Abstract

HCT-8 colon cancer cells secreted heat shock protein 90α (HSP90α) and had increased invasiveness upon serum starvation. The concentrated conditioned medium of serum-starved HCT-8 cells was able to stimulate the migration and invasion of non-serum-starved cells, which could be prevented by treatment with an anti-HSP90α antibody. Recombinant HSP90α (rHSP90α) also enhanced HCT-8 cell migration and invasion, suggesting a stimulatory role of secreted HSP90α in cancer malignancy. HSP90α binding to CD91α and Neu was evidenced by the proximity ligation assay, and rHSP90α-induced HCT-8 cell invasion could be suppressed by the addition of anti-CD91α or anti-Neu antibodies. Via CD91α and Neu, rHSP90α selectively induced integrin αV expression, and knockdown of integrin αV efficiently blocked rHSP90α-induced HCT-8 cell invasion. rHSP90α induced the activities of ERK, PI3K/Akt, and NF-κB p65, but only NF-κB activation was involved in HSP90α-induced integrin αV expression. Additionally, we investigated the serum levels of HSP90α and the expression status of tumor integrin αV mRNA in colorectal cancer patients. Serum HSP90α levels of colorectal cancer patients were significantly higher than those of normal volunteers (p < 0.001). Patients with higher serum HSP90α levels significantly exhibited elevated levels of integrin αV mRNA in tumor tissues as compared with adjacent non-tumor tissues (p < 0.001). Furthermore, tumor integrin αV overexpression was significantly correlated with TNM (Tumor, Node, Metastasis) staging (p = 0.001).

Keywords: Cell Migration, Chaperone Chaperonin, Integrin, NF-kappa B, Protein Secretion, CD91/LRP, HSP90-alpha, integrin alpha-V, Invasion

Introduction

Heat shock protein 90α (HSP90α)2 is a molecular chaperone that aids in proper protein folding, maturation, and intracellular trafficking of numerous proteins (1). Thus far, more than 100 proteins have been identified that are regulated by HSP90α, including Akt, Neu/Her-2 (ErbB2), HIF-1α, Bcr-Abl, Raf-1, and mutated p53 (2). Many of these proteins are important mediators of signal transduction and cell cycle control and are also involved in the development and progression of cancer cells. Increasing evidence has suggested HSP90α as a novel therapeutic target. By inhibiting its chaperone activity, many HSP90α inhibitors cause the destabilization and eventual degradation of client proteins, and therefore, exhibit potent in vitro and in vivo anti-cancer activities (3). Among them, 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin is a first-in-class HSP90α inhibitor and is currently in phase II clinical trials. Nevertheless, most studies regarding HSP90α have focused on its function as a cytosolic chaperone; the secretion of HSP90α has been less well studied until recently.

HSP90α is not only expressed in the cytoplasm, but it is also localized on the cell surface (4–6). Through an interaction with the extracellular domain of Neu/Her-2, surface HSP90 is involved in heregulin-induced Neu/Her-2 activation and signaling, leading to cytoskeletal rearrangements and migration and invasion of breast cancer cells (7). Recent studies have shown that HSP90 could be secreted by keratinocytes, non-small cell lung cancer CL1–5 cells, and breast cancer MCF-7 cells (8–12). During skin wound healing, transforming growth factor-α induced keratinocytes to secrete HSP90α via an unconventional exosome pathway (9, 11). Secreted HSP90α promoted both epidermal and dermal cell migration through their surface receptor CD91/LRP-1 (11). In a human cancer study, an elevated level of secreted HSP90α was detected from highly invasive CL1–5 cells as compared with their less invasive parental cells (10). Additionally, secretion of HSP90α was significantly induced from MCF-7 cells after stimulation with a variety of growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, and stromal cell-derived factor-1 (12).

In our present study, human colon cancer HCT-8 cells secreted HSP90α and increased cell invasiveness after serum starvation. Via CD91/LRP-1 and Neu, HSP90α selectively induced integrin αV expression, and shRNA-mediated knockdown of integrin αV efficiently blocked HSP90α-induced HCT-8 cell invasion. HSP90α induced activation of ERK, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), and NF-κB p65 in HCT-8 cells, but only NF-κB activation was involved in HSP90α-induced integrin αV expression. In addition, we investigated the serum levels of HSP90α from 172 colorectal cancer (CRC) patients and the expression status of tumor integrin αV mRNA from 118 patients and analyzed their clinical relevance.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Reagents

HCT-8 cells were cultivated in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 20 mm l-glutamine. Cultures were maintained at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. Anti-HSP90α and anti-Neu antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Two anti-CD91α antibodies, obtained from BD Biosciences and AbD Serotec (Kidlington, Oxford, UK), were used in the experiments as indicated. Antibodies against integrin αV, Ser-536-phosphorylated NF-κB p65 (BD Biosciences), NF-κB p65 (Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, CA), Ser-473-phosphorylated Akt (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), Akt, ERK, phosphorylated ERK, JNK, phosphorylated JNK, p38, and phosphorylated p38 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used for immunoblot analyses. Human recombinant HSP90α (rHSP90α) was provided by StressGen (Ann Arbor, MI). Matrigel and Transwell inserts were purchased from BD Biosciences. Chemicals, including PD98059 (MAPK kinase/ERK kinase (MEK) inhibitor), SB202190 (p38 inhibitor), SP600125 (JNK inhibitor), and 6-amino-4-(4-phenoxyphenylethylamino) quinazoline (NF-κB activation inhibitor), were purchased from Calbiochem (EMD Biosciences). The PI3K inhibitor Ly294002 was obtained from Cell Signaling.

Clinical Specimens

Clinical samples were collected from CRC patients consecutively admitted to Chang Gung Memorial Hospital from August 2007 to February 2008. Serum samples were collected before surgery from 172 patients. The sera of 10 healthy volunteers were also included in the study for comparison. Tumor tissues were taken from surgical resections of 118 patients, and adjacent non-tumor tissues were obtained from the distal edge of each resection at least 10 cm away from the tumor. In the total collected 241 patients, 49 patients contributed both their serum specimens and their tissue specimens. Written informed consent from all patients was obtained in accordance with medical ethics required and approved by the Human Clinical Trial Committee at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. After surgery, the clinical stage of each patient was estimated from surgical and pathological reports using the TNM system. Patients who had received any chemo- and/or radio-therapeutic treatment before surgery were excluded from this study.

Flow Cytometric Analysis of Cell Surface HSP90α

Adherent HCT-8 cells were trypsinized and suspended in PBS plus 1% bovine serum albumin at a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml. After incubation at 4 °C for 1 h, the cell suspension was treated with 4 μg/ml anti-HSP90α antibody at 4 °C for another hour. After two washes with PBS, fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody (2 μg/ml) was added to the cell suspension and incubated in dark at 4 °C for 40 min. After two washes with PBS, the cells were suspended in PBS, and the fluorescence intensity was analyzed by FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Immunoblot Analysis

Whole cell lysates were prepared in cell lysis buffer consisting of 10 mm Na2HPO4, 1.8 mm KH2PO4, pH 7.4, 137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.3% SDS, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Protein concentrations of the cell lysates were determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad). Each sample (40 μg) was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was blocked in PBST (PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20) plus 5% nonfat milk for 60 min at room temperature. The membrane was incubated with primary antibody in PBST plus 5% nonfat milk overnight at 4 °C. The membrane was washed three times with PBST for 15 min each time at room temperature and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 60 min. Following three washes with PBST, immunoreactive bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences).

Serum Starvation and Conditioned Medium Collection

HCT-8 cells were seeded at a density of 1.5 × 106 cells in a 10-cm dish and incubated overnight. Cells were then washed twice with PBS, and 10 ml of fresh RPMI medium containing 0.5% FBS was added for serum starvation. After the indicated time periods, media were collected, centrifuged, and filtered through 0.45-μm filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The filtered media were used directly for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) experiments or concentrated by 10% trichloroacetic acid at 4 °C for at least 30 min for immunoblot analysis. For conditioned medium (CM) experiments, cells were washed twice with PBS after 5 days of serum starvation and incubated with 10 ml of fresh serum-free RPMI medium per dish for another 24 h. The medium was collected as CM for the cancer cell migration and invasion assays after being concentrated by an Amicon Ultracel-30k centrifugal filter (Millipore). The serum-free RPMI medium, which was incubated at 37 °C for the same period, was used as control medium.

ELISA

Aliquots of cell media were put into 96-well plates (100 μl/well), incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, and washed three times with PBS plus 0.05% Tween 20. PBS plus 5% bovine serum albumin were added to each well and incubated for another hour at 37 °C. Each well was washed once with PBS plus 0.05% Tween 20 and was then incubated with anti-HSP90α antibody (1 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 1 h. After three washes, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was added and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. After three washes with PBS plus 0.05% Tween 20, 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (0.3 mg/ml; Sigma) in 0.015% H2O2 were added to each well and incubated for 10 min in the dark at room temperature. The reactions were stopped by the addition of 0.5 m H2SO4. Optical density values were measured at 450 nm by an Infinite M200 microplate reader (TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland). Different amounts of rHSP90α diluted in 0.05 mg/ml bovine serum albumin were used as standards. The levels of HSP90α in clinical serum samples (diluted 20×) were detected in the same way, except that rHSP90α standards were prepared in 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin.

Cancer Cell Migration and Invasion Assays

HCT-8 cells were plated in 6-well plates and grown to confluence. The monolayer of cells was wounded with a white tip. After wounding, cells were washed twice with PBS and treated as indicated at 37 °C for 16 h. Pictures were taken of the cells that had migrated into the wounded area and quantified using the Image-Pro Plus version 5.0.2 software (MediaCybernetics Inc., Silver Spring, MD). There were two invasion assays performed in this study: Matrigel island and Transwell assays. In the Matrigel island invasion assay, Matrigel was 1:3 diluted with serum-free RPMI medium and solidified in a well of a 6-well plate at 37 °C for 30 min to form a Matrigel island. A hole was carefully made at the center of the Matrigel island in which HCT-8 cells, growing or serum-starved and mixed with Matrigel (1:3 diluted with serum-free RPMI medium), were seeded. RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS was then added around the island. Time-lapse photography was performed to monitor an 8-h process of HCT-8 cell invasion in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator using the CCM-330F system (Astec Co., Fukuoka, Japan) and analyzed by the Image-Pro Plus software. In the Transwell invasion assay, the Transwell inserts (8-μm pores) were first coated with Matrigel (1:5 diluted with RPMI medium) and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. HCT-8 cells, treated as indicated, were plated in the top chambers of the Transwell inserts. Cells were allowed to migrate for 24 h through the Matrigel toward RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS in the bottom chambers. The filters of Transwell inserts were then fixed and stained with Giemsa, pictures were taken of the invasive cells on the filters, and cells were counted by the Image-Pro Plus software.

Proximity Ligation Assay

HCT-8 cells were seeded on glass coverslips (2 × 105 cells/22 × 22-mm coverslip) and cultured overnight. Cells were washed twice with PBS and treated for 16 h with 10× control medium or 10× CM. Treated cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde and blocked with the blocking solution supplied in the Duolink in situ PLA kit (Olink Bioscience, Uppsala, Sweden). Cells were then incubated with 20 μg/ml primary antibody against CD91α (AbD Serotec) or Neu (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4 °C and washed three times with Tris-buffered saline plus 0.05% Tween 20 followed by incubation with 10 μg/ml anti-HSP90α antibody (Santa Cruz) for 1 h at room temperature. The subsequent procedure was the same as described in the manufacturer's instructions of the Duolink in situ PLA kit. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole for 2 min in the dark at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted with mounting solution overnight in the dark at room temperature; images were taken and analyzed using the TSC SP5 confocal microscope and LASAF software (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA of HCT-8 cells or tissues was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and reverse-transcribed at 37 °C with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland). The resultant cDNA was used as the template for PCR reactions. Real-time PCR reactions were performed on a RotorGene 3000 system (Corbett Research, Mortlake, Australia) using SYBR Green PCR master mix according to the manufacturer's protocol (Cambrex Co., East Rutherford, NJ). The sets of forward and reverse primers and the corresponding PCR annealing temperatures and the lengths of PCR products are as follows: integrin αM (5′-ACA GAG CTG CCT CTC GGT GGC CA-3′, 5′-TTC CCT TCT GCC GGA GAG GCT ACG C-3′, 52 °C and 490 bp); integrin αV (5′-ATA GGG TGA CTT GTG TTT TTA GG-3′, 5′-AAA GAC ATG ATT GCT AAG GTC C-3′, 52 °C and 227 bp); integrin α5 (5′-CCT CCC AAT TTC AGA CTC CC-3′, 5′-ACA AGG GTC CTT CAC AGT GC-3′, 52 °C and 205 bp); integrin β1 (5′-TCC TAT TTT AAC ATT ACC AA-3′, 5′-ACT GTG ACT ATG GAA ATT GC-3′, 52 °C and 462 bp); integrin β2 (5′-GAG AAA GAT TCT GCT CTG A-3′, 5′-AGC CTG TAA TTG AAG TTT TAT-3′, 52 °C and 529 bp); integrin β3 (5′-GGC CTG TTC TTC TAT GGG TT-3′, 5′-GTG GGA GTG TCT GTA CCC TG-3′, 52 °C and 220 bp); and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (5′-GAA GGT GAA GGT CGG AGT-3′, 5′-GAA GAT GGT GAT GGG ATT TC-3′, 52 °C and 220 bp). The PCR reaction mixtures were first denatured at 94 °C for 5 min. The reactions were then incubated at 94 °C for 1 min, annealed for 1 min, and incubated at 72 °C for 3 min for 30 cycles. Finally, the reactions were terminated at 72 °C for 7 min. Data were analyzed using the RotorGene software version 5.0 (Corbett Research). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase levels were used as internal controls for normalization.

Generation of Integrin αV Knockdown Cells

The lentiviral plasmid expressing a 21-mer shRNA directed against integrin αV mRNA was obtained from the National RNAi Core Facility (Taipei, Taiwan). HCT-8 cells were transfected with empty vector (pLKO.1 puro) or integrin αV shRNA-expressing plasmid (2 μg of DNA/105 cells for 48 h) using the Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The transfectants were selected against 2 μg/ml puromycin for 10 days, and cell clones were screened for integrin αV silencing by RT-PCR and immunoblot analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The cell line results were obtained from at least three independent experiments, and the data differences calculated using the Student's t test were considered significant if p < 0.05. Independent samples t test was adopted to analyze the serum HSP90α levels of patients, and Pearson chi-square analysis was used to evaluate the correlation of tumor integrin αV mRNA overexpression with the higher serum HSP90α levels and the TNM staging of CRC (SPSS 11.0 software; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Secretion of HSP90α from HCT-8 Cells after Serum Starvation

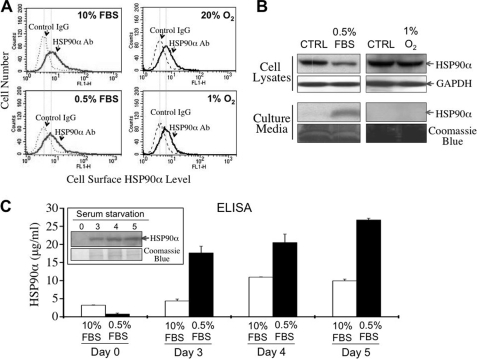

Our studies were designed to investigate whether cellular expression and location of HSP90α were affected by stresses such as hypoxia and nutrition deficiency. Flow cytometry data indicated that there was no significant difference in HSP90α expression on the cell surface of HCT-8 cells after serum starvation or hypoxia (Fig. 1A). However, there was a significant decrease of HSP90α levels in lysates after serum starvation but not hypoxia (Fig. 1B). The decrease in lysates was accompanied by a significant increase of HSP90α levels in culture media. A lactate dehydrogenase assay of media was also performed and revealed no significant difference in the media collected from normally cultured or serum-starved cells (supplemental Fig. 1), suggesting that the release of HSP90α into the culture medium resulted from cellular secretion, not from cell death. By ELISA, we further measured secreted amounts of HSP90α into culture media. Approximately 18 μg/ml HSP90α was detected in the 3-day serum starvation medium, which was increased to 26.74 ± 1.31 μg/ml after 5 days of serum starvation (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

HSP90α secretion induced by serum starvation. A, cell surface HSP90α levels of HCT-8 cells were not obviously changed by 24 h of hypoxia or 72 h of serum starvation. Ab, antibody. B, the level of HSP90α was decreased in the cell lysate but increased in the culture medium of HCT-8 cells after serum starvation but not hypoxia. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. C, measurement of the secreted amounts of HSP90α in culture media by ELISA. The data shown are the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. Approximately 18 and 27 μg/ml HSP90α was detected from the 3- and 5-day serum starvation media, respectively. In normally cultured cells, an increase of HSP90α (from 3 to 11 μg/ml) was detected from the 4-day culture medium. The amount of HSP90α was no more increased in the 5-day culture medium. The inset is a representative immunoblot result to confirm the immunoreactive specificity of the assays.

Secreted HSP90α as an Inducer of Cancer Cell Migration and Invasion

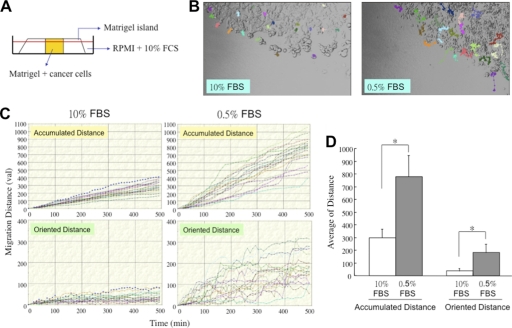

Because secretion of HSP90α was induced by serum starvation, secreted HSP90α could be involved in the biological effects of serum starvation. As expected, serum starvation caused HCT-8 cell growth arrest (supplemental Fig. 2). The invasive ability of serum-starved HCT-8 cells was examined. In the Matrigel island invasion assay, serum-starved HCT-8 cells were seeded into the central part of a Matrigel island around which 10% fetal calf serum (10% FCS)-containing medium was added (Fig. 2A). Time-lapse photography was performed to monitor an 8-h process of HCT-8 cell invasion, and the data were analyzed by the Image-Pro Plus software. From the movement tracks shown in Fig. 2B, HCT-8 cells were more invasive after serum starvation as compared with cells maintained under normal conditions. The invasion distance of HCT-8 cells was quantified and is shown in Fig. 2, C and D. The data clearly indicate that serum starvation caused increases in both accumulated and oriented invasion distance of HCT-8 cells.

FIGURE 2.

HCT-8 cell invasion induced by serum starvation. A, setup of Matrigel island invasion assay. HCT-8 cells were serum-starved for 3 days and seeded into the central part of a Matrigel island around which 10% fetal calf serum (10% FCS)-containing medium was added. B, cell invasion tracks of normally growing or serum-starved HCT-8 cells. Time-lapse photography was performed to monitor an 8-h process of Matrigel island invasion. From the series of photos, we analyzed the movement tracks of 20 randomly selected normally growing or serum-starved HCT-8 cells by the Image-Pro Plus software. C, quantification of the accumulated and the oriented invasion distance of normally growing or serum-starved HCT-8 cells selected in B. val, value. D, comparison between normally growing and serum-starved HCT-8 cells about the average accumulated invasion distance and the average oriented invasion distance. The data are expressed as mean ± S.E., and differences in the data were considered significant if p < 0.05 (asterisk).

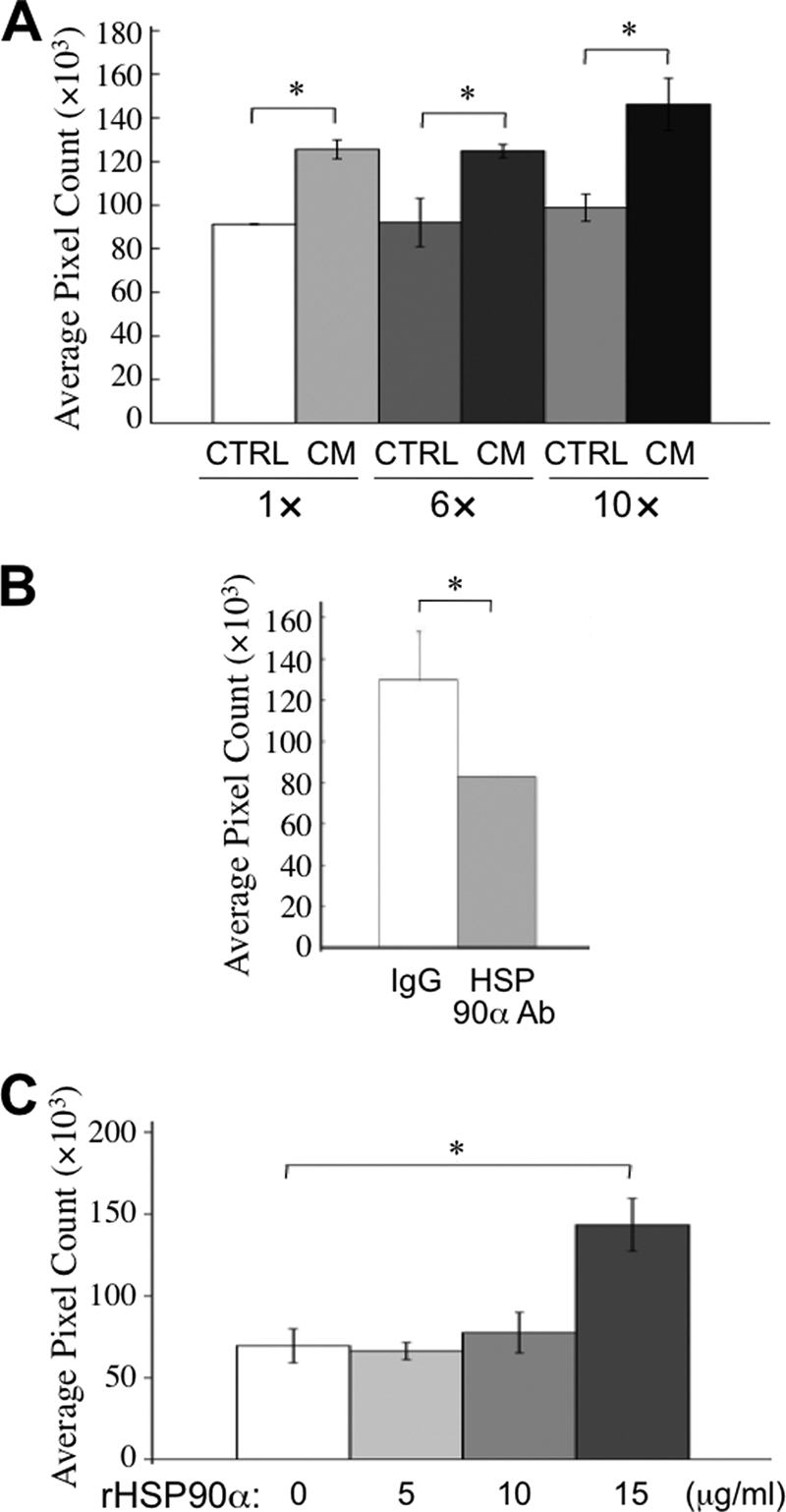

Next, the stimulatory role of secreted HSP90α in cancer cell migration was investigated. We collected CM from HCT-8 cells that had been serum-starved for 5 days and used CM to treat another normally cultured HCT-8 cells. The change of cell migration activity was analyzed by the conventional wound healing assay. The results revealed that CM significantly induced HCT-8 cell migration, and the induction was more obvious when 10× concentrated CM was used (Fig. 3A). This increased migration was inhibited in the presence of anti-HSP90α antibody (Fig. 3B), suggesting that HSP90α in CM was responsible for the induction of HCT-8 cell migration. Furthermore, HCT-8 cells were treated with serum-free medium plus 5, 10, or 15 μg/ml rHSP90α for the migration assay. The results showed that 15 μg/ml rHSP90α significantly induced HCT-8 cell migration (Fig. 3C), confirming that a sufficient amount of HSP90α secreted into serum-deficient medium is able to induce HCT-8 cell migration.

FIGURE 3.

HCT-8 cell migration enhanced by secreted HSP90α. A, HCT-8 cell migration is enhanced by serum starvation CM. HCT-8 cells were serum-starved for 5 days and incubated with fresh serum-free RPMI medium for another 24 h. The medium was collected as CM and was 6- or 10-fold concentrated by an Amicon Ultracel-30k centrifugal filter. On the other side, HCT-8 cells plated in 6-well plates were grown to confluence. After wounding with a white tip, cells were washed twice with PBS and treated with original or concentrated CM at 37 °C for 16 h. Pictures were taken of cells that migrated into the wounded area, and results were quantified by the Image-Pro Plus version 5.0.2 software. The serum-free RPMI medium, which was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, was used as control medium (CTRL). B, secreted HSP90α is involved in CM-induced HCT-8 cell migration. Confluent and wounded HCT-8 cells were treated with 10-fold concentrated CM in the presence of anti-HSP90α antibody. IgG (preimmune anti-rabbit immunoglobulin) was used as a control antibody. C, HCT-8 cell migration is enhanced by rHSP90α. To assay the enhancement of HCT-8 cell migration, confluent and wounded HCT-8 cells were treated with 5, 10, or 15 μg/ml rHSP90α. The data are expressed as mean ± S.E., and differences in the data were considered significant if p < 0.05 (asterisk).

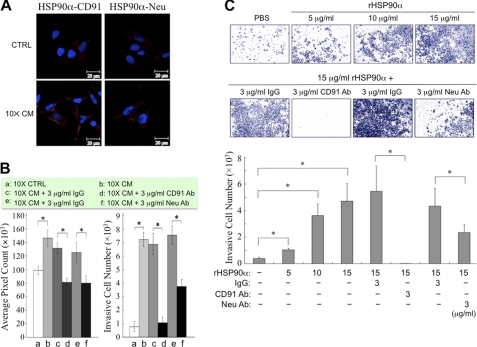

CD91 and Neu Involved in HSP90α-induced Cancer Cell Migration and Invasion

Secretion of HSP90α has been reported to promote both epidermal and dermal cell migration through the receptor CD91/LRP-1 (11). HSP90 localized to the cell surface also interacts directly with Neu/HER-2 and thus participates in heregulin-induced cancer cell invasion (7). We therefore hypothesized that CD91 and Neu may be involved in ectopic HSP90α-induced cancer cell migration and invasion. We first investigated whether HSP90α could directly interact with CD91 and Neu. After 10× CM treatment for 16 h, HCT-8 cells were double-stained with anti-HSP90α antibody and an antibody against CD91α or Neu followed by the proximity ligation assay. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole, and the images were obtained by confocal microscopy (Fig. 4A). Red fluorescence, which represents the direct contact between HSP90α and CD91α, was significantly increased after 10× CM treatment. The direct contact of HSP90α with Neu was also increased after 10× CM treatment, but the level was much less than that with CD91α.

FIGURE 4.

Involvement of CD91α and Neu in HSP90α-induced cancer cell migration and invasion. A, direct interaction of HSP90α with CD91α and Neu. HCT-8 cells were treated with 10× CM for 16 h and then double-stained with anti-HSP90α antibody and the antibody against CD91α or Neu followed by the proximity ligation assay. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole, and the images were obtained by confocal microscopy. The red fluorescence resulted from the direct contact of HSP90α with CD91α or Neu. B, CD91α and Neu are involved in 10× CM-induced HCT-8 cell migration and invasion. HCT-8 cells were treated with 10× CM in the presence of anti-CD91α or anti-Neu antibody for assaying cell migration (by conventional wound healing assay, left panel) and cell invasion (by Transwell invasion assay, right panel). CTRL, control medium. C, CD91α and Neu are involved in rHSP90α-induced HCT-8 cell invasion. HCT-8 cells, treated with rHSP90α in the presence of anti-CD91α (CD91 Ab) or anti-Neu antibodies (Neu Ab), were seeded in the top chambers of the Transwell inserts. Cells were allowed to invade for 24 h through Matrigel toward RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS in the bottom chambers. The filters of Transwell inserts were then fixed and stained with Giemsa, pictures were taken of the invasive cells on the filters (upper panel), and cells were counted by the Image-Pro Plus software (bottom panel). In B and C, the data are expressed as mean ± S.E., and differences in the data were considered significant if p < 0.05 (asterisk).

Furthermore, our results revealed that HCT-8 cell migration and invasion induced by 10× CM could be inhibited to different extents by treatment with anti-CD91α or anti-Neu antibodies (Fig. 4B). We also performed the experiments using rHSP90α instead of 10× CM. HCT-8 cell invasiveness increased with increasing concentrations of rHSP90α, which could be suppressed by the addition of anti-CD91α or anti-Neu antibodies (Fig. 4C).

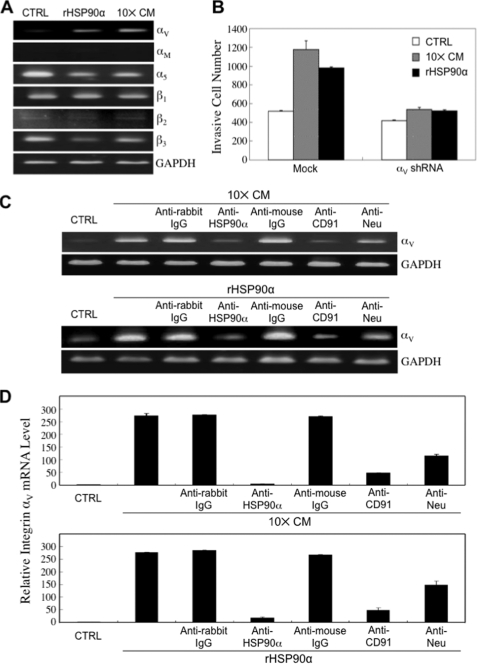

Integrin αV Involved in HSP90α-induced Cancer Cell Invasion

CD91/LRP-1 is a multifunctional scavenger and signaling receptor that interacts with more than 30 structurally unrelated proteins (13). Integrins are one group of proteins that interact with and are regulated by CD91 and function in cancer cell migration and invasion. We observed that both rHSP90α and 10× CM could selectively induce mRNA expression of integrin αV but not other tested integrins including αM, α5, β1, β2, and β3 (Fig. 5A). Induction of HCT-8 cell invasion by rHSP90α or 10× CM was significantly blocked when cells stably expressed integrin αV shRNA (Fig. 5B), suggesting that integrin αV was involved in rHSP90α and 10× CM-induced HCT-8 cell invasion. As expected, both rHSP90α-induced and 10× CM-induced integrin αV expression could be antagonized by anti-HSP90α, anti-CD91α, or anti-Neu antibodies (Fig. 5C). In parallel with the cell invasion study, anti-CD91α and anti-Neu antibodies exhibited different levels of antagonism in integrin αV expression (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, we investigated which signaling pathway(s) were responsible for 10× CM- and rHSP90α-induced integrin αV expression. When HCT-8 cells were treated with 10× CM or serum-free medium plus 15 μg/ml rHSP90α for 2 h, cellular levels of phosphorylated (P) (active) ERK, Akt, and NF-κB p65 were elevated (Fig. 6A). Using inhibitors against signaling pathways including ERK, JNK, p38, PI3K, and NF-κB, both 10× CM-induced and rHSP90α-induced integrin αV expression were significantly suppressed by the NF-κB inhibitor but not other inhibitors (Fig. 6B), suggesting that secreted HSP90α induced cellular integrin αV expression via a NF-κB-mediated pathway.

FIGURE 5.

Integrin αV involved in HSP90α-induced cancer cell invasion. A, induction of integrin αV mRNA by rHSP90α and 10× CM. The mRNA levels of integrin αV, αM, α5, β1, β2, and β3 were analyzed by RT-PCR in HCT-8 cells treated with 10× CM or 15 μg/ml rHSP90α for 16 h. Both rHSP90α and 10× CM induced the mRNA expression of integrin αV but not other tested integrins. The representative results from three independent experiments are shown. CTRL, control medium; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. B, expression of integrin αV is involved in rHSP90α and 10× CM-induced HCT-8 cell invasion. Induction of cell invasiveness by rHSP90α or 10× CM was drastically blocked when integrin αV shRNA was stably expressed in HCT-8 cells (p = 0.004 and 0.021, respectively). The data are the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. C, CD91 and Neu are involved in HSP90α-induced integrin αV expression. HCT-8 cells were treated 16 h with 10× CM or 15 μg/ml rHSP90α in the presence of 3 μg/ml anti-HSP90α, anti-CD91α, or anti-Neu antibodies for assaying the levels of integrin αV mRNA expression. The representative results from three independent experiments are shown. D, results of the quantitative RT-PCR analyses of the integrin αV mRNA levels in HCT-8 cells treated with 10× CM or 15 μg/ml rHSP90α in the presence of 3 μg/ml anti-HSP90α, anti-CD91α, or anti-Neu antibodies. The data are the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

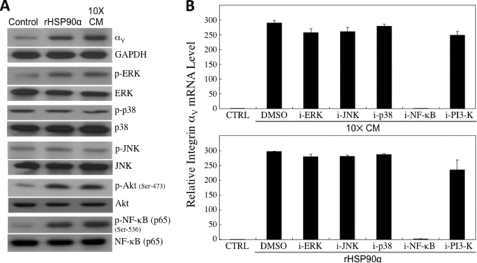

FIGURE 6.

NF-κB-mediated signaling pathway involved in 10× CM- and rHSP90α-induced integrin αV expression. A, Western blot analyses of the phosphorylated (P) (active) levels of ERK, JNK, p38MAPK, Akt, and NF-κB p65 in HCT-8 cells treated with 10× CM or serum-free medium plus 15 μg/ml rHSP90α for 2 h. The representative results from three independent experiments are shown. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. B, results of the quantitative RT-PCR analyses of the integrin αV mRNA levels in HCT-8 cells treated with 10× CM or 15 μg/ml rHSP90α in the presence of the inhibitors against ERK (PD98059, 5 μm), JNK (SP600125, 5 μm), p38MAPK (SB202190, 5 μm), NF-κB (6-amino-4-(4-phenoxyphenylethylamino) quinazoline, 100 nm), or PI3K (Ly294002, 50 μm) pathways. Both 10× CM-induced and rHSP90α-induced integrin αV expression were blocked only by the NF-κB inhibitor but not other inhibitors. The data shown are the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

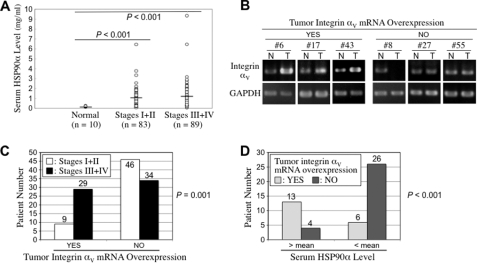

Tumor Integrin αV mRNA Overexpression Correlated with CRC Staging

Besides HCT-8 cells, rHSP90α also induced colorectal cancer cell invasion in other cell lines such as HCT-116 and SW480 (supplemental Fig. 3). In the clinic, we analyzed serum HSP90α levels from 10 normal volunteers and 172 CRC patients. The mean of normal volunteers was 0.18 ± 0.05 mg/ml, which was significantly lower than that of CRC patients (1.09 ± 1.14 mg/ml, p < 0.001). The HSP90α levels of low stage (TNM I + II) patients and high stage (TNM III + IV) patients were 1.00 ± 0.93 and 1.17 ± 1.30 mg/ml, respectively. The difference between low stage and high stage patients was not statistically significant (p = 0.328, Fig. 7A). Additionally, to ascertain whether increased integrin αV expression occurred in CRC patients and correlated with more invasive staging, we analyzed integrin αV mRNA levels from paired tumor and non-tumor tissues of 118 CRC patients. Representative results from six patients are shown in Fig. 7B. Thirty-eight of 118 (32.2%) patients exhibited elevated levels of integrin αV mRNA in the tumor tissues as compared with adjacent non-tumor tissues. Pearson chi-square analysis revealed that tumor integrin αV mRNA overexpression was significantly correlated with TNM staging (p = 0.001, Fig. 7C). In our total 241 patients, only 49 patients contributed both their serum specimens and their tissue specimens. Among these cases, 19 (38.8%) patients exhibited tumor integrin αV mRNA overexpression, and their serum HSP90α levels were also significantly higher than those from patients without tumor integrin αV overexpression (0.40 ± 0.19 versus 0.26 ± 0.07 mg/ml, p = 0.009). When the mean value (0.31 mg/ml) was used as the cut-off, 13 (76.5%) of 17 patients with higher serum HSP90α levels (> mean) had tumor integrin αV overexpression. For those 32 patients with lower HSP90α levels (< mean), only six (18.8%) patients expressed elevated levels of integrin αV mRNA in the tumor tissues (Fig. 7D). Pearson chi-square analysis revealed that higher serum HSP90α levels were significantly correlated with tumor integrin αV mRNA overexpression (r = 0.564, p < 0.001).

FIGURE 7.

Elevated serum HSP90α levels and tumor integrin αV overexpression in CRC patients. A, serum HSP90α levels were detected from 10 normal volunteers and 172 CRC patients. Normal volunteers had an average HSP90α level of 0.18 ± 0.05 mg/ml, which was significantly lower than that of CRC patients (1.09 ± 1.14 mg/ml, p < 0.001). The HSP90α levels of low stage (TNM I + II) patients and high stage (TNM III + IV) patients were 1.00 ± 0.93 and 1.17 ± 1.30 mg/ml, respectively. The difference between low stage and high stage patients was not statistically significant (p = 0.328). B, increased integrin αV mRNA expression occurred in the tumor tissues of CRC patients. The mRNA levels of integrin αV were analyzed from paired tumor (T) and non-tumor (N) tissues of 118 CRC patients. The results from six patients are shown as representative examples. Quantitative RT-PCR analyses of integrin αV mRNA levels were performed and normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Tumor integrin αV was considered to be overexpressed if the integrin αV level of tumor tissue was at least 2-fold higher than that of the corresponding non-tumor tissue. C, the Pearson chi-square analysis reveals that tumor integrin αV mRNA overexpression was significantly correlated with the TNM staging of CRC (p = 0.001). D, higher serum levels of HSP90α were significantly correlated with tumor integrin αV mRNA overexpression. Forty-nine patients were analyzed for levels of both serum HSP90α and tissue integrin αV mRNA. The Pearson chi-square analysis reveals that patients with higher serum HSP90α levels significantly exhibited elevated levels of integrin αV mRNA in their tumor tissues as compared with adjacent non-tumor tissues (r = 0.564, p < 0.001). Tumor integrin αV overexpression occurring in this patient group was significantly associated with the TNM staging of CRC (p = 0.004).

DISCUSSION

Human colon cancer HCT-8 cells secreted HSP90α and increased cell invasiveness in response to serum starvation stress. Our study further demonstrated that secreted HSP90α was an inducer of cancer cell migration and invasion. When a solid tumor grows beyond 2 mm in diameter, simple diffusion of nutrients and oxygen to metabolizing tissues is obviously insufficient so as that nutrient deficiency and hypoxia occur in multiple areas of tumor tissue. Many factors are produced within these areas to enhance angiogenesis or tumor cell spreading. Our data suggest that HSP90α could be one of these factors. Therefore, we analyzed serum levels of HSP90α from 10 normal volunteers and 172 CRC patients. Serum HSP90α levels of CRC patients were significantly higher than those of normal volunteers (p < 0.001). Furthermore, high stage (TNM III + IV) patients had higher HSP90α amounts in serum as compared with low stage (TNM I + II) patients, but the difference did not reach a statistically significant level. These results suggest that elevated HSP90α secretion occurs and affects CRC progression from earlier stages. Serum levels of HSP90α could potentially be used as an adjuvant diagnostic marker for colorectal neoplasia.

HSP90 is a molecular chaperone that facilitates proper folding and intracellular trafficking of numerous client proteins (1). Recent studies have shown that HSP90 is not only expressed in the cytoplasm and cell surface, but it can also be secreted by keratinocytes and cancer cells (8–12). Because of the lack of N-terminal signaling sequence, its secretion has been thought to be via an unconventional manner. Some reports have revealed that HSP90α can be exported from cells by exocytosis via nano-vesicles at the plasma membrane called exosomes (8, 14–16). Additionally, phosphorylation of Thr-90 residue and interaction of the last four residues with protein phosphatase 5 have been thought to regulate HSP90α secretion (12). The mechanism of HSP90α secretion after serum starvation remains to be investigated.

It has been reported that cell surface HSP90α has a stimulatory role in cancer cell migration and invasion (2), which is at least partly attributed to the interaction between HSP90α and Neu (7). In our experiments, secreted or ectopic HSP90α enhanced HCT-8 cell migration and invasion via a physical interaction with cell surface CD91 rather than Neu, and the induced migration and invasion could be drastically abolished by treatment with anti-CD91 antibody. Indeed, CD91 has been known as a common receptor for HSP90, HSP70, GP96, and calreticulin (17). The involvement of secreted HSP90α in cell migration and invasion through CD91 has also been demonstrated in skin cells during wound healing (9, 11). In addition, the Toll-like receptor TLR-4 serves as a HSP90 receptor in antigen-presenting cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells in response to bacterial infection (18), and annexin II is another cell surface HSP90α-binding protein in endothelial cells (19). In our study, the anti-Neu antibody could prevent to some extent HCT-8 cell migration and invasion induced by secreted HSP90α, revealing that Neu participates in the function of secreted HSP90α. It remains to be studied whether TLR-4 and annexin II are also involved in HSP90α-induced cancer cell migration and invasion.

CD91 is a cell membrane protein with multiple functions (13). It is involved in cell endocytosis. It also functions as a receptor for α2-macroglobulin, transforming growth factor-β, and a variety of other ligands. CD91 has been shown to interact with many other cell membrane-associated proteins such as integrins. Integrins are a family of cell membrane receptors composed of non-covalently bound α and β subunits (20). Once bound by ligands or cellular counterreceptors, integrins gather many other proteins to form a focal adhesion complex. Some known signaling pathways and some undiscovered signaling pathways are thus triggered to regulate cell survival, proliferation, cell shape changes, adhesion, migration, and invasion. Our data have demonstrated that integrin αV expression was selectively induced by secreted HSP90α and that HSP90α-induced cell invasion could be drastically prevented by shRNA-mediated specific knockdown of integrin αV. The association of integrin αV with CRC malignancy was further confirmed by data from our clinical investigation, which demonstrated that tumor integrin αV mRNA overexpression was significantly correlated with the TNM staging of cancer patients. In the literature, integrin αV seems to be particularly important in angiogenesis (21). The integrin αVβ3 heterodimer was overexpressed in the vasculature of colon carcinomas and served as marker of tumor-associated blood vessels (22). It is still unclear which β integrin can dimerize with αV to contribute to HSP90α-induced cancer cell invasion.

Antibodies against CD91 and Neu exhibited different efficacies in preventing HSP90α-induced integrin αV expression, suggesting that CD91 and Neu were differentially involved in integrin αV induction. Additionally, we also investigated the signaling pathway responsible for HSP90α-induced integrin αV expression. Although rHSP90α induced the activities of ERK, PI3K/Akt, and NF-κB p65, rHSP90α-induced integrin αV expression was suppressed only by the inhibitor of NF-κB p65 activation. Taking these results together, we conclude that secreted HSP90α can stimulate HCT-8 cell invasion by inducing integrin αV expression via a CD91- and NF-κB-dependent pathway. Activation of the NF-κB pathway as a downstream event of CD91 has also been revealed in GP96-treated plasmacytoid dendritic cells (23). However, the detailed mechanism regarding NF-κB activation by CD91 still needs to be explored.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Integrin αV shRNA was obtained from the National RNAi Core Facility sponsored by the National Research Program for Genomic Medicine Grants (NSC Grant 97-3112-B-001-016).

This work was supported by Grants CA-097-PP-13 and CA-098-PP-10 from the National Health Research Institutes, Grant CMRPG361691 from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, and Grant DOH99-TD-C-111-004 from the Department of Health, Taiwan, Republic of China.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–3.

- HSP90α

- heat shock protein 90α

- rHSP90α

- recombinant HSP90α

- PI3K

- phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- CRC

- colorectal cancer

- CM

- conditioned medium

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- JNK

- c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- TNM

- tumor, node, metastasis

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- RT-PCR

- reverse transcription-PCR

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gething M. J., Sambrook J. (1992) Nature 355, 33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsutsumi S., Neckers L. (2007) Cancer Sci. 98, 1536–1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goetz M. P., Toft D. O., Ames M. M., Erlichman C. (2003) Ann. Oncol. 14, 1169–1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sidera K., Samiotaki M., Yfanti E., Panayotou G., Patsavoudi E. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45379–45388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker B., Multhoff G., Farkas B., Wild P. J., Landthaler M., Stolz W., Vogt T. (2004) Exp. Dermatol. 13, 27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eustace B. K., Sakurai T., Stewart J. K., Yimlamai D., Unger C., Zehetmeier C., Lain B., Torella C., Henning S. W., Beste G., Scroggins B. T., Neckers L., Ilag L. L., Jay D. G. (2004) Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 507–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sidera K., Gaitanou M., Stellas D., Matsas R., Patsavoudi E. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 2031–2041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hegmans J. P., Bard M. P., Hemmes A., Luider T. M., Kleijmeer M. J., Prins J. B., Zitvogel L., Burgers S. A., Hoogsteden H. C., Lambrecht B. N. (2004) Am. J. Pathol. 164, 1807–1815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li W., Li Y., Guan S., Fan J., Cheng C. F., Bright A. M., Chinn C., Chen M., Woodley D. T. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 1221–1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu A., Tian T., Hao J., Liu J., Zhang Z., Hao J., Wu S., Huang L., Xiao X., He D. (2007) J. Cancer Mol. 3, 107–112 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng C. F., Fan J., Fedesco M., Guan S., Li Y., Bandyopadhyay B., Bright A. M., Yerushalmi D., Liang M., Chen M., Han Y. P., Woodley D. T., Li W. (2008) Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 3344–3358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X., Song X., Zhuo W., Fu Y., Shi H., Liang Y., Tong M., Chang G., Luo Y. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 21288–21293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lillis A. P., Van Duyn L. B., Murphy-Ullrich J. E., Strickland D. K. (2008) Physiol. Rev. 88, 887–918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clayton A., Turkes A., Navabi H., Mason M. D., Tabi Z. (2005) J. Cell Sci. 118, 3631–3638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lancaster G. I., Febbraio M. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 23349–23355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu X., Harris S. L., Levine A. J. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 4795–4801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basu S., Binder R. J., Ramalingam T., Srivastava P. K. (2001) Immunity 14, 303–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Triantafilou M., Triantafilou K. (2004) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32, 636–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lei H., Romeo G., Kazlauskas A. (2004) Circ. Res. 94, 902–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hynes R. O. (2002) Cell 110, 673–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iivanainen E., Kähäri V. M., Heino J., Elenius K. (2003) Microsc. Res. Tech. 60, 13–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Max R., Gerritsen R. R., Nooijen P. T., Goodman S. L., Sutter A., Keilholz U., Ruiter D. J., De Waal R. M. (1997) Int. J. Cancer 71, 320–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Filippo A., Binder R. J., Camisaschi C., Beretta V., Arienti F., Villa A., Della Mina P., Parmiani G., Rivoltini L., Castelli C. (2008) J. Immunol. 181, 6525–6535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.