Abstract

Despite substantial efforts to control H5N1 avian influenza viruses (AIVs), the viruses have continued to evolve and cause disease outbreaks in poultry and infections in humans. In this report, we analyzed 51 representative H5N1 AIVs isolated from domestic poultry, wild birds, and humans in China during 2004 to 2009, and 21 genotypes were detected based on whole-genome sequences. Twelve genotypes of AIVs in southern China bear similar H5 hemagglutinin (HA) genes (clade 2.3). These AIVs did not display antigenic drift and could be completely protected against by the A/goose/Guangdong/1/96 (GS/GD/1/96)-based oil-adjuvanted killed vaccine and recombinant Newcastle disease virus vaccine, which have been used in China. In addition, antigenically drifted H5N1 viruses, represented by A/chicken/Shanxi/2/06 (CK/SX/2/06), were detected in chickens from several provinces in northern China. The CK/SX/2/06-like viruses are reassortants with newly emerged HA, NA, and PB1 genes that could not be protected against by the GS/GD/1/96-based vaccines. These viruses also reacted poorly with antisera generated from clade 2.2 and 2.3 viruses. The majority of the viruses isolated from southern China were lethal in mice and ducks, while the CK/SX/2/06-like viruses caused mild disease in mice and could not replicate in ducks. Our results demonstrate that the H5N1 AIVs circulating in nature have complex biological characteristics and pose a continued challenge for disease control and pandemic preparedness.

The highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza viruses that emerged over a decade ago in southern China have evolved into over 10 distinct phylogenetic clades based on their hemagglutinin (HA) genes. The viruses have spread to over 63 countries and to multiple mammalian species, including humans, resulting in 498 cases of infection and 294 deaths by 6 May 2010 according to the World Health Organization (WHO) (http://www.who.int). To date, none of the different H5N1 clades has acquired the ability to consistently transmit among mammalian species. The currently circulating H5N1 viruses are unique in that they continue to circulate in avian species. All previous highly pathogenic H5 and H7 viruses have naturally “burned out” or were stamped out because of their high pathogenicity in domestic poultry. While there is growing complacency about the potential of H5N1 “bird flu” to attain consistent transmissibility in humans and develop pandemicity, it is worth remembering that we have no knowledge of the time that it took the 1918 Spanish, the 1957 Asian, the 1968 Hong Kong, and the 2009 North American pandemics to develop their pandemic potentials. We may therefore currently be witnessing in real time the evolution of an H5N1 pandemic influenza virus.

H5N1 avian influenza viruses (AIVs) were first detected in sick geese in Guangdong province in 1996, and both nonpathogenic and highly pathogenic (HP) H5N1 viruses were described (18). In 1997, H5N1 reassortant viruses that derived the HA gene from A/goose/Guangdong/1/96 (GS/GD/1/96)-like viruses and the other genes from H6N1 and/or H9N2 viruses caused lethal outbreaks in poultry and humans in Hong Kong (6, 7). Since then, long-term active surveillance of influenza viruses in domestic poultry has been performed, and multiple subtypes of influenza viruses have been detected in chickens and ducks in China (16, 19, 37). H5N1 influenza viruses have been repeatedly detected in apparently healthy ducks in southern China since 1999 (4, 13) and were also detected in pigs in Fujian province in 2001 and 2003 (39).

Since the beginning of 2004, there have been significant outbreaks of H5N1 avian influenza virus infection involving multiple poultry farm flocks in more than 20 provinces in China (2). H5N1 viruses resulted in the deaths of millions of domestic poultry, including chickens, ducks, and geese, as the result of infection or of culling and the deaths of thousands of wild birds (5, 20). Thirty-eight human cases of HP H5N1 infection with 25 fatalities have been associated with direct exposure to infected poultry (WHO; http://www.who.int). Since 2004, the vaccination of domestic poultry has been used for the control of HP H5N1 influenza virus in China. While this strategy has been effective at reducing the incidence of HP H5N1 in poultry and at markedly reducing the number of human cases, it is impossible to vaccinate every single bird due to the enormous poultry population. Outbreaks of H5N1 influenza virus still continue to occur in poultry although at a reduced frequency.

A previous study by Smith et al. reported that a “Fujian-like” H5N1 influenza virus emerged in late 2005 and predominated in poultry in southern China (26). Those authors suggested that vaccination may have facilitated the selection of the “Fujian-like” sublineage. Here, we analyzed 51 representative H5N1 viruses that were isolated from wild birds, domestic poultry, and humans from 2004 to 2009 in China and described their genetic evolution and antigenicity profiles. Our results indicate that H5N1 influenza viruses in southern China, including the “Fujian-like” viruses, are complicated reassortants, which could be well protected against by GS/GD/1/96 virus-based vaccines. We documented the emergence of the latest variant of H5N1 (A/chicken/Shanxi/2/06 [CK/SX/2/06]) that broke through existing poultry vaccines. We show that this variant is less pathogenic in mice and ducks than the earlier strains and propose that the variant was not selected by the use of vaccines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses.

The 51 H5N1 viruses used in this study were isolated from the samples that were sent to the National Avian Influenza Reference Laboratory for the diagnosis of suspected cases of avian influenza virus infection during 2004 to 2009 in China (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). All experiments with the H5N1 isolates were performed in a biosafety level 3 laboratory facility, and animal experiments were performed in HEPA-filtered isolators.

Genetic and phylogenetic analyses.

Viral RNA was extracted with the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and was reverse transcribed. PCR amplification was performed by using segment-specific primers (primer sequences are available upon request). The PCR products were purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and sequenced by using the CEQ DTCS-Quick Start kit with a CEQ 8000 DNA sequencer (Beckman Coulter). Sequence data were compiled with the SEQMAN program (DNASTAR, Madison, WI), and phylogenetic analyses were carried out with the PHYLIP program of the CLUSTALX software package (version 1.81) using a neighbor-joining algorithm. Bootstrap values of 1,000 were used.

Antigenic analyses.

Antigenic analyses were performed by hemagglutinin inhibition (HI) tests using chicken antisera generated against the tested viruses. To generate the antisera, 6-week-old specific-pathogen-free (SPF) chickens were injected with 0.5 ml of oil emulsion-inactivated vaccine derived from the selected viruses, and sera were collected at 3 weeks after injection. We used 0.5% chicken erythrocytes in the HI assay.

Animal experiments.

All animal studies were approved according to the national guidelines by the Review Board of Harbin Veterinary Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

Groups of eight 6-week-old female BALB/c mice (Beijing Experimental Animal Center, Beijing, China) were lightly anesthetized with CO2 and inoculated intranasally (i.n.) with 106.0 50% egg infective doses (EID50) of H5N1 influenza virus in a volume of 50 μl. Three of the eight mice were killed on day 3 postinoculation (p.i.) for virus titration in the lungs, kidneys, spleen, and brain. The remaining five mice were monitored daily for weight loss and mortality. The 50% mouse lethal dose (MLD50) was determined for viruses that caused lethal infection of mice by the i.n. inoculation of groups of five mice. The MLD50 was calculated by the method of Reed and Muench (23).

Groups of eight 4-week-old SPF ducks were intranasally inoculated with 106 EID50 of H5N1 influenza virus in a volume of 0.1 ml. Three of eight ducks were killed on day 3 p.i., and organs were collected for virus titration. The remaining five ducks were observed for 2 weeks for disease, death, and serum conversion. Swabs from all of the ducks were collected on days 3, 5, and 7 for the detection of virus shedding.

Vaccination and challenge study of chickens.

An oil-adjuvanted inactivated vaccine produced with the seed virus Re-1, which is a reassortant virus, generated by reverse genetics, containing the modified HA and neuraminidase (NA) genes of GS/GD/1/96 virus and the six internal genes of A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (PR8) virus (31), had been used in poultry since 2004 (3). Recombinant Newcastle disease virus (NDV) strain LaSota, expressing the HA gene of the GS/GD/1/96 virus, was constructed as previously described (11) and used as a bivalent vaccine to protect chickens from Newcastle disease virus and H5N1 avian influenza virus infection (3). To evaluate the protective efficacy of these two vaccines, 3-week-old SPF chickens were vaccinated with 0.3 ml of the H5N1 inactivated vaccine containing 2.8 μg of the HA protein (31) via intramuscular injection or vaccinated i.n. with 106 EID50 of a recombinant NDV vaccine. Three weeks after vaccination, chickens were challenged with 105 EID50 of different H5N1 influenza viruses. Oropharyngeal and cloacal swabs of the chickens were collected for virus titration on days 3 and 5 postchallenge (p.c.), and chickens were observed for signs of disease or death for 2 weeks p.c.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences analyzed in this study are available at the GenBank database under accession numbers HM172069 to HM172484 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

RESULTS

Molecular and phylogenetic analysis.

Between 2004 and 2009, H5N1 viruses caused over 100 outbreaks of HP influenza virus infection in poultry and wild birds in China. To understand the genetic relationships, 51 representative viruses isolated from chickens, ducks, geese, wild birds, and humans were sequenced and compared with 10 representative viruses that were previously reported (4, 5, 35, 36).

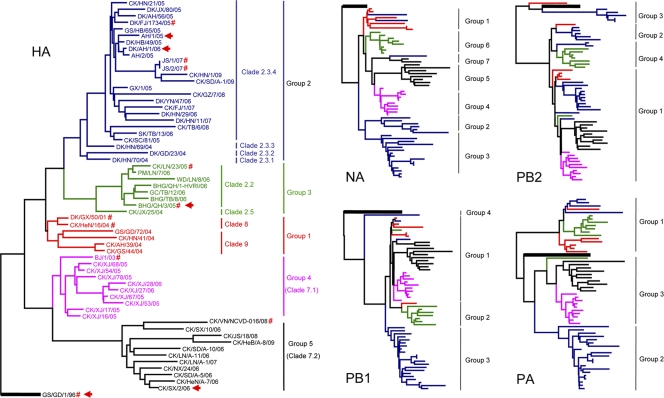

The HA genes of the 61 isolates were divided phylogenetically into five groups (Fig. 1). Group 1 contained six viruses, with five of them being representative viruses isolated during the 2004 outbreak. All of them shared over 98% homology and grouped with the previously reported A/duck/Guangxi/50/01 (DK/GX/50/01) virus (4). We included the previously reported clade 8 and 9 H5N1 viruses (1, 33) in this group, as their intergroup homology is over 98%. The HA gene of the group 2 viruses (clade 2.3) included 25 viruses isolated mainly from southern China (Fig. 1). This group was isolated mainly from ducks but also includes chicken, goose, and human isolates. Eight viruses formed group 3 (clade 2.2), with one virus being the representative virus isolated from chickens in Liaoning in 2005, one virus being isolated from poultry outbreaks in 2004, and six viruses being isolated from wild birds in Qinghai, Tibet, and Liaoning provinces during 2005 to 2006 (Fig. 1). Group 4 (clade 7.1) contained nine poultry viruses and one human isolate. The nine poultry viruses were isolated from chickens in Xinjiang province during 2005 to 2006, and the HA genes of these viruses shared 97.4% to 98.5% homology with the HA gene of A/Beijing/1/03 (BJ/1/03) (H5N1) virus, a human representative strain of the clade 7 viruses (1, 33). Group 5 included 11 viruses: one virus was isolated from Vietnam (22), and 10 viruses were isolated from chickens in six provinces in northern China and one province in southern China during 2006 to 2009. These viruses, represented by A/chicken/Shanxi/2/2006 (CK/SX/2/06), represent a novel group of H5N1 viruses not previously characterized; their HA genes share less than 95% homology with the group 1, group 2, and group 3 viruses and less than 97% homology with the group 4 viruses. The closest sequence to that of the CK/SX/2/06-like viruses from previously available databases is the BJ/1/03 virus, which has only 96.5% nucleotide sequence identity. A previous report (1) designated the BJ/1/03 and CK/SX/2/06 viruses as the representative strains of clade 7; however, in our analysis, these two viruses were mapped into two different groups, and we therefore designated the group 4 and group 5 viruses as clade 7.1 and clade 7.2, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic analyses of the H5N1 viruses isolated from 2004 to 2009 in China. The phylogenetic trees were generated with the PHYLIP program of the CLUSTALX software package (version 1.81). The five trees were generated based on the following sequences: HA nucleotides (nt) 29 to 1732, NA nt 21 to 1730, PB2 nt 28 to 2307, PB1 nt 25 to 2298, and PA nt 25 to 2175. The phylogenetic tree of HA was rooted to A/mallard/Denmark/64650/03 (H5N7), the NA phylogenetic tree was rooted to A/green-winged teal/Ohio/72/99 (H1N1), and the PB2, PB1, and PA phylogenetic trees were rooted to A/Memphis/1/90 (H3N2). The colors of the viruses in the NA, PB2, PB1, and PA trees match with those used in the HA tree. Abbreviations: BHG, bar-headed goose; CK, chicken; DK, duck; GS, goose; GC, great cormorant; SK, shrike; AH, Anhui; FJ, Fujian; GD, Guangdong; GX, Guangxi; HB, Hubei; HN, Hunan; HeB, Hebei; HeN, Henan; JX, Jiangxi; LN, Liaoning; NX, Ningxia; QH, Qinghai; SD, Shandong; SX, Shanxi; TB, Tibet; XJ, Xinjiang. Sequences labeled with a red “#” in the HA tree were downloaded from the available databases. Viruses labeled with a red arrow were selected for antiserum generation.

The neuraminidase (NA) genes of all of the viruses tested had a 20-amino-acid deletion in the NA stalk (residues 49 to 68). The NA genes of these viruses formed seven groups (Fig. 1, and see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). H5N1 viruses isolated in 2004 formed groups 1, 2, and 3 and contained the viruses isolated in poultry in southern China from 2004 to 2007. Groups 4, 5, and 6 contained the viruses isolated from chickens in Xinjiang (XJ chicken-like), from chickens in other northern provinces (SX chicken-like), and from wild birds (QH wild bird-like), respectively. Group 7 contained three viruses that were isolated in 2008 and 2009. The homology of the genes within groups is over 98%, and the homology of the genes is less than 97% between the groups.

The PB2 genes of these viruses formed four groups (Fig. 1, and see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Group 1 contained most viruses that were isolated from domestic poultry in 2004 and the viruses isolated from chickens in northern China from 2006 to 2009, including the XJ chicken-like viruses and SX chicken-like viruses. Groups 2 and 3 contained viruses causing outbreaks in domestic poultry in southern China during 2005 to 2007. Group 4 contained viruses causing outbreaks in wild birds in Qinghai and Tibet during 2005 to 2006 and two viruses isolated from chickens in southern China in 2008. The PB2 genes of the viruses in group 3 shared less than 92% homology with those in the other three groups, and the homology among the other three groups was between 95% and 97%. All of the PB2 genes of the group 4 viruses have a lysine at position 627 that is conserved among influenza viruses that have adapted to mammals (30) and is associated with the high virulence of H5N1 viruses in mice (12).

The PB1 genes of these H5N1 viruses were classified into four groups (Fig. 1, and see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Group 1 contained most of the viruses that were isolated from domestic poultry in southern China between 2004 and 2009 and the XJ chicken-like viruses. Groups 2 and 3 contained the QH wild bird-like viruses and the SX chicken-like viruses, respectively. The PB1 gene of A/chicken/Guizhou/7/08 (CK/GZ/7/08) formed group 4 by itself.

The PA genes of these viruses were divided into three groups. Group 1 contained most of the viruses isolated in 2004 and QH wild bird-like viruses. Group 2 contained viruses isolated mainly from domestic poultry in southern China from 2004 to 2009. The XJ chicken- and SX chicken-like viruses formed group 3 (Fig. 1, and see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

The NP genes of all of these viruses shared over 97% homology and were considered one lineage, although they formed different forks in the phylogenetic tree (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The M genes of the viruses formed three groups (Fig. S1). Group 1 contained three viruses isolated in 2004 and the QH wild bird-like viruses. Group 2 contained viruses from chickens in northern China from 2005 to 2009, and the remaining viruses formed group 3. The NS genes of these viruses could be divided into two groups (Fig. S1). Group 1 contained the QH wild bird-like viruses and a few viruses isolated in 2004, and the remaining viruses formed group 2.

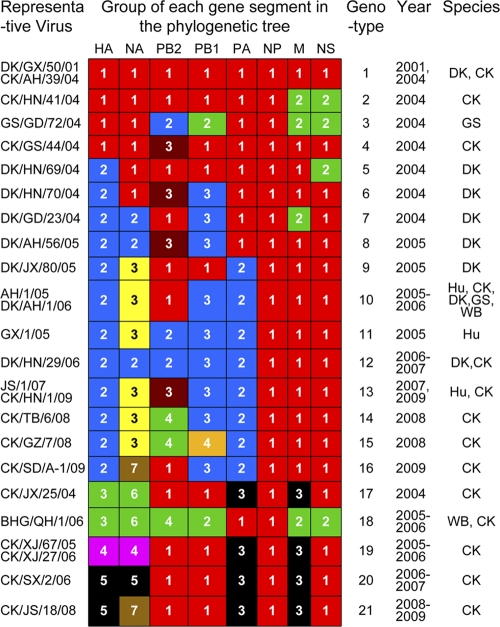

On the basis of genomic diversity, the viruses investigated in this study were divided into 21 genotypes (Fig. 2, and see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Genotype 1 represents the majority of H5N1 viruses that were isolated from influenza virus outbreaks in 2004, while genotypes 2 through 7 and genotype 17 contain viruses from individual outbreaks in 2004. Genotypes 8 through 15, containing the HA gene of clade 2.3, represent the viruses isolated from domestic poultry from 2005 to 2009 in southern China, and genotype 16 is the only virus detected from northern China that bears the HA gene of clade 2.3. It is noteworthy that 17 genotypes (genotypes 1 to 17) were originally detected in domestic poultry, mainly from waterfowl, in southern China. The wild bird viruses included in this study are genetically similar to our previously reported genotype C virus that was detected in Qinghai Lake in 2005 (5), and they were designated genotype 18 (Fig. 2). Genotype 19 represents viruses isolated in chickens in Xinjiang, and genotypes 20 and 21 represent viruses isolated in other provinces in northern China. The viruses in genotypes 10, 11, 13, 18, and 19 are associated with human infections in China and other countries (1, 33).

FIG. 2.

Genotypic evolution of the H5N1 viruses isolated in China from 2004 to 2009. The eight gene segments are indicated at the top of each bar. The number in each bar shows the group of genes indicated in Fig. 1 and Fig. S1 in the supplemental material.

Studies with mice.

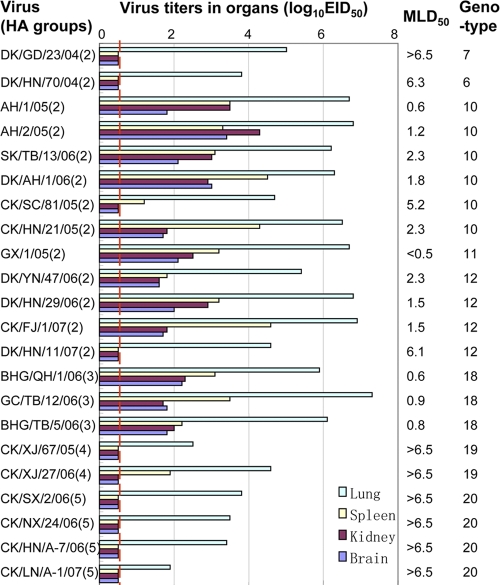

In our previous study of the viruses isolated from ducks in Southern China during 1999 to 2002, we observed an increasing level of pathogenicity in mice with the progression of time (4). Maines et al. also reported previously that H5N1 viruses exhibited increased lethality over time in ferrets (21). To investigate the virulences of the viruses isolated in recent years in China, we selected and tested 22 viruses from eight different genotypes (genotypes 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 18, 19, and 20) in mice. We found that 9 of 13 viruses isolated from domestic poultry in southern China, including the viruses of genotypes 6, 7, 10, 11, and 12, replicated systemically and killed mice at a very low dosage (50% minimal lethal dose [MLD50] of <3 log10 EID50) (Fig. 3). The DK/GD/23/04 (genotype 7), DK/HN/70/04 (genotype 6), CK/SC/81/05 (genotype 10), and DK/HN/11/07 (genotype 12) virus replicated well in the lungs of mice but were not detected in the kidneys or brains of the animals. These four viruses killed mice only at a high dosage (MLD50 of >5.2 log10 EID50) (Fig. 3). All three wild bird viruses (genotype 18 viruses) were highly lethal in mice (MLD50 of <1 log10 EID50). However, all six other viruses isolated from chickens in northern China (genotypes 19 and 20) replicated only in the lungs and did not kill any mice, even at the highest inoculation dosage (MLD50 of >6.5 log10 EID50) (Fig. 3, and see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

FIG. 3.

Replication and virulence of H5N1 influenza viruses in mice. Virus replication was tested as described in Materials and Methods. The data shown are the mean titers for three mice. A value of 0.5 was assigned if the virus was not detected from the undiluted sample. The MLD50 is shown as the log10 EID50. Genotypes were determined on the basis of the diversity of the gene nucleotide sequences, as described in the legends of Fig. 1 and 2. The red dashed line indicates the lower limit of detection.

Studies with ducks.

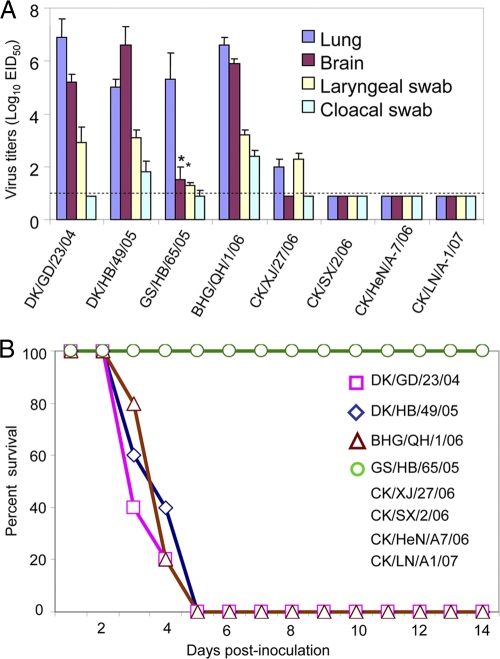

The H5N1 viruses that were isolated from apparently healthy ducks did not kill any ducks in the laboratory setting even though they were shed from the trachea or the cloaca (4). Since late 2003, however, H5N1 viruses have caused disease and deaths in ducks in multiple countries (27, 29). To understand the virulence in ducks of the viruses that were isolated in China in recent years, specific-pathogen-free (SPF) ducks were intranasally inoculated (106 EID50 in a 0.1-ml volume) with eight representative viruses isolated from different species, geographic locations, and time periods.

As shown in Fig. 4, three viruses, two viruses from ducks and one virus from bar-headed goose, could replicate to high titers in the lungs and brains of ducks. These viruses were shed through tracheae and/or cloacae after being intranasally inoculated (Fig. 4 A) and killed all of the inoculated ducks within 5 days postinoculation (p.i.) (Fig. 4B). The GS/HB/65/05 virus replicated in the lungs of ducks as well as the duck and wild bird viruses, but the virus titer in the brain was significantly lower than that observed for the inoculated duck and wild bird viruses. Low titers of this virus were detected on day 3 p.i. (Fig. 4A). The CK/XJ/27/06 virus replicated in the lung at lower titers and was shed through the trachea, but virus replication and shedding were not detected for any ducks that were inoculated with three SX/CK/2/06-like viruses isolated from chickens in northern China (Fig. 4A). All of the ducks inoculated with GS/HB/65/05, CK/XJ/27/06, CK/SX/2/06, CK/HeN/A7/06, and CK/LN/A1/06 stayed healthy and survived during the 2-week observation period (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Replication and virulence of H5N1 influenza viruses in ducks. (A) Viral titers and shedding in ducks on day 3 p.c. Data shown are means ± standard deviation. For statistical purposes, a value of 0.9 was assigned if virus was not detected from the undiluted sample. *, P < 0.01 compared with the titers in the corresponding samples in the DK/GD/23/04, DK/HB/43/05, and BHG/QH/1/06 virus-inoculated ducks. (B) Death pattern for ducks inoculated with different H5N1 influenza viruses. The dashed line indicates the lower limit of detection.

Antigenic analysis.

Antisera, generated in SPF chickens or ferrets, to the selected H5N1 viruses and two monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) derived from GS/GD/1/96 and CK/SX/2/06 viruses, respectively, were used for antigenic analyses by hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assays with 0.5% chicken erythrocytes. As indicated in Table 1, the antisera generated in chickens against GS/GD/1/96, DK/AH/1/06, and BHG/QH/3/05 cross-reacted well with most viruses that were isolated from domestic poultry in southern China, the viruses from wild birds (genotype 18), and the viruses from chickens in Xinjiang (genotype 19). The HI titers of these viruses, however, were 2- to 8-fold lower than the homologous titers. It is worth noting that the antisera of these three viruses reacted poorly with the viruses isolated from chickens in northern China (genotype 20). The antisera derived from CK/SX/2/06 reacted well with the genotype 20 viruses but poorly with all other viruses. Their heterologous HI titers were >8- to 16-fold lower than the homologous HI titers (Table 1). Unlike the chicken antisera generated against the DK/AH/1/06 virus, which cross-reacted with most of the viruses, ferret antisera against AH/1/05 reacted poorly with the CK/SX/2/06-like viruses and with the BHG/QH/3/05 virus, suggesting that the oil adjuvant antigen may have induced greater cross-reactivity. MAb DD7, derived from GS/GD/1/96, did not react with the chicken viruses from northern China, including the genotype 20 and 21 viruses, but reacted with other viruses with various titers. MAb SCiC1, derived from CK/SX/2/06 virus, reacted with the majority of the tested viruses but not with the wild bird viruses (genotype 18) and the CK/FJ/1/07 virus (Table 1). These results suggest that the H5N1 influenza viruses circulating in China are antigenically different. The viruses isolated from chickens in several provinces in northern China (genotypes 20 and 21) especially exhibited severe antigenic drift.

TABLE 1.

Antigenic analysis of H5N1 avian influenza viruses isolated in China

| Virus (HA gene group) | HA cladeg | Genotypeg | HI antibody titere |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antiserum |

MAb |

||||||||

| GS/GD/1/96a | DK/AH/1/06a | BHG/QH/3/05a | CK/SX/2/06a | AH/1/05b | DD7c | SCiC1d | |||

| GS/GD/1/96 | 0 | NA | 512 | 512 | 256 | 32 | 80 | 1,024 | 128 |

| DK/AH/1/06 (2) | 2.3.4 | 10 | 256 | 512 | 256 | 32 | 320 | 512 | 128 |

| BHG/QH/3/05 (3) | 2.2 | 18 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 16 | 20 | 64 | <2 |

| CK/SX/2/06 (5) | 7.2 | 20 | 8 | 32 | 16 | 512 | <10 | <2 | 512 |

| AH/1/05 (2) | 2.3.4 | 10 | 128 | 512 | 512 | 32 | 640 | 512 | 32 |

| DK/GD/23/04 (2) | 2.3.2 | 7 | 64 | 256 | 256 | 32 | — | 256 | 32 |

| DK/HN/69/04 (2) | 2.3.3 | 5 | 64 | 256 | 256 | 32 | — | 256 | 32 |

| DK/HN/70/04 (2) | 2.3.1 | 6 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 32 | — | 512 | 32 |

| DK/HN/21/05 (2) | 2.3.4 | 10 | 64 | 256 | 256 | 32 | — | 256 | 32 |

| DK/HB/49/05 (2) | 2.3.4 | 10 | 64 | 256 | 128 | 32 | — | 512 | 32 |

| AH/2/05 (2) | 2.3.4 | 10 | 128 | 512 | 256 | 32 | 640 | 512 | 16 |

| GX/1/05 (2) | 2.3.4 | 11 | 128 | 512 | 512 | 64 | 1,280 | 512 | 32 |

| CK/FJ/1/07 (2) | 2.3.4 | 12 | 64 | 256 | 128 | 32 | — | 64 | <2 |

| CK/TB/6/08 (2) | 2.3.4 | 14 | 32 | 256 | 256 | 16 | 320 | — | <2 |

| CK/GZ/7/08 (2) | 2.3.4 | 15 | 64 | 512 | 512 | 32 | 320 | — | <2 |

| CK/HN/1/09 (2) | 2.3.4 | 13 | 64 | 256 | 256 | 32 | 320 | — | <2 |

| CK/LN/23/05 (3) | 2.2 | 18 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 16 | — | 64 | <2 |

| BHG/QH/1/06 (3) | 2.2 | 18 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 16 | — | 64 | <2 |

| GC/TB/12/06 (3) | 2.2 | 18 | 128 | 128 | 256 | 8 | — | 64 | <2 |

| CK/XJ/67/05 (4) | 7.1 | 19 | 64 | 256 | 128 | 64 | — | <2 | 256 |

| CK/XJ/27/06 (4) | 7.1 | 19 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 64 | — | <2 | 256 |

| CK/NX/24/06 (5) | 7.2 | 20 | 8 | 32 | 8 | 256 | <10 | <2 | 256 |

| CK/HeN/7/06 (5) | 7.2 | 20 | 16 | 32 | 16 | 256 | <10 | <2 | 256 |

| CK/LN/A1/07 (5) | 7.2 | 20 | 8 | 32 | 8 | 256 | <10 | <2 | 256 |

| CK/SD/A5/06 (5) | 7.2 | 20 | 8 | 32 | 16 | 128 | <10 | <2 | 128 |

| CK/JS/18/08 (5) | 7.2 | 21 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 64 | <10 | — | <2 |

| CK/SH/10/01(H9N2)f | NA | NA | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | — | — | — |

| NDV (LaSota strain)f | NA | NA | <2 | <2 | <2 | <2 | — | — | — |

Antisera were generated by vaccinating SPF chickens with the oil-emulsified inactivated vaccine derived from the indicated viruses.

Antisera were generated in ferrets.

The MAb was generated from GS/GD/1/96 virus.

The MAb was generated from CK/SX/2/06 virus.

—, not done. Homologous titers are shown in boldface type.

An H9N2 virus and a Newcastle disease virus were used as negative antigen controls.

NA, not applicable.

Protective efficacy of the H5N1 vaccines used in China.

China is one of the countries that use vaccines to control H5N1 influenza virus in poultry. An inactivated vaccine containing the HA and NA genes of the GS/GD/1/96 virus and internal genes from the A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (PR8) virus was developed by reverse genetics and has been used in the field since 2004 (31). Recombinant NDVs containing the HA genes of H5N1 influenza virus were also generated as bivalent live, attenuated vaccines against both NDV and avian influenza virus infection in poultry (11). The bivalent vaccine that contains the HA gene of GS/GD/1/96 has been used in the field since 2006. The GS/GD/1/96-based vaccines induced cross-reactive antisera (Table 1) and completely protected chickens from challenges against the viruses from southern China (clade 2.3) and the viruses from wild birds (clade 2.2) (Table 2). However, the GS/GD/1/96-based antisera reacted poorly with the CK/SX/2/06-like virus. To evaluate whether the GS/GD/1/96-based vaccine could provide protection against the CK/SX/2/06-like viruses, we performed challenge studies with chickens. As shown in Table 2, virus shedding was detected on day 5 postchallenge (p.c.) in 4 of 20 chickens that were inoculated with the inactivated vaccine and in 12 of 20 chickens that received the recombinant NDV vaccine. Only 80% and 40% of chickens vaccinated with inactivated vaccine and recombinant NDV, respectively, survived during the 2-week observation period after challenge. All of the chickens in the control group died before day 4 p.c. (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Protective efficacies of Chinese vaccines against different H5N1 virusesa

| Challenge virus (HA group [clade]) | Vaccine | No. of swabs with virus shedding/total no. of swabs (mean log10 EID50 ± SD)b |

No. of surviving animals/total no. of animals | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 3 |

Day 5 |

|||||

| Oropharyngeal | Cloacal | Oropharyngeal | Cloacal | |||

| BHG/3/05 (3 [2.2]) | Inactivated | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 10/10 |

| Recombinant NDV | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 10/10 | |

| Control | 10/10 (3.0 ± 0.4) | 10/10 (2.7 ± 1.0) | — | — | 0/10 | |

| AH/1/05 (2 [2.3.4]) | Inactivated | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 10/10 |

| Recombinant NDV | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 10/10 | |

| Control | 10/10 (2.4 ± 0.6) | 10/10 (1.7 ± 0.6) | 3/3 (1.4 ± 0.1) | 3/3 (1.8 ± 0.4) | 0/10 | |

| DK/HN/21/05 (2 [2.3.4]) | Inactivated | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 10/10 |

| Recombinant NDV | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 10/10 | |

| Control | 10/10 (3.3 ± 0.4) | 10/10 (3.4 ± 1.0) | — | — | 0/10 | |

| CK/SX/2/06 (5 [7.2]) | Inactivated | 0/20 | 0/20 | 3/20 (1.7 ± 0.3)c | 4/20 (1.5 ± 0.2)c | 16/20 |

| Recombinant NDV | 0/20 | 0/20 | 11/20 (2.0 ± 0.4)c | 12/20 (1.9 ± 0.2)c | 8/20 | |

| Control | 20/20 (2.9 ± 0.6) | 20/20 (1.9 ± 0.5) | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/20 | |

Three-week-old SPF chickens were used for this study.

—, chickens died in that group.

The titers shown are the means ± standard deviations of the chickens that actually shed virus.

DISCUSSION

Despite substantial efforts to control infection of poultry, H5N1 viruses have continued to evolve and spread. The viruses have caused outbreaks in poultry in more than 60 countries and have caused human infections in 15 countries, which have resulted in 294 fatalities by 6 May 2010 according to the WHO (http://www.who.int). Here, we analyzed H5N1 influenza viruses isolated from domestic poultry, wild birds, and humans from 2004 to 2009 in China. Our results demonstrate that these H5N1 influenza viruses formed 21 different genotypes and exhibited distinct virulence in ducks and in a mammalian mouse model. We also determined that the H5N1 influenza viruses that emerged in chickens in northern China in 2006 had antigenically drifted and could not be protected efficiently by the GS/GD/1/96 virus-derived vaccines used in China.

Our results demonstrated that the viruses from domestic poultry, mainly from ducks, in southern China are complicated reassortants. The HA (group 2, clade 2.3), NP, M (except the DK/GD/23/04 virus), and NS (except the DK/HN/69/04 virus) genes of the viruses isolated from 2004 to 2009 in southern China (genotypes 5 to 16) are quite similar (Fig. 2), but their NA, PB2, PB1, and PA genes show significant diversity. This suggests that multiple subtypes of influenza viruses may have actively cocirculated in waterfowl in this region and that reassortment among different viruses frequently occurred. Smith et al. previously reported that a “Fujian-like” H5N1 virus dominated in southern China (26). However, our data indicate that the viruses detected in China bearing the HA of clade 2.3.4 viruses are complicated reassortants. We cannot determine which of these viruses dominates over the others. The HA genes of the clade 2.3 viruses were detected as early as 2004, and although these viruses exhibited some degree of antigenic drift compared with the index virus GS/GD/1/96, they could still be completely protected by the GS/GD/1/96-based vaccines. The continued circulation of these groups of viruses in southern China may have resulted from unqualified vaccination coverage in waterfowl, especially in ducks, and not as a result of vaccination selection as was pointed out previously by Smith et al. (26).

We reported previously that the viruses isolated from the outbreak in wild birds in Qinghai Lake consisted of four genotypes, and the dominant genotype, represented by the BHG/QH/3/05 virus, derived the HA, NA, and NP genes from A/CK/JX/25/04-like viruses (5). Our current results suggest that BHG/QH/3/05-like viruses are likely a reassortant of A/CK/JX/25/04-like viruses, a GS/GD/72/04-like virus, and an unknown virus that contributed the PB2 gene containing a lysine at position 627. This PB2 gene was detected in CK/TB/6/08 and CK/GZ/7/08 viruses that were isolated from chickens in the live-bird markets in Tibet and Guizhou in 2008. The lysine at position 627 in PB2 is conserved in human viruses and is associated with the high virulence of H5N1 viruses in mice (12) and the transmission of influenza viruses in mammals (28). The BHG/QH/3/05-like viruses were not detected in poultry in China after 2005; however, they were repeatedly detected in wild birds or domestic poultry in other countries in Europe, Africa, and Asia (8, 15, 25, 32) and were reported to be detected in pikas in the Qinghai Lake area in 2007 (38). These widely distributed viruses bear two known genetic markers in the PB2 and HA genes that have been proven to be critical for the transmission of H5N1 influenza viruses in mammalian hosts (10, 28) and represent a clear pandemic potential.

The CK/SX/2/06-like viruses were first detected in chickens from the Shanxi province in northern China that were vaccinated with GS/GD/1/96-based inactivated avian influenza virus vaccines. The viruses then spread to several other provinces in northern China, including Ningxia, Henan, Shandong, and Liaoning provinces. The origin of these viruses is still unclear. Their degree of antigenic drift may easily connect their emergence as a result of vaccination selection; however, genomic analyses confirmed that the CK/SX/2/06-like viruses are reassortants with new HA, NA, and PB1 genes that were newly introduced into poultry in China. Viruses with an HA gene similar to that of CK/SX/2/06-like viruses were also detected in chickens in Vietnam in 2008 (22). The sequences of the NA gene and of the internal genes of these viruses from Vietnam are not available; therefore, it is unknown if they have genomes similar to those of the CK/SX/2/06-like viruses or if the viruses acquired the HA gene from a similar ancestor. The limited replication of the CK/SX/2/06-like viruses in mice and ducks suggests that these viruses have not been transmitted into or adapted to other species. However, it is concerning that the CK/SX/2/06-like viruses reacted poorly with the antisera generated from other viruses, and therefore, it is important to include viruses from this clade for vaccine development for the possibility of an H5N1 influenza virus pandemic.

The virulence of influenza virus is a polygenic trait. Several amino acids in the PB2, NS1, and M1 genes have been proven to be associated with the virulence of avian influenza viruses in a mammalian host (9, 13, 17, 24, 34). All of the viruses of genotypes 10 and 12 have the same amino acids in positions that were reported to be important for the virulence of H5N1 influenza virus in mice (9, 13, 17, 24, 34); however, it is interesting that the virulences of the CK/SC/81/05 virus of genotype 10 and of the DK/HN/11/07 virus of genotype 12 were over 1,000-fold lower in mice than those of other viruses of the same genotypes (Fig. 3). These viruses could therefore be used as model viruses to explore new genetic determinants for the virulence of H5N1 viruses in mammals.

Vaccination is a major strategy used in China for the control of H5N1 avian influenza virus. The H5 inactivated vaccine has been proven to be efficacious in chickens, ducks, and geese (14, 31). The present study demonstrated that the GS/GD/1/96 virus-based vaccine could protect against different H5N1 viruses isolated in China, except the CK/SX/2/06-like viruses. An inactivated vaccine containing the modified HA and NA genes of the CK/SX/2/06 virus has been developed and used in several provinces in northern China since 2006 (3). The surface genes of a clade 2.3.4 virus, DK/AH/1/06, were used to construct the PR8 reassortant and recombinant Newcastle disease virus vaccine seed strains, and these seed viruses were used to replace the GS/GD/1/96 virus-based strains for vaccine production in the middle of 2008 (2). Although vaccine efficacy has been confirmed in both laboratory and field tests (11, 31), and the vaccine strain has been updated in a timely manner, the control of H5N1 avian influenza virus by vaccination still faces different challenges in different avian species. Older ducks are more resistant to H5N1 viruses than are younger ducks (31). Therefore, many adult ducks were not vaccinated and may still serve as a reservoir for the virus. The continued circulation of H5N1 viruses in southern China may then be a result of low vaccination coverage rather than the viruses having undergone a mutation that has allowed them to escape vaccine-induced protection.

In summary, we fully analyzed 51 H5N1 influenza viruses isolated from 2004 to 2009 in China. We characterized the genetic and biological complexity of H5N1 AIVs and provided important information for a more comprehensive understanding of H5N1 AIV evolution. The multiple genotypes of viruses detected in southern China imply that the environmental factors in that area may have favored the generation of reassortants. It is therefore worrisome that these lethal H5N1 AIVs may have more opportunities to acquire the ability to efficiently transmit among humans. Moreover, the emergence of antigenically drifted CK/SX/06-like viruses poses a challenge for influenza virus pandemic preparedness. Clearly, there is a critical need for the continued surveillance of poultry and for regularly updated control measures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gloria Kelly for editing the manuscript and Nancy Cox for providing the ferret antisera against H5N1 influenza virus.

This work was supported by Chinese National Natural Science Foundation grant 30825032; Chinese National Key Basic Research Program (973) grants 2010CB534000, 2005CB523005, and 2005CB523200; and by grants 2006BAD06A05 and 2009ZX10004-214 from the Chinese National S&T Plan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 June 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdel-Ghafar, A. N., T. Chotpitayasunondh, Z. Gao, F. G. Hayden, D. H. Nguyen, M. D. de Jong, A. Naghdaliyev, J. S. Peiris, N. Shindo, S. Soeroso, and T. M. Uyeki. 2008. Update on avian influenza A (H5N1) virus infection in humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 358:261-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen, H. 2009. H5N1 avian influenza in China. Sci. China C Life Sci. 52:419-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, H., and Z. Bu. 2009. Development and application of avian influenza vaccines in China. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 333:153-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, H., G. Deng, Z. Li, G. Tian, Y. Li, P. Jiao, L. Zhang, Z. Liu, R. G. Webster, and K. Yu. 2004. The evolution of H5N1 influenza viruses in ducks in southern China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:10452-10457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, H., Y. Li, Z. Li, J. Shi, K. Shinya, G. Deng, Q. Qi, G. Tian, S. Fan, H. Zhao, Y. Sun, and Y. Kawaoka. 2006. Properties and dissemination of H5N1 viruses isolated during an influenza outbreak in migratory waterfowl in western China. J. Virol. 80:5976-5983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chin, P. S., E. Hoffmann, R. Webby, R. G. Webster, Y. Guan, M. Peiris, and K. F. Shortridge. 2002. Molecular evolution of H6 influenza viruses from poultry in Southeastern China: prevalence of H6N1 influenza viruses possessing seven A/Hong Kong/156/97 (H5N1)-like genes in poultry. J. Virol. 76:507-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Jong, J. C., E. C. Claas, A. D. Osterhaus, R. G. Webster, and W. L. Lim. 1997. A pandemic warning? Nature 389:554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ducatez, M. F., C. M. Olinger, A. A. Owoade, Z. Tarnagda, M. C. Tahita, A. Sow, S. De Landtsheer, W. Ammerlaan, J. B. Ouedraogo, A. D. Osterhaus, R. A. Fouchier, and C. P. Muller. 2007. Molecular and antigenic evolution and geographical spread of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses in western Africa. J. Gen. Virol. 88:2297-2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabriel, G., B. Dauber, T. Wolff, O. Planz, H. D. Klenk, and J. Stech. 2005. The viral polymerase mediates adaptation of an avian influenza virus to a mammalian host. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:18590-18595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao, Y., Y. Zhang, K. Shinya, G. Deng, Y. Jiang, Z. Li, Y. Guan, G. Tian, Y. Li, J. Shi, L. Liu, X. Zeng, Z. Bu, X. Xia, Y. Kawaoka, and H. Chen. 2009. Identification of amino acids in HA and PB2 critical for the transmission of H5N1 avian influenza viruses in a mammalian host. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ge, J., G. Deng, Z. Wen, G. Tian, Y. Wang, J. Shi, X. Wang, Y. Li, S. Hu, Y. Jiang, C. Yang, K. Yu, Z. Bu, and H. Chen. 2007. Newcastle disease virus-based live attenuated vaccine completely protects chickens and mice from lethal challenge of homologous and heterologous H5N1 avian influenza viruses. J. Virol. 81:150-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatta, M., P. Gao, P. Halfmann, and Y. Kawaoka. 2001. Molecular basis for high virulence of Hong Kong H5N1 influenza A viruses. Science 293:1840-1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiao, P., G. Tian, Y. Li, G. Deng, Y. Jiang, C. Liu, W. Liu, Z. Bu, Y. Kawaoka, and H. Chen. 2008. A single-amino-acid substitution in the NS1 protein changes the pathogenicity of H5N1 avian influenza viruses in mice. J. Virol. 82:1146-1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim, J. K., P. Seiler, H. L. Forrest, A. M. Khalenkov, J. Franks, M. Kumar, W. B. Karesh, M. Gilbert, R. Sodnomdarjaa, B. Douangngeun, E. A. Govorkova, and R. G. Webster. 2008. Pathogenicity and vaccine efficacy of different clades of Asian H5N1 avian influenza A viruses in domestic ducks. J. Virol. 82:11374-11382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, Y. J., Y. K. Choi, Y. J. Kim, M. S. Song, O. M. Jeong, E. K. Lee, W. J. Jeon, W. Jeong, S. J. Joh, K. S. Choi, M. Her, M. C. Kim, A. Kim, M. J. Kim, E. H. Lee, T. G. Oh, H. J. Moon, D. W. Yoo, J. H. Kim, M. H. Sung, H. Poo, J. H. Kwon, and C. J. Kim. 2008. Highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1) in domestic poultry and relationship with migratory birds, South Korea. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:487-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li, C., K. Yu, G. Tian, D. Yu, L. Liu, B. Jing, J. Ping, and H. Chen. 2005. Evolution of H9N2 influenza viruses from domestic poultry in Mainland China. Virology 340:70-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li, Z., H. Chen, P. Jiao, G. Deng, G. Tian, Y. Li, E. Hoffmann, R. G. Webster, Y. Matsuoka, and K. Yu. 2005. Molecular basis of replication of duck H5N1 influenza viruses in a mammalian mouse model. J. Virol. 79:12058-12064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li, Z., Y. Jiang, P. Jiao, A. Wang, F. Zhao, G. Tian, X. Wang, K. Yu, Z. Bu, and H. Chen. 2006. The NS1 gene contributes to the virulence of H5N1 avian influenza viruses. J. Virol. 80:11115-11123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu, H., X. Liu, J. Cheng, D. Peng, L. Jia, and Y. Huang. 2003. Phylogenetic analysis of the hemagglutinin genes of twenty-six avian influenza viruses of subtype H9N2 isolated from chickens in China during 1996-2001. Avian Dis. 47:116-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, J., H. Xiao, F. Lei, Q. Zhu, K. Qin, X. W. Zhang, X. L. Zhang, D. Zhao, G. Wang, Y. Feng, J. Ma, W. Liu, J. Wang, and G. F. Gao. 2005. Highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus infection in migratory birds. Science 309:1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maines, T. R., X. H. Lu, S. M. Erb, L. Edwards, J. Guarner, P. W. Greer, D. C. Nguyen, K. J. Szretter, L. M. Chen, P. Thawatsupha, M. Chittaganpitch, S. Waicharoen, D. T. Nguyen, T. Nguyen, H. H. Nguyen, J. H. Kim, L. T. Hoang, C. Kang, L. S. Phuong, W. Lim, S. Zaki, R. O. Donis, N. J. Cox, J. M. Katz, and T. M. Tumpey. 2005. Avian influenza (H5N1) viruses isolated from humans in Asia in 2004 exhibit increased virulence in mammals. J. Virol. 79:11788-11800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen, T., C. T. Davis, W. Stembridge, B. Shu, A. Balish, K. Inui, H. T. Do, H. T. Ngo, X. F. Wan, M. McCarron, S. E. Lindstrom, N. J. Cox, C. V. Nguyen, A. I. Klimov, and R. O. Donis. 2009. Characterization of a highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus sublineage in poultry seized at ports of entry into Vietnam. Virology 387:250-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reed, L., and H. Muench. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. (Lond.) 27:493-497. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seo, S. H., E. Hoffmann, and R. G. Webster. 2002. Lethal H5N1 influenza viruses escape host anti-viral cytokine responses. Nat. Med. 8:950-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siengsanan, J., K. Chaichoune, R. Phonaknguen, L. Sariya, P. Prompiram, W. Kocharin, S. Tangsudjai, S. Suwanpukdee, W. Wiriyarat, R. Pattanarangsan, I. Robertson, S. D. Blacksell, and P. Ratanakorn. 2009. Comparison of outbreaks of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza in wild birds and poultry in Thailand. J. Wildl. Dis. 45:740-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith, G. J., X. H. Fan, J. Wang, K. S. Li, K. Qin, J. X. Zhang, D. Vijaykrishna, C. L. Cheung, K. Huang, J. M. Rayner, J. S. Peiris, H. Chen, R. G. Webster, and Y. Guan. 2006. Emergence and predominance of an H5N1 influenza variant in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:16936-16941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Songserm, T., R. Jam-on, N. Sae-Heng, N. Meemak, D. J. Hulse-Post, K. M. Sturm-Ramirez, and R. G. Webster. 2006. Domestic ducks and H5N1 influenza epidemic, Thailand. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:575-581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steel, J., A. C. Lowen, S. Mubareka, and P. Palese. 2009. Transmission of influenza virus in a mammalian host is increased by PB2 amino acids 627K or 627E/701N. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sturm-Ramirez, K. M., T. Ellis, B. Bousfield, L. Bissett, K. Dyrting, J. E. Rehg, L. Poon, Y. Guan, M. Peiris, and R. G. Webster. 2004. Reemerging H5N1 influenza viruses in Hong Kong in 2002 are highly pathogenic to ducks. J. Virol. 78:4892-4901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Subbarao, E. K., W. London, and B. R. Murphy. 1993. A single amino acid in the PB2 gene of influenza A virus is a determinant of host range. J. Virol. 67:1761-1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tian, G., S. Zhang, Y. Li, Z. Bu, P. Liu, J. Zhou, C. Li, J. Shi, K. Yu, and H. Chen. 2005. Protective efficacy in chickens, geese and ducks of an H5N1-inactivated vaccine developed by reverse genetics. Virology 341:153-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weber, S., T. Harder, E. Starick, M. Beer, O. Werner, B. Hoffmann, T. C. Mettenleiter, and E. Mundt. 2007. Molecular analysis of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus of subtype H5N1 isolated from wild birds and mammals in northern Germany. J. Gen. Virol. 88:554-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.WHO/OIE/FAO H5N1 Evolution Working Group. 2008. Toward a unified nomenclature system for highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu, J., H. H. Fang, J. T. Chen, J. C. Zhou, Z. J. Feng, C. G. Li, Y. Z. Qiu, Y. Liu, M. Lu, L. Y. Liu, S. S. Dong, Q. Gao, X. M. Zhang, N. Wang, W. D. Yin, and X. P. Dong. 2009. Immunogenicity, safety, and cross-reactivity of an inactivated, adjuvanted, prototype pandemic influenza (H5N1) vaccine: a phase II, double-blind, randomized trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:1087-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu, H., Z. Gao, Z. Feng, Y. Shu, N. Xiang, L. Zhou, Y. Huai, L. Feng, Z. Peng, Z. Li, C. Xu, J. Li, C. Hu, Q. Li, X. Xu, X. Liu, Z. Liu, L. Xu, Y. Chen, H. Luo, L. Wei, X. Zhang, J. Xin, J. Guo, Q. Wang, Z. Yuan, K. Zhang, W. Zhang, J. Yang, X. Zhong, S. Xia, L. Li, J. Cheng, E. Ma, P. He, S. S. Lee, Y. Wang, T. M. Uyeki, and W. Yang. 2008. Clinical characteristics of 26 human cases of highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) virus infection in China. PLoS One 3:e2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu, H., Y. Shu, S. Hu, H. Zhang, Z. Gao, H. Chen, J. Dong, C. Xu, Y. Zhang, N. Xiang, M. Wang, Y. Guo, N. Cox, W. Lim, D. Li, Y. Wang, and W. Yang. 2006. The first confirmed human case of avian influenza A (H5N1) in Mainland China. Lancet 367:84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang, P., Y. Tang, X. Liu, W. Liu, X. Zhang, H. Liu, D. Peng, S. Gao, Y. Wu, L. Zhang, and S. Lu. 2009. A novel genotype H9N2 influenza virus possessing human H5N1 internal genomes has been circulating in poultry in eastern China since 1998. J. Virol. 83:8428-8438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou, J., W. Sun, J. Wang, J. Guo, W. Yin, N. Wu, L. Li, Y. Yan, M. Liao, Y. Huang, K. Luo, X. Jiang, and H. Chen. 2009. Characterization of the H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus derived from wild pikas in China. J. Virol. 83:8957-8964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu, Q., H. Yang, W. Chen, W. Cao, G. Zhong, P. Jiao, G. Deng, K. Yu, C. Yang, Z. Bu, Y. Kawaoka, and H. Chen. 2008. A naturally occurring deletion in its NS gene contributes to the attenuation of an H5N1 swine influenza virus in chickens. J. Virol. 82:220-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.