Abstract

Excessive weight gain has been reported to occur in captive cynomolgus macaques with little to no change in diet. Overweight body condition can result in development of hyperglycemia and type 2 diabetes and should be avoided. The purpose of this survey was to assess the prevalence of overweight cynomolgus macaques in North American research facilities, including breeding colonies and short-term and long-term facilities, and to describe current methods used to assess body condition. The survey consisted of 51 questions covering animal population demographics, body weight and body condition scoring, feeding, and behavior. Voluntary participants included veterinarians and animal care managers. Respondents from 13 facilities completed the survey, and information was collected on 17,500 cynomolgus macaques. The majority of surveyed facilities housed juvenile and young adult macaques. The reported prevalence of overweight (greater than 10% of ideal body weight) animals ranged between 0% and 20% and reportedly was more frequent in animals younger than 10 y. Most facilities had weight reduction strategies in place. Despite these programs, a significant proportion of animals were reported as being overweight. The results of this survey demonstrate that most North American facilities housing cynomolgus macaques recognize the importance of tracking body condition regularly. However, implementing effective weight reduction programs may be difficult in captive housing environments. Because of the potential for adverse health effects, facilities should have a means of regularly tracking body weight as well as an action plan for managing overweight animals.

Abbreviation: BCS, body condition score

In nonhuman primates, excessive weight gain has been observed to occur in captivity with little to no change in diet, particularly in the rhesus and cynomolgus macaque species.5,11,18 In rhesus macaques, this phenomenon has been well documented in animals older than 10 y.11,12 Obesity has been identified as an important potential health concern with advancing age in nonhuman primates. One study14 determined that middle-aged (13 through 17 y old) male and female rhesus macaques had higher body weights and body fat compared with older and younger females. As expected given the physiologic similarities between the species, obesity-related health conditions can occur in macaques as with humans.

Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus occur in cynomolgus and rhesus macaques.6, 8-9,16 Animals diagnosed with naturally occurring type 2 diabetes mellitus typically are obese.16 In addition, gestational diabetes has been reported to occur in cynomolgus macaques, with an apparent increased occurrence of type 2 diabetes mellitus after development of this condition.17 Captive primate colonies continue to be maintained for research purposes. As such, the tendency for animals housed long-term to become overweight needs to be managed.

Although the characteristics of overweight macaques have been studied extensively,11,12,13 efficient means to measure and identify overweight nonhuman primates has not yielded any single ‘gold-standard’ method across laboratories. Recent work using rhesus macaques as a model 3 has led to the development of a body condition scoring (BCS) method for nonhuman primates. This BCS method involved palpation of the hips, pelvis, subcutaneous fat deposits, and spinal and thoracic muscle mass of sedated animals. The reliability of this BCS method relative to other physical measurements of body fat or biochemistry parameters was not reported.

The characteristics and effects of excessive weight gain in cynomolgus and other macaque species have been well described.11,12,13 However, the effect of these conditions on the management of colonies of single- and group-housed macaques has not been documented in the literature. In North America, cynomolgus macaques are the most common primate species used in research. For example, the Canadian Council on Animal Care 2006 Animal Use Report2 indicates that of 4363 nonhuman primates used in research that year, 2303 (53%) were cynomolgus macaques. The purpose of the current study was to survey North American primate research facilities, including breeding colonies and short- and long-term facilities, to assess the prevalence of overweight cynomolgus macaques. In addition, the general feeding practices and methods to assess body condition used currently in facilities are described.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional survey was created to describe aspects related to population demographics, body weight tracking, overweight body condition, and feeding strategies for cynomolgus macaques housed in research facilities in North America. The questionnaire was geared specifically toward cynomolgus macaques. This survey was a component of a larger project examining excessive weight gain and hyperglycemia in captive cynomolgus macaques.

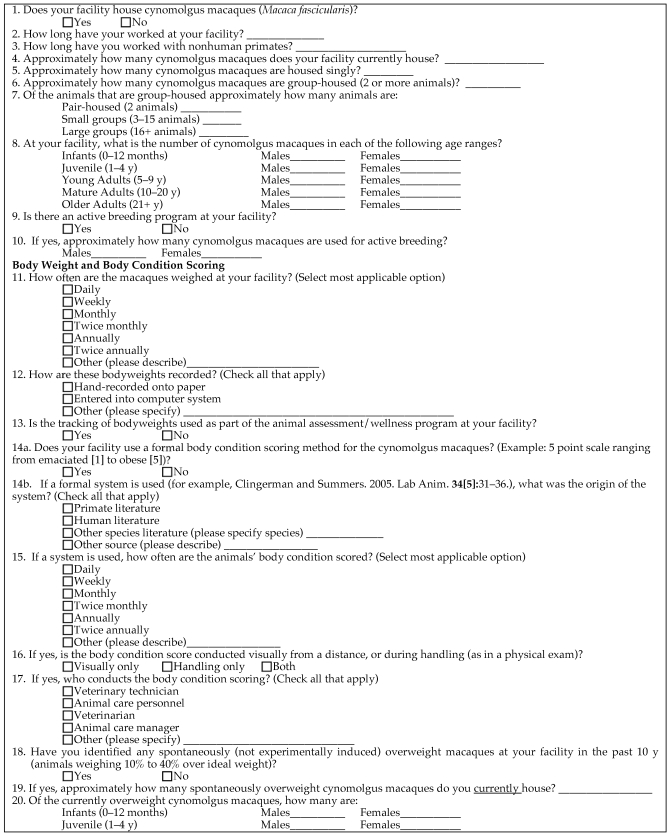

The survey was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Guelph. The Association of Primate Veterinarians' Board of Directors (http://www.primatevets.org/) was approached for permission to use their membership directory to contact potential respondents. The Board granted permission to conduct the survey, and endorsed the aims of the project. Facilities that housed large numbers of cynomolgus macaques were specifically sought for participation. The facility mandates included breeding colonies as well as private, government, and university research facilities in the United States and Canada. Eligible respondents included clinical veterinarians and animal care managers, who were contacted initially by email. Respondent information and institutional affiliation were kept strictly confidential. The survey (Figure 1) consisted of 51 questions in the subcategories of animal population demographics, body weight and BCS, feeding practices, and behavior.

Figure 1.

Survey administered to assess the prevalence of overweight body condition in cynomolgus macaques housed in North American research facilities.

For most questions, participants were given multiple response choices and the option to select ‘other’ and provide further detail. Questions dealing with numbers of animals were open-ended. In the survey, overweight body condition was defined as animals weighing at least 10% more than the ‘ideal’ weight for an adult male (6 to 9 kg) or adult female (3 to 6 kg) cynomolgus macaque. Surveys were conducted primarily by telephone interview during a prearranged appointment from July through September 2008. When an interview was not possible, surveys were returned by facsimile or email. Descriptive statistics were generated by using STATA version 9 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

We contacted 42 potential participants from 22 facilities; 4 facilities declined participation due to housing either none or few cynomolgus macaques at the time of the survey. Five facilities did not respond. A total of 15 participants representing 13 facilities completed the survey, for a facility response rate of 59%. Participants included 12 clinical veterinarians and 3 animal care managers. For each of 2 facilities, surveys were returned from 2 respondents: one veterinarian and one animal care manager. In both cases, questions pertaining to numbers of animals yielded similar or identical answers from the 2 respondents. Therefore, for summary purposes, results from 2 surveys from the same facility were combined into an overall facility response, except for questions that were opinion-oriented, in which case all 15 responses were included.

Population demographics.

Respondents had a minimum of 3.0 y and a maximum of 30 y (mean, 6.5 y) of experience working with nonhuman primates and had been working at their current facility from 0.5 to 16 y (mean, 14 y) at the time of this survey. Information was provided on approximately 17,500 cynomolgus macaques. Responses for animal populations ranged from exact numbers, to proportions given in percentages or by using terms such as ‘a few,’ ‘some,’ ‘all,’ ‘most,’ and ‘half.’ For summary purposes, results relating to population demographics are presented in percentages. Follow-up with participants that gave text responses assisted in categorizing the responses in the following manner: ‘a few,’ less than 5%; ‘some,’ 5% to less than 45%; ‘half,’ 45% to less than 60%; ‘most,’ 61% to 99%; and ‘all,’ 100%. Total facility populations of cynomolgus macaques ranged from approximately 60 to 4500 animals (mean, 1254). Of the 13 responding facilities, 6 had large cynomolgus macaque populations (more than 500 total animals), and 6 of 13 facilities had small cynomolgus macaque populations (fewer than 500 total animals). One facility did not report the total number of animals.

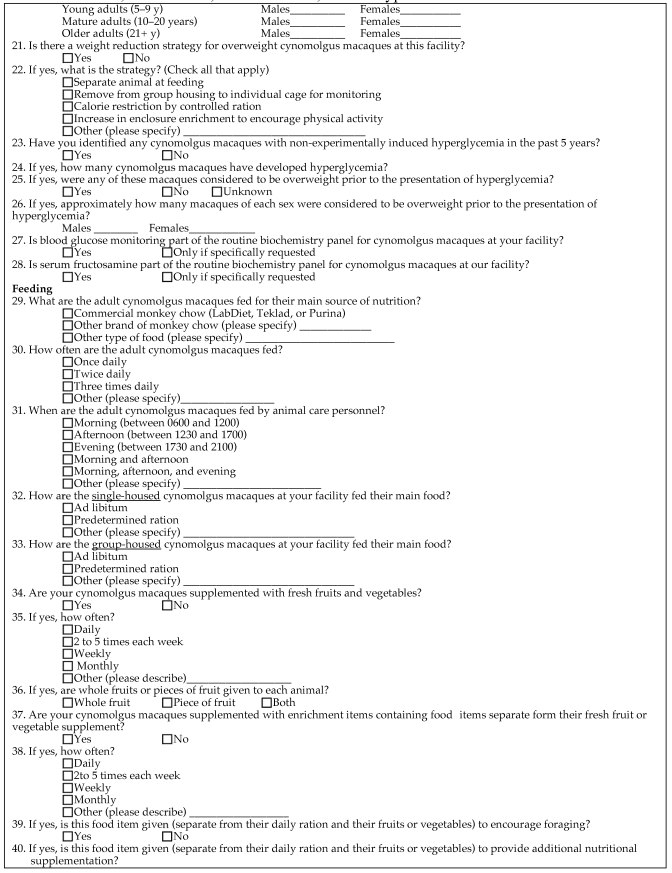

Figure 2 shows the general population distribution of cynomolgus macaques by age category from the participating facilities. Overall, the majority of the entire surveyed cynomolgus population was reported to be juveniles between 1 and 4 y of age (44%) and young adults between 5 and 9 y of age (41%), followed by mature adult females between 10 and 20 y of age (8%). Few mature adult males between 10 and 20 y of age, adults older than 21 y, and infants between 0 and 12 mo of age were reported (less than 4% respectively). Two respondents from 2 facilities that housed mostly young adult cynomolgus macaques felt that some animals were likely closer to the mature adult category. Two facilities had active breeding programs for cynomolgus macaques. Overall, the majority of the surveyed population of macaques was housed individually. A total of 11 of 13 facilities reported having a portion of macaques that were housed individually, and 8 of 11 facilities housed 50% to 100% of animals individually. Four facilities reported having 75% to 100% of their macaques housed in pairs or groups.

Figure 2.

Population distribution, using means of each age category, of (A) male and (B) female cynomolgus macaques at North American research facilities (n = 13) according to a survey of the prevalence of overweight body condition in laboratory-housed cynomolgus macaques.

Body weight and BCS.

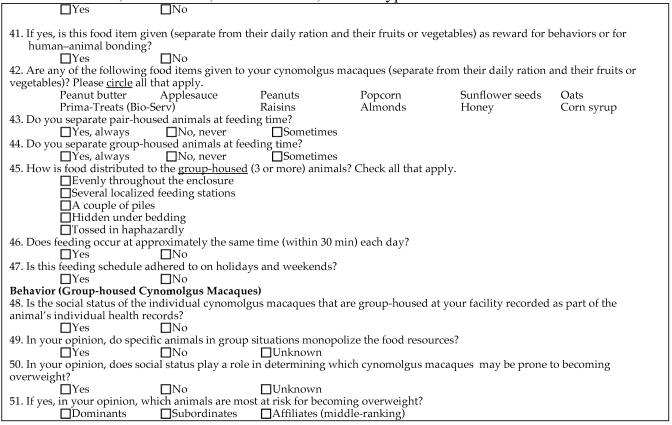

Overweight macaques (animals weighing 10% to 40% more than their ideal weight) had been identified at 12 of 13 facilities within the past 10 y or since the respondents had been employed at their facility. Eleven facilities reported having overweight animals at the time of the survey. Responses for the current population of overweight animals ranged from exact numbers to proportions given in percentages or by using terms such as ‘a few,’ ‘some,’ or ‘most.’ For summary purposes, results relating to overweight populations are presented in percentages. Follow-up with participants that gave text responses assisted in categorizing the responses in the following manner: ‘a few’ = < 3%, ‘some’ = 3% to less than 10%, and ‘most’ = greater than or equal to 10%. The percentage of overweight animals per facility ranged from 0% to 20% (Figures 3 and 4). In 10 of 13 facilities (77%), less than 3% of the current macaque population was evaluated as being overweight. This value represents approximately 300 total affected animals and ranges between 0 and 90 overweight animals per facility based on the population sizes indicated in the demographic questions. Two of 13 facilities identified between 10% and 20% of their animals as overweight (8 to 33 total macaques), and one facility identified up to 10% of their population (8 animals) as being overweight at the time of the survey. The majority of overweight animals were young adults between 5 and 9 y of age in 6 facilities, and in 5 facilities the majority of overweight animals were mature adults between 10 and 20 y of age. Weight reduction strategies were in place at 7 of 12 facilities.

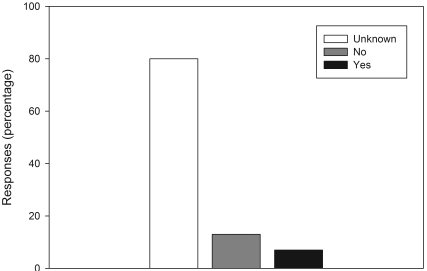

Figure 3.

Current estimated percentage of overweight body condition in cynomolgus macaques at North American research facilities (n = 13) according to a survey of the prevalence of overweight body condition in laboratory-housed cynomolgus macaques.

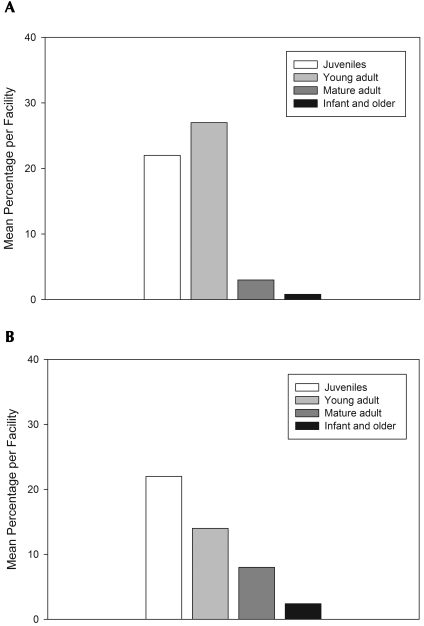

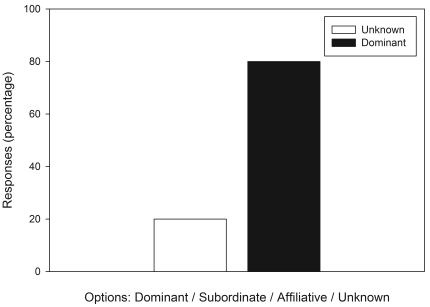

Figure 4.

Participant responses (n = 15) to 2 opinion questions regarding social status and overweight body condition in cynomolgus macaques according to a survey of the prevalence of overweight body condition in laboratory-housed cynomolgus macaques. (A) Does social status influence body condition? (B) Which social rank would most likely be associated with overweight condition? The options ‘affiliate’ and ‘subordinate’ were not selected by any of the respondents.

The main strategy described to reduce excessive body weight was calorie restriction. In addition, 10 of 13 facilities included blood glucose levels as part of routine biochemistry panels used to monitor macaque health. Two facilities identified animals with naturally occurring hyperglycemia within the previous 5 y. One of these facilities indicated that the animals were considered to be overweight prior to presentation of hyperglycemia. The body condition status of the hyperglycemic macaques at the second facility was unknown.

Tracking body weight was used as part of the animal assessment and wellness program at all facilities surveyed. Responses varied as to how often colony animals were weighed, with about half (46%) of the facilities weighing colony monkeys every 3 mo (quarterly). Other responses included twice annually, 3 to 6 times annually, bimonthly, monthly, or biweekly. Ten of 13 facilities used BCS to evaluate body condition. Most respondents (80%) cited primate literature as the reference resource, with 3 specifying the recently developed BCS system.3 Generally, BCS was not recorded as frequently as body weights. For the majority of facilities (73%), veterinarians and veterinary technicians conducted BCS. Other responses for personnel responsible for BCS assessments included veterinarians alone (9%); animal care and veterinary technicians (9%); and veterinarians, veterinary technicians, and animal care manager (9%).

Feeding.

All facilities reported feeding animals a diet of standard commercially prepared monkey chow twice daily (morning and afternoon). The majority (92%) of facilities fed individually housed animals a predetermined amount of chow. For group-housed animals (2 or more monkeys), a predetermined ration of chow was used in 8 facilities, and ad libitum feeding was used at the remaining 5 facilities. Macaques were supplemented with fresh fruit and/or vegetables daily at 7 facilities and 2 to 5 times weekly at the remaining 6 facilities.

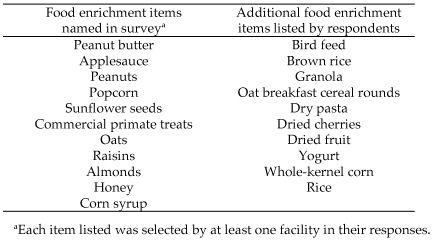

Additional food enrichment items were given at all facilities but not necessarily to all animals. The following items were used at 11 of 13 facilities: peanut butter, peanuts, popcorn, sunflower seeds, and raisins (Figure 5). Respondents listed anywhere from 1 to 50 items used in individual facility food enrichment programs. Responses varied markedly on regarding how long the animals received these food items. The majority of respondents gave food enrichment items 2 to 5 times weekly (n = 6) or weekly (n = 5). Two respondents specified that food enrichment was only given as needed to sick animals or monkeys exhibiting stereotypic behaviors. Most respondents indicated that food enrichment was given to encourage foraging behaviors (87%), reward positive behaviors, and encourage human–animal bonding (80%) but not for nutritional supplementation (93%).

Figure 5.

List of potential food enrichment items used by facilities.

Behavior.

At most facilities (7 of 13), social status of individual cynomolgus macaques was not recorded as part of each animal's individual health record. One respondent specified that social status was recorded in a separate behavioral record system. Respondents were asked whether, in their opinion, specific animals in group-housed situations monopolize the food resources. Of the 15 respondents, 11 (68%) indicated ‘yes,’ and the remaining 4 (32%) responded ‘no.’ Figure 4 represents the responses to the questions that asked whether, in the opinion of the survey participant, social status plays a role in determining which animals may be prone to becoming overweight, and if so, which animals were most at risk for becoming overweight. The majority of respondents (80%) felt that social status, specifically dominant status, is associated with increased risk of overweight body condition.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this survey is the first to assess the prevalence of overweight cynomolgus macaques within primate facilities in North America. Published information on rhesus macaques indicates that age is associated with overweight body condition, and middle-aged animals are most likely to be overweight.5,11,14 The respondents of this survey were overseeing cynomolgus macaque populations that mainly comprised juvenile to young adult animals between 1 and 9 y of age, and most of the facilities (10 of 13) reported few overweight animals at the time of the survey. However, even based on the low numbers of respondents, because of the population sizes at the facilities involved, the response still represents at least 300 overweight animals.

At 3 facilities reporting overweight animals, their prevalence was moderate to high, ranging from 9% to 20% of these macaque populations. In the facility with the highest reported prevalence, the majority of animals reported to be overweight were between 10 and 20 y old (mature adults), and most animals were housed in small groups of 3 to 15 animals. In the 2 facilities where 9% and 12% of animals were identified as overweight, and the majority of overweight animals were reported to be young adult males (5 to 9 y old). In these 2 facilities, most animals were housed in pairs or individually. Therefore, despite an awareness of health problems related to overweight body condition and practices in place to monitor body weights of all colony animals routinely, significant numbers of captive cynomolgus macaques are reported to have overweight body condition in North American facilities.

Most of the surveyed facilities indicated that calorie restriction was used to reduce weight in overweight cynomolgus macaques. Calorie restriction involves adjusting and strictly monitoring an animal's caloric intake in order to stabilize body weight. Studies have shown that calorie restriction lowers serum insulin levels and raises glucose tolerance in restricted animals.5 Beneficial effects of calorie restriction are increasingly being reported. In a long-term aging study in rhesus macaques, the onset of cancer and cardiovascular disease was reduced by 50%, and age-related brain atrophy was decreased in restricted animals compared with controls.4 How individual calorie restriction might be implemented effectively in a group-housing paradigm is unknown. However, strategies to individualize calorie intake may be necessary in captive colonies of mature adult cynomolgus macaques.

The results of this survey indicate that an overweight body condition was more common in young captive adult animals in North America, with 6 of 11 facilities (2 with moderate prevalence) observing this condition mainly in young adult macaques. Although the published data on overweight body condition in cynomolgus macaques are less extensive than those for rhesus macaques, excessive weight gain is generally accepted to have a gradual onset in adulthood, such that obesity is identified most often in middle-aged monkeys.5 The results of our survey raise interesting questions about overweight body condition in young captive cynomolgus macaques. Whether young adult animals were previously reported less readily is possible, or perhaps this pattern is associated with purpose-bred rather than wild-caught macaques. In addition, genetics may contribute to an overweight condition in young animals.

The small sample size of this survey precluded the identification of any clear patterns for prevalence of overweight macaques, with respect to variables such as social grouping style, breeding activity, and feeding practices. Food enrichment programs were implemented to some extent at all facilities, but whether this practice contributes to excessive weight gain in colony macaques could not be determined from this survey. A common factor among the 3 facilities with the highest reported numbers of overweight animals was that their cynomolgus macaque populations were smaller than 500 animals each. How macaque population size might affect body condition is unknown.

In the current survey, hyperglycemia was identified in 2 facilities where overweight mature adult cynomolgus macaques were reported. This finding is not surprising and is similar to the pattern seen in humans, in that impaired insulin function and glucoregulatory abnormalities that progresses into type 2 diabetes mellitus can take years to develop in macaques.17

Managing nonhuman primates in captivity requires providing living conditions to promote optimal physiologic and psychologic wellbeing. Social grouping for animal wellbeing has become an important aspect of maintaining primates in captivity.1,13 In the current survey, most respondents felt that social status may be a factor contributing to an animal's tendency to gain weight and that dominant animals specifically are at risk. These results may indicate a preconception that dominant animals are more prone to becoming overweight due to behavioral factors, such as priority access to resources. In addition, dominant animals may be more readily observed and evaluated within an enclosure, in that they may be more willing to approach caretakers. Little information has been published about the effect of social status on body condition and weight gain. Experiments have demonstrated the potential effect of the social hierarchy on physiologic parameters, but some studies indicate that among female animals, subordinate animals might be affected more.15 When cynomolgus macaques are fed high-fat diets in conjunction with experimental social reorganization, social rank is associated with physiologic changes. In females, these changes are seen as a high intraabdominal:subcutaneous abdominal fat ratio in subordinates.14 In males, an increase in coronary artery atherosclerosis was reported in dominants.10 Where pair- and group-housing are implemented, social status may need to be included in the health records of individual animals and taken into consideration when assessing changes in body condition.

Surveys can be useful for gaining insight into practices currently being used to house and care for primates in laboratory environments. Although we attempted to keep the survey succinct, some additional questions may have been useful. For example, the survey did not ask whether animals were mostly captive-bred or wild-caught. Details on the size of enclosures and whether animals were housed indoor or outdoor were not requested. In addition, survey questions did not address the average duration that macaques were maintained at each facility. A future survey could similarly target veterinarians, veterinary technicians, and animal care managers of other macaque species. Furthermore, extending the survey worldwide and targeting large breeding colonies might yield important information with respect to the prevalence of overweight body condition in captive primates.

In conclusion, the results of this survey indicate that most North American facilities housing cynomolgus macaques recognize the importance of tracking body condition regularly. The overall prevalence of overweight body condition was low in this surveyed population of cynomolgus macaques, with 8 of 11 facilities having less than 3% of their population overweight. Yet almost all of the respondents had observed overweight animals in the recent past, and the absolute numbers of animals affected was significant. Lower prevalence may have largely been affected by the young age of the majority of animals housed at the surveyed institutions. Overweight body condition reportedly is rare in facilities mostly housing juvenile and young adult macaques and was reported more frequently than expected in animals between 5 and 9 y. Body weight tracking and BCS systems are strategies currently used to monitor the health of captive cynomolgus macaques. Most facilities indicated that a weight reduction strategy was in place for overweight animals, but the effectiveness of these programs was difficult to gauge. According to the results of this survey, obesity is not a leading health problem in most facilities housing cynomolgus macaques. At facilities where macaques are maintained long-term or are middle-aged (older than 10 y), an increase in prevalence was apparent. Facilities that currently house mature adult macaques could take the lead in providing information regarding successful strategies to prevent or reverse excessive weight gain or naming risk factors leading to this condition in cynomolgus macaques.

Acknowledgment

We thank the Association of Primate Veterinarians' Board of Directors for their permission to administer this survey to association members.

References

- 1.Canadian Council on Animal Care 1993. Guide to the care and use of experimental animals, vol 1, 2nd ed, p 51–52, 64–70 Ottawa (Canada): Canadian Council on Animal Care [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian Council on Animal Care [Internet] 2006. Animal use report. [Cited June 29, 2010]. Available at: http://www.ccac.ca/en/Publications/New_Facts_Figures/table01/table01_index.htm

- 3.Clingerman KJ, Summers L. 2005. Development of a body condition scoring system for nonhuman primates using Macaca mulatta as a model. Lab Anim (NY) 34:31–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colman RJ, Anderson RM, Johnson SC, Kastman EK, Kosmatka KJ, Beasley TM, Allison DB, Cruzen C, Simmons HA, Kemnitz JW, Weindruch R. 2009. Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys. Science 325:201–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansen BC. 2001. Causes of obesity and consequences of obesity prevention in nonhuman primates and other animal models, p 181–201 : Bjorntorp P. International textbook of obesity. West Sussex (UK): John Wiley and Sons [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howard CF., Jr 1984. Diabetes mellitus: relationships of nonhuman primates and other animal models to human forms of diabetes, p 115–149 : Cornelius CE, Simpson CF. Advances in veterinary science and comparative medicine. Vol 28: research on nonhuman primates. Orlando (FL): Academic Press; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research 1996. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, p 21–51 Washington (DC): National Academies Press [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson MA, Lutty GA, McLeod DS, Otsuji T, Flower RW, Sandagar G, Alexander T, Steidl SM, Hansen BC. 2005. Ocular structure and function in an aged monkey with spontaneous diabetes mellitus. Exp Eye Res 80:37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones SM. 1974. Spontaneous diabetes in monkeys. Lab Anim 8:161–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan JR, Manuck SB, Clarkson TB, Lusso FM, Taub DM. 1982. Social status, environment, and artherosclerosis in cynomolgus monkeys. Arteriosclerosis 2:359–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kemnitz JW. 1984. Obesity in macaques: spontaneous and induced, p 81–114 : Cornelius CE, Simpson CF. Advances in veterinary science and comparative medicine. Vol 28: research on nonhuman primates. Orlando (FL): Academic Press; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kemnitz JW, Francken GA. 1986. Characteristics of spontaneous obesity in male rhesus monkeys. Physiol Behav 38:477–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kemnitz JW, Goy RW, Flitsch TJ, Lohmiller JJ, Robinson JA. 1989. Obesity in male and female rhesus monkeys: fat distribution, glucoregulation, and serum androgen levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 69:287–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramsey JJ, Laatsch JL, Kemnitz JW. 2000. Age and gender differences in body composition, energy expenditure, and glucoregulation of adult rhesus monkeys. J Med Primatol 29:11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shivley CA, Wallace JM. 2001. Social status, social stress and fat distribution in primates, p 203–211 : Bjorntorp P. International textbook of obesity. West Sussex (UK): John Wiley and Sons [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner JD, Cline JM, Shadoan MK, Bullock BC, Rankin SE, Cefalu WT. 2001. Naturally occurring and experimental diabetes in cynomolgus monkeys: a comparison of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism and islet pathology. Toxicol Pathol 29:142–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner JE, Kavanagh K, Ward GM, Auerbach BJ, Harwood HJ, Jr, Kaplan JR. 2006. Old World nonhuman primate models of type 2 diabetes mellitus. ILAR J 47:259–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young SS, Skeans SM, Austin T, Chapman RW. 2003. The effects of body fat on pulmonary function and gas exchange in cynomolgus monkeys. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 16:313–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]