Abstract

The authors' experience with the supraclavicular approach for the treatment of patients with primary thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) and for patients with recurrent TOS or iatrogenic brachial plexus injury after prior transaxillary first rib resection is presented. The records of 33 patients (34 plexuses) with TOS who presented for evaluation and treatment were analyzed. Of these, 12 (35%) plexuses underwent surgical treatment, and 22 (65%) plexuses were managed non-operatively. The patients who were treated non-operatively and had an adequate follow-up (n = 11) were used as a control group. Of the 12 surgically treated patients, five patients underwent primary surgery; four patients had secondary surgery for recurrent TOS; and three patients had surgery for iatrogenic brachial plexus injury. All patients presented with severe pain, and most of them had neurologic symptoms. All nine (100%) patients who underwent primary surgery (n = 5) and secondary surgery for recurrent TOS (n = 4) demonstrated excellent or good results. On the other hand, six (54%) of the 11 patients from the control group had some benefit from the non-operative treatment. Reoperation in three patients with iatrogenic brachial plexus injury resulted in good result in one case and in fair results in two patients; however, all patients were pain-free. No complications were encountered. Supraclavicular exploration of the brachial plexus enables precise assessment of the contents of the thoracic inlet area. It allows for safe identification and release of all abnormal anatomical structures and complete first rib resection with minimal risk to neurovascular structures. Additionally, this approach allows for the appropriate nerve reconstruction in cases of prior transaxillary iatrogenic plexus injury.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11552-009-9253-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Supraclavicular approach, Thoracic outlet syndrome, Neurogenic TOS, Nonspecific-type TOS, First rib resection, Iatrogenic brachial plexus injury

Introduction

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) refers to compression of the neurovascular structures at the superior aperture of the thorax [17, 20, 35]. Controversies exist concerning its causes, diagnosis, and treatment despite years of intense study of hundreds of patients [6, 7, 11, 21, 30, 32]. Although early investigators concentrated on the vascular manifestations of the disorder [1], more recent investigators think that the neural compression may be the source of many of the complaints [16, 18]. The brachial plexus (82%), subclavian vein (14%), and subclavian artery (4%) are affected [24]. Diagnosis and treatment of TOS involves neurologists, family physicians, reconstructive surgeons, physiatrists, vascular surgeons, thoracic surgeons, neurosurgeons, and sometimes psychiatrists.

Huang and Zager [17] divided patients with TOS into three groups: (1) compression of the brachial plexus, also called neurogenic TOS; (2) compression of the subclavian vessels (either artery or vein), also called vascular TOS; and (3) nonspecific-type TOS, sometimes referred to as the disputed or common type of TOS, consisting of poorly defined chronic pain syndrome with features suggestive of brachial plexus involvement. In some cases, the neurological and vascular components may coexist. The neurogenic type of TOS is seen clinically more often than the vascular TOS [33]. The nonspecific-type TOS refers to a large group of patients with unexplained pain in the arm, scapular area, and cervical region.

The management of TOS can be both non-operative and operative. Non-operative management includes modification of behavior by avoiding provocative activities and arm positions, in addition to individually tailored physical therapy programs that strengthen the muscles of the pectoral girdle and help to restore normal posture [34].

The indications for surgical treatment and the choice of the correct type of procedure still are a subject for discussion because of the frequency of recurrence and complications. Also, the methodology for evaluation of the results needs unification. Indications for surgery include: (1) intractable pain, (2) failure of a carefully supervised physical therapy program, (3) neurological deficit, (4) impending vascular catastrophe, and (5) completed and successful initial treatment of subclavian vein thrombosis [21].

Surgical options include first rib resection through a transaxillary approach [4, 7, 20–22, 27] and decompression with neurolysis of the involved regions of the brachial plexus, especially the C7, C8, and T1 nerve roots through a supraclavicular approach [2, 8, 29] (supraclavicular “neuroplasty” [29]). The first rib with the compressive elements may also be removed using the supraclavicular approach which enables careful evaluation of the brachial plexus [17, 21]. This approach, however, requires a thorough knowledge of the brachial plexus, and it does involve some careful retraction of the neural elements. Urschel [32, 33] suggested a posterior thoracoplasty approach for brachial plexus neurolysis and dorsal sympathectomy for recurrent TOS. Dorsal sympathectomy may also be performed through any of the above incisions for sympathetic maintained pain syndrome, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, causalgia, and Raynaud's phenomenon and disease [32].

The purpose of this study is to present the authors' experience with the supraclavicular approach for the treatment of the primary thoracic outlet syndrome and for patients who presented with recurrent TOS or had iatrogenic brachial plexus injury that took place during transaxillary first rib resection elsewhere.

Materials and Methods

Patient Population

The medical records of 33 patients (34 plexuses) with thoracic outlet syndrome who presented in our center for evaluation and/or treatment, from October 1983 to June 1999, were analyzed. Of these, 12 (35%) plexuses underwent surgical treatment, and 22 (65%) plexuses were managed non-operatively. The occupation and demographic data for all patients are presented in Table 1. One patient had bilateral TOS but underwent surgery only on his left side.

Table 1.

Patients’ demographics (all cases, n = 34).

| Demographic data | Surgery | Non-surgery | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 36.9 ± 11.5 (range, 21–55) | 39.7 ± 9.1 (range, 24–56) | ||

| Duration of symptoms (months) | 30.08 ± 21.0 (range, 6–68) | 20.7 ± 17.1 (range, 5–72) | ||

| No. of plexuses (n = 12) | Percent, % | No. of plexuses (n = 22) | Percent, % | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 7 | 58 | 11 | 50 |

| Male | 5 | 42 | 11 | 50 |

| Occupation | ||||

| Manual | 6 | 50 | 11 | 50 |

| Office | 2 | 17 | 4 | 18 |

| Sport | 1 | 8 | 1 | 5 |

| Student | 1 | 8 | 1 | 5 |

| Other | 2 | 17 | 5 | 23 |

The etiology of TOS in all patients is presented in Table 2. An evaluation of the cause of TOS found that 13 (38%) of the cases had incidence of trauma preceding the onset of symptoms. Motor vehicle accidents accounted for 21% of all causes of TOS. One patient had TOS secondary to malunion of the fractured clavicle and another patient developed TOS when treated for radiation after mastectomy. Nontraumatic TOS was found in nine (26%) of cases. Eleven (32%) of the cases had job-related TOS and had open workers' compensation claims.

Table 2.

Etiology of TOS (all cases, n = 34).

| Surgery | Non-surgery | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature of TOS onset | No. of plexuses (n = 12) | Percent, % | No. of plexuses (n = 22) | Percent, % | No. of plexuses (n = 34) | Percent, % |

| Traumatic | ||||||

| Motor vehicle accident | 2 | 17 | 5 | 23 | 7 | 21 |

| Industrial | 1 | 8 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 9 |

| Other | 1 | 8 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 9 |

| Not traumatic | ||||||

| Repetitive motion | 1 | 8 | 6 | 27 | 7 | 21 |

| Idiopathic | – | 0 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 6 |

| Recurrent | 4 | 33 | 5 | 23 | 9 | 26 |

| Iatrogenic | 3 | 25 | – | 0 | 3 | 9 |

Twelve (35%) of patients (i.e., more than one third of the patients that were evaluated), had previously undergone transaxillary first rib resection in other centers. Of these, nine patients had recurrent TOS, and three of them had iatrogenic complications from the surgery for which they subsequently were referred for consultation to the senior author.

The current study was conducted under the guidelines and the approval of the institutional review board committee of Eastern Virginia Medical School.

Patient Evaluation

Clinical evaluation included a detailed history and physical examination. At the initial consultation, the patient's symptoms were recorded and a complete clinical examination of the neck, shoulder, and upper extremity was performed, including muscle grading according to the British Medical Council Grading System. Grip strength was measured using a Jamar dynamometer (Preston Corp, Clifton, NJ), and key pinch strength was measured using a Jamar pinch gauge. Values were compared with the contralateral side, and the differences were expressed as a ratio. A complete sensory evaluation was performed, including light touch, cold and hot sensation, and static two-point discrimination. Each patient underwent provocative tests such as Adson's, Wright's, and Roos to evaluate neural and vascular compression. Pain level was measured using a visual analog scale, 0 to 10, with 0 being no pain and 10 representing maximal pain.

Routine diagnostic modalities included X-rays of the cervical spine, chest, and shoulder for differential diagnosis [23]. Magnetic resonance imaging of the neck was ordered in selected cases to rule out the presence of non-TOS conditions [9]. Electromyography and nerve conduction studies were employed in all patients to estimate conduction of the elements of the brachial plexus across the thoracic inlet, with emphasis in the ulnar and median nerves across the axilla, elbow, and wrist in order to rule out additional entrapment neuropathies, which may have co-existed in the upper extremity (double crush syndrome) [25, 36]. Findings of the clinical examination and electrophysiological studies of the surgical and nonsurgical groups are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Findings of clinical examination and electrophysiological studies (all cases, n = 34).

| Clinical examination | Surgery | Non-surgery | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of plexuses (n = 12) | Percent, % | No. of plexuses (n = 22) | Percent, % | No. of plexuses (n = 34) | Percent, % | |

| Symptoms | ||||||

| Pain | 12 | 100 | 19 | 86 | 31 | 91 |

| Muscle weakness | 10 | 83 | 20 | 91 | 30 | 88 |

| Sensation decrease | 8 | 67 | 15 | 68 | 23 | 68 |

| Provocative tests | ||||||

| Neural compression | 8 | 67 | 14 | 64 | 22 | 65 |

| Arterial compression | 6 | 50 | 12 | 55 | 18 | 53 |

| Electrophysiological studies | ||||||

| Positive | 8 | 67 | 14 | 64 | 22 | 65 |

| Negative | 4 | 33 | 8 | 36 | 12 | 35 |

Surgical Treatment

Twelve patients who had intractable pain and/or neurological symptomatology, as well as patients with recurrent TOS or complications following prior surgery for TOS elsewhere, were offered and accepted surgical treatment. Of note, pain was a significant complaint in all 12 (100%) patients. All operative procedures were carried out by the senior author (J. K. T.). Surgical treatment included exploration of the entire supraclavicular brachial plexus, neurolysis, removal of fibrotic bands, scalenectomy, primary first rib resection (primary TOS), and resection of remnants of first rib and overlooked cervical ribs (secondary TOS). In cases of iatrogenic brachial plexus injury or intercostobrachial nerve injury caused by prior transaxillary approach for TOS or intercostobrachial nerve injuries, the appropriate nerve reconstruction procedure was performed.

Surgical Technique

After adequate general endotracheal anesthesia with the patient in the supine position, the supraclavicular and infraclavicular area were prepped and draped in a standard fashion. A big roll was placed under the cervical and thoracic spine, and the head was turned in the opposite direction. An S-shaped incision was made along the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and along the proximal third of the clavicle. The brachial plexus was exposed in the usual fashion [31], using atraumatic techniques, and microstimulation took place prior to any mobilization of its elements. The anterior scalene muscle was divided off from its insertion into the first rib and mobilized cranially over 3–4 cm; a segment of the muscle was excised. The first rib was carefully exposed (primary TOS), and the periosteum and muscle tissue was elevated off the rib while the pleura was retracted posteriorly and inferiorly using a blunt retractor. Then, the plexus was carefully retracted, and the middle scalene muscle was identified. Its muscle fibers were dissected off of the posterior portion of the first rib, and again, the pleura was retracted away with a blunt retractor. Using Kerrison punches, the first rib was transected anteriorly and posteriorly, and then retraction on the rib, intercostal muscle fibers, and scalene muscle fibers were removed to permit complete removal of an approximately 8–10-cm segment of the first rib. Utilizing bone Rongeurs, as much of the anterior and posterior remnants of the first rib were removed leaving a wide open space below the clavicle. Pleural injury was avoided. Prior to removing the rib, intraoperative abduction and external rotation maneuver of the upper extremity brought the clavicle inferiorly and posteriorly with severe compression of the vascular and neural elements. Following the first rib removal, executing the same maneuver of abduction and external rotation, it was certain that there was no residual compression of the vascular and neural structures.

Following first rib resection, neurolysis of the brachial plexus was performed under the operative microscope. Vessel loops were placed around the nerve roots, and special care was taken to remove any bands or other soft tissue that might be compressing the roots or lower trunk. The extent of microneurolysis was based on the patient's symptoms, the preoperative assessment, and the intraoperative findings. Each root, trunk, and cords and divisions of the supraclavicular plexus were inspected under high magnification for signs of fibrosis, palpated for softness or hardness, and accordingly decompressed from the entrapping hypertrophic epineurial sheath. The microneurolysis commenced with simple epineuriotomy and progressed, as needed, to interfascicular scar excision (two cases). The goal was to restore “softness” in the plexus elements and to reach normal-looking neural tissue both proximally and distally. The level of brachial plexus compression in all cases is shown in Table 4. Neural compression to the entire plexus (C5-T1) was evident in eight (67%) cases.

Table 4.

Level of brachial plexus compression in patients who had surgical treatment (n = 12).

| Level | Surgery | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of plexuses (n = 12) | Percent | |

| C5,C6,C7 | 1 | 8 |

| C7,C8,T1 | 2 | 17 |

| C8,T1 | 1 | 8 |

| C5–T1 | 8 | 67 |

In all cases, microneurolysis of the entire plexus was performed. In one case, nerve reconstruction of the lower trunk with interposition nerve grafts was required, as a large neuroma was present which needed to be excised as there was no fascicular continuity and the perineurial continuity was lost.

All surgeries were completed uneventfully. There were no complications after the procedures for any patient.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between preoperative and postoperative motor and sensory data were performed with paired t test; and for pain data, Wilcoxon signed rank test was used. The small sample size limited the power of our study to detect differences among the postoperative groups. All the analysis was performed in SAS 9.1.3 (Cary, NC). Two-tailed p values of < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

Results were assessed according to Derkash's classification which was disseminated by Wood [37]: “excellent” result: no pain, easy return to preoperative professional and leisure daily activities; “good” result: intermittent pain well tolerated, possible return to preoperative professional and leisure daily activities; “fair” result: intermittent pain with bad tolerance, difficult return to preoperative professional and leisure daily activities; and “poor” result: symptoms not improved or aggravated.

Non-operative Treatment

Twenty-two patients were treated with physical therapy and nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs. Of these, 11 (50%) patients were lost to follow-up. The remaining 11 patients were followed up at an average period of 13.2 ± 3 months (range, 12 to 22 months). Although, the non-operative managed group suffers from a high rate of “lost to follow-up”, this group of patients who had an adequate follow-up (n = 11) was used as a control group. Of note, as in the surgically treated group (n = 12), four of 11 patients had previously undergone unsuccessful transaxillary first rib resection elsewhere. No iatrogenic brachial plexus injury existed among the cases. At the final follow-up, two patients had permanent relief of symptoms (excellent result), and four patients had temporary relief with reduction of symptoms of TOS (good result). The remaining five patients had no relief or improvement (fair or poor result) and were offered surgical treatment; however, they decided not to have surgery. The categorical results of the control group and the surgically treated group, pre- and postoperative measurements and statistical differences are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of the control group (n = 11) and the surgically treated group (n = 12).

| Surgery (n = 12) | Non-surgery (control, n = 11) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 36.9 ± 11.5 (range, 21–55) | 38.1 ± 8.0 (range, 24–50) | ||||

| Follow-up (months) | 36.1 ± 37 (range, 16–148) | 13.2 ± 3 (range, 12–22) | ||||

| Pre-op | Post-op | P | Pre-op | Post-op | P | |

| Outcome[27] | ||||||

| Excellent | 5 (42%) | 2 (18%) | ||||

| Good | 5 (42%) | 4 (36%) | ||||

| Fair | 1 (8%) | 1 (9%) | ||||

| Poor | 1 (8%) | 4 (36%) | ||||

| VAS | 7.33 ± 1.9 | 2.41 ± 1.6 | <0.001* | 6.81 ± 1.2 | 5.63 ± 2.3 | 0.078 |

| Mean grip strength ratio | 0.37 ± 0.31 | 0.56 ± 0.4 | 0.0398* | 0.45 ± 0.3 | 0.48 ± 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Mean pinch strength ratio | 0.48 ± 0.34 | 0.56 ± 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.59 ± 0.2 | 0.61 ± 0.3 | 0.51 |

| s2PD–ulnar nerve | 10.1 ± 7.4 | 7.04 ± 5.4 | 0.08 | 8.3 ± 7.1 | 8.6 ± 7.5 | 0.87 |

| s2PD–median nerve | 4.0 ± 2.0 | 3.45 ± 1.4 | 0.25 | 6.9 ± 4.7 | 7.2 ± 4.5 | 0.62 |

*Significant difference

VAS visual analog scale, s2PD static two-point discrimination

Surgical Treatment

Twelve patients underwent surgical treatment. The follow-up period ranged from 16 to 148 months (mean, 36.1 ± 37 months). Overall, ten (84%) of 12 patients achieved excellent or good results. The surgical outcomes among the various groups (A, B, and C) and detailed data for these patients are presented in Tables 6 and 7. Between the preoperative measurements and final follow up, patient pain levels (visual analog scale) were significantly reduced from 7.33 ± 1.9 to 2.41 ± 1.6 (Wilcoxon signed rank test, p < 0.001). As well, average grip strength ratio significantly increased from 0.37 ± 0.31 preoperatively to 0.56 ± 0.4 postoperatively (paired t test, p = 0.0398). No significant change was observed for the other measurements, as well as for all measurements in the control group (Table 5).

Table 6.

The surgical outcomes among the various groups (12 patients).

| RESULTS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Excellent | Good | Fair | Poor |

| Group A (n = 5) Primary procedures | 60% (3) | 40% (2) | – | – |

| Group B (n = 4) Secondary procedures for TOS recurrence after transaxillary first rib resection elsewhere | 50% (2) | 50% (2) | – | – |

| Group C (n = 3) Procedures for iatrogenic nerve brachial plexus injury during transaxillary 1st rib resection elsewhere | – | 33% (1) | 67% (2) | – |

| Total population (n = 12) | 42% (5) | 42% (5) | 17% (2) | – |

Table 7.

Detailed data in patients (n = 12) who had surgical treatment.

| Number of patients | Group | Sex | Age (years) | Time between injury and surgery (months) | Follow-up | Etiology | Type of lesion | Type of surgery (supraclavicular approach) | Final result [27] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | F | 25 | 9 | 29 | Hypertrophic malunion of the clavicle | C5–T1 | First rib resection and neurolysis | Excellent |

| 2 | A | F | 48 | 23 | 40 | Whiplash injury | C5–T1 | First rib resection and neurolysis | Excellent |

| 3 | B | M | 53 | 18 | 18 | Post-transaxillary first rib resection | C7,C8,T1 | Resection of remnants of first rib and neurolysis | Good |

| 4 | C | M | 32 | 27 | 24 | Post-transaxillary first rib resection | C5–T1 | Resection of remnants of first rib and neurolysis | Good |

| 5 | B | F | 40 | 20 | 148 | Post-transaxillary first rib resection | C5,C6,C7 | Resection of remnants of first rib and neurolysis | Excellent |

| 6 | A | F | 44 | 68 | 16 | Post-radiation mastectomy | C5–T1 | Neurolysis | Good |

| 7 | A | F | 25 | 31 | 21 | Repetitive motion | C5–T1 | First rib resection and neurolysis | Excellent |

| 8 | B | M | 30 | 27 | 56 | Post-transaxillary first rib resection | C5–T1 | Neurolysis | Excellent |

| 9 | C | F | 41 | 14 | 18 | Post-transaxillary first rib resection | C8,T1 | Partial nerve grafting and neurolysis | Fair |

| 10 | A | M | 29 | 50 | 20 | Industrial injury | C5–T1 | First rib resection and neurolysis | Good |

| 11 | C | F | 21 | 6 | 24 | Post-transaxillary first rib resection | C7,C8,T1 | Resection of remnants of first rib and neurolysis | Fair |

| 12 | B | M | 55 | 68 | 20 | Post-transaxillary first rib resection | C5-T1 | Resection of remnants of first rib and neurolysis | Good |

Five patients underwent primary surgery (group A) for TOS. Four of them underwent resection of the first rib through supraclavicular approach and brachial plexus neurolysis (Figs. 1 and 2); the fifth patient underwent microneurolysis of the entire plexus alone. One patient had both supraclavicular and infraclavicular brachial plexus exploration. Another patient had hypertrophic malunion of the previously fractured clavicle which was causing compression. After removal of the first rib and shaving of the clavicle, there was enough release of the neurovascular structures behind the clavicle. All five patients had full relief of symptoms after the surgery. One patient had recurrence of some symptoms 1 year after the surgery; however, this patient had considerable improvement and did not require additional surgery.

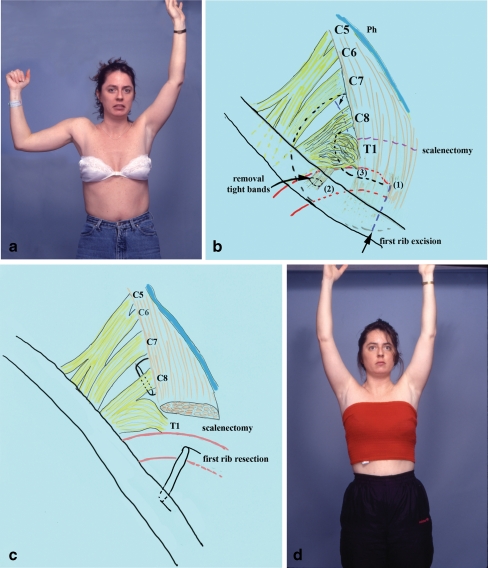

Figure 1.

A 25-year-old female presented with diffuse numbness, intolerable pain, and weakness of the right upper extremity (patient no. 7 in Table 7; a). She had previously undergone carpal tunnel release elsewhere. The time elapsed from onset of symptoms to surgical intervention was 31 months. Provocative clinical tests were positive for neural and vascular compression. She underwent supraclavicular exploration of the right brachial plexus which revealed huge neuroma in continuity at the C8 and T1 roots, compression of the upper and middle trunk, and arterial compression (b). Reconstruction consisted of first rib resection, removal of tight fibrous bands that compressed the thoracic inlet area, anterior scalenectomy, and microneurolysis of the entire supraclavicular plexus (c). At the last follow-up, the patient experienced significant improvement of upper extremity function, complete relief of pain, and she returned to full time work. According to Derkash's classification, she was graded as an excellent result (d).

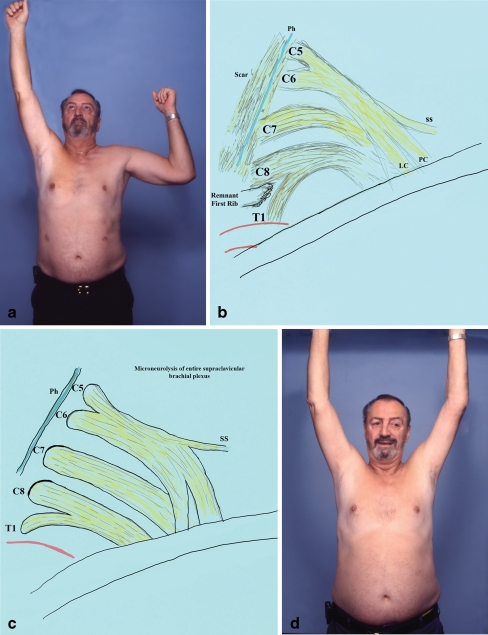

Figure 2.

A 48-year-old female presented with clinical symptoms of left thoracic outlet syndrome. She exhibited weakness of the left upper extremity and severe pain, alleviated only with narcotics (patient no. 2 in Table 7; a). The time elapsed from onset of symptoms to surgical intervention was 23 months. Provocative tests were positive for neural and vascular compression. She underwent supraclavicular plexus exploration which revealed a large anomalous first rib that compressed mostly the lower plexus and the subclavian artery (b). Reconstruction consisted of first rib resection, anterior and middle scalenectomy, and microneurolysis of the entire plexus (c). Nine months later, the patient experienced full motor recovery; she was pain-free, and she returned to preoperative professional and leisure daily activities (excellent result; d).

Four patients with recurrent TOS (group B) underwent secondary surgery after transaxillary first rib resection performed elsewhere. In all cases, exploration of the brachial plexus was done through a supraclavicular approach, and extensive microneurolysis of the brachial plexus was carried out. In three of these surgeries, additional resection of the long posterior stump of the first rib was performed. In the same three patients, remnants of the scalenus anterior muscle had reattached to scar tissue above the pleura compressing once more the brachial plexus; this muscle was totally removed with preservation of the phrenic nerve which usually was involved in the surrounding scar. Two of the four patients had excellent result with complete pain relief, and the remaining two had substantial improvement (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

A 55-year-old male underwent left transaxillary partial first rib resection and anterior scalenectomy elsewhere (patient no. 12 in Table 7). He presented 5.7 years after the surgery with weakness of the left upper extremity (a) and pain which was aggravated during manual work. Exploration revealed severe scarring in the supraclavicular area and hardness in palpation of the entire plexus. Most severe fibrosis was observed in the C8, T1 roots, and lower trunk (b). Reconstruction included extensive neurolysis of the entire brachial plexus, removal of fibrotic bands, anterior and middle scalenectomy, and resection of remnants of the 1st rib (c). At the last office visit, the patient experienced improvement of upper extremity function and intermittent pain which was well tolerated (good result; d).

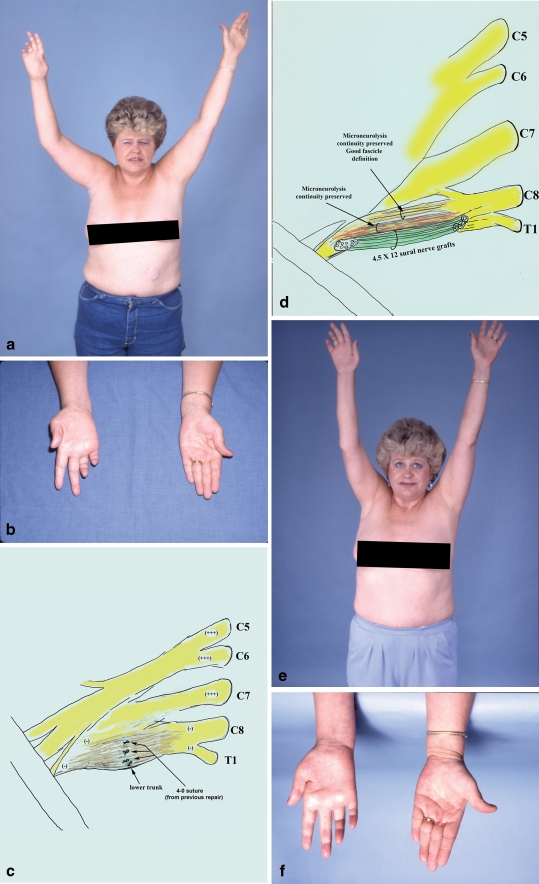

Finally, three patients presented with brachial plexus injury as a complication of previously transaxillary first rib resection (group C). Two of these patients had lower trunk injury. In one case, lower trunk injury was recognized during the first surgery, and it was repaired through the same approach (transaxillary) with 4-0 sutures (!). There were no signs of nerve regeneration, and the patient was referred to our center with severe pain. She underwent exploration of the supraclavicular and infraclavicular brachial plexus, and the lower trunk was repaired with a combination of partial nerve grafting and microneurolysis (Fig. 4). At the final follow-up, she was free of pain, but minimal functional improvement was observed. The other two patients presented with severe hand weakness that developed immediately after the transaxillary first rib resection. Reconstruction with supraclavicular approach included extensive neurolysis of the entire brachial plexus, removal of fibrotic bands, scalenectomy, and resection of remnants of the first rib. Both patients were clinically and electrophysiologically examined 2 years after their surgery in our center and were found to be pain-free. Furthermore, they had improvement with hand function and sensation.

Figure 4.

A 41-year-old female sustained iatrogenic injury to the right brachial plexus during transaxillary first rib resection, elsewhere (patient no. 9 in Table 7). Although there was an attempt to repair the injured lower trunk intraoperatively with 4-0 sutures, there were no signs of nerve regeneration. She developed reflex sympathetic dystrophy which required sympathectomy resulting in mild improvement. This patient was referred to our center and presented 14 months after the initial surgery, with severe burning pain in the ulnar side of the hand and the medial surface of the upper third of the arm, as well as near complete ulnar nerve palsy (a, b). Exploration of the right supraclavicular plexus revealed a large neuroma in the lower trunk. Suture remnants were observed among the scar tissue (c). The lower trunk of the brachial plexus was reconstructed with a combination of partial nerve grafting and extensive microneurolysis (d). Fascicles with perineurial integrity were preserved while those that were replaced by scar were resected, and the gap repaired with 12 sural nerve grafts, each 4.5 cm in length. This patient also had crushing of the intercostobrachial nerves during the transaxillary first rib resection. This lesion required microneurolysis, resection of the neuroma, and nerve repair. At the last office visit (18 months after surgery), she was pain-free over the ulnar nerve distribution, and also over her medial arm, and quite happy with the result (e). However, minimal motor improvement in ulnar innervated targets was observed; she was graded as a fair result (f).

Discussion

The thoracic outlet includes three compartments (the interscalene triangle, costoclavicular space, and retropectoralis minor space), which extend from the cervical spine and mediastinum to the lower border of the pectoralis minor muscle [35]. Dynamically induced compression of the neural, arterial, or venous structures crossing these compartments leads to thoracic outlet syndrome [5, 6, 10, 17, 20, 21, 35]. Patients with bony abnormalities such as cervical rib, first rib exostosis or malunion of the clavicle, and fibromuscular bands, and patients with vascular compression are accepted as true cases of TOS. The remaining large group of cases has no radiologic or electrophysiological demonstration of nerve irritation [17, 20, 35]. However, in our series, about two thirds of the patients presented with neurologic symptoms (weakness was found in 88% of the cases, and decrease of sensation was revealed in 68% of cases) and positive electrophysiological signs (65% of the cases). This large percentage rate could be explained as most of the patients were recurrent and/or complex cases which were referred to an experienced brachial plexus center for second-opinion evaluation and treatment.

Certain postures and positions of the upper extremity, head, and spine can create a direct pressure on the brachial plexus at the various narrow sites of the thoracic outlet [15]. Patients who develop TOS usually are middle age and they have led an active life without symptoms until certain job activities or trauma induced upper extremity pain, numbness, or weakness. In the current series, in both surgical and nonsurgical groups, half of the patients (50%) had a manual job before the onset of symptoms. The patients may report onset following whiplash injury of the cervical spine [19] or secondary to malunion of a fractured clavicle [12]. Previous trauma was reported in 13 (38%) of our cases.

Initially, most patients, except those with vascular problems, are treated non-operatively with physical therapy [17, 20, 35]. Although 50% of our patients who were treated non-operatively were lost to follow-up, the six among the remaining 11 patients had some benefit from a carefully supervised physical therapy program. This consisted of pectoralis stretching, strengthening the muscles between the shoulder blades, good posture, and active neck exercises, including chin tuck, flexion, rotation, lateral bending, and circumduction.

Currently, the most frequently used method for decompression of the thoracic outlet (inlet) is transaxillary first rib resection [4, 7, 13, 20–22, 26–28]. However, different publications suggest that this method alone results in a recurrence rate of approximately 20–30% in experienced hands [3, 32, 33]. Complications of this technique include superficial and deep infection, pneumothorax, vascular injuries, lymphatic duct injury, and neural injuries. The latter usually consists of injury to the lower trunk of the brachial plexus and injury of the long thoracic and/or phrenic nerve [21]. The problem with the transaxillary approach relates to the deep exposure, which makes a comprehensive release of the brachial plexus, especially upper and middle trunk and their divisions, hazardous or impossible. Removal of the posterior portion of the first rib may also be incomplete with the transaxillary approach [32]. In our study, this was confirmed by the high representation of transaxillary first rib resection and the resultant iatrogenic neural injuries in the group of patients who underwent reoperation (seven of the 12 patients). Long posterior stump of the previously resected first rib, overlooked fibromuscular bands, and reattachment of anterior and middle scalene muscles to scar tissue above the pleura were found as possible reasons for early TOS recurrence in these patients.

Supraclavicular approach for thoracic outlet decompression is less popular than the transaxillary approach, but has been advocated by several authors [2, 8, 14, 24, 29]. Maxey et al. [24] reported on 67 patients (72 cases) who underwent decompression through a supraclavicular approach for primary thoracic outlet syndrome. Forty-six (63.9%) of 72 operations resulted in complete resolution of symptoms; 17 (23.6%) cases had partial resolution, and nine (12.5%) patients had no resolution. Morbidity was minimal with six (8.3%) complications. These authors concluded the exposure provided by this technique was safe and superior to that of other approaches.

Moreover, the supraclavicular approach appears to be an effective technique for recurrent thoracic outlet syndrome. Ambrad-Chalela et al. [3], using a supraclavicular approach for recurrent cases of TOS, reported on 20 cases that all (100%) had “excellent” or “good” results from repeat surgery to eliminate the underlying problems (removal of intact or residual rib, pectoralis minor tenotomy, brachial plexus neurolysis, or a combination of these). No complications were observed, and all patients were able to return to activities of daily living.

In our experience, supraclavicular approach provides better exposure of the middle and upper trunks of the brachial plexus. It also enables easier removal of the neck of the first rib with good observation of the surrounding neurovascular structures; thus, injuries of C8 and T1 roots, lower trunk, and long thoracic nerve are less likely to occur. Intercostobrachial cutaneous nerve injury is avoided. The supraclavicular incision also allows performance of complete anterior and middle scalenectomy and excision of potential scalene minimus muscle. Any abnormal anatomical structures that compress the brachial plexus may also be removed. In our series, all nine (100%) patients who underwent primary surgery (n = 5) and secondary surgery for recurrent TOS (n = 4) demonstrated excellent or good results. On the other hand, six (54%) among the 11 patients from the control group had some benefit from the non-operative treatment. With the available categorical and numerical data, the patients from the surgically treated group achieved better results than those of the control group. However, the authors should acknowledge the small size of the samples and the heterogeneity among the various subgroups.

Finally, three patients with iatrogenic brachial plexus injuries after transaxillary first rib resection presented with severe pain and motor and sensory deficits. Reoperation resulted in good result in one case and in fair results in two patients; however, all patients became pain-free. No complications were encountered.

Conclusion

Supraclavicular exploration of the brachial plexus enables precise evaluation of the thoracic inlet and safe identification and release of all abnormal anatomical structures. This approach makes possible the accurate diagnosis and removal of all these anomalies including complete first rib resection with minimal risk to neurovascular structures during primary or secondary surgery. Additionally, this approach allows for excellent visualization of the entire brachial plexus, palpation of every structure, extensive microneurolysis under the operating microscope, and for the appropriate nerve reconstruction in cases of iatrogenic brachial plexus injury after prior transaxillary first rib resection.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supraclavicular Approach for Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. The patient is placed in the supine position. Through a curved supraclavicular incision, the supraclavicular brachial plexus is explored. First, the C5 and C6 roots and upper trunk are identified, the phrenic nerve that is formed by contributions of the C4 and C5 roots, then the C7 root and middle trunk, and finally, the C8 and T1 roots. Microstimulation of the supraclavicular plexus takes place. Note that stimulation of the phrenic nerve results in contraction of the diaphragm. Stimulation of the lateral cord gives rise to contraction of the biceps muscle. However, stimulation of the C8 and T1 roots and the lower trunk does not yield any observable contractions in the hand. The subclavian artery is visualized and protected. Subsequently, resection of the anterior scalene muscle follows. The first rib is carefully exposed, and the periosteum and muscle tissue is elevated off the rib while the pleura is retracted inferiorly with a blunt retractor. Using Kerrison punches, the first rib is transected anteriorly and posteriorly, and removal of an approximately 8–10-cm segment of the first rib takes place. Then, the operating microscope is moved into the operative field, and under high magnification, microneurolysis takes place of the supraclavicular plexus. Bulging of the intraneural contents upon release of the epineurium spells a good prognosis for the patient. The process of microneurolysis is assisted by palpation of the plexus components so that every constituent of the plexus that feels hard to palpation is released. When the entire supraclavicular plexus has been microneurolysed and each component feels soft to palpation, especially C8, T1, and lower trunk, the procedure is completed. (MPG 77468 kb)

Acknowledgments

Disclaimer None of the authors received financial support for this study.

Contributor Information

Julia K. Terzis, Email: mrc@jkterzis.com

Zinon T. Kokkalis, Email: zinon.kokkalis@hotmail.com

References

- 1.Adson AW. Symptoms, differential diagnosis or section of the insertion of the scalenus anticus muscle. J Int Coll Surg. 1951;16:546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altobelli GG, Kudo T, Haas BT, Chandra FA, Moy JL, Ahn SS. Thoracic outlet syndrome: pattern of clinical success after operative decompression. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42(1):122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambrad-Chalela E, Thomas GI, Johansen KH. Recurrent neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. Am J Surg. 2004;187(4):505–510. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barkhordarian S. First rib resection in thoracic outlet syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32(4):565–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colli BO, Carlotti CG, Jr, Assirati JA, Jr, Marques W., Jr Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndromes: a comparison of true and nonspecific syndromes after surgical treatment. Surg Neurol. 2006;65(3):262–271. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooke RA. Thoracic outlet syndrome—aspects of diagnosis in the differential diagnosis of hand–arm vibration syndrome. Occup Med (Lond) 2003;53(5):331–336. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqg097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Degeorges R, Reynaud C, Becquemin JP. Thoracic outlet syndrome surgery: long-term functional results. Ann Vasc Surg. 2004;18(5):558–565. doi: 10.1007/s10016-004-0078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dellon AL. The results of supraclavicular brachial plexus neurolysis (without first rib resection) in management of post-traumatic “thoracic outlet syndrome”. J Reconstr Microsurg. 1993;9(1):11–17. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1006633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demirbag D, Unlu E, Ozdemir F, Genchellac H, Temizoz O, Ozdemir H, et al. The relationship between magnetic resonance imaging findings and postural maneuver and physical examination tests in patients with thoracic outlet syndrome: results of a double-blind, controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(7):844–851. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demondion X, Herbinet P, Sint Jan S, Boutry N, Chantelot C, Cotten A. Imaging assessment of thoracic outlet syndrome. Radiographics. 2006;26(6):1735–1750. doi: 10.1148/rg.266055079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donaghy M, Matkovic Z, Morris P. Surgery for suspected neurogenic thoracic outlet syndromes: a follow up study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:602–606. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.5.602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujita K, Matsuda K, Sakai Y, Sakai H, Mizuno K. Late thoracic outlet syndrome secondary to malunion of the fractured clavicle: case report and review of the literature. J Trauma. 2001;50(2):332–335. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200102000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han S, Yildirim E, Dural K, Ozisik K, Yazkan R, Sakinci U. Transaxillary approach in thoracic outlet syndrome: the importance of resection of the first-rib. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;24(3):428–433. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(03)00333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hempel GK, Shutze WP, Anderson JF, Bukhari HI. 770 consecutive supraclavicular first rib resections for thoracic outlet syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg. 1996;10(5):456–463. doi: 10.1007/BF02000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgs PE, Mackinnon SE. Repetitive motion injuries. Annu Rev Med. 1995;46:1–16. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.46.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howard M, Lee C, Dellon AL. Documentation of brachial plexus compression (in the thoracic inlet) utilizing provocative neurosensory and muscular testing. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2003;19(5):303–312. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang JH, Zager EL. Thoracic outlet syndrome. Neurosurgery. 2004;55(4):897–902. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000137333.04342.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jordan SE, Ahn SS, Gelabert HA. Differentiation of thoracic outlet syndrome from treatment-resistant cervical brachial pain syndromes: development and utilization of a questionnaire, clinical examination and ultrasound evaluation. Pain Physician. 2007;10:441–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kai Y, Oyama M, Kurose S, Inadome T, Oketani Y, Masuda Y. Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome in whiplash injury. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14(6):487–493. doi: 10.1097/00002517-200112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leffert RD. Thoracic outlet syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1994;2(6):317–325. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199411000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leffert RD. The conundrum of thoracic outlet surgery. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;3(4):262–270. doi: 10.1097/00132589-200212000-00005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leffert RD, Perlmutter GS. Thoracic outlet syndrome. Results of 282 transaxillary first rib resections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;368:66–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levin LS, Dellon AL. Pathology of the shoulder as it relates to the differential diagnosis of thoracic outlet compression. J Reconstr Microsurg. 1992;8(4):313–317. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1006714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maxey TS, Reece TB, Ellman PI, Tribble CG, Harthun N, Kron IL, et al. Safety and efficacy of the supraclavicular approach to thoracic outlet decompression. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76(2):396–399. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)00531-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novak CB, Mackinnon SE. Multilevel nerve compression and muscle imbalance in work-related neuromuscular disorders. Am J Ind Med. 2002;41(5):343–352. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roos DB. Transaxillary approach for first rib resection to relieve thoracic outlet syndrome. Ann Surg. 1966;163:354–358. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196603000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roos DB. Experience with first rib resection for thoracic outlet syndrome. Ann Surg. 1971;173(3):429–442. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197103000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samarasam I, Sadhu D, Agarwal S, Nayak S. Surgical management of thoracic outlet syndrome: a 10-year experience. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74(6):450–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2004.03016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheth RN, Campbell JN. Surgical treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome: a randomized trial comparing two operations. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3(5):355–363. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.3.5.0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tender GC, Thomas AJ, Thomas N, Kline DG. Gilliatt-Sumner hand revisited: a 25-year experience. Neurosurgery. 2004;55(4):883–890. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000137889.51323.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terzis JK, Vekris MD, Soucacos P. Outcomes of brachial plexus reconstruction in 204 patients with devastating paralysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(5):1221–1240. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199910000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urschel HC, Kourlis H. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a 50-year experience at Baylor University Medical Center. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2007;20(2):125–135. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2007.11928267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urschel HC, Jr, Razzuk MA. Neurovascular compression in the thoracic outlet: changing management over 50 years. Ann Surg. 1998;228(4):609–617. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199810000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanti C, Natalini L, Romeo A, Tosarelli D, Pillastrini P. Conservative treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome. A review of the literature. Eura Medicophys. 2007;43(1):55–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilbourn AJ. Thoracic outlet syndromes. Neurol Clin. 1999;17(3):477–497. doi: 10.1016/S0733-8619(05)70149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilbourn AJ, Gilliatt RW. Double-crush syndrome: a critical analysis. Neurology. 1997;49(1):21–29. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wood VE, Ellison DW. Results of upper plexus thoracic outlet syndrome operation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58(2):458–461. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)92228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supraclavicular Approach for Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. The patient is placed in the supine position. Through a curved supraclavicular incision, the supraclavicular brachial plexus is explored. First, the C5 and C6 roots and upper trunk are identified, the phrenic nerve that is formed by contributions of the C4 and C5 roots, then the C7 root and middle trunk, and finally, the C8 and T1 roots. Microstimulation of the supraclavicular plexus takes place. Note that stimulation of the phrenic nerve results in contraction of the diaphragm. Stimulation of the lateral cord gives rise to contraction of the biceps muscle. However, stimulation of the C8 and T1 roots and the lower trunk does not yield any observable contractions in the hand. The subclavian artery is visualized and protected. Subsequently, resection of the anterior scalene muscle follows. The first rib is carefully exposed, and the periosteum and muscle tissue is elevated off the rib while the pleura is retracted inferiorly with a blunt retractor. Using Kerrison punches, the first rib is transected anteriorly and posteriorly, and removal of an approximately 8–10-cm segment of the first rib takes place. Then, the operating microscope is moved into the operative field, and under high magnification, microneurolysis takes place of the supraclavicular plexus. Bulging of the intraneural contents upon release of the epineurium spells a good prognosis for the patient. The process of microneurolysis is assisted by palpation of the plexus components so that every constituent of the plexus that feels hard to palpation is released. When the entire supraclavicular plexus has been microneurolysed and each component feels soft to palpation, especially C8, T1, and lower trunk, the procedure is completed. (MPG 77468 kb)