Summary

Objective

To study factors associated with the probability of retention in antiretroviral therapy (ART) programs in West Africa.

Methods

The International epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) in West Africa is a prospective, operational, observational cohort study based on collaboration between 11 cohorts of HIV-infected adult patients in Benin, Côte d'Ivoire, Gambia, Mali and Senegal. All patients aged 16 and older at ART initiation, with documented gender and date of ART initiation, were included. For those with at least one day of follow-up, Kaplan-Meier method and Weibull regression model were used to estimate the 12-month probability of retention in care and the associated factors.

Results

14,352 patients (61% female) on ART were included in this data merger. Median age was 37 years (IQR: 31-44 years) and median CD4 count at baseline was 131 cells/mm3 (IQR: 48-221 cells/mm3). The first line regimen was NNRTI-based for 78% of patients, protease-inhibitor based for 17%, and three NRTIs for 3%. The probability of retention was 0.90 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.89-0.90) at 3 months, 0.84 (95%CI: 0.83-0.85) at 6 months and 0.76 (95%CI: 0.75-0.77) at 12 months. The probability of retention in care was lower in patients with baseline CD4 count <50 cells/mm3 (adjusted Hazard Ratio (aHR)=1.37; 95%CI: 1.27-1.49; p<0.0001) (reference CD4>200 cells/mm3, in men (aHR=1.17; 95%CI: 1.10-1.24; p=0.0002), in younger patients (<30 years) (aHR=1.10; 95%CI: 1.03-1.19; p=0.01) and in patients with low hemoglobinemia <8g/dL (aHR=1.33; 95%CI: 1.21-1.45; p<0.0001). Availability of funds for systematic tracing was associated with better retention (aHR=0.29; 95%CI: 0.16-0.55; p=0.001).

Conclusions

Close follow-up, promoting early access to care and ART and a decentralized system of care may improve the retention in care of HIV-patients on ART.

Keywords: cohort studies, HIV infection, West Africa, retention, mortality, loss to follow-up

Introduction

During the past five years, unprecedented resources have been mobilized through initiatives such as the Global Fund to fight HIV, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (Global Fund 2008) and the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR 2008) to reach the goal of universal access to HIV treatment. At the end of 2007, about 3 million people were receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) (WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF 2008), but they were only 31% of HIV-infected patients who needed ART (WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF 2008).

ART prolongs the life and improves the quality of life of HIV-infected patients, but only as long as the patient remains in care (Braitstein et al. 2006; Stringer et al. 2006; Toure et al. 2008). The effectiveness of ART of programs should be evaluated regularly using key indicators including percentage of deaths, percentage of patients lost to follow-up (LTFU), and percentage of patients remaining on ART in the program. Among these indicators, retention is the most meaningful, as poor retention in care predicts poor survival with HIV infection (Giordano et al. 2007). In lower-income countries, mortality is underestimated in HIV programs because of the misclassification of LTFU patients (Giordano et al. 2007; Anglaret et al. 2004; Bisson et al. 2008; Dalal et al. 2008; Yu et al. 2007). Program-specific factors should be identified in order to improve adherence to treatment and to achieve better outcomes for patients starting ART in developing countries. Data on individual factors and program characteristics that could explain retention are scarce (Calmy et al. 2006; Rosen et al. 2007; Tsague et al. 2008), as are data on factors associated with patient loss to follow-up (Calmy et al. 2006; Rosen et al. 2007; Tsague et al. 2008).

We hypothesized that both the characteristics of HIV care systems and the individual characteristics of patients influence retention in HIV care. We report here the one-year estimates of the retention of HIV-infected patients on ART and the factors associated with patient loss to follow-up in large HIV programs participating in the International epidemiological Database to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) in West Africa.

Methods

IeDEA West Africa collaboration

This cohort analysis was conducted within the International epidemiological Database to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) initiative (www.iedea-hiv.org), by collecting and harmonizing data from multiple HIV/AIDS cohorts from industrialized and resource-limited countries. The IeDEA collaboration aims to address research questions in the field of HIV/AIDS care and treatment, especially in lower-income countries, where most ART scaling up takes place. In the West African region, this collaboration was launched in July 2006. Since April 2008, eleven HIV/AIDS clinics for adults participate in this collaboration (www.iedeawestafrica.org). This first merger analysis includes the data from all of the participating adult's clinical centers: Benin (n=1), Côte d'Ivoire (n=6), Gambia (n=1), Mali (n=2), and Senegal (n=1). Data from Burkina-Faso and Nigeria were not yet available at the time of analysis.

Inclusion criteria and definitions

All HIV-infected patients aged of 16 years or older starting ART irrespective of the drug regimen and for whom gender and date of ART initiation were documented were eligible. The following information was recorded in the database: age, gender, body mass index, date of ART initiation, pre-therapy CD4 count, haemoglobinemia and type of ART regimen. Clinical follow-up was generally scheduled every 3 months and CD4 counts were measured every 6 months to monitor immunological response to ART. Routine viral load monitoring is generally not available.

Ethical aspects

The IeDEA West Africa collaboration was approved by the national ethics committees at country level with federal-wide assurance number identification.

Outcomes

The main outcomes of this study were (i) loss to follow-up defined as a duration of >6 months between the last visit recorded and the closing date of the database, among all HIV-infected patients who had initiated ART and at least one day of follow-up; (ii) retention (one minus the probability of death or loss to follow-up).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and comparisons between two categorical variables were done using the chi2 test and Fisher's exact test when appropriate. For survival analysis, the closing date was defined for each cohort as the date of the most recent follow-up recorded in the database. We included in this analysis only the patients with at least one day of follow-up.

In April 2008, the data set was closed for analysis after the data merger. Follow-up was censored at the date of death for deceased patients, and the date of the last visit for LTFU patients. Patients alive and in care on April 2008 were right-censored at the date of their last visit before this fixed date.

Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to estimate the probabilities of retention in care and 95% confidence interval (CI). Logrank tests were used for univariable comparison. We used random-effect Weibull regression models to estimate the hazards ratio (HR) of retention and its 95% CI, accounting for heterogeneity between the different HIV clinics (Gutierez 2002; Keiding et al. 1997).

Models included both individual patient's variables (age, gender, pre-therapy baseline CD4 cell count, baseline hemoglobinemia level, type of initial regimen, clinical stage of HIV disease defined as less advanced (CDC stage A/B or WHO stage I/II) or advanced (CDC stage C or WHO stage III/IV), baseline hemoglobinemia level and body mass index) and program level characteristics (use of phone calls, tracing methods in case of missed appointment, type and location of facilities, free access to ART and laboratory tests). All variables associated with retention in care at P values <0.25 and variables known associated with retention were included in the multivariate analysis. The multivariable analysis was performed by backward selection procedure. All analyses were performed in an intent-to-continue treatment with the SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Site description

Eleven HIV clinics for adults in urban areas participate in the IeDEA West Africa collaboration. Seven are funded through government, including 5 in university teaching hospitals. Two centres are supported by non-governmental organisations (in Abidjan) and 2 others by both public and private funds. As of April 2008, ART was free of charge in 6 of these clinics. Laboratories tests were free of charge in all centres except in 1 in Abidjan and 1 in Dakar. Only 3 sites had funds for systematic home visits and telephone calls when patients missed scheduled clinic visits (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of HIV clinics participating in the IeDEA West Africa Collaboration (N=11).

| Free access § |

Training Method |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Location | Number of patients | Type of center | Start of program | ARV | Lab* test | OI | Systematic Phone call | Systematic Home visit |

| CNHU | Cotonou, Benin | 770 | UTH | 2002 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| CePReF | Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire | 2 949 | NGO | 2004 | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| CIRBA | Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire | 1 884 | Public/Private | 2000 | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| CNTS | Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire | 421 | Public | 2005 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| MTCT-Plus | Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire | 366 | NGO | 2003 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| SMIT Abidjan | Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire | 3 865 | UTH | 2000 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| USAC | Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire | 2 421 | Public | 2000 | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| FAJARA | Banjul, Gambia | 121 | Public/Private | 2004 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gabriel Touré | Bamako, Mali | 939 | UTH | 2001 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Point G | Bamako, Mali | 290 | UTH | 2001 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| SMIT Dakar | Dakar, Senegal | 326 | UTH | 2000 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

UTH: University Teaching Hospital, NGO: Non Governmental Organization, ARV: antiretroviral therapy, OI: treatment for opportunistic infection

Lab test, Laboratory test,

as of April 2008

Study population

We included 14,352 HIV-infected patients (61.4% female) in this analysis. Median age was 37 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 31-44 years) and baseline median CD4 count (n=12,366) was 131 cells/mm3 (IQR: 48-221 cells). Among 10,564 patients for whom HIV disease was recorded, 5,580 (38.9%) had advanced HIV disease (WHO stage 3-4 or AIDS). The first-line ART regimen prescribed was NNRTI-based for 78% of patients, protease inhibitor-based for 17%, and 3 NRTIs for 3%. We summarise in Table 2 the baseline characteristics of this population of HIV-infected patients at ART initiation.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of HIV-infected patients. IeDEA West Africa Collaboration (N=14352)

| Total of patient N=14352 | Follow up > 1 day N=13102 | No follow-up N=1250 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n(%) | ||||

| Male | 5542 (38.6) | 4976 (38.0) | 566 (45.3) | <0.0001 |

| Female | 8810 (61.4) | 8126 (62.0) | 684 (54.7) | |

| Age, years, median [IQR] | 37 [31-44] | 37 [31-44] | 37 [32-44] | 0.23 |

| HIV type | <0.0001 | |||

| HIV-1 | 13107 (91.3) | 11983 (91.5) | 1124 (89.9) | |

| HIV-2 | 371 (2.6) | 342 (2.6) | 29 (2.3) | |

| Dual infected | 445 (3.1) | 421 (3.2) | 24 (1.9) | |

| Missing | 429 (3.0) | 356 (2.7) | 73 (5.8) | |

| Body mass index, Kg/m2 (n=7989) | ||||

| Median [IQR] | 21 [18-23] | 21 [18-23] | 20 [17-24] | 0.28 |

| WHO clinical stage, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| CDC (A, B) or WHO stage (l, II) | 4984 (34.7) | 4585 (35.0) | 399 (31.9) | |

| CDC (C) or WHO stage (III, IV) | 5580 (38.9) | 5351 (40.8) | 229 (18.3) | |

| Missing | 3788 (26.4) | 3166 (24.2) | 622 (49.8) | |

| CD4 counts, cells/mm3 (n=12366) | <0.0001 | |||

| Median [IQR] | 131 [48-221] | 134 [51-223] | 86 [24-187] | |

| [0-50[ | 3135 (21.8) | 2813 (21.5) | 322 (25.8) | <0.0001 |

| [50-200[ | 5503 (38.3) | 5160 (39.4) | 343 (27.4) | |

| >=200 | 3728 (26.0) | 3529 (26.9) | 199 (15.9) | |

| Missing | 1986(13.8) | 1600 (12.2) | 386 (30.9) | |

| Hemoglobinemia, g/dL (n=12366) | <0.0001 | |||

| Median [IQR] | 10.1 [8.9-11.4] | 10.1 [8.9-11.4] | 9.7 [8.3-10.9] | |

| [0-8[ | 1495 (10.4) | 1332 (10.2) | 163 (13.0) | <0.0001 |

| >=8 | 10738 (74.8) | 10046 (76.7) | 692 (55.4) | |

| Missing | 2119(14.8) | 1724(13.2) | 395 (31.6) | |

| First HAART regimen, n(%) | ||||

| 2 NRTIs + 1 INNRTI | 11213 (78.1) | 10340 (78.9) | 873 (69.8) | <0.0001 |

| 2 NRTIs + 1 PI | 2406(16.8) | 2120(16.1) | 286(17.0) | |

| 3 NRTIs | 477 (3.3) | 432 (3.3) | 45 (3.6) | |

| Others | 35 (0.2) | 30 (0.2) | 5 (0.2) | |

| Mono-bitherapy | 221 (1.6) | 180(1.4) | 40 (3.2) | |

| Year of HAART regimen, n (%) | ||||

| <2004 | 2111 (14.7) | 1821 (13.9) | 290 (23.2) | <0.0001 |

| 2004 | 3903 (27.2) | 3523 (26.9) | 380 (30.4) | |

| 2005 | 4712 (32.8) | 4359 (33.3) | 353 (28.2) | |

| 2006-2007 | 3626 (25.2) | 3399 (26.0) | 227 (18.2) | |

| Follow-up | ||||

| Follow-up > 1 days | 13102 (91.3) | |||

| Cumulative, person-years | 24620.7 | |||

| Per patient, year, median [IQR] | 1.8 [0.8-2.8] | |||

| Status at 12-month | ||||

| Dead, n (%) | 521 (4.0) | |||

| Lost to follow-up, n (%) | 2610(19.9) | |||

HAART: Highly active antiretroviral therapy; WHO: World Health Organization; CDC: Center Diseases Control and Prevention, IQR: interquartile range

Retention in program

Among the 14,352 HIV-infected patients enrolled, 1,250 (8.7%) had no follow-up visit after the initiation of ART (Table 2). Initial defaulters were more often men and had a lower baseline median CD4 count than patients with at least1 day of follow-up.

13,102 (91.3%) patients were followed up for a median of 1.8 years (IQR): [0.8-2.8] accounting for 24620.7 person-years of follow-up. During the overall study period, 521 (4.0%) patients were known to be dead, and 2,610 (19.9%) were lost to follow-up. 9,971 (76.1%) patients remained on ART 12 months after enrolment.

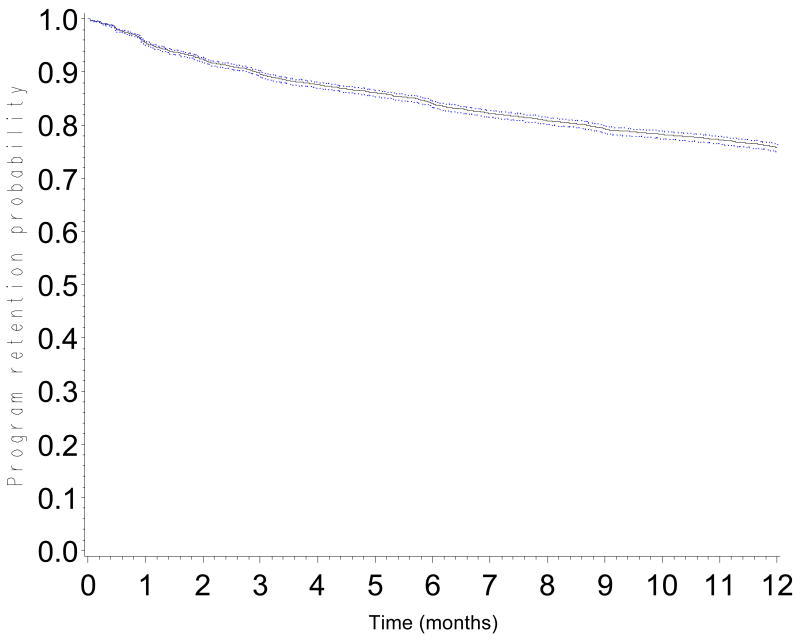

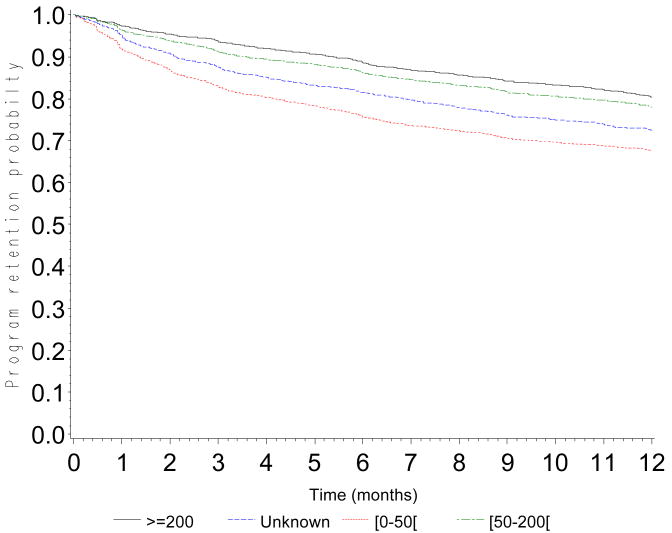

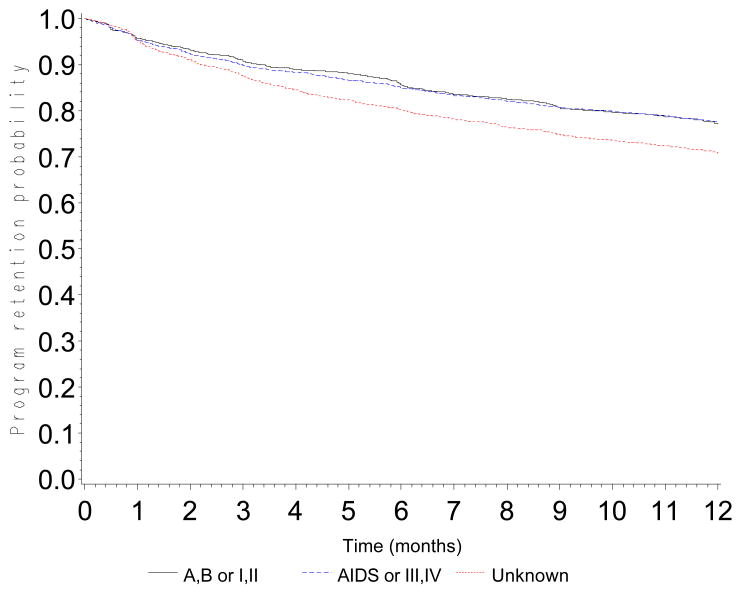

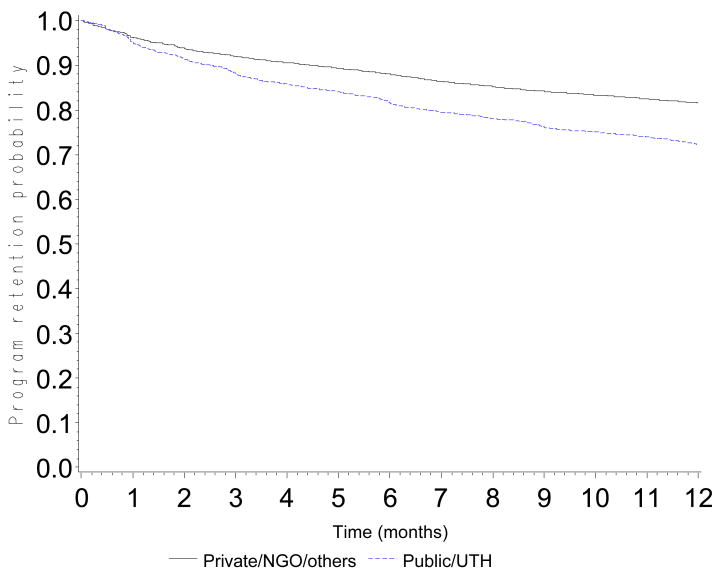

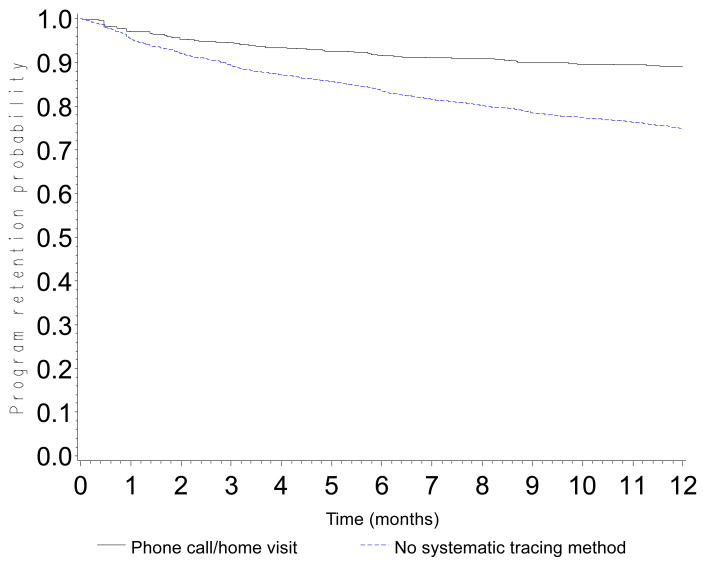

The probability of retention in the program was 0.90 (CI: 0.89-0.90) at 3 months, 0.84 (CI: 0.83-0.85) at 6 months, 0.76 (CI: 0.75-0.77) at 12 months, 0.68 (CI: 0.67-0.69) at 18 months and 0.60 (0.59-0.61) at 24 months (Figure 1). Probabilities of retention are presented according to CD4 count at baseline (Figure 2a), WHO stage (Figure 2b), type of health facility (Figure 2c) and availability of tracing methods (Figure 2d). At 12 months, the probability of retention was 0.68 (CI: 0.66-0.69) in patients with a baseline CD4 count <50 cells/mm3 and 0.80 (CI: 0.79-0.82) in patients with a baseline CD4 count >200 cells/mm3.

Figure 1.

Program retention probability in the first 12 months after ART initiation

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Program retention probability in the first 12 months after ART initiation by baseline CD4 cell count (log-rank test: p<0.0001)

Figure 2b. Program retention probability in the first 12 months after ART initiation by baseline clinical stage (log-rank test: p<0.0001)

Figure 2c. Program retention probability in the first 12 months after ART initiation by type of center (log-rank test: p<0.0001)

Figure 2d. Program retention probability in the first 12 months after ART initiation according to tracing method for patients lost to follow-up (home visit and phone call) (log-rank test: p<0.0001)

Factors associated with the retention in programs

In multivariate analysis (Table 3), the probability of retention was lower in males (adjusted Hazard Ratio (aHR): 1.17, CI: 1.10-1.24, p=0.0002), and in younger patients < 30 years old (aHR=1.10; CI: 1.03-1.19; p=0.01). Two biological factors measured at initiation of treatment were also associated with a poorer retention: a CD4 count <50 cells/mm3 (aHR=1.37; CI: 1.27-1.49; p<0.001) as compared to those with CD4 count >200 cells/mm3; and low haemoglobinemia <8g/dL (aHR=1.33; CI: 1.21-1.45; p<0.0001) as compared to those with haemoglobin level >=8 g/dL. Finally, the availability of tracing method in the programme (phone calls and systematic home visits when patients missed appointment visits) was associated with a much better retention in the program clinics at 12 months (aHR: 0.29, CI: 0.16-0.55, p=0.001).

Table 3.

Weibull survival model with random effect controlling for cohort heterogeneity, outcome was death or loss to follow-up in the first 12 months after HAART initiation. IeDEA West Africa Collaboration (N=13102).

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | CI 95% | p | HR | CI 95% | p | HR | CI 95% | p | |

| Men | 1.14 | 1.08-1.21 | 0.0004 | 1.16 | 1.10-1.24 | 0.0002 | 1.17 | 1.10-1.24 | 0.0002 |

| Age < 30 years | 1.07 | 1.00-1.14 | 0.06 | 1.10 | 1.03-1.19 | 0.01 | 1.10 | 1.03-1.19 | 0.01 |

| Baseline clinical stage (CDC A/B; WHO I/II) | |||||||||

| AIDS, WHO III and IV | 1.06 | 0.99-1.15 | 0.09 | 1.01 | 0.94-1.10 | 0.68 | - | ||

| Unknown | 1.14 | 1.04-1.24 | 0.01 | 1.14 | 1.04-1.25 | 0.01 | |||

| Baseline CD4 cell count ≥ 200 | |||||||||

| [0-50[ | 1.41 | 1.30-1.53 | <0.0001 | 1.38 | 1.27-1.50 | <0.0001 | 1.37 | 1.27-1.49 | <0.0001 |

| [50-200[ | 1.08 | 1.00-1.16 | 0.05 | 1.07 | 0.99-1.15 | 0.08 | 1.06 | 0.99-1.21 | 0.10 |

| Unknown | 1.17 | 1.06-1.29 | 0.006 | 1.18 | 1.00-1.40 | 0.05 | 1.20 | 0.98-1.49 | 0.03 |

| Baseline hemoglobin ≥ 8 g/dl | |||||||||

| [0-8[ g/dl | 1.34 | 1.23-1.47 | <0.0001 | 1.33 | 1.22-1.46 | <0.0001 | 1.33 | 1.21-1.45 | <0.0001 |

| Unknown | 1.04 | 0.96-1.14 | 0.28 | 0.98 | 0.83-1.14 | 0.73 | 0.98 | 0.84-1.15 | 0.80 |

| Systematic tracing method: phone call / Home visit | 0.28 | 0.15-0.52 | 0.001 | 0.37 | 0.19-0.70 | 0.006 | 0.29 | 0.16-0.55 | 0.001 |

| Public center / UTH | 2.06 | 0.89-4.74 | 0.08 | 1.43 | 0.79-2.59 | 0.20 | - | ||

| Free access to ARV | 1.02 | 0.39-2.66 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.55-1.58 | 0.78 | - | ||

| Free access to lab tests | 0.64 | 0.20-2.04 | 0.42 | 0.83 | 0.42-1.64 | 0.57 | - | ||

Discussion

The 1-year retention, or average chance for a patient to remain in care and on ART, was 79% in this large collaborative study with more than 15,000 patients in 5 West African countries. Not only individual factors such as gender, age, low CD4 cell count (<50 cells/mm3) and low hemoglobinemia (<8g/dL) were associated with retention, but also program characteristics such as tracing. To our knowledge this is the first report on program outcomes in more than one country in this part of Africa, where the HIV epidemic has been generalized for more than 20 years in terms of treatment programs, but the response has been generally delayed except in Senegal (Etard et al. 2006).

In terms of frequency, our results are similar to those reported by Tsague et al. (2008) in Cameroon, who reported a retention rate of 82% at 12 months. In 21 centers of Medecins Sans Frontière programs (none in West Africa), Calmy et al. (2006) reported that 82% of HIV-infected patients remained on ART at 12 months. These two studies did not include data on program characteristics. A meta-analysis on published results including 32 scientific reports from 13 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa revealed that the average retention rate at 12 months was 75% (Rosen et al. 2007). This low rate of retention in care of HIV-infected patients on ART may be the next challenge once universal access to ART has been achieved (WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF 2008).

A proportion of 19% LTFU patients at 12 months is almost five times the reported risk of death. 19% was also reported by an NGO-funded program with rapid scale-up in Côte d'Ivoire (Toure et al. 2008); 24% were reported in an urban area in Uganda (Weidle et al. 2002). However, this indicator is rarely used in the majority of reports on the mortality of HIV-infected patients in lower income countries (Lawn et al. 2008), which impairs the full interpretation of survival estimates (Anglaret et al. 2004).

The fact that the definition of LTFU varies in each program or study complicates the comparison between different settings (Rosen et al. 2007, Lawn et al. 2008). In our study, we defined patients as LTFU when they had not been in contact with the HIV clinics for at least six months and were not known to have moved or died. This definition is consistent with the largest report to date on the matter (Braitstein et al. 2006).

In this collaborative analysis, we were unable to investigate thoroughly primary reasons for LTFU. In a study conducted in South Africa in 2004-2005, 35% of HIV-infected patients could not be traced because of incorrect contact information (Dalal et al. 2008) probably given for fear of being identified as HIV-infected. In the same study, among the 48% of patients who were successfully traced, death was the most common outcome. Another investigation of patients LTFU in four facilities in northern Malawi found that 50% of them had died, 23% were alive and 27% untraceable (Yu et al. 2007). Indeed, for cultural and social reasons, many African patients on ART at advanced stage of disease return to their village to die in order to reduce the funeral costs; these patients are generally classified as LTFU. Whether this was true in our 11 participating clinics in West African capitals remains unverified but has been documented in the context of a clinical trial cohort in Abidjan (Anglaret et al. 2006). Investigating vital status by research in newspaper obituaries, telephone calls to relatives and home visits has been used to obtain more accurate information on mortality (Anglaret et al. 2006).

Another factor explaining a high rate of LTFU is that the patients find other sources of care (Stringer et al. 2006). This should normally be documented by reviewing transfer form at clinic level. However, this information is inconsistently reported, thus preventing the proper documentation of retention. In the ACONDA program in Côte d'Ivoire, which included more than 10,000 HIV-infected patients on ART, 3% had been transferred to other HIV care programs (Toure et al. 2008).

In our study, multivariable analysis identified 5 factors associated with low retention rates. The first was low CD4 cell counts (<50 cells/mm3), a factor known to be associated with early mortality in lower-income countries (Stringer et al. 2006, Toure et al. 2008, Calmy et al. 2006, Tsague et al. 2008). This favours the hypothesis that a certain proportion of patients LTFU are in fact dying. In accordance with the Cameroon report, WHO stage at ART initiation was not associated with retention (Tsague et al. 2008). However, in Côte d'Ivoire, advanced HIV disease was associated with LTFU (Toure et al. 2008). Low hemoglobin level, which is a known risk factor of disease progression in ART treated patients (Srasuebkul et al. 2009), was associated with poor retention in our study. The other individual factors associated with retention were male gender and younger age. This may be due to the higher mobility in young men as reported by Brinkhof et al. (2008). The association between retention and female sex may depend on the sex ratio of clinic attendees, itself related to the setting (Dalal et al. 2008, Brinkhof et al. 2008).

A program factor strongly associated with good retention was the availability of funds forsystematic tracing of patients who missed scheduled visits. However, this approach is expensive and not fully supported by most donors programs. Home follow-up visits seemed inefficient and relatively expensive (Stringer et al. 2006) in an urban program in Zambia, although systematic tracing can be an efficacious strategy (Braitstein et al. 2006). In Côte d'Ivoire, at 12 months, it was clear that the rate of LTFU was lower in the HIV clinics with more logistical support and experienced staff (Toure et al. 2008). The ART-LINC collaboration observed that 12-month survival was paradoxically lower in patients with passive follow-up, but this difference had to be corrected by the fact that 12% of patients were considered as LTFU in programs with active follow-up versus 19% in programs with passive follow-up (Braitstein et al. 2006). In general, our affiliated centers did not have the funds to retrieve patients who had missed their clinic visit. A cost-effectiveness analysis is under way to document the relation between the intensity and organization of effective care and its impact on the retention of patients (Losina et al. 2008).

Many strategies proposed to increase retention in HIV clinics are similar across the programs. A family-based approach is considered as one option to increase retention, but this needs to be better documented (Tonwe-Gold et al. 2009). Other strategies such as outreach initiatives, peer educators, or maintaining updated contact information during follow-up have been suggested, but none have been fully investigated. The education of HIV-infected patients regarding ART should be reinforced before the initiation of ART and at each visit, but the impact of such strategies on program retention is largely unknown.

The main limitation of the study is the underestimation of the risk of death, 4% at 12 months. This could be largely explained by the low notification of death in certain cohorts. Indeed, Lawn et al. (2008) reported in an editorial review that between 8% and 26% of patients died within the first year of ART, with most deaths occurring in the first months. In a recent systematic review, mortality was inversely associated with the rate of loss to follow-up in the program: it declined from around 60% to 20% as the percentage of patients lost to the program increased from 5% to 50% (Brinkhof et al. 2009). We addressed this limit by using a combined outcome defining retention as the complement of death and loss to follow-up. The second limitation was the lack of long-term data on retention. This is due to recent introduction of ART in most of these clinics like elsewhere except in pilot site (Etard et al. 2006). To our knowledge, long term data have not been reported in large collaborative studies in low-income countries. Finally, missing data is a common phenomenon, especially for CD4 count, at initiation of ART. In this study it could be largely attributed to the fact that we used data routinely collected from 11 cohorts in West Africa.

Program retention in care now appears to be a more reliable indicator than mortality alone in low-income countries because of the misclassification of HIV-infected patients LTFU. One important methodological recommendation for further analyses on this issue is to systematically include the LTFU effect in survival analysis. Promising approaches such as patient tracing, reimbursing transportation costs, adherence support during each follow-up visit and peer educators need to be evaluated for cost-effectiveness. More analyses are needed find out why HIV-infected adults drop out of care, and policy makers should focus on retention in care.

Acknowledgments

The International epidemiological Database to Evaluate AIDS in West Africa (IeDEA West Africa) is supported by: the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the National Institute of Allergy And Infectious Diseases (NIAID) as part of the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) (grant no. 5U01AI069919-03). The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of these institutions.

References

- Anglaret X, Toure S, Gourvellec G, et al. Impact of vital status investigation procedures on estimates of survival in cohorts of HIV-infected patients from Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2004;35:320–3. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200403010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisson GP, Gaolathe T, Gross R, et al. Overestimates of survival after HAART: implications for global scale-up efforts. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, et al. Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet. 2006;367:817–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Myer L, et al. Early loss of HIV-infected patients on potent antiretroviral therapy programs in lower-income countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008;86:559–67. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.044248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkhof MW, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Egger M. Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programs in resource-limited settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calmy A, Pinoges L, Szumilin E, et al. Generic fixed-dose combination antiretroviral treatment in resource-poor settings: multicentric observational cohort. AIDS. 2006;20:1163–9. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000226957.79847.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal RP, Macphail C, Mqhayi M, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of adult patients lost to follow-up at an antiretroviral treatment clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2008;47:101–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815b833a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etard JF, Ndiaye I, Thierry-Mieg M, et al. Mortality and causes of death in adults receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy in Senegal. AIDS. 2006;20:1181–9. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000226959.87471.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC, et al. Retention in care: a challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007;44:1493–9. doi: 10.1086/516778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierez R. Parametric frailty and shared frailty survival models. STATA. 2002:22–44. [Google Scholar]

- Keiding N, Andersen PK, Klein JP. The role of frailty models and accelerated failure time models in describing heterogeneity due to omitted covariates. Statistics in Medicine. 1997;16:215–24. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970130)16:2<215::aid-sim481>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawn SD, Harries AD, Anglaret X, et al. Early mortality among adults accessing antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:1897–908. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830007cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losina E, Toure H, Uhler L, et al. The clinical and economic impact of interventions to prevent loss to follow-up (LTFU) in resource-limited settings. PLoS Medicine. 2008;10:e174. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen S, Fox MP, Gill CJ. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Medicine. 2007;4:e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srasuebkul P, Lim PL, Lee MP, et al. Short-term clinical disease progression in HIV-infected patients receiving combination antiretroviral therapy: results from the TREAT Asia HIV observational database. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;48:940–50. doi: 10.1086/597354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringer JS, Zulu I, Levy J, et al. Rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy at primary care sites in Zambia. JAMA. 2006;296:782–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Global Fund to fight AIDS Tuberculosis and Malaria. Annual Report 2008. [30 September 2009];2008 Available at: http://www.theglobalfund.org/documents/publications/annualreports/2008/AnnualReport2008.pdf.

- Tonwe-Gold B, Ekouevi DK, Amani-Bosse C, et al. Implementing family-focused HIV care and treatment: The first two years' experience of the MTCT-Plus program in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2009;14:204–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toure S, Kouadio B, Seyler C, et al. Rapid scaling-up of antiretroviral therapy in 10,000 adults in Cote d'Ivoire:2-year outcomes and determinants. AIDS. 2008;22:873–82. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f768f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsague L, Koulla S, Kenfak A, et al. Determinants of retention in care in an antiretroviral therapy (ART) program in urban Cameroon. The Pan African Medical Journal. 2008;1 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEPFAR. U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. [30 September 2009];2008 Available at: http://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/115411.pdf.

- Weidle PJ, Malamba S, Mwebaze R, et al. Assessment of a pilot antiretroviral drug therapy programme in Uganda: patients' response, survival, and drug resistance. Lancet. 2002;360:34–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09330-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF. Towards universal access. Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. [30 September 2009];2008 Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/towards_universal_access_report_2008.pdf.

- Yu JK, Chen SC, Wang KY, et al. True outcomes for patients on antiretroviral therapy who are “lost to follow-up” in Malawi. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2007;85:550–4. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.037739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]