE gene activation, which is inhibited by the ectopic expression of a dominant-negative PKC-delta. (A and B) The experimental design described in the legend of Fig. 1A was applied to analyze mock-infected (MK) and infected NT2 or differentiated NT2 (NT2-D) cells after PMA stimulation. Duplicate samples were pooled for Western blot analyses, and β-tubulin served as the internal control. (A) Amounts of total PKC-delta (PKCδ) and PKC-delta containing phospho-Thr505 (pPKCδ) were assessed at the indicated times of PMA stimulation in MK and infected NT2 cells. The ratio of pPKCδ to PKCδ was calculated for determinations of fold changes in levels of PKC-delta phosphorylation. (B) The amount of PKC-epsilon (PKCɛ) was assessed in MK and infected NT2 and NT2-D cells at 24 h poststimulation with and without PMA. (C) NT2 cells were transfected with equivalent amounts of a negative-control (NC) expression plasmid or a plasmid expressing Flag-tagged rat wild-type (WT) PKC-delta (rPKCδ) or dominant-negative (DN) rPKCδ at 24 h prior to infection and then treated by using the approach depicted in Fig. 1A. The amount of the MIE protein was assessed at 24 h poststimulation. The NC plasmid contains an SV40 promoter driving puromycin. Tagged WT and DN rPKCδ were detected with anti-Flag antibody. DN rPKCδ resulted in 93% and 90% decreases in PMA-induced IE1 p72 expression relative to NC and WT rPKCδ, respectively.

To explore the specific role of PKC-delta in PMA-activated MIE gene expression, a kinase-negative PKC-delta isoform was ectopically expressed from a plasmid transfected into NT2 cells prior to infection. This kinase-negative PKC-delta clone is a derivative of rat PKC-delta, contains a mutation producing a single-amino-acid Lys376Met change, and functions in a dominant-negative (DN) fashion in primate cells to inhibit stimulus-induced PKC-delta activity (27). As shown in Fig. 3C, the plasmid expressing DN PKC-delta greatly attenuates PMA-induced IE1 p72 protein expression (90 to 93% reduction) compared to a negative-control (NC) expression plasmid or a plasmid expressing parental wild-type (WT) rat PKC-delta despite a weak expression of DN PKC-delta. This result suggests that the PMA response requires PKC-delta.

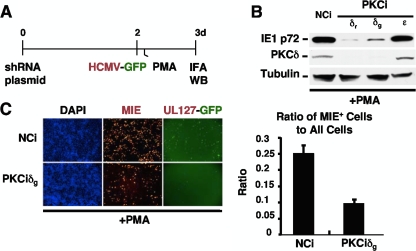

We sought to validate this conclusion by an alternative approach. The depletion of endogenous PKC-delta was carried out by using the modified experimental design depicted in Fig. 4A. NT2 cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing short hairpin RNA (shRNA) that specifically targets PKC-delta for depletion by RNA interference (PKCδi) or plasmid expressing negative-control shRNA (NCi). Infection was performed at day 2 posttransfection with HCMV Towne expressing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene under the control of the viral native UL127 early/late kinetic-class promoter (33). HCMV MIE protein expression was evaluated at 22 h after PMA stimulation. As revealed by Western blotting (Fig. 4B), the depletion of PKC-delta is achieved by either PKCiδr or PKCiδg, which target different nucleotide sequences within PKC-delta. The knockdown of PKC-delta (PKCδ) lowers PMA-induced IE1 p72 protein expression by 11- to 32-fold compared to NCi-treated cells. The IFA data reveal that the PKC-delta knockdown also attenuates the PMA-induced increase in the MIE+ NT2 cell population density (Fig. 4C). The parallel finding of a reduction in the PMA-induced NT2 cell subpopulation expressing HCMV UL127-GFP is also striking and, presumably, a consequence of the decrease in levels of MIE gene expression. Thus, PMA-activated MIE gene expression is dependent on PKC-delta and in step with PKC-delta Thr505 phosphorylation that is sustained throughout the period of PMA stimulation.

FIG. 4.

PMA-activated MIE gene expression is attenuated by RNAi-mediated depletion of PKC-delta. (A) NT2 cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing shRNA against PKC-delta (PKCiδr or PKCiδg), PKC-epsilon (PKCiɛ), or the negative control (NCi) for 72 h. HCMV infection was carried out with an HCMV recombinant expressing GFP under the control of the viral native UL127 early/late kinetic-class promoter (33) at 48 h after PKC knockdown. PKCiδr and PKCiδg differ only in the nucleotide sequences that they target within PKC-delta. PKCiɛ was determined beforehand to decrease PKC-epsilon RNA expression levels (data not shown). (B and C) The MIE protein (IE1 p72) level was detected by Western blotting (WB) (B) and IFA (C) at 22 h of PMA stimulation. (B) Data from independent samples in duplicate were pooled for Western blot analysis. PMA-induced IE1 p72 levels decreased by 32- and 11-fold by PKCiδr and PKCiδg, respectively, compared to NCi and normalized to β-tubulin. (C) The bar graph depicts the ratio of MIE+ cells to all cells by treatment condition; means and SD were determined from five random fields by using NIH ImageJ 1.34s software. GFP expression was imaged by live-cell microscopy prior to sacrificing cells for IFA. Original magnification, ×10.

PMA-activated HCMV MIE gene expression is partially dependent on viral MIE enhancer CRE repeats and cellular CREB but is not dependent on cellular TORC2.

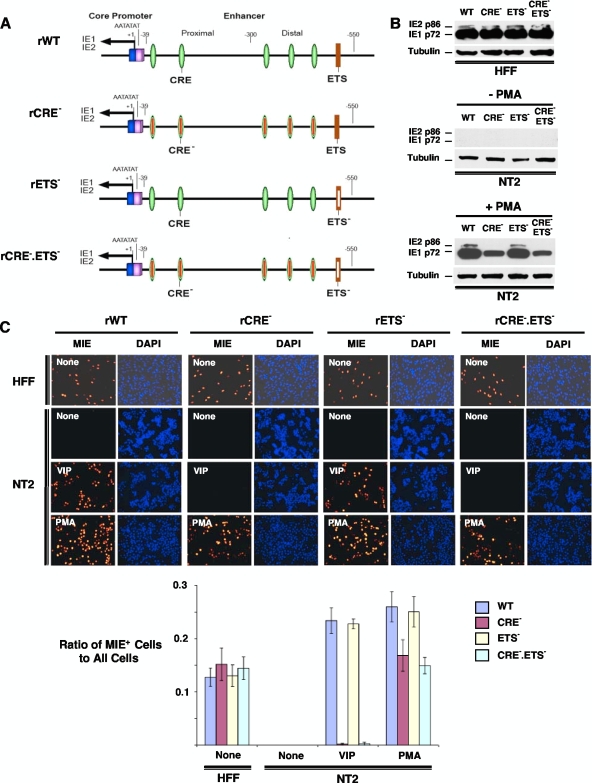

In transient assays, PKC has been implicated in mediating phorbol ester-activated CRE-dependent transcription from MIE enhancer/promoter segments transfected into myeloid and lymphoid cell types (20, 56). Transient assays of monocytic cell lines have also identified the ETS binding site as conferring phorbol ester-induced activity to MIE enhancer/promoter segments derived from human and nonhuman primate CMVs (11). To directly determine the functional roles of HCMV's MIE enhancer CRE and ETS elements in the PMA response, we used BACmid-based technology to construct a set of recombinant HCMVs bearing critical base substitution mutations in CRE only, ETS only, or both CRE and ETS in the MIE enhancer (Fig. 5A). Each of five CRE copies in rCRE− and rCRE−.ETS− contains the same two-base substitution mutations that were reported previously by Keller et al. (24) to eliminate MIE CRE function in an otherwise wild-type HCMV. The ETS element in rETS− and rCRE−.ETS contains the same three-base substitution mutations that were determined previously by Chan et al. (11) to eliminate the phorbol ester response of the MIE enhancer/promoter in transient assays.

FIG. 5.

PMA-activated MIE gene expression is partially dependent on the MIE enhancer CRE repeats, whereas the ETS binding site is noncontributory. (A) Schematic diagram of HCMV rCRE5M (rCRE−), rETS1M (rETS−), and rCRE5M ETS1M (rCRE−.ETS−) compared to wild-type parent HCMV (rWT). These viruses were constructed as HCMV Towne BACmids, as detailed in Materials and Methods. Each of five copies of CRE in rCRE− and rCRE−.ETS− is disrupted by the same two-base substitution mutations that were reported previously by Keller et al. (24) to eliminate MIE CRE activity in the context of the HCMV genome. The ETS binding sequence at base position −538 in the HCMV MIE enhancer/promoter was changed from GTTCCGC to GTgaaGC in both rETS− and rCRE−.ETS−, given the findings described previously Chan et al. (11) that indicate that these three-base substitution mutations in the comparable element of simian CMV eliminate phorbol ester-induced MIE enhancer/promoter responsiveness in transient assays with monocytic cells. (B and C) Human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) and NT2 cells were inoculated in parallel with equivalent titers of the viruses (MOIs of 0.3 for HFF and 3 for NT2 cells). MIE proteins (IE1 p72 and IE2 p86) were analyzed by Western blotting (B) and IFA (C) at 24 h poststimulation with VIP (100 nM), PMA (20 nM), or nothing. Duplicate experimental samples were pooled for Western blot analyses. The MIE protein was analyzed at 24 h p.i. for HFF and at 48 h p.i. for NT2 cells. Relative to the rWT IE1 p72 level, the percent decreases in the IE1 p72 levels normalized to tubulin are 55%, 14%, and 60% for rCRE−, rETS−, and rCRE−.ETS−, respectively. Original magnification for IFA, ×20. The bar graph in C depicts the ratio of MIE+ cells to all cells; means and SD were determined from five random fields by using NIH ImageJ 1.34s software.

The HCMV Towne constructs were first evaluated in parallel in productively infected human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF). These analyses reveal that mutations targeting CRE only and ETS only do not dysregulate viral MIE gene expression from rCRE− and rETS−, respectively (Fig. 5B and C and data not shown). This result is consonant with results of prior studies of differently designed HCMV constructs having mutations in CRE only (24) or the adjoining ETS and serum response element (37) and lacking an insertion of a BACmid or other foreign DNA. Notably, the unique combination of mutations in both CRE and ETS in rCRE−.ETS− also does not result in a dysregulation of MIE gene expression or viral replication in HFF (Fig. 5B and C and data not shown). In PMA-stimulated quiescently infected NT2 cells, the mutations in CRE decrease the level of PMA-induced production of IE1 p72 by both rCRE− and rCRE−.ETS− compared to that of the rWT (2.6- to 3.8-fold decreases, respectively) (Fig. 5B). The IFA data shown in Fig. 5C also reveal that CRE mutations partially attenuate the PMA-induced increase in the MIE+ NT2 population density for rCRE− and rCRE−.ETS− by 55% and 60%, respectively. The CRE mutations nearly abolish VIP's ability to activate these genes (Fig. 5C and data not shown). The difference between PMA and VIP results implies that PMA is also acting through a CRE-independent mechanism. The ETS site characterized previously by Chan et al. (11) contributes negligibly to the PMA response, because a disruption of ETS has a very minimal effect on HCMV MIE protein production in the PMA-stimulated NT2 cell model (Fig. 5B and C).

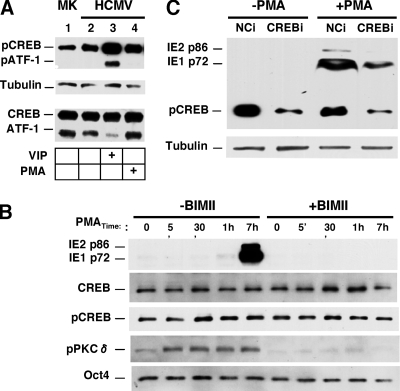

The five CREs in the MIE enhancer are potential binding sites for CREB family members. The phosphorylation of CREB at Ser133 (pCREB) and the phosphorylation of ATF-1 at Ser63 (pATF-1) render these transcription factors competent for transcriptional activation. Notably, pCREB is abundant prior to the stimulation of quiescently infected NT2 cells, and its level rises only modestly in response to FSK or VIP stimulation (59). Here, we show that PMA only marginally increases levels of CREB Ser133 phosphorylation in quiescently infected NT2 cells when sequentially examined at 5, 30, 60, and 420 min poststimulation (Fig. 6A and B). Levels of CREB (total), tubulin, and the Oct4 pluripotent stem cell marker remained stable. PMA differs from VIP in not appreciably increasing ATF-1 Ser63 phosphorylation (Fig. 6A). While the pharmacological inhibition of nPKC with BIM-II effectively blocks the PMA-induced increases in levels of PKC-delta Thr505 phosphorylation and MIE expression, it does not decrease the high baseline value of CREB Ser133 phosphorylation (Fig. 6B). Hence, pCREB is abundant and likely available to carry out PMA-activated CRE-dependent MIE gene expression. To evaluate the functional role of CREB, CREB was selectively depleted by RNAi (CREBi) using the experimental approach depicted in Fig. 4A and CREB-specific shRNA that was validated previously for these cells (59). As shown in Fig. 6C, CREBi results in a 75% reduction in the pCREB level compared to infected cells receiving negative-control shRNA (NCi). This leads to a 67.1% reduction in the amount of IE1 p72 expression in response to PMA stimulation.

FIG. 6.

PMA-activated MIE gene expression is partially dependent on cellular CREB, with marginal increases in CREB Ser133 phosphorylation above its high-basal level. (A) Western blot analysis comparing VIP- and PMA-induced CREB Ser133 and ATF-1 Ser63 phosphorylation levels in conjunction with total amounts of CREB and ATF-1. Infections were performed according to the approach described in the legend of Fig. 1A. Whole-cell extracts were analyzed at 30 min of stimulation with VIP (100 nM) or PMA (20 nM). Independent duplicate samples were pooled for analysis. The same phospho-specific antibody detects both phospho-Ser133 in CREB (pCREB) and phospho-Ser63 in ATF-1 (pATF-1). β-Tubulin served as an internal control. (B) Western blot analyses of MIE proteins (IE1 p72 and IE2 p86), CREB, pCREB, pPKCδ, and Oct4 at the indicated times after PMA stimulation in the presence or absence of BIM-II (100 nM). Infection and PMA stimulation were performed according to the approach described in the legend of Fig. 1A. Independent duplicate samples were pooled for analysis. (C) NT2 cells were transfected with plasmid expressing shRNA against CREB (CREBi) or a negative control (NCi) for 72 h. HCMV infection and PMA stimulation were performed according to the approach described in the legend of Fig. 4A. Expression levels of MIE proteins (IE1 p72 and IE2 p86) were analyzed by Western blotting at 22 h poststimulation with or without PMA. CREBi produced a 75% reduction in the pCREB level and a 67.1% reduction in the IE1 p72 level compared to NCi and normalized to β-tubulin.

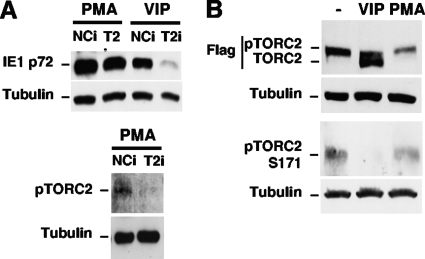

Interestingly, the knockdown of the TORC2 level by TORC2i (T2i) does not attenuate PMA-activated MIE protein expression, in contrast to the decrease in VIP-induced MIE protein expression levels that it produces (Fig. 7A). PMA also differs from VIP in not causing a dephosphorylation of TORC2 that is reflected in TORC2 electrophoretic mobility and Ser171 phosphorylation (59) (Fig. 7B). These data imply that TORC2 remains in its inactive phosphorylated form in PMA-stimulated NT2 cells. Taken together, the results indicate that PMA reverses MIE gene silence through a signaling cascade that partially involves viral MIE CRE and cellular pCREB but does not involve the CREB coactivator TORC2.

FIG. 7.

PMA-activated MIE gene expression is not mediated by cellular TORC2, unlike the results of VIP stimulation. (A) NT2 cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing shRNA against TORC2 (TORC2i) or a negative control (NCi) for 72 h. These cells were then infected for 24 h and stimulated with VIP or PMA using the approach described in the legend of Fig. 4A. Expression levels of MIE proteins (IE1 p72 and IE2 p86) were analyzed by Western blotting at 22 h poststimulation. The knockdown of phosphorylated TORC2 (pTORC2 Ser171) in the PMA-treated group was detected with phospho-Ser171 antibody. β-Tubulin served as an internal control. (B) NT2 cells were transfected for 48 h with a plasmid expressing TORC2 tagged with Flag. Whole-cell extracts were subjected to Western blotting at 15 min of VIP (100 nM) or PMA (20 nM) stimulation or no stimulation. Tagged pTORC2 and TORC2 were detected with anti-Flag antibody. Flag-tagged TORC2 Ser171 phosphorylation (pTORC2 Ser171) was detected with phospho-Ser171 antibody. Each experiment performed in duplicate, and the two samples were pooled for Western blot analyses prior to fractionation on 10% (A) or 7.5% (B) polyacrylamide gels.

PMA-activated HCMV MIE gene expression is partially dependent on viral MIE enhancer κB repeats and cellular NF-κB, whereas the κB is not involved in the VIP response.

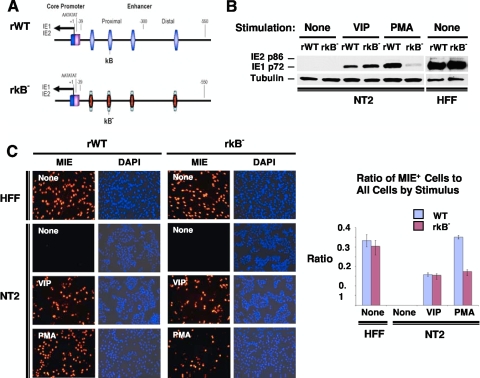

Having revealed that the HCMV MIE CRE only partially confers PMA's effect on MIE protein production, we investigated the possibility that PMA acts additionally through another type of MIE cis-acting element. The failure of inhibitors of the AP-1 signaling pathway to decrease PMA-induced MIE gene expression in quiescently infected NT2 cells (data not shown) focused our attention on the cellular NF-κB signaling pathway. Pharmacological inhibitors of the NF-κB signaling pathway yielded ambiguous results partly because of confounding cellular toxicity (data not shown). We therefore constructed a recombinant HCMV in which each of four NF-κB binding sites (κB) in the HCMV MIE enhancer was mutated with the same base substitution changes that were validated previously by Caposio et al. (9) in the context of another HCMV BACmid construct (Fig. 8A). The mutated κB elements in the newly constructed recombinant rκB− virus were then repaired to create the revertant wild-type (revWT) virus.

FIG. 8.

PMA-activated MIE gene expression is partially dependent on the HCMV MIE enhancer κB elements. (A) Schematic diagram of HCMV κB4 M (rκB−) compared to wild-type parent HCMV (rWT). rκB4 M has base substitution mutations in all four copies of κB elements in the MIE enhancer (9). The κB elements are located at base positions −94, −157, −262, and −413 relative to the +1 transcription start site. Both rWT and rκB4 M HCMV Towne BACmids are further described in Materials and Methods. (B and C) NT2 cells and HFF were inoculated with equivalent titers of rWT and rκB (MOIs of 3 for NT2 cells and 0.3 for HFF). MIE proteins (IE1 p72 and IE2 p86) were analyzed by Western blotting (B) and IFA (C) at 24 h after stimulation with VIP (100 nM), PMA (20 nM), or nothing. Duplicate experimental samples were pooled for Western blot analysis. The MIE protein was analyzed at 24 h p.i. for HFF and at 48 h p.i. for NT2 cells. Original magnification for IFA, ×20. The bar graph depicts the ratio of MIE+ cells to all cells; means and SD were determined from five random fields using NIH ImageJ 1.34s software.

We first determined that the mutated κB repeats in rκB− do not result in a dysregulation of MIE gene expression in serum-fed HFF at 24 h p.i. (Fig. 8B and C and data not shown), an outcome predicted based on previously reported results of other HCMV constructs containing κB mutations (4, 9, 18). However, a very different outcome transpired in PMA-stimulated quiescently infected NT2 cells. In this setting of infection, the findings show that κB mutations decrease PMA-induced IE1 p72 production by 87.8% (Fig. 8B) and the MIE+ NT2 cell population density by 49.5% (Fig. 8C) compared to those of the rWT. The revWT does not differ from the rWT in PMA-induced MIE protein expression (data not shown). The κB mutations do not change VIP's ability to increase MIE gene expression levels (Fig. 8B and C), supporting the idea that VIP and PMA operate through distinctively different signaling networks.

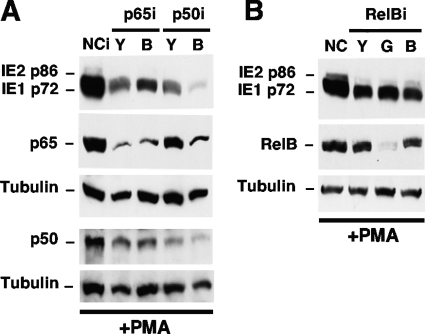

The functional contribution of the NF-κB activation pathway in the PMA response was assessed by the individual depletion of cellular p65 (RelA), p50/p105 (NF-κB1), and RelB using the RNAi-based experimental approach depicted in Fig. 4A. The findings in quiescently infected NT2 cells reveal that the RNAi-mediated depletion of p65 by 78 to 80% results in a 47 to 56% decrease in the PMA-induced production of IE1 p72 (Fig. 9A). Similarly, the RNAi-mediated knockdown of p50 (63 to 77% reduction) also decreases MIE protein production (77 to 95% reduction) (Fig. 9A). The greatest level of knockdown of PMA-induced IE1 p72 expression was observed for the p50iB group, where the 77% decrease in the p50 level by this RNAi also lowered the p65 level by 61%, possibly through a mechanism that involves cross talk or feedback through other transcriptional pathways (46). The effect of knocking down RelB, a distinguishing component of the noncanonical NF-κB activation pathway (46), was evaluated for three different RelB-specific shRNA molecules (Y, G, and B) that target different sites within RelBi RNA. Only RelBiG resulted in a substantial reduction in the level of the RelB protein (Fig. 9B). However, RelBiG does not decrease amounts of IE1 p72 and IE2 p86 any further than the small decrease produced by RelBiY and RelBiB compared to negative-control RNAi. This set of findings suggests that RelB does not have a major role in PMA-activated MIE gene expression in this system.

FIG. 9.

PMA-activated MIE gene expression is partially dependent on cellular NF-κB subunits p65 and p50. NT2 cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing shRNA against p65 (p65iY and p65iB), p50 (p50iY and p50iB), RelB (RelBiY, RelBiG, and RelBiB), or a negative control (NCi) for 72 h. These cells were then infected for 24 h and stimulated with PMA by using the approach described in the legend of Fig. 4A. The expression levels of MIE proteins (IE1 p72 and IE2 p86) were analyzed by Western blotting at 22 h poststimulation. Tubulin served as an internal control. Relative to NCi, p65iY and p65iB decreased levels of p65 by 80% and 78%, respectively, and decreased IE1 p72 levels by 56% and 47%, respectively. p50iY and p50iB decreased p50 levels by 63% and 77%, respectively, and decreased IE1 p72 levels by 77% and 95%, respectively; p50iB also decreased the p65 level by 61%, whereas p50iY decreased the p65 level by 31%. All results are normalized to tubulin levels.

Thus, the MIE enhancer's κB repeats also contribute to PMA-activated MIE gene expression but are not involved in the VIP response. The PMA-induced signal appears to be transduced mostly through the canonical or atypical NF-κB activation pathway given that MIE gene activation is greatly attenuated by the depletion of p65 or p50 but not RelB.

Mutations in both CRE and κB repeats eliminate PMA-activated MIE gene expression.

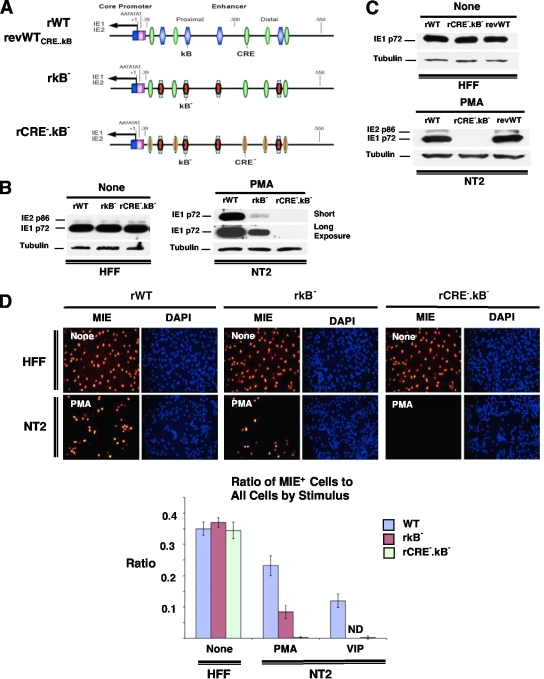

We next tested whether mutations introduced into both CRE and κB further decrease PMA's ability to activate MIE gene expression. The same site-directed mutations made in rCRE− and rκB− were combined to create rκB−.CRE− (Fig. 10A). The rWT, rκB−, and rκB−.CRE− produce equivalent levels of MIE protein expression in HFF (Fig. 10B to D). Strikingly, PMA-activated MIE protein expression in quiescently infected NT2 cells was almost completely abolished by mutations in both sets of CRE and κB repeats in the MIE enhancer, as measured by both Western blotting (Fig. 10B and C) and IFA (Fig. 10D). This level of decrease is greater than that for κB mutations alone. As expected, the CRE mutations in rκB−.CRE− also rendered this virus's MIE enhancer unresponsive to VIP stimulation (Fig. 10D). The repair of the CRE and κB mutations in rWTrκB−.CRE− restored PMA-activated MIE gene expression (Fig. 10C). These results provide additional evidence that both CRE and κB contribute to PMA-activated MIE gene expression in NT2 cells.

FIG. 10.

Combined mutations in the MIE enhancer CRE and κB repeats abolish PMA-activated MIE gene expression. (A) Schematic diagram of HCMV rCRE5MκB4M (rCRE−.κB−) compared to rκB4M (rκB−), wild-type parent HCMV (rWT), and the revertant WT HCMV derived from rCRE5MκB4M (revWTCRE..κB or revWT). rCRE−.κB− contains identical mutations in rCRE− and rκB−, as described in the legends of Fig. 5A and 8A, respectively. (B to D) NT2 cells and HFF were inoculated with equivalent titers of the specified viruses (MOIs of 3 for NT2 cells and 0.3 for HFF). MIE proteins (IE1 p72 and IE2 p86) were analyzed by Western blotting (B and C) and IFA (D) at 24 h after stimulation with VIP (100 nM), PMA (20 nM), or nothing. Duplicate experimental samples were pooled for Western blot analysis. The MIE protein was analyzed at 24 h p.i. for HFF and at 48 h p.i. for NT2 cells. The original magnification for IFA is ×20. The bar graph depicts the ratio of MIE+ cells to all cells; means and SD were determined from five random fields using NIH ImageJ 1.34s software.

DISCUSSION

Although HCMV latency has not yet been located to resting human pluripotent stem cells, this consideration remains possible in light of previous reports indicating that HCMV latency resides in primitive hematopoietic progenitors (17, 40, 58). The NT2 cell model permits a comprehensive characterization of signaling networks involved in the desilencing of the HCMV MIE gene locus during a quiescent HCMV infection, which can then provide insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying HCMV reactivation. Here, we report a series of original findings demonstrating that PMA stimulates a PKC-delta-dependent, TORC2-independent signaling cascade that relays through cellular CREB and NF-κB, as well as their cognate binding sites in the MIE enhancer, to immediately desilence the MIE gene locus. The PMA-activated signaling cascade is distinctively different from that elicited by VIP stimulation, although both signaling pathways involve CREB and ultimately result in HCMV MIE gene expression.

Our impression that PMA acts immediately on quiescent HCMV genomes to desilence MIE genes is based on the results of three experimental approaches. First, PMA acts within 1 h to increase MIE RNA production (Fig. 1B). This is quickly followed by increases in both the sum total of the MIE protein made by the entire NT2 cell population (Fig. 1C) and the proportion of cells expressing MIE proteins (Fig. 2C). Second, the PMA-elicited response is linked neither to cellular differentiation (Fig. 2E) nor to an appreciable change in the level of HCMV DNA penetration into NT2 cell nuclei (Fig. 2F). Third, the combined functioning of CRE and κB cis-acting elements in the MIE enhancer is required to convey the PMA response (Fig. 5, 8, and 10), a finding that also strengthens the view that the MIE enhancer in HCMV genomes is rendered inactive in NT2 cells unless stimulated.

A role for PKC-delta in HCMV infection has not been reported previously. Phorbol esters have been reported to enhance active HCMV infection in acutely infected human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) (55) and retinal pigmented epithelial (RPE) cells (13). Phorbol ester treatment of HUVEC prior to infection with the laboratory-adapted HCMV Ad169 strain, which is impaired in its ability to translocate to the HUVEC nucleus (54), increases the proportion of the cell population allowing active HCMV infection in a manner that is blocked by the PKC inhibitor staurosporin or RO-31-8220 (55). The treatment of RPE cells with phorbol ester before or shortly after infection enhances HCMV activity via a PKC-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, and this enhancement does not involve NF-κB activity (13). Notably, MCMV replication in acutely infected murine fibroblasts is blocked by PKC inhibitors, which manifests as a decrease in the level of MIE gene expression (28). In this study, MCMV MIE gene expression was only minimally inhibited by BIM-II at micromolar concentrations (28). This finding differs from that for HCMV-infected NT2 cells, in which BIM-II potently inhibited PMA-induced MIE gene activation at an IC50 of 25 to 75 nM (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Taken together, the results suggest that the response to phorbol ester is shaped by the specific conditions of the virus-cell interactions that govern the differential degrees of participation of the various PKC subtypes. Intriguingly, a recent report connected PKC-delta to the phorbol ester-induced reactivation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) (14), an evolutionarily distant relative of cytomegalovirus. This process takes place in primary effusion lymphoma cells and involves the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway (14).

Here, we provide several independent lines of evidence that link cellular PKC-delta to PMA-activated MIE gene expression in HCMV-infected NT2 cells. First, a battery of PKC inhibitors with different target specificities narrowed the field of candidates to an nPKC subtype (Fig. 2A to E). Second, PMA-activated MIE gene expression is greatly attenuated by the ectopic expression of a dominant-negative PKC-delta (Fig. 3C). Third, PKC-delta is abundant in these cells, and the level of phosphorylation of its activation domain at Thr505 correlates with the level of MIE gene expression (Fig. 3A and 6B). Fourth, the other nPKC subtypes are minimally or negligibly expressed (Fig. 3B) (1, 23, 29, 44, 45, 47), and the further lowering of the PKC-epsilon amount by RNAi does not appreciably attenuate the PMA response (Fig. 4B and data not shown). Lastly, the selective depletion of PKC-delta by RNAi greatly attenuates PMA-induced MIE gene activation as well as downstream viral UL127-GFP gene expression (Fig. 4).

Previous studies conducted with very different systems have revealed that phorbol ester can stimulate transcription from a select set of CREB-dependent genes, which is partly dictated by the nature of the cellular condition. In a subset of these specific circumstances, the activation of the PKC-delta isoform has been linked to the CREB-dependent transcription of cellular genes (6, 30, 62). CREB Ser133 is a substrate for multiple cellular kinases that include PKC, PKA, calcium-calmodulin-dependent kinases II and IV, MSK-1, PP90rsk, and MAP-KAP2 (35). The phosphorylation of CREB Ser133 (pCREB) by such kinases enables target gene activation by the recruitment of the transcriptional coactivators CBP and p300 (35, 41, 51). However, cellular genome-wide analysis has revealed that many pCREB-occupied genes in human cells are silent and that only a small subset of these silent genes are responsive to the FSK-induced elevation of the level of cAMP (61). This finding supports the view that other regulatory partners, such as CBP/p300, TAF4, ACT, and the family of TORC coactivators, further account for the signal discrimination through CREB (35, 50, 61). An analogous situation was posited previously for CREB target genes in quiescent HCMV genomes in NT2 cells (59). pCREB is abundant in these cells yet does not activate viral MIE genes (59). Furthermore, the activation of the cellular TORC2 coactivator is sufficient to activate MIE gene expression through a mechanism that involves the MIE enhancer CRE and cellular pCREB (59).

In NT2 cells, PMA stimulation only marginally increases the pCREB level above its high baseline value (Fig. 6A and B) and is poorly effective at increasing ATF-1 Ser63 phosphorylation (Fig. 6A), unlike the results for VIP stimulation (Fig. 6A) (59). We surmise that pCREB is needed for the PMA response, based on the observation that RNAi-mediated pCREB depletion partially blocks PMA-induced MIE gene expression (Fig. 6C). PMA differs importantly from VIP by acting instead through a TORC2-independent mechanism for the desilencing of MIE gene expression (Fig. 7). This dichotomy in signaling networks was recently shown in other cell types to result in the activation of two discrete sets of cellular CREB target genes when subjected to stimulation by FSK or phorbol ester (48). The composition of the HCMV MIE enhancer/promoter provides versatility in responding to either signaling cascade.

While the link between PMA stimulation and NF-κB-dependent transcription has been observed for a range of other human cell types, the precise mechanisms underlying this relationship are varied and often unclear. In one report, PKC-delta was determined to mediate the PMA-induced NF-κB-dependent transcription of reporter plasmids in the human pulmonary A549 cell line (19). The activation of PKC-delta by other stimuli (e.g., thrombin, bryostatin, and tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α]) is also sufficient to drive the NF-κB-dependent transcription of cellular genes (ICAM-1, interleukin-8 [IL-8], and RelA/p65) in human endothelial, epithelial, and osteosarcoma cells (5, 32, 43).

In HFF, smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and monocytes, HCMV infection rapidly results in NF-κB translocation to the cell nucleus and NF-κB binding to the κB site in DNA, regardless of the HCMV strain tested. Viral particle components themselves are sufficient to stimulate the signaling cascades that involve NF-κB activation (60). In contrast, HCMV Ad169 infection of retinal pigmented epithelial cells does not increase NF-κB DNA binding or entry into the cell nucleus (13). However, the treatment of these cells with the phorbol ester 12,0-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA) greatly increases nuclear NF-κB binding activity, but surprisingly, the enhanced NF-κB binding activity does not account for the TPA-induced activation of HCMV Ad169 MIE gene expression in these cells (13).

We show with quiescently infected NT2 cells that the cellular NF-κB subunits RelA/p65 and p105/50 contribute to PMA-induced MIE gene activation (Fig. 9). The finding that RelB's role is negligible to minimal suggests that the signal is transduced through the canonical or atypical NF-κB activation pathway. Interestingly, TNF-α does not desilence the HCMV MIE genes in this system despite activating RNA expression from a cellular gene subset (data not shown). Thus, PMA and TNF-α operate through different NF-κB activation pathways in NT2 cells. We have not discounted the possibility that the κB sites also interact with cis-acting sites other than CRE to achieve MIE enhancer activation during viral quiescence. Such a κB interaction with ETS and serum response factor binding sites in quiescently infected fibroblasts was recently revealed (8). Future studies are warranted to further characterize the NF-κB signaling pathway(s) involved in HCMV activation from the preexisting state of viral quiescence.

Overall, our results support a paradigm whereby PMA-induced PKC-delta-activated MIE gene expression is carried out by cellular pCREB and NF-κB that act through the CRE and κB cis-acting elements, respectively, in the MIE enhancer of resting HCMV genomes. TORC2 is not involved. The view that pCREB and NF-κB occupy their respective cis-acting elements in the MIE enhancer of activated HCMV genomes is plausible but requires formal testing. Comparative analyses of PMA and VIP reveal that these two stimuli operate through distinctly different signaling networks to overcome MIE gene silence. This conclusion aligns with the hypothesis that MIE enhancer/promoter silencing is optimally relieved through the concomitant actions of multiple regulatory mechanisms (25, 39). Our initial extended studies of this model show that combined stimulation with PMA and VIP produces synergistic levels of HCMV MIE gene expression (59a). The NT2 cell model reveals fundamental findings that will inform ex vivo HCMV latency models and human translational studies to both delineate and thwart the mechanisms that underlie HCMV activation and persistence in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mark F. Stinski for his insight and advice. We thank Magnus Wu and Chase Hardin for their assistance in the laboratory. We are also grateful to Feng Liu and Ushio Kikkawa for providing important reagents, to Natalie Leach for help with the PKC-delta dominant-negative experiment, and to members of the Stinski laboratory for helpful discussions of this work.

This work was supported by an American Heart Association grant-in-aid award and Veterans Affairs merit award to J.L.M.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 May 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham, I., K. E. Sampson, E. A. Powers, J. K. Mayo, V. A. Ruff, and K. L. Leach. 1991. Increased PKA and PKC activities accompany neuronal differentiation of NT2/D1 cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 28:29-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews, P. W. 1984. Retinoic acid induces neuronal differentiation of a cloned human embryonal carcinoma cell line in vitro. Dev. Biol. 103:285-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bani-Yaghoub, M., J. M. Felker, and C. G. Naus. 1999. Human NT2/D1 cells differentiate into functional astrocytes. Neuroreport 10:3843-3846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benedict, C. A., A. Angulo, G. Patterson, S. Ha, H. Huang, M. Messerle, C. F. Ware, and P. Ghazal. 2004. Neutrality of the canonical NF-kB-dependent pathway for human and murine cytomegalovirus transcription and replication in vitro. J. Virol. 78:741-750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biijli, K. M., F. Fazahl, M. Minhajuddin, and A. Rahman. 2008. Activation of Syk by protein kinase C-delta regulates thrombin-induced intercellular adhesion molecule-1 phosphorylation of RelA/p65. J. Biol. Chem. 283:14674-14684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blois, J. T., J. M. Mataraza, I. Mecklenbraüker, A. Tarakhovsky, and T. C. Chiles. 2004. B cell receptor-induced cAMP-response element-binding protein activation in B lymphocytes requires novel protein kinase Cdelta. J. Biol. Chem. 279:30123-30132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brose, N., and C. Rosenmund. 2002. Move over protein kinase C, you've got company: alternative cellular effectors of diacylglycerol and phorbol esters. J. Cell Sci. 115:4399-4411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caposio, P., A. Luganini, M. Bronzini, S. Landolfo, and G. Gribaudo. 2010. The Elk-1 and serum response factor binding sites in the major immediate-early promoter of the human cytomegalovirus are required for efficient viral replication in quiescent cells and compensate for inactivation of the NF-kappaB sites in proliferating cells. J. Virol. 84:4481-4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caposio, P., A. Luganini, G. Hahn, S. Landolfo, and G. Gribaudo. 2007. Activation of the virus-induced IKK/NF-kappaB signalling axis is critical for the replication of human cytomegalovirus in quiescent cells. Cell. Microbiol. 9:2040-2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chadalavada, R. S. V., J. Houldsworth, A. B. Olshen, G. J. Bosi, L. Studer, and R. S. K. Chaganti. 2005. Transcriptional program of bone morphogenetic protein-induced epithelial and smooth muscle differentiation of pluripotent human embryonal carcinoma cells. Funct. Integr. Genomics 5:59-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan, Y.-J., C.-J. Chiou, Q. Huang, and G. S. Hayward. 1996. Synergistic interactions between overlapping binding sites for the serum response factor and ELK-1 proteins mediate both basal enhancement and phorbol ester responsiveness of primate cytomegalovirus major immediate-early promoters in monocyte and T-lymphocyte cell types. J. Virol. 70:8590-8605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chomczynski, P., and N. Sacchi. 1987. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 162:156-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cinatl, J., S. Margraf, J.-U. Vogel, M. Scholz, J. Cinatl, and H. W. Doerr. 2001. Human cytomegalovirus circumvents NF-kB dependence in retinal pigment epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 167:1900-1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen, A., C. Brodie, and R. Sarid. 2006. An essential role of ERK signalling in TPA-induced reactivation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Gen. Virol. 87:795-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn, W., C. Chou, H. Li, R. Hai, D. Patterson, V. Stoic, H. Zhu, and F. Liu. 2003. Functional profiling of a human cytomegalovirus genome. J. Virol. 100:14223-14228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonczol, E., P. W. Andrews, and S. A. Plotkin. 1984. Cytomegalovirus replicates in differentiated but not in undifferentiated human embryonal carcinoma cells. Science 224:159-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodrum, F., C. T. Jordan, S. S. Terhune, K. High, and T. Shenk. 2004. Differential outcomes of human cytomegalovirus infection in primitive hematopoietic cell subpopulations. Blood 104:687-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gustems, M., E. Borst, C. A. Bendict, C. Perez, M. Messerle, P. Ghazal, and A. Angulo. 2006. Regulation of the transcription and replication cycle of human cytomegalovirus is insensitive to genetic elimination of the cognate NF-kappaB binding sites in the enhancer. J. Virol. 80:9899-9904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holden, N. S., P. E. Squires, M. Kaur, R. Bland, C. E. Jones, and R. Newton. 2008. Phorbol ester-stimulated NF-kB-dependent transcription: roles for isoforms on novel protein kinase C. Cell. Signal. 20:1338-1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunninghake, G. W., M. M. Monick, B. Liu, and M. F. Stinski. 1989. The promoter-regulatory region of the major immediate-early gene of human cytomegalovirus responds to T-lymphocyte stimulation and contains functional cyclic AMP-response elements. J. Virol. 63:3026-3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isomura, H., and M. F. Stinski. 2003. Effect of substitution of the human cytomegalovirus enhancer or promoter on replication in human fibroblasts. J. Virol. 77:3602-3614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isomura, H., M. F. Stinski, A. Kudoh, T. Daikoku, N. Shirata, and T. Tsurumi. 2005. Two Sp1/Sp3 binding sites in the major immediate-early proximal enhancer of human cytomegalovirus have a significant role in viral replication. J. Virol. 79:9597-9607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang, K., A. H. Apostolatos, T. Ghansah, J. E. Watson, T. Vickers, D. R. Cooper, P. K. Epling-Burnette, and N. A. Patel. 2008. Identification of a novel antiapoptotic human protein kinase C delta isoform, PKCdeltaVIII in NT2 cells. Biochemistry 47:787-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keller, M. J., D. G. Wheeler, E. Cooper, and J. L. Meier. 2003. Role of the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early promoter's 19-base-pair-repeat cAMP-response element in acutely infected cells. J. Virol. 77:6666-6675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keller, M. J., A. W. Wu, J. I. Andrews, P. W. McGonagill, E. E. Tibesar, and J. L. Meier. 2007. Reversal of human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early enhancer/promoter silencing in quiescently infected cells via the cyclic-AMP signaling pathway. J. Virol. 81:6669-6681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kikkawa, U., H. Matsuzaki, and T. Yamamoto. 2002. Protein kinase C delta (PKCdelta): activation mechanisms and functions. J. Biochem. 132:831-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Konishi, H., M. Tanaka, Y. Takemura, H. Matsuzaki, Y. Ono, U. Kikkawa, and Y. Nishizuka. 1997. Activation of protein kinase C by tyrosine phosphorylation in response to H2O2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:11233-11237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kucic, N., H. Mahmutefendic, and P. Lucin. 2005. Inhibition of protein kinases C prevents murine cytomegalovirus replication. J. Gen. Virol. 86:2153-2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurie, J. M., P. Brown, E. Salk, D. Scheinberg, M. Birrer, P. Deutsh, and E. Dmitrovsky. 1993. Cooperation between retinoic acid and phorbol ester enhances human teratocarcinoma differentiation. Differentiation 54:115-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwon, M. J., J. W. Soh, and C. H. Chang. 2006. Protein kinase C delta is essential to maintain CIITA gene expression in B cells. J. Immunol. 177:950-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lashmit, P., S. Wang, H. Li, H. Isomura, and M. F. Stinski. 2009. The CREB site in the proximal enhancer is critical for cooperative interaction with the other transcription factor binding sites to enhance transcription of the major intermediate-early genes in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells. J. Virol. 83:8893-8904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu, Z.-G., H. Liu, T. Yamaguchi, Y. Miki, and K. Yoshida. 2009. Protein kinase C delta activates RelA/p65 and nuclear factor-kappaB signaling in response to tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Cancer Res. 69:5927-5935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lundquist, C. A., J. L. Meier, and M. F. Stinski. 1999. A strong transcriptional negative regulatory region between the human cytomegalovirus UL127 gene and the major immediate early enhancer. J. Virol. 73:9032-9052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matin, M. M., J. R. Walsh, P. J. Gokhale, J. S. Draper, A. R. Bahrami, I. Morton, H. D. Moore, and P. W. Andrews. 2004. Specific knockdown of Oct4 and B2-microglobulin expression by RNA interference in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 22:659-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mayr, B., and M. Montminy. 2001. Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor CREB. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2:599-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meier, J. L. 2001. Reactivation of the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early regulatory region and viral replication in embryonal NTera2 cells: role of trichostatin A, retinoic acid, and deletion of the 21-base-pair repeats and modulator. J. Virol. 75:1581-1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meier, J. L., M. J. Keller, and J. J. McCoy. 2002. Requirement of multiple cis-acting elements in the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early distal enhancer for activation of viral gene expression and replication. J. Virol. 76:313-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meier, J. L., and M. F. Stinski. 1997. Effect of a modulator deletion on transcription of the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early genes in infected undifferentiated and differentiated cells. J. Virol. 71:1246-1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meier, J. L., and M. F. Stinski. 2006. Major immediate-early enhancer and its gene products, p. 151-166. In M. J. Reddehase (ed.), Cytomegaloviruses: molecular biology and immunology. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, United Kingdom.

- 40.Mendelson, M., S. Monard, P. Sissons, and J. Sinclair. 1996. Detection of endogenous human cytomegalovirus in CD34+ bone marrow progenitors. J. Gen. Virol. 77:3099-3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montminy, M. 1997. Transcriptional regulation by cyclic AMP. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66:807-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murphy, J. C., W. Fischle, E. Verdin, and J. H. Sinclair. 2002. Control of cytomegalovirus lytic gene expression by histone acetylation. EMBO J. 21:1112-1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Page, K., J. Li, L. Zhou, S. Iasvoyskaia, K. C. Corbit, J.-W. Soh, I. B. Weinstein, A. R. Brasier, A. Lin, and M. B. Hershenson. 2003. Regulation of airway epithelial cell NF-kB-dependent gene expression by protein kinase Cdelta. J. Immunol. 170:5681-5689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paola, D., C. Domenicotti, M. Nitti, A. Vitali, R. Borghia, D. Cottalasso, D. Zaccheo, P. Odetti, P. Strocchi, U. M. Marinari, M. Tabaton, and M. A. Pronzato. 2000. Oxidative stress induces increase in intracellular amyloid B-protein production and selective activation of BI and BII PKCs in NT2 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 268:642-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patel, N. A., S. S. Song, and D. R. Cooper. 2006. PKCdelta alternatively spliced isoforms modulate cellular apoptosis in retinoic acid-induced differentiation of human NT2 cells and mouse embryonic stem cells. Gene Expr. 13:73-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perkins, N. D. 2007. Integrating cell-signalling pathways with NF-kB and IKK function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Bio1. 8:49-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piontek, J., and R. Brandt. 2003. Differential and regulated binding of cAMP-dependent protein kinase and protein kinase C isoenzymes to gravin in human model neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 278:33970-38979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ravnskjaer, K., H. Kester, Y. Liu, X. Zhang, D. Lee, J. R. Yates, and M. Montiminy. 2007. Cooperative interactions between CBP and TORC2 confer selectivity to CREB target gene expression. EMBO J. 2880-2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Reeves, M. B., P. J. Lehner, J. G. Sissons, and J. H. Sinclair. 2005. An in vitro model for the regulation of human cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation in dendritic cells by chromatin remodeling. J. Gen. Virol. 86:2949-2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sands, W. A., and T. M. Palmer. 2008. Regulating gene transcription in response to cyclic AMP elevation. Cell. Signal. 20:460-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shaywitz, A. J., and M. E. Greenberg. 1999. CREB: a stimulus-induced transcription factor activated by a diverse array of extracellular signals. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68:821-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simon, C. O., C. K. Seckert, M. J. Reddehase, and N. K. A. Grzimek. 2006. Murine model of cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation: the silencing/desilencing and immune sensing hypothesis, p. 483-500. In M. J. Reddehase (ed.), Cytomegaloviruses: molecular biology and immunology. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, United Kingdom.

- 53.Sinclair, J., and P. Sissons. 2006. Latency and reactivation of human cytomegalovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 87:1763-1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sinzger, C., M. Kahl, K. Laib, K. Klingel, P. Reiger, B. Plachter, and G. Jahn. 2000. Tropism of human cytomegalovirus for endothelial cells is determined by a post-entry step dependent on efficient translocation to the nucleus. J. Gen. Virol. 81:3021-3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Slobbe-van Drunen, M. E., R. C. Vossen, F. M. Couwenberg, M. M. Hulsbosch, J. W. Heemskerk, M. C. van Dam-Mieras, and C. A. Bruggeman. 1997. Activation of protein kinase C enhances the infection of endothelial cells by human cytomegalovirus. Virus Res. 48:207-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stamminger, T., H. Fickenscher, and B. Fleckenstein. 1990. Cell type-specific induction of the major immediate-early enhancer of human cytomegalovirus by cAMP. J. Gen. Virol. 71:105-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]