Abstract

Aim

To examine the relation of changes in Five-Factor personality traits (i.e., extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness to experience; Costa & McCrae, 1985), drinking motives, and problematic alcohol involvement in a cohort of college students (N=467) at varying risk for alcohol use disorders from ages 21–35.

Method

Parallel process latent growth models were estimated to determine the extent that prospective changes in personality and alcohol problems covaried as well as the extent to which drinking motives appeared to mediate these relations.

Results

Changes in neuroticism and conscientiousness covaried with changes in problematic alcohol involvement. Specifically, increases in conscientiousness and decreases in neuroticism were related to decreases in alcohol from ages 21–35, even after accounting for marriage and/or parenthood. Change in coping (but not enhancement) motives specifically mediated the relation between changes in conscientiousness and alcohol problems in addition to the relation between changes in neuroticism and alcohol problems.

Discussion

Personality changes, as assessed by a Five-Factor model of personality, are associated with “maturing out” of alcohol problems. Of equal importance, change in coping motives may be an important mediator of the relation between personality change and the “maturing out.”

Keywords: personality change, Five-Factor, alcohol use disorders, maturing out, drinking motives, prospective study

1. Introduction

Though the normative decline in alcohol problems across the mid-to-late twenties (i.e., “maturing out”; Winick, 1962; see Dawson, Grant, Stinson, & Chou, 2004; Fillmore, 1988; Johnston, O’Malley, & Bachman, 1998) has been traditionally attributed to individuals’ assuming adult roles and responsibilities (e.g., marriage and parenthood, see Bachman et al., 1997; Bachman et al., 2002; Fillmore, 1988; Jessor, Donovan, & Costa, 1991; O’Malley, 2004–2005; Yamaguchi & Kandel, 1985), recent findings suggests that personality change may also be an important mechanism in the “maturing out” of alcohol problems. Littlefield, Sher, & Wood (2009) found decreases in impulsivity and neuroticism related to decreases in alcohol problems from ages 18–35. Further, this relation held when controlling for the influence of reported adult role statuses of marriage and parenthood. More recent evidence suggests that changes in coping motives may be an important statistical mediator of the link between declines in alcohol problems and personality change (Littlefield, Sher, & Wood, 2010).

However, it remains unclear if these findings extend to other personality traits such as those represented in Five-Factor models (FFM) of personality, which are derived from different theoretical assumptions (i.e., a lexical approach; e.g., Allport & Odbert, 1936; see John, 1990; Wiggins & Trapnell, 1997) and include personality constructs (i.e., extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness to experience) that are not consistently isomorphic with previously used personality measures. In a recent meta-analysis, Malouff, Thorsteinsson, Rooke, and Schutte (2007) examined the relationship between the Five-Factor Model of personality and alcohol involvement. Synthesizing results across 20 studies, Malouff et al. found that alcohol involvement associated with low conscientiousness, low agreeableness, and high neuroticism.

Though prior research suggests that specific Five-Factor traits are correlated with alcohol involvement, it remains unclear how developmental changes in these traits across time may relate to changes in alcohol involvement. Along with dramatic decreases in alcohol problems, emerging and young adulthood is associated with changes in major personality traits such as those measured by Five-Factor models of personality (see Roberts, Walton, & Viechtbauer, 2006, for a meta-analysis). These changes trend towards personality structures that reflect greater self-control, agreeableness, and emotional stability as people reach adulthood (i.e., the maturity principle; Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005), though significant individual differences (i.e., interindividual differences in intraindividual variation) in personality change have also been documented (see Roberts & Mroczek, 2008). Thus, considering the Malouff et al. review of alcohol involvement and Five-Factor models of personality and our previous findings that demonstrated a relation between changes in alcohol problems and changes in neuroticism and impulsivity, we hypothesized that intraindividual changes in conscientiousness, agreeableness, and neuroticism would be associated with changes in alcohol problems from during emerging and young adulthood. To address the possibility that correlated change merely reflects correlated baselines (i.e., intercepts), we also explored alternative model specifications to evaluate the extent that correlated change could be demonstrated after statistically addressing the associations due to baseline correlations.

Finally, we also tested whether changes in drinking motives, specifically coping motives (i.e., drinking to alleviate negative emotional states) and enhancement motives (i.e., drinking to enhance positive emotional states), mediated relations of changes in Five-Factor personality constructs with changes in problematic alcohol involvement (see Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels; 2005; Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels; 2006 for reviews of the alcohol-motive-personality relation). That is, we explored whether our recent findings that coping (but not enhancement) motives were a significant statistical mediator of the respective relation between changes impulsivity (measured by items from the Eysenck Personality Inventory [EPI; Eysenck & Eysenck, 1968] and the short-form of the Tri-Dimensional Personality Questionnaire [TPQ; Cloninger, 1987; Sher, Wood, Crews, & Vandiver, 1995]) and neuroticism (measured by the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire [EPQ; Eysenck, & Eysenck, 1975]) with changes in alcohol problems (Littlefield, Sher, & Wood, 2010) extend to the potential relation between changes in Five-Factor personality dimensions and changes in problematic alcohol involvement.

2. Method

2.1 Participants and Procedure

Data were drawn from a prospective high-risk study on family history of alcoholism (FH) and other correlates of alcoholism (see Sher, Walitzer, Wood, & Brent, 1991, for a full description of the study). The baseline sample comprised of 489 freshmen (46% male, mean age = 18.2) from a large Midwestern University. Based on criteria discussed below, half (51%) of the respondents were classified as FH positive (FH+). Respondents were prospectively assessed seven times over 16 years (roughly at ages 18, 19, 20, 21, 25, 29, and 35) by both interview and paper-and-pencil questionnaire. The Five-Factor personality constructs in the current analyses were assessed at ages 21–35 and thus longitudinal measures in the current paper are limited to this assessment period. In all, over 84% of participants were retained over the first 11 years of the study, and over 78% were retained through Year 16 (mean age = 34.5). The current study uses Wave 4 (when participants averaged 21 years of age) as the baseline because this was the first measurement occasion that employed a five-factor model of personality. Four hundred sixty-seven participants (96% of age 18 baseline) completed all Wave 4 baseline assessments.

2.2 Measures

2.21 Family history of alcoholism

At baseline, criteria from the Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST; Selzer, Vinokur, & van Rooijen, 1975), adapted to measure paternal and maternal drinking problems (F-SMAST and M-SMAST; Crews & Sher, 1992), and the Family History-Research Diagnostic Criteria interview (FH-RDC; Endicott, Andreasen, & Spitzer, 1978), were used to diagnose paternal family history of alcoholism (FH). A positive FH was coded if the biological father scored a 4 or more on the F-SMAST (see Sher et al., 1991, for additional details concerning F-SMAST criteria) and met FH-RDC criteria for alcoholism. If no first-degree relative received a diagnosis of alcohol, drug abuse, or antisocial personality disorders, and there was no alcohol or drug use disorder in a second-degree relative, negative FH was coded. In order to control for the potential influence of sex and FH on alcohol involvement, personality, as well as marital and parental status, sex and FH were entered as exogenous variables in all bivariate growth models.

2.22 Problematic alcohol involvement

A sum of 27 items consisting of both negative consequences associated with drinking and symptoms related to alcohol dependence (consistent with the alcohol dependence syndrome described by Edwards & Gross, 1976) was calculated at each wave. Items were based on items from the MAST and additional items were generated to produce a comprehensive list of negative consequences of alcohol consumption and dependence symptomatology (see Sher et al., 1991). Participants were asked if in the past year they had experienced alcohol related consequences/symptoms (e.g., In the past year, have you… “Gotten in trouble at work or school because of drinking?”). Internal consistency, as measured by coefficient alpha (α), was .90 at age 21, .89 at age 25, .90 at age 29, and .90 at age 35.

2.23 Personality

When participants were, on average, 21, 25, 29, and 35, a 60-item short version of the NEO-PI (Costa & McCrae, 1985), the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI; Costa & McCrae, 1989) was used to assess the personality dimensions of extraversion (α=.80–.82), agreeableness (α=.77–.81),, conscientiousness (α=.83–.84), neuroticism (α=.85–.87), and openness to experience (α=.74–.77; see Martin & Sher, 1994, for more details).

2.24 Marriage/Parenthood

To assess the influence of marriage/parenthood on the association between changes in problematic alcohol involvement and personality, an “overall” marriage and/or parenthood variable was constructed so that participants who were married (and never divorced) and/or reported they had children at the fifth, sixth, or seventh assessment period were scored as a “1”, and participants who were not married across these assessment periods or reported they were divorced at any of these assessment periods and did not report having children at any assessment period were scored a “0”.

2.25 Drinking motives

Coping and enhancement motives were assessed using items derived from a tension-reduction drinking motives composite developed by Sher et al. 1991 (see Sher et al., 2004 for more details) with items adapted from those used by Cahalan, Cisin, and Crossley (1969) when participants were, on average, 18, 19, 20, 21, 25, 29, and 35.. Coping included four items (e.g., “I drink to forget my worries”). Enhancement included one item (i.e., “I drink to get high”). Composites were created for coping motives using the sum of the items (α = .84–.86)

2.3 Analytic Procedure

First, Latent Growth Modeling (LGM) was used to examine if changes in problematic alcohol use were related to changes in Five-Factor personality traits. The approach used here is detailed in Littlefield, Sher, and Wood (2009) and similar methods have been used elsewhere to examine the correlated change of personality with other constructs of interest (e.g., Scollen & Diener, 2006). These models examine the development of individuals on one or more outcome variables over time. Further, the initial relation of personality and alcohol involvement as well as the relation of changes in the respective constructs of personality and alcohol problems can also be estimated in these models. Additional variables (e.g., marital/parental status) can then be added to examine the influence of these variables on the relation between changes in personality and alcohol problems. Alternative modeling specifications that account for baseline correlations between personality and alcohol problems can also be explored to insure that findings of correlated changes are not dependent upon correlated baselines.

Second, to examine changes in drinking motives as a mediator in the relation between changes in personality and alcohol problems, parallel process latent growth modeling (LGM) was used (Cheong, MacKinnon, & Khoo, 2003; MacKinnon, 2008; see Littlefield, Sher, & Wood, 2010). Briefly, when the antecedent (i.e., personality), mediating (i.e., drinking motives) and outcome (i.e., alcohol problems) variables are measured repeatedly over time, growth of the X, M, and Y variables can be viewed as three separate processes (Cheong et al., 2003; MacKinnon, 2008). Evidence for mediation is established when the trajectory of the antecedent variable significantly relates to the trajectory (i.e., slope) of the mediator, which, in turn, relates to the trajectory of the outcome (Cheong et al., 2003; MacKinnon, 2008). Confidence intervals for these mediated effects in parallel process LGM are estimated using the Asymmetric Confidence Interval (ACI) method (see MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002; MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004; for more details).

3. Results

LGM was used to examine the respective changes in extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness to experience, and problematic alcohol involvement. LGMs were estimated using the statistical package Mplus Version 5.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2007). To allow for analysis of data containing missing values, all LGMs were conducted using full information maximum likelihood estimation, which assumes that data are missing at random. Participants who reported abstaining from alcohol across all assessments (n = 6) were excluded from all analyses. All structural models discussed below exhibited adequate fit to the data (i.e., CFI > .90; RMSEA & SRMR < .08; Kline, 2005). Mean-level changes in extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness to experience, and problematic alcohol involvement are shown in Figure 1. Univariate latent growth models of these constructs indicated that neuroticism, openness to experience, and problematic alcohol involvement significantly decreased from ages 21–35 whereas conscientiousness and agreeableness significantly increased during this time frame1.

Figure 1.

Observed and estimated mean-level changes (with standard errors) for openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism, and past-year problematic alcohol involvement. Reported means and prevalences were calculated from the respective univariate growth models for each construct. N=467.

The extent of correlated change in personality and problematic alcohol involvement was examined in a series of bivariate latent growth models. Based on the mean-level patterns of data (see Figure 1) as well as tests of model fit2, all bivariate LGMs consisted of an intercept and a nonlinear slope (i.e., the slope loading for the last assessment was freely estimated) for each construct of interest. In order to ease interpretability, the freely estimated slope loadings (at the final measurement occasion) for the respective alcohol and personality constructs in each bivariate growth model were constrained to be equal3. Sex and FH were included as exogenous variables (i.e., exerting a direct influence on all study constructs) and marriage and/or parenthood were included as potential mediators4.

The five separate baseline bivariate growth models (one for each personality construct) estimated were consistent with the findings from the Malouff et al. (2007) meta-analysis; Intercepts of agreeableness (β = −.26, p<.001) and conscientiousness (β = −.33, p<.001) negatively correlated with initial levels of alcohol problems, whereas the intercept of neuroticism positively correlated (β= .41, p<.001) with alcohol problems. Further, and of primary interest, the slope of conscientiousness negatively correlated with the slope of alcohol problems (β = −.34, p<.01), whereas the slope of neuroticism positively correlated with the slope of alcohol problems (β = .44, p<.01). These findings are illustrated in Panel A of Figure 2 and suggest that respective increases in conscientiousness and decreases in neuroticism are related to decreases in problematic alcohol involvement from ages 21–35, even after accounting for marriage/parenthood during this time. Though initial levels of agreeableness and alcohol problems were positively correlated, the slopes of these constructs did not significantly correlate across time (β = −.19, p=.25). Neither the respective intercepts nor slopes of openness to experience or extraversion were significantly correlated with problematic alcohol involvement intercept or slope.

Figure 2.

Bivariate latent growth model for conscientiousness and neuroticism with problematic alcohol involvement. Panel A indicates the respective bivariate growth models of conscientiousness and neuroticism with problematic alcohol involvement, controlling for marriage and/or parenthood. Panel B indicates the respective bivariate growth models of conscientiousness and neuroticism with problematic alcohol involvement, controlling for marriage and/or parenthood and initial levels of personality and alcohol involvement. Panel C indicates the respective bivariate growth models of conscientiousness and neuroticism with problematic alcohol involvement, controlling for initial levels of personality and alcohol involvement and with the intercept of alcohol problems regressed onto the respective intercepts of conscientiousness and neuroticism and the slope of alcohol problems regressed onto the respective slopes (and intercepts) of conscientiousness and neuroticism. All within-construct and across-construct covariances were estimated but estimates are not presented. All variables were controlled for family history of alcoholism and sex. All coefficients are standardized. *p<.05, **p<.01,***p<.001.

To assess whether correlated changes in personality and alcohol problems can be accounted for by the initial relationship of alcohol problems, alternative model specifications were then employed for the respective relation of changes in conscientiousness and neuroticism with problematic alcohol involvement (see Figure 2). As illustrated in panel B, models that specified directional paths between the intercept and slopes, both within and across constructs (i.e., changes in alcohol problems and personality are controlled for the initial level of these constructs), were estimated. In this model specification the significant correlations between changes in personality and changes in alcohol problems were maintained. Thus, it appears that the respective changes in conscientiousness and neuroticism correspond with changes in alcohol involvement, even after accounting for the initial relationship of alcohol involvement and personality as well as marital and parental status.

3.1 Mediational Analyses

As displayed in Panel C, in order to establish a directional model necessary for meditational analyses, the relation of initial level (intercept) as well as changes (slope) in personality and alcohol problems was modeled as directional paths. Specifically, the intercept of alcohol problems was regressed onto the respective intercepts of conscientiousness and neuroticism and the slope of alcohol problems was regressed onto the respective slopes (and intercepts) of conscientiousness and neuroticism. Building on this model, parallel process mediational models were then employed to address if the relation between changes in personality (conscientiousness and neuroticism) and alcohol problems can be accounted for by changes in drinking motives. To assess specific (i.e., unique) mediation, the coping motive intercept was controlled for the intercept of enhancement motive and coping motive slope was controlled for the intercept and slope of enhancement motive; in a corresponding fashion, enhancement motive intercept was controlled for the intercept of coping motive and enhancement motive slope was controlled for the intercept and slope of coping motives.

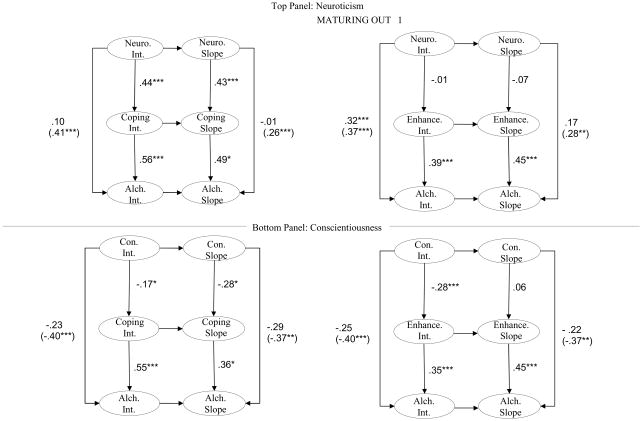

Results of these analyses are displayed in top panel of Figure 3 (for neuroticism) and bottom panel of Figure 3 (for conscientiousness) 5. Coping motive slope (IE= .210, 95% CI = .019, .479) significantly mediated the relation between neuroticism and alcohol problems when controlling (as previously outlined) for enhancement growth factors. Controlling for coping intercept and slope, the relation between changes in neuroticism with changes in enhancement was statistically nonsignificant; thus, enhancement motives were not a significant mediator between neuroticism slope and alcohol problem slope (IE = −0.031, 95% CI = −.158, .089).

Figure 3. Parallel Process Latent Growth Models of Neuroticism (top panel), Conscientiousness (bottom panel), Drinking Motives, and Alcohol Problems.

Neuro. = neuroticism. Con. = conscientiousness. Enhance = Enhancement. Alch. = Alcohol Problems. All within-construct and across-construct paths were estimated but estimates not presented. Total effects between neuroticism (top panel), conscientiousness (bottom panel), and alcohol problems are displayed in parentheses. All variables were controlled for family history of alcoholism and sex. Further, coping intercept was controlled for enhancement intercept. Coping slope was controlled for enhancement intercept and slope. Enhancement intercept was controlled for coping intercept. Enhancement slope was controlled for coping intercept and slope. All coefficients are standardized.*p<.05, **p<.01,***p<.001.

Regarding conscientiousness, coping motive slope significantly mediated the relation between the respective slopes of conscientiousness and alcohol problems (IE= −.100, 95% CI = −.257,−.000; see Figure 3, bottom panel). Further, controlling for coping motives slope, the relation between conscientiousness slope with enhancement slope was statistically nonsignificant; consequently, enhancement motives slope (IE = .026, 95% CI = −.070, .128) was not a significant mediator between conscientiousness and alcohol problems.

4. Discussion

We (Littlefield et al., in 2009) previously demonstrated that changes in alcohol problems were correlated with changes in impulsivity and EPQ neuroticism from ages 18–35, accounting for marriage and/or parenthood. The current paper extended these findings in several important ways. First, we conceptually replicated these findings by demonstrating changes in the Five-Factor personality traits of neuroticism and conscientiousness were correlated with changes in problematic alcohol involvement from ages 21–35. Specifically, increases in conscientiousness and decreases in neuroticism were related to decreases in problematic alcohol involvement from ages 21–35, accounting for marriage and/or parenthood. Further, alternative model specifications suggested that these corresponding changes cannot be accounted for by the initial relation between these personality constructs with alcohol involvement. Additionally, as was recently demonstrated in analyses using impulsivity and EPQ neuroticism (Littlefield et al., 2010), coping (but not enhancement) motives appeared to be a significant mediator of the respective relation between changes in neuroticism and conscientiousness with alcohol problems. Although our own (Martin & Sher, 1994; Trull & Sher, 1994) and other prior research has shown that alcohol involvement is associated with specific Five-Factor personality constructs (i.e., low conscientiousness, low agreeableness, and high neuroticism; Malouff et al., 2007), this is the first study to our knowledge to show that changes in Five-Factor conscientiousness and neuroticism correspond to changes in problematic alcohol involvement. These findings provide further support that a developmental framework in which changes in these constructs are viewed in the context of each other and should be considered in understanding the course of alcohol problems.

Second, coupling the results of the current findings with our previous paper (Littlefield et al., 2009), changes of problematic alcohol involvement appear to correspond to a variety of personality constructs drawn from related yet distinct models of personality. Littlefield et al. (2009) utilized measures of personality derived from the biologically based “Big Three” models of personality of Eysenck (Eysecnk & Eysecnk, 1975) and Cloninger (1987), whereas the current findings utilize measures from the questionnaire driven Five-Factor model of personality (Costa & McCrae, 1985). This suggests that correlated change of problematic alcohol with specific personality constructs (especially neuroticism) is robust across various models of personality.

Third, results suggest that these corresponding changes cannot be accounted for by marriage and/or parenthood or the initial relation between the personality constructs with alcohol involvement. These findings are important as they provide further evidence of the robustness of the significant correlated change between personality and problematic alcohol involvement.

Fourth, current findings suggest that coping motives are a significant statistical mediator of the relation between Five-Factor personality and problematic alcohol involvement. These findings parallel those of Littlefield et al. (2010) and suggest that changes coping motives may play an integral role in the link between changes in personality and alcohol problems. Notably, though enhancement motives were not found to be significant statistical mediators of the relation between Five-Factor personality and alcohol problems, the direct relation between changes in both neuroticism and conscientiousness with changes in alcohol problems became non-significant when enhancement motives were included in the model (see bottom panel, Figure 3). However, changes in enhancement motives from ages 21–35 did not significantly relate to either change in conscientiousness or neuroticism across this time span. Thus, although changes in enhancement motives appears to explain important variance in changes in alcohol problems, the lack of relation between enhancement motives and personality precludes enhancement motives from being considered as a statistical mediator of the relation between changes in personality and alcohol problems (see Cheong et al., 2003; MacKinnon, 2008).

Notably, though initial levels of agreeableness and problematic alcohol involvement were linked, changes in these constructs were not significantly related. Several possible reasons could account for this finding. First, though the relation between the slope of agreeableness and problematic alcohol involvement was not statistically significant (p=.25), the correlation was −.19, indicating a modest, yet not trivial (i.e., small-to-moderate), effect size. This suggests that perhaps a lack of power or large standard errors may have contributed to the lack of statistical significance. Second, the Malouff et al. (2007) meta-analysis found that the relation between agreeableness and alcohol involvement were limited to cross-sectional studies; agreeableness failed to predict future alcohol involvement in longitudinal studies. Though speculative, this may suggest that the relation between agreeableness and alcohol involvement may be developmentally limited or related to specific environmental risks (e.g., Park, Sher, Wood, & Krull, 2009).

Several limitations of the current study should be noted. The sample of the current study was initially drawn from first-time, predominately White (93%) college freshman entering a large university. These sample characteristics limit the generalizability of findings to non-college attending populations and to other racial/ethnic groups. Moreover, the sample size was not large enough to allow separate LGMs for family history positive/negative individuals or for men/women to be conducted. Additionally, the FFM scale employed, the NEO-FFI, does not include facet-level information and so fails to resolve potentially important aspects of personality that may be most relevant for understanding psychosocial maturing and “maturing out” of problematic alcohol use. Further, enhancement motives were only assessed by one-item (i.e., “I drink to get high”), though previous analyses provide support of the validity of the one-item measure (see Littlefield et al., 2010, for more details). Also, though the use of longitudinal data provide better estimates of mediation than cross-sectional data, the current data are still correlational in nature and thus causal conclusions regarding the current findings should be viewed with caution (see Littlefield et al., 2010, for a discussion). Finally, although initial measurement occasions for personality varied across studies (i.e., participants were on average 18 in Littlefield et al., 2009 and Littlefield et al., 2010 and were on average 21 in the current study using NEO-FFI personality measures), data for these analyses were taken from the same dataset as our previous work examining changes in personality and alcohol involvement (i.e., Littlefield et al., 2009; Littlefield et al., 2010). Thus, replicating the current findings in other samples would strengthen the conclusions reached in this paper.

In summary, results of the current analyses extend the previous findings of correlated change of personality and alcohol involvement to Five-Factor personality traits. Specifically, increases in conscientiousness and decreases in neuroticism are related to decreases in problematic alcohol involvement from ages 21–35. These relations held when accounting for marriage and/or parenthood and for the initial relation between the personality constructs and alcohol involvement. Additionally, coping motives appear to be an important mediator of these relations. Future research should build on these findings by considering a developmental framework in which changes in these constructs are viewed in the context of each other and by examining other factors that may contribute to the correlated change between problematic alcohol involvement and personality.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Kristina M. Jackson, Julia A. Martinez, and Amelia E. Talley for their insightful comments. Also, we thank the staff of the Alcohol, Health, and Behavior and IMPACTS projects for their data collection and management.

Role of Funding Sources

Preparation of this article was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants T32 AA13526, R01 AA13987, R37 AA07231 and KO5 AA017242 to Kenneth J. Sher and P50 AA11998 to Andrew Heath.

Footnotes

Results from these analyses, as well as the zero-order correlations among the personality constructs and problematic alcohol involvement, marital status, parental status, biological sex, and family history of alcoholism are available from the first author on request.

Available from the first author on request.

To further reduce interpretive ambiguity concerning the correlated slopes presented in the primary analyses, supplementary analyses were conducted that dropped the last point of assessment (age 35) and estimated linear growth from ages 21–29. The results from these analyses are consistent in direction, magnitude, and significance as those presented in the primary analyses of the current paper and are available from the first author on request.

In order to focus on drinking motives as mediators of the relation between changes in personality and alcohol problems, marriage and/or parenthood as potential mediators were precluded in the bivariate growth models that modeled directional relations between personality and alcohol (illustrated in Panel C of Figure 2).

Patterns of mean-level changes in coping and enhancement motives can be found in Littlefield et al., 2010. Results regarding the modeling of LGM of drinking motives from ages 21–35 are available from the first author upon request.

Contributors

Author Sher and associates collected data for the study. Authors Littlefield and Sher selected the study topic. Author Littlefield conducted the literature search, conducted data analyses, and wrote the first draft of the Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion sections of the paper. Authors Sher and Wood provided input regarding data analyses. All authors participated in manuscript revisions and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allport GW, Odbert HS. Trait names: A psycho-lexical study. Psychological Monographs. 1936;47 (1 Whole No. 211) [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, Bryant AL, Merline AC. The decline of substance use in young adulthood: Changes in social activities, roles, and beliefs. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE. Smoking, drinking, and drug use in young adulthood: The impacts of new freedoms and new responsibilities. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Roberts BW, Shiner RL. Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:453–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong J, MacKinnon DP, Khoo ST. Investigation of mediational processes using parallel process latent growth curve modeling. Structural Equation Modeling. 2003;10:238–262. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM1002_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR. Tridimensional personality questionnaire (TPQ) Washington University; 1987. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Costa P, Jr, McCrae R. The NEO Personality Inventory Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Costa P, McCrae R. NEO PI/FFI Manual Supplement. Odessa, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Crews T, Sher KJ. Using Adapted Short MASTs for Assessing Parental Alcoholism: Reliability and Validity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1992;16:427–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb01420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou SP. Another look at heavy episodic drinking and alcohol use disorders among college and noncollege youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:477–488. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Gross MM. Alcohol dependence: provisional description of a clinical syndrome. British Medical Journal. 1976;1:1058–1061. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6017.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Andreasen N, Spitzer RL. Family History-Research Diagnostic Criteria (FH-RDC) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Services; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Services; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore KM. Alcohol use across the life course. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Alcoholism and Drug Addiction Research Foundation; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Donovan JE, Costa FM. Beyond adolescence: Problem behavior and young adult development. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- John OP. The “Big Five” factor taxonomy: Dimensions of personality in the natural language and in questionnaires. In: Pervin LA, editor. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. New York: Guilford; 1990. pp. 66–100. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. The development of heavy drinking and alcohol-related problems from ages 18 to 37 in a U.S. national sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;61:290–300. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche EN, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Who drinks and why? A review of socio-demographic, personality, and contextual issues behind the drinking motives in young people. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1844–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield A, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Is ‘maturing out’ of problematic alcohol involvement related to personality change? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:360–374. doi: 10.1037/a0015125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield A, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Do Changes in Drinking Motives Mediate the Relation between Personality Change and “Maturing Out” of Problem Drinking? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:93–105. doi: 10.1037/a0017512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouff J, Thorsteinsson E, Rooke S, Schutte N. Alcohol involvement and the five factor model of personality: A meta-analysis. Journal of Drug Education. 2007;37:277–294. doi: 10.2190/DE.37.3.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin ED, Sher KJ. Family history of alcoholism, alcohol use disorders and the five-factor model of personality. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:81–90. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide [Computer software and manual] 5. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley P. Maturing out of problematic alcohol use. Alcohol Research and Health. 2004/2005;28:202–204. [Google Scholar]

- Park A, Sher KJ, Wood PK, Krull JL. Dual mechanisms underlying accentuation of risky drinking via fraternity/sorority affiliation: the role of personality, peer norms, and alcohol availability. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:241–245. doi: 10.1037/a0015126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Mroczek DK. Personality trait stability and change. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2008;17:31–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Walton KE, Viechtbauer W. Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:1–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scollon CN, Diener E. Love, work, and changes in extraversion and neuroticism over time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:1152–1165. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer M, Vinokur A, van Rooijen L. A self-administered Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST) Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1975;36:117–126. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1975.36.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Walitzer KS, Wood P, Brent EE. Characteristics of children of alcoholics: Putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:427–448. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Wood M, Crews T, Vandiver TA. The Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire. Reliability and validity studies and derivation of a short form. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:195–208. [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Sher KJ. Relationship between the five-factor model of personality and Axis I disorders in a nonclinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:350–360. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JS, Trapnell PD. Personality structure: the return of the Big Five. In: Hogan R, Johnson JA, Briggs SR, editors. Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1997. pp. 737–65. [Google Scholar]

- Winick C. Maturing out of narcotic addiction. Bulletin on Narcotics. 1962;14:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K, Kandel D. On the resolution of role incompatibility: Life event history analysis of family roles and marijuana use. American Journal of Sociology. 1985;90:1284–1325. [Google Scholar]