Abstract

Objective To investigate whether substantive criticism in electronic letters to the editor, defined as a problem that could invalidate the research or reduce its reliability, is adequately addressed by the authors.

Design Cohort study.

Setting BMJ between October 2005 and September 2007.

Inclusion criteria Research papers generating substantive criticism in the rapid responses section on bmj.com.

Main outcome measures Severity of criticism (minor, moderate, or major) as judged by two editors and extent to which the criticism was addressed by authors (fully, partly, or not) as judged by two editors and the critics.

Results A substantive criticism was raised against 105 of 350 (30%, 95% confidence interval 25% to 35%) included research papers, and of these the authors had responded to 47 (45%, 35% to 54%). The severity of the criticism was the same in those papers as in the 58 without author replies (mean score 2.2 in both groups, P=0.72). For the 47 criticisms with replies, there was no relation between the severity of the criticism and the adequacy of the reply, neither as judged by the editors (P=0.88 and P=0.95, respectively) nor by the critics (P=0.83; response rate 85%). However, the critics were much more critical of the replies than the editors (average score 2.3 v 1.4, P<0.001).

Conclusions Authors are reluctant to respond to criticisms of their work, although they are not less likely to respond when criticisms are severe. Editors should ensure that authors take relevant criticism seriously and respond adequately to it.

Introduction

Letters to the editor are essential for the scientific debate. Most importantly, they may alert readers to limitations in research papers that have been overlooked by the authors, peer reviewers, and editors.1 2 However, little research has been done to elucidate whether letters fulfil this role and whether the authors respond adequately to criticism. We could not find any systematic research in this area.

Information in instructions to authors about the purpose, content, and structure of letters, and how authors should respond to criticism, is generally lacking. Most information specifies limits—on number of words, authors, references, tables, figures, and time since publication of the research report. Guidelines for editors are also sparse.3 4 5

We have noticed that when the criticism is serious, such as suggesting a fatal flaw, authors sometimes avoid addressing it in their reply and instead discuss minor issues, or they misrepresent their research or the criticism. It is not known how common evasive replies are or how often editors assess whether authors have addressed criticisms appropriately and honestly and ask for changes when this is not the case. We investigated whether authors responded adequately to substantive criticism after publication and whether the critics and the editors were satisfied with the replies.

Methods

Our objectives were to study whether substantive criticism in letters to the editor was adequately addressed by authors, and whether the replies were less adequate when the criticism was serious. We defined substantive criticism as a problem that could invalidate the research or reduce its reliability.

Selection of research papers

We sampled consecutive research papers in the BMJ, defined as those published in the section entitled “Research” (from January 2006) and in the section entitled “Papers” (in earlier issues). We did not include papers in the primary care section, as some of these are not research reports. We excluded narrative reviews, commentaries, case reports, and papers that were not reports of research; the Christmas issues, as these rarely contain traditional research papers; and a supplement issue in January 2007.

Our target sample size was 50 research papers with a substantive criticism published in the web based rapid responses section of the BMJ within three months after publication of the research in the print issue of the journal, and with a reply from the authors. We have experience from previous studies that sample sizes of this magnitude are sufficient for pilot studies, the aims of which are to describe major issues that can be subjected to future, more focused studies. Based on a pilot study of five issues of the BMJ, we estimated that we would need to include 375 papers, or about 125 weekly issues.

One observer (AL) screened the electronic version of the BMJ from October 2005 to September 2007. For all research papers, he accessed the rapid response section. Using the title and dates at the top of the webpage, he extracted the number of rapid responses and authors’ replies within our three month window. The rapid responses were then read from the top, and as soon as any potentially substantive criticism was identified all rapid responses were copied into a data file and relevant text was marked in yellow. Thereafter, any authors’ replies were copied into another data file. This approach was simple, but it worked. AL did not look at authors’ replies before the data transfer for substantive criticism had taken place.

A second observer (PCG) without access to the authors’ replies read all the highlighted criticisms and made a final judgment, selecting the most important substantive criticism the first time it was raised. He did not read the research papers when making these judgments. If he could not confirm that a criticism was substantive, the paper was excluded.

For comparison, we also selected those papers with rapid responses and a substantive criticism where the authors had not published any replies.

Editors’ assessments of severity of criticism and adequacy of authors’ replies

The selected papers were randomised according to the random numbers generator in Excel and two BMJ editors (TD and FG) evaluated independently the severity of the substantive criticism in the randomised order. The editors did not know which criticisms had authors’ replies and they were not provided with authors’ replies. Severity was rated as: 1, minor (would not be expected to detract much from the paper’s reliability); 2, moderate (might detract importantly from the paper’s reliability); and 3, major (might invalidate the paper).

The editors were then provided with the authors’ replies and judged independently whether the criticism had been adequately addressed by the authors. The editors were allowed, although not required, to read the research paper when making this judgment. The adequacy of the reply was rated as: 1, fully addressed (the authors accepted the criticism or explained convincingly that the concern was not relevant); 2, partly addressed (the authors replied but did not fully answer the criticism); and 3, not addressed.

Critics’ assessment of adequacy of authors’ replies

Using the same scale, the critics were asked to rate whether they believed their concerns had been addressed adequately by the authors. They were given a URL address to the paper and informed that the journal was carrying out research on the role of letters to the editor to study whether authors respond adequately to criticism of their work, and to suggest possible editorial improvements.

Data analyses

Using the Mann-Whitney U test we compared the two sets of papers, those with and without authors’ replies, for severity of the criticisms. For criticisms with replies, we used Spearman’s rank correlation to assess whether the replies were less adequate when the criticism was serious. In both cases we used the average score of the editors’ assessments in cases of disagreement. We used the F test for equality of variances for editors’ assessments, and χ2 tests for proportions.

Results

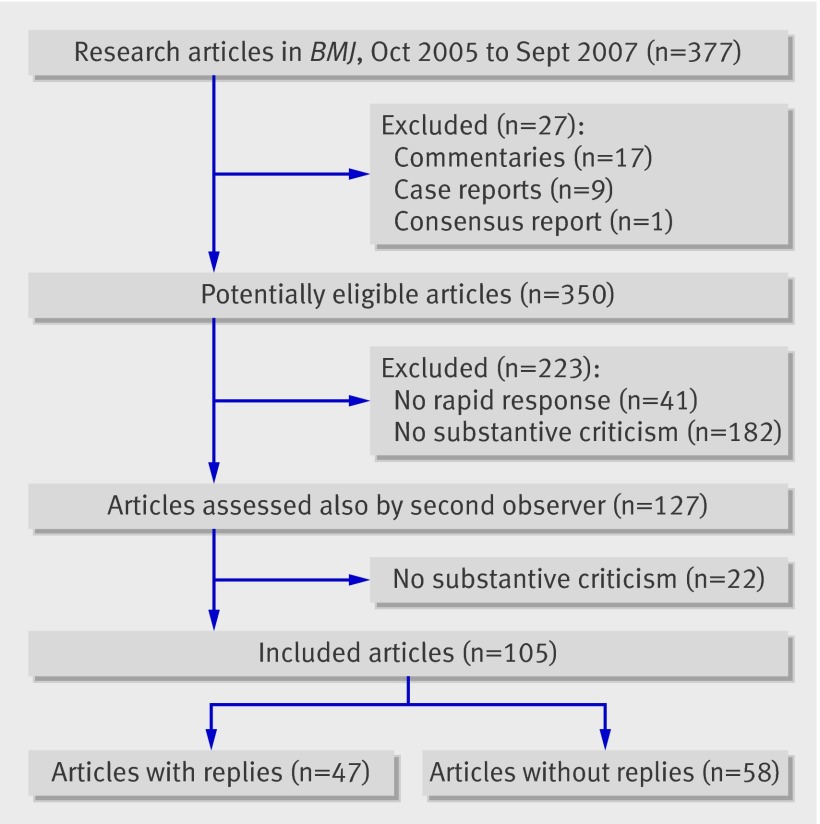

Overall, 27 of 377 identified articles were not research reports and were excluded. Of the remaining 350 articles, 223 were excluded: 41 because no rapid responses were received within three months and 182 because the responses clearly did not contain substantive criticism (figure). The second observer excluded an additional 22 papers without substantive criticism. Thus, rapid responses were available for 309 of the 350 research papers (88%) and substantive criticism was raised against 105 of the 350 papers (30%, 95% confidence interval 25% to 35%).

Flow of papers through study

The 105 included papers were reasonably representative of all research papers in the BMJ, as judged by the research design (table 1). However, substantive criticism was more often raised against randomised trials than against studies with mixed designs or with a variety of other designs (P=0.02 for test of similar distributions).

Table 1.

Study design of research papers with substantive criticisms in rapid responses section of electronic BMJ compared with other research papers published in BMJ

| Research design | No (%) of articles | |

|---|---|---|

| Substantive criticism in rapid responses (n=105) | Other articles (n=245) | |

| Randomised trial | 32 (31) | 59 (24) |

| Cohort study | 24 (23) | 50 (20) |

| Systematic review | 15 (14) | 41 (17) |

| Cross sectional study | 9 (9) | 37 (15) |

| Case-control study | 8 (8) | 4 (2) |

| Mixed design or other | 17 (16) | 54 (22) |

P=0.02 for test of similar distributions.

Both editors judged the severity of the criticism an average of 2.2 on the 1-3 scale, but one editor was more prone to use the moderate category than the other (P=0.002 for F test for equality of variances; table 2). This editor judged the criticism to be major (might invalidate the paper) in 34 cases (32%) compared with 54 cases (51%) for the other editor. Thus in the total sample of 350 papers, major criticism was raised against 10% of the papers according to one editor and against 15% according to the other.

Table 2.

Editors’ opinions of severity of criticism. Values are numbers (percentages)

| Severity of criticism* | Papers with authors’ replies (n=47)† | Papers without authors’ replies (n=58)† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Editor 1 | Editor 2 | Editor 1 | Editor 2 | ||

| Minor | 7 (15) | 13 (28) | 7 (12) | 16 (28) | |

| Moderate | 26 (55) | 10 (21) | 31 (53) | 12 (21) | |

| Major | 14 (30) | 24 (51) | 20 (34) | 30 (52) | |

F test for equality of variances for editors’ assessments: P=0.002.

*Scale from 1 (minor criticism) to 3 (major criticism).

†Mean score 2.2 for group with authors’ replies and 2.2 for group without authors’ replies (P=0.72).

Forty seven of the 105 papers with substantive criticisms (45%, 95% confidence interval 35% to 54%) had authors’ replies. The criticism was of the same severity in these papers as in the 58 without authors’ replies (mean score 2.2 in both groups, P=0.72). Furthermore, for the 47 criticisms with replies, there was no relation between the severity of criticism and the adequacy of the reply, neither as judged by the editors (P=0.88 and P=0.95, respectively) nor by the critics (P=0.83); opinions were obtained from 40 of the 47 critics (response rate 85%).

However, the editors and the critics judged the adequacy of the replies differently (table 3; P<0.001). The critics were much more critical of the replies than the editors, with average scores of 2.3 and 1.4, respectively, which is a pronounced difference on a three point scale. The two editors agreed in 36 cases, disagreed by one category in nine cases, and disagreed by two categories in two cases.

Table 3.

Editors’ and critics’ opinions of adequacy of authors’ replies in 40 cases. Values are numbers (percentages)

| Adequacy of replies to criticism* | Editor 1† | Editor 2† | Critics† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fully addressed | 29 (73) | 27 (68) | 6 (15) |

| Partly addressed | 7 (18) | 7 (18) | 16 (40) |

| Not addressed | 4 (10) | 6 (15) | 18 (45) |

*Scale from 1 (fully addressed) to 3 (not addressed).

†Mean rating 1.4 for editors and 2.3 for critics (P<0.001).

Discussion

Substantive criticism was raised against about one third of research papers in the BMJ over the two year period from October 2005 to September 2007. This may seem surprising, as the BMJ is a high impact factor general journal with an acceptance rate of submitted manuscripts that went down from 4% to 2% in the period we studied.6 However, this finding possibly reflects that it is easy to submit a rapid response and have it published in the BMJ, in contrast with most other journals that publish only a few selected letters in their print issues.7 As the perfect scientific study does not exist, we believe this type of post publication peer review is a valuable asset that other journals should consider implementing. A huge advantage of electronic publishing is that letters can appear the next day, whereas it usually takes months before letters become available in print journals. The drawback of the online response system is that some papers receive so much feedback that important criticism may be difficult to find.

Although we defined substantive criticism as a problem that could invalidate research or reduce its reliability, the authors responded to it in only about half of the cases. In contrast with what we had expected, the criticism was not more severe in those cases where the authors did not reply. Furthermore, for those criticisms that had replies, the replies were not less adequate when the criticism was severe.

It was also unexpected that editors differed noticeably from the critics in their assessment of the adequacy of authors’ replies. The editors were much more prone to accept a reply as being adequate than the critics. It is unclear who should be trusted. On the one hand, editors might be too positive, in a subconscious attempt to protect their own work and the journal’s prestige, whereas critics who bother to communicate their concerns might not be typical of the average reader and less likely to be satisfied whatever the replies. On the other hand, critics on average would be expected to be more knowledgeable about the subject and the methodological issues related to the research than the editors. The criticisms raised were generally appropriate, and the replies less so, and we therefore think that the critics’ assessments are likely to be closer to the truth than those of the editors. Criticisms were, on average, only partly addressed (table 3).

Limitations of the study

The web based rapid response facility in the BMJ makes it easy and quick to post criticisms, and practically all submitted letters are accepted. Many more letters are therefore published in the BMJ than in journals without online response systems: the mean and median number of responses for all 350 research papers in our study were 4.9 and 3, respectively, whereas a survey showed that the mean in print issues in 2007 was only 1.2 for BMJ, 1.0 for JAMA, 1.3 for Lancet, 2.1 for New England Journal of Medicine, and 0.6 for Annals of Internal Medicine.7 It is therefore not possible to extrapolate our results directly to other journals, although it is likely that important criticism could be raised equally often in other high impact journals, and probably much more often in other journals.

To investigate this further, we identified letters in the print version of the BMJ using PubMed and the BMJ website. We found that 20 of the 105 rapid responses with substantive criticism (19%) were also published in the print issue and five of these (25%) had a reply from the author in the print issue. The severity of the 20 criticisms in the print issue was similar to that of the 85 criticisms that were only published online (2.05 v 2.25, P=0.12). This is reassuring, although one might have expected the severity to be higher, as editors would generally select the harshest criticisms to give them the widest possible attention.

Our checks also showed that only one study had an author’s reply in the print version of the journal but no reply in the online rapid response section. In some cases, rapid responses are not posted in conjunction with the article itself on the BMJ website but in relation to commentaries or editorials describing the study. Our strategy for identifying studies could therefore have missed some criticisms and underestimated prevalence, although we judge the problem to be minor.

The corresponding author of every BMJ article receives an automated email when the paper is published and an automated reminder whenever a rapid response is posted. Authors are not told that responding is a requirement and not all rapid responses need a response. We, however, believe authors have an academic duty to respond to substantive criticism of their work and therefore cannot be excused because they were not asked to do so by an editor.

Implications for editors

Editors should encourage authors to respond adequately—for example, by making a contract between the author and journal on acceptance of the article, alerting authors to substantive criticisms, and highlighting substantive criticisms that have not been responded to adequately. Editors should post an editorial note if, despite requests for a proper response, the authors refuse to address criticism that could invalidate the paper or important parts of it. As editors may lack sufficient knowledge about the particular research area or the methods used, they should also consider sending substantive criticisms and authors’ replies for peer review, and it could be particularly valuable to use the critics as peer reviewers of authors’ replies. Finally, editors should consider not having time limits for letters that highlight important flaws.1 Science has no “use before” date but evolves through open debate. Editors of journals that do not have online response systems should consider introducing these to improve post publication peer review of their papers, as we found that only one fifth of rapid responses with substantive criticisms were published in the print journal.

Implications for readers

Readers should be aware that flaws in medical research are common and that the peer review system cannot ensure that flawed studies do not get published, even in the best journals. If a paper carries an important message, it is prudent to look for subsequent letters in the same journal and for commentaries in other journals. The journal Trials, for example, contributes to correcting the scientific record by welcoming submissions that discuss trials published elsewhere, and there is no time limit for such commentaries. Sometimes the flaws are so well hidden that it requires time consuming detective work to unravel them.8 9 10

As only a minor part of substantive criticism is published in the print version of a journal and as only these letters are indexed in PubMed, readers should also check out whether online responses have been posted to papers in journals with this possibility. Conversely, papers may seem more flawed than they really are, as relevant authors’ replies may have been only published online.

Implications for authors

Authors who consider quoting research papers should be careful. Flawed results and conclusions are often propagated in subsequent papers by authors who might have only read the abstract of the papers they quote, or even only the abstract’s conclusion.

What is already known on this topic

Letters to the editor about research papers serve a useful role as post publication peer review and for advancement of science

What this study adds

Substantive criticism was raised against a third of research papers published in the BMJ yet authors responded to the criticisms in only half of these cases

No relation was found between the severity of the criticism and the adequacy of the reply, neither as judged by the editors nor by the critics

The critics were much more critical of the replies than the editors

We thank the rapid respondents for their judgments and comments and Juliet Walker (BMJ), for administrative help.

Contributors: PCG conceived the idea, wrote the draft protocol and manuscript, and did the data analyses. He is guarantor. TD and FG commented on the protocol and evaluated the selected responses and replies. AL collected and screened the research papers and did a supplementary analysis of letters in the print issues. All authors contributed to the manuscript.

Funding: This study received no funding. The Nordic Cochrane Centre and BMJ provided in-house resources.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the unified competing interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that all authors had: (1) no financial support for the submitted work from anyone other than their employer; (2) no financial relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; (3) no spouses, partners, or children with relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; (4) TD and FG are editors of the BMJ.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: Data sharing: A full dataset is available at www.cochrane.dk/research/data_archive/2010_1. These data may only be used for replication of the analyses published in this paper or for private study. Express written permission must be sought from the authors for any other data use. Consent was not obtained from study participants, and we therefore needed to delete spontaneous comments and also the judgements made by the rapid responders. Researchers are welcome to contact us if they wish to know which specific criticisms we selected for the individual papers.

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;341:c3926

References

- 1.Altman DG. Poor-quality medical research: what can journals do? JAMA 2002;287:2765-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horton R. Postpublication criticism and the shaping of clinical knowledge. JAMA 2002;287:2843-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals: writing and editing for biomedical publication. 2008. www.icmje.org. [PubMed]

- 4.Council of Science Editors. Home page. 2009. www.councilscienceeditors.org.

- 5.World Association of Medical Editors. Home page. 2009. www.wame.org.

- 6.Godlee F. Research in the BMJ. BMJ 2007;335:0. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Von Elm E, Wandel S, Jüni P. The role of correspondence sections in post-publication peer review: a bibliometric study of general and internal medicine journals. Scientometrics 2009;81:747-55. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gøtzsche PC. Methodology and overt and hidden bias in reports of 196 double-blind trials of nonsteroidal, antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Controlled Clin Trials 1989;10:31-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansen HK, Gøtzsche PC. Problems in the design and reporting of trials of antifungal agents encountered during meta-analysis. JAMA 1999;282:1752-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirji KF. No short-cut in assessing trial quality: a case study. Trials 2009;10:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]