Abstract

Fatigue is a common, disabling symptom for individuals with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). This study 1) examined sex differences in the relations between daily changes in positive and negative interpersonal events and same-day and next-day fatigue; and 2) tested positive affect and negative affect as mediators of the associations between changes in interpersonal events and fatigue. Reports of fatigue, number of positive and negative interpersonal events, and positive and negative affect were assessed daily for 30 days via diaries in 228 men and women diagnosed with RA. Days of higher than average daily positive events were associated with both decreased same-day fatigue and increased next-day fatigue, but only among women. Sex differences in same-day relations between positive events and fatigue were mediated by increases in positive affect. For both sexes, days of higher than average daily negative events related to increased same-day and next-day fatigue, and the same-day relations between negative events and fatigue were mediated by increases in negative affect. A more nuanced understanding of similarities and differences between men and women in the associations between changes in interpersonal events and fatigue may inform future interventions for RA fatigue.

Keywords: Fatigue, pain, arthritis, daily events, social relations

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease characterized by joint pain, swelling, and stiffness that affects approximately 1% of adults, 75% of them women 34. Fatigue is a very common and disabling symptom in RA. Over 80% of patients report that they routinely experience significant fatigue, and persistent fatigue is one of the biggest obstacles to optimizing function in these individuals 21, 23. Indeed, when asked to prioritize their symptoms for targeted behavioral treatment, RA patients nominate fatigue more frequently than pain, negative affect, or social relations 6.

Because characteristics of the disease such as duration and pain severity are strongly related to reports of fatigue in RA patients, many investigators have conceptualized fatigue primarily as a reflection of the disease process. Yet a body of research indicates that negative and positive social factors also contribute to the experience of fatigue 27. In cross-sectional studies, negative life events and social support are associated with fatigue levels in RA patients over and above the contributions of disease activity and depression 9, 14, 29. Because the bulk of these studies have employed research designs with only one or two measurement occasions, scant data are available to examine potential mechanisms linking the social environment with fatigue. Diary reports of interpersonal experiences and fatigue that are collected repeatedly over time provide a valuable method of examining their covariation.

Multilevel modeling of diary data enables researchers to address both within-person questions (e.g., Are days with more negative interpersonal events associated with higher fatigue?) and between-person questions (e.g., Does the daily association between negative interpersonal events and fatigue differ for men and women?). In a recent diary study of women with chronic pain from RA, osteoarthritis (OA), or fibromyalgia (FM), a multilevel model revealed that days of increased negative interpersonal events were associated with increases, and days of increased positive interpersonal events with decreases, in same-day fatigue 19. Several key questions can be distilled from these intriguing findings. First, because the study included only women, it is important to determine whether the within-person relations between interpersonal events and fatigue are similar for men and women with chronic pain. There is reason to expect sex differences in event-fatigue associations. Compared to men, women have social networks that include more individuals they consider to be close 2, 10, and rate their experiences in interactions with others as more intense and intimate 7. Relative to men, women are more invested in their relationships and thus interpersonal events may exert a greater impact on the fatigue of women than men. Some evidence also suggests that women rely more than men on situational cues to determine their internal states 20, and therefore may be more likely than men to make use of interpersonal events to assess their own fatigue.

A second issue involves the mechanisms through which interpersonal events relate to fatigue. One potential path is through affect. Recent work has highlighted the link between positive events and positive affect 8, 36, and positive affect has a strong inverse association with fatigue 37. Along the same line, negative events are related to increased negative affect 36, which in turn is associated with elevated fatigue 24. The present study is the first to investigate whether positive and negative affect mediate the relations between interpersonal events and fatigue in chronic pain patients.

A third issue pertains to the carry-over effects of interpersonal events on fatigue from one day to the next day. Parrish, Zautra and Davis (2008) observed that days with higher than average positive interpersonal events were associated with increased next-day fatigue for women with RA or FM but not for those with osteoarthritis (OA). Regardless of diagnosis, days with higher than average negative interpersonal events were also were associated with increased next-day fatigue. Thus, female pain patients may have derived some immediate benefit from positive events in the form of reduced fatigue, but some women may also have incurred a delayed cost. Thus, we investigated whether the carry-over effects of changes in interpersonal events on fatigue generalize from women to men with RA.

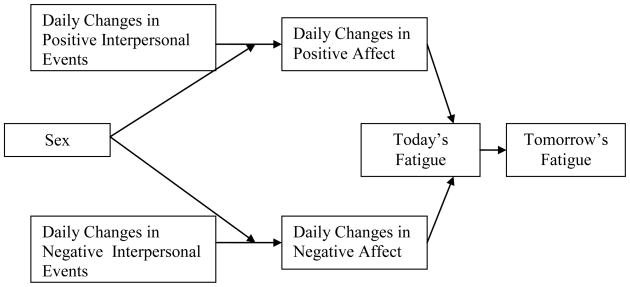

In the current study, we examined the within-person relations among positive and negative interpersonal events, positive and negative affect, and fatigue in RA patients, and assessed whether sex moderates these associations. Figure 1 depicts a model used to frame the three questions addressed in this study. First, are there sex differences in the relations between daily changes in positive and negative interpersonal events and same-day fatigue? Second, do positive and negative affect mediate the relations between changes in positive and negative interpersonal events and same-day fatigue for men and women? Finally, to what extent do the effects of daily positive and negative interpersonal events experienced on one day carry over to predict next-day fatigue for men and women?

Figure 1.

Model Depicting Hypothesized Relations Between Subject Sex, Changes in Daily Interpersonal Events, Positive and Negative Affect, and Fatigue.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited through flyers and advertisements from physician’s offices, VA hospital rheumatologists, senior citizen groups, the Arthritis Foundation membership, and the Phoenix metropolitan community. To be eligible for the study, participants were required to (a) be between 21 and 86 years old, and (b) have a physician-confirmed diagnosis of RA. In addition, participants were excluded if they were receiving a cyclical estrogen-replacement therapy.

The sample consisted of 228 participants (158 women, 70 men), all enrolled in the study between January 2001 and November 2004. A recent study from our group examining event-fatigue relations in women with diverse chronic pain problems included data from 89 of the women in the current study, but excluded data from the remaining 69 women because these participants had a co-morbid pain condition other than osteoarthritis (OA) or were missing data on variables relevant to that study19.

Procedure

All procedures employed in this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Arizona State University. Interested individuals contacted research staff members by phone and underwent a brief screening interview to determine eligibility. Eligible individuals provided written informed consent and permission for research personnel to contact their physicians to confirm their RA diagnosis. Participants then received an initial packet of questionnaires via mail that contained items assessing demographic data and personality characteristics. After they completed and returned the initial questionnaires, participants first received a set of 30 daily diaries and 30 pre-addressed, stamped envelopes by mail, and then received instructions regarding completion of the diaries from a staff member by phone. Participants were asked to complete a diary each night approximately 30 minutes prior to going to bed, and to place the completed diary in the mail the next day. Participants were paid up to $90 for returning the daily diaries (i.e., $2/diary plus $1/diary if 25 or more diaries were returned). Aggregating across participants, 94% of the diaries were completed, and of those completed diaries, 97.3% were received with a verified postmark. Of the diaries with a verified postmark, 80% were postmarked within 2 days of diary completion (allowing for weekend and holiday constraints on mail service).

Measures

Daily interpersonal events

The daily diaries included interpersonal events from the Inventory of Small Life Events (ISLE) for older adults 38. The inventory included 26 positive interpersonal events (e.g., “played a sport, game, or cards with friends”) pertaining to spouse/live-in partner (6), other family members (9), friends and acquaintances (7), and coworkers (4). In addition, the inventory included 22 negative interpersonal events (e.g., “criticized by friend/acquaintance”) pertaining to spouse/live-in partner (5), other family members (3), friends and acquaintances (7), and co-workers (7). Participants also were asked whether any “other” positive and negative events occurred during the day in social interactions with spouse or live-in partner, family members, friends and acquaintances, and co-workers. Daily sum scores were calculated by counting the total number of positive interpersonal events and the total number of negative interpersonal events.

Affect

Daily affect was assessed in the diaries using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; 32). Participants rated 10 positive and 10 negative affect terms. Participants rated how much they felt each positive and negative affect item during that day on a 5-point scale (1 = “Very slightly or not at all” to 5 = “Extremely”). Positive and negative affect summary scores were computed for each day by calculating the means for the ratings of all positive affect items and all negative affect items that were rated on that day. Within-person reliability estimates were computed by first transforming items into z-scores within each participant. The within-person Cronbach’s alpha was .86 for positive affect and .77 for negative affect.

Fatigue

Daily fatigue was assessed in the diaries by asking the participant, “What number between 0 and 100 describes your average level of fatigue today? A zero (0) would mean ‘no fatigue’ and a one hundred (100) would mean ‘fatigue as bad as it can be.’11. This fatigue rating is similar to one-item assessments employed in recent research examining fatigue in FM 33, 35. The validity of this single-item scale was probed by examining its correlation with the SF-36 Vitality subscale 31. For both sexes, fatigue scores were correlated −.57 with vitality scores.

Covariates

Several potential covariates were assessed on the initial questionnaire including age, education, income, employment status, marital/romantic relationship status, and general health. General health was assessed with a single item from the SF36, asking individuals to rate their health on a 5-point scale, ranging from poor to excellent31. Additionally, daily pain was examined as a covariate, via the following standard single item included in the diary assessment: ‘What number between 0 and 100 describes your average level of arthritis pain today? A zero (0) would mean ‘no pain’ and a one hundred (100) would mean ‘pain as bad as it can be’11.

Analytic strategy

Repeated daily measurements in our study resulted in up to 30 observations per diary variable for each person. Within-person scores were derived for measures of events, affect, and pain. For each daily diary variable of interest, we computed each person’s average score across the 30 days. Then for each person, we subtracted his or her mean from each of his or her daily scores, resulting in a set of up to 30 deviation scores for each variable of interest. For example, if a subject had an average pain rating across the 30 days of 50 and her rating of pain on day 1 was 60, her day 1 deviation score would be +10. These deviation scores, also termed person-centered scores, index day-to-day within-person change relative to an individual’s average level on the variable of interest. In the remainder of the article, we use the term “change” to refer to within-person deviation scores. The primary between-person predictor in the analyses was sex, coded such that female = 1 and male = 0.

We first conducted preliminary analyses to examine sex differences in demographic, physical health, and daily diary variables with t-test and chi-square comparisons. Then we assessed the within-person association between same-day negative interpersonal events and positive interpersonal events. For our main analyses, we tested whether 1) sex moderates the relations between changes in daily positive and negative events, and same-day fatigue; 2) whether changes in positive and negative affect mediate the event-fatigue relations; and 3) whether effects of events carry over to affect next-day fatigue. To probe significant sex by event interaction effects, we used the Aiken and West 1 procedure to plot the simple slopes for the association between within-person deviation scores and same-day fatigue (and affect) for each sex. All primary analyses were repeated, including age, education, employment status, income, marital status, and presence of a co-morbid pain condition (0=none, 1= one or more) as between-person covariates, and daily changes in pain as a within-person covariate; presence of co-morbid pain condition and daily changes in pain both predicted fatigue and so were retained in the final models. In models that predicted daily positive affect, daily negative affect was included as a covariate; conversely, in models that predicted daily negative affect, daily positive affect was included as a covariate.

The principal analyses for this study employed multilevel or hierarchical linear modeling. This method is designed to handle hierarchical nested data. In our study, the 30 daily diary reports are nested within people. Multilevel modeling is able to account for variation both within and between individuals, and is particularly useful when participants have varying amounts of missing data. The analyses were performed with SAS PROC MIXED software12, which furnishes parameters in the form of unstandardized maximum likelihood estimates (β coefficients). These coefficients serve as useful effect size estimations of magnitude and direction of changes in dependent variables associated with within-person changes in independent variables. For all analyses, we allowed intercepts to vary randomly, thus enabling us to generalize the findings to the population of persons from which the sample was drawn, and the population of observations from which their daily reports were samples. We also allowed the slope relating changes in pain to outcomes, and the slope relating the sex X positive events interaction to outcomes, to vary randomly when including these random effects improved the fit of the model. All same-day models included a first-order autoregressive variance-covariance matrix to account for the tendency of scores on variables to be highly correlated from one day to the next day.

The multilevel regression model predicting same-day fatigue included the following independent variables: 1) average pain level; 2) daily changes in positive events; 3) daily changes in negative events; 4) sex; and 5) sex X change in events interaction terms (to test for sex differences in event—fatigue relations). Covariates included the presence of a co-morbid pain condition and changes in level of pain. The same independent variables and covariates were included in models predicting positive and negative affect, purported mediators of event-fatigue relations, along with the alternate affect. The final model predicting next day’s fatigue was modified by including same-day’s fatigue as a predictor (to account for day-to-day covariation in fatigue).

Results

Demographic Characteristics

The sample had a mean age of 55.31 (SD = 13.23). Ninety percent of the participants were Caucasian and 64% were married or living with a romantic partner. Approximately 39% of the participants reported that they had graduated from college, and 36% indicated that they were currently employed. The average annual household income of the sample fell between $30,000 and $39,999. Participants estimated that they first noticed their RA symptoms a mean of 15.88 years earlier (SD = 14.31) and received a diagnosis of RA a mean of 13.44 years earlier (SD = 13.13). For the sample as a whole, the average daily fatigue rating was 32.85 (SD = 18.18) and the average daily pain rating was 35.18 (SD = 18.35) on a 0–100 rating scale (described below). Thirty percent of the sample had one additional chronic pain condition, and 24 % had two or more. The most common co-morbid pain condition was back pain (33%), followed by OA (31 %), and fibromyalgia (17%).

Means, standard deviations, and distributions for demographic characteristics and health-related variables by sex are shown in Table 1. Comparisons of the sexes yielded two differences: women were younger and more likely to be employed than were men. The sexes were equally likely to be Caucasian, married/partnered, and managing a co-morbid pain condition, and reported a similar level of education, income, years since RA diagnosis, and general health.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations by sex for demographics and physical health variables.

| Men (n=70) | Women (n=158) | t-value or (Chi-square) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61.26 (13.60) | 52.73 (12.24) | 4.71 | .0001 |

| % Caucasian | 91.4% | 89.2 | (.26) | .81 |

| % Married/Partnered | 68.6% | 62.7% | (.74) | .39 |

| Education | 5.79 (1.63) | 6.17 (1.47) | 1.76 | .08 |

| Income | 12.61 (4.03) | 13.23 (4.33) | .99 | .32 |

| % Employed | 25.7% | 41.4% | (5.14) | .03 |

| Years since RA Diagnosis | 15.27 (13.45) | 12.65 (12.95) | −1.37 | .17 |

| SF-36 General Health (1=poor to 5 =excellent) | 2.78 (.85) | 2.95 (.99) | 1.24 | .22 |

| % with co-morbid pain condition(s) | 51.5% | 56.1% | (.40) | .56 |

Note: RA= Rheumatoid Arthritis. Co-morbid pain conditions include osteoarthritis, back pain, fibromyalgia, scerloderma, gout, and lupus erythematosus.

Demographic Differences in Daily Diary Measures

Table 2 depicts means and standard deviations for main study variables by sex. Women reported more daily positive and negative interpersonal events than men, and were higher than men on positive affect, negative affect, fatigue, and pain. With regard to fatigue scores, a model that included no predictors (i.e., unconditional model) indicated that the proportion of variance in fatigue accounted for by differences between individuals was 58%. Consequently, 42% of the variance in fatigue occurred within individuals on a day to day basis. The proportion of within-person/total fatigue variance was similar for men (41%) and women (42%).

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations by sex for main study variables.

| Men | Women | t-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Positive Interpersonal Events |

4.27 (2.86) | 5.32 (3.10) | 12.81 | .0001 |

| Daily Negative Interpersonal Events |

0.76 (1.25) | 0.98(1.46) | 5.72 | .0001 |

| Daily Positive Affect (1 to 5 rating) |

2.61 (.81) | 2.74 (.94) | 5.13 | .0001 |

| Daily Negative Affect (1 to 5 rating) |

1.29 (0.45) | 1.33 (0.51) | 2.87 | .004 |

| Daily Fatigue (0 to 100 rating) | 29.55 (20.52) | 34.09 (23.80) | 7.30 | .0001 |

| Daily Pain (0 to 100 rating) | 33.34 (21.13) | 36.18 (23.77) | 4.54 | .0001 |

Note: Ns for these daily variables range from 1898 to 1928 for men, and from 4660 to 4705 for women.

The distribution of positive interpersonal events for men and women by type of relationship was as follows: spouse/live in partner (40% men and 30% women), other family members (28% men and 35% women), friends and acquaintances (27% men and 28% women), and co-worker (5% men and 7% women). For negative interpersonal events the distribution for men and women by type of relationship was as follows: spouse/live in partner (48% men and 34% women), other family members (14% men and 23% women), friends and acquaintances (20% men and 24% women), and co-worker (18% men and 19% women). Thus, spouses/partners account for a greater percentage of positive and negative events for men than for women and other family members account for a greater percentage of positive and negative events for women than men. Negative daily events were not significantly associated with same-day positive events, β = .04, t (6315) = 1.41, p > .16.

Prediction of Same-Day Fatigue

Sex as a Moderator of Event-Fatigue Relations

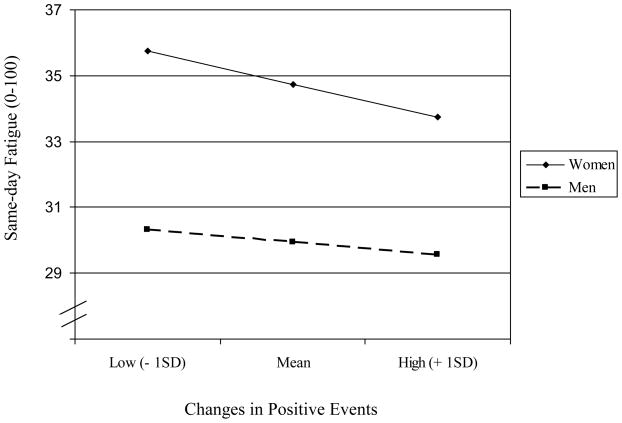

Table 3 displays the results of analyses examining whether changes in daily positive and negative events (relative to a person’s average level) predicted same-day fatigue, and whether these relations varied by sex, taking into account the presence of co-morbid pain conditions and changes in daily pain. Individuals with one or more comorbid pain conditions had higher levels of fatigue than did individuals with RA only (t = 5.21, p < .0001). Days with a greater than average level of pain (t = 20.74, p < .0001) and a greater than average number of negative interpersonal events (t = 3.12, p < .002) were associated with more same-day fatigue Furthermore, the association between changes in positive interpersonal events and same-day fatigue varied by sex (t = −2.01, p = .05). Figure 2 shows an inverse relation between changes in positive interpersonal events and same-day fatigue in women but not in men. On a day when they experienced one additional positive event, women reported approximately a 0.36 point lower score than their average on the 0–100 scale for fatigue, a benefit not evident in men. Finally, we included an interaction effect in the model to determine whether the association between changes in negative interpersonal events and same-day fatigue differed for men and women, but the effect was not significant (t = .20, = p > .84). Therefore, it was dropped from the final model. Compared to an unconditional model, a model that included changes in daily pain accounted for approximately 28% of the pooled within-person variance in daily fatigue, and an additional 2% was explained by including changes in positive and negative events, and the sex X positive events interaction.

Table 3.

Sex, changes in daily events, and their interaction in the prediction of same-day fatigue.

| Predictor Variables | β | t | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 4.30 | 1.75 | .09 |

| Co-morbid Pain Condition | 11.82 | 5.21 | <.0001 |

| Δ Pain | 0.47 | 20.74 | <.0001 |

| Δ Positive Events | −0.13 | −0.90 | .37 |

| Δ Negative Events | 0.44 | 3.12 | .002 |

| Δ Positive Events × Female | −0.36 | −2.01 | .05 |

Note: Pain and event scores are person-centered. Pain and interaction terms were modeled as random effects. Fatigue was significantly higher in individuals with a co-morbid pain condition relative to those without one. Fatigue was also higher for individuals on days when they experienced greater than their average number of negative events, and lower on days when they experienced greater than their average number of positive events. The relation between positive events and fatigue was stronger in women than in men.

Figure 2.

Interaction between Change in Positive Interpersonal Events and Being Female on Same-day Fatigue.

Affect as Mediators in Event-Fatigue Relations

We next examined whether changes in daily positive and negative affect mediated the relations between changes in events and same-day fatigue. To establish a link between events and the purported mediators, we tested whether changes in events predicted same-day affect scores, controlling for the alternate affect, daily pain, and education level. Individuals with a comorbid pain condition had lower levels of positive affect than those with RA only (t = −2.78, β = −.259, p = .006). In addition, days with more positive interpersonal events (t = 9.35, β = .053, p <.0001), less pain (t=−9.00, β = −.007, p < .0001), and lower negative affect (t = −17.70, β = −.343, p < .0001) than an individual’s average were associated with higher positive affect. The main effect for positive events was qualified, however, by a significant interaction between changes in daily positive interpersonal events and being female (t = 3.18, β = .024, p = .002). Evaluation of the interaction revealed that changes in positive interpersonal events are more strongly associated with increased positive affect in women as compared to men. An increase of one positive event above a person’s average was associated with a .05 point higher score on the 0–5 rating of positive affect average for all individuals, and women evinced an additional .02 point boost in positive affect per additional positive event compared to men. Approximately 9% of the pooled within-person variance in daily positive affect was explained by changes in pain, and an additional 15% was explained by positive and negative events and the interaction between sex and positive events.

A parallel analysis was conducted in which the dependent variable was same-day negative affect. Days with fewer negative interpersonal events (t = 10.66, β = .08, p < .0001), less pain (t = 5.86, β = .003, p < .0001), and more positive affect (t = −17.97, β = −.14, p < .0001) than a person’s average were associated with lower negative affect. In addition, the interaction between changes in negative interpersonal events and being female was significant (t = 2.15, β = .018, p = .04). Evaluation of the interaction revealed that the association between changes in daily negative interpersonal events and same-day fatigue was stronger in women relative to men. An increase of one negative event above a person’s average was associated with a .08 point higher score on the 0–5 rating of negative affect average for all individuals, and women evinced an additional .02 point increase in negative affect per additional negative event compared to men. Approximately 7.5 % of the pooled within-person variance in daily negative affect was explained by changes in pain, and an additional 15 % was explained by positive and negative events and the interaction between sex and negative events.

Thus, interpersonal events are more closely tied to affective experiences in women than in men. Days with many positive interpersonal events are more beneficial for women than men in terms of same-day positive affect and days with many negative interpersonal events were more detrimental for women than men with respect to same-day negative affect.

Our next step was to test the possibilities that (a) changes in positive affect mediate the changes in positive interpersonal events by sex interaction effect on same-day fatigue; and (b) changes in negative affect mediate the effect of changes in negative interpersonal events on same-day fatigue 3. To this end, we included affect scores together with event scores, sex, and the sex by positive event interaction effect (together with daily pain and comorbid pain condition as covariates) in a model predicting same-day fatigue. Once affect scores were included in the model, the change in positive interpersonal events by being female interaction effect was no longer significant (t = −1.20, p = .23). Similarly, the main effect of changes in negative interpersonal events was not significant (t = −0.31, p = .76). We examined two meditational pathways--(a) changes in positive interpersonal events by being female interaction term→ positive affect → same-day fatigue; and (b) changes in negative interpersonal event → negative affect → same-day fatigue using a z test 13. Both meditational paths were significant (positive affect z test = −3.64, negative affect z test =5.08; both ps < .0001).

Prediction of Next-Day Fatigue

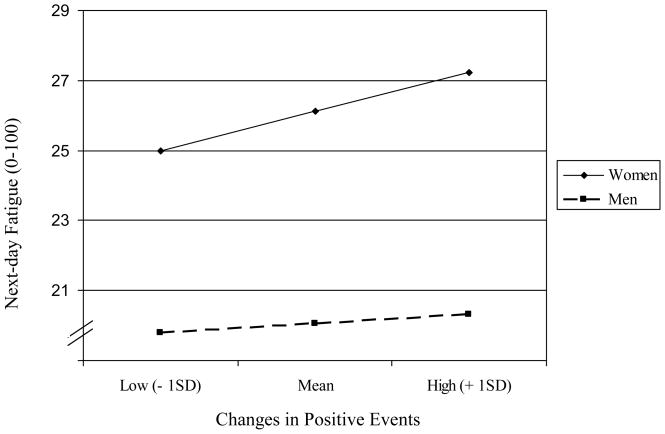

We next tested whether the event-fatigue relations that were apparent on the same day carried forward to the next day (see Table 4). Not surprisingly, same-day fatigue was a strong predictor of next-day fatigue (t = 18.57, p < .0001). As noted in the same-day findings, individuals with a comorbid pain disorder reported higher next-day fatigue than did RA-only individuals. Days with more than a person’s average level of pain (t = 3.32, p =.001) and number of negative interpersonal events (t = 3.26, p = .002) were associated with greater fatigue on the next day. The interaction between changes in positive interpersonal events and sex also was significant (t = 2.05, p = .04). Figure 3 shows the form of the changes in positive interpersonal events by sex interaction effect on next-day fatigue. In contrast to the findings for same-day fatigue, days with increased positive interpersonal events were followed the next day by increases in fatigue for women but not for men. For women, a day with one positive event more than their average was followed by an increase of 0.41 point on the fatigue scale on the following day. Approximately 6% of the pooled within-person variance in next-day fatigue was explained by same-day fatigue, and an additional 3 % was explained by changes in same-day pain. Changes in same-day positive and negative events and the sex by positive event interaction term accounted for an additional 1% of the variance.

Table 4.

Sex, changes in daily events, and their interaction in the prediction of next-day fatigue.

| Predictor Variables | β | T | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 2.67 | 1.52 | .13 |

| Co-morbid Pain Condition | 8.35 | 5.15 | < .0001 |

| Same-day Fatigue | 0.27 | 18.57 | <.0001 |

| Δ Pain | 0.07 | 3.32 | .001 |

| Δ Positive Events | 0.10 | 0.58 | .56 |

| Δ Negative Events | 0.55 | 3.26 | .002 |

| Δ Positive Events × Female | 0.41 | 2.05 | .04 |

Note: Pain and event scores are person-centered. Pain score was modeled as a random effect. Next-day fatigue was significantly higher in individuals with a co-morbid pain condition relative to those without one, and on days following a high fatigue level. Next-day fatigue was also higher for individuals following days when they experienced more than their average level of pain and greater than their average number of negative events. For women only, next-day fatigue was higher following days with greater than their average number of positive events.

Figure 3.

Interaction between Change in Positive Interpersonal Events and Being Female on Next-day Fatigue.

Finally, we conducted exploratory analyses to determine whether changes in same-day affect mediated the associations between same-day events and next-day fatigue. Specifically, we examined two meditational pathways—(a) changes in positive interpersonal events by being female interaction term→ positive affect → next-day fatigue; and (b) changes in negative interpersonal event → negative affect → next-day fatigue. The positive affect meditational path was not significant (z = .82, p = .42). In contrast, negative affect partially mediated the association between changes in negative interpersonal events and next day fatigue (z = 2.28, p = .01).

Discussion

Our study is the first one to explicitly examine sex differences in the relations between daily events, affect, and fatigue in RA, and findings point to some small but consistent differences between men and women. Days with more frequent positive events were related to lower levels of same-day fatigue and higher levels of next-day fatigue for women but not for men. Thus, women experienced less fatigue on a day when they reported more than their usual number of positive events, but suffered a “fatigue hangover” on the next day. Women in the sample had higher pain levels across the 30 days of diaries than did men, and change in daily pain showed a strong association with fatigue, accounting for 28% of the within-person changes. Yet the sex difference in the link between positive events and fatigue was sustained in analyses controlling for changes in pain. The current findings extend those detailed in an earlier report from our research group documenting the same-day and next-day relations between positive events and fatigue in women with chronic pain from RA or FM19, by including additional evidence that the pattern observed in women does not hold for men. Men do not seem to get any respite from fatigue tied to positive events on the same day, nor do they show any increase in fatigue on the following day. For men with RA, fatigue is largely unrelated to their daily positive interpersonal events. The current findings mirror those reported in a recent qualitative study of RA patients, which suggested that women, relative to men, perceive stronger relations between psychosocial factors, including social contacts and work-life balance, and their fatigue levels 17.

We examined whether positive affect served as a mediator of the sex difference in the relation between positive events and fatigue, and found that on days when they experienced increased positive events, women reported a bigger boost in positive affect than did men, which explained some of their decreased same-day fatigue. These findings from end-of-day diaries contrast with those derived from within-day diaries of healthy adults showing that men and women report similar changes in positive affect shortly following positive social interactions that occur throughout the day e.g., 7, 15. One possible explanation for the discrepant findings rests with the timing of assessment of positive interpersonal events and affect. The sexes may experience a similar boost in positive affect in the immediate aftermath of a pleasant interpersonal exchange, but women may derive a greater boost than men from recalling the accumulation of recently experienced positive events 28. A second possibility is that sex differences in event-mood associations vary between healthy and chronically ill individuals. A pain condition itself may serve as a chronic stressor that is distinct for men and women 30, altering the associations between positive interpersonal events and affect.

Our findings linking everyday stressors with fatigue in RA are consistent with those reported previously in the literature 24, and demonstrate that the relation between negative events and fatigue is mediated by negative affect. Increases in negative interpersonal events were associated with increases in same-day fatigue and predicted next-day fatigue to a similar degree for both men and women. However, days with higher than average negative events were associated with greater increases in negative affect for women than for men. Thus, sex differences in event-affect relations were evident for both positive and negative events, suggesting that women with RA are more emotionally responsive to all aspects of their social environments than are their male counterparts.

What can account for the sex differences in the day-to-day relations between positive events and fatigue? We proposed that it might be due to the greater investment in relationships by women relative to men. However, the lack of a sex by change in negative interpersonal event interaction effect on fatigue argues against this explanation. A second possibility is that the experience of fatigue is more tightly bound to external cues among women than men, consistent with Pennebaker and Roberts’ notion that women may use more external cues to alert them to current internal states compared to men 20. In line with this account, daily increases in positive events were more strongly related not only to fatigue but also to positive affect for women than for men.

Our observation that one day’s increase in positive events carried over to predict increased next-day fatigue in women but not men also deserves comment. It is possible that positive events lead to a greater expectation of sustained social engagement for women versus men with RA, leaving them insufficient opportunity to restore their energy reserves. In supplementary exploratory analyses, one day’s positive events were related to next-day’s positive events to a similar degree for men and women (data not shown). Thus, it is unlikely that actual ongoing social demands account for the carryover effects of positive events on fatigue we observed among women compared to men. A second account of the sex differences in carryover effects holds that there may be neurophysiological differences that result in more pronounced event-fatigue associations in women. For example, pro-inflammatory cytokines are related to increased fatigue in healthy adult and RA samples 5, 18. Although women and men show similar increases in pro-inflammatory cytokine production during psychological tasks, women show a reduced capacity to terminate production during post-task recovery 22. Thus, to the extent that positive events provoke increased inflammation in RA patients, women may experience more sustained inflammation-related fatigue compared to men. Future work that includes frequent repeated assessment of inflammatory markers together with interpersonal events and fatigue will be required to determine whether this explanation is a valid one.

Our findings are in line with previous reports linking aggregate measures of positive and negative aspects of interpersonal relationships with fatigue in RA 9, 14. Nevertheless, changes in daily events accounted for a small proportion of the within-person variation in fatigue day to day in the current study, indicating that other social, psychological, and physiological factors must play a role. One such factor is pain level, which accounted for a large portion of the day to day changes in fatigue 9, 26. Although evidence to date is limited, some findings suggest that sleep quality26, physical activity 4, 16, and illness cognitions (e.g., focusing on adverse aspects of functioning) 6 also deserve more empirical attention as determinants of daily fatigue.

Some important limitations constrain the interpretation of the current findings. First, because the data are observational, we can conclude only that events are related to affect and to fatigue, not that they cause them. Similarly, our meditational analyses of same-day data are consistent with, but do not establish, an event → affect → fatigue causal sequence. Second, the sample included adults with an RA diagnosis who had experienced symptoms for an average of nearly 16 years. The sample was also mostly Caucasian and middle-aged. Whether the current findings generalize to more recently diagnosed or ethnically diverse RA patients, children with RA, or non-RA chronic pain patients remains to be determined. Third, our one-item measure of fatigue could not capture the multidimensional nature of the fatigue experience 25. Finally, the data are based on participants’ reports of their experiences at the end of each day. More frequent sampling and inclusion of additional methods of assessment (e.g., physiological markers) could have helped us to elaborate the mechanisms underlying the event-fatigue relations we observed.

Our study also had some notable strengths. Including a diary measure with items that tap the occurrence of specific, discrete events rather than ratings of perceived stress or enjoyment likely reduced the bias in recall that can affect reporting of interpersonal events. Moreover, reports were collected across 30 days, yielding reliable estimates of the day-to-day covariation between events and fatigue and allowing us to test both same-day and next-day associations. The assessment of diverse events provided the opportunity to consider the independent relations between positive as well as negative interpersonal events and RA symptoms.

Fatigue is the most bothersome symptom reported by many RA patients, and one that has significant implications for functional health and quality of life 34. Because we observed a small association between day-to-day changes in daily interpersonal events and fatigue, it is reasonable to question whether the current findings are meaningful for RA patients’ quality of life. After all, one additional positive interpersonal event per day is related to only about a .4 point decrease in same-day fatigue on a 0–100 point scale. On the other hand, the events we assessed were quite minor, including such momentary experiences as kissing one’s spouse or receiving a compliment. An increase in the experience of these kinds of interpersonal “moments” would not be expected to create immediate, large magnitude changes in fatigue akin to those observed after weeks or months of intensive pharmacologic or behavioral treatment 6, 21. Rather, these events, albeit small, occur on a daily basis, and their potential impact on fatigue thus is more likely to accrue slowly over time.

Our findings highlight the dynamic relations among social events, affect, and fatigue in RA, and point to important similarities and differences in those dynamics for men and women. They further suggest that the development of effective self-management strategies for fatigue will require more complex models that capture the interplay of psychological and social factors in the day-to-day lives of individuals with RA. In future research, it will be important to elucidate the different mechanisms by which changes in positive events influence same-day and next-day fatigue of women with RA. Our findings indicate that while positive affect helps us to understand why days with higher than average positive interpersonal events are associated with less same-day fatigue for women, it does not explain the carryover effects of positive events to next-day fatigue. Identification of mechanisms may inform efforts to develop treatment plans that enable patients to obtain a same-day energy boost from pleasant events without experiencing a next-day energy slump. In the mean time, our findings suggest that with respect to fatigue, increases in positive interpersonal events have mixed effects for women and do not benefit men. In contrast, negative interpersonal events are associated with elevated same- and next-day fatigue for men and women alike. Consequently, clinicians should consider assessing whether RA patients have re-occurring negative social exchanges and then assist RA patients in developing strategies to reduce exposure to those events.

Perspective

This article presents an examination of sex differences in the links between changes in daily interpersonal events and fatigue in chronic pain patients. The findings can help clinicians target the psychosocial factors that potentially can ameliorate their patients’ experience of fatigue.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Musculoskeletal, Immune, and Skin Disease (R01 AR41687, Alex Zautra, PI) and a grant from the Arthritis Foundation (Howard Tennen, PI).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Mary C. Davis, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University

Morris A. Okun, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University

Denise Kruszewski, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University

Alex J. Zautra, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University

Howard Tennen, University of Connecticut Health Center

References

- 1.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Sage; Newbury Park: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonucci TC, Akiyama H. An examination of sex differences in social support among older men and women. Sex Roles. 1987;17:737–749. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belza BL, Henke CJ, Yelin EH, Epstein WV, Gilliss CL. Correlates of fatigue in older adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Nurs Res. 1993;42:93–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis MC, Zautra AJ, Younger J, Motivala SJ, Attrep J, Irwin MR. Chronic stress and regulation of cellular markers of inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis: Implications for fatigue. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evers AWM, Kraaimaat FW, van Riel PLCM, de Jong AJL. Tailored cognitive-behavioral therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis for patients at risk: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2002;100:141–153. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00274-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feldman-Barrett L, Robin L, Pietromonaco PR, Eyssell KM. Are women the “more emotional” sex?: Evidence from emotional experiences in social context. Cogn Emot. 1998;12:555–578. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gable SL, Reis HT, Impett EA, Asher ER. What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;87:228–245. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huyser BA, JCP, Thoreson R, Smarr KL, Johnson JC, Hoffman R. Predictors of subjective fatigue among individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:2230–2237. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199812)41:12<2230::AID-ART19>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Igarashi T, Takai J, Yoshida T. Gender differences in social network development via mobile phone text messages: A longitudinal study. J Soc Pers Relat. 2005;22:691–713. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen MP, Karoly P, Braver S. The measurement of clinical pain intensity: A comparison of six methods. Pain. 1986;27:117–126. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD. SAS System for Linear Mixed Models. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacKinnon DP. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. Erlbaum; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mancuso C, Rincon M, Sayles W, Paget SA. Psychosocial variables and fatigue: A longitudinal study comparing individuals with rheumatoid arthritis and healthy controls. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1496–1502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthews KA, Raikkonen K, Everson SA, Flory JD, Marco CA, Owens JF, Lloyd CE. Do the daily experiences of healthy men and women vary according to occupational prestige and work strain? Psychosom Med. 2000;62:346–353. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200005000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neuberger GB, Press AN, Lindsley HB, Hinton R, Cagle PE, Carlson K, Scott S, Dahl J, Kramer B. Effects of exercise on fatigue, aerobic fitness, and disease activity measures in persons with rheumatoid arthritis. Research in Nursing & Health. 1997;20:195–204. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199706)20:3<195::aid-nur3>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nikolaus S, Bode C, Taal E, van de Laar MAFJ. New insights into the experience of fatigue among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2009 doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.118067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papanicolaou DA, Wilder RL, Manolagas SC, Chrousos GP. The Pathophysiologic Roles of Interleukin-6 in Human Disease. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:127–137. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-2-199801150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parrish B, Zautra AJ, Davis MC. The role of positive and negative interpersonal events on daily fatigue in women with fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and osteoarthritis. Health Psychol. 2008;27:694–702. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pennebaker JW, Roberts T. Toward a his and hers theory of emotion: Gender differences in visceral perception. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1992;11:192–212. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollard LC, Choy EH, Gonzalez J, Khoshaba B, Scott DL. Fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis reflects pain, not disease activity. Rheumatol. 2006;45:885–889. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rohleder N, Schommer NC, Hellhammer DH, Engel R, Kirschbaum C. Sex Differences in Glucocorticoid Sensitivity of Proinflammatory Cytokine Production After Psychosocial Stress. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:966–972. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200111000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rupp I, Boshuizen HC, Jacobi CE, Dinant HJ, van den Bos GAM. Impact of fatigue on health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2004;51:578–585. doi: 10.1002/art.20539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schanberg LE, Sandstrom MJ, Starr K, Gil KM, Lefebvre JC, Keefe FJ, Affleck G, Tennen H. The relationship of daily mood and stressful events to symptoms in juvenile rheumatic disease. Arthritis Care Res. 2000;13:33–41. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200002)13:1<33::aid-art6>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smets EMA, Garssen B, Bonke B, De Haes JCJM. The multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:315–325. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00125-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stone AA, Broderick JE, Porter LS, Kaell AT. The experience of rheumatoid arthritis pain and fatigue: Examining momentary reports and correlates over one week. Arthritis Care & Research. 1997;10:185–193. doi: 10.1002/art.1790100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tack BB. Fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: Conditions, strategies, and consequences. Arthritis Care Res. 1990;3:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Todd BK, Anjali M, William EB, Jeffrey JF. Gender Differences in Gratitude: Examining Appraisals, Narratives, the Willingness to Express Emotions, and Changes in Psychological Needs. Journal of Personality. 2009;77:691–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Treharne GJ, Kitas GD, Lyons AC, Booth DA. Well-being in Rheumatoid Arthritis: The Effects of Disease Duration and Psychosocial Factors. J Health Psychol. 2005;10:457–474. doi: 10.1177/1359105305051416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Unruh AM. Gender variations in clinical pain experience. Pain. 1996;65:123–167. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ware JE, Sherbournce CD. The MOS 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) Medical Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolfe F. The relation between tender points and fibromyalgia symptom variables: Evidence that fibromyalgia is not a discrete disorder in the clinic. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:268–271. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.4.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolfe F, Hawley DJ, Wilson K. The prevalence and meaning of fatigue in rheumatic disease. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1407–1417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yunus MB, Arslan S, Aldag JC. Relationship between body mass index and fibromyalgia features. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 2002;31:27–31. doi: 10.1080/030097402317255336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zautra AJ, Affleck GG, Tennen H, Reich JW, Davis MC. Dynamic Approaches to Emotions and Stress in Everyday Life: Bolger and Zuckerman Reloaded With Positive as Well as Negative Affects. J Pers. 2005;73:1511–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2005.00357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zautra AJ, Fasman R, Parish BP, Davis MC. Daily fatigue in women with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia. Pain. 2007;128:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zautra AJ, Guarnaccia CA, Dohrenwend BP. Measuring small life events. Am J Community Psychol. 1986;14:629–655. doi: 10.1007/BF00931340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]