Abstract

Angiogenesis has become an attractive target for drug therapy due to its key role in tumor growth. An extensive array of compounds is currently in pre-clinical development, with many now entering the clinic and/or achieving FDA approval. Several regulatory and signaling molecules governing angiogenesis are of interest, including growth factors (e.g. VEGF, PDGF, FGF, EGF), receptor tyrosine kinases, transcription factors such as HIF, as well as molecules involved in MAPK and PI3K signaling. Pharmacologic agents have been identified that target these pathways, yet for some agents (notably thalidomide), an understanding of the specific mechanisms of anti-tumor action has proved elusive. The following review describes key molecular mechanisms and novel therapies that are on the horizon for anti-angiogenic tumor therapy.

Keywords: angiogenesis inhibitors, hypoxia inducible factor (HIF), growth factors, VEGF, kinase inhibitors, anti-angiogenesis

In 1971, Dr Judah Folkman published a landmark paper in the New England Journal of Medicine, with the hypothesis that solid tumors caused new blood vessel growth (angiogenesis) in the tumor microenvironment by secreting pro-angiogenic factors1. This publication heralded the beginning of research on angiogenesis and hypoxia and their role in cancer. Over the last four decades, the discovery of a plethora of genes, signaling cascades and transcription factors has revealed the complexity of the angiogenic process and furthered our understanding of this hypothesis.

Inhibition of Angiogenesis for Anti-Cancer Purposes

Because angiogenesis is a key process to tumor growth, and a limited process in healthy adults, developing angiogenesis inhibitors is a desirable anti-cancer target where few side effects might be expected. Resistance to anti-angiogenesis drugs is also unlikely to occur, or at least at a much lower rate than seen with traditional cytotoxic chemotherapeutics, particularly if the genetically stable endothelial cells are targeted2. Selecting specifically for tumor endothelial cells and vessels could be achieved by targeting their unique or unusual properties. While physiologic angiogenesis is a tightly orchestrated process that is regulated by a balance of pro- and anti-angiogenic factors, tumor angiogenesis is erratic and irregular, with leaky vessels that are poorly formed (for review see references3,4,5). The tumor endothelial cells divide more rapidly than non-tumor endothelial cells and also express markers that the normal endothelial cells do not express2. Because endothelial cells line the blood vessels, they are also much more accessible to the circulation and therefore pharmacologic treatments than are the tumor cells themselves.

Advances in our understanding of the regulatory mechanisms that govern tumor angiogenesis continues to aid drug development, particularly with the identification of new therapeutic targets. An understanding of how both newly developed and conventional anti-cancer compounds function to inhibit angiogenesis will help further our understanding of how tumor angiogenesis occurs and how it might be successfully limited to halt the growth and spread of a tumor. One interesting finding is that many conventional chemotherapeutics actually possess previously unknown anti-angiogenesis activity. These include cytotoxic chemotherapeutic drugs, hormonal ablation therapies and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (for review see Kerbel et al.6).

The following review will give a broad overview of the key mechanisms involved in tumor angiogenesis and the various inhibitors that have shown promise for cancer therapy.

Process of Carcinogenesis and Subsequent Tumor Angiogenesis

The process of transformation from a normal cell into a cancer cell involves a series of complex genetic and epigenetic changes. In an influential paper, Hanahan and Weinberg proposed that six essential ‘hallmarks’ or processes were required for transformation of a normal cell to a cancer cell7. These processes include (i) self-sufficiency in growth signals, (ii) insensitivity to anti-growth signals, (iii) evasion of programmed death (apoptosis), (iv) endless replication potential, (v) tissue invasion and metastasis and importantly (vi) sustained angiogenesis7.

Initially, the growth of a tumor is fed by nearby blood vessels. Once a certain tumor size is reached, these blood vessels are no longer sufficient and new blood vessels are required to continue growth. The ability of a tumor to induce the formation of a tumor vasculature has been termed the ‘angiogenic switch’ and can occur at different stages of the tumor-progression pathway depending on the type of tumor and the environment4. Acquisition of the angiogenic phenotype can result from genetic changes or local environmental changes that lead to the activation of endothelial cells.

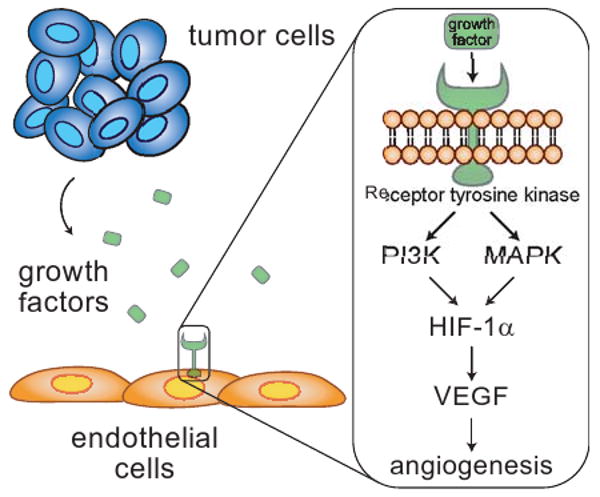

One way for a tumor to activate endothelial cells is through the secretion of pro-angiogenic growth factors which then bind to receptors on nearby dormant endothelial cells (ECs) that line the interior of vessels (figure 1). Upon EC stimulation, vasodilation and permeability of the vessels increase and the ECs detach from the extracellular matrix and basement membrane by secreting proteases known as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). The ECs then migrate and proliferate to sprout and form new branches from the pre-existing vasculature. The growth factors can also act on more distant cells recruiting bone-marrow derived precursor endothelial cells and circulating endothelial cells to migrate to the tumor vasculature (for an overview see references4,8).

Figure 1.

Tumor cells secrete pro-angiogenic growth factors that bind to receptors on dormant endothelial cells (ECs) leading to vasodilation and an increase in vessel permeability. The ECs migrate and proliferate to form new branches from the pre-existing vasculature by detaching from the extracellular matrix and basement membrane.

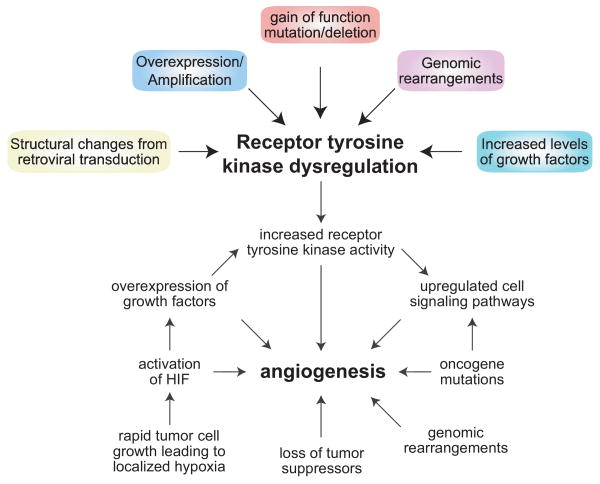

The pro-angiogenic growth factors may be overexpressed due to genetic alterations of oncogenes and tumor suppressors, or in response to the reduced availability of oxygen (figure 2). Tumor cell expression of many of the angiogenic factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is regulated by hypoxia through the transcription factor hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)9. As the tumor cells proliferate, oxygen becomes depleted and a hypoxic microenvironment occurs within the tumor. HIF is degraded in the presence of oxygen, so formation of hypoxic conditions leads to HIF activation and transcription of target genes. The strongest activation of HIF results from hypoxia, but several other factors can contribute to increased expression and activity of HIF, including growth factors and cytokines such as TNF-α10, IL-1β (interleukin-1β)11,10, EGF12,13, and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)14, which lead to increased cell signaling. Along similar lines, oncogenes that trigger increased expression of growth factors and overactive signaling pathways can increase HIF expression and activity. For example, mutant Ras can contribute to tumor angiogenesis by enhancing the expression of VEGF through increased HIF activity15,16. The oncogenes v-Src17 and HER218 and dysregulated PI3K and MAPK signaling pathways12,13,19,14,20 have also been shown to upregulate HIF expression and HIF transcriptional activity.

Figure 2.

Pathways and mechanisms that can lead to increased angiogenesis, including overexpression of growth factors and receptor tyrosine kinase dysregulation.

Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signaling

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are transmembrane proteins that mediate the transmission of extracellular signals (like growth factors) to the intracellular environment, therefore controlling important cellular functions and initiating processes like angiogenesis. Structurally, the RTKs generally consist of an extracellular ligand binding domain, a single transmembrane domain, a catalytic cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase region and regulatory sequences. RTKs are activated by the binding of a growth factor ligand to the extracellular domain, leading to receptor dimerization and subsequent auto phosphorylation of the receptor complex by the intracellular kinase domain, utilizing ATP21. The phosphorylated receptor then interacts with a variety of cytoplasmic signaling molecules, leading to signal transduction and eventually angiogenesis, among other processes involved in cell survival, proliferation, migration and differentiation of endothelial cells (for review see21,22).

RTKs that become dysregulated can contribute to the transformation of a cell. The dysregulation can occur through several different mechanisms, including (i) amplification and/or overexpression of RTKs, (ii) gain of function mutations or deletions that result in constitutively active kinase activity, (iii) genomic rearrangements that produce constitutively active kinase fusion proteins, (iv) constant stimulation of RTKs from high levels of pro-angiogenic growth factors and (v) retroviral transduction of a deregulating proto-oncogene that cause RTK structural changes, all of which lead to increased downstream signaling21.

The complex signaling network uses multiple factors to determine the biological outcome of the receptor activation. While the pathways are often depicted as linear pathways for simplicity, they are actually a network of pathways with various cross-talk and overlapping functions, as well as distinct functions. Some of the known signaling cascades include the PLCγ-PKC-Raf kinase-MEK-MAPK and PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathways and activation of the Src tyrosine kinases23,24,25,26. A detailed overview of the individual growth factors and their receptor tyrosine kinases is beyond the scope of this review, but some of the main factors will be briefly covered below.

VEGF

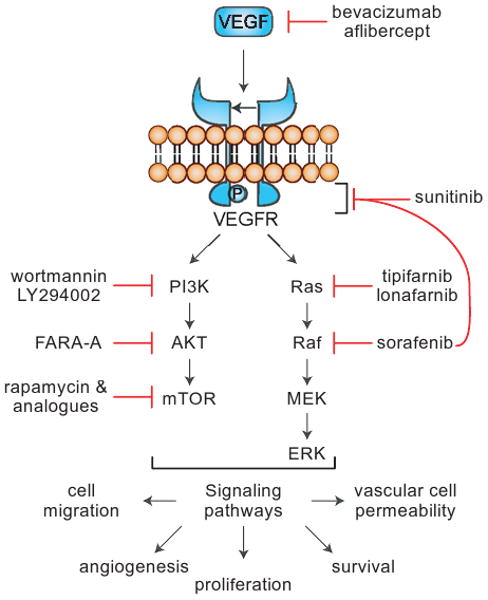

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor tyrosine kinase (VEGFR) play key roles in angiogenesis (figure 3; for review see references27,28,29,30). While VEGF is actually a family of at least seven members (table 1), the term VEGF typically refers to the VEGF-A isoform, one of the most studied members and a major mediator of tumor angiogenesis. VEGF-A is a pro-angiogenic factor that plays important roles in cell migration, proliferation, and survival. Four spliced isoforms of VEGF-A are known (VEGF121, VEGF165, VEGF189, and VEGF206), with VEGF165 being the most predominant form30. VEGF-A was initially identified for its ability to increase vascular permeability in guinea pigs, and was termed vascular permeability factor (VPF)31 and then separately identified for its ability to promote the growth of vascular endothelial cells, naming it VEGF32. Cloning the VPF and VEGF genes revealed that they were actually the same33,34.

Figure 3.

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) binds to the VEGF receptor, a receptor tyrosine kinase, leading to receptor dimerization and subsequent auto phosphorylation of the receptor complex. The phosphorylated receptor then interacts with a variety of cytoplasmic signaling molecules, leading to signal transduction and eventually angiogenesis. Examples of both pre-clinical and clinical compounds that inhibit the pathway are shown.

Table 1.

Select Growth Factors and Receptors

| Growth Factor | Function / Role | Members | Receptors |

|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) | Physiological blood vessel formation and pathological tumor angiogenesis | VEGF-A, -B, -C, -D, -E, and the placental growth factors (PLGF-1 and -2) | VEGFR-1 (Flt-1), VEGFR-2 (KDR/Flk-1) and VEGFR-3 (Flt-4) |

| PDGF (platelet derived growth factor) | Cell growth and division; blood vessel formation; pericyte and smooth muscle recruitment and proliferation | PDGF-A, -B, -C and –D that form the five active homo- and heterodimers: PDGF-AA, -AB, -BB, -CC and -DD | PDGF-α and -β |

| FGF (fibroblast growth factor) | Vascular endothelial cell proliferation, migration, development and differentiation | 23 members (FGF-1 through FGF-23) | FGFR-1, -2, -3 and -4 |

| EGF (epidermal growth factor) | Cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, angiogenesis and survival | EGF (epidermal growth factor), TGF-α (tumor growth factor-α), HB-EGF (heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor), AR (amphiregulin), BTC (betacellulin), epigen, epiregulin, neuregulins 1-4 | EGFR (ErbB1), HER2 (ErbB2/Neu), HER3 (ErbB3), and HER4 (ErbB4) |

| TGF-β (transforming growth factor) | Angiogenesis, cell regulation and differentiation, embryonic development, wound healing, growth inhibition properties | TGF-β1, -β2 and -β3 | type I, II, or III |

| Angiopoietin | Initiation and progression of angiogenesis; vessel maintenance, growth and stabilization | Ang-1, -2 and -3/4 | Tie-1 and -2 |

When VEGF is secreted from tumor cells, it interacts with cell-surface receptors, including VEGFR-1 and -2, located on vascular endothelial cells and bone-marrow derived cells. VEGFR-2 is believed to mediate the majority of the angiogenic effects of VEGF-A while the role of VEGFR-1 is complex and not fully understood30. A soluble form of VEGFR-1 can act as a decoy receptor, preventing VEGF-A from acting on VEGFR-2 and activating signaling pathways. However, there is also evidence that indicates VEGFR-1 plays an important role in developmental angiogenesis30. A third receptor, VEGFR-3, is involved in lymphangiogenesis and does not bind VEGF-A30.

VEGF-A165 is commonly overexpressed by a wide variety of human tumors and overexpression has been correlated with progression, invasion and metastasis, microvessel density and poorer survival and prognosis in patients35,36,37,38. VEGF-A and VEGFR-2 are currently the main targets for anti-angiogenesis efforts27.

PDGF

The family of platelet derived growth factors (PDGF) and receptors (PDGFR) are involved in vessel maturation and the recruitment of pericytes39. PDGF stimulates angiogenesis in vivo40,41, though the role of PDGF in angiogenesis is not fully understood (for review see references42,43). The family of PDGF ligands consists of four structurally related soluble polypeptides, that exist as homo- and hetero-dimers (table 1). There are two forms of the PDGF tyrosine kinase receptors, PDGFR-α and -β42. PDGF is expressed by endothelial cells and generally acts in a paracrine manner, recruiting PDGFR expressing cells, particularly pericytes and smooth muscle cells, to the developing vessels43.

Mutations involving upregulation of PDGF and/or PDGFR have been described in human cancers, though the role of these mutations in cancer has not been fully characterized43. Nearly all gliomas tested are positive for PDGF and PDGFR44,45 and overexpression of PDGFR has been associated with poor prognosis in ovarian cancer46, indicating a likely role for the PDGF pathway in human cancers.

FGF

The mammalian fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family is composed of 23 different proteins, which are classified into six different groups based on the similarity of their sequences (for review see references42,47). The FGF ligands were among the earliest angiogenic factors reported and are involved in promoting the proliferation, migration and differentiation of vascular endothelial cells48,49. FGF ligands have a high affinity for heparin sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs), which act as co-receptors by binding to both FGF and one of the four different fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFR) simultaneously47. The FGF receptor tyrosine kinases are widely expressed and are present on most, if not all, cell types, where they act through a wide range of biological roles42. FGFRs are often overexpressed in tumors and mutations of the FGFR genes have been found in human cancers, making it particularly significant that FGFR activation in endothelial cell culture and animal models leads to angiogenesis42,47. Overexpression of various FGF ligands in different types of tumors has been documented47. FGF-2, in particular, has been shown to possess potent angiogenic activity50 and is also commonly overexpressed in tumors and has been found to correlate with poor outcome in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and bladder carcinomas51,52.

EGF

The epidermal growth factor (EGF) family consists of eleven known members which bind to one of four epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR)53. All of the receptors, except HER3, contain an intracellular tyrosine kinase domain54. HER2 does not have any known ligands that bind with high affinity, despite it being a potent oncoprotein (for review see references53,54). Activation of EGFR has been linked to angiogenesis in xenograft models55, in addition to metastasis, cell proliferation, survival, and migration, transformation, adhesion and differentiation54. Because activation of the EGFR pathway upregulates the production of pro-angiogenic factors like VEGF, it can be viewed as more of an indirect regulator of angiogenesis, rather a direct regulator, making the role of the EGF/EGFR system less important to angiogenesis than more direct regulators, such as the VEGF and PDGF systems (reviewed in references53,54,56,57).

Other Angiogenic Factors

TGF-β

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and corresponding receptors are produced by nearly every cell type, though each of the three isoforms of TGF-β (TGF-β1, -β2, -β3) demonstrates a different tissue expression pattern58. TGF-β participates in angiogenesis, cell regulation and differentiation, embryonic development, and wound healing and also has potent growth inhibition properties58. The TGF-β receptors are classified as type I, II, or III. Type I and II receptors contain serine/threonine kinase domains in their intracellular protein regions, while type III does not possess kinase activity but thought to participate in transferring TGF-β ligands to type II receptors58. TGF-β ligands bind to and stimulate type II receptors that recruit, bind and phosphorylate type I receptors, activating downstream signaling proteins known as SMADs, which are believed to be specific to the TGF-β family. Activated SMADs eventually move to the nucleus where they can interact with different transcription factors, regulating gene expression in a cell-specific manner58. SMADs have been found to be mutated at a high rate in pancreatic and colorectal cancer, and are found in other cancers as well, indicating that SMAD mutations and aberrant regulation likely contribute to the development of cancers (reviewed in59). In addition to the SMADs, signaling mediated by TGF-β can involve activation of downstream targets such as MAPK and PI3K59.

TGF-β is thought to have both pro- and anti-angiogenic properties, depending on the levels present. Low levels of TGF-β contribute to angiogenesis by upregulating angiogenic factors and proteases, while high doses of TGF-β stimulate basement membrane reformation, recruit smooth muscle cells, increase differentiation and inhibit endothelial cell growth8. Tumor cells can also become resistant to TGF-β and will no longer respond to the growth-inhibiting properties, leading to tumor cell proliferation. Tumors that no longer respond to the growth inhibition signals from TGF-β can then exploit the abilities of TGF-β to regulate processes involved in angiogenesis, cell invasion and tumor cell interactions60.

Overexpression of TGF-β1 has been seen in gastric, breast, colon, hepatocellular, lung and pancreatic cancer and is correlated with tumor angiogenesis in addition to metastasis, progression and poor prognostic outcome61. High levels of endoglin, part of the TGF-β receptor complex, have also been detected in cancers and are associated with tumor metastasis60.

Angiopoietins and Tie Receptors

The angiopoietin ligands and Tie receptor tyrosine kinases play a regulatory role in vascular homeostasis and maintenance of quiescent endothelial cells in adults and are also an essential component of embryonic vessel assembly and maturation62. The angiopoietin (Ang) family of ligands (Ang-1, -2, and -3/-4) bind to the receptor tyrosine kinase Tie-2. No ligand has been identified yet for the Tie-1 receptor (for review see references62,63,64). Ang-1 behaves as an agonist, activating the Tie-2 receptor, while Ang-2 acts as an antagonist for Tie-265, though the role of Ang-2 in tumor angiogenesis is not fully understood and appears to be dependent on the environmental context. In the presence of VEGF-A, Ang-2 will promote angiogenesis, and in the absence of VEGF-A, Ang-2 will cause vessel regression66,67. Overexpression of Ang-2 has been found to correlate with increased angiogenesis, malignancy and aggressive tumor growth in some cancers, and in other tumor types, overexpression led to decreased tumor growth and metastasis and vessel regression (for review see62,63,64). The involvement of additional factors in Ang-2 function are likely the cause of conflicting data on Ang-2, indicating the need for further studies of the Ang/Tie system.

Ang-1 overexpression leads to vasculature that is more mature and normal in appearance, explaining the vessel-normalization effect that results from anti-VEGF/VEGFR therapies, as they these effects are mediated through Ang-168. Most studies have shown that Ang-1 possesses mostly anti-tumorgenic effects, though some have indicated that Ang-1 can stimulate tumor growth62.

While the angiopoietins and Tie receptors appear to play an important role during tumor angiogenesis, the specific mechanisms are controversial. A further understanding of the specific roles of the members of the Angiopoietin/Tie system may enable targeting of this system for anti-angiogenic and anti-cancer purposes.

Attempts at targeting the Tie-2 pathway for angiogenesis inhibition have had more difficultly than some of the other angiogenesis targets, such as VEGF, in part because of the lack of understanding as to the agonistic and antagonistic roles of Ang-1 and Ang-2 on the Tie-2 receptor. There have been some efforts though, and peptide-antibody fusions that bind and neutralize Ang-2 have been shown to decrease tumor growth and angiogenesis, and suppress endothelial cell proliferation in pre-clinical models69, demonstrating the feasibility of targeting Ang/Tie for anti-angiogenic purposes.

Delta/Jagged-Notch Signaling

The family of Notch receptors (Notch1-4) and their transmembrane ligands Delta-like (Dll1, 3, 4) and Jagged (Jagged1, 2) play important roles in cells undergoing differentiation, acting primarily to determine and regulate cell fate, as well as playing a part in developmental and tumor angiogenesis. In healthy mice, Dll4 is required for normal vascular development and arterial formation, while in tumor angiogenesis, Dll4 and Notch signaling appears to play a role in regulating the cellular actions of VEGF (for review see references70,71).

Activation of Notch signaling is dependent upon cell to cell interactions and occurs when the extracellular domain of the cell surface receptor interacts with a ligand found on a nearby cell. Lateral inhibition, one mechanism of Notch signaling, involves binding of a Notch ligand to a Notch receptor on an adjacent cell, which results in activation of the Notch signaling pathway in one cell and suppression in the other cell, resulting in two different fates for each cell70. Notch receptors also participate in transcriptional regulation through a unique mechanism involving cleavage of the intracellular domain of the Notch receptor, which then translocates to the nucleus where it can participate in transcriptional regulation71.

Delta-like 4 (Dll4) and Jagged1 have particularly been implicated in tumor angiogenesis, with strong expression of Dll4 seen in the endothelium of tumor blood vessels, and much weaker expression in nearby normal blood vessels72,73,74,75. The expression of Dll4 appears to be regulated directly by VEGF in the setting of tumor angiogenesis; increased levels of VEGF lead to increased expression of Dll475,76. Dll4 then signals to the Notch receptor-expressing endothelial cells to downregulate VEGF-induced sprouting and branching77. In this manner, Dll4 acts as a negative modulator of angiogenesis, regulating excessive VEGF-induced vessel branching, allowing vessel formation to occur at a productive and efficient rate77. Overexpression of Jagged1, a Notch ligand, is dependent on MAPK signaling78 and has been associated with angiogenic endothelial cells in vitro79. Jagged1 is thought to promote angiogenesis, as overexpression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) cells leads to increased vascularization and tumor growth78.

Attempts to manipulate Notch signaling for anti-cancer purposes have been studied, particularly through inhibition of Dll4. Interestingly, inhibition of Dll4 leads to an increase in tumor vascular density; this increase is likely due to the lack of downregulation of branching and sprouting caused by Dll474,80. However, even though an increase in vascularity is seen, the vascular network is very poorly formed and essentially non-functional (even more so than typical disorganized tumor vasculature) and a significant decrease in tumor size was observed74,80. The decrease in tumor size was seen even in tumor models that are resistant to VEGF-blockade, making inhibition of this pathway an attractive alternative for tumors that become resistant to VEGF inhibitors used in the clinic74,80. When Dll4 inhibition was combined with VEGF inhibition in tumors with no resistance, additional anti-tumor activity was seen than compared to inhibition of either factor alone80.

Inhibition of Jagged1 has also been studied. Knockdown of Jagged1 expression in SCC cells inhibits pro-angiogenic effects of the cells in vitro, even when the cells were stimulated with growth factors78. Another study looked at inhibition of Notch receptor function, using a soluble Notch1 receptor decoy that prevented Dll1, Dll4 and Jagged1 from binding to Notch receptors81. The decoy blocked angiogenesis in both in vitro and in vivo models, as well as causing a decrease in tumor growth using mammary xenografts81.

Inhibition of specific components of the Notch signaling pathway, such as Dll4 or Jagged1, or more broad inhibition of Notch signaling may prove to be effective for inhibiting functional angiogenesis and neovascularization in tumors and some of the pre-clinical studies appear promising. However, further studies are needed to better understand the role that Notch signaling and its individual components play in tumor angiogenesis before these pathways can be exploited for clinical use.

Hypoxia Inducible Factor

Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) is a transcription factor involved in cellular adaptation to hypoxia. HIF transcriptional activity is regulated by the presence of oxygen and becomes active in low oxygen conditions (hypoxia). HIF controls a large number of angiogenesis-involved genes (for review see references9,82). The active HIF complex consists of an α and β subunit in addition to coactivators including p300 and CBP. The HIF-β subunit (also known as ARNT) is a constitutive nuclear protein with further roles in transcription not associated with HIF-α. In contrast to HIF-β, the levels of the HIF-α subunits and their transcriptional activity are regulated by oxygen availability.

There are three related forms of human HIF-α (-1α, -2α and -3α), each of which is encoded by a distinct genetic locus. HIF-1α and HIF-2α have been the best characterized, possessing similar domain structures that are regulated in a related manner by oxygen, though each isoform does have distinct and separate roles. The role of HIF-3α is not fully understood, though a truncated form of murine HIF-3α known as inhibitory PAS domain protein (IPAS) has been found to act as an inhibitor of HIF via dimerization with HIF-β83.

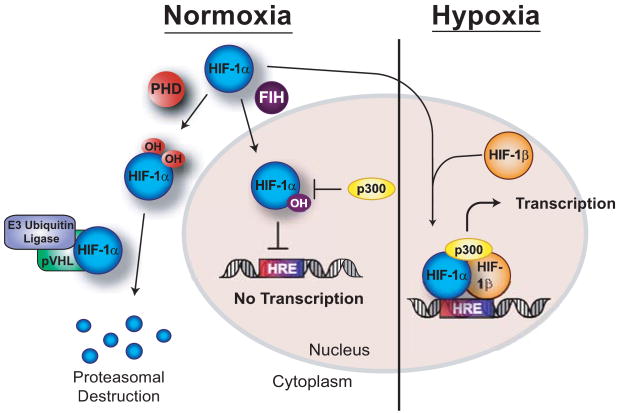

Both the HIF-α and HIF-β subunits are produced constitutively, but in normoxia HIF-1α and -2α are degraded by the proteasome in an oxygen-dependent manner. Hydroxylation of two prolines in HIF-α enables HIF-α to bind to the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein (pVHL), which links HIF-α to a ubiquitin ligase complex. The ubiquitin ligase catalyzes polyubiquitinylation of HIF-α, targeting it for degradation by the proteasome. In addition, hydroxylation of an asparagine residue in HIF-α disrupts the interaction between HIF-α and the coactivator p300, through a process independent of proteasomal degradation, which leads to reduced HIF transcriptional activity. In this manner, asparaginyl hydroxylation acts as a regulatory switch controlling the activity and specificity of HIF gene expression, as opposed to the prolyl-hydroxylations which control HIF-α stability (for review see83,84). In hypoxia, minimal to no hydroxylation occurs, enabling HIF-α to avoid proteasomal degradation and dimerize with HIF-β and coactivators, forming the active transcription complex on the hypoxia response element (HRE) associated with HIF target genes (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Both the HIF-α and HIF-β subunits are produced constitutively, but in normoxia the α subunit is degraded by the proteasome in an oxygen-dependent manner. Hydroxylation of two prolines in HIF-α enables HIF-α to bind to the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein (pVHL), which links HIF-α to a ubiquitin ligase complex. The ubiquitin ligase catalyzes polyubiquitinylation of HIF-α, targeting it for degradation by the proteasome. In addition, hydroxylation of an asparagine residue in HIF-α disrupts the interaction between HIF-α and the coactivator p300, through a process independent of proteasomal degradation, which leads to reduced HIF transcriptional activity. Hypoxic conditions prevents hydroxylation of the α subunit, enabling the active HIF transcription complex to form at the HRE (hypoxia response element) associated with HIF-regulated genes.

Because HIF regulates genes that enable cell survival in a hypoxic environment, including those involved in glycolysis, angiogenesis and expression of growth factors, it holds importance in the biology and regulation of tumor growth. The central role of HIF in the activation of angiogenic-related genes makes it a promising target for the treatment of solid tumors particularly since HIF-1α and/or HIF-2α is reported to be overexpressed in the majority of solid tumors85,86. HIF-1α (and sometimes HIF-2α) overexpression in tumors has been found to positively correlate with angiogenesis, aggressiveness, metastasis, and resistance to radiation/chemotherapy and negatively correlate with progression, survival and outcome87,88,89,90,91,92,93 (for an excellent review see reference94).

Anti-Angiogenesis Compounds

Fumagillin and TNP-470

The anti-angiogenic activity of fumagillin was discovered when a dish of cultured endothelial cells was accidentally contaminated with the fungus Aspergillus fumigatus Fresenius, a fumagillin producing organism95. The contaminated endothelial cells stopped proliferating but showed no outward signs of toxicity95. After isolating fumagillin as the source of the activity, a series of synthetic analogues were produced that also inhibited endothelial cell growth and proliferation without cytotoxic effects in vitro, and limited tumor-induced angiogenesis in xenograft models95. The most potent of the analogues, known as TNP-470, was found to be a significantly more potent anti-angiogenic compound than fumagillin in four different angiogenesis assays96. The means by which fumagillin and TNP-470 exert their anti-angiogenic properties are not fully understood. Several mechanism have been proposed, including inhibition of methionine aminopeptidase (MetAP-2)97 through covalent modification of a histidine98 and prevention of endothelial activation of Rac199. TNP-470 also affects cell cycle through activation of p53, leading to an increase in the G1 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21CIP/WAF and subsequent growth arrest100,101.

TNP-470 shows broad spectrum anti-cancer activity in animal models102 and was one of the first anti-angiogenesis drugs to undergo clinical trials (for review see103). In early clinical trials, TNP-470 demonstrated anti-tumor activity as a single agent, causing tumor progression to slow or even regress in squamous cell cancer of the cervix104,105, as well as showing activity in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin106. While TNP-470 appeared promising in terms of anti-cancer activity, it presented several obstacles to further clinical development and use. The primary hurdles included dose-limiting toxicities and a very short plasma half-life107,108. Toxicities seen were mainly neurological including problems with motor coordination, short-term memory and concentration, dizziness, confusion, anxiety, depression107,109. Later studies showed that neurological symptoms could be eliminated by conjugating TNP-470 to a polymer, preventing the drug from penetrating the blood-brain barrier110. However, this formulation still had a short-half life and could not be administered orally110.

To improve upon the short half-life and oral availability, TNP-470 was conjugated to a di-block copolymer, monomethoxy-polyethyleneglycol-polylactic acid (mPEG-PLA). The polymeric drug is amphiphilic causing self-assembly into micelles with the TNP-470 tails in the center102. The micelle formulation improved the properties of TNP-470 in several ways. The micelles protected TNP-470, particularly from the acidic environment of the stomach, making the new formulation, named lodamin, orally available102. Additionally, the micelles increased the half-life, as the micelles hydrolyze over time, allowing slow release of lodamin. This property allowed accumulation of lodamin in tumor tissue (likely due to the permeability of the tumor vasculature), but still prevented penetration of the blood-brain barrier, effectively overcoming several of the major hurdles to clinical use of TNP-470102. One interesting observation was that particularly high concentrations of lodamin accumulated in the liver, so lodamin may prove to be especially effective against primary liver cancer or metastases within the liver102. Pre-clinical results of lodamin are promising thus far and warrant further investigation. Additional studies on the safety of lodamin in non-human primates may lead to clinical trials in the future. Furthermore, second generation conjugated TNP-470 are in pre-clinical development.

Thalidomide

Thalidomide (Thalomid®) was initially marketed as a safe, non-toxic sedative and anti-emetic in the 1950's in Europe, Australia, Asia and South America (but was not FDA-approved in the USA due to safety concerns)111. In countries where it was approved for use, thalidomide became a popular treatment for pregnancy related morning sickness until 1961 when two physicians, William McBride from Australia112 and Widukind Lenz from Germany113 noted the link between severe limb defects and other birth defects in babies whose mothers had taken thalidomide during pregnancy. The drug was rapidly removed from the market in Europe in 1961 and from Canada in 1962 due to the previously unknown teratogenic effects of thalidomide111.

Thalidomide was rediscovered in 1965 as a useful treatment for erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), due to the immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties of thalidomide; however it did not actually obtain FDA approval for ENL until 1998111. The idea of using thalidomide for cancer treatment occurred upon the discovery of its anti-angiogenic properties.

Studies of the effects of thalidomide suggested that the limb defects could be caused by inhibition of blood vessel growth in the limb buds of a developing fetus114. Thalidomide displayed anti-angiogenic properties in a rabbit cornea micropocket model, though interestingly thalidomide did not inhibit angiogenesis in a chicken chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay114. It was proposed that the teratogenic activity of thalidomide may be due to one of the many metabolites of the parent thalidomide model, explaining the lack of activity in the CAM assay114,115. Bauer et al. examined this proposal using liver microsomes co-incubated with thalidomide in angiogenesis assays116. Co-incubation with human or rabbit liver microsomes led to potent anti-angiogenic activity, demonstrating that a metabolite of thalidomide is responsible for the anti-angiogenic activity, and that the metabolite is not produced by rodents116.

While the mechanism of thalidomide (and metabolites) is not fully understood, some properties and activities of thalidomide are beginning to be deciphered. Thalidomide inhibits the synthesis of TNF-α in monocytes, microglia, and Langerhans cells, which provides thalidomide with its anti-inflammatory properties (for review see references111,117). The immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects of thalidomide likely contribute to the anti-angiogenic effects of thalidomide, and add to the anti-cancer activity of thalidomide. Studies of thalidomide in rabbits, an animal species susceptible to thalidomide's teratogenic effects, causes inhibition of mesenchyme proliferation in the developing limb bud of a fetus118, embryonic DNA oxidation and teratogenicity119.

Unfortunately the pre-clinical animal studies of thalidomide that led to widespread use in humans throughout the world used rodents, which are resistant to the teratogenic effects of thalidomide. The human tragedies that resulted from thalidomide highlight the importance of selecting correct animal models, as well as testing in different species when examining new treatments for clinical use119.

Thalidomide analogues were developed with the goal of improving TNF-α inhibition, leading to lenalidomide (CC-5013, Revimid®) and pomalidomide (CC-4047, Actimid®), the latter of which is 50,000-fold more potent than thalidomide at suppressing endotoxin-induced TNF-α secretion in cell models117. Lenalidomide and pomalidomide also lack some of the side-effects seen with thalidomide such as constipation, peripheral neuropathy and the sedative effects111,117. In 2006, lenalidomide was approved by the FDA for use in relapsed multiple myeloma in combination with dexamethasone, while pomalidomide is currently in clinical development120.

Despite the previous damage thalidomide caused (and even, perhaps due to thalidomide's mechanism of action that led to birth defects), thalidomide and analogues are currently in development for anti-angiogenic and anti-cancer use. While the complex metabolism of thalidomide causes many challenges to the development of thalidomide, initial results with analogues appear to indicate that structural alterations can change the side-effect profile, potentially eliminating them, while still maintaining the desired anti-cancer activity and demonstrating promising results in clinical trials.

Inhibitors of Growth Factors, Receptor Tyrosine Kinases and Signaling Pathways

Because growth factors stimulate endothelial cells, leading to angiogenesis, targeting the growth factors, receptors and subsequent signaling cascades make for promising targets in angiogenesis inhibition. The growth factors and receptor tyrosine kinases are particularly attractive targets since it is possible to target them in the extracellular environment, removing drug development hurdles such as permeability of the cellular membrane. Significant progress towards targeting these pathways has been made and a number of drugs have been FDA approved or are in clinical development.

Growth Factor Inhibitors

Bevacizumab (Avastin™) is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to VEGF-A, preventing it from binding to receptors and activating signaling cascades that lead to angiogenesis. Initial proof of concept that targeting VEGF-A could inhibit the growth of tumors (despite having no effect on growth rate of the tumor cells in vitro) was demonstrated in a mouse model in 1993 using a monoclonal antibody against VEGF-A121, leading to the clinical development of bevacizumab.

Initial clinical trials in colorectal cancer tested irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and leucovorin with or without bevacizumab122. The addition of bevacizumab significantly increased progression-free survival (PFS), as well as median overall survival (OS)122, leading to FDA approval of bevacizumab as the first drug developed solely for anti-angiogenesis anti-cancer use in humans.

Anti-cancer activity of bevacizumab across all tumor types has demonstrated some mixed results. Bevacizumab did not provide any benefit to PFS or OS for metastatic breast cancer patients when used in combination with capecitabine123. Further studies in a Phase III trial on previously untreated metastatic breast cancer using paclitaxel with or without bevacizumab showed that the addition of bevacizumab increased PFS (11.8 months versus 5.9 months) and increased overall response rates (36.9% versus 21.2% without bevacizumab)124. However, there was still no significant increase in overall survival, as had been seen previously with colorectal cancer122 and NSCLC125,126. A beneficial response may masked by the lack of biomarker screening in patients in many of the clinical trials, since bevacizumab is specific for VEGF. By screening for tumors that overexpress VEGF and/or are highly dependent on VEGF signaling, the likelihood of a positive response to treatment of bevacizumab would probably be increased. Targeted therapies may prove more effective when patients are screened for markers, ensuring that the proper subset of the population is treated with a particular targeted drug.

Bevacizumab is currently being tested in several hundred clinical trials in a variety of different tumor types127 and as of 2009, bevacizumab is approved for various indications in colorectal cancer, NSCLC, breast cancer, renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and glioblastoma.

Aflibercept (VEGF-trap)

Aflibercept (VEGF-trap, AVE0005) is a soluble fusion protein of the human extracellular domains of the VEGFR-1 and -2 receptors and the Fc portion of human IgG. Aflibercept binds to both VEGF-A and PlGF with a higher affinity than monoclonal antibodies and essentially renders the VEGF-A and PlGF ligands unable to bind and activate cell receptors128. Aflibercept was engineered to optimize pharmacokinetic properties while still maintaining the potent VEGF blocking activity that other anti-VEGF antibodies have demonstrated. In vitro, aflibercept showed significant anti-proliferative activity and completely blocked VEGF-induced VEGFR-2 phosphorylation when added in a 1.5 molar excess of VEGF128. Aflibercept inhibited tumor growth in xenograft models and blocked nearly all tumor-associated angiogenesis, resulting in tumors that appeared nearly avascular128.

Aflibercept is in clinical trials with some early results reported. In Phase II trials as a single agent in ovarian cancer, 41% of patients had stable disease at 14 weeks129. In addition, a reduction of 30% or more in tumor size was seen in 8% of patients129. Another Phase II trial of aflibercept in 33 NSCLC patients, showed two partial responses; interim analysis results are not yet available130. In contrast, a Phase II trial of aflibercept in metastatic breast cancer showed a response rate of 5% and PFS at six months of 10%, rates that did not meet efficacy goals and were decided too low to continue131. Additional clinical trials of aflibercept are ongoing in a variety of cancers including prostate, colorectal, ovarian, thyroid, RCC, and brain cancers.

Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

There are a wide range of receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitors in all stages of development (pre-clinical, clinical and FDA-approved). RTK inhibitors are particularly useful in treating cancer because of the dual roles they inhibit; both oncoprotein signal-transduction and the downstream angiogenic processes are blocked. They also often target more than one type of receptor and affect both endothelial cells and cancer cells because the receptors are expressed on both types of cell3. Since the target kinase specificity between inhibitors can vary, different compounds have shown varying levels of efficacy and activity between cancers, as well as different side effect profiles. Several approaches to targeting the growth factors and receptors have been undertaken; some of these include compounds that bind to the ATP binding site of the receptor tyrosine kinase, blocking receptor activation, or with antibodies that bind to the growth factors or their receptor, preventing binding and subsequent receptor activation

Sunitinib (Sutent®, SU11248) is an orally available compound that inhibits the VEGFR, PDGFR, Flt-3, c-kit, RET and CSF-1R receptor tyrosine kinases (for review see reference132). In a Phase III clinical trial in metastatic RCC patients, sunitinib was compared to interferon-α (IFN-α), with sunitinib providing a statistically significant improvement in both the median PFS (47.3 weeks for sunitinib versus 24.9 weeks for IFN-α) and the objective response rate (24.8% versus 4.9% for IFN-α)133. In addition, the interim analysis of a Phase III trial of sunitinib in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) revealed a significantly longer time to progression (27.3 weeks for sunitinib versus 6.4 weeks for placebo), and at 22 weeks, stable disease was seen in 17.4% of patients versus 1.9% of patients on placebo134,135. A partial response was seen in 6.8% of sunitinib patients versus 0% of patients treated with the placebo134,135. The results from these trials led to FDA approval of sunitinib in 2006 for GIST and advanced metastatic RCC. Further studies and clinical trials are currently being conducted in additional cancers using sunitinib.

Sorafenib (Nexavar®, BAY 43-9006) is an oral inhibitor of the intracellular Raf kinase (B-Raf, C-Raf), therefore targeting the MAPK and Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathways. Sorafenib also inhibits VEGFR (-2 and -3), PDGFR-β and c-kit (for review see reference136). In most tumor cell lines (colon, pancreatic and breast), but not all (NSCLC), sorafenib potently inhibited the Raf kinase, and blocked phosphorylation of ERK 1/2, an indicator of MAPK pathway blockade137. Sorafenib was also shown to possess significant anti-angiogenesis activity in vitro137.

A Phase II trial of sorafenib in advanced RCC showed an increased PFS rate after 12 weeks (50% with sorafenib versus 18% with placebo) and a significantly increased median PFS (23 weeks versus 6 weeks with placebo)138. In a Phase III trial of RCC (769 patients) sorafenib increased median PFS from 12 weeks with placebo to 24 weeks and increased PFS after 12 weeks (79% versus 50% with placebo)139. Sorafenib was subsequently approved by the FDA for RCC in 2005 and unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in 2007.

Semaxanib (SU5416) was the first tyrosine kinase inhibitor tested in humans and is an inhibitor of VEGFR (for review of semaxanib see reference140). Semaxanib was tested in combination with 5-FU/leucovorin compared to 5-FU/leucovorin alone in a Phase III trial against metastatic colorectal cancer (737 patients)141. Addition of semaxanib did not improve clinical outcome and additional toxicities were seen in the semaxanib arm, including an increased risk of hematological and thromboembolic events141. Semaxanib in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine also had unacceptable toxicity associated with it, particularly severe thromboembolic events142, leading to the clinical development of semaxanib to be stopped5.

Erlotinib (Tarceva®, OSI-774) is an oral inhibitor of the EGFR/HER1 receptor tyrosine kinase. Erlotinib is believed to exert anti-cancer activity at least partially through the inhibition of expression of pro-angiogenic factors143. While Phase III clinical trials had some mixed results, with two trials seeing no benefit in treating previously non-treated NSCLC with chemotherapy and erlotinib144,145, one trial in NSCLC that had failed chemotherapy treatment, showed erlotinib provided an increase in PFS (2.2 months versus 1.8 months with placebo), median duration of response (7.9 months versus 3.7 months with placebo), response rate (8.9% versus less than 1% with placebo), and overall survival (6.7 months versus 4.7 months with placebo)146. A Phase III trial of erlotinib in combination with gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer showed significantly improved survival147. The results of these trials led to erlotinib being FDA approved for NSCLC that has failed chemotherapy treatment and for pancreatic cancer in combination with gemcitabine.

Cediranib, pazopanib, vandetanib, lapatinib, and motesanib are examples of additional receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors that are currently in clinical trials for a variety of cancers148 (table 2).

Table 2.

Examples of Kinase Inhibitors (not an exhaustive list)

| Inhibitor | Other names | Inhibits |

|---|---|---|

| Axitinib | AG013736 | VEGFR, PDGFR and c-kit |

| Canertinib | CI-1033 | EGFR, HER-2, HER-3 and HER-4 |

| Cediranib | Recentin™, AZD2171 | VEGFR, PDGFR-β and c-kit |

| Dasatinib | Sprycel, BMS-354825 | Abl, Src, Tec |

| Erlotinib | Tarceva®, OSI-774 | EGFR/HER1 |

| Gefitinib | Iressa™ | EGFR/HER1 |

| Imatinib | Gleevec®, STI571 | Abl, PDGFR and c-kit |

| Lapatinib | Tykerb, GW-572016 | EGFR and HER2 |

| Leflunomide | Arava, SU101 | PDGFR (EGFR, FGFR) |

| Motesanib | AMG 706 | VEGFR, PDGFR and c-kit |

| Neratinib | HKI-272 | EGFR and HER2 |

| Nilotinib | Tasigna | Abl, PDGFR and c-kit |

| Pazopanib | Armala®, GW786034 | VEGFR, PDGFR-α and -β and c-kit |

| Regorafenib | BAY 73-4506 | VEGFR-2 and Tie-2 |

| Semaxinib | SU5416 | VEGFR |

| Sorafenib | Nexavar®, BAY 43-9006 | Raf, VEGFR (-2 and -3), PDGFR-β and c-kit |

| Sunitinib | Sutent®, SU11248 | VEGFR, PDGFR, Flt-3, c-kit, RET and CSF-1R |

| Tandutinab | MLN518, CT53518 | PDGFR, Flt-3 and c-kit |

| Toceranib | ||

| Vandetanib | Zactima™, ZD6474 | VEGFR-2, PDGFR-β, EGFR and RET |

| Vatalanib | PTK787 | VEGFR, PDGFR-β and c-kit |

Imatinib (Gleevec®, STI571) inhibits the cytoplasmic and nuclear protein tyrosine kinase, Abl, as well as the receptor tyrosine kinases PDGFR and c-kit149. Imatinib was the first commercially available small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor and has been used extensively in the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) because the molecular pathogenesis of CML involves the Bcr-Abl protein and deregulated tyrosine kinase activity149. Imatinib demonstrates anti-angiogenesis activity in vitro, which is thought to occur through inhibition of PDGFR150,151.

Monoclonal Antibodies Directed at EGFR

Cetuximab (Erbitux®) and panitumumab (Vectibix, ABX-EGF) are indirect receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors, using a different approach than the above small molecule inhibitors. Cetuximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody that binds to the inactive form of EGFR on the extracellular domain101. Cetuximab essentially prevents the ligand from being able to bind to the receptor and therefore any downstream signaling activation152. It received accelerated FDA approval in 2004 for use in EGFR-expressing metastatic colorectal cancer in combination with irinotecan or as a single agent for irinotecan-intolerant patients, after cetuximab showed activity in clinical trials as a single agent and even more activity when used in combination with irinotecan153,154,155. Cetuximab was subsequently tested in combination with radiotherapy for the treatment of unresectable head and neck SCC and showed that the addition of cetuximab to radiotherapy significantly increased median survival compared to radiotherapy alone156, leading to additional FDA approval for this use. As for the anti-angiogenic activity of cetuximab, studies have shown that EGF/EGFR inhibitors appear cause a reduction in the synthesis of pro-angiogenic cytokines, rather than a direct inhibition of angiogenesis55. Panitumumab is also a monoclonal antibody that binds to EGFR, inhibiting phosphorylation and activation of EGFR associated kinases151.

PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway Inhibitors

PI3K signaling contributes to many cell processes, including angiogenesis, cell proliferation, survival and motility, and is initiated by activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (for review see reference23,24). Upregulation of the PI3K pathway can increase angiogenesis through multiple pathways, including increasing the levels of HIF-1α under normoxic conditions12,13,19,14,15,18,20.

Initial evidence that PI3K and AKT were involved in the regulation of angiogenesis in vivo was obtained when constitutively active PI3K and AKT were shown to induce angiogenesis and increase levels of VEGF12. Cancer genome studies have highlighted the importance of this, demonstrating that components of the PI3K pathway are often mutated in human cancers, increasing the likelihood of inhibitors of this pathway demonstrating efficacy in the clinic24.

Inhibitors of the PI3K pathway have been found to decrease tumor angiogenesis and demonstrate HIF inhibition, including LY294002 and wortmannin, two compounds that directly inhibit members of the PI3K family15,13,12,14,11,20. Both LY294002 and wortmannin showed unacceptable levels of toxicity in animals and therefore were not developed clinically; however a wortmannin analogue, PX-866, and a conjugate version of LY294002, are both currently being tested in Phase I trials24. 9-β-D-arabinofuranosyl-2-fluoroadenine (FARA-A) is a nucleoside analogue that causes DNA damage in S-phase cells and has been found to inhibit AKT, thereby inhibiting the expression of HIF-1α and VEGF157. Perifosine is a lipid-based phosphatidylinositol analogue that inhibits AKT by preventing translocation of AKT to the cell membrane24. Perifosine is currently in clinical trials for several different cancers. Rapamycin (sirolimus) acts as an inhibitor of mTOR and was initially used as an immunosuppressive agent25. Rapamycin and analogues including temsirolimus (CCI-779), and everolimus (afinitor, RAD001), block tumor angiogenesis in vivo, in addition to inhibiting tumor growth19,158,159,160,161. The blocked angiogenesis is believed to be due at least partially to the inhibition of HIF-1α caused by the inhibition of mTOR19,158,159,160. While rapamycin inhibits HIF-1α in vitro, it is unknown to what degree the decrease in HIF-1α actually plays in the anti-tumor activity, since the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway plays a role in many cell processes and the anti-tumor activity may stem from acting upon multiple downstream targets.

Clinical trials of temsirolimus and everolimus as single agents improved survival in patients with advanced RCC, leading to FDA approval for this indication. Results of activity in other tumors have initially indicated mixed results and are being further tested25,24.

MAPK- Farnesyltransferase Rho and Ras Inhibitors

The MAPK signaling pathway is another pathway that can lead to increased angiogenesis and increased levels of HIF-1α, making it a logical anti-angiogenesis target. One approach has been to inhibit Ras and Rho, activators of the MAPK pathway. During Ras activation, a farnesyl group is transferred onto a cysteine residue in the C-terminal end of Ras, enabling Ras to interact with intracellular membranes via the farnesyl group26. Without farnesylation, Ras can no longer interact with regulatory and effector molecules in the cell membrane and no MAPK pathway activation occurs. Ras is also involved in stabilizing HIF-1α and targeting Ras has been shown to destabilize HIF-1α and decrease HIF transcriptional activity15,20. Two farnesyltransferase inhibitors are tipifarnib (zarnestra®, R115777)162 and lonafarnib (Sarasar®, SCH66336)163. Tipifarnib has been the most studied farnesyltransferase inhibitor thus far, with anti-angiogenic, anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic activity in preclinical studies164,165. However, clinical trials of tipifarnib in multiple cancers failed to show significant anti-cancer activity (for review see reference162). It remains to be seen whether inhibition of farnesylation may or may not be an effective anti-cancer strategy. Sorafenib, mentioned previously under tyrosine kinase inhibitors, also acts on the MAPK pathway through inhibition of Raf136.

Interferon-α

Interferon-α (IFN-α) was first discovered to have anti-endothelial activity in 1980, when experiments showed that it inhibited the motility of endothelial cells in vitro166 and inhibited angiogenesis in vivo167,168. Low doses of IFN-α have been shown to downregulate FGF expression in cancer cells169, and is probably one of the mechanisms behind the anti-angiogenic effects of IFN-α. In 1989, IFN-α was first used in humans to treat a hemangioendothelioma. After a low-dose daily treatment for seven months, complete regression of lesions and symptoms occurred170. These results led to the successful treatment of infant haemangiomas with IFN-α171, in addition to successful treatment of angioblastomas and giant cell tumors172,173,174.

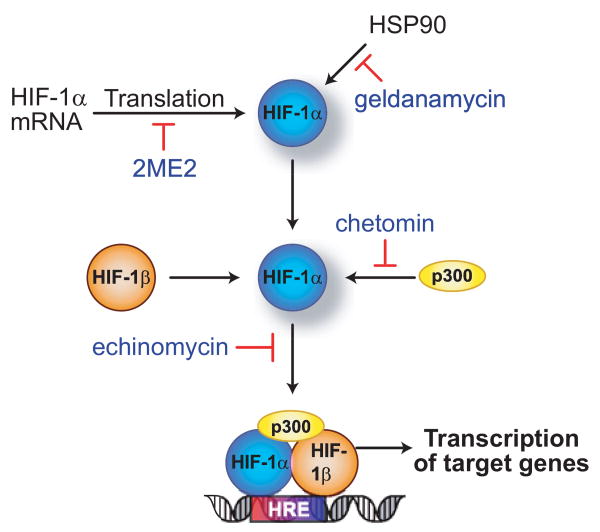

2-Methoxyestradiol (2ME2)

2-Methoxyestradiol (2ME2, Panzem®) is a human metabolite of estradiol that inhibits tubulin polymerization, destabilizing the microtubules, and causing cell cycle arrest175. 2ME2 has also been found to decrease HIF-1α protein levels by acting at the translational level without affecting rates of HIF-1α gene transcription or HIF-1α proteasomal degradation through a mechanism dependent on the microtubule disrupting properties of 2ME2175. 2ME2 possesses potent anti-angiogenic and pro-apoptotic properties and inhibits cell proliferation and migration both in vitro and in vivo176. The anti-angiogenic properties of 2ME2 appear to come from both direct inhibition of endothelial cells, and inhibition of HIF-1α175. In clinical trials, little anti-tumor activity was seen in breast and prostate cancers, which may be due to the short half-life and poor bioavailability of 2ME2177. Re-formulation has improved upon bioavailability, though the half-life is still sub-optimal177. Development of analogues with improved properties may increase the efficacy and potential clinical use for 2ME2. A more thorough understanding of the targets which 2ME2 acts upon and the relationship between microtubules and HIF-1α may provide new therapeutic avenues.

Hypoxia Inducible Factor Pathways and Binding Partners

The central role of HIF in the transcriptional activation of genes under hypoxic conditions, including those involved in angiogenesis and cell proliferation, makes it a promising target for cancer treatment. There is good evidence that treatments targeting HIF, or components of the HIF regulatory pathway will result in a physiological effect in humans178. Work on some of the different approaches focusing directly on HIF and its binding partners is discussed in the following section (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Examples of inhibitors known to act on HIF and/or HIF regulatory pathways are shown.

Preventing DNA Target Sequence Binding

One method of preventing transcriptional activation of HIF (and other transcription factors) is to block binding to its target DNA site, the HRE, inhibiting gene expression of VEGFA and other HIF regulated genes. The natural product echinomycin, has been found to bind a region of the HRE sequence (5′- ACGT -3′), which is also shared with the consensus sequence of c-Myc, another cancer-related transcription factor179. Echinomycin inhibited HIF transcriptional activity and VEGF expression in tumor cells in vitro, without inhibiting other tested transcription factors179. However, clinical trials using echinomycin produced disappointing results180, which may be due in part to the unclear selectivity and specificity of echinomycin, which binds only a short region of DNA. Despite the lack of clinical success seen with echinomycin, inhibition of the HIF-HRE complex still holds promise as a selective HIF inhibitor.

In an effort to generate a more specific HRE binding inhibitor, a series of polyamides were designed to specifically bind the VEGFA promoter sequence 5′- WTWCGW -3′, which did lead to a decrease in VEGF-A mRNA and protein levels in vitro181. Another model utilized hairpin polyamides designed to bind HRE sequences182. While the hairpin polyamides did not have as strong of an effect on HIF-regulated genes as a HIF-1α siRNA model, the results did suggest that polyamides could potentially be designed to affect a select subset of target genes by targeting particular HREs182 and further validating HRE sites as a molecular target for pharmacological manipulation.

Preventing Cofactor Binding

Another way of blocking HIF activation is preventing HIF from binding to essential transcriptional coactivators. The interaction between the HIF-1α CTAD domain and the CH1 domain of the coactivator p300 has been demonstrated to be a potential drug target using polypeptides corresponding to the CH1 or the CTAD domain, which led to attenuation of HIF transcriptional activity in cell-based models and anti-tumor activity in xenograft models183.

A small molecule, chetomin, found in a high-throughput screen, blocked binding of p300 to either HIF-1α or HIF-2α in both in vitro and in vivo assays184. In xenograft models, systemic administration of chetomin attenuated HIF-1-mediated gene expression, and caused a significant reduction in tumor size184. While high levels of necrosis in tumor tissues were observed, repeated injections led to localized toxicity and coagulative necrosis at sites of tail vein injection. Unfortunately, due to the toxicity, chetomin is unlikely to be pursued as a chemotherapeutic drug, but it did prove that inhibition of HIF:p300 had anti-tumor effects, establishing this as a potential drug target.

Recent structure-activity studies on chetomin led a series of analogues that have shown some activity in vitro185. Chetomin and analogues were found to disrupt the structure of the CH1 domain of p300, to which the HIF-α subunit binds, by chelating structural zincs bound to p300. The unstructured p300 can then no longer bind HIF-α, preventing transcriptional activation of HIF185. Further studies on zinc chelation of p300 and downstream effects on HIF transcriptional activity could utilized for drug development of this target.

Inhibition of HSP90

The chaperone HSP90 (heat shock protein 90) possesses a wide range of functions, assisting in folding and stabilizing many cellular proteins186. Client proteins of HSP90 include oncoproteins and/or angiogenic related proteins, for example, HIF-1α, AKT and mutant EGFR186, making HSP90 a regulatory component of many oncogenic processes. In addition, HSP90 is often overexpressed in cancer cells, can contribute to malignant transformation of cells and has been associated with decreased survival in breast cancer187. It was initially thought that inhibition of HSP90 may not demonstrate selectivity for cancerous cells because there are high levels of HSP90 present in nearly all tissues, and HSP90 interacts with a large number of important cellular proteins in healthy cells; however, experimental evidence revealed that cancer cells were actually more sensitive to HSP90 inhibitors than healthy cells186.

In vitro evidence has shown that inhibitors of HSP90, such as geldanamycin (GA) and its analogues 17-AAG (17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin) and 17-DMAG (17-dimethylaminomethylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin), do act on client proteins, for example GA and 17-AAG promote HIF-α degradation188. By inhibiting HSP90 from binding to HIF-1α, the protein RACK1 is able to bind HIF-1α, recruiting a ubiquitin ligase complex, inducing ubiquitination, and leading to proteasomal degradation189. 17-AAG was the first inhibitor to enter the clinic and showed limited success; subsequent alterations to the formulation and delivery have improved upon the efficacy186. Clinical trials of several HSP90 inhibitors are ongoing. While 17-DMAG was halted for clinical development in 2008 due to unfavorable toxicity, 17-AAG is currently in clinical trials for anti-cancer uses and the effect on HIF-1α and angiogenesis is of interest190

Thioredoxin Inhibitors

The thioredoxins (Trx) are redox proteins that function to reduce oxidized cysteines in proteins through an NADPH-dependent reaction. One member, thioredoxin-1 (Trx-1) is overexpressed in many human tumors and has been associated with decreased patient survival191. Trx-1 participates in the regulation of transcription factors, including HIF-1α192. Overexpression of Trx-1 has been shown to increase levels of HIF-1α protein and VEGF expression in vitro, and increase angiogenesis in vivo, making it an attractive target for HIF and angiogenesis inhibition193. Inhibition of Trx-1 by PX-12 and pleurotin prevents accumulation of HIF-1α protein in hypoxic conditions, as well as decreases HIF-regulated gene expression in vitro and in vivo194. PX-12 became the first thioredoxin-1 inhibitor to enter a Phase I trial of 38 patients with various types of solid tumors. PX-12 showed some preliminary anti-tumor activity in the Phase I trial195, and as of mid-2009, PX-12 is currently being tested in two Phase II trials for advanced/metastatic cancer and advanced pancreatic cancer.

Known and Potential Side Effects from Inhibition of Angiogenesis

While many of the molecular targets proposed for inhibition of angiogenesis appear promising, particularly through targeting HIF and related pathways, caution should always be employed when applying findings from in vitro studies to clinical applications. As with most studies using isolated systems and molecular targets, many of the results obtained in preclinical studies have yet to be verified as relevant in a clinical setting. Even the importance of molecular targets, such as HIF, are still unknown in a clinical setting and many of the pre-clinical studies have found conflicting results. For example, studies using embryonic stem cell tumors found that inhibition of HIF increased tumor growth196,197, and that activation of HIF led to a slower growth rate than the wildtype cells198, indicating that the biology of HIF is still not completely understood. Caution should be exercised when drawing conclusions as to the role of the HIF system in cancer from results obtained using a limited number of cell types. Similar conclusions apply to other molecular targets in angiogenesis, particularly those that have not yet been targeted in humans, as there is still a significant knowledge gap in our understanding between pre-clinical and clinical studies.

In addition, as the use of angiogenesis inhibitors like bevacizumab becomes widespread, the potential side effects that occur in short- or long-term use of angiogenesis inhibitors are becoming apparent. Some of these side effects include gastrointestinal perforations, impaired wound healing, bleeding, hypertension, proteinuria and thrombosis (for review see references199,200,201). Many of the side effects are actually due to the direct effects of the drugs; cardiovascular complications are thought to be caused by direct effects of angiogenesis inhibitors on the non-tumor-associated endothelial cells200. The likelihood for these occurrences has thus far, been unpredictable and further studies are needed to measure the risk for patients, understand the cause for complications and find prophylactic measures to minimize risk. The effects of long-term administration of angiogenesis inhibitors are not fully known, as most long-term studies have not yet been conducted due to the recent development of these drugs101.

It has also been found that most tumors develop mechanisms of resistance to anti-angiogenic agents202, and may be a potential consequence of long-term administration of anti-angiogenesis inhibitors. Because multiple signaling pathways are involved in angiogenesis and more than one pathway is often dysregulated in human tumors, there is a certain level of signaling redundancy, and blocking a single pathway may not be highly effective and/or can lead to resistance when the tumor cells develop other angiogenesis mechanisms (for a review of other mechanisms of resistance see Eikesdal et al.202). By targeting multiple pathways, resistance may be able to be overcome or delayed, making combination drug therapies important in the design of future clinical trials.

Conclusion

The complex molecular pathways that govern tumor angiogenesis are logical targets for pharmacological manipulation given the important role they play in the growth and development of cancers. Initial trials of putative anti-angiogenesis inhibitors have shown some promise in cancer, although this has not always translated to the clinic. A lack of validated biomarkers and patient screening restricts our ability to tailor specific drugs to patient cohorts, and might be seen as one of the largest barriers to success in angiogenesis inhibition. As cancer pharmacology moves away from cytotoxic to so-called molecular targeted drugs that are expected to have minimal side effects and toxicity, predictive biomarkers could be used to screen for patients likely to demonstrate a clinical response. Biomarkers also need to be validated for use as objective response measurements, since anti-angiogenic monotherapies may only act as cytostatic agents, making objective response measurements like tumor shrinkage, less useful for determining the efficacy of a drug. The long time period required for an observable response also demonstrates the need for a rapid biomarker so that response to a treatment can be measured. While some clinical trials have shown that particular surrogate biomarkers of angiogenesis, like circulating VEGF and microvessel density, have value as prognostic markers, more validated biomarkers need to be found so that anti-angiogenic agents can be properly used and evaluated in the clinic (for review see reference203,204).

The end goals of anti-angiogenesis inhibitors also need to be determined. It is still not understood if angiogenesis inhibitors will eliminate or shrink tumors or simply inhibit further growth and spread. If angiogenesis inhibitors are used as a cytostatic agent, then further studies are needed to examine the effect of vessel normalization, whereby the tumor vessels become more organized and blood flow is improved and if improved tumor delivery of chemotherapeutics could be achieved. This means more studies using combination therapies with angiogenesis inhibitors, and determining whether angiogenesis inhibitors are more effective in combination with chemotherapy or as single agents. In vitro studies have found that combination with traditional chemotherapies and/or radiation increases the anti-tumor efficacy of kinase inhibitors149 and this seems to be true with many of the anti-angiogenesis inhibitors205. It is also thought that combination therapies could be used to provide maximum anti-tumor effect and minimal side effects if a lower dose of each drug were to be used. Treatments could be tailored to target the specific altered pathways in a tumor with a combination of drugs to minimize resistance and provide a more effective combined treatment. Future clinical studies may provide the information needed to find the best combination of treatments for maximum anti-cancer effect and minimal side effects.

The past decade has led to major advances in the understanding the molecular pathways involved in tumor angiogenesis. This basic research has led to the identification of new targets associated with angiogenesis, leading to the development of an extensive number of pre-clinical anti-angiogenesis agents. Ongoing studies of different approaches are evaluating some of the molecular targets and agents, with some even in clinical trials, and data regarding efficacy and safety is currently emerging.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: None

References

- 1.Folkman J. Tumor Angiogenesis: Therapeutic Implications. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1182–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerbel RS. Inhibition of Tumor Angiogenesis As a Strategy to Circumvent Acquired Resistance to Anti-Cancer Therapeutic Agents. Bioessays. 1991;13(1):31–36. doi: 10.1002/bies.950130106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staton CA, Brown NJ, Reed MW. Current Status and Future Prospects for Anti-Angiogenic Therapies in Cancer. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2009;4(9):961–979. doi: 10.1517/17460440903196737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergers G, Benjamin LE. Tumorigenesis and the Angiogenic Switch. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(6):401–410. doi: 10.1038/nrc1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gasparini G, Longo R, Toi M, Ferrara N. Angiogenic Inhibitors: a New Therapeutic Strategy in Oncology. Nat Clin Prac Oncol. 2005;2(11):562–577. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerbel RS, Viloria-Petit A, Klement G, Rak J. ‘Accidental’ Anti-Angiogenic Drugs: Anti-Oncogene Directed Signal Transduction Inhibitors and Conventional Chemotherapeutic Agents As Examples. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36(10):1248–1257. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The Hallmarks of Cancer. Cell. 2000;100(1):57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in Health and Disease. Nat Med. 2003;9(6):653–660. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Regulation of Angiogenesis by Hypoxia: Role of the HIF System. Nat Med. 2003;9(6):677–684. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hellwig-Burgel T, Rutkowski K, Metzen E, Fandrey J, Jelkmann W. Interleukin-1beta and Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Stimulate DNA Binding of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1. Blood. 1999;94(5):1561–1567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stiehl DP, Jelkmann W, Wenger RH, Hellwig-Burgel T. Normoxic Induction of the Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1alpha by Insulin and Interleukin-1beta Involves the Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Pathway. FEBS Lett. 2002;512(1-3):157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang BH, Jiang G, Zheng JZ, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Signaling Controls Levels of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1. Cell Growth Differ. 2001;12(7):363–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhong H, Chiles K, Feldser D, et al. Modulation of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1α Expression by the Epidermal Growth Factor/Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/PTEN/AKT/FRAP Pathway in Human Prostate Cancer Cells: Implications for Tumor Angiogenesis and Therapeutics. Cancer Res. 2000;60(6):1541–1545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukuda R, Hirota K, Fan F, et al. Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 Induces Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-Mediated Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Expression, Which Is Dependent on MAP Kinase and Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Signaling in Colon Cancer Cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(41):38205–38211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen C, Pore N, Behrooz A, Ismail-Beigi F, Maity A. Regulation of Glut1 MRNA by Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1. Interaction Between H-Ras and Hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(12):9519–9525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010144200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rak J, Mitsuhashi Y, Bayko L, et al. Mutant Ras Oncogenes Upregulate VEGF/VPF Expression: Implications for Induction and Inhibition of Tumor Angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 1995;55(20):4575–4580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang BH, Agani F, Passaniti A, Semenza GL. V-SRC Induces Expression of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 (HIF-1) and Transcription of Genes Encoding Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Enolase 1: Involvement of HIF-1 in Tumor Progression. Cancer Res. 1997;57(23):5328–5335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laughner E, Taghavi P, Chiles K, Mahon PC, Semenza GL. HER2 (Neu) Signaling Increases the Rate of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1α (HIF-1α) Synthesis: Novel Mechanism for HIF-1-Mediated Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(12):3995–4004. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.12.3995-4004.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Land SC, Tee AR. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1α Is Regulated by the Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (MTOR) Via an MTOR Signaling Motif. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(28):20534–20543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611782200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blancher C, Moore JW, Robertson N, Harris AL. Effects of Ras and Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) Gene Mutations on Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF)-1α, HIF-2α, and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Expression and Their Regulation by the Phosphatidylinositol 3′-Kinase/Akt Signaling Pathway. Cancer Res. 2001;61(19):7349–7355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madhusudan S, Ganesan TS. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. Clin Biochem. 2004;37(7):618–635. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krause DS, Van Etten RA. Tyrosine Kinases As Targets for Cancer Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(2):172–187. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra044389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engelman JA. Targeting PI3K Signalling in Cancer: Opportunities, Challenges and Limitations. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(8):550–562. doi: 10.1038/nrc2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu P, Cheng H, Roberts TM, Zhao JJ. Targeting the Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Pathway in Cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8(8):627–644. doi: 10.1038/nrd2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faivre S, Kroemer G, Raymond E. Current Development of MTOR Inhibitors As Anticancer Agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5(8):671–688. doi: 10.1038/nrd2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Downward J. Targeting RAS Signalling Pathways in Cancer Therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(1):11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grothey A, Galanis E. Targeting Angiogenesis: Progress With Anti-VEGF Treatment With Large Molecules. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6(9):507–518. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrara N. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor. Arterioscler, Thromb, and Vasc Biol. 2009;29(6):789–791. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferrara N. VEGF and the Quest for Tumour Angiogenesis Factors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(10):795–803. doi: 10.1038/nrc909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The Biology of VEGF and Its Receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9(6):669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Senger DR, Galli SJ, Dvorak AM, et al. Tumor Cells Secrete a Vascular Permeability Factor That Promotes Accumulation of Ascites Fluid. Science. 1983;219(4587):983–985. doi: 10.1126/science.6823562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrara N, Henzel WJ. Pituitary Follicular Cells Secrete a Novel Heparin-Binding Growth Factor Specific for Vascular Endothelial Cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;161(2):851–858. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92678-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]