Abstract

Objectives

Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) have anti-inflammatory effects and are required for normal endothelial function. The soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) metabolizes EETs to their less active diols. We hypothesized that knockout and inhibition of sEH prevents neo-intima formation in hyperlipidemic ApoE−/− mice.

Methods and Results

Inhibition of sEH by 12-(3-adamantan-1-yl-ureido) dodecanoic acid (AUDA) or knockout of the enzyme significantly increased plasma EET levels. sEH activity was detectable in femoral and carotid arteries. sEH knockout or inhibition resulted in a significant reduction of neo-intima formation in the femoral artery cuff model but not following carotid artery ligation. Although macrophage infiltration occurred abundantly at the site of cuff placement in both sEH+/+ and sEH−/−, the expression of pro-inflammatory genes was significantly reduced in femoral arteries from sEH−/−-mice. Moreover, an in vivo-BrdU-assay revealed that SMC-proliferation at the site of cuff placement was attenuated in sEH knockout and sEH inhibitor treated animals.

Conclusions

These observations suggest that inhibition of sEH prevents vascular remodelling in an inflammatory model but not in a blood-flow dependent model of neo-intima formation.

Keywords: Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, lipid mediators, neo-intima, migration, smooth muscle cells

Introduction

Neo-intima formation is an important clinical problem contributing to vaso-occlusive diseases such as restenosis after coronary angioplasty or atherosclerosis. The process is complex and at least in rodents involves proliferation of smooth muscle cells (SMCs) in response to growth factors, like PDGF, migration of SMCs into the subendothelial layer 1 as well as recruitment of monocytes and transdifferentiation of circulating progenitor cells at the site of the lesion 2. A multitude of systemic and local factors modulate these events. Mechanical injury, inflammation, oxidative stress 3 and hyperlipidemia promote neo-intima formation, whereas nitric oxide (NO), generated either by endothelial or inducible NO synthases attenuates neo-intima formation 4.

Several different models of neo-intima development can be studied in rodents. In almost every model, hyperlipidemia, induced by fat feeding or genetic deletion of the LDL receptor or apolipoproteins is a prerequisite for neo-intima formation which is then combined with a second stimulus 5. Such a second stimulus is usually an alteration in blood flow and subsequent changes in local endothelial NO production as it occurs in the carotid artery ligation model 6, mechanical injury and endothelial denudation as in the oversized balloon model or vascular irritation induced by a foreign body, e.g. in the femoral artery cuff model 4. Although all of these interventions promote neo-intima formation, the degree of inflammation and the contribution of NO to the process vary considerably. In general, the femoral artery cuff model is considered a “more inflammatory” than the carotid ligation model, the latter being dominated by NO withdrawal.

Nitric oxide, however, is not the only “vasoprotective” endothelial autacoid. Prostacyclin and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) also contribute to the anti-atherosclerotic properties of the endothelium. Indeed, EETs, which are derived from arachidonic acid by epoxygenation through cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYPs), mediate endothelium-dependent vasodilation, promote angiogenesis and have anti-inflammatory properties 7. The availability of EETs is primarily limited by the soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH), which metabolizes EETs to their corresponding dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids (DHETs). DHETs show equivalent or reduced biological activity but are all more hydrophilic and easily excreted 8. SEH inhibition lowers blood pressure in different models of hypertension in rodents 9;10. Moreover, these compounds attenuate the inflammatory response in models of endotoxemia and acute lung injury as well as ischemic injury in stroke models in rats.

The role of vascular-derived EETs in the process of neo-intima formation is unknown and we hypothesized that increasing EET levels by inhibiting the sEH should attenuate neo-intima formation in hyperlipidemic ApoE−/− mice following placement of a femoral artery cuff and carotid artery ligation. The role of sEH was studied by generating sEH-ApoE double knockout mice and by the treatment with the sEH inhibitor 12-(3-adamantan-1-yl-ureido)-dodecanoic acid (AUDA).

Materials and methods

An extended version of the materials and methods section can be found at www.ahajournals.org

Animal models

The experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines on the Use of Laboratory Animals. Both, the University Animal Care Committee and the Federal Authorities for Animal Research of the Regierungspräsidium Darmstadt (Hessen, Germany) approved the study protocol. C57/BL6-ApoE−/− breeding pairs (ApoE−/−) were purchased from Charles Rivers (Deisenhofen, Germany). C57/BL6-sEH−/− mice (F5, sEH−/−) were kindly supplied by F. Gonzalez (NIH, Bethesda, MD) 11 and crossed with ApoE−/− mice to obtain ApoE−/− × sEH−/− animals. ApoE−/− × sEH−/− were backcrossed more than 7 times to obtain ApoE−/− × sEH+/+. For the sake of readability, ApoE−/− × sEH+/+ are denominated as “ApoE−/−“. The sEH inhibitor 12-(3-adamantan-1-yl-ureido)-dodecanoic acid (AUDA, final concentration 100 mg/l) 12 was administered to the animals via drinking water. Neo-intima formation and accelerated atherosclerosis was induced by means of vascular injury through cuff placement around the femoral artery of mice or left common carotid artery ligation as described previously 4-6. After 2 and 4 weeks, respectively, vessels were perfusion fixed, sectioned and analyzed by planimetry. In vivo cell proliferation was determined by BrdU incorporation.

sEH and EET detection

sEH protein was detected by Western blot analysis whereas activity was determined by the conversion of 14,15-EET to 14,15-DHET. EETs and DHETs were measured by LC-MSMS as described previously 13.

Data and statistical analysis

All values are mean SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), unpaired t-test and Mann-Whitney test. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Loss of sEH activity attenuates neo-intima formation in the femoral artery cuff model

Two weeks after cuff placement, a marked neo-intima had developed in the femoral artery of ApoE−/− mice. In animals with genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of the sEH the intima/media ratio was approximately 50% lower than in control animals (Fig. 1). The outer vessel diameter as a parameter of inward or outward remodelling was however identical in all groups, demonstrating that lack of sEH activity leads to an attenuation of neo-intima formation in the femoral cuff model in ApoE−/− mice.

Figure 1.

Neo-intima formation in femoral artery cuff model. Representative sections and statistical analysis from ApoE−/− and ApoE−/− × sEH−/− mice (top) and from ApoE−/− mice treated with solvent or AUDA (bottom) two weeks after cuff placement. Mean ± SEM, n=9-13, *p<0.05. Scale bars=100μm.

sEH knockout has no effect on neo-intima formation following carotid artery ligation

In contrast to the data obtained in the femoral artery cuff model, genetic deletion of the sEH had no effect on neo-intima formation after carotid artery ligation. In ligated vessels, there was no difference in the intima-media ratio and in the constrictive remodelling between ApoE−/− and ApoE−/− × sEH−/− mice (Fig. 2). Given this negative result, the effect of sEH inhibition on neo-intima formation in this model was not tested by additional animal experiments.

Figure 2.

Neo-intima formation in carotid artery ligation model. Representative sections of the ligated left side (top) and statistical analysis (bottom) from ligated and non-ligated arteries of ApoE−/− and ApoE−/− × sEH−/− mice 4 weeks after surgery. Mean ± SEM, n=8-9, p=not significant. Scale bars=100μm.

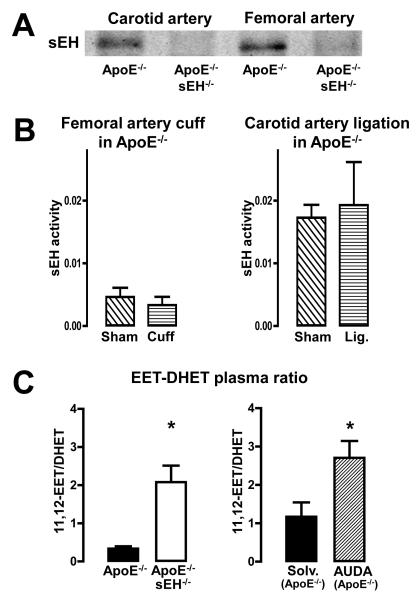

sEH is expressed in the vascular wall of murine carotid and femoral arteries

SEH protein expression was detectable in femoral and carotid arteries of ApoE−/− but not in vessels of ApoE−/− × sEH−/− mice (Fig. 3A). Neither the femoral artery cuff nor the carotid artery ligation had a detectable effect on local sEH activity in ApoE−/− mice (Fig. 3B). In order to demonstrate the impact of the sEH on plasma EET and DHET levels, the four EET and DHET regioisomers were determined (see supplementary figure 1). The ratios of 11,12 EET and 14,15 EET to their corresponding DHETs were significantly increased in ApoE−/− × sEH−/− as compared to ApoE−/− mice (Fig 3C and supplementary figure 1). The sEH-inhibitor AUDA increased the EET-DHET ratio in ApoE−/− mice (Fig 3C and supplementary figure 1), too. These data demonstrate that lack of sEH activity acutely as well as chronically increases the EET to DHET ratio systemically and that there is no local loss of sEH activity in both models which were used in this study.

Figure 3.

sEH and plasma EET concentrations. (A) Representative Western blots for sEH in vascular extracts from ApoE−/− and ApoE−/− × sEH−/− mice. (B) sEH activity (unit: ng14,15-DHET/μg protein/min) in vascular extracts from ApoE−/− mice subjected to sham operation, cuff placement or carotid ligation. n=6, p=not significant. (C) Plasma 11,12-EET-11,12-DHET level ratio from ApoE−/− and ApoE−/− × sEH−/− mice (left) and from ApoE−/− treated with solvent or AUDA (right). n=9-10, *p<0.05.

Loss of sEH activity attenuates SMC proliferation in the femoral artery cuff model

Neointima formation is at least in part a consequence of local proliferation and migration of SMCs. Indeed, immuno-histology of operated femoral arteries revealed that the neo-intima in the cuff model mainly consists of smooth α-actin immuno-positive cells, covered by an intact endothelium, as determined by PECAM-1 staining (Fig. 4A). Macrophages or endothelial cells were almost absent in the neo-intima (Fig. 4A). BrdU labelling showed a significant increase of SMC proliferation in response to femoral artery cuff placement and carotid artery ligation (Fig. 4B, C, D). SMC proliferation in response to cuff placement was significantly attenuated in the femoral of ApoE−/− mice treated with the sEH inhibitors as compared to solvent treated animals (Fig. 4B). Moreover, SMC proliferation was also significantly lower in the cuffed region of femoral arteries of ApoE−/− × sEH−/− mice as compared to ApoE−/− animals (Fig. 4C). In line with the data on neo-intima formation, SMC proliferation in ligated carotid arteries was not affected by genetic deletion of the sEH (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Vessel composition and SMC proliferation. (A) Left panel: Representative section of the femoral artery of an ApoE−/− mouse after cuff placement. PECAM-1 staining was used to identify endothelial cells. PECAM-1 staining also detects macrophages in the adventitia (+: vascular lumen, #: neo-intima, §: medial layer, *: perivascular area). Right panel: Representative image of BrdU incorporation (red) 14 days after operation in a femoral artery subjected to cuff placement. The colour of the label corresponds to the stain indicated. Scale bar= 100μm. (B) BrdU incorporation (mean BrdU immuno-positive cells / orthogonal section) of AUDA treated mice in comparison to solvent treated animals 14 days after femoral artery cuff operation (n=4-7, *p<0.05), (C) of ApoE−/− and ApoE−/− × sEH−/− 14 days after femoral artery cuff placement (n=6-7, *p<0.05) and (D) of ApoE−/− and ApoE−/− × sEH−/− 28 days after carotid artery ligation (n=6, *p<0.05).

Genetic deletion of the sEH attenuates the inflammatory response in the femoral artery cuff model

As also obvious from the H&E staining in Fig. 1 & 2, the femoral artery cuff model, but not the carotid artery ligation model presents with a marked adventitial inflammatory infiltrate (Fig 5A). As EETs have anti-inflammatory effects, we concentrated on this aspect in the femoral artery model as a potential explanation for the anti-proliferative effect of sEH inhibition. As determined by area coverage, the adventitial macrophage infiltrate was similar in ApoE−/− and ApoE−/− × sEH−/− mice. Also sEH inhibitor treatment had no significant effect on macrophage accumulation. In contrast, the sEH controlled the expression of some markers of inflammation: Gro-β and COX2 mRNA was significantly lower and there was a trend towards a reduced CTGF mRNA expression in sEH−/− × ApoE−/− as compared to ApoE−/− mice (Fig. 5B). No difference between ApoE−/− and ApoE−/− × sEH−/− was observed for TNF-α (2.8±0.3 vs. 2.5±0.5), Gro-α (7.0±1.2 vs. 5.8±1.0) and MCP-1 expression (1.9 ± 0.1 vs. 1.7 ± 0.2). Moreover, no differences in mRNA expression were observed between the groups in the carotid artery ligation model (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Perivascular inflammation. (A) Left panel: Representative image of perivascular macrophage infiltration (F4/80 staining) of a femoral artery from an ApoE−/− mouse 14 days after cuff placement. The colour of the label corresponds to the stain used. +: endovascular lumen; *: free space after cuff removal. Scale bar= 40μm. Right panel: F4/80 immuno-positive perivascular area fraction in ApoE−/− and ApoE−/− × sEH−/− mice 14 days after cuff placement. (B) mRNA expression of the genes indicated as relative gene expression in the femoral arteries from ApoE−/− and ApoE−/− × sEH−/− mice after cuff placement. n=7-8, *p<0.05.

Discussion

In the present study we determined the role of the sEH for neo-intima formation in ApoE−/− mice. In the femoral artery cuff model, we observed that lack of sEH activity was associated with attenuated neo-intima formation, reduced smooth muscle cell proliferation and attenuated pro-inflammatory gene expression. In contrast, in the carotid artery ligation model no effect of genetic deletion of the sEH was observed.

EETs are potent endogenous compounds with beneficial vascular actions 7. As the sEH limits EET availability, inhibition of this enzyme has emerged as an option to treat vascular diseases. Animal experiments which were almost exclusively performed in rodents, suggested that sEH inhibition lowers blood pressure in some hypertensive models 9;11 and that a reduction of sEH activity exhibit anti-inflammatory effects in a variety of disease conditions 14. Thus, we hypothesized that sEH inhibition should strongly prevent neo-intima formation.

It was therefore an unexpected finding that the lack of sEH activity only interfered with the neo-intima development in the femoral cuff but not in the carotid artery ligation model. The latter observation is strengthened by the recent report that the ligation-induced remodelling of the carotid artery is also sEH-independent 15. The carotid artery ligation and the femoral artery cuff model, however, differ in their consequences on NO formation, the site of injury and the accompanying processes in the adventitia. For example, the carotid artery but not the femoral cuff model is devoid of shear-stress-induced NO release. Thus in the latter, genetic knockout of the eNOS promoted disease progression 4. Moreover, the femoral cuff model exhibits high inflammatory activity, as evident by the induction of iNOS 4, and increased TNFα-expression 16. This inflammatory component is of central relevance for neo-intima formation: Direct stimulation with the toll-like receptor 4 ligand LPS further increased 17 and corticosteroids attenuated neo-intima formation in femoral artery cuff model 18.

The pathophysiology of neo-intima formation in response to carotid artery ligation also involves endothelial activation, inflammation and cytokine production 3;19;20 but the withdrawal of flow-induced production of endothelium-derived NO is considered to be the main stimulus 21. In addition, pronounced apoptosis of SMCs occurs within the first two days after the intervention 22. For other vascular injury models it has been demonstrated that the extent of the subsequent proliferation of SMCs in the media occurs in relation to the extent of SMC apoptosis 23. Apoptotic cells also have strong anti-inflammatory properties as they induce M2 macrophage polarization 24. This mechanism may limit the inflammation in the carotid ligation model. Although the present study did not focus on apoptosis, it is conceivable that the pronounced anti-inflammatory effects of sEH inhibitors are less effective in the carotid ligation model or that sEH inhibitors interfere with the apoptotic process.

Given that NO production is increased in the femoral cuff model, it should be mentioned that NO appears to play a major role in mediating the biological effects of EETs in the mouse 25. EETs activate the PI3-kinase 26, increase via AKT the activity of eNOS and protect endothelial cells from apoptosis. Importantly, knockout of sEH has also been shown to increase PI3-kinase activity which protected cardiac function after ischemia 27. Moreover, recently it was shown that the beneficial effects of sEH inhibition are not observed in the wire-injury induced vascular remodelling model of the femoral artery in C57BL/6 mice, which is characterized by endothelial denudation 15.

A large number of studies have supported the hypothesis that sEH inhibition exerts beneficial vascular and anti-inflammatory effects. Accordingly, in the present work attenuated neo-intima formation in femoral arteries of sEH−/− and sEH inhibitor treated mice were associated with reduced proliferation of cells in the media of the vessels as well as an attenuated expression of COX2, CTGF and Gro-β. Interestingly, expression of TNFα which is primarily derived from macrophages was unaffected by the lack of sEH. This suggests some specificity of the anti-inflammatory response of EETs. It has been suggested that EETs directly interfere with the activation of NFκB 28 in the vasculature and such a process would affect COX2 and Gro-β expression, as also observed in the present study. Both proteins could contribute to neo-intima formation through a chemotactic and proinflammatory effect. The control of the CTGF expression is complex and predominantly involves TGF β, hypoxia and mechanical stress 29. In addition to its pro-fibrotic effects, CTGF promotes proliferation 29 and thus attenuated CTGF expression in femoral arteries of animals which lack sEH could contribute to attenuated SMC proliferation observed in this group. Alternatively, as previously noted in cultured SMCs, sEH inhibition can attenuate the proliferation of SMCs by a direct effect on the cell cycle 30.

The final step of neo-intima formation involves the migration of SMCs from the medial layer into the subintimal space. It was previously demonstrated in rat SMCs that EETs attenuate migration activity in a transwell assay 31. Nevertheless, in the present study a specific anti-migratory effect of EETs on murine aortic vascular smooth muscle cells was not observed as DHETs were as effective as EETs in preventing migration in cultured cells (data not shown). This suggests that in vivo complex secondary effects, potentially via the action of NO, contribute to the actions of EETs or that local concentrations in the model vary from those used in culture systems and derived from plasma level determinations. Indeed, a limitation of the present study was that EETs and DHETs were only measured in the plasma but even with pooling samples it was not possible to obtain sufficient tissue for reliable mass-spectroscopy analyses.

It has been suggested that sEH inhibitors also reduce the progression of atherosclerotic disease in ApoE−/− mice 32. Although this finding might not be unexpected on the basis of our observations it should be mentioned that the pro-atherosclerotic protocol used in the latter study involved the chronic infusion of angiotensin II in combination with atherogenic diet. Angiotensin II, however, induces strong vascular inflammation 33 and high-fat diet aggravates the situation by inducing fatty liver inflammation 34. Thus, the “anti-atherosclerotic” action might rather be an anti-inflammatory one and further experiments in “aged” ApoE−/− and ApoE−/− × sEH−/− mice as well as population based studies on the different sEH polymorphisms will be needed to uncover the true contribution of sEH to this disease.

In conclusion, in the present study we provide evidence that the beneficial vascular effects of sEH inhibition extend beyond the pressure lowering effect and that sEH inhibitors may be attractive therapeutics to attenuate neo-intima formation in some disease conditions.

Condensed Abstract.

EETs possess vaso-protective properties and are metabolized by the soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH). sEH knockout or inhibition attenuated neo-intima formation in the inflammatory femoral artery cuff model but not in ligated carotid arteries of ApoE−/−. Accordingly, at the site of cuff placement, pro-inflammatory gene expression was attenuated in sEH−/− mice.

Supplementary Material

I) EET and DHET regioisomer concentration and ratio measurements in ApoE−/− vs. ApoE−/− × sEH−/−. LC/MS-MS based quantification of all EET and DHET regioisomers. N=9-10; *p<0.05.

II) EET and DHET regioisomer concentration and ratio measurements in ApoE−/−: Solvent vs. sEH inhibitor treated animals (AUDA). LC/MS-MS based quantification of all EET and DHET regioisomers. N=9-10; *p<0.05.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the excellent technical assistance of Katalin Wandzioch, Sina Bätz and Tanja Schönfelder. We thank Erik Maronde for his support concerning measurement of PKA activity.

Source of Funding: This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, by Exzellenzcluster 147 “Cardio-Pulmonary Systems”, by the Medical Faculty of the Goethe-University by the LOEWE Lipid Signalling Forschungszentrum Frankfurt (LiFF) and the NIEHS (grant R37 ER02710) and NIH HL59699.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: BDH founded Arête Therapeutics to move sEH inhibitors into clinical trials. Arête has licensed patents in the area from the University of California where BDH and CM are inventors.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Schwartz SM. Perspectives series: cell adhesion in vascular biology. Smooth muscle migration in atherosclerosis and restenosis. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2814–2816. doi: 10.1172/JCI119472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Satoh K, Berk BC. Circulating smooth muscle progenitor cells: novel players in plaque stability. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:445–447. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang PC, Qin L, Zielonka J, Zhou J, Matte-Martone C, Bergaya S, van RN, Shlomchik WD, Min W, Sessa WC, Pober JS, Tellides G. MyD88-dependent, superoxide-initiated inflammation is necessary for flow-mediated inward remodeling of conduit arteries. J Exp Med. 2008;205:3159–3171. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moroi M, Zhang L, Yasuda T, Virmani R, Gold HK, Fishman MC, Huang PL. Interaction of genetic deficiency of endothelial nitric oxide, gender, and pregnancy in vascular response to injury in mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1225–1232. doi: 10.1172/JCI1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lardenoye JH, Delsing DJ, de Vries MR, Deckers MM, Princen HM, Havekes LM, van H,V, van Bockel JH, Quax PH. Accelerated atherosclerosis by placement of a perivascular cuff and a cholesterol-rich diet in ApoE*3Leiden transgenic mice. Circ Res. 2000;87:248–253. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.3.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar A, Lindner V. Remodeling with neointima formation in the mouse carotid artery after cessation of blood flow. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:2238–2244. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.10.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsen BT, Campbell WB, Gutterman DD. Beyond vasodilatation: non-vasomotor roles of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in the cardiovascular system. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arand M, Cronin A, Adamska M, Oesch F. Epoxide hydrolases: structure, function, mechanism, and assay. Methods Enzymol. 2005;400:569–588. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)00032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung O, Brandes RP, Kim IH, Schweda F, Schmidt R, Hammock BD, Busse R, Fleming I. Soluble epoxide hydrolase is a main effector of angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45:759–765. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153792.29478.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imig JD, Zhao X, Capdevila JH, Morisseau C, Hammock BD. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition lowers arterial blood pressure in angiotensin II hypertension. Hypertension. 2002;39:690–694. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinal CJ, Miyata M, Tohkin M, Nagata K, Bend JR, Gonzalez FJ. Targeted disruption of soluble epoxide hydrolase reveals a role in blood pressure regulation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40504–40510. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morisseau C, Goodrow MH, Newman JW, Wheelock CE, Dowdy DL, Hammock BD. Structural refinement of inhibitors of urea-based soluble epoxide hydrolases. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;63:1599–1608. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)00952-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michaelis UR, Fisslthaler B, Barbosa-Sicard E, Falck JR, Fleming I, Busse R. Cytochrome P450 epoxygenases 2C8 and 2C9 are implicated in hypoxia-induced endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5489–5498. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmelzer KR, Kubala L, Newman JW, Kim IH, Eiserich JP, Hammock BD. Soluble epoxide hydrolase is a therapeutic target for acute inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9772–9777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503279102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simpkins AN, Rudic RD, Roy S, Tsai HJ, Hammock BD, Imig JD. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition modulates vascular remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00543.2009. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monraats PS, Pires NM, Schepers A, Agema WR, Boesten LS, de Vries MR, Zwinderman AH, de Maat MP, Doevendans PA, de Winter RJ, Tio RA, Waltenberger J, ‘t Hart LM, Frants RR, Quax PH, van Vlijmen BJ, Havekes LM, van der LA, van der Wall EE, Jukema JW. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha plays an important role in restenosis development. FASEB J. 2005;19:1998–2004. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4634com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hollestelle SC, de Vries MR, Van Keulen JK, Schoneveld AH, Vink A, Strijder CF, Van Middelaar BJ, Pasterkamp G, Quax PH, De Kleijn DP. Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in outward arterial remodeling. Circulation. 2004;109:393–398. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109140.51366.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pires NM, Schepers A, van der Hoeven BL, de Vries MR, Boesten LS, Jukema JW, Quax PH. Histopathologic alterations following local delivery of dexamethasone to inhibit restenosis in murine arteries. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68:415–424. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar A, Hoover JL, Simmons CA, Lindner V, Shebuski RJ. Remodeling and neointimal formation in the carotid artery of normal and P-selectin-deficient mice. Circulation. 1997;96:4333–4342. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.12.4333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawasaki T, Dewerchin M, Lijnen HR, Vreys I, Vermylen J, Hoylaerts MF. Mouse carotid artery ligation induces platelet-leukocyte-dependent luminal fibrin, required for neointima development. Circ Res. 2001;88:159–166. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudic RD, Shesely EG, Maeda N, Smithies O, Segal SS, Sessa WC. Direct evidence for the importance of endothelium-derived nitric oxide in vascular remodeling. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:731–736. doi: 10.1172/JCI1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho A, Mitchell L, Koopmans D, Langille BL. Effects of changes in blood flow rate on cell death and cell proliferation in carotid arteries of immature rabbits. Circ Res. 1997;81:328–337. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fingerle J, Au YP, Clowes AW, Reidy MA. Intimal lesion formation in rat carotid arteries after endothelial denudation in absence of medial injury. Arteriosclerosis. 1990;10:1082–1087. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.10.6.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savill J, Dransfield I, Gregory C, Haslett C. A blast from the past: clearance of apoptotic cells regulates immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:965–975. doi: 10.1038/nri957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hercule HC, Schunck WH, Gross V, Seringer J, Leung FP, Weldon SM, da Costa Goncalves AC, Huang Y, Luft FC, Gollasch M. Interaction between P450 eicosanoids and nitric oxide in the control of arterial tone in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:54–60. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.171298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang S, Lin L, Chen JX, Lee CR, Seubert JM, Wang Y, Wang H, Chao ZR, Tao DD, Gong JP, Lu ZY, Wang DW, Zeldin DC. Cytochrome P-450 epoxygenases protect endothelial cells from apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha via MAPK and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H142–H151. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00783.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seubert JM, Sinal CJ, Graves J, Degraff LM, Bradbury JA, Lee CR, Goralski K, Carey MA, Luria A, Newman JW, Hammock BD, Falck JR, Roberts H, Rockman HA, Murphy E, Zeldin DC. Role of soluble epoxide hydrolase in postischemic recovery of heart contractile function. Circulation Research. 2006;99:442–450. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000237390.92932.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Node K, Huo Y, Ruan X, Yang B, Spiecker M, Ley K, Zeldin DC, Liao JK. Anti-inflammatory properties of cytochrome P450 epoxygenase-derived eicosanoids. Science. 1999;285:1276–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de WP, Leoni P, Abraham D. Connective tissue growth factor: structure-function relationships of a mosaic, multifunctional protein. Growth Factors. 2008;26:80–91. doi: 10.1080/08977190802025602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis BB, Thompson DA, Howard LL, Morisseau C, Hammock BD, Weiss RH. Inhibitors of soluble epoxide hydrolase attenuate vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2222–2227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261710799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun J, Sui X, Bradbury JA, Zeldin DC, Conte MS, Liao JK. Inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell migration by cytochrome p450 epoxygenase-derived eicosanoids. Circ Res. 2002;90:1020–1027. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000017727.35930.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ulu A, Davis BB, Tsai HJ, Kim IH, Morisseau C, Inceoglu B, Fiehn O, Hammock BD, Weiss RH. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitors reduce the development of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein e-knockout mouse model. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008;52:314–323. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e318185fa3c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marchesi C, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Role of the renin-angiotensin system in vascular inflammation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ludwig J, McGill DB, Lindor KD. Review: nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;12:398–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1997.tb00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

I) EET and DHET regioisomer concentration and ratio measurements in ApoE−/− vs. ApoE−/− × sEH−/−. LC/MS-MS based quantification of all EET and DHET regioisomers. N=9-10; *p<0.05.

II) EET and DHET regioisomer concentration and ratio measurements in ApoE−/−: Solvent vs. sEH inhibitor treated animals (AUDA). LC/MS-MS based quantification of all EET and DHET regioisomers. N=9-10; *p<0.05.