Abstract

Immune responses and the components of protective immunity following norovirus infection in humans are poorly understood. Although antibody responses following norovirus infection have been partially characterized, T cell responses in humans remain largely undefined. In contrast, T cells have been shown to be essential for viral clearance of mouse norovirus (MNV) infection. In this paper, we demonstrate that CD4+ T cells secrete gamma interferon (IFN-γ) in response to stimulation with MNV virus-like particles (VLPs) after MNV infection, supporting earlier reports for norovirus-infected mice and humans. Utilizing this model, we immunized mice with alphavirus vectors (Venezuelan equine encephalitis [VEE] virus replicon particles [VRPs]) expressing Norwalk virus (NV) or Farmington Hills virus (FH) virus-like particles to evaluate T cell epitopes shared between human norovirus strains. Stimulation of splenocytes from norovirus VRP-immunized mice with overlapping peptides from complete libraries of the NV or FH capsid proteins revealed specific amino acid sequences containing T cell epitopes that were conserved within genoclusters and genogroups. Immunization with heterologous norovirus VRPs resulted in specific cross-reactive IFN-γ secretion profiles following stimulation with NV and FH peptides in the mouse. Identification of unique strain-specific and cross-reactive epitopes may provide insight into homologous and heterologous T cell-mediated norovirus immunity and provide a platform for the study of norovirus-induced cellular immunity in humans.

Norovirus infection is characterized by the induction of both humoral and cellular immune responses. Humoral immunity in humans following norovirus infection has been described in detail for a limited number of norovirus strains (8, 10, 12, 17, 18, 29). Humans mount specific antibody responses to the infecting strain, which bear complex patterns of unique and cross-reactive, yet undefined, epitopes to other strains within or across genogroups (23, 29). Short-term immunity following homologous norovirus challenge has been documented, but long-term immunity remains controversial (16, 25). Furthermore, no studies to date have demonstrated cross-protection following heterologous norovirus challenge (30). While some susceptible individuals can become reinfected with multiple norovirus strains throughout their lifetimes, the mechanism of short-term protection and the impact of previous exposures on susceptibility to reinfection remain largely unknown.

The role of T cells in controlling norovirus infection also remains largely undefined. A single comprehensive study detailing immune responses in genogroup II Snow Mountain virus-infected individuals revealed that CD4+ TH1 cells can be stimulated by virus-like particles (VLPs) to secrete gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) (17). Furthermore, heterologous stimulation from VLPs derived from different norovirus strains within but not across genogroups also induced significant IFN-γ secretion compared to that for uninfected individuals (17). A follow-up study with genogroup I Norwalk virus (NV)-infected individuals confirmed high T cell cross-reactivity within a genogroup as measured by IFN-γ secretion (18). Further, vaccination of humans with VLPs also results in short-term IFN-γ production (27).

Because norovirus infection studies in humans are confounded by previous exposure histories, the use of inbred mice maintained in pathogen-free environments allows for the study of norovirus immune responses in a naive background. While mice cannot be infected with human norovirus strains, VLP vaccines expressing norovirus structural proteins induce immune responses that can be measured and studied (14, 20). Mice immunized orally or intranasally with VLP vaccines in the presence of adjuvant similarly induced CD4+ IFN-γ responses in Peyer's patches and spleen (22, 26). Induction of CD8+ T cells and secretion of the TH2 cytokine IL-4 were separately noted; however, it is unclear if these responses were influenced by VLPs or the coadministered vaccine adjuvants (22, 26). Further, coadministration of alphavirus adjuvant particles with multivalent norovirus VLP vaccine, including or excluding mouse norovirus (MNV) VLPs, resulted in significantly reduced MNV loads following MNV challenge (21). Multivalent VLP vaccines induced robust receptor-blocking antibody responses to heterologous human strains not included in the vaccine composition (20, 21). Moreover, natural infection with MNV supports a role for T cell immunity in viral clearance and protection (5).

To advance our understanding of the scope of the cellular immune response within and between strains, we immunized mice with Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) virus replicon particles (VRPs) expressing norovirus VLPs derived from the Norwalk virus (GI.1-1968) (1) or Farmington Hills virus (FH) (GII.4-2002) (19) strains and analyzed splenocytes for cytokine secretion, epitope identification, and heterologous stimulation. The data presented here indicate that the major capsid proteins of genogroup I and II noroviruses contain robust T cell epitopes that cross-react with related strains in the mouse yet also occur within regions of known variation, especially among the GII.4 noroviruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

VRP immunization and MNV infection.

VRPs were produced as described by Harrington et al. (15). MNV-1 was produced as described by Chachu et al. (6). Six-week-old BALB/c mice (n = 4/experiment) were infected with 3 × 107 PFU MNV-1 orally as described previously (6) or were immunized with 2.5 × 106 VRP-expressing norovirus VLPs or a short noncoding sequence (null VRP) at days 0 and 21.

Splenocyte stimulation.

Spleens were harvested at 3 weeks postboost. Individual splenocytes were obtained by manual separation, filtration, and lysis of red blood cells. Cells were cultured at 1 × 106 cells/well in 96-well cell culture-treated plates in 100 μl complete RPMI medium containing one of the following: VLPs (1 μg/ml), individual NV or FH peptides or peptide pools (1 μg/ml/peptide), or no stimulant. Splenocytes were cultured for 48 h, at which time supernatants were harvested and stored at −80°C. VLPs were produced as described by LoBue et al. (20). Complete overlapping 15-mer (+5) peptide libraries spanning the entire NV (GI.1-1968) and FH (GII.4-2002) capsids and truncated stimulatory peptides were synthesized at the UNC peptide synthesis core facility. Lyophilized peptides were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS); insoluble peptides were further dissolved in 1:1 acetonitrile-PBS. CD4+ and CD8+ T cell depletions were performed following disruption using QuadroMACS magnetic bead separation (Miltenyi) per the manufacturer's instructions followed by stimulation as described above. Background levels often increased in concordance with the number of stimulatory peptides used in an assay.

IFN-γ EIA.

IFN-γ concentrations in splenocyte culture supernatants were determined by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (BD Pharmingen) per the manufacturer's instructions. t tests were performed to measure statistical differences between sample groups of two. All other statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Tukey posttest. In the figures, error bars indicate standard deviations and P values are indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Sequence alignments.

Stimulatory sequences identified using 15-mer peptides within the NV and FH capsids were aligned with sequences representing the entire VLP panel using Vector NTI software.

RESULTS

CD4+ T cells secret IFN-γ after homotypic VLP stimulation in MNV-infected mice.

There have been few reports on norovirus T cell cross-reactivity comparing norovirus strains, which can differ genetically by >50% in the capsid amino acid sequence (11). The ORF2 capsid gene of MNV-1 is roughly 40% identical to the NV and FH capsid genes. Given the near absence of human-derived T cell samples collected from characterized norovirus outbreaks and a tissue culture-adapted virus, we have cloned the antigenic ORF2 capsid genes from multiple norovirus strains into alphavirus vectors that, when expressed, form VLPs that can be simultaneously used as immunogens in vivo in mice and as antigenic reagents in vitro (15, 20).

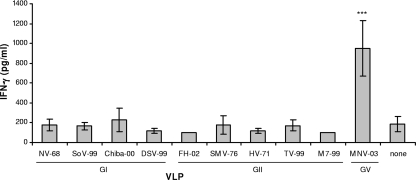

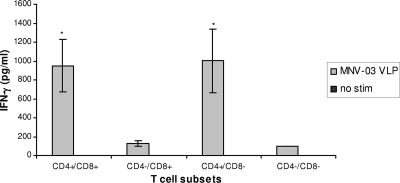

To begin to evaluate cross-reactivity among norovirus VLPs, we immunized mice with live MNV, harvested splenocytes, and stimulated splenocyte cultures with a panel of VLPs as described in Materials and Methods. VLP-stimulated culture supernatants contained elevated levels of IFN-γ following homologous MNV VLP stimulation but not heterologous human norovirus VLP stimulation (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). To identify the cellular source of IFN-γ secretion following infection with MNV, splenocytes were depleted of CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cells. Depleted cell suspensions were stimulated with MNV VLPs or unstimulated and cultured in parallel. Supernatants were then collected and IFN-γ secretion measured by EIA. Splenocytes depleted of CD4+ T cells secreted significantly less IFN-γ than CD8+-depleted splenocytes (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2), suggesting that IFN-γ secretion following MNV infection is also mediated by CD4+ cells. These observations of IFN-γ secretion by CD4+ T cells in response to a VLP within but not outside the infecting norovirus genogroup correspond with findings in humans infected with norovirus (17), indicating that the immune response to MNV infection in mice may correlate with the immune response to norovirus infection in humans.

FIG. 1.

Splenocyte stimulation with norovirus VLP panel following live MNV immunization. Splenocytes from mice immunized with live MNV GV-2003 were harvested and stimulated with each individual VLP at 1 μg/ml. After incubation for 48 h, culture supernatants were analyzed for IFN-γ by EIA (BD Pharmingen). Significant IFN-γ secretion occurred following MNV VLP stimulation (P < 0.001); human-derived VLPs did not elicit an IFN-γ response.

FIG. 2.

CD4+ and CD8+ T cell-depleted splenocyte stimulation. CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cells were depleted from splenocyte preparations from mice infected with MNV GV-2003 using marker-specific depleting antibodies conjugated to magnetic beads as directed by the manufacturer (Miltenyi). Depleted splenocytes (>90% pure) were stimulated with MNV VLPs for 48 h and supernatants analyzed for IFN-γ by EIA. CD4+/CD8−-depleted cultures and undepleted cultures secreted significantly more IFN-γ than CD4−/CD8+- and CD4−/CD8−-depleted cultures and unstimulated controls (P < 0.05).

Stimulation with overlapping peptide libraries facilitates identification of T cell epitopes.

Immunization of mice with VRPs containing norovirus ORF2 sequences results in an antinorovirus immune response characterized by production of broadly reactive, ligand-blocking antibody in both serum and the gut (15, 20, 21), which provides protection from MNV infection (21). These experiments suggest that human noroviruses share common antibody epitopes, as has been reported using sera from norovirus-infected humans (9, 13, 17, 18, 24). Thus, we chose to utilize this proven immunization approach to evaluate cross-reactive T cell epitopes in a manner similar to that used in studies evaluating antibody epitopes. We immunized BALB/c mice with VRP-NV, VRP-FH, or null VRP (VRP control) and harvested splenocytes. Splenocytes from unimmunized mice were treated in parallel. Peptide libraries representing NV GI.1-1968 and FH GII.4-2002 were sequentially divided into five overlapping pools, as shown in Table 1. Splenocytes were stimulated with individual peptide pools composed of 1 μg/ml each peptide and supernatants analyzed for IFN-γ by EIA.

TABLE 1.

Norwalk virus and Farmington Hills virus capsid peptide library sequences

| Domain or peptide pool | Amino acids |

|---|---|

| Capsid domainsa | |

| S | 1-125 |

| P1 | 126-278, 406-520 |

| P2 | 279-405 |

| NV peptide pools | |

| 1b | 1-105 |

| 2 | 91-215 |

| 3 | 201-305 |

| 4 | 291-405 |

| 5 | 391-525 |

| FH peptide pools | |

| 1 | 1-115 |

| 2 | 101-235 |

| 3 | 221-345 |

| 4 | 331-445 |

| 5b | 431-540 |

As described in reference 3.

The pool contains a stimulatory peptide(s).

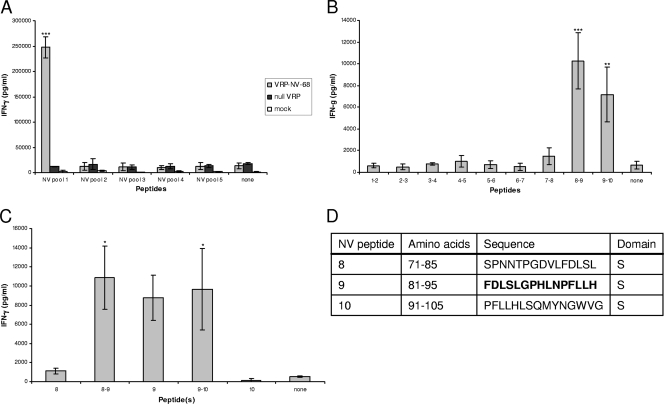

Splenocytes from VRP-NV-immunized mice secreted significantly higher levels of IFN-γ following stimulation with NV peptide pool 1 (amino acids 1 to 105 [Table 1]) than following stimulation with other NV peptide pools or controls (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3 A). Immunization with null VRP, which does not express a transgene from its internal promoter, did not result in splenocyte stimulation by NV peptides (Fig. 3A). Sequential overlapping peptide pools consisting of two peptides each from NV peptide pool 1 were then used to stimulate splenocytes from VRP-NV-immunized mice (Fig. 3B). Pools containing NV peptides 8-9 and 9-10 were positive for IFN-γ stimulation compared to all other overlapping peptides, suggesting an epitope in peptide 9 (P < 0.01). Individual and sequentially overlapping peptides flanking peptide 9 were used to confirm this finding (Fig. 3C). These data suggest that a stimulatory T cell epitope resides in the shell domain of the NV capsid within sequence FDLSLGPHLNPFLLH spanning amino acids 81 to 95 (Fig. 3D).

FIG. 3.

Norwalk capsid peptide stimulation. (A) Splenocytes from mice immunized with VRP-NV-GI.1-1968, null VRP, or no immunogen were stimulated with overlapping peptide pools of 10 to 11 peptides spanning the entire capsid and supernatants tested for IFN-γ. (B) Overlapping sets of peptides from stimulatory pools were used to stimulate splenocytes from VRP-NV-immunized mice to identify stimulatory peptides. (C) Individual and overlapping peptides were then used to identify peptides containing stimulatory sequences. (D) Stimulatory peptide sequences. Peptides in NV pool 1 (A) stimulated IFN-γ secretion significantly more than other pools (P < 0.001). Overlapping peptides 8-9 and 9-10 stimulated IFN-γ secretion significantly more than all other overlapping pairs (P < 0.01) (B) and more than peptide 8 or 10 alone (P < 0.05) (C).

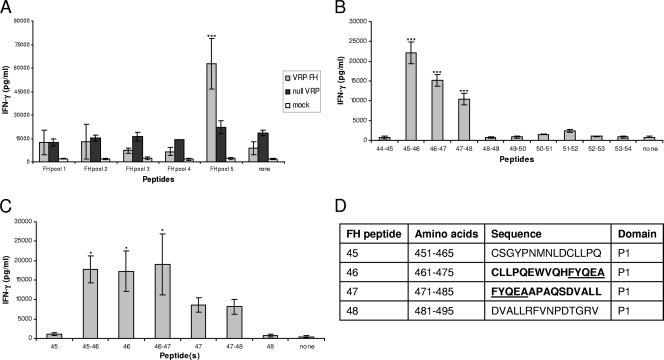

In contrast, splenocytes from VRP-FH-immunized mice secreted significantly higher levels of IFN-γ following stimulation with FH peptide pool 5 (amino acids 431 to 540 [Table 1]) than following stimulation with other FH peptide pools (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4 A). Cultures from mice immunized with null VRP or unimmunized controls were not stimulated by FH pool 5 (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4A). Sequentially overlapping pools and individual peptides within FH peptide pool 5 were then used to stimulate splenocytes from VRP-FH-immunized mice as described above (Fig. 4B and C). Overlapping peptides 45-46 induced significantly higher levels of IFN-γ than peptides 46-47 (P < 0.01) and all other overlapping groups (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4B). Peptides 46-47 and 47-48 also induced higher levels than all remaining overlapping groups (P < 0.001). Upon closer evaluation, stimulation with individual or overlapping peptides containing peptide 46 induced significant IFN-γ responses compared to individual peptide 45 or 48 (P < 0.05) but not peptide 47 (Fig. 4C). Stimulation with individual or overlapping peptides containing peptide 47 also induced IFN-γ secretion that was elevated above that with peptide 45 or 48 stimulation, but this was not significant. Together, these data suggest that peptides 46 and 47 spanning amino acids 461 to 485 of sequence CLLPQEWVQHFYQEAAPAQSDVALL in the P1 capsid domain contain one or two distinct T cell stimulatory epitopes (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 4.

Farmington Hills capsid peptide stimulation. (A) Splenocytes from mice immunized with VRP-FH-GII.4-2002, null VRP, or no immunogen were stimulated with overlapping peptide pools of 10 to 11 peptides spanning the entire capsid and supernatants tested for IFN-γ. (B) Overlapping sets of peptides from stimulatory pools were used to stimulate splenocytes from VRP-NV-immunized mice to identify stimulatory peptides. (C) Individual and overlapping peptides were then used to identify peptides containing stimulatory sequences. (D) Stimulatory peptide sequences, with overlapping regions underlined. IFN-γ was significantly higher following stimulation with FH pool 5 than with the other pools (P < 0.001) (A). Overlapping peptides 45-46 induced increased IFN-γ secretion compared to peptides 46-47 (P < 0.01) and all other overlapping peptides (P < 0.001) (B). Peptides 46-47 and 47-48 induced increased IFN-γ secretion compared to all other overlapping peptides (P < 0.001) (B). Stimulation with individual and overlapping peptides containing peptide 46 were significantly higher than that with peptide 45 or 48 alone (P < 0.05) (C).

Stimulatory sequences are conserved within genoclusters and genogroups.

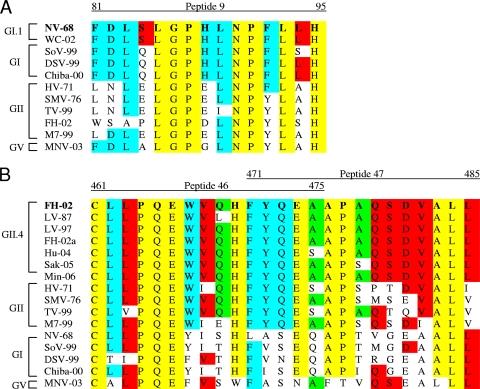

To determine if the identified stimulatory sequences within NV and FH are conserved across additional norovirus strains, we performed alignments of corresponding sequences from our panel of VLPs (Fig. 5). Alignments revealed that sequences from two NV-like strains within the GI.1 genocluster were completely conserved (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, the stimulatory sequence was also highly conserved (86.7%) across all other GI sequences tested but was only 46.7% conserved when aligned with GII sequences. Stimulatory FH sequences were highly conserved (91.7%) within the GII.4 genocluster among seven time-ordered strains analyzed. The sequentially evolved LV 1997, FH 2002a, and FH 2002 sequences (19), as well as the recently isolated Minerva 2006 sequence (4), were identical. A single amino acid difference was noted with other contemporary isolates. However, sequences of additional strains within GII (60%) or in GI (40%) were not as highly conserved (Fig. 5b).

FIG. 5.

Alignments of stimulatory NV and FH capsid peptide sequences. Identified stimulatory sequences within the NV (A) and FH (B) capsids were aligned with corresponding sequences from other GI and GII strains. Yellow, amino acids completely conserved across human genogroups; blue, amino acids completely conserved within genogroup; red, amino acids completely conserved within genocluster; green, variable.

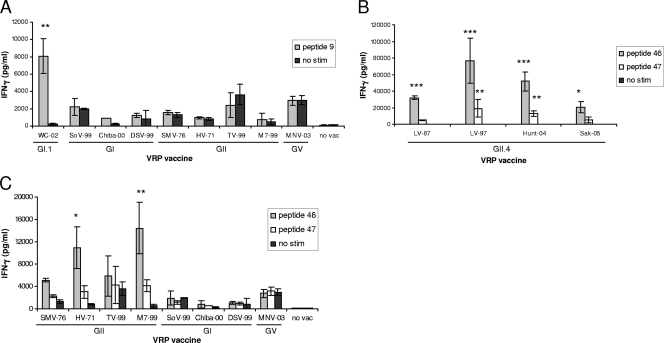

To directly evaluate stimulatory-sequence cross-reactivity among norovirus strains, groups of mice were individually immunized with VRPs expressing VLPs from NV GI.1-1968, FH GII.4-2002, heterologous GI, heterologous GII, or MNV strains, and splenocytes were stimulated with NV peptide 9, FH peptide 46, or FH peptide 47. Mice immunized with VRP-WC, a GI.1-2001 (18) NV-like VLP having an identical corresponding sequence to NV peptide 9, had strong IFN-γ responses to peptide 9 stimulation that were significantly higher than those in all other immunization groups (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6 A). In contrast, immunization with heterologous GI strains in genoclusters different from that of NV, as well as GII and MNV strains, elicited no IFN-γ responses following peptide 9 stimulation (Fig. 6A). These results suggest that although sequences corresponding to peptide 9 within heterologous GI appear to be highly conserved, the stimulatory epitope requires complete identity for cross-reactivity, which is maintained only within the GI.1 genocluster. Because only the serine (S) residue at position 84 is different in NV and several heterologous GI sequences, S may be an integral residue required for epitope recognition (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 6.

Stimulatory sequence cross-reactivity among norovirus strains. Following immunization with a panel of VRPs, splenocytes were stimulated with NV GI.1-1968 peptide 9 (A) or FH GII.4-2002 peptide 46 or 47 (B and C) or unstimulated and were measured for IFN-γ secretion by EIA. Stimulation with NV peptide 9 elicited significantly higher IFN-γ responses in WC (GI.1) immune splenocytes than other groups (P < 0.01) (A). Stimulation with FH 46 elicited significantly higher IFN-γ responses in all GII.4 immune groups (B) than in all non-GII.4 immune groups (C) (Sak, P < 0.05; other GII.4 groups, P < 0.001), and M7 and HV (GII) immune splenocytes elicited higher responses than GI immune splenocytes (P < 0.01 and 0.05, respectively) (C). Stimulation with FH peptide 47 elicited significantly higher IFN-γ responses in LV97 and Hunt (GII.4) groups than non-GII groups (P < 0.01).

Cross-reactive secretion of IFN-γ in response to FH peptide 46 and 47 stimulation was very robust following immunization with heterologous GII.4 strains LV 1987, LV 1997, Hunter 2004, and Sakai 2005 (Fig. 6B) and was significantly higher than IFN-γ levels induced following non-GII.4 immunization in most groups (Fig. 6C) (P < 0.05 to 0.001). Additionally, IFN-γ levels following stimulation in heterologous GII-immune cultures M7 (P < 0.01) and HV (P < 0.05) were significantly higher than those in GI- or MNV-immune cultures, where IFN-γ secretion was absent (Fig. 6c). Unstimulated control splenocyte cultures from each immunization group did not secrete significant amounts of IFN-γ (Fig. 6A to C). Together, these data indicate that GII strains within and outside the GII.4 genocluster maintain epitope integrity with various amounts of sequence variation.

Deletion of N-terminal and C-terminal residues of stimulatory sequences reveal likely NV and FH T cell epitopes.

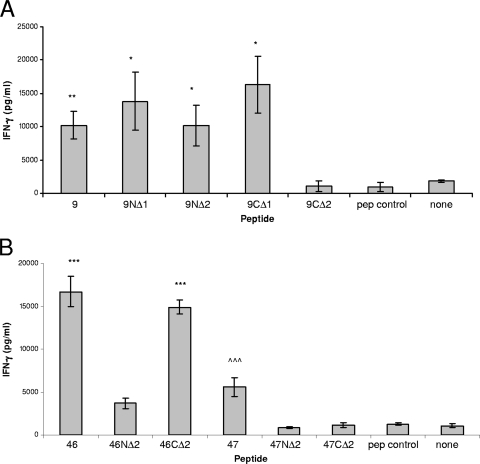

Truncated peptides of the original stimulatory NV9 sequence lacking one or two residues from the N terminus (9NΔ1 and 9NΔ2) or one or two residues from the C terminus (9CΔ1 and 9CΔ2) were synthesized and used to stimulate splenocytes from VRP-NV-immunized mice. Likewise, truncated FH46 and FH47 peptides lacking two residues from each terminus were synthesized (46NΔ2, 46CΔ2, 47NΔ2, and 47CΔ2) and used to stimulate splenocytes from VRP-FH-immunized mice. IFN-γ levels following stimulation with 9NΔ1, 9NΔ2, and 9CΔ1 were not different from levels following stimulation with the uncompromised NV9 peptide, (Fig. 7 A). On the contrary, stimulation with 9CΔ2 resulted in IFN-γ secretion below background levels. These data show that from the original NV peptide sequence (FDLSLGPHLNPFLLH), the T cell epitope is contained within the sequence LSLGPHLNPFLL for BALB/c mice.

FIG. 7.

Norwalk and Farmington Hills virus T cell epitope identification. Splenocytes from NV GI.1-1968-immunized (A) and FH GII.4-2002-immunized (B) mice were stimulated with N- and C-terminally truncated strain-specific peptides to identify stimulatory epitopes. NV peptides 9 (P < 0.01) and 9NΔ1, 9NΔ2, and 9CΔ1 (P < 0.05) induced significantly more IFN-γ secretion than 9CΔ2 and controls (A). FH peptides 46 and 46CΔ2 induced significantly more IFN-γ secretion than 46NΔ2 and controls (P < 0.001), and FH peptide 47 induced significantly more IFN-γ secretion than 47NΔ2, 47CΔ2, and controls (P < 0.001) (B).

Stimulation of FH-immune splenocyte cultures with 46NΔ2 resulted in significantly lower levels of IFN-γ secretion, whereas stimulation with 46CΔ2 did not affect IFN-γ secretion compared to stimulation with the original FH peptide 46 (Fig. 7B). Stimulation with both 47NΔ2 and 47CΔ2 resulted in significantly decreased IFN-γ secretion compared to stimulation with full-length peptide. These data suggest that the epitope sequence contained within peptide 46 includes residues CLLPQEWVQHFYQ. The secondary epitope within peptide 47 cannot be deduced from these data; however, we can conclude that at least one residue contiguous with each terminus is required for epitope integrity in BALB/c mice. We can also conclude that peptides 46-47 likely contain two independent epitopes rather than one overlapping epitope due to maintained stimulation following deletion of the C-terminal residues of peptide 46 and loss of activity following deletion of the N-terminal residues of peptide 47, which are equivalent residues and unlikely to have different phenotypes in mutual epitopes.

DISCUSSION

The components of protective immunity in human norovirus infection are unknown. Understanding the mechanisms governing norovirus immunity is not only essential for development of efficacious norovirus vaccines and therapeutics but likely required for understanding differential outcomes of viral pathogenesis following repeat infections. Two vaccine strategies for norovirus immune induction are currently being evaluated: (i) oral or intranasal administration of VLPs and (ii) VRP expression of VLPs in vivo following subcutaneous administration. Oral administration of VLP vaccines in humans, while safe and immunogenic, has been shown to induce very weak humoral and cellular immune responses to norovirus compared to norovirus infection and likely will require adjuvant enhancements (27). In contrast, alphavirus VRPs induce strong mucosal, cellular, and humoral immune responses to the expressed transgene, including norovirus VLPs in mice (7, 15, 28), and, importantly, have been shown to be safe and effective in humans (2).

The emergence of literature documenting T cell responses following norovirus infection in humans or immunization in mice suggests that the cellular immune response is a potentially important component in norovirus vaccine design. Chachu et al. (5) recently showed that both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells participate in viral clearance mechanisms following MNV infection. Findings from our group and others specifically support CD4+ TH1 T cells as likely candidates responsible for IFN-γ secretion in response to norovirus challenge, including MNV challenge (17, 22, 26, 27) (Fig. 2). The TH1 cytokine IFN-γ was elevated in splenocyte culture supernatants following stimulation with norovirus peptides (Fig. 3, 6, and 7). Previous work reported by our group also showed that VRPs induce IgA and IgG responses at mucosal surfaces that can block virus-receptor ligand interactions (20). Together these data suggest that norovirus vaccination with VRPs may be a promising strategy for individuals in environments with a high risk of exposure, such as hospitals and primary care facilities.

To facilitate vaccine design and begin to decipher complex cross-reactive responses, we have begun to characterize T cell responses to homologous and heterologous norovirus capsid peptides following VRP immunization in the mouse. Although it is unlikely that specific murine and human T cell epitopes are conserved across species, we can determine murine-specific epitopes contained within human norovirus strains and their relative conservation across genetically related norovirus strains as a surrogate model. This information will likely be useful in determining if previous exposure to or vaccination against heterologous strains can confer T cell-mediated protection upon subsequent challenge and in informing future human studies.

Unknown preexposure histories in humans can skew cross-reactivity profiles and are highly variable between individuals, and thus we used norovirus-naive mice to provide a clearer view of T cell cross-reactivity between strains. Mice immunized with live MNV mount a specific homotypic response to MNV VLPs but did not mount cross-genogroup reactive IFN-γ responses when stimulated with heterologous human-derived VLPs, mimicking results found in norovirus-infected humans. Our results indicate that T cell responses following VRP vaccination to one norovirus strain are cross-reactive to heterologous norovirus peptides when sequence homology is highly conserved (Fig. 6). These data support previous findings by Lindesmith et al. (17) showing that peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from humans infected with a GII.2 SMV strain cross-reacted to stimulation with VLPs from GII.1 HV strain but much less so to GI VLPs. Peptides can be used not only to determine cross-reactivity between strains but also to identify specific T cell epitopes, making them particularly advantageous immunogens. Stimulation with peptides resulted in robust IFN-γ secretion from identifiable pools (Fig. 3A and 4A); however, stimulatory sequences were located in different domains of the capsid for NV and FH. The amino acid sequence FDLSLGPHLNPFLLH located in the shell domain was found to be stimulatory to NV-immune splenocytes, and the sequence CLLPQEWVQHFYQEAAPAQSDVALL located in the P1 domain was found to be stimulatory to FH-immune splenocytes. The identified sequences are unlikely to contain residues important for receptor binding (19).

Alignments of capsid sequences of additional GI.1 and GII.4 strains to the stimulatory sequences within NV and FH, respectively, revealed high homology to additional strains (100% and 91.7%, respectively) (Fig. 5). Peptide stimulation of splenocytes following immunization with heterologous strains within these genoclusters resulted in variable levels of cross-reactive IFN-γ responses (Fig. 6A and B). For example, mice immunized with GII.4 strains LV97 and Hunter, which represent evolutionarily distinct strains that emerged immediately before and after the FH strain, respectively (19), mounted higher cross-reactive responses to FH peptides than mice immunized with their more evolutionarily distant GII.4 counterparts LV87 and Sakai. Together, these results suggest that T cell epitopes are conserved within the GII.4 genocluster and are likely to activate a memory T cell response upon subsequent challenge with genetically related strains. However, we note that some epitopes may be evolving over time in genoclusters under high evolutionary pressure, such as the GII.4 cluster in human populations. These data suggest that future human challenge studies and/or outbreak investigations should consider evaluating homotypic and heterotypic memory T cell responses against time-ordered and more distant genocluster strains. In contrast, additional GI sequences outside the GI.1 genocluster were also highly conserved (86.7%) compared to the stimulatory NV sequence, but splenocytes from other GI VRP-vaccinated animals did not mount cross-reactive responses to the NV peptide. These BALB/c data are in contrast to recent human data demonstrating GI VLP cross-reactive T cell responses in NV-infected humans and likely represent restrictions specific for the BALB/c major histocompatibility complex (MHC), which recognized only a single NV stimulatory peptide. Alternatively, conserved epitopes may exist in one or more other GI genoclusters not evaluated in our analyses. In comparison, human T cell responses represent an accumulated memory after multiple lifetime exposures, and cells were stimulated with intact VLPs as opposed to peptides, allowing for stimulation of the maximum variety of cells. Heterologous GII sequences outside the GII.4 genocluster were less highly conserved (60%) to the stimulatory FH sequence; however, splenocyte cultures following heterologous GII immunization induced cross-reactive responses to the FH peptides. These findings suggest that specific residues within stimulatory sequences are likely to elicit robust responses and may not be dependent on the context of the entire sequence. Furthermore, epitopes and cross-reactivity outcomes are likely to be variable and strain dependent within and across genogroups. Sequences were not conserved across genogroups, which is supported by our findings that stimulatory NV and FH peptides did not stimulate splenocytes immune to strains outside the respective genogroups, and similar findings have been noted for humans (17, 18).

Defining specific epitopes for T cell activation on distinct norovirus capsids will reveal unknown antigenic and immunogenic relationships among norovirus strains. Using overlapping peptide libraries, we were able to experimentally identify specific stimulatory peptides containing putative T cell epitopes. Synthesis of truncated peptides for use in stimulatory assays allowed for identification of required residues for epitope identification. Epitopes for T cell activation in mice may be different from those in humans; however, the mechanism(s) of protection following infection is likely similar. The newly developed mouse norovirus challenge model will allow continued investigation into the effect of the T cell response following homologous or heterologous norovirus exposure as well as a system in which to evaluate the efficacy of preventative therapies triggering T cell-specific responses. These preliminary studies will provide previously unattainable answers to questions that can bridge important issues in human medicine.

Acknowledgments

We thank Martha Collier and Nancy Davis of the Carolina Vaccine Institute for VRP production and Victoria Madden and C. Robert Bagnell, Jr., of the Microscopy Services Laboratory, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, for expert technical support.

This work was supported by grant AI 056351-06. Anna LoBue was supported by a UNC Graduate School Dissertation Completion Fellowship.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 June 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baric, R. S., et al. 2002. Expression and self-assembly of Norwalk virus capsid protein from Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicons. J. Virol. 76:3023-3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein, D. I., et al. 2009. Randomized, double-blind, phase 1 trial of an alphavirus replicon vaccine for cytomegalovirus in CMV seronegative adult volunteers. Vaccine 28:484-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertolotti-Ciarlet, A., et al. 2002. Structural requirements for the assembly of Norwalk virus-like particles. J. Virol. 76:4044-4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cannon, J. L., et al. 2009. Herd immunity to GII.4 noroviruses is supported by outbreak patient sera. J. Virol. 83:5363-5374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chachu, K. A., et al. 2008. Immune mechanisms responsible for vaccination against and clearance of mucosal and lymphatic norovirus infection. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chachu, K. A., et al. 2008. Antibody is critical for the clearance of murine norovirus infection. J. Virol. 82:6610-6617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis, N. L., et al. 2002. Alphavirus replicon particles as candidate HIV vaccines. IUBMB Life 53:209-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erdman, D. D., G. W. Gary, and L. J. Anderson. 1989. Serum immunoglobulin A response to Norwalk virus infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:1417-1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farkas, T., et al. 2003. Homologous versus heterologous immune responses to Norwalk-like viruses among crew members after acute gastroenteritis outbreaks on 2 US Navy vessels. J. Infect. Dis. 187:187-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray, S. F., and M. R. Evans. 1993. Dose-response in an outbreak of non-bacterial food poisoning traced to a mixed seafood cocktail. Epidemiol. Infect. 110:583-590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green, K. Y., et al. 2002. A predominant role for Norwalk-like viruses as agents of epidemic gastroenteritis in Maryland nursing homes for the elderly. J. Infect. Dis. 185:133-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hale, A. D., et al. 1998. Homotypic and heterotypic IgG and IgM antibody responses in adults infected with small round structured viruses. J. Med. Virol. 54:305-312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hale, A. D., et al. 2000. Identification of an epitope common to genogroup 1 “Norwalk-like viruses.” J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1656-1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrington, P. R., et al. 2002. Binding of Norwalk virus-like particles to ABH histo-blood group antigens is blocked by antisera from infected human volunteers or experimentally vaccinated mice. J. Virol. 76:12335-12343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrington, P. R., et al. 2002. Systemic, mucosal, and heterotypic immune induction in mice inoculated with Venezuelan equine encephalitis replicons expressing Norwalk virus-like particles. J. Virol. 76:730-742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson, P. C., et al. 1990. Multiple-challenge study of host susceptibility to Norwalk gastroenteritis in US adults. J. Infect. Dis. 161:18-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindesmith, L., et al. 2005. Cellular and humoral immunity following Snow Mountain virus challenge. J. Virol. 79:2900-2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindesmith, L. C., et al. 2010. Heterotypic humoral and cellular immune responses following Norwalk virus infection. J. Virol. 84:1800-1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindesmith, L. C., et al. 2008. Mechanisms of GII.4 norovirus persistence in human populations. PLoS Med. 5:e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LoBue, A. D., et al. 2006. Multivalent norovirus vaccines induce strong mucosal and systemic blocking antibodies against multiple strains. Vaccine 24:5220-5234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LoBue, A. D., et al. 2009. Alphavirus-adjuvanted norovirus-like particle vaccines: heterologous, humoral, and mucosal immune responses protect against murine norovirus challenge. J. Virol. 83:3212-3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicollier-Jamot, B., et al. 2003. Molecular cloning, expression, self-assembly, antigenicity, and seroepidemiology of a genogroup II norovirus isolated in France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3901-3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noel, J. S., et al. 1997. Correlation of patient immune responses with genetically characterized small round-structured viruses involved in outbreaks of nonbacterial acute gastroenteritis in the United States, 1990 to 1995. J. Med. Virol. 53:372-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parker, T. D., et al. 2005. Identification of genogroup I and genogroup II broadly reactive epitopes on the norovirus capsid. J. Virol. 79:7402-7409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parrino, T. A., et al. 1977. Clinical immunity in acute gastroenteritis caused by Norwalk agent. N. Engl. J. Med. 297:86-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Periwal, S. B., et al. 2003. A modified cholera holotoxin CT-E29H enhances systemic and mucosal immune responses to recombinant Norwalk virus-virus like particle vaccine. Vaccine 21:376-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tacket, C. O., et al. 2003. Humoral, mucosal, and cellular immune responses to oral Norwalk virus-like particles in volunteers. Clin. Immunol. 108:241-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson, J. M., et al. 2006. Mucosal and systemic adjuvant activity of alphavirus replicon particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:3722-3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Treanor, J. J., et al. 1993. Subclass-specific serum antibody responses to recombinant Norwalk virus capsid antigen (rNV) in adults infected with Norwalk, Snow Mountain, or Hawaii virus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:1630-1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wyatt, R. G., et al. 1974. Comparison of three agents of acute infectious nonbacterial gastroenteritis by cross-challenge in volunteers. J. Infect. Dis. 129:709-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]