Abstract

In mammalian cells, the “Golgi Reassembly and Stacking Protein” (GRASP) family has been implicated in Golgi stacking, but the broader functions of GRASP proteins are still unclear. The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains a single nonessential GRASP homolog called Grh1. However, Golgi cisternae in S. cerevisiae are not organized into stacks, so a possible structural role for Grh1 has been difficult to test. Here we examined the localization and function of Grh1 in S. cerevisiae and in the related yeast Pichia pastoris, which has stacked Golgi cisternae. In agreement with earlier studies indicating that Grh1 interacts with COPII vesicle coat proteins, we find that Grh1 colocalizes with COPII at transitional ER (tER) sites in both yeasts. Deletion of P. pastoris Grh1 had no obvious effect on the structure of tER-Golgi units. To test the role of S. cerevisiae Grh1, we exploited the observation that inhibiting ER export in S. cerevisiae generates enlarged tER sites that are often associated with the cis-Golgi. This tER-Golgi association was preserved in the absence of Grh1. The combined data suggest that Grh1 acts early in the secretory pathway but is dispensable for the organization of secretory compartments.

Keywords: Golgi, GRASP, stacking, transitional ER, ER exit sites, COPII

Introduction

The Golgi cisternae in most eukaryotes are organized into stacks (1), but the mechanisms that generate this organization have been elusive. Isolated Golgi stacks can be converted to individual cisternae by protease treatment, suggesting that proteinaceous cross-bridges hold the cisternae together (2). Candidate stacking proteins include the “Golgi Reassembly and Stacking Protein” or GRASP family of peripheral membrane proteins (3–5). GRASPs are not essential for secretion (6–8), but might help to define Golgi organization. Mammalian GRASP65 was identified as a factor needed for the post-mitotic reassembly of Golgi stacks in vitro and in vivo (3, 5, 9). GRASP65 is present on early Golgi compartments, where it forms a functional complex with the coiled-coil protein GM130 (3, 10). Simultaneous depletion of the Drosophila homologs of GRASP65 and GM130 disrupted Golgi structure (7). Depletion of mammalian GRASP65 reduced the number of cisternae per stack but did not eliminate Golgi stacking (8), possibly because mammalian cells also contain a second GRASP protein called GRASP55 that localizes to the medial Golgi (11). Indeed, double depletion of GRASP65 and GRASP55 was recently found to cause extensive loss of Golgi stacking (12). Phosphorylation of GRASP65 and GRASP55 by mitotic kinases promotes Golgi breakdown during mitosis (13–16). These combined results fit with a model in which mammalian Golgi cisternae are held together by oligomeric GRASP complexes whose oligomerization can be regulated by phosphorylation (5, 16).

How general is this structural role of GRASPs? Although GRASPs are associated with Golgi and pre-Golgi compartments in many organisms (6, 7, 17–19), cisternal stacking is unlikely to be the sole function of these proteins. Higher plants contain prominent Golgi stacks but no detectable GRASP homologs (17, 20). Even in mammalian cells, GRASPs have been implicated in processes distinct from Golgi stacking. Morphological studies uncovered requirements for GRASP65, GM130, and GRASP55 in the lateral fusion of mammalian Golgi stacks into a Golgi ribbon (13, 21, 22). Moreover, GRASPs seem to have nonstructural roles in secretion. GRASP65 and GRASP55 bind to the cytosolic tails of certain cargo proteins and facilitate their transport through the secretory pathway (23–25), and GRASP65 provides a binding site on the Golgi for the polo-like kinase Plk1 (26). GRASP homologs in Dictyostelium and Drosophila were shown to be important for unconventional secretory pathways that bypass the Golgi (17, 27, 28). These findings suggest that the activities of GRASPs have diversified during evolution (29), and they highlight the importance of defining the primary, conserved function of the GRASP family.

Budding yeasts are a promising experimental system for studying GRASP function. Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains a single GRASP homolog called Grh1 that associates peripherally with compartments of the early secretory pathway (6). Grh1 is not essential, but may participate in vesicle tethering at the ER-Golgi interface. A potential role for Grh1 in Golgi organization was not previously investigated because S. cerevisiae has a nonstacked Golgi consisting of individual cisternae scattered throughout the cytoplasm (30, 31). To circumvent this limitation, we identified a Grh1 homolog in the budding yeast Pichia pastoris, which has Golgi stacks (32, 33). In both S. cerevisiae and P. pastoris, we examined Grh1 localization as well as the effects of disrupting the GRH1 gene. Our findings suggest that Grh1 plays a nonstructural role at an early stage of the secretory pathway.

Results

Grh1 colocalizes with COPII in P. pastoris

To explore the function of Grh1, we examined its location in S. cerevisiae and P. pastoris cells. The P. pastoris homolog of Grh1 had not previously been described, so we identified a unique GRH1 gene by searching a P. pastoris genomic DNA database (Figure S1). This information enabled us to add C-terminal fluorescent protein tags to Grh1 in both yeasts. A previous report indicated that S. cerevisiae Grh1 localizes to the cis-Golgi (6). However, we decided to revisit this issue because of reports that S. cerevisiae Grh1 interacts with COPII coat proteins (6, 34–36), which are found at tER sites rather than the Golgi (33).

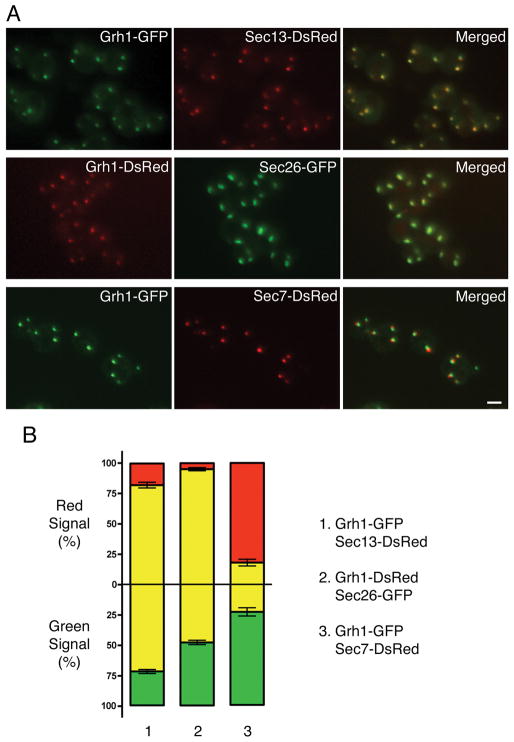

In P. pastoris, tER and Golgi structures are closely associated with each other but can be partially resolved by fluorescence microscopy (33, 37). We tagged P. pastoris Grh1 with GFP or DsRed, and compared the localization of Grh1 to that of either the tER marker Sec13 (a component of the COPII coat), or the early Golgi marker Sec26 (a component of the COPI coat), or the late Golgi marker Sec7 (a guanine nucleotide exchange factor). As shown in Figure 1A, Grh1-GFP colocalized substantially with Sec13-DsRed, and Grh1-DsRed colocalized substantially with Sec26-GFP, but Grh1-GFP was clearly displaced from Sec7-DsRed. The Grh1-labeled structures resembled the Sec13-labeled tER sites in being small and round, whereas the Sec26-labeled early Golgi elements were larger and more irregular in shape. These qualitative observations were verified by the quantitation shown in Figure 1B, where the yellow color represents overlapping pixels. Very little overlap was seen between Grh1-GFP and Sec7-DsRed (Figure 1B–3). About 70–80% of the Grh1-GFP overlapped with Sec13-DsRed, and vice versa (Figure 1B–1). Nearly all of the Grh1-DsRed overlapped with Sec26-GFP, but only about half of the Sec26-GFP overlapped with Grh1-DsRed because the Sec26-GFP-labeled structures were larger (Figure 1B–2). These results place Grh1 in a location encompassing the tER and early Golgi. In terms of size and shape, Grh1-labeled puncta most closely resembled Sec13-labeled puncta, implying that Grh1 is concentrated at or near tER sites in P. pastoris.

Figure 1. P. pastoris Grh1 substantially colocalizes with a tER marker.

(A) Top row: Grh1-GFP was imaged together with the tER marker Sec13-DsRed. Middle row: Grh1-DsRed was imaged together with the early Golgi marker Sec26-GFP. Bottom row: Grh1-GFP was imaged together with the late Golgi marker Sec7-DsRed. Scale bar, 2 μm. (B) The colocalization observed by fluorescence microscopy was quantified for the three comparisons shown in (A). The overlap between the red and green signals was measured for each of ~20 individual cells as described in Materials and Methods. Above the horizontal axis, yellow indicates the percentage of the red signal that overlapped with green pixels. Below the horizontal axis, yellow indicates the percentage of the green signal that overlapped with red pixels. Bars indicate s.e.m.

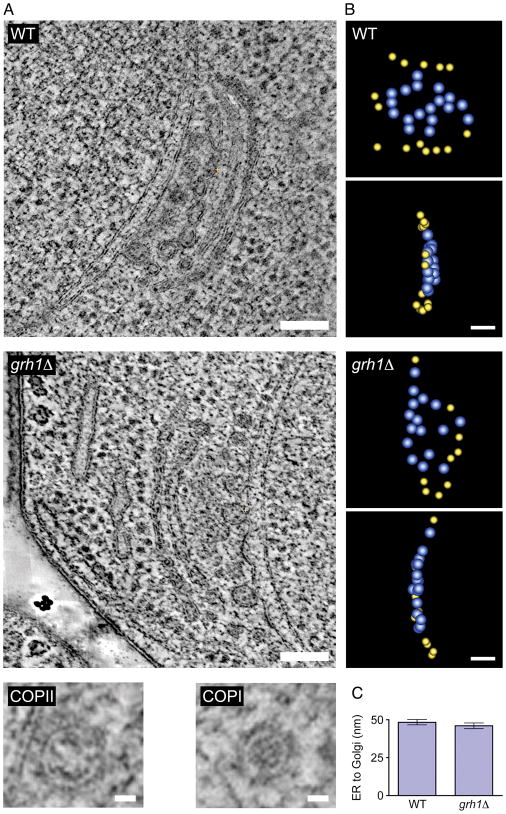

Figure 3. Deletion of P. pastoris Grh1 has no obvious effect on the morphology of tER-Golgi units.

(A) Two full tomographic reconstructions of nucleus-associated tER-Golgi units were performed for a wild-type strain, and two for a grh1Δ strain. Shown in the larger panels are representative slices from one tomographic reconstruction for each strain (see Supplementary Movies S1 and S2). The Golgi stacks contained 3–4 cisternae, not all of which are visible in each tomographic slice. Scale bars, 100 nm. The smaller panels show representative slices from tomographic reconstructions of presumptive COPII and COPI vesicles. Scale bars, 25 nm. (B) For the tomographic reconstructions shown in (A), presumptive budding and completed COPII vesicles were modeled as blue spheres and presumptive COPI vesicles were modeled as yellow spheres. Shown are top and side views of vesicles present at the tER-Golgi interface from the wild-type (WT) cell (upper two panels) or the grh1Δ cell (lower two panels). (C) The mean distance between the ER membrane and cis-Golgi cisternae was quantified by using ImageJ to analyze thin-section electron micrographs. For each tER-Golgi unit, the distance between the ER surface and the adjacent cis-Golgi cisterna was taken as the average of three values measured at the center and the two edges of the cisterna. These measurements were taken at flat tER regions that were not engaged in budding. The analysis was performed for 41 tER-Golgi units from wild-type cells and 35 tER-Golgi units from grh1Δ cells. Bars indicate s.e.m.

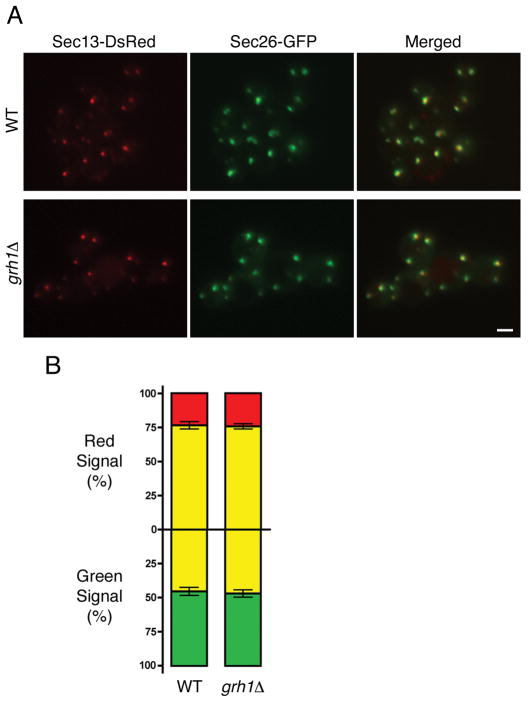

Figure 2. Deletion of P. pastoris Grh1 has no effect on the tER-Golgi association.

(A) Top row: the tER marker Sec13-DsRed was imaged together with the early Golgi marker Sec26-GFP in wild-type (WT) cells. Bottom row: same as the top row except with grh1Δ cells. (B) The overlap observed by fluorescence microscopy was quantified as in Fig. 1B. Bars indicate s.e.m.

Grh1 is dispensable for the organization of tER-Golgi units in P. pastoris

If Grh1 plays a structural role in the yeast secretory pathway, then based on our localization data, Grh1 should act at the tER-Golgi interface. For example, Grh1 might be needed to maintain the tight juxtaposition of tER sites with cis-Golgi cisternae in P. pastoris (32). To test this possibility, we deleted the GRH1 gene from P. pastoris and examined the mutant strain by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 2A). tER sites were marked with Sec13-DsRed, and early Golgi cistermae were marked with Sec26-GFP. As expected, these two markers were closely associated in wild-type cells. The same pattern was observed in grh1Δ cells. Quantitation indicated that the two markers overlapped to the same degree in wild-type and grh1Δ cells (Figure 2B).

To determine whether loss of Grh1 might have subtle effects on the structure of the tER-Golgi system, we employed electron tomography and thin-section electron microscopy. By electron tomography, a typical P. pastoris Golgi stack appears as 3–4 cisternae adjacent to a tER site (32). Tomographic reconstructions of two tER-Golgi units from a wild-type strain and two tER-Golgi units from a grh1Δ strain revealed no obvious differences in either the stacked structure of the Golgi or the tER-Golgi association (Figure 3A, large panels; Supplementary Movies 1 and 2). Quantitation of thin-section micrographs indicated that the average distance between the ER membrane and and cis-Golgi cisternae was ~50 nm and was not significantly different in wild-type and grh1Δ cells (Figure 3C). In both wild-type and grh1Δ strains, the region between the ER and the cis-Golgi was largely devoid of ribosomes but contained budding and completed vesicles, which were tentatively identified as COPII or COPI vesicles (Figure 3A, small panels) based on size, staining characteristics, and resemblance of the larger vesicles to budding profiles at the tER membrane (32). As shown in Figure 3B, a central cluster of presumptive COPII vesicles (blue) was typically flanked by presumptive COPI vesicles (yellow). These observations are consistent with a previous tomographic analysis (32). Thus, we find no evidence that Grh1 is essential in P. pastoris for Golgi stacking, tER-Golgi association, or vesicle accumulation at the tER-Golgi interface.

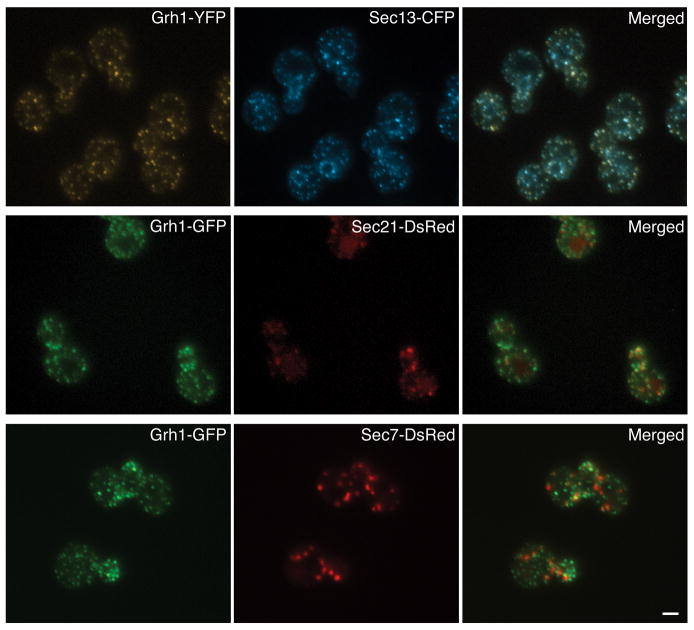

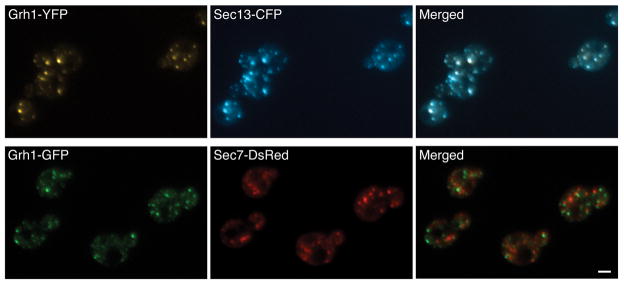

Grh1 colocalizes with COPII in S. cerevisiae

Can we also use S. cerevisiae to evaluate the location and possible structural role of Grh1? The dispersed tER-Golgi system in this yeast is sometimes advantageous because the different compartments of the secretory pathway can be readily distinguished. We found that S. cerevisiae Grh1-YFP colocalized extensively with the tER marker Sec13-CFP (Figure 4). By contrast, Grh1-GFP showed little overlap with the early Golgi marker Sec21-DsRed (a component of the COPI coat) or with the late Golgi marker Sec7-DsRed (Figure 4).

Figure 4. S. cerevisiae Grh1 substantially colocalizes with a tER marker.

Top row: Grh1-YFP was imaged together with the tER marker Sec13-CFP. Middle row: Grh1-GFP was imaged together with the early Golgi marker Sec21-DsRed. Bottom row: Grh1-GFP was imaged together with the late Golgi marker Sec7-DsRed. Scale bar, 2 μm.

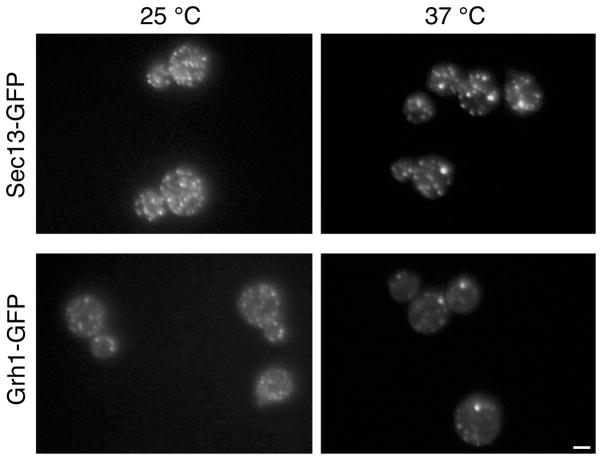

It has been reported that when thermosensitive sec12 mutants are incubated at 37°C, many of the COPII puncta coalesce into larger structures (38, 39). This effect is apparently a consequence of inhibiting ER export (Y. Liu, manuscript in preparation). We confirmed that a subset of the tER sites tagged with Sec13-GFP coalesced at 37°C in a thermosensitive sec12 mutant (Figure 5). Inhibiting ER export also caused the partial coalescence of Grh1-GFP puncta (Figure 5). The combined results support the conclusion that Grh1 is concentrated at or near tER sites in S. cerevisiae.

Figure 5. tER sites coalesce in a temperature-sensitive sec12 mutant of S. cerevisiae.

sec12-1 mutant cells were engineered by gene replacement to express a tER marker, either Sec13-GFP (top row) or Grh1-GFP (bottom row). These strains were grown at 25°C, and then either held at 25°C or shifted for 1 h to 37°C before imaging. Scale bar, 2 μm.

Glucose deprivation reveals a tER-Golgi association in S. cerevisiae in the presence or absence of Grh1

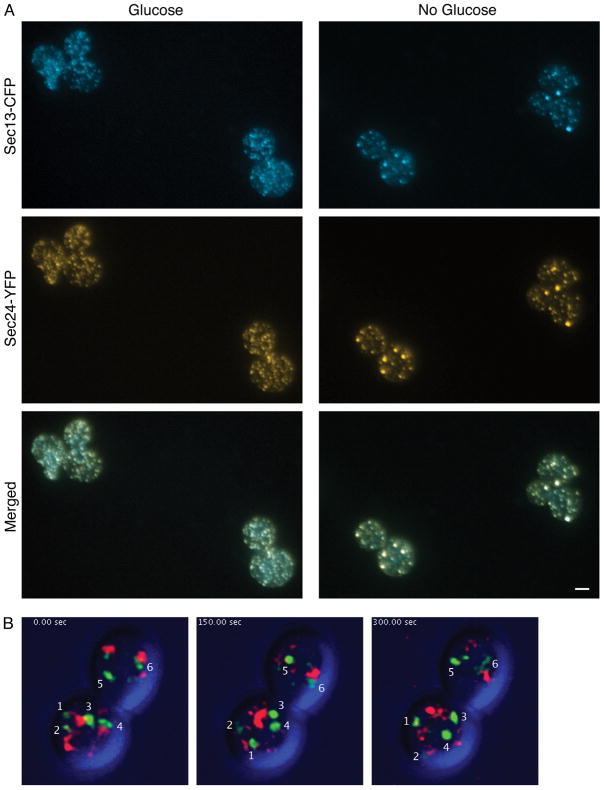

Because the coalescence of tER sites in S. cerevisiae simplifies the tER pattern, any juxtaposition of tER sites with the early Golgi should become more apparent. To facilitate this analysis, we sought a more convenient way to simplify the tER pattern. When S. cerevisiae cells were transferred from glucose-containing minimal medium to glucose-free minimal medium, many of the tER sites marked with Sec13-CFP coalesced within 10 min (Figure 6A). The same result was seen with Sec24-YFP, a second tER marker (Figure 6A). tER coalescence presumably resulted from inhibition of the secretory pathway. To test this interpretation, we assessed the activity of the secretory pathway by using 4D video microscopy to track Golgi cisternal maturation, which can be detected when individual cisternae lose a GFP-tagged early Golgi marker while acquiring a DsRed-tagged late Golgi marker (40). After transfer to glucose-free medium, most or all of the early Golgi cisternae retained the GFP-tagged marker for at least 5 min (Figure 6B; Supplementary Movie 3). By contrast, in glucose-containing medium, this early Golgi marker (GFP-Vrg4) has a mean half-time on the cisternae of only 2 min (40). Thus, glucose deprivation dramatically slowed cisternal maturation, confirming that glucose deprivation inhibits the secretory pathway.

Figure 6. tER sites coalesce in S. cerevisiae after the secretory pathway has been inhibited by glucose deprivation.

(A) Cells of a S. cerevisiae strain expressing the tER markers Sec13-CFP and Sec24-YFP was grown in minimal glucose medium, then centrifuged and resuspended in either glucose-containing minimal medium or glucose-free minimal medium, and finally incubated for 10 min before imaging. Scale bar, 2 μm. (B) Cells of a S. cerevisiae strain expressing the early Golgi marker GFP-Vrg4 and the late Golgi marker Sec7-DsRed were grown in minimal glucose medium, then centrifuged and resuspended in glucose-free minimal medium. After approximately 10 min, the glucose-deprived cells were imaged by 4D confocal microscopy to track the dynamics of Golgi cisternae (see Supplementary Movie S3). Shown are frames from the beginning, middle, and end of a representative 5-min movie. The fluorescence signals in the red and green channels were merged with scattered light images of the cell in the blue channel. The six early Golgi cisternae marked with numbers were tracked through the entire movie by examining the z-stack of images at each time point.

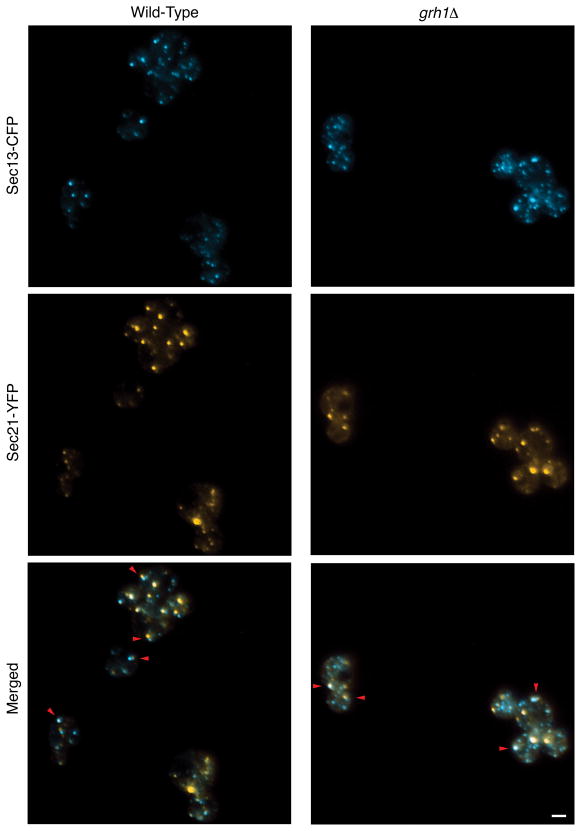

We used glucose deprivation of S. cerevisiae to look for a possible association between tER sites and cis-Golgi cisternae. Indeed, in glucose-deprived cells, many of the Sec13-CFP-labeled tER sites were clearly adjacent to Sec21-YFP-labeled early Golgi cisternae (Figure 7, left panels). A similar association could be seen by careful examination of rapidly growing cells, but the complexity of the fluorescence patterns obscured this effect (data not shown).

Figure 7. tER sites frequently associate with early Golgi cisternae in glucose-deprived wild-type and grh1Δ strains of S. cerevisiae.

Isogenic wild-type and grh1Δ strains were engineered to express the tER marker Sec13-CFP and the early Golgi marker Sec21-YFP. Cells were then imaged after transfer to glucose-free minimal medium, as in Figure 6. Red arrowheads indicate examples of close association between tER sites and early Golgi cisternae. Scale bar, 2 μm.

Glucose deprivation provided a means to test whether Grh1 is needed for the tER-Golgi association in S. cerevisiae. In a grh1Δ strain, glucose deprivation revealed an association between Sec13-CFP-labeled tER sites and Sec21-YFP-labeled early Golgi cisternae (Figure 7, right panels). These results were indistinguishable from those obtained with wild-type cells. Thus, we find no evidence that Grh1 is essential for the tER-Golgi association in S. cerevisiae.

Glucose-deprived S. cerevisiae cells have a less organized secretory pathway than P. pastoris cells

Glucose-deprived S. cerevisiae cells resemble P. pastoris cells in showing an association of tER and early Golgi markers. We therefore wondered whether glucose deprivation of S. cerevisiae enhances the organization on the entire secretory pathway. In glucose-deprived S. cerevisiae cells, Grh1-YFP colocalized with Sec13-CFP at enlarged tER sites, as expected (Figure 8). This observation is similar to results obtained with P. pastoris (see Figure 1A). But whereas Grh1-GFP and Sec7-DsRed were always closely juxtaposed in P. pastoris (see Figure 1A), the same markers showed no consistent juxtaposition in glucose-deprived S. cerevisiae cells (Figure 8). We conclude that S. cerevisiae resembles P. pastoris in displaying an association of Grh1-containing tER sites with the cis-Golgi, but differs from P. pastoris in lacking an association of trans-Golgi cisternae with earlier secretory compartments.

Figure 8. Grh1 associates with tER sites but not late Golgi cisternae in glucose-deprived S. cerevisiae cells.

The analysis was carried out as in Figure 4, except that cells were imaged after transfer to glucose-free minimal medium. Top row: Grh1-YFP was imaged together with Sec13-CFP. Bottom row: Grh1-GFP was imaged together with Sec7-DsRed. Scale bar, 2 μm.

Discussion

This study was motivated by the assumption that Grh1 shares a conserved basic function with GRASP proteins in other eukaryotes. Five lines of evidence support this idea. First, sequence analysis clearly identifies Grh1 as a member of the GRASP family (6, 17). Second, Grh1 forms a complex with Bug1, a coiled-coil protein that is structurally similar to GM130 (6, 36). Third, the membrane association of Grh1 requires N-terminal acetylation, which seems to play the same role as N-terminal myristoylation of GRASP65 (6). Fourth, recent publications demonstrate that like animal GRASPs, budding yeast Grh1 is important for unconventional secretion (41, 42). Fifth, our work confirms that like other GRASPs, Grh1 localizes to compartments of the secretory pathway (6).

On the other hand, Grh1 differs from the mammalian GRASPs in one respect: Grh1 has been shown to interact with proteins of the inner layer of the COPII vesicle coat (6, 34–36), which assembles at tER sites but not at the Golgi (43). This observation was seemingly at odds with a report that S. cerevisiae Grh1 colocalized with the cis-Golgi marker Rud3 (6). Therefore, we reexamined Grh1 localization. In our hands, Grh1 shows substantial colocalization with COPII at tER sites in both P. pastoris and S. cerevisiae, suggesting that Grh1-COPII interactions occur in vivo. We do not know why previous investigators saw Grh1 primarily at the cis-Golgi. However, a plausible explanation is that Grh1 cycles between early compartments of the secretory pathway, and that variations in strain background or experimental conditions can cause Grh1 to accumulate at either tER sites or the cis-Golgi. We speculate that in diverse eukaryotes, GRASP proteins act at the tER-Golgi interface. In support of this interpretation, Grh1 shows genetic interactions with trafficking proteins that operate at the tER-Golgi interface (6). Moreover, a portion of the mammalian GRASP65 molecules associate with an ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (44); the Drosophila GRASP homolog localizes to both tER sites and Golgi membranes (7); and GRASP homologs in Plasmodium falciparum are found next to the ER in a compartment that partially overlaps the cis-Golgi (18).

The localization data imply that if Grh1 has a structural role, its most likely site of action is the tER-Golgi interface. In P. pastoris, Golgi stacks are linked to tER sites by a ribosome-excluding “matrix” that contains COPII vesicles (32). We tested whether deletion of P. pastoris Grh1 would disrupt this matrix and perturb the organization of the tER-Golgi interface. As judged by electron tomography and thin-section electron microscopy, wild-type and grh1Δ strains showed no significant differences in tER-Golgi association or Golgi stacking. Genetic studies suggested a role for Grh1 in COPII vesicle tethering (6), and while our data do not exclude this possibility, tomographic reconstructions of tER-Golgi units from a wild-type and a grh1Δ strain revealed no obvious differences in vesicle accumulation at the tER-Golgi interface. We conclude that in P. pastoris, Grh1 does not play a major structural role in the secretory pathway.

This type of structural analysis is more difficult with S. cerevisiae due to the absence of Golgi stacking in wild-type cells. Certain mutant strains of S. cerevisiae accumulate stacked Golgi organelles (45–48), and in one such mutant, deletion of Grh1 had no effect on stacking (48). However, the Golgi structures in those S. cerevisiae mutants are probably exaggerated late Golgi compartments rather than ordered stacks of cis, medial, and trans cisternae (33), so those mutants may not be a useful model for Golgi stacking.

We therefore sought an alternative way to examine the structure of the early secretory pathway in S. cerevisiae. The key observation was that slowing ER export causes tER sites to coalesce, thereby simplifying the pattern observed by fluorescence microscopy. Coalescence of tER sites can be achieved within minutes by washing the cells into glucose-free medium. Under these conditions, early Golgi cisternae are often seen in close proximity to the enlarged tER sites. A tER-Golgi association had not previously been observed in S. cerevisiae by fluorescence microscopy, but is consistent with earlier results from electron microscopy (49) and from a yeast cell permeabilization assay (50). We found that deletion of S. cerevisiae Grh1 had no effect on the association of early Golgi cisternae with enlarged tER sites. The combined data indicate that in budding yeasts, Grh1 localizes to the tER-Golgi interface but is not required for the tER-Golgi association.

What then is the function of Grh1 and other GRASPs? Any model must account for the observation that PDZ domains are present in all GRASPs, including Grh1 (10, 16, 17). PDZ domains typically bind to the C-termini of target proteins (51), and the mammalian GRASPs have been shown to interact with the C-termini of several proteins (10, 23–25, 52). It therefore seems likely that Grh1 has a similar activity. More generally, GRASPs may facilitate the traffic of specific transmembrane proteins in the ER-Golgi system (24). This model could explain why GRASPs are important for unconventional secretion, because components of an unconventional secretion pathway might themselves traffic through the ER and Golgi (29). GRASPs probably also function in membrane tethering (4, 6, 52). In mammalian cells, GRASPs seem to have acquired an additional role in Golgi stacking (5, 12), suggesting that GRASPs are versatile proteins.

The work described here led to the discovery that glucose deprivation is a convenient means for arresting the secretory pathway in S. cerevisiae. Glucose deprivation presumably activates signal transduction pathways (53) that ultimately modify components at the tER and Golgi. It is particularly striking that glucose deprivation arrests cisternal maturation. The secretory pathway components affected by glucose deprivation are unknown, so an exploration of this effect may uncover novel regulators of Golgi dynamics.

This characterization of Grh1 also illustrates how a comparative analysis of P. pastoris and S. cerevisiae is a powerful way to study the secretory pathway. For example, the ordered tER-Golgi units of P. pastoris were useful for confirming that Grh1 is dispensable for secretory compartment organization, while the more fragmented secretory system of S. cerevisiae was useful for confirming that Grh1 associates with tER sites. At the same time, our data have revealed unexpected similarities between the two yeasts. We originally emphasized the differences between the tER-Golgi systems of P. pastoris and S. cerevisiae (33), but upon closer inspection, most of those differences seem to be superficial (30). For example, a mutant strain of P. pastoris has numerous small tER sites like those in S. cerevisiae (54), and we now find that slowing ER export in S. cerevisiae produces a tER pattern more like that in P. pastoris. These data suggest that tER sites in the two yeasts operate in a similar manner. Another unexpected finding is that cis-Golgi cisternae associate with tER sites not only in P. pastoris, but also in S. cerevisiae. Such an association of tER sites with a post-ER compartment may be a conserved feature of the secretory pathway. Even in mammalian cells, where peripherally located tER sites are distant from the Golgi (55), the peripheral tER sites are next to elements of a post-ER intermediate compartment (56). We speculate that association of tER sites with a post-ER compartment may be crucial for stabilizing tER sites. Although our investigation revealed that Grh1 does not mediate the tER-Golgi association in S. cerevisiae, we can use the same approach to test other components. Thus, S. cerevisiae is now available as a model system for studying a conserved structural feature of the secretory pathway.

Materials and Methods

General molecular biology methods

Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs or Fermentas. P. pastoris strains were derivatives of the his4 arg4 auxotroph PPY12 (57). S. cerevisiae strains were derivatives of the leu2 ura3 rme1 trp1 his4 strain JK9-3da (58), except for the sec12-1 temperature sensitive mutant strain LHY85 (sec12-1 ura3 his4 leu2 lys2 bar1), which was a gift of Linda Hicke. Yeast cells were grown and transformed as previously described (33).

Protein alignments and other sequence analyses were carried out using the Lasergene software package (DNASTAR). All plasmid constructs used in this study were documented electronically, and can be viewed in the Supplementary Information as a folder of GenBank-style annotated sequence files.

Plasmids and strains for P. pastoris

P. pastoris gene sequences were obtained from the ERGO database at Integrated Genomics (http://www.integratedgenomics.com).

Endogenous P. pastoris Grh1 was tagged with GFP or DsRed as follows. A 3′ portion of P. pastoris GRH1 plus approximately 500 downstream bases was amplified by PCR using the primers 5′-TTCGGTACCTTCGGTTTCCTGCATCGAATACCAGAGG-3′ and 5′-AAGTCTAGAAAGGATTACCAGAAAGAGGTTAC-3′. The amplified fragment was digested with KpnI and XbaI and ligated into pUC19-ARG4 (33) cut with the same enzymes. This plasmid was then mutagenized to replace the final four bases of GRH1 including the stop codon (TTAA) with a BamHI-NotI cassette (GGATCCTAGCGGCCGC). The resulting plasmid was digested with BamHI and NotI, and a fluorescent protein tag cassette was inserted as a BamHI-NotI fragment. One such tag cassette encoded mGFP, a monomeric version of EGFP carrying the A206K mutation (59), yielding pUC19-ARG4-PpGRH1-mGFP. A second tag cassette encoded six tandem copies of DsRed-Monomer (40), yielding pUC19-ARG4-PpGRH1-DsRed.M1×6. Both plasmids were linearized with BsaBI for transformation into an arg4 strain. Pop-in integrations were identified by screening for Arg+ cells with punctate fluorescence.

The following strategy was used to express Grh1-mGFP as a second copy in the presence of untagged endogenous Grh1. Genomic DNA from a pop-in strain carrying a chromosomal GRH1-mGFP fusion gene (see above) was subjected to PCR using the primers 5′-CTTCTTGAGCTCGTAACAATAAAAGAAAAAAACTAATC-3′ and 5′-CTTCTTACTAGTCATCTGATAAAAAACGTCCCGG-3′. The amplified fragment was digested with SacI and SpeI and ligated into the corresponding sites in pIB1 (60) to yield pIB1-PpGRH1-mGFP. This plasmid was digested with SalI for integration at the HIS4 locus. Integrations were identified by screening for His+ cells with punctate fluorescence, and were confirmed using PCR (60).

Sec7 was tagged with a hexa-DsRed.M1 cassette by pop-in gene replacement using the same general strategy described above for Grh1. The pop-in plasmid pUC19-ARG4(-XmnI)-PpSEC7-DsRed.M1×6 was linearized with XmnI for transformation into an arg4 strain. Sec26 was tagged with mGFP in a similar manner, except that the parental plasmid was pUC19-HIS4 (54). The plasmid pUC19-HIS4-PpSEC26-mGFP was linearized with KpnI for transformation into a his4 strain. Sec13 was tagged with DsRed using pUC19-ARG4-PpSEC13-Ds Red. M1 as previously described (54), or by a similar strategy using pUC19-KanMX-PpSEC13-DsRed.M1, which allows for selection on G418 plates (61).

The open reading frame of P. pastoris GRH1 was deleted as follows. 1-kb sequences flanking the GRH1 coding sequence were amplified from genomic DNA using the primers 5′-GTTGAATTCAAAGAGAGCTGTCATC-3′ and 5′-GTTTGTCCCGGGGCTGCTCCTGGTTAAAAAATCTC-3′ (upstream) or 5′-GTTTGTCCCGGGCCGGGACGTTTTTTATCAGATG-3′ and 5′-CACACCAAACCTCCTGCAGAGCAAC-3′ (downstream). The amplified fragments were digested with XmaI followed by either EcoRI (for the upstream fragment) or PstI (for the downstream fragment). These fragments were then inserted by a three-way ligation into pUC19 that had been digested with EcoRI and PstI. The resulting plasmid was cut with SmaI, and S. cerevisiae ARG4 was inserted as a HpaI fragment to generate pUC19-PpGRH1::ScARG4. Finally, a 4.3-kb EcoRI-PstI fragment was excised from this plasmid and transformed into PPY12 cells. Arg+ transformants were screened by PCR to confirm that GRH1 had been deleted.

Plasmids and strains for S. cerevisiae

Endogenous S. cerevisiae Grh1 was tagged with GFP or YFP as follows. A 3′ portion of S. cerevisiae GRH1 plus approximately 500 downstream bases was amplified by PCR using the primers 5′-CCTCCTGAATTCCCAACAGTAAAGCACTGTCCACAAC-3′ and 5′-CCTCCTTCTAGAGGTATTATATGAGCGGGTGCTTGTTGG-3′. The amplified fragment was digested with EcoRI and XbaI and cloned into YIplac211 (62) that had been digested with the same enzymes. This plasmid was then mutagenized to replace the final four bases of GRH1 including the stop codon (TTAA) with a BamHI-NotI cassette (GGATCCTAGCGGCCGC). The resulting plasmid was digested with BamHI and NotI, and a fluorescent protein tag cassette was inserted as a BamHI and NotI fragments. These tag cassettes encoded either mGFP or mYFP, yielding YIplac211-GRH1-mGFP or YIplac211-GRH1-mYFP, respectively. Both plasmids were linearized with KpnI for pop-in/pop-out gene replacement in a ura3 strain (33, 63).

Sec13 was tagged with either GFP or a triple-CFP cassette by pop-in/pop-out gene replacement using pUC19-URA3-SEC13-GFP (33) or pUC19-URA3-SEC13-CFPx3 (54), respectively, after linearization with BstEII. Sec24 was tagged with mYFP by pop-in/pop-out gene replacement using pUC19-URA3-SEC24-mYFP that had been linearized with BstEII. This plasmid was created in the same manner as the previously described pUC19-URA3-SEC24-GFP (33). Sec21 was tagged with a hexa-DsRed.M1 cassette (40) by pop-in/pop-out gene replacement using YIplac211-SEC21-DsRed.M1×6 that had been linearized with BclI. This plasmid was created in the same manner as the previously described YIplac211-SEC21-GFPx3 (64). Sec7 was tagged with YFP using pSSEC7-EYFP that had been linearized with SpeI. This plasmid was constructed in the same manner as the previously described pSSEC7-EGFPx3 (64). A DsRed-tagged version of Sec7 was overexpressed using YIplac204-TC-SEC7-DsRed.M1×6 that had been linearized with Bsu36I (40).

The open reading frame of S. cerevisiae GRH1 was deleted by amplifying the KanMX gene (61) using primers that included approximately 50 bases matching the GRH1 flanking sequences, then transforming cells and screening for G418 resistance (65). Candidate grh1Δ clones were confirmed by PCR.

Fluorescence microscopy

Cells were prepared for static imaging as follows. Cultures were grown overnight at 30°C in mimimal medium to mid-log phase. A 1-mL aliquot of the culture was centrifuged in a microfuge at 1800×g (5000 rpm) for 1 min. The supernatant was removed, and the cells were gently resuspended in 0.5 mL of the same medium either containing or lacking glucose. The centrifugation was repeated, and the cell were resuspended in 50 mL of medium either containing or lacking glucose. Approximately 10 min after this final resuspension, 1.5μL of the concentrated culture was spotted onto a glass slide and gently compressed with a coverslip. Single-plane widefield images were captured using an Axioplan 2 microscope (Zeiss) equipped with a 100X 1.4-NA Plan-Apo objective, appropriate filter sets for viewing the fluorescent proteins (Chroma), and a Hamamatsu ORCA-100 digital camera controlled by Axiovision software. The images were processed using MIN/MAX in Axiovision to remove background signal, and then were adjusted to optimize contrast and brightness using Adobe Photoshop.

Overlap between two differently labeled punctate compartments was quantified using the method of Zhao et al. (66). This method was implemented as follows. The red and green channels from a merged RGB image were separated in Photoshop, converted to grayscale, inverted to give dark spots on a light background, processed with the Despeckle filter, and saved as separate TIFF files. The TIFF file corresponding to the red channel was then opened in ImageJ (http://rsbweb.niov/ij/), and a binary thresholded image of black spots on a white background was created using the DynamicThreshold_1d plug-in (http://www.gcsca.net/IJ/Dynamic.html) with the parameters mask size=15, threshold=((max+min)/2)-C where C ranged from 7–10. The TIFF file was then inverted to give light spots on a dark background, and the binary thresholded image was subtracted, yielding a modified TIFF file that displayed only the punctate spots from the red channel. A similar procedure was used to generate a modified TIFF file displaying only the punctate spots from the green channel. The total signals from the red and green spots were then obtained using the Measure command in ImageJ. To determine the fraction of the punctate red signal that overlapped with the punctate green signal, the binary thresholded image from the green channel was subtracted from the TIFF file for the red channel. The resulting signal was measured, and was divided by the total signal previously measured for the red spots. A similar procedure was used to determine the fraction of the punctate green signal that overlapped with the punctate red signal.

Live-cell dual-color 4D confocal imaging was performed as previously described using a strain expressing GFP-Vrg4 as an early Golgi marker and Sec7-DsRed as a late Golgi marker (40), with the following modifications. Cells attached to the coverglass dish surface were washed and covered with minimal medium that either contained or lacked glucose. Image capture was performed using a Leica SP5 confocal microscope. GFP fluorescence was visualized using 488-nm excitation and 495–550 nm bandpass emission, and DsRed fluorescence was visualized using 561-nm excitation and 580–750 nm bandpass emission. The pixel size was 75 nm, the pinhole size was 1.2 Airy units, and the interval between optical sections was 0.3μm. Every 1.2 sec, 20 optical sections were captured to span the entire cell thickness. The red and green fluorescence images were processed by hybrid median filtering, deconvolution, and average projection, and were merged with blue images of the cells (37, 40).

Electron microscopy and tomography

A 100-mL P. pastoris culture of either wild-type (Grh1-GFP) or grh1Δ cells was grown in rich medium to mid-log phase at 30°C with shaking. The cells were then concentrated by vacuum filtration using a 0.22-μm filter (Millipore). A small amount of the cell paste was placed into the deeper side of 0.1/0.3 mm silver planchettes (Ted Pella). Planchettes were placed in a specimen holder and frozen in a Bal-Tec high-pressure freezer (RMC). The samples were immediately put into 0.25% glutaraldehyde, 0.1% uranyl acetate in anhydrous acetone, and were freeze substituted for five days at −80°C in a freeze-substitution device (Leica). Then the samples were warmed to −50°C for 1 h and washed three times with −50°C anhydrous acetone for 15 min per wash. Infiltration was performed overnight (~15 h) in 25% HM20 resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in anhydrous acetone. Samples were then subjected to successive overnight infiltrations at −50°C in HM20 at concentrations of 50%, 75%, and 100%, followed by three incubations of 1 h each with 100% HM20. Finally, the samples in HM20 were placed in molds under nitrogen gas at −50°C, and were polymerized with ultraviolet light for ~15 h before being warmed to room temperature.

Embedded samples were trimmed and sectioned using a microtome (Leica). Sections were cut at thicknesses of either 80 nm for thin-section analysis or 250–300 nm for tomography, post-stained for 8 min with 2% uranyl acetate in 70% methanol followed by 5 min in Reynold’s lead citrate, and washed three times for 1 min each with deionized H2O between and after post- staining. For tomography, fiducial markers were applied to both sides of the grid as follows. A grid was floated onto a 10-μl drop of 15-nm colloidal gold solution (British Biocell International) for 10 min. The grid was then washed with deionized H2O, and 15-nm colloidal gold was applied to the other side of the grid.

Images at 25,000X magnification were captured using an FEI Tecnai F30 scanning transmission electron microscope equipped with a Gatan Ultrascan camera. For tomography, data sets were collected using a Fischione Instruments model 2040 dual-axis tomography holder, and were processed using the IMOD software suite (http://bio3d.colorado.edu/imod/).

Supplementary Material

The two protein sequences were aligned using the ClustalW algorithm. Identical residues are shaded yellow.

The intervals between tomographic slices are 2.3 nm. A frame from this movie is shown in Figure 3A.

The intervals between tomographic slices are 1.8 nm. A frame from this movie is shown in Figure 3A.

Cells were transferred to glucose-free medium approximately 10 min before the movie was initiated. The green signal is from GFP-Vrg4, the red signal is from Sec7-DsRed, and the blue signal is from the budded cell. Three frames from this movie are shown in Figure 6B. Interestingly, the green structure at the upper right (labeled “6” in Figure 6B) remained consistently associated with a red structure, suggesting that glucose deprivation trapped a maturing cisterna that contained different domains.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 GM061156 and March of Dimes grant #1-FY07-465. Thanks to Laura Satkamp for providing constructs to label P. pastoris SEC7 and SEC26, to Nike Bharucha for providing pUC19-KanMX-PpSEC13-DsRed.M1, to Vytas Bindokas for help with fluorescence microscopy, and to members of the Glick lab for constructive feedback.

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

GenBank-style Sequences for the plasmids used in this study are available online as part of the supporting information.

Contributor Information

Stephanie K. Levi, Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, The University of Chicago, 920 East 58th Street, Chicago, IL 60637

Dibyendu Bhattacharyya, Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, The University of Chicago, 920 East 58th Street, Chicago, IL 60637.

Rita L. Strack, Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, The University of Chicago, 920 East 58th Street, Chicago, IL 60637

Jotham R. Austin, II, Biological Sciences Division, Office of Shared Research Facilities, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637.

Benjamin S. Glick, Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, The University of Chicago, 920 East 58th Street, Chicago, IL 60637.

References

- 1.Mowbrey K, Dacks JB. Evolution and diversity of the Golgi body. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3738–3745. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cluett EB, Brown WJ. Adhesion of Golgi cisternae by proteinaceous interactions: intercisternal bridges as putative adhesive structures. J Cell Sci. 1992;103:773–784. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.3.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barr FA, Puype M, Vandekerckhove J, Warren G. GRASP65, a protein involved in the stacking of Golgi cisternae. Cell. 1997;91:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramirez IB, Lowe M. Golgins and GRASPs: holding the Golgi together. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:770–779. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Seemann J, Pypaert M, Shorter J, Warren G. A direct role for GRASP65 as a mitotically regulated Golgi stacking factor. EMBO J. 2003;22:3279–3290. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behnia R, Barr FA, Flanagan JJ, Barlowe C, Munro S. The yeast orthologue of GRASP65 forms a complex with a coiled-coil protein that contributes to ER to Golgi traffic. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:255–261. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200607151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kondylis V, Spoorendonk KM, Rabouille C. dGRASP localization and function in the early exocytic pathway in Drosophila S2 cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4061–4072. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sütterlin C, Polishchuk R, Pecot M, Malhotra V. The Golgi-associated protein GRASP65 regulates spindle dynamics and is essential for cell division. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3211–3222. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-12-1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang D, Mar K, Warren G, Wang Y. Molecular mechanism of mitotic Golgi disassembly and reassembly revealed by a defined reconstitution assay. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6085–6094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707715200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barr FA, Nakamura N, Warren G. Mapping the interaction between GRASP65 and GM130, components of a protein complex involved in the stacking of Golgi cisternae. EMBO J. 1998;17:3258–3268. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shorter J, Watson R, Giannakou ME, Clarke M, Warren G, Barr FA. GRASP55, a second mammalian GRASP protein involved in the stacking of Golgi cisternae in a cell-free system. EMBO J. 1999;18:4949–4960. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.18.4949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiang Y, Wang Y. GRASP55 and GRASP65 play complementary and essential roles in Golgi cisternal stacking. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:237–251. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200907132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feinstein TN, Linstedt AD. GRASP55 regulates Golgi ribbon formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:2696–2707. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-11-1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jesch SA, Lewis TS, Ahn NG, Linstedt AD. Mitotic phosphorylation of Golgi reassembly stacking protein 55 by mitogen activated protein kinase ERK2. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1811–1817. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.6.1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sütterlin C, Lin C-Y, Feng Y, Ferris DK, Erikson RL, Malhotra V. Polo-like kinase is required for the fragmentation of pericentriolar Golgi stacks during mitosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9128–9132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161283998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Satoh A, Warren G. Mapping the functional domains of the Golgi stacking factor GRASP65. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4921–4928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412407200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kinseth MA, Anjard C, Fuller D, Guizzunti G, Loomis WF, Malhotra V. The Golgi associated protein GRASP is required for unconventional secretion during development. Cell. 2007:524–534. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Struck NS, Herrmann S, Langer C, Krueger A, Foth BJ, Engelberg K, Cabrera AL, Haase S, Treeck M, Marti M, Cowman AF, Spielmann T, Gilberger TW. Plasmodium falciparum possesses two GRASP proteins that are differentially targeted to the Golgi complex via a higher- and lower-eukaryote-like mechanism. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2123–2129. doi: 10.1242/jcs.021154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yelinek JT, He CY, Warren G. Ultrastructural study of Golgi duplication in Trypanosoma brucei. Traffic. 2009;10:300–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Staehelin LA, Moore I. The plant Golgi apparatus: structure, functional organization and trafficking mechanisms. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1995;46:261–288. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marra P, Salvatore L, Mironov A, Jr, Di CAmpli A, Di Tullio G, Trucco A, Beznoussenko G, Mironov A, De Matteis MA. The biogenesis of the Golgi ribbon: the roles of membrane input from the ER and of GM130. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:1595–1608. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-10-0886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puthenveedu MA, Bachert C, Puri S, Lanni F, Linstedt AD. GM130 and GRASP65-dependent lateral cisternal fusion allows uniform Golgi-enzyme distribution. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:238–248. doi: 10.1038/ncb1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barr FA, Preisinger C, Kopajtich R, Körner R. Golgi matrix proteins interact with p24 cargo receptors and aid their efficient retention in the Golgi apparatus. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:885–891. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Angelo G, Prencipe L, Iodice L, Beznoussenko G, Savarese M, Marra P, Di Tullio G, Martire G, De Matteis MA, Bonatti S. GRASP65 and GRASP55 sequentially promote the transport of C-terminal valine bearing cargoes to and through the Golgi complex. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34849–34860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.068403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuo A, Zhong C, Lane WS, Derynck R. Transmembrane transforming growth factor-α tethers to the PDZ domain-containing, Golgi membrane-associated protein p59/GRASP55. EMBO J. 2000;19:6427–6439. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Preisinger C, Körner R, Wind M, Lehmann WD, Kopajtich R, Barr FA. Plk1 docking to GRASP65 phosphorylated by Cdk1 suggests a mechanism for Golgi checkpoint signaling. EMBO J. 2005;24:753–765. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nickel W, Rabouille C. Mechanisms of regulated unconventional protein secretion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:148–155. doi: 10.1038/nrm2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schotman H, Karhinen L, Rabouille C. dGRASP-mediated noncanonical integrin secretion is required for Drosophila epithelial remodeling. Dev Cell. 2008;14:171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levi SK, Glick BS. GRASPing unconventional secretion. Cell. 2007;130:407–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papanikou E, Glick BS. The yeast Golgi apparatus: insights and mysteries. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3746–3751. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preuss D, Mulholland J, Franzusoff A, Segev N, Botstein D. Characterization of the Saccharomyces Golgi complex through the cell cycle by immunoelectron microscopy. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:789–803. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.7.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mogelsvang S, Gomez-Ospina N, Soderholm J, Glick BS, Staehelin LA. Tomographic evidence for continuous turnover of Golgi cisternae in Pichia pastoris. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:2277–2291. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossanese OW, Soderholm J, Bevis BJ, Sears IB, O’Connor J, Williamson EK, Glick BS. Golgi structure correlates with transitional endoplasmic reticulum organization in Pichia pastoris and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:69–81. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gavin AC, Aloy P, Grandi P, Krause R, Boesche M, Marzioch M, Rau C, Jensen LJ, Bastuck S, Dümpelfeld B, Edelmann A, Heurtier MA, Hoffman V, Hoefert C, Klein K, et al. Proteome survey reveals modularity of the yeast cell machinery. Nature. 2006;440:631–636. doi: 10.1038/nature04532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krogan NJ, Cagney G, Yu H, Zhong G, Guo X, Ignatchenko A, Li J, Pu S, Datta N, Tikuisis AP, Punna T, Peregrín-Alvarez JM, Shales M, Zhang X, Davey M, et al. Global landscape of protein complexes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2006;440:637–643. doi: 10.1038/nature04670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schuldiner M, Collins SR, Thompson NJ, Denic V, Bhamidipati A, Punna T, Ihmels J, Andrews B, Boone C, Greenblatt JF, Weissman JS, Krogan NJ. Exploration of the function and organization of the yeast early secretory pathway through an epistatic miniarray profile. Cell. 2005;123:507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bevis BJ, Hammond AT, Reinke CA, Glick BS. De novo formation of transitional ER sites and Golgi structures in Pichia pastoris. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:750–756. doi: 10.1038/ncb852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castillon GA, Watanabe R, Taylor M, Schwabe TM, Riezman H. Concentration of GPI-anchored proteins upon ER exit in yeast. Traffic. 2009;10:186–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shindiapina P, Barlowe C. Requirements for transitional endoplasmic reticulum (tER) site structure and function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2010 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-07-0605. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Losev E, Reinke CA, Jellen J, Strongin DE, Bevis BJ, Glick BS. Golgi maturation visualized in living yeast. Nature. 2006;22:1002–1006. doi: 10.1038/nature04717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duran JM, Anjard C, Stefan C, Loomis WF, Malhotra V. Unconventional secretion of Acb1 is mediated by autophagosomes. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:527–536. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manjithaya R, Anjard C, Loomis WF, Subramani S. Unconventional secretion of Pichia pastoris Acb1 is dependent on GRASP protein, peroxisomal functions, and autophagosome formation. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:537–546. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klumperman J. Transport between ER and Golgi. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:445–449. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marra P, Maffucci T, Daniele T, Di Tullio G, Ikehara Y, Chan EKL, Luini A, Beznoussenko G, Mironov A, De Matteis MA. The GM130 and GRASP65 Golgi proteins cycle through and define a subdomain of the intermediate compartment. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:1101–1113. doi: 10.1038/ncb1201-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Franzusoff A, Redding K, Crosby J, Fuller RS, Schekman R. Localization of components involved in protein transport and processing through the yeast Golgi apparatus. J Cell Biol. 1991;112:27–37. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jedd G, Mulholland J, Segev N. Two new Ypt GTPases are required for exit from the yeast trans-Golgi compartment. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:563–580. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.3.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Novick P, Ferro S, Schekman R. Order of events in the yeast secretory pathway. Cell. 1981;25:461–469. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weinberger A, Kamena F, Kama R, Spang A, Gerst JE. Control of Golgi morphology and function by Sed5 t-SNARE phosphorylation. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4918–4930. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-02-0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morin-Ganet M-N, Rambourg A, Deitz SB, Franzusoff A, Képès F. Morphogenesis and dynamics of the yeast Golgi apparatus. Traffic. 2000;1:56–68. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brickner JH, Blanchette JM, Sipos G, Fuller RS. The Tlg SNARE complex is required for TGN homotypic fusion. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:969–978. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hung AY, Sheng M. PDZ domains: structural modules for protein complex assembly. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5699–5702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bachert C, Linstedt AD. Dual anchoring of the GRASP membrane tether promotes trans pairing. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16294–16301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.116129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zaman S, Lippman SI, Zhao X, Broach JR. How Saccharomyces responds to nutrients. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:27–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Connerly PL, Esaki M, Montegna EA, Strongin DE, Levi S, Soderholm J, Glick BS. Sec16 is a determinant of transitional ER organization. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1439–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bannykh SI, Balch WE. Membrane dynamics at the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi interface. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1–4. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Appenzeller-Herzog C, Hauri HP. The ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC): in search of its identity and function. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2173–2183. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gould SJ, McCollum D, Spong AP, Heyman JA, Subramani S. Development of the yeast Pichia pastoris as a model organism for a genetic and molecular analysis of peroxisome assembly. Yeast. 1992;8:613–628. doi: 10.1002/yea.320080805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kunz J, Schneider U, Deuter-Reinhard M, Movva NR, Hall MN. Target of rapamycin in yeast, TOR2, is an essential phosphatidylinositol kinase homolog required for G1 progression. Cell. 1993;73:585–596. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90144-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zacharias DA, Violin JD, Newton AC, Tsien RY. Partitioning of lipid-modified monomeric GFPs into membrane microdomains of live cells. Science. 2002;296:913–916. doi: 10.1126/science.1068539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sears IB, O’Connor J, Rossanese OW, Glick BS. A versatile set of vectors for constitutive and regulated gene expression in Pichia pastoris. Yeast. 1998;14:783–790. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980615)14:8<783::AID-YEA272>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wach A. PCR-synthesis of marker cassettes with long flanking homology regions for gene disruptions in S. cerevisiae. Yeast. 1996;12:259–265. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19960315)12:3%3C259::AID-YEA901%3E3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gietz RD, Sugino A. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rothstein R. Targeting, disruption, replacement, and allele rescue: integrative DNA transformation in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:281–301. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rossanese OW, Reinke CA, Bevis BJ, Hammond AT, Sears IB, O’Connor J, Glick BS. A role for actin, Cdc1p and Myo2p in the inheritance of late Golgi elements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:47–61. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wach A, Brachat A, Pohlmann R, Philippsen P. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1994;10:1793–1808. doi: 10.1002/yea.320101310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao X, Lasell TK, Melançon P. Localization of large ADP-ribosylation factor-guanine nucleotide exchange factors to different Golgi compartments: evidence for distinct functions in protein traffic. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:119–133. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-08-0420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The two protein sequences were aligned using the ClustalW algorithm. Identical residues are shaded yellow.

The intervals between tomographic slices are 2.3 nm. A frame from this movie is shown in Figure 3A.

The intervals between tomographic slices are 1.8 nm. A frame from this movie is shown in Figure 3A.

Cells were transferred to glucose-free medium approximately 10 min before the movie was initiated. The green signal is from GFP-Vrg4, the red signal is from Sec7-DsRed, and the blue signal is from the budded cell. Three frames from this movie are shown in Figure 6B. Interestingly, the green structure at the upper right (labeled “6” in Figure 6B) remained consistently associated with a red structure, suggesting that glucose deprivation trapped a maturing cisterna that contained different domains.