Abstract

We compared drug-related behaviors, including initiation of drug use, among street youth residing in two adjacent neighborhoods in Vancouver. One neighborhood, the Downtown Eastside (DTES), features a large open-air illicit drug market.

In multivariate analysis, having a primary illicit income source (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] = 2.64, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.16 – 6.02) and recent injection heroin use (AOR = 4.25, 95% CI: 1.26 – 14.29) were positively associated with DTES residence, while recent non-injection crystal methamphetamine use (AOR: 0.39, 95% CI: 0.16 – 0.94) was negatively associated with DTES residence. In univariate analysis, dealing drugs (Odds Ratio [OR] = 5.43, 95% CI: 1.24 – 23.82) was positively associated with initiating methamphetamine use in the DTS compared to the DTES.

These results demonstrate the importance of considering neighborhood variation when developing interventions aimed at reducing drug related harms among street-involved youth at various levels of street entrenchment.

Keywords: street youth, crystal methamphetamine, initiation, injection drug use, drug dealing

INTRODUCTION

Cities throughout the world are increasingly confronted with diverse health and social harms related to the use of illicit drugs (1–3). Commonly, these harms are most intense in areas where illicit drug markets are active (4–6), and studies have reported consistently high incidence of HIV and hepatitis C infection, incarceration, and fatal and non-fatal overdose among illicit drug-using individuals in urban centers that contain drug markets (7, 8). As a result, a variety of public health and law enforcement interventions have become clustered in urban illicit drug markets in an attempt to mitigate the negative impacts of illicit drug use and drug market involvement (9, 10).

Recent efforts to disentangle urban health harms have focused on how environmental phenomena help to define the risk environments experienced by vulnerable populations in specific geographic areas (11, 12). For example, researchers using spatial analysis in Kwazulu-Natal found that in a mixed urban-rural study setting, residency near the National Road, a major regional transit hub, was associated with a significantly higher risk of HIV infection (13). In the context of illicit drug use, research from Vancouver recently identified residency in the city’s downtown eastside (DTES), a low-income neighborhood that hosts one of North America’s largest open-air illicit drug markets, as independently associated with a twofold risk of HIV seroconversion among a cohort of injection drug users, despite adjustment for a variety of confounders (14). Further, researchers have demonstrated that geographic proximity to an illicit drug market, as well as neighborhood-level factors, help determine the severity and scope of drug- and health-related risks that illicit drug users may face (15–17).

‘Entrenchment’ in this context refers to individuals that have become highly acculturated to life on the street, who employ street-based income generation activities (e.g., selling drugs, sex trade involvement, panhandling) as a primary source of income, and who report long-term homelessness or living in unstable housing situations (e.g., single-occupancy hotels or shelters) (18). Preventing illicit drug scene entrenchment is critical to the reduction of a variety of severe health risks, and experts have therefore urged a greater focus on research into the prevention of injection drug use initiation (19). Street youth are at particularly high risk of drug scene entrenchment and related risk behaviors such as the initiation of injection drug use (20), and exposure to an adult illicit drug injection scene has previously been shown to be associated with a variety of health harms among this population (4, 21).

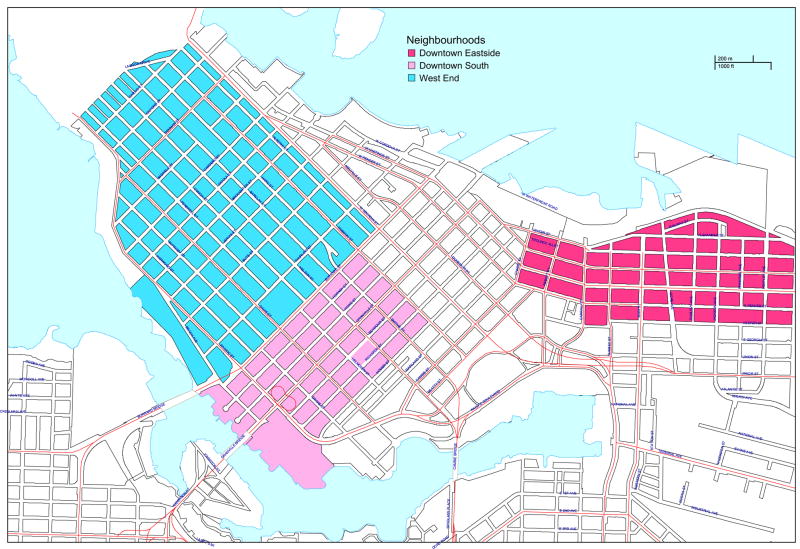

Recent qualitative and ethnographic research conducted among a cohort of street youth in Vancouver suggests that a number of social and structural dynamics play a key role in increasing young people’s entrenchment in Vancouver’s local drug scene (22–24). Further, these dynamics shape risk differently in the DTES compared with an adjacent area known as the Downtown South (DTS), which is Vancouver’s primary entertainment and retail district, and also features urban residential and financial zones (25). The DTS is characterized by mixed income housing, including an estimated 1,000 non-market housing units (25), and a more ‘closed’ drug scene than that found in the DTES, featuring younger individuals and those characterized by less intense involvement in street life (i.e., illicit income generation, long-term homelessness, and drug dependence) (23). The DTS is also adjacent to the West End, an affluent retail and residential district that youth in our setting often consider as an extension of the DTS (see Figure 1) (24). Previous research also suggests that illicit drug users in the DTS are younger, less-entrenched, and use crystal methamphetamine at higher rates compared with drug users in other neighbourhoods in Vancouver (26). Comparatively, the DTES is well-known as an open-air adult injecting scene, characterized by a large proportion of individuals that engage in high levels of crack use, injection heroin and cocaine use, illicit income generation, and who report high levels of unstable housing and homelessness (23). Compared with the British Columbia provincial average, the DTES also has a 33% increased mortality rate, and a higher proportion of male and Aboriginal residents. Further, life expectancy is 3 years lower than the provincial average among female DTES residents, and 9 years lower than the provincial average among male DTES residents (5). Drug-related deaths (i.e. overdose mortality) occur at 7 times the provincial rate in the DTES (5), and while rates of drug overdose have decreased in recent years, this phenomenon still represents one of the major leading causes of death in British Columbia (27, 28).

Fig. 1.

Map of neighbourhoods.

Locally, concern exists that the proximity of the DTS to the DTES, coupled with the mobility of the city’s street youth population across these distinct neighborhoods, may contribute to a process of normalization of more intense drug-related harms (21). This process of normalization could in turn lead to increased uptake of injection drug use and higher levels of street entrenchment among youth residing in both areas (in spite of the fact that open injection drug use is far less prevalent in the DTS than in the DTES) (29). This concern is informed by research investigating the association between neighborhood-level influences and drug-related health risks (14, 16, 24, 30, 31). In particular, a large body of literature has demonstrated that the built environment affects the range of choices available to vulnerable populations such as street-involved youth (32–36), particularly when considered within the context of the confluence of other social, structural, and policy factors within a broader risk environment (2, 37). Appropriate and stable housing, for example, is often not available to street-involved youth and may result in a reliance on social networks for stability (23). As such, the influence of these social networks may play a primary role in shaping decision-making among this population (22).

The scope and density of the illicit drug market in Vancouver’s DTES, as well as the presence of a large street youth population spread out across multiple neighborhoods, affords a unique opportunity to investigate how exposure to an adult drug market may shape risk among street youth. We therefore sought to further quantify the health, behavioral and drug-related risks experienced by street youth residing in the DTES and the DTS neighborhoods in Vancouver, and to investigate geographic correlates of drug use initiation (i.e., crystal methamphetamine use) and drug market involvement among a street youth sample.

METHODS

All data for these analyses were conducted using data from the At-Risk Youth Study (ARYS), a Vancouver-based cohort study of street youth aged 14 to 26 (38). ARYS participants are recruited using street outreach and self-referral, and eligible study participants reported using illicit drugs other than marijuana in the last 30 days. Once recruited, participants complete an interviewer-administered questionnaire and a physical and mental health assessment that includes blood samples for diagnostic testing. Thereafter, participants return to complete the interviewer-administered questionnaire semi-annually. Participants are provided with a $20 CND honorarium. The ARYS questionnaire solicits detailed demographic data as well as data on drug use behaviors, income sources, housing situation, experiences with incarceration, involvement in the sex trade and the illicit drug trade, and perceptions of the efficacy and accessibility of health and social services. The study has been approved by the University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care Ethics Review Board, and all study participants provide written consent prior to enrolment.

For the present study, data were collected from participant interviews conducted between September 1, 2005 and December 31, 2007. Because we were interested in comparing drug-related behaviors and health risks among street youth in two well characterized neighborhoods (those in the DTES with those in the DTS), we restricted our sample to ARYS participants who reported currently residing in either of these two areas, and residency in the DTES vs. the DTS constituted our dependent dichotomous variable of interest. Our selection of independent variables of interest was informed by previous qualitative and quantitative analyses of illicit drug use conducted among vulnerable populations in our study setting (23, 38–40), and included the following: age, gender, ethnicity (Aboriginal vs. other), homelessness, amount of money spent on drugs per day ($50 or less vs. more than $50), having a primarily licit vs. illicit source of income, dealing drugs, recent crack smoking, recent non-injection crystal methamphetamine use, recent injection heroin use, recent injection cocaine use, recent injection crystal methamphetamine use, preferred location of illicit drug purchases (DTES vs. DTS vs. all other areas), unsafe sex (i.e., unprotected vaginal or anal sexual intercourse excluding commercial sex work), involvement in the commercial sex trade, having been assaulted, and being stopped, searched or detained by police. All behavioral variables refer to the 6 months prior to the participant interview. The variables selected for inclusion in the model represent commonly used identifiers of drug-related health harms, unstable housing situations, and involvement in street-based drug market scenes. Our statistical model therefore allows for the investigation of levels of health risks and street entrenchment among participants residing in each neighbourhood of interest.

We conducted univariate logistic regression analyses to determine factors associated with current neighborhood of residence (DTES vs. DTS). Categorical and explanatory variables were analyzed using Pearson’s X2, while continuous variables found to be normally distributed were analyzed using t-tests for independent samples, and continuous variables found to be skewed were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U tests. Variables found to be associated with the outcome of interest at p ≤ 0.05 were then considered in a fixed multivariate logistic regression model. Finally, we solicited data on circumstances surrounding first injection drug use and first crystal methamphetamine use experiences among study participants residing in the DTES or the DTS. We then conducted separate univariate logistic regression subanalyses to determine factors associated with the initiation of crystal methamphetamine among our cohort participants. In this subanalysis, participants were asked, “the first time you used crystal meth, what neighbourhood were you in?” All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Overall, 222 street youth participated in the present study, including 65 (29.3%) women and 51 (23.0%) individuals who self-identified as Aboriginal. Median participant age was 23.6 years old (Interquartile Range: 20.1 – 27.1). Overall, 155 (69.8%) participants reported currently residing in the DTS, while 67 (30.2%) reported currently residing in the DTES. Further, 26 (38.8%) of those participants residing in the DTES reported injection drug use in the last 6 months, while 37 (23.8%) of those residing in the DTS reported such use in the last 6 months. Drug dealing among street youth occurred at comparably high levels among participants in both neighborhoods (DTS: 74.8%; DTES: 85.1%; p = 0.091).

Tables 1 and 2 present the results of our univariate analyses of sociodemographic, behavioral, and drug use variables associated with current neighborhood of residence. Table 3 presents the results of the multivariate analysis and, as can be seen, after intensive adjustment for potential confounders, reporting an illicit primary income source (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] = 2.64, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.16 – 6.02, p = 0.021), injection heroin use (AOR = 4.25, 95% CI: 1.26 – 14.29, p = 0.019), and preferring to buy drugs in the DTES vs. the DTS (AOR = 6.93, 95% CI: 3.83 – 12.52, p < 0.001) were all independently associated with residence in the DTES. Further, non-injection crystal methamphetamine use (AOR = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.16 – 0.94, p = 0.037) was negatively associated with residing in the DTES.

Table I.

Univariate analysis of sociodemographic and behavioural factors associated with neighbourhood of residence among street youth in Vancouver (n = 222)

| Characteristic | Downtown South | Downtown Eastside | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 155 | n = 67 | |||

| Age | ||||

| Median (and IQR) | 23.2 (19.6–26.8) | 24.1 (21.3–27.0) | 1.25 (1.10 – 1.42) | 0.001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 114 (73.5) | 43 (64.2) | ||

| Female | 41 (26.5) | 24 (35.8) | 1.55 (0.84 – 2.87) | 0.161 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Other | 128 (82.6) | 43 (64.2) | ||

| Aboriginal | 27 (17.4) | 24 (35.8) | 2.65 (1.38 – 5.07) | 0.003 |

| Homelessness | ||||

| No | 21 (13.5) | 16 (23.9) | ||

| Yes | 134 (86.5) | 51 (76.1) | 0.50 (0.24 – 1.03) | 0.061 |

| Income source | ||||

| Primarily licit | 82 (52.9) | 22 (32.8) | ||

| Primarily illicit | 73 (47.1) | 45 (67.2) | 2.30 (1.26 – 4.19) | 0.007 |

| Unsafe sex | ||||

| No | 33 (21.3) | 16 (23.9) | ||

| Yes | 122 (78.7) | 51 (76.1) | 0.86 (0.44 – 1.70) | 0.669 |

| Involvement in the sex trade | ||||

| No | 139 (89.7) | 62 (92.5) | ||

| Yes | 16 (10.3) | 5 (7.5) | 0.70 (0.25 – 2.00) | 0.506 |

| Having been assaulted | ||||

| No | 83 (53.5) | 40 (59.7) | ||

| Yes | 72 (46.5) | 27 (40.3) | 0.79 (0.44 – 1.39) | 0.398 |

| Jacked up by Police* | ||||

| No | 107 (69.0) | 39 (58.2) | ||

| Yes | 48 (31.0) | 28 (41.8) | 1.60 (0.89 – 2.90) | 0.120 |

Note: CI = Confidence Interval; IQR = interquartile range.

Note: All behaviours refer to the previous six months.

‘Jacked up by police’ is defined as being stopped, searched or detained by police.

Table II.

Univariate analysis of drug use behaviors associated with neighborhood of residence among street youth in Vancouver (n = 222)

| Characteristic | Downtown South | Downtown Eastside | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 155 | n = 67 | |||

| Amount spent on drugs | ||||

| ≤ $50 per day | 76 (49.0) | 23 (34.3) | ||

| > $50 per day | 79 (51.0) | 44 (65.7) | 1.84 (1.02 – 3.34) | 0.044 |

| Dealing Drugs | ||||

| No | 39 (25.2) | 10 (14.9) | ||

| Yes | 116 (74.8) | 57 (85.1) | 1.92 (0.89 – 4.11) | 0.095 |

| Crack Use | ||||

| No | 66 (42.6) | 19 (28.4) | ||

| Yes | 89 (57.4) | 48 (71.6) | 1.87 (1.01 – 3.48) | 0.047 |

| Non-injection CM use | ||||

| No | 81 (52.3) | 52 (77.6) | ||

| Yes | 74 (47.7) | 15 (22.4) | 0.32 (0.16 – 0.61) | 0.001 |

| Injection heroin use | ||||

| No | 135 (87.1) | 47 (70.1) | ||

| Yes | 20 (12.9) | 20 (29.9) | 2.87 (1.42 – 5.80) | 0.003 |

| Injection cocaine use | ||||

| No | 143 (92.3) | 55 (82.1) | ||

| Yes | 12 (7.7) | 12 (17.9) | 2.60 (1.10 – 6.14) | 0.029 |

| Injection CM use | ||||

| No | 129 (83.2) | 58 (86.6) | ||

| Yes | 26 (16.8) | 9 13.4) | 0.77 (0.34 – 1.75) | 0.531 |

| Location of drug purchase | ||||

| DTS | 23 (14.8) | 48 (48) | ||

| DTES | 80 (51.6) | 3 (4.5) | 7.20 (4.24 – 12.25) | < 0.001 |

| Other | 52 (33.5) | 16 (23.9) | ||

Note: CI = Confidence Interval; CM = crystal methamphetamine.

Note: All behaviors refer to the previous six months.

Table III.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors associated with residence in the DTES vs. the DTS neighborhood among a cohort of street youth in Vancouver (n = 222)

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Per year older | 1.17 | (0.98 – 1.40) | 0.080 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Other | 1.00 | ---- | ---- |

| Aboriginal | 2.06 | (0.80 – 5.29) | 0.132 |

| Amount spent on drugs | |||

| ≤ $50 per day | 1.00 | ---- | ---- |

| > $50 per day | 0.77 | (0.33 – 1.79) | 0.546 |

| Income source | |||

| Primarily licit | 1.00 | ---- | ---- |

| Primarily illicit | 2.64 | (1.16 – 6.02) | 0.021 |

| Crack smoking | |||

| No | 1.00 | ---- | ---- |

| Yes | 1.05 | (0.43 – 2.57) | 0.923 |

| Non-injection CM use | |||

| No | 1.00 | ---- | ---- |

| Yes | 0.39 | (0.16 – 0.94) | 0.037 |

| Injection heroin use | |||

| No | 1.00 | ---- | ---- |

| Yes | 4.25 | (1.26 – 14.29) | 0.019 |

| Injection cocaine use | |||

| No | 1.00 | ---- | ---- |

| Yes | 0.95 | (0.23 – 4.03) | 0.948 |

| Preferred location of drug purchase | |||

| DTS | 1.00 | ---- | ---- |

| DTES | 6.93 | (3.83 – 12.52) | < 0.001 |

Note: DTES = downtown eastside; DTS = downtown south; CI = Confidence Interval

Note: All behaviors refer to the previous 6 months

Overall, 64 (28.8%) participants reported previously initiating injection drug use. Of these, 10 (24.4%) participants reported first injecting drugs in the DTES, while 20 (48.8%) reported first injecting drugs in the DTS. Further, among 72 (32.4%) participants who reported initiating crystal methamphetamine use, 43 (59.7%) reported initiating crystal methamphetamine use in the DTS, while 12 (16.7%) reported doing so in the DTES.

Finally, in a univariate logistic regression subanalysis, reporting initiating of methamphetamine use in the DTS compared with the DTES was significantly associated with reporting dealing drugs (OR = 5.43, 95% CI: 1.24 – 23.82, p = 0.030).

DISCUSSION

Among a cohort of street youth, levels of initiation of injection drug use were over twice as high in the DTS than levels reported by youth residing in the DTES. We also found that study participants residing in the DTES were significantly more likely to report having an illicit primary income source, report engaging in injection heroin use, and report preferring to buy drugs in the DTES compared with participants residing in the DTS. However, study participants living in the DTS were significantly more likely to engage in non-injection crystal methamphetamine use. Of concern, study participants reported initiating injection drug use in the DTS at a level twice as high compared with the DTES, and the initiation of crystal methamphetamine use was reported among study participants in the DTS at a level almost four times as high as the level of initiation reported in the DTES. Finally, in univariate analysis, individuals reporting initiating methamphetamine use in the DTS were more likely to report dealing drugs than those that reported initiating methamphetamine use in the DTES.

While preliminary, these results are surprising since we expected that residency within the DTES, which includes a large open-air illicit drug market, would be associated with substantially greater drug-related health risks. That we observed non-significant risks for a variety of types of drug use as well as for involvement in drug dealing and the sex trade between street youth residing in the DTS and the DTES may suggest that interventions to reduce youth entrenchment in an open-air illicit drug market should take into consideration the role of adjacent neighborhood street scenes in influencing drug use patterns (21). Specifically, while we found that participants residing in the DTES were more likely than those in the DTS to report having a primary illicit income source, we found no significant differences in risk of drug dealing, as well as comparably high levels of this illicit activity, among individuals residing in both neighborhoods. These reported high levels are consistent with previous research in our study setting, which found that 79% of a sample of street-involved youth reported selling drugs, while 86% reported that they were involved in the drug trade in order to generate income for their personal drug use (40). It is also of note that in univariate analysis, drug dealing was associated with reporting initiating crystal methamphetamine use in the DTS. While caution is warranted in the interpretation of univariate results, these data may suggest that the initiation of crystal methamphetamine by youth residing in the DTS signals an immersion into a street-based illicit drug scene, and may therefore represent a potential interventional point for the prevention of street entrenchment among youth. Taken alongside the findings of our multivariate analysis and previous qualitative work from our study setting, these results suggest that the DTS may be an introductory area for those youth drawn towards street-involvement and may uniquely facilitate transitions to the development of more intense risk behaviors as observed among youth in the DTES (21). This phenomenon may also be a product of the socio-historical context of drug use, illicit drug culture, and policy responses in the city of Vancouver. Beginning in the 1950s, the DTES began to transform from Vancouver’s premier retail, administration, and entertainment district into an area now better known as a low-income setting marked by high levels of injection drug use (41). This characterization has continued for decades, and has resulted in a commonly held perception of the DTES as a ‘closed’ space (23). While the results of our study are limited, it is possible that this perception of the DTES may discourage novice street-involved youth from initially residing in that area (23). For example, previous research in our study setting has hypothesized that non-injection crystal methamphetamine use may be predictive of the initiation of injection drug use among street youth (38), and as noted above we found that study participants initiated crystal methamphetamine use at much higher levels in the DTS compared with the DTES. While the DTES is the site of a variety of programs servicing that neighborhood’s large polydrug-using community, the street youth population in the DTS may contain a high number of individuals who are newly-recruited to street involvement and highly vulnerable to street entrenchment and initiation of injection drug use (21). This is particularly pertinent given that public health experts have suggested prioritizing the prevention of injection drug use among vulnerable populations (19).

These preliminary results build on previous research on geographic factors associated with drug market entrenchment and suggest areas of future research. Observers have noted the ways in which geographic migration can modify health risks among vulnerable populations in a variety of settings (42–44). While this research is often focused regionally, our findings suggest that considering micro-setting and intra-city migration may also be useful in identifying key opportunities for the reduction of risk for HIV and other blood-borne disease infection, the initiation of injection drug use, and street entrenchment. For example, the sexual transmission of HIV infection in southern Africa has been linked to the migration of laborers and the expansion of commercial sex trade work along the transit routes connecting South Africa to its neighboring countries (44, 45). As a result, policymakers have therefore targeted these particular transit routes for preventive campaigns to reduce sexual transmission of HIV (46).

While little data exist regarding migration patterns among street-involved youth in Vancouver, a previous qualitative study reported that the majority of youth participants migrated from other Canadian cities in order to escape negative situations with law enforcement, while a minority indicated that they grew up ‘on the streets’ of Vancouver’s downtown (23). In our study setting, like many other urban communities, street involvement appears to facilitate a range of high-risk behaviors among youth. Perhaps most relevant is our finding that participants report initiating crystal methamphetamine use at much higher levels in the DTS compared with the DTES. In this context, it is important to note that the DTS’ geographic proximity to the DTES and the mobility of street youth across these two areas appears to create a permeability that may facilitate further street entrenchment among youth in our study. While age-appropriate outreach and treatment services are available for youth in both the DTS and the DTES (47), the utility of these services to newly-recruited street-involved youth may be limited, given that research suggests that such populations have minimal uptake of treatment services (48). Further, both the DTS and the DTES suffer from a dearth of youth-targeted structural interventions such as assisted housing and harm reduction shelters (22). For example, qualitative research from our study setting has demonstrated that street-involved youth residing in downtown Vancouver reported that inflexible shelter rules and the stigma and lack of safety associated with single-room occupancy hotels outweighed the benefits of sleeping indoors. In turn, this lack of appropriate housing greatly increases the risk of further entrenchment within a street-based illicit drug scene (22). Given that public health experts have suggested prioritizing the prevention of injection drug use among vulnerable populations (19), the implementation of interventions to address the built environment, particularly among newly-recruited street-involved youth in the DTS, is needed.

Our study has a number of important limitations. First, we are unable to infer causal associations between reported neighborhood of residence and the risk behaviors that we analyzed as a result of the cross sectional nature of our analyses. Specifically, we were unable to elucidate the mechanisms by which neighborhood of residence modifies risk, though it is noteworthy that previous qualitative investigations of such mechanisms are consistent with our current findings (23, 24). Further, we are unable to determine the causal direction between reported residence in each neighbourhood of interest and the drug use patterns reported by study participants. It is noteworthy, however, that previous research conducted in our study setting suggests that drug use behaviours may be the result of immersion within social networks and illicit drug scenes unique to each neighbourhood of interest (23). Second, ARYS is not a random sample and its generalizability to other samples of street youth may therefore be limited. Third, because we relied primarily on self-report, risk behaviors among study participants may have been underreported as a result of social stigma (49). Fourth, while we based our analyses on previous research conducted among street-involved youth in our study setting and were therefore able to confirm that our current findings were consistent with previous analyses, it is possible that we were still unable to adjust for all variables that may have contributed to the differences that we observed between participants residing in the neighborhoods of interest. In this regard, it is important to note that the low power in our sample excluded the possibility of controlling for factors in our subanalysis of crystal methamphetamine initiation, and these results in particular should therefore be interpreted with caution. Finally, while youth participating in the study reported on neighbourhood of residence, it is possible given the transient nature of this population that some youth may have migrated between areas. This may have resulted in an underestimate of the risk factors reported by each neighbourhood subsample.

Our findings suggest that while the DTES remains the epicenter of drug market activity among our sample, the adjacent DTS neighborhood may play a key role in the transition among street youth from lower-risk street involvement to high-risk street entrenchment, and may also be an important site of initiation into crystal methamphetamine. As well, on a number of indicators of drug-related behaviors, no differences existed between street youth residing in the DTES and those residing in the more affluent DTS. These results suggest that future research is needed to investigate whether neighborhoods peripheral to illicit drug markets are sites of increased risk for drug use initiation and entrenchment within adult drug injecting scenes.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ochoa KC, Davidson PJ, Evans JL, Hahn JA, Page-Shafer K, Moss AR. Heroin overdose among young injection drug users in San Francisco. Drug Alc Depend. 2005 Dec 12;80(3):297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Small W, Rhodes T, Wood E, Kerr T. Public injection settings in Vancouver: Physical environment, social context and risk. Int J Drug Policy. 2007 Jan;18(1):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rhodes T, Judd A, Mikhailova L, et al. Injecting equipment sharing among injecting drug users in Togliatti City, Russian Federation: Maximizing the protective effects of syringe distribution. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35(3):293. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200403010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maher L, Dixon D. Policing and public health: Law enforcement and harm minimization in a street-level drug market. Brit J Criminol. 1999;39(4):488. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buxton J, Mehrabadi A, Preston E, Tu A. Vancouver site report for the Canadian Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use Report. Vancouver: City of Vancouver; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poret S, Tejedo C. Law enforcement and concentration in illicit drug markets. Eur J Pol Econ. 2006;22(1):99. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Small W, Wood E, Jurgens R, Kerr T. Injection drug use, HIV/AIDS and incarceration: Evidence from the Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study. HIV/AIDS Policy Law Rev. 2005 Dec;10(3):1, 5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtis R, Friedman SR, Neaigus A, Jose B, Goldstein M, Ildefonso G. Street-level drug markets: Network structure and HIV risk. Social Networks. 1995;17:229. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson DR, Flynn NM, Perales D. Effectiveness of syringe exchange programs in reducing HIV risk behavior and HIV seroconversion among injecting drug users. AIDS. 2001;15(11):1329. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200107270-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caulkins JP. Local drug markets response to focused police enforcement. Operations Research. 1993;41(5):848. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shannon K, Kerr T, Allinott S, Chettiar J, Shoveller J, Tyndall MW. Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(4):911–21. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhodes T. The ‘risk environment’: A framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. Int J Drug Pol. 2002;13(2):85. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanser F, Barnighausen T, Cooke GS, Newell M-L. Localized spatial clustering of HIV infections in a widely disseminated rural South African epidemic. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:8. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maas B, Fairbairn N, Kerr T, Li K, Montaner JSG, Wood E. Neighborhood and HIV infection among IDU: Place of residence independently predicts HIV infection among a cohort of injection drug users. Health and Place. 2007;13(2):432–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bluthenthal RN, Phuong Do D, Finch B, Martinez A, Edlin BR, Kral AH. Community characteristics associated with HIV risk among injection drug users in the San Francisco Bay area: A multilevel analysis. J Urban Health. 2007;84(5):14. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9213-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Généreux M, Bruneau J, Daniel M. Association between neighbourhood socioeconomic characteristics and high-risk injection behaviour amongst injection drug users living in inner and other city areas in Montréal, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kruse GR, Barbour R, Heimer R, et al. Drug choice, spatial distribution, HIV risk, and HIV prevalence among injection drug users in St. Petersburg, Russia. Harm Reduct J. 2009;31(6):22. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adlaf EM, Zdanowicz YM. A cluster-analytic study of substance problems and mental health among street youths. Am J Drug Alc Abuse. 1999;25(4):639–60. doi: 10.1081/ada-100101884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vlahov D, Fuller CM, Ompad DC, Galea S, Des Jarlais DC. Updating the Infection Risk Reduction Hierarchy: Preventing transition into injection. J Urban Health. 2004;81(1):14. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuller CM, Vlahov D, Arria AM, Ompad DC, Garfein R, Strathdee SA. Factors associated with adolescent initiation of injection drug use. Public Health Rep. 2001;116 (Suppl 1):136. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman SR, Kang SY, Deren S, et al. Drug-scene roles and HIV risk among Puerto Rican injection drug users in East Harlem, New York and Bayamon, Puerto Rico. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2002 Oct–Dec;34(4):363. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2002.10399977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krüsi A, Fast D, Small W, Wood E, Kerr T. Social and structural barriers to housing among street-involved youth who use illicit drugs. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2010;18(3):7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00901.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fast D, Small W, Wood E, Kerr T. Coming ‘down here’: Young people’s reflections on becoming entrenched in a local drug scene. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(8) doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fast D, Shoveller J, Shannon K, Kerr T. Safety and danger in downtown Vancouver: Understandings of place among young people entrenched in an urban drug scene. Health & Place. 2010;16(1):51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.City of Vancouver. Downtown South. Vancouver: City of Vancouver; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bungay V, Malchy L, Buxton JA, Johnson J, MacPherson D, Rosenfeld T. Life with jib: A snapshot of street youth’s use of crystal methamphetamine. Addiction Research & Theory. 2006;14(3):235–51. [Google Scholar]

- 27.UHRI. Drug Situation in Vancouver. Vancouver: Urban Health Research Initiative, BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wood E, Kerr T, Spittal PM, Tyndall MW, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT. The healthcare and fiscal costs of the illicit drug use epidemic: The impact of conventional drug control strategies and the impact of a comprehensive approach. BCMJ. 2003;45(3):130. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansen D. Street kids using crystal meth at ‘alarming’ rate. Vancouver Sun. 2008 April 2; [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuller CM, Borrell LN, Latkin CA, et al. Effects of race, neighborhood, and social network on age at initiation of injection drug use. Am J Pub Health. 2005;95:689–95. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.02178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kral AH, Lorvick J, Edlin BR. Sex and drug-related risk among populations of younger and older injection drug users in adjacent neighbourhoods in San Francisco. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;24(2):162. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200006010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hembree C, Galea S, Ahern J, et al. The urban built environment and overdose mortality in New York City neighborhoods. Health & Place. 2005;11(2):147–56. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernstein KT, Galea S, Ahern J, Tracy M, Vlahov D. The built environment and alcohol consumption in urban neighborhoods. Drug Alc Depend. 2007;91(2–3):244–52. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans GW. The built environment and mental health. J Urban Health. 2003;80(4):536–55. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galea S, Ahern J, Rudenstine S, Wallace Z, Vlahov D. Urban built environment and depression: A multilevel analysis. J Epi & Comm Health. 2005;59(10):822. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.033084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Essack Z, Slack C, Koen J, Gray G. HIV prevention responsibilities in HIV vaccine trials: complexities facing South African researchers. South African Medical Journal. 2010;100:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhodes T, Watts L, Davies S, et al. Risk, shame and the public injector: A qualitative study of drug injecting in South Wales. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(3):572–85. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wood E, Stolz J-A, Montaner JiSG, Kerr T. Evaluating methamphetamine use and risks of injection initiation among street youth: The ARYS study. Harm Reduction Journal. 2006;3(18):1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fairbairn N, Kerr T, Buxton JA, Li K, Montaner JS, Wood E. Increasing use and associated harms of crystal methamphetamine injection in a Canadian setting. Drug Alc Depend. 2007;88(2/3):313. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Werb D, Kerr T, Li K, Montaner J, Wood E. Risks surrounding drug trade involvement among street-involved youth. Am J Drug Alc Abuse. 2008;34(6):810–20. doi: 10.1080/00952990802491589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell L, Boyd N, Culbert L. A thousand dreams: Vancouver’s downtown eastside and the fight for its future. Vancouver: Greystone/D&M Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rachlis BS, Wood E, Li K, Hogg RS, Kerr T. Drug and HIV-related risk behaviors after geographic migration among a cohort of injection drug users. AIDS and Behavior. 2009:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9397-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deren S, Kang SY, Colon HM, et al. Migration and HIV risk behaviors: Puerto Rican drug injectors in New York City and Puerto Rico. Am J Pub Health. 2003;93:812–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lurie MN, Williams BG, Zuma K, et al. The impact of migration on HIV-1 transmission in South Africa: A study of migrant and nonmigrant men and their partners. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2003;30(2):149. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200302000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramjee G, Gouws E. Prevalence of HIV among truck drivers visiting sex workers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29(1):44. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riedner G, Hoffmann O, Rusizoka M, et al. Decline in sexually transmitted infection prevalence and HIV incidence in female barworkers attending prevention and care services in Mbeya Region, Tanzania. AIDS. 2006;20(4):609. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000210616.90954.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.The McCreary Centre Society. Between the cracks: Homeless youth in Vancouver. Vancouver: The McCreary Centre Society; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 48.The McCreary Centre Society. Against the odds: A profile of marginalized and street-involved youth in BC. Vancouver: The McCreary Centre Society; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Macalino GE, Celentano DD, Latkin C, Strathdee SA, Vlahov D. Risk behaviors by audio computer-assisted self-interviews among HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative injection drug users. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14(5):367. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.6.367.24075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]