Abstract

Acetonitrile hydratase (ANHase) of Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 is a cobalt-containing enzyme with no significant sequence identity with characterized nitrile hydratases. The ANHase structural genes anhA and anhB are separated by anhE, predicted to encode an 11.1-kDa polypeptide. An anhE deletion mutant did not grow on acetonitrile but grew on acetamide, the ANHase reaction product. Growth on acetonitrile was restored by providing anhE in trans. AnhA could be used to assemble ANHase in vitro, provided the growth medium was supplemented with 50 μM CoCl2. Ten- to 100-fold less CoCl2 sufficed when anhE was co-expressed with anhA. Moreover, AnhA contained more cobalt when produced in cells containing AnhE. Chromatographic analyses revealed that AnhE existed as a monomer-dimer equilibrium (100 mm phosphate, pH 7.0, 25 °C). Divalent metal ions including Co2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, and Ni2+ stabilized the dimer. Isothermal titration calorimetry studies demonstrated that AnhE binds two half-equivalents of Co2+ with Kd of 0.12 ± 0.06 nm and 110 ± 35 nm, respectively. By contrast, AnhE bound only one half-equivalent of Zn2+ (Kd = 11 ± 2 nm) and Ni2+ (Kd = 49 ± 17 nm) and did not detectably bind Cu2+. Substitution of the sole histidine residue did not affect Co2+ binding. Holo-AnhE had a weak absorption band at 490 nm (ϵ = 9.7 ± 0.1 m−1 cm−1), consistent with hexacoordinate cobalt. The data support a model in which AnhE acts as a dimeric metallochaperone to deliver cobalt to ANHase. This study provides insight into the maturation of NHases and metallochaperone function.

Keywords: Enzyme Catalysis, Metalloenzymes, Metalloproteins, Metals, Protein Metal Ion Interaction, Nitrile Hydratase

Introduction

Metals are essential to many biological processes, occurring in close to a third of structurally characterized proteins (1) where they mediate a variety of roles, including electron transfer, oxygen transport, and gene regulation. Despite their essential nature, metals are highly toxic. To balance these two characteristics, nature has developed metal-trafficking systems to capture trace metals in their free forms and to maintain metal homeostasis, including extremely low intracellular concentrations of free metals (2). The trafficking of metal ions is mediated by various accessory proteins, including metallochaperones. The latter have high affinity for specific metal ions, delivering them from other metal-trafficking or storage proteins to cognate apoenzymes to yield mature metalloenzymes (3).

Nitrile hydratases (NHases)3 are αβ-heterodimeric metalloproteins that catalyze the transformation of nitriles to amides. All NHases characterized to date contain either catalytically essential mononuclear Fe3+ (Fe-NHase) or Co3+ (Co-NHase) (4, 5). Both types of NHases utilize “activator proteins” for their maturation depending on the identity of their metal ion. P47K of Rhodococcus sp. N-771 represents a class of activator proteins involved in the functional expression of Fe-NHases (6). P47K interacts directly with the NHase and contains a conserved cysteine-rich motif, CXCC, which potentially plays a key role in iron binding. However, no direct evidence of the interaction with iron has been reported. Similarly, P14K plays a role in the maturation of Co-NHase of Rhodococcus rhodochrous J1 (7). A complex comprising two P14K (NhlE), the α-subunit of NHase (NhlA) and one cobalt ion, was isolated. P14K was demonstrated to mediate cobalt insertion and oxidation of the NHase cysteine residues (7), processes that are essential for NHase activity (8). At some point during this maturation, Co2+ is oxidized to Co3+ (7). Nevertheless, it is yet to be established whether P14K binds cobalt. Overall, activator proteins have been shown to be essential for the maturation of both Fe- and Co-NHases. However, direct association of these activator proteins with metals has not been reported, and thus their roles as metallochaperones have not been demonstrated.

Acetonitrile hydratase (ANHase) from Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 catalyzes the hydration of small aliphatic nitriles (9). Although ANHase is similar to other NHases in that it is an αβ-heterodimeric metalloenzyme, ANHase shares no significant amino acid sequence similarity with any protein in the databases, and the two subunits are much larger than those of characterized NHases. Second, ANHase contains an unusual complement of metal ions: one cobalt, two copper, and one zinc. Although the roles of these ions remain unclear, several findings suggest cobalt to be catalytically essential. First, the acetonitrile gene cluster includes anhT (Fig. 1A), whose product shares up to 75% amino acid sequence identity to the cobalt transporters associated with all Co-NHases such as that of R. rhodochrous J1 (10). Second, the electronic absorption spectrum of ANHase is typical of Co-NHases (11–13), with an absorption maximum at 414 nm and a shoulder at ∼350 nm, likely due to S → Co3+ charge transfer bands. Finally, the lack of cobalt in the growth media, but neither copper nor zinc, yielded inactive ANHase.4

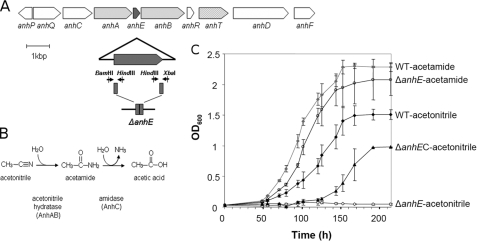

FIGURE 1.

The acetonitrile catabolic pathway in R. jostii RHA1. A, the anh gene cluster located on pRHL2. The anhE gene is black. Genes encoding the ANHase subunits (anhA and anhB) are shaded in dark gray, and a probable cobalt transporter (anhT) is shaded light gray. The portion of the anhE gene that was deleted is indicated below the cluster. Upstream and downstream fragments of anhE are shown in dark gray and arrows with restriction enzyme sites represent primers used to construct a deletion mutant. B, the deduced acetonitrile catabolic pathway. C, the growth of wild type RHA1 (WT), the anhE deletion mutant (ΔanhE), and the complemented mutant on acetonitrile and acetamide (ΔanhEC).

Herein, we report the characterization of AnhE, an 11.1-kDa protein whose gene is located between the ANHase structural genes anhA and anhB (Fig. 1A). The physiological role of the protein was evaluated through its in-frame deletion. A procedure for in vitro assembly was developed to investigate the role of AnhE in cobalt binding by ANHase. Finally, AnhE was heterologously produced, purified, and characterized with respect to its metal-binding properties. The findings are discussed with respect to the roles of metallochaperones in the maturation of metalloenzymes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Culture Condition

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in supplemental Table S1. Escherichia coli strains were grown in lysogeny broth (LB) at 37 °C, 200 rpm. E. coli DH5α was used to propagate DNA. AnhA, AnhB, and AnhE were produced alone and in various combinations using E. coli BL21 (DE3) grown in LB supplemented with 20 μg ml−1 of kanamycin. Expression of the anh genes was induced in cells that had attained an A600 of 0.5 by adding isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside to a final concentration of 0.5 mm. Cells were incubated for a further 16 h at 20 °C, harvested by centrifugation, and then frozen at −80 °C until further use. Rhodococcal strains were transformed as described previously (14) and were grown on W minimal medium supplemented with 0.1 m acetonitrile or acetamide as described previously (9).

Gene Deletion, Complementation, and Cloning

The anhE gene was deleted in-frame using a sacB counter-selection system (15). Briefly, the flanking regions of anhE were amplified using oligonucleotides containing BamHI, HindIII, and XbaI sites (supplemental Table S2), and the PCR products were cloned into pK18mobsacB (16). The resultant mutagenic plasmid pKΔanhE was electroporated into E. coli DH5α for construct verification and then introduced into E. coli S17-1 by chemical transformation, and finally mobilized into RHA1 by conjugation. The resultant kanamycin resistant (Kmr) Rhodococcus transconjugants were tested for sucrose sensitivity (Sucs). The Kmr Sucs colonies were selected and incubated to allow the second crossover. Resulting Kms Sucr colonies were selected and verified for deletion of anhE by colony PCR using two sets of primers, anhEupF/anhEdownR and anhEIntF/anhEIntR (supplemental Table S2). The resulting strain was named RHA023.

To complement the ΔanhE mutant, anhE was cloned into pTip-QC2, a Rhodococcus-E. coli expression vector (17). The anhE gene was amplified from fosmid RF00111A03 selected from the RHA1 fosmid library (18). A 300-bp amplicon containing anhE was amplified using an Expand high fidelity PCR system (Roche Applied Science) and the oligonucleotides indicated in supplemental Table S2. The resulting amplicon was cloned into pTip-QC2 using the NdeI and HindIII sites, yielding pTipAnhE.

To heterologously produce AnhE in E. coli, the above-described amplicon also was cloned in pET-41b to yield pETAnhE. For the ANHase activation assays, anhA, anhAE, and anhB were amplified using the primers indicated in supplemental Table S2 and were cloned into pET41-b, yielding pETAnhA, pETAnhAE, and pETAnhB, respectively. The respective nucleotide sequences of the cloned amplicons were verified.

Protein Purification

Cell pellets were resuspended in 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 4 °C containing 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The cells were disrupted by passing the suspension through an Avestin Emulsiflex-05 homogenizer operated at 10,000 psi. The cell suspension was centrifuged (36,000 × g for 40 min at 4 °C), and the resulting supernatant was passed through a 0.45-μm filter immediately prior to chromatography. Purified proteins were concentrated to ∼20 mg ml−1, flash frozen as beads in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

To purify AnhA, filtered extracts were loaded onto nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin and washed with 10 column volumes of 20 mm HEPES, pH 8.0. The bound proteins were eluted using 2 column volumes of 20 mm HEPES, pH 8.0, 250 mm imidazole, concentrated by ultrafiltration and applied to a 2 × 9 cm column of Source Q anion-exchange resin (GE Healthcare), which had been equilibrated with 20 mm HEPES, pH 8.0. The proteins were eluted using a 140-ml linear gradient of 0 to 0.7 m NaCl in 20 mm HEPES, pH 8.0.

To purify AnhB, the filtered cellular extract was applied to a 2 × 9 cm column of Source Q resin equilibrated with 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5. The proteins were eluted using a 60-ml linear gradient of 0 to 0.3 m NaCl in 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5. Fractions containing AnhB were pooled, concentrated to 4 ml by ultrafiltration and applied to a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 column equilibrated with 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl.

In vitro-assembled ANHase was purified by passing an incubated mixture of AnhA and AnhB through a 0.45-μm filter and applying this to a 0.5 × 5 cm column of Source Q anion-exchange resin equilibrated with 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5. The proteins were eluted at 1 ml min−1 using a 10-column-volume linear gradient of 0.2 to 0.5 m NaCl in 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5. Activity-containing fractions were pooled, concentrated to 4.0 ml and applied to a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 column operated at 3 ml min−1 and equilibrated with 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5 containing 50 mm NaCl. Activity-containing fractions were pooled, dialyzed against 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, and concentrated to 21 mg ml−1.

To purify AnhE, the filtered cellular extract was applied to a 2 × 9 cm column of Source Q resin equilibrated with 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.5. The proteins were eluted using a 70-ml linear gradient of 0 to 0.2 m NaCl in 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.5. Fractions containing AnhE were identified by denaturing gel analysis, pooled, and concentrated to 4 ml by ultrafiltration. The sample was applied to a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl. Purified AnhE was dialyzed for 16 h at 4 °C against a 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, buffer containing 5 mm EDTA followed by further dialysis with 20 mm HEPES buffer to remove EDTA.

Protein Analysis

The concentration of purified AnhE was determined using the Edelhoch method, with an extinction coefficient of 16,960 m−1 cm−1 at 280 nm, as estimated from the deduced amino acid sequence of protein and ProtParam software (on the ExPASy Proteomics Server) (19). Concentrations of AnhA and AnhB were determined using a Micro BCA protein assay (Pierce). Tricine-SDS-PAGE (20) was performed using separating gels containing 15% acrylamide. Gels were stained using Coomassie Brilliant Blue. The molecular mass of AnhE was determined by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry using an Applied Biosystems VOYAGER-DE STR work station.

Metal Analysis

Solutions of AnhA were dialyzed extensively against 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, dried in a SpeedVac concentrator (model SC110A, Thermo Savant, Milford, MA), and decomposed by heating with nitric acid. Controls consisted of the same volume of buffer. The metal content was analyzed using inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission mass spectrometer (ICP-MS) at Exova (Santa Fe Springs, Ca).

In Vitro Assembly of ANHase

ANHase was activated using three different methods. In the first method, 400 μg of AnhA-containing cell extract of E. coli grown in the presence of various concentrations of CoCl2 was incubated with 600 μg of purified AnhB in a total volume of 100 μl for 16 h at 4 °C. In the second method, 300 μg AnhA was used instead of cell extract. In the third method, 5 mg AnhA (purified from E. coli BL21 carrying pET41AnhAE, grown on LB media supplemented with 5 μm CoCl2), and 10 mg AnhB were incubated for 16 h at 4 °C. ANHase was purified from this mixture as described above under “Protein Purification.” ANHase activity was assayed discontinuously by quantifying ammonia release using a phenol-hypochlorite colorimetric assay adapted to 96-well plates (9).

Molecular Weight Determination of AnhE

The size of native AnhE was estimated using a Tricorn Superdex 75 (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, and operated at 0.4 ml min−1. In determining the size of AnhE-metal complexes, 0.1 mm AnhE was incubated with 0.1 m CoCl2, ZnCl2, NiCl2, or CuCl2 for 1 min at 25 °C immediately prior to loading the sample on the column. The column was calibrated using a low molecular mass standard comprising lysozyme (15,000), chymo-trypsinogen (25,000), carbonic anhydrase (32,000), β-lactoglobulin (36,000), and bovine serum albumin (68,000). The calibration curve was constructed by plotting Kav versus log Mr, where Kav = (Ve − V0)/(Vt − V0); Ve is the measured elution volume of each standard, V0 is the void volume of the column determined by Ve of blue dextran, and Vt is the total column volume as specified by the manufacturer.

Electronic Absorption Spectroscopy

Spectra were recorded using a Cary 4000 UV-visible spectrophotometer (Varian). Samples contained 500 μm AnhE in 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 25 °C, and various concentrations of CoCl2.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

Working solutions of 0.5–1.0 mm metal ion were prepared by diluting 100 mm stock solutions (CoCl2, ZnCl2, NiCl2, and CuCl2) in 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5. Titrations were performed at 25 °C using an iTC200 system (MicroCal, Northampton, MA). Experiments were conducted by injecting 0.5–1.0 μl of metal ion solution into 200 μl of 50 μm AnhE in 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5. To allow the system to reach the equilibrium, injections were spaced by 120 s. Titrations were repeated three to five times, and controls were conducted by (a) titrating metal ion solutions into the buffer alone and (b) titrating buffer into solutions of AnhE. Integrated heat release from each metal injection was fit using the Microcal Origin software (version 7.0) using a nonlinear least squares algorithm.

RESULTS

Growth Phenotypes of RHA1 and Mutant

The anhE gene (Locus ID RHA1_ro10171, accession number YP_708522) occurs between the two structural genes of ANHase and is predicted to encode an 11.1-kDa protein. To investigate the role of AnhE in the catabolism of nitriles by RHA1, anhE was subject to in-frame deletion and the growth phenotype of the resultant mutant, RHA023, was investigated. Unlike wild-type RHA1, RHA023 was unable to utilize acetonitrile as a growth substrate. In contrast, the mutant strain grew on acetamide at the same rate as the parent strain and to the same growth yield (Fig. 1C). Complementation of ΔanhE in trans restored growth on acetonitrile. Because the in-frame deletion of anhE affected growth on acetonitrile but not on acetamide, the hydration product of acetonitrile (Fig. 1B), these results strongly indicated that AnhE plays some role in the transformation of acetonitrile. As AnhE was not detected in preparations of purified ANHase, we hypothesized that the protein is involved in the maturation of ANHase. Attempts to complement the mutation by supplementing the growth medium with 5 or 50 μm CoCl2 were unsuccessful as this prevented growth of the mutant and wild type strains on minimal media.

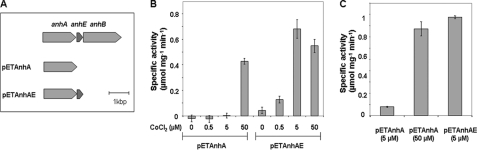

Assembly of ANHase in Vitro

AnhA, the α-subunit of ANHase, contains the sequence CLLGCAC, which is reminiscent of the CTSLCSC sequence of Co-NHases that binds the catalytically essential cobalt ion. To investigate the role of AnhE in ANHase maturation, anhA was expressed in E. coli either alone or with anhE (Fig. 2A). The strains were grown in LB supplemented with different amounts of CoCl2. Extracts of these cells were then incubated with purified AnhB, and ANHase activity was measured. As shown in Fig. 2B, activation of ANHase required the α- and β-subunits. Moreover, activity was obtained only when AnhA-containing extracts were prepared from cells grown in the presence of supplemental CoCl2. When AnhA was produced in cells without AnhE, 50 μm CoCl2 was required in the growth medium of AnhA-containing cells to observe ANHase activity. By contrast, when AnhA was co-produced in cells with AnhE, 0.5 to 5 μm of CoCl2 was sufficient.

FIGURE 2.

The assembly of ANHase in vitro. A, the portion of the anh gene cluster used to construct pETAnhA and pETAnhAE. B, the specific activity of ANHase reconstituted using cell extracts containing AnhA or AnhAE. Cells were grown in media supplemented with the indicated concentrations of CoCl2. C, the specific activity of ANHase reconstituted using purified AnhA. AnhA was purified from cells grown in media supplemented with the indicated concentrations of CoCl2. In the assembly experiments, purified AnhB was incubated with either cell extracts or purified AnhA. The concentration of CoCl2 supplemented in the growth media is indicated in B and C. Error bar represents S.E.

To further investigate the role of AnhE in the biosynthesis of ANHase, AnhA was purified from the various cell extracts, and its cobalt content was analyzed using ICP-MS. Samples of AnhA also were incubated with purified AnhB, and ANHase activity was determined using the colorimetric assay. When purified from cells containing no AnhE and grown in LB supplemented with 5 μm CoCl2, AnhA contained 0.06 ± 0.02 equivalents of cobalt (Fig. 2B), and the specific activity of the incubation mixture was 0.08 ± 0.01 mg ml−1 (Fig. 2C). When the same strain lacking AnhE was grown in LB supplemented with 50 μm CoCl2, the purified AnhA contained 0.49 ± 0.02 equivalents of cobalt, and the specific activity of the assembly mixture was 0.86 ± 0.07 mg ml−1. Finally, the cobalt content of purified AnhA was highest (0.56 ± 0.04 mol/mol) when the protein was purified from cells containing AnhE, even when the latter were grown in the presence of less CoCl2 (5 μm). Similarly, this preparation of AnhA yielded unpurified ANHase of the highest specific activity: 0.97 ± 0.07 mg ml−1. Attempts to assemble ANHase in vitro by incubating apo-AnhA, AnhE, AnhB, and CoCl2, to date, have yielded no detectable ANHase activity.

To better characterize the ANHase assembled in vitro, the activity was purified from the incubation mixture. In this experiment, 5 mg of AnhA (purified from AnhE-containing cells) was incubated with 10 mg AnhB at 4 °C for 16 h and further purified using anion exchange and gel filtration chromatography. The specific activity of purified, in vitro-assembled ANHase was 2.1 ± 0.1 units mg−1 (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 25 °C). This compares favorably with the wild-type enzyme (9) under these conditions: 2.3 ± 0.1 units mg−1. Overall, these results indicate that AnhE assists in delivering cobalt to AnhA in the maturation of ANHase.

Purification of AnhE

To further characterize the function of AnhE, the protein was produced and purified heterologously. The anhE gene was cloned downstream of the T7 promoter in pET-41b. Purification of AnhE using anion exchange and gel-filtration chromatography from cell extracts of E. coli BL21 containing pETAnhE yielded >53 mg of protein per liter of cell culture. SDS-PAGE analysis indicated that purified AnhE was apparently homogeneous. The molecular mass of AnhE, 11,071.13 Da, determined by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry was within 0.2% of the predicted value of 11,093.51 Da. As outlined below, the behavior of AnhE was dependent strongly on the presence of divalent metal ions. For this reason, AnhE preparations were dialyzed extensively against 5 mm EDTA and then EDTA-free buffer prior to experiments.

Metal-dependent Dimerization

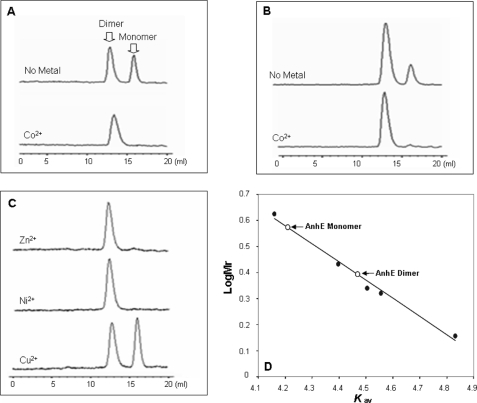

The oligomeric state of AnhE was investigated using gel-filtration chromatography. As shown in Fig. 3, AnhE existed as an equilibrium between two forms (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5) with apparent molecular masses of 16,200 ± 1,100 and 29,000 ± 2,000, respectively. These were taken to represent monomeric and dimeric forms of AnhE, respectively. Integration of the peak areas indicated that the equilibrium was ∼2:3 at 0.1 mm AnhE and shifted to ∼1:4 at 0.5 mm AnhE. Addition of 5 mm EDTA in the equilibration buffer did not prevent the dimerization of AnhE. Incubation of 0.1 mm AnhE with 0.1 mm CoCl2, ZnCl2, or NiCl2 shifted the equilibrium to essentially 100% of the dimeric form, consistent with metal ion-dependent dimerization of AnhE (Fig. 3C). By contrast, incubation of AnhE with 0.1 mm CuCl2 had no detectable effect on the dimerization property of AnhE. Higher order complexes were not detected in any of these experiments.

FIGURE 3.

The metal-dependent dimerization of AnhE. Protein samples were applied to a Superdex 75 10/300 GL column pre-equilibrated with 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl. Elution profiles were as follows: 0.1 mm AnhE before and after incubation with an equimolar amount of CoCl2 (A); 0.5 mm AnhE before and after incubation with an equimolar amount of CoCl2 (B); and 0.1 mm AnhE in the presence of 0.1 mm ZnCl2, NiCl2 andCuCl2 (C). D, standard curve for the molecular mass determination was established using lysozyme (15,000), chymotrypsinogen (25,000), carbonic anhydrase (32,000), β-lactoglobulin (36,000), and bovine serum albumin (68,000). The calculated sizes of the two indicated AnhE species were 16,200 and 29,000 and were taken to represent monomer and dimer, respectively.

Electronic Absorption Spectroscopy of AnhE

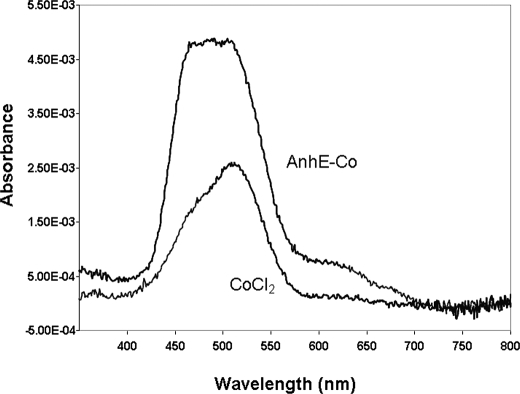

The d → d transitions of Co2+ give rise to weak bands between 450 and 700 nm in the electronic absorption spectrum and can be used to investigate the coordination geometry of the bound metal ion in proteins (21). The addition of 500 μm AnhE to a solution of 500 μm CoCl2 resulted in a blue-shifted, more intense absorption band of the latter (Fig. 4). This is consistent with a change in the coordination sphere of the cobalt ion and thus its binding to AnhE. The molar extinction coefficient of the AnhE-Co2+ complex at 490 nm, calculated on the basis of the cobalt concentration, was ϵ490 = 9.7 ± 0.1 m−1cm−1. The spectrum of the AnhE-Co2+ complex prepared using 500 μm AnhE and 250 μm CoCl2 was very similar, but half as intense (results not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Electronic absorption spectrum of cobalt-bound AnhE. The spectra of 500 μm CoCl2 and the difference spectrum for AnhE titrated with 1 eq of CoCl2 are shown. The difference spectrum was generated by subtracting the spectrum of apo-AnhE (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, at 25 °C).

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

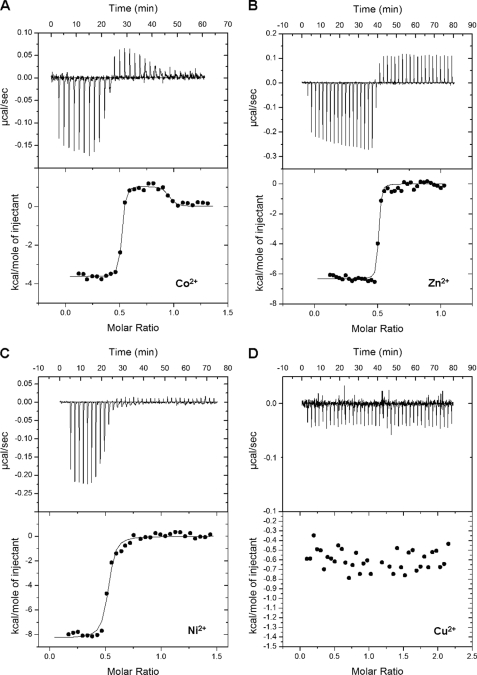

Electronic absorption spectra and gel-filtration chromatography studies indicated that AnhE interacts directly with divalent metal ions. To characterize the binding of metal ions by AnhE, a series of ITC experiments was performed. Inspection of the thermogram in Fig. 5A reveals that titration of a 50 μm solution of AnhE with 0.5 μl aliquots of 0.5 mm CoCl2 (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 25 °C) resulted in exothermic reactions (Fig. 5A). As titration continued, a rapid transition to endothermic reactions was observed. These reactions were dependent on both the metal ion and the protein and strongly suggest that Co2+ is involved in two distinct binding events. Indeed, a two-site model better fit the integrated heat release from each Co2+ addition. In the best fit, each site possessed a stoichiometry of n = 0.5 and nanomolar dissociation constants differing by three orders of magnitude. Based on replicate titrations, these constants were Kd1 = 0.12 ± 0.06 nm and Kd2 = 110 ± 35 nm. Although the value for Kd1 is relatively low for the ITC200 system, the quality of the data (Fig. 5A) indicates that the value is accurate. Together with the gel filtration studies, these results suggest the existence of two distinct metal-binding sites in AnhE homodimer.

FIGURE 5.

ITC analyses of the binding of Co2+ (A), Zn2+ (B), (C) Ni2+, and Cu2+ (D) to AnhE. Experiments were performed using 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, at 25 °C. The upper panels indicate calorimetric titrations (0.5–1 μl) of each divalent metal into 50 μm AnhE. The lower panels display the integrated heats from the upper panel as a function of the metal ion:protein molar ratio.

Titration of AnhE with Zn2+ or Ni2+ also resulted in exothermic reactions (Fig. 5, B and C), similar to those observed during the initial titration of the protein with Co2+. Unlike Co2+ and Ni2+, when Zn2+ ion was titrated into buffer alone, a consistent endothermic reaction was observed, similar to that observed in the titration with AnhE after the exothermic reactions were completed. This pattern indicates that the endothermic reaction with Zn2+ was not due to the binding of the metal ion to AnhE. Titration of AnhE with neither Zn2+ nor Ni2+ at concentrations up to 2.5 mm yielded the second phase of endothermic events observed with Co2+. Accordingly, a one-site model fit the binding of Zn2+ and Ni2+ to AnhE with n = 0.5 and Kd = 11 ± 2 nm and 49 ± 17 nm, respectively. It is possible that these metal ions bound to a second site but that this binding was either too weak or was driven entirely by entropy. Finally, AnhE did not bind Cu2+ detectably at concentrations up to 2.5 mm.

The calculated thermodynamic parameters for the above-described binding events, based on three to five replicates, are summarized in Table 1. The binding of Zn2+ and Ni2+, as well as the initial binding of Co2+ were driven by both favorable enthalpy and entropy reflecting the strength of the protein-metal ion interaction (22, 23). Moreover, enthalpies of Ni2+ and Zn2+ binding were more favorable than for Co2+; the higher affinity of AnhE for the latter (ΔΔG = −2.7 kcal mol−1 and −3.6 kcal mol−1, respectively) was due to the more favorable entropy. By contrast, the second binding transition for Co2+ was driven by favorable entropy, which offset the positive enthalpy. This is consistent with increased conformational freedom, such as desolvation, accompanying the occupation of the second binding site.

TABLE 1.

Thermodynamic parameters for ITC experiments

0.5 mm divalent metal solution was titrated into 50 μm AnhE in 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5 at 25 °C.

| N | Ka | Kd | ΔH | ΔS | ΔGa | Ka/Ka | ΔΔGb | Nc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ×10−9m−1 | Nm | kcal mol−1 | cal mol−1K−1 | kcal mol−1 | Co | kcal mol−1 | |||

| First binding | |||||||||

| Co2+ | 0.48 ± 0.03 | 10 ± 5 | 0.12 ± 0.06 | −3.7 ± 0.2 | 32 ± 3 | −13.6 ± 0.9 | 1 | 5 | |

| Zn2+ | 0.478 ± 0.002 | 0.1 ± 0.02 | 11 ± 2 | −6.8 ± 0.2 | 13.7 ± 0.9 | −10.9 ± 0.1 | 0.01 | −2.7 | 3 |

| Ni2+ | 0.49 ± 0.06 | 0.22 ± 0.07 | 49 ± 17 | −7.9 ± 0.4 | 7 ± 2 | −10.0 ± 0.2 | 0.0022 | −3.6 | 5 |

| Second binding | |||||||||

| Co2+ | 0.42 ± 0.04 | 10 × 106 ± 4 × 106 | 110 ± 35 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 36 ± 2 | −9.0 ± 0.8 | 1 | 5 | |

a ΔG = RT ln Ka, T = 298 K.

b ΔΔG = RT ln (Ka/Ka (co)).

c n = number of observations.

The Role of His41 in Cobalt Binding

AnhE contains no cysteine residues and only a single histidine residue, His41. To investigate the role of this residue as a ligand, it was substituted with alanine, and the metal-binding properties of the resultant H41A variant were investigated. ITC data obtained using Co2+ fit a two-site model with Kd1 of 0.13 ± 0.08 nm and Kd2 = 140 ± 60 nm, and each site possessing a stoichiometry of n = 0.5. These results are remarkably similar to what was observed in wild type AnhE, indicating that His41 is not involved in metal ion binding.

DISCUSSION

The current study establishes that AnhE is required for the in vivo production of functional ANHase, a cobalt-dependent nitrile hydratase. In vitro assembly studies established that AnhE facilitates the binding of cobalt by the ANHase α-subunit. It was further demonstrated that AnhE binds a number of divalent metal ions with nanomolar affinity and that these ions promote the dimerization of this small protein. However, AnhE bound Co2+ with the highest affinity and bound twice as many equivalents of Co2+ as other tested metal ions. As discussed below, the requirement of AnhE for the production of active ANHase, its role in assisting cobalt binding by AnhA, the high affinity of AnhE for its physiologically relevant metal ion, and its metal ion-induced conformational changes are characteristic of metallochaperones. Overall, the data indicate that the physiological role of AnhE is to deliver cobalt ion to ANHase.

The high affinity of AnhE for Co2+ is consistent with the high affinity of other metallochaperones for their physiologically relevant metal ions. More specifically, the value for AnhE (Kd1 = 0.12 ± 0.06 nm) is intermediate between those of UreE (Kd = 1.6 nm (24)) and HypB, an Ni2+-specific metallochaperone for [NiFe]-hydrogenase, (Kd = 0.13 to 0.44 pm (25)). Similarly, IscA, a metallochaperone involved in the assembly of iron-sulfur clusters, binds to Fe2+ with subpicomolar affinity (26). The much higher affinity of AnhE for Co2+ versus Zn2+ (Kd = 11 nm) is remarkable given that these two metal ions often utilize similar donor ligands and can accommodate the same coordination geometry (27, 28). Nevertheless, the higher affinity of AnhE for Co2+ versus Ni2+ or Zn2+ is consistent with the higher affinity of UreE for Ni2+ versus Zn2+ (24).

The metal ion-binding sites in metallochaperones are often quite unusual as they must not only tightly bind the metal ion so as to avoid cytotoxic effects but also release it to the target protein. The presented data indicate that the Co2+-binding sites of AnhE are hexacoordinate and that the lone histidinyl residue in the protein does not contribute directly to them. More particularly, the low extinction coefficient of AnhE-Co2+ (ϵ490 = 9.7 m−1 cm−1) is within the range of that observed for six-coordinate sites. By contrast, four- and five-coordinate sites have extinction coefficients >50 and 300 m−1 cm−1, respectively (29). Whereas the current data establish that His is not a Co2+ ligand in AnhE, further study is required to identify the metal ligands of AnhE and to elucidate the metal ion specificity of the protein.

The Co2+-induced dimerization of AnhE is similar to metal ion-induced conformational changes in metallochaperones and other proteins. For example, the metal-binding sites of UreE, HypB and IscA occur at their respective subunit interfaces and appear to stabilize the functional oligomeric forms of these proteins (30–34). Similarly, the binding of Zn2+ to the zinc finger induces a conformational change from an extended β-sheet to the ββα hairpin structure required for recognition of target DNA sequences (35). Moreover, the binding of Ni2+ to NikR, a prokaryotic transcription factor, triggers a conformational change that results in the regulation of the expression of nickel-containing enzymes and transporters. Intriguingly, this rearrangement was not induced by Zn2+ binding (36). This specificity of the conformational change in NikR for Ni2+ is similar to the Co2+-specific changes in AnhE activity.

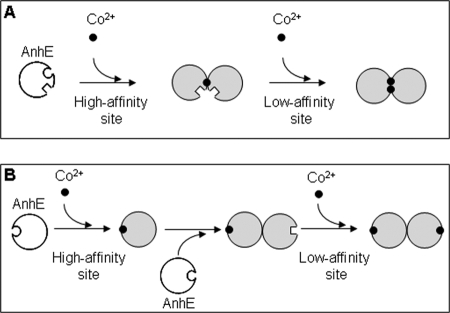

The current data suggest a model in which a functional homodimer of AnhE binds two equivalents of Co2+. Although the thermodynamic analyses clearly revealed that AnhE binds two half-equivalents of Co2+ with different affinities, specific metal-binding sites cannot be proposed. Nevertheless, the current data indicate that binding could involve one of two scenarios. In the first case (Fig. 6A), the ions bind at the AnhE dimer interface. In this case, there are two such sites for Co2+ and either one or two for Zn2+ or Ni2+ (with the second site being too weak to detect). In a second scenario (Fig. 6B), the binding site does not involve residues at the dimer interface but drives dimerization through conformational changes and, as a result, alters the affinity of the ion for the second molecule in the dimer. The first scenario is reminiscent of UreE, a Ni2+-specific metallochaperone involved in the maturation of urease. The UreE homodimer binds two nickel ions at nonidentical sites present at the dimer interface (37). These sites also accommodate Cu2+ and Co2+. However, a variety of spectroscopic methods indicate that the coordination environment is different for Ni2+, facilitating its selection for urease activation (37, 38). It is possible that Co2+ interacts with AnhE in a similar manner.

FIGURE 6.

Proposed mechanisms of the influence of Co2+ binding on the activity of AnhE. A, Co2+ binds to high and low affinity sites at the AnhE homodimer interface. B, Co2+ binds away from the dimer interface but drives dimerization through conformational changes. Circular and square surfaces represent high and low affinity sites, respectively. The implied equivalence of the two sites in the AnhE2(Co2+)2 species is unintended.

The lack of significant sequence identity between AnhE and two other potential Co2+-specific metallochaperones, P14K and CobW, limits comparison of their respective modes of action. Nevertheless, the model for AnhE action shares some similarities with that proposed for P14K in the self-subunit swapping model of Co-NHase maturation (39). These include the action of the chaperone as a dimer and the preferred binding of a single Co2+ by the dimer. For its part, CobW occurs in the aerobic biosynthesis of cobalamine pathway (40). In the latter, Co2+ is inserted into the corrin ring by cobaltochelatase, an enzyme consisting of three subunits: CobN, CobS, and CobT (41). CobW, whose gene is always located immediately upstream of cobN (40), is essential for cobalamin biosynthesis (42) and has been proposed to deliver cobalt to the chelatase complex. As in P14K, no direct evidence of cobalt binding to CobW has been reported. Interestingly, CobW shares 20–30% amino acid sequence identity with HypB and UreG, the GTP-utilizing, Ni2+-specific metallochaperones discussed above, as well as ∼30% identity and a possible metal-binding motif with P47K, the potential metallochaperone of Fe-NHase. Neither ATP/GTPase activity nor metal binding has been reported in either P47K or P14K.

Although this study establishes that AnhE binds Co2+ and facilitates its incorporation into AnhA, the oxidation state of the cobalt in ANHase is unclear. In other Co-NHases, the cobalt is trivalent. The hydrolysis of nitrile is mediated by the inert Co3+, whose ligand exchange rate is significantly increased in the presence of thiolate ligands (43). In addition, the Lewis acidity of the Co3+ is increased by the oxidation of cysteinyl ligands to sulfenic and sulfinic acids (44). Co-NHase has been reconstituted aerobically using either Co2+ or Co3+ (7). However, the exact mechanism of Co2+ oxidation remains uncertain. AnhA contains a Cys-rich motif that may bind cobalt. Moreover, mass spectrometry data indicate that one of these residues is a sulfinic acid.4 Thus, ANHase may utilize Co3+ in a similar mechanism as other Co-NHases. Nevertheless, ITC experiments performed using Co(NH3)6Cl3 indicated that AnhE does not bind Co3+ (data not shown).

We are currently investigating the structure and the metal-binding sites of AnhE as well as the mechanism of metal-transfer to apo-ANHase. Combined with the current study, these should provide further insights into the maturation of NHases as well as the metal specificity and mechanism of metallochaperones.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Kelvin Lau for assistance with the ITC analyses.

This work was supported by grants from Genome Canada and a Discovery grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada (to L. D. E.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and additional references.

S. Okamoto and L. D. Eltis, unpublished data.

- NHase

- nitrile hydratase

- ANHase

- acetonitrile hydratase

- Co-NHase

- co-nitrile hydratase; N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine

- MALDI-TOF

- matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight

- ICP-MS

- inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission mass spectrometer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gray H. B. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 3563–3568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rae T. D., Schmidt P. J., Pufahl R. A., Culotta V. C., O'Halloran T. V. (1999) Science 284, 805–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finney L. A., O'Halloran T. V. (2003) Science 300, 931–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee A., Sharma R., Banerjee U. C. (2002) Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 60, 33–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan B. A., Cummings J. G., Chase D. B., Turner I. M., Jr., Nelson M. J. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 10068–10077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu J., Zheng Y., Yamagishi H., Odaka M., Tsujimura M., Maeda M., Endo I. (2003) FEBS Lett. 553, 391–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou Z., Hashimoto Y., Kobayashi M. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 14930–14938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashimoto K., Suzuki H., Taniguchi K., Noguchi T., Yohda M., Odaka M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 36617–36623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okamoto S., Eltis L. D. (2007) Mol. Microbiol. 65, 828–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Komeda H., Kobayashi M., Shimizu S. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 36–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagasawa T., Takeuchi K., Yamada H. (1991) Eur. J. Biochem. 196, 581–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payne M. S., Wu S., Fallon R. D., Tudor G., Stieglitz B., Turner I. M., Jr., Nelson M. J. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 5447–5454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashimoto Y., Sasaki S., Herai S., Oinuma K., Shimizu S., Kobayashi M. (2002) J. Inorg. Biochem. 91, 70–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalscheuer R., Arenskötter M., Steinbüchel A. (1999) Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 52, 508–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Geize R., Hessels G. I., van Gerwen R., van der Meijden P., Dijkhuizen L. (2001) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 205, 197–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schäfer A., Tauch A., Jäger W., Kalinowski J., Thierbach G., Pühler A. (1994) Gene 145, 69–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakashima N., Tamura T. (2004) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 5557–5568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLeod M. P., Warren R. L., Hsiao W. W., Araki N., Myhre M., Fernandes C., Miyazawa D., Wong W., Lillquist A. L., Wang D., Dosanjh M., Hara H., Petrescu A., Morin R. D., Yang G., Stott J. M., Schein J. E., Shin H., Smailus D., Siddiqui A. S., Marra M. A., Jones S. J., Holt R., Brinkman F. S., Miyauchi K., Fukuda M., Davies J. E., Mohn W. W., Eltis L. D. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 15582–15587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edelhoch H. (1967) Biochemistry 6, 1948–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schägger H. (2006) Nat. Protoc. 1, 16–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adrait A., Jacquamet L., Le Pape L., Gonzalez de Peredo A., Aberdam D., Hazemann J. L., Latour J. M., Michaud-Soret I. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 6248–6260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcus Y. (1994) J. Solution Chem. 23, 831–848 [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiTusa C. A., Christensen T., McCall K. A., Fierke C. A., Toone E. J. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 5338–5344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grossoehme N. E., Mulrooney S. B., Hausinger R. P., Wilcox D. E. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 10506–10516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leach M. R., Sandal S., Sun H., Zamble D. B. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 12229–12238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding H., Harrison K., Lu J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30432–30437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folk J. E., Gladner J. A. (1960) J. Biol. Chem. 235, 60–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tu C. K., Silverman D. N. (1985) Biochemistry 24, 5881–5887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bertini I., Luchinat C., Scozzafava A. (1982) Structure and Bonding 48, 45–92 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gasper R., Scrima A., Wittinghofer A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 27492–27502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee M. H., Pankratz H. S., Wang S., Scott R. A., Finnegan M. G., Johnson M. K., Ippolito J. A., Christianson D. W., Hausinger R. P. (1993) Protein Sci. 2, 1042–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu C., Olson J. W., Maier R. J. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 2333–2337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bilder P. W., Ding H., Newcomer M. E. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 133–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cupp-Vickery J. R., Silberg J. J., Ta D. T., Vickery L. E. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 338, 127–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miura T., Satoh T., Takeuchi H. (1998) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1384, 171–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zambelli B., Danielli A., Romagnoli S., Neyroz P., Ciurli S., Scarlato V. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 383, 1129–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colpas G. J., Brayman T. G., Ming L. J., Hausinger R. P. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 4078–4088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colpas G. J., Brayman T. G., McCracken J., Pressler M. A., Babcock G. T., Ming L. J., Colangelo C. M., Scott R. A., Hausinger R. P. (1998) Journal of Bioinorganic Chemistry 3, 150–160 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou Z., Hashimoto Y., Shiraki K., Kobayashi M. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 14849–14854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodionov D. A., Vitreschak A. G., Mironov A. A., Gelfand M. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41148–41159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Debussche L., Couder M., Thibaut D., Cameron B., Crouzet J., Blanche F. (1992) J. Bacteriol. 174, 7445–7451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roth J. R., Lawrence J. G., Rubenfield M., Kieffer-Higgins S., Church G. M. (1993) J. Bacteriol. 175, 3303–3316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shearer J., Kung I. Y., Lovell S., Kaminsky W., Kovacs J. A. (2001) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 463–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kovacs J. A. (2004) Chem. Rev. 104, 825–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.