Abstract

Objectives

To determine the association between complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use and antihypertensive medication adherence in older black and white adults.

Design

Cross-sectional

Setting

Patients enrolled in a managed care organization

Participants

2180 black and white adults, 65 years of age and older and prescribed antihypertensive medication.

Measurements

CAM use (i.e., health food and herbal supplements, relaxation techniques) for blood pressure control as well as antihypertensive medication adherence were collected via telephone survey between August 2006 and September 2007. Low medication adherence was defined as scores < 6 using the 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale.

Results

The mean age of participants was 75.0 + 5.6 years, 30.7% were black, 26.5% used CAM, and 14.1% had low antihypertensive medication adherence. In managing blood pressure, 30.5% of black and 24.7% of white participants used CAM in the last year and 18.4% of black and 12.3% of white participants reported low adherence to antihypertensive medication (P=0.005 and <0.001, respectively). After multivariable adjustment for socio-demographics, depressive symptoms and reduction in antihypertensive medications due to cost, the prevalence ratios of low antihypertensive medication adherence associated with CAM use were 1.56 (95% CI: 1.14–2.15; P=0.006) and 0.95 (95% CI 0.70, 1.29; P=0.728) among blacks and whites, respectively (P value for interaction=0.069).

Conclusion

In this cohort of older managed care patients, CAM use was associated with low adherence to antihypertensive medication among blacks but not whites.

Keywords: complementary and alternative medicine, hypertension, medication adherence, older adults

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension is a global health problem affecting 65 million persons in the United States (US) and about 1 billion persons worldwide1. Despite the availability of effective pharmacologic therapies, low adherence to antihypertensive medication remains a public health challenge 2–4 and is associated with increased health care costs and with high rates of cardiovascular disease and hospitalization5;6. It is estimated that adherence rates are approximately 50% for chronic medications4. In a meta-analysis, the odds ratio of blood pressure control among patients adherent to antihypertensive medications compared to those not adherent was 3.44 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.60, 7.37)7. Identifying modifiable factors that affect antihypertensive medication adherence in the older adults could help target interventions to reduce low medication adherence, improve blood pressure control and decrease cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Multiple factors influencing patient adherence to prescribed pharmacologic therapies have been described and include demographic, treatment, clinical, and behavioral variables3;8;9. However, there is a lack of understanding of how various factors influence adherence in older adults and which patient groups are at greatest risk of low medication adherence. One such factor is the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). CAM has been defined by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine as a group of diverse medical and health care systems, products, and practices that are not presently considered part of conventional medical care10. It is generally assumed that complementary medicine is used in conjunction with conventional medicine whereas alternative medicine is used in place of conventional medicine; however, many patients replace conventional medical care with complementary therapies. CAM use has been reported to be common among patients with hypertension11–16. However, the relationship between CAM use and adherence to antihypertensive medications has not been well documented in older black and white adults.

Previous studies have reported lower adherence to medications among blacks compared to whites8;17;18. In addition, prior research has identified different rates of CAM use among black and white adults19–21. Therefore, CAM therapies for blood pressure control may affect conventional medical care for hypertension differently for blacks and whites. The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship of CAM use to antihypertensive medication adherence in black and white older adults.

METHODS

Study population and timeline

These data are derived from the baseline interview of the Cohort Study of Medication Adherence among Older Adults [CoSMO]. Participants in CoSMO include older adults with essential hypertension who were enrolled in Humana, a large managed care organization (MCO), and prescribed antihypertensive medication. The primary goal of CoSMO is to investigate the multiple factors that influence antihypertensive medication adherence; the study design and baseline characteristics have been previously described 8. In brief, adults 65 years and older with essential hypertension were randomly selected from the roster of a large MCO in southeastern Louisiana and contacted to participate in a prospective cohort study. The catchment area for CoSMO reflects a demographically diverse group of individuals in urban and suburban areas. Recruitment was conducted from August 21, 2006 to September 30, 2007 and 2194 participants were enrolled. Compared to participants, those who refused to participate (n=2217) were more likely to be male (50.4% versus 41.5%, p<0.001), white (84.5% versus 68.8%, p<0.001), and older (76.3 years versus 74.5 years, p<0.001). For the current analysis, 14 participants who report their race to be other than white or black were excluded. All participants provided verbal informed consent, and CoSMO was approved by the Ochsner Clinic Foundation’s Institutional Review Board and the privacy board of the MCO8.

Study measures

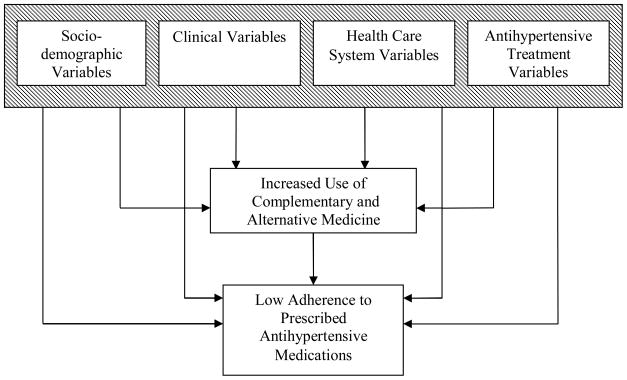

The baseline survey was administered by telephone using trained interviewers and lasted 30–45 minutes. Of relevance to the current analyses, the survey included assessment of sociodemographic factors, clinical factors, health care system factors, antihypertensive medication treatment-related variables, CAM use for blood pressure management and adherence to antihypertensive medication (Figure 1)3. Data on co-morbid conditions and antihypertensive medication persistency were obtained from the administrative and pharmacy databases, respectively, of the MCO. These domains are described in detail below.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework of Variables, Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use, and Low Antihypertensive Medication Adherence (modified from Curr Opin Cardiol 20043)

Socio-demographic and clinical variables

Sociodemographic characteristics and duration of hypertension were obtained through self-report. Comorbid conditions were extracted from the administrative database of the MCO and used to generate the Charlson comorbidity index 22;23. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using self-reported height and weight. Depressive symptoms were determined with the 20-item National Institute of Mental Health Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). CES-D scores can range from 0 to 60 with a score ≥ 16 used to define the presence of depressive symptoms in the current study24.

Health care system and antihypertensive treatment variables

Participant satisfaction with health care was assessed using three components of the previously validated Group Health Association of America (GHAA) Consumer Satisfaction Survey: overall satisfaction, access to care and communication25;26. For each question in the component scales, there was a 5 point Likert-scale response optionranging from poor to excellent. Responses of poor and fair were classified as not satisfied and responses of good, very good and excellent were classified as satisfied. A question, “In the last year, have you ended up taking less high blood pressure medication than was prescribed because of the cost” was used to assess whether participants reduced their antihypertensive medication because of cost. The number of classes of antihypertensive medication being taken was obtained from the pharmacy database of the MCO.

CAM

Use of CAM was assessed with questions derived from a previously validated survey 27. The CAM modalities selected for the survey instrument (see Appendix) focused on the use of CAM most frequently cited as effective means of reducing blood pressure: health food (including fish oil, fiber, L-arginine, co-enzyme Q10) and herbal (including garlic, snakeroot, yarrow, Chinese herbs) supplements, and relaxation techniques (including yoga, meditation, or other relaxation techniques). CAM use was defined as the use of these modalities at least several times or on a regular basis in the year prior to the baseline survey.

Medication Adherence

Self-reported adherence to antihypertensive medications was ascertained using the eight-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8). This measure was designed to facilitate the recognition of barriers to and behaviors associated with adherence to chronic medications such as antihypertensive drugs. Previously published in its entirety9, this scale provides information on behaviors related to medication use that may be unintentional (e.g., forgetfulness) or intentional (e.g., not taking medications due to side effects). A sample question is “Do you sometimes forget to take your high blood pressure medication?” The MMAS-8 has been determined to be reliable (α= 0.83) and significantly associated with blood pressure control (p<0.05) in individuals with hypertension (i.e., low adherence levels were associated with lower rates of blood pressure control) 9. Also, the MMAS-8 has been shown to have high concordance with antihypertensive medication pharmacy fill rates 28. Scores on the MMAS-8 can range from zero to eight with scores of <6, 6 to <8, and 8 reflecting low, medium and high adherence, respectively 9;28. In order to focus on identifying participants with low medication adherence, we grouped the MMAS-8 into 2 categories: low (MMAS-8 <6) and not low adherence (MMAS-8 ≥ 6) for the current analyses.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were stratified by race because of previously published differences in CAM use and medication adherence in blacks and whites. The interaction of CAM use and race on low antihypertensive medication adherence was marginally significant (p = 0. 069). Rates of CAM use and low medication adherence were calculated by race and by participant characteristics. Chi-square tests were used to determine the statistical significance of differences. Prevalence ratios of low antihypertensive medication adherence associated with CAM use were calculated using separate log binomial regression models for blacks and whites adjusted for age, gender, education, marital status, depressive symptoms, and the reduction of antihypertensive medication due to cost. Given that there are multiple comparisons, we provide exact P-values. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Participant characteristics, CAM use, and medication adherence

The mean age of study participants (n=2180) was 75.0 + 5.6 years, 30.7% were black, 58.8% were women, 14.1% had low antihypertensive medication adherence8, and 26.5% used CAM in managing their blood pressure. Compared to whites, blacks were significantly younger, less likely to be a high school graduate, and married, and were more likely to have a hypertension diagnosis longer than 10 years, more comorbid conditions, and a higher BMI8.

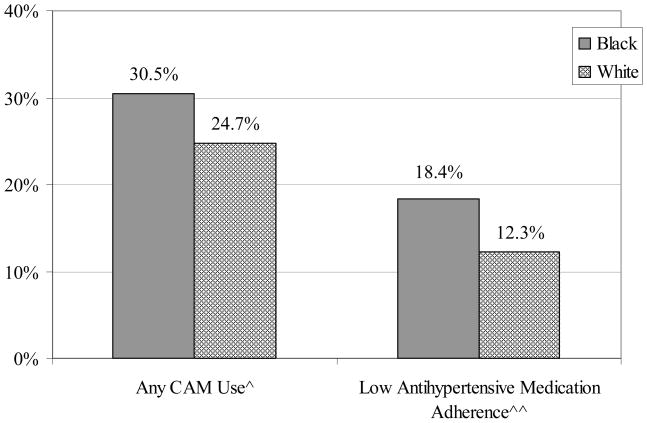

A significantly higher percentage of blacks compared to whites were CAM users and had low antihypertensive medication adherence (Figure 2). In assessing types of CAM use by race, blacks were more likely to use herbal supplements compared to whites (15.7% versus 5.4% respectively; P< 0.001); there were no differences across racial groups in use of health food supplements (14.2% for blacks versus 16.3% for whites; P=0.210) or relaxation techniques (8.1% for blacks versus 7.6% for whites; P=0.680). The majority of participants who used CAM for blood pressure management on a regular basis had discussed this use with their health care provider and the results were similar across race with the exception of health food supplements: 76.1% of blacks and 87.5% of whites using health food supplements regularly had told their health care provider (P=0.012); 69.6% of blacks and 70.9% of whites using herbal supplements had told their health care provider (P=0.592); and 65.6% of blacks and 50.7% of whites using relaxation techniques had discussed the use with their health care provider (P=0.177).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use and Low Antihypertensive Medication Adherence by Race. CAM use-complementary/alternative medicine use to help control blood pressure includes any of the following: health food supplements include fish oil, fiber, L-arginine, co-enzyme Q10; herbal supplements include garlic, snakeroot, yarrow, or Chinese herbs; and relaxation techniques include yoga, meditation, or other relaxation techniques. ^p=0.005 ^^p<0.001

Variables associated with CAM use and low antihypertensive medication adherence by race

Among blacks, participants with a high school education or more and those reducing antihypertensive medications due to cost were more likely to be CAM users. Among whites, participants who were younger than 75 years, had a comorbidity index ≥ 2, and were filling 3 or more classes of antihypertensive medication were more likely to be CAM users (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics by Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use

| Any CAM Use | ||

|---|---|---|

| Blacks (N=670) | Whites (N=1510) | |

| Socio-demographic Variables | ||

| Male, % | 30.8 | 24.2 |

| Female, % | 30.3 | 25.1 |

| Under 75 years old, % | 31.9 | 27.6 |

| 75 years or older, % | 28.5 | 22.0* |

| High School graduate or more, % | 34.9 | 24.4 |

| Did not complete High School, % | 23.0** | 26.6 |

| Married, % | 29.7 | 24.7 |

| Not married, % | 31.1 | 24.7 |

| Clinical Variables | ||

| Hypertension duration ≥ 10 years, % | 30.5 | 25.0 |

| Hypertension duration < 10 years, % | 30.5 | 24.4 |

| Co-morbid index score ≥ 2, % | 29.4 | 27.3 |

| Co-morbid index score < 2, % | 31.8 | 22.4* |

| Body mass index: ≥ 25 kg/m2, % | 31.5 | 24.5 |

| Body mass index: < 25 kg/m2, % | 25.0 | 25.4 |

| Depressive symptoms present, % | 35.0 | 27.1 |

| Depressive symptoms absent, % | 29.6 | 24.4 |

| Health Care System Variables | ||

| Satisfied with overall healthcare, % | 30.5 | 24.4 |

| Not satisfied with overall healthcare, % | 31.0 | 31.7 |

| Satisfied with communication, % | 30.0 | 24.6 |

| Not satisfied with communication, % | 35.0 | 25.8 |

| Satisfied with access to healthcare, % | 30.5 | 24.7 |

| Not satisfied with access to healthcare, % | 29.7 | 25.0 |

| Reduced antihypertensive medication due to cost, % | 55.8 | 35.3 |

| Did not reduce antihypertensive medication due to cost, % | 28.7† | 24.5 |

| Antihypertensive Treatment Variables | ||

| 3+ classes of antihypertensive medication, % | 32.4 | 27.6 |

| 1 or 2 classes of antihypertensive medication, % | 28.0 | 22.2* |

Excludes persons with race other than white or black (n=14); Includes 2180 older adults in a managed care setting; survey collected from August 2006-September 2007

CAM use-complementary/alternative medicine use to help control blood pressure includes any of the following: health food supplements include fish oil, fiber, L-arginine, co-enzyme Q10; herbal supplements include garlic, snakeroot, yarrow, or Chinese herbs; and relaxation techniques include yoga, meditation, or other relaxation techniques.

p < 0.05;

p <0.01;

p <0.001 for comparisons within race groups

Black participants with depressive symptoms and those reducing antihypertensive medication due to cost were more likely to have low antihypertensive medication adherence (Table 2). Among whites, participants younger than 75 years, with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, depressive symptoms, and who were reducing antihypertensive medications due to cost were more likely to have low antihypertensive medication adherence.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics by Low Antihypertensive Medication Adherence

| Low Antihypertensive Medication Adherence | ||

|---|---|---|

| Blacks (N=670) | Whites (N=1510) | |

| Socio-demographic Variables | ||

| Male, % | 16.4 | 12.1 |

| Female, % | 19.2 | 12.4 |

| Under 75 years old, % | 19.6 | 14.7 |

| 75 years or older, % | 16.7 | 10.0** |

| High School graduate or more, % | 19.7 | 12.1 |

| Did not complete High School, % | 16.1 | 13.3 |

| Married, % | 19.7 | 12.0 |

| Not married, % | 17.2 | 12.7 |

| Clinical Variables | ||

| Hypertension duration ≥ 10 years, % | 17.8 | 11.4 |

| Hypertension duration < 10 years, % | 19.6 | 13.6 |

| Co-morbid index score ≥ 2, % | 20.1 | 12.1 |

| Co-morbid index score < 2, % | 16.5 | 12.4 |

| Body mass index: ≥ 25 kg/m2, % | 19.2 | 13.6 |

| Body mass index: < 25 kg/m2, % | 13.0 | 8.8* |

| Depressive symptoms present, % | 34.0 | 17.7 |

| Depressive symptoms absent, % | 15.5† | 11.5* |

| Health Care System Variables | ||

| Satisfied with overall healthcare, % | 17.7 | 12.1 |

| Not satisfied with overall healthcare, % | 28.6 | 16.7 |

| Satisfied with communication, % | 17.6 | 11.9 |

| Not satisfied with communication, % | 25.0 | 15.9 |

| Satisfied with access to healthcare, % | 18.0 | 12.1 |

| Not satisfied with access to healthcare, % | 24.3 | 15.0 |

| Reduced antihypertensive medication due to cost, % | 39.5 | 44.1 |

| Did not reduce antihypertensive medication due to cost, % | 16.9† | 11.5† |

| Antihypertensive Treatment Variables | ||

| 3+ classes of antihypertensive medication, % | 19.0 | 12.6 |

| 1 or 2 classes of antihypertensive medication, % | 17.5 | 11.9 |

Excludes persons with race other than white or black (n=14); Includes 2180 older adults in a managed care setting; survey collected from August 2006-September 2007

p < 0.05;

p <0.01;

p <0.001 for comparisons within race groups

CAM use and low antihypertensive medication adherence

Among blacks, low antihypertensive medication adherence was more common among those using CAM (Table 3). There was no difference in low antihypertensive medication adherence among whites using versus not using CAM. After multivariable adjustment for socio-demographics, depressive symptoms and reduction of medications due to cost, the prevalence ratio of low antihypertensive medication adherence associated with CAM use was 1.56 (95% CI: 1.14–2.15) and 0.95 (95% CI 0.70, 1.29) among blacks and whites, respectively (P value for interaction=0.069).

Table 3.

Prevalence and Prevalence Ratios of Low Antihypertensive Medication Adherence associated with CAM Use for Blacks and Whites.

| Prevalence, % | P-Value | Sociodemographic- adjusted^ Prevalence Ratio (95% CI) | P- Value | Multivariable- adjusted^^ Prevalence Ratio (95% CI) | P- Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Blacks | ||||||

| No CAM Use | 26.0% | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |||

| CAM Use | 15.0% | <0.001 | 1.71 (1.24, 2.36) | 0.001 | 1.56 (1.14, 2.15) | 0.006 |

|

Whites | ||||||

| No CAM Use | 12.3% | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |||

| CAM Use | 12.2% | 0.956 | 0.97 (0.71, 1.33) | 0.872 | 0.95 (0.70, 1.29) | 0.728 |

Excludes persons with race other than white or black (n=14); Includes 2180 older adults in a managed care setting; survey collected from August 2006-September 2007

CAM use-complementary/alternative medicine use to help control blood pressure includes any of the following: health food supplements include fish oil, fiber, L-arginine, co-enzyme Q10; herbal supplements include garlic, snakeroot, yarrow, or Chinese herbs; and relaxation techniques include yoga, meditation, or other relaxation techniques.

CI-confidence interval

Adjusted for age, gender, marital status, and education

Adjusted for age, gender, marital status, education, depressive symptoms, and reduction of antihypertensive medication due to cost

DISCUSSION

A substantial portion of older adults with hypertension in the CoSMO study used CAM in addition to prescribed medications to help control their blood pressure. It has been speculated that CAM use may negatively affect adherence to prescribed therapies 3. In the current study, black participants reporting CAM use were more likely to have low adherence to antihypertensive medications; thus, CAM use may be an important modifiable barrier or a signal of other barriers (e.g. side effects and costs of medications) to antihypertensive medication adherence and subsequent blood pressure control in older black patients.

The use of CAM is occurring despite the fact that the manufacturing of these remedies is not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and the risks and benefits of these therapies are not well-defined 29. Rates of CAM use among older adults in previous studies have varied widely 11;12;30–33. Rates of CAM use in prior studies are higher than the use reported in our study; however, we inquired about the use of CAM specifically for hypertension management. Use of CAM to control blood pressure was higher in our study (i.e., 26.5%) than previously reported by Bell where only 7.8% of older adults used CAM to treat their hypertension 12.

In our study, blacks compared to whites were significantly more likely to use CAM in general and herbal supplements in particular to help control their blood pressure. High use of CAM among blacks has been previously reported 19;21. Prior research has revealed also that many patients did not disclose the use of CAM to their health care provider 11;34 and blacks compared to whites, Hispanics and Asians were less likely to inform their physician or pharmacist about CAM use35. In the current study, a higher percentage of participants disclosed their CAM use to their health care providers than previously reported and may be attributable to differences in wording of questions, sample selection, or secular trends. Despite the high rates of disclosure of CAM use in this study, blacks were less likely than whites to discuss use of health food supplements for blood pressure control with their health care providers. It is possible that in the CoSMO population, use of herbal supplements including home remedies may be a prominent part of the black culture 19;21 and may not be viewed as relevant in traditional health care settings. In a study of CAM use in older community dwelling adults, the primary reasons for not disclosing CAM use were “not being asked” (38.5%), “didn’t think about it” (22.0%), and “didn’t think it was important to my care” (22.0%) 31. Not informing one’s health care provider and substituting CAM for conventional medical care may be especially problematic in older adults who are at risk for health complications related to concomitant use of conventional and CAM or to low medication adherence resulting in poor blood pressure control. Although there is evidence that some supplements (e.g. fish oils) may reduce blood pressure, they may not work as well as prescribed medications 13;36–38.

Regarding variables associated with CAM use, there were differences between black and white participants. For blacks, higher educational status and reducing antihypertensive medications because of the cost were associated with CAM use. The associations between higher education and CAM use and costs of conventional care and CAM use have been previously reported11;20. White participants younger than 75 years of age were more likely to use CAM therapies for blood pressure control. Although differences in CAM use by age among older adults have been inconsistently reported in the literature 11;31, higher use of CAM by the younger age group may be a cohort, rather than an age, effect 11. That is, recent generations have had increased exposure to CAM through media and social networks and therefore may be more familiar and comfortable with using these therapies. Related to previous findings revealing that worsening self-perceived health status was associated with CAM use in whites20;21;39, white participants in CoSMO with more comorbid conditions and increased number of antihypertensive medications were more likely to use CAM therapies for blood pressure control.

With respect to the association between variables and low antihypertensive medication adherence, there were common factors among blacks and whites: depressive symptoms and reducing antihypertensive medications because of costs were associated with low antihypertensive medication adherence in both groups. Depression is common in patients with chronic diseases including hypertension and is associated with poor health outcomes40–43. Prior reports have demonstrated that depressive symptoms are associated with worse blood pressure control and with the onset of complications of hypertension 44. More recently, investigators have reported cross-sectional associations of depressive symptoms with low antihypertensive medication adherence 45–47. The relationship between cost of medications and low antihypertensive medication adherence has been well described even in insured populations48;49. Additionally, younger white participants were more likely to be low adherers- a finding that has been previously reported18;50. White participants with BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 had a higher prevalence of low medication adherence. Given that high BMI is often reflective of low adherence to lifestyle modifications, it is possible that patients who are not adherent to lifestyle modifications may not be adherent to other recommendations for blood pressure management.

Prior published reports indicated adherence to antihypertensive medications is related to faith in the physician51. Other researchers have found that patient-physician trust may moderate low adherence to medication due to cost pressures52. These findings suggest that satisfaction with the doctor-patient relationship may be an important determinant of medication adherence. Although we did not capture faith and trust in the health care provider as part of the baseline survey, we did measure 3 components of satisfaction including communication with the health care provider. While there was a trend for white and black participants who were not satisfied with the communication with the health care provider to have a higher prevalence of low antihypertensive medication adherence, the difference was not statistically significant in either group. No relationship between satisfaction and CAM use was identified in this study. Further research examining the effect of the provider-patient relationship on medication adherence is warranted.

Consistent with our conceptual model, blacks using CAM for blood pressure control were significantly more likely to have low antihypertensive medication adherence; however, low adherence was not associated with CAM use among whites These findings suggest that blacks may be substituting CAM therapies for conventional medical care whereas whites may be complementing conventional care with CAM therapies. As mentioned earlier, this dissimilarity may reflect cultural differences in CAM use between whites and blacks. Although others have investigated the relationship between CAM use and antihypertensive medication adherence in a small convenience sample of patients attending an outpatient clinic in the United Kingdom16, differential effects by race have not been fully explored.

Study limitations and strengths

The results presented are observational. Additionally, recruitment of participants was restricted to one region of the US and older adults. While the current manuscript provides important new data on the relationship between CAM use for blood pressure management and adherence to antihypertensive medications among blacks and whites, future work is needed to determine the effects of types of CAM on medication adherence for other chronic conditions. In addition, the data are self-reported and, thus, there is a potential for misclassification. Information on whether participants’ health care providers had prescribed CAM for blood pressure management was not available. Finally, the current study is limited to English-speaking older adults with health insurance. Despite these limitations, the study includes many strengths including its large sample size and broad data collection. The study population is diverse with respect to socio-demographics and the presence of cardiovascular risk factors allowing analysis of the relationship between use of CAM and low antihypertensive medication adherence across race subgroups to distinguish which groups of older adults are at greatest risk of low adherence. The restriction of our sample to older adults in a managed care setting minimizes the confounding effects of health insurance, access to medical care, and employment status in the older adult population. Because hypertension is a prevalent disease among older adults, the results of this study may be useful in the evaluation and management of a substantial segment of the population.

CONCLUSION

Our findings indicate that a substantial proportion of black and white older adults enrolled in a MCO are combining CAM use with conventional medical care in the management of their hypertension. As suggested by the current study, CAM use may have a negative effect on antihypertensive medication adherence in older black adults. Further work is required to understand the attitudinal, cultural and generational beliefs that lead to the use of CAM in hypertension management 32, and the role of CAM use on medication adherence and blood pressure control. Studies of CAM use in clinical practice and how patients use CAM to manage their chronic diseases will improve both communication between patients and their health care providers and clinical care 14;53. Health care providers should ask their patients about CAM use, and among those using CAM, discuss the importance of adherence to their prescribed medication.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Grant Number R01 AG022536 from the National Institute on Aging (Krousel-Wood-principal investigator). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health. The NIH was not involved in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, or preparation of the manuscript.

Use of MMAS-8: Permission for use of MMAS-8 is required. Licensure agreement is available from: Donald E. Morisky, ScD, ScM, MSPH, Professor, Department of Community Health Sciences, UCLA School of Public Health, 650 Charles E. Young Drive South, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1772.

Appendix Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey (adapted from Lengacher et al Oncology Nursing Forum 200327)

| 1. In the last year, have you used health food supplements (such as fish oil, fiber, L- arginine, or co-enzyme Q-10) to help control your blood pressure? | |||

| Response options: | Yes | No | |

| If the answer is “Yes,” ask Question 1a. If “No,” go to Question 2. | |||

| a. How often have you used health food supplements? | |||

| Response options: | One time | Several times | On a regular basis |

| If the response to the above question “On a regular basis,” ask: | |||

| b. Have you discussed this use with your health care provider? | |||

| Response options: | Yes | No | |

| 2. In the last year, have you used herbal supplements (such as garlic, snakeroot, yarrow, or Chinese herbs) to help control your blood pressure? | |||

| Response options: | Yes | No | |

| If the answer is “Yes,” ask Question 2a. If “No,” go to Question 3. | |||

| a. How often have you used herbal supplements? | |||

| Response options: | One time | Several times | On a regular basis |

| If the response to the above question “On a regular basis,” ask: | |||

| b. Have you discussed this use with your health care provider? | |||

| Response options: | Yes | No | |

| 3. In the last year, have you used yoga, meditation, or relaxation techniques to help control your blood pressure? | |||

| Response options: | Yes | No | |

| If the answer is “Yes,” ask Question 3a. If “No,” then stop. | |||

| a. How often have you done yoga, meditation, or relaxation techniques? | |||

| Response option: | One time | Several times | On a regular basis |

| If the response to the above question “On a regular basis,” ask: | |||

| b. Have you discussed this practice with your health care provider? | |||

| Response options: | Yes | No | |

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. Drs. Morisky and Krousel-Wood have both participated in Expert Input Forums on Medication Adherence for Merck.

Author Contributions: All authors listed on the manuscript meet the criteria for authorship stated in the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to the Biomedical Journals. Design: Krousel-Wood; Methods: Krousel-Wood, Muntner, Morisky, He; Subject Recruitment and data collections: Krousel-Wood, Stanley; Analysis: Krousel-Wood, Muntner, Webber, Islam, Stanley, Joyce, Holt; and preparation of the manuscript: Krousel-Wood, Muntner, Islam, Joyce, Holt, Morisky, Webber, He

References

- 1.Ong KL, Cheung BM, Man YB, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among United States adults 1999–2004. Hypertension. 2007;49:69–75. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252676.46043.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burnier M, Santschi V, Favrat B, et al. Monitoring compliance in resistant hypertension: important step in patient management. J Hypertens. 2003;21:S37–S42. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200305002-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krousel-Wood M, Thomas S, Muntner P, et al. Medication adherence: A key factor in achieving blood pressure control and good clinical outcomes in hypertensive patients. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19:357–362. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000126978.03828.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haynes RB, McDonald HP, Garg AX. Helping patients follow prescribed treatment: Clinical applications. JAMA. 2002;288:2880–2883. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schiff GD, Fung S, Speroff T, et al. Decompensated heart failure: Symptoms, patterns of onset, and contributing factors. Am J Med. 2003;114:625–630. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, et al. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care. 2005;43:521–530. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163641.86870.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiMatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, et al. Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: Aa meta-analysis. Med Care. 2002;40:794–811. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krousel-Wood MA, Muntner P, Islam T, et al. Barriers to and Determinants of Medication Adherence in Hypertension Managements: Perspective of the Cohort Study of Medication Adherence among Older Adults (CoSMO) Med Clin N Am. 2009;93:753–769. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood MA, et al. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens. 2008;10:348–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 10.National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. What is CAM? 2009 http//nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/ 11-25-2008. Ref Type: Online Source.

- 11.Astin J, Pelletier K, Marie A, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among the elderly persons. One-year analysis of a Blue Shield Medicare supplement. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M4–M9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.1.m4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bell RA, Suerken CK, Grzywacz JG, et al. CAM use among older adults age 65 or older with hypertension in the United States: General use and disease treatment. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12:903–909. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States 1990–1997: Results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–1575. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kessler RC, Davis RB, Foster DR, et al. Long-term trends in the use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in teh United States. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:262–268. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-4-200108210-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gohar F, Greenfield SM, Beevers DG, et al. Self-care and adherence to medication: A survey in the hypertension outpatient clinic. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyre A, Krousel-Wood MA, Muntner P, et al. Prevalence and predictors of poor antihypertensive medication adherence in an urban health clinic setting. J Clin Hypertens. 2007;9:179–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.06372.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monane M, Bohn RL, Gurwitz JH, et al. The effects of initial drug choice and comorbidity on antihypertensive therapy compliance: Rresults from a population-based study in the elderly. Am J of Hypertens. 1997;10:697–704. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown CM, Barner JC, Richards KM, et al. Patterns of complementary and alternative medicine use in African Americans. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:751–758. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.6392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham RE, Ahn AC, Davis RB, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine therapies among racial and ethnic minority adults: Results from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey. J National Med Assoc. 2005;4:535–545. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ni H, Simile C, Hardy AM. Utilization of complementary and alternative medicine by United States adults: Results from the 1999 National Health Interview Survey. Med Care. 2002;40:353–358. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200204000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidiity in Longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM Administrative Databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measure. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krousel-Wood MA, Re R, Kleit A, et al. Patient and physician satisfaction in a clinical study of telemedicine in a hypertensive patient population. J Telemed Telecare. 2001;7:206–211. doi: 10.1258/1357633011936417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yacavone RF, Locke GR, Gostout CJ, et al. Factors influencing patient satisfaction with GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:703–710. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.115337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lengacher C, Bennett MP, Kipp KE, et al. Design and testing of the use of a complementary and alternative therapies survey in women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30:811–821. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.811-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krousel-Wood MA, Islam T, Webber LS, et al. New Medication adherence scale versus pharmacy fill rates in hypertensive seniors. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:59–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chagan L, Loselovich A, Asherova L, et al. Use of alternative pharmacotherapy in management of cardiovascular diseases. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8:270–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arcury TA, Suerken CK, Grzywacz JG, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among older adults: Ethnic variation. Ethnicity Dis. 2006;16:723–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheung CK, Wyman JF, Halcon LL. Use of complementary and alternative therapies in community-dwelling older adults. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:997–1006. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foster DF, Phillips RS, Hamel MB, et al. Alternative medicine use in older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1560–1565. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ness J, Cirillo D, Weir D, Nisly N, et al. Use of complementary medicine in older Americans: Results from the Health and Retirement Study. Gerontologist. 2005;45:516–524. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.4.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Van Rompay MI, et al. Perceptions about complementary therapies relative to conventional therapies among adults who use both: Results from a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:344–351. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-5-200109040-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuo GM, Hawlye ST, Weis IT, et al. Factors associated with herbal use among urban multiethnic primary care patients: A cross sectional survey. BMC Complemen Altern Med. 2004;4:18. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krousel-Wood MA, Muntner P, He J, et al. Primary prevention of essential hypertension. Med Clin N Am. 2004;88:223–238. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(03)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whelton PK, He J, Appel LJ, et al. Primary prevention of hypertension: clinical and public health advisory from the National High Blood Pressure Education Program. JAMA. 2002;288:1882–1888. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilburn AJ, King DS, Glisson J, et al. The natural treatment of hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 2004;6:242–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2004.03250.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Astin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine: Results of a national study. JAMA. 1998;279:1548–1553. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bogner HR, Cary MS, Bruce ML, et al. The role of medical comorbidity in outcome of major depression in primary care: The PROSPECT study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:861–868. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.10.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bogner HR, Morales KH, Post EP, et al. Diabetes, depression, and death: A randomized controlled trial of a depression treatment program for older adults based in primary care (PROSPECT) Diabetes Care. 2007;30:3005–3010. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3278–3285. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ziegelstein RC, Fauerbach JA, Stevens SS, et al. Patients with depression are less likely to follow recommendations to reduce cardiac risk during recovery from a myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1818–1823. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scalco AZ, Scalco MZ, Azul JB, et al. Hypertension and depression. Clinics. 2005;60:241–250. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322005000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: Meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim MT, Han HR, Hill MN, et al. Depression, substance use, adherence behaviors, and blood pressure in urban hypertensive black men. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:24–31. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang PS, Bohn RL, Knight E, et al. Noncompliance with antihypertensive medications: The impact of depressive symptoms and psychosocial factors. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:504–511. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.00406.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hsu J, Price M, Huang J, et al. Unintended consequences of caps on Medicare drug benefits. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2349–2359. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa054436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taira DA, Wong KS, Frech-Tamas F, et al. Copayment level and compliance with antihypertensive medication: Analysis and policy implications for managed care. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12:678–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marentette MA, Gerth WC, Billings DK, et al. Antihypertensive persistence and drug class. Can J Cardiol. 2002;18:649–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Svensson S, Kjellgren KI, Ahlner J, et al. Reasons for adherence with antihypertensive medication. Int J Cardiol. 2000;76:157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(00)00374-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Piette JD, Heisler M, Krein S, et al. The role of patient-physician trust in moderating medication nonadherence due to cost pressures. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1749–1755. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.15.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kleinman A, Eisenberg DM, Good B. Culture, illness, and care: Clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:251–258. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-2-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]