Abstract

Background

Warfarin is commonly prescribed for prophylaxis and treatment of thromboembolism after orthopedic surgery. During warfarin initiation, out-of-range International Normalized Ratio (INR) values and adverse events are common.

Methods

In orthopedic patients beginning warfarin therapy, we developed and prospectively validated pharmacogenetic and clinical dose refinement algorithms to revise the estimated therapeutic dose after 4 days of therapy.

Results

The pharmacogenetic algorithm used the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C9 genotype, smoking status, perioperative blood loss, liver disease, INR values, and dose history to predict the therapeutic dose. The R2 was 82% in a derivation cohort (N = 86), and 70% when used prospectively (N = 146). The R2 of the clinical algorithm that used INR values and dose history to predict the therapeutic dose was 57% in a derivation cohort (N = 178), and 48% in a prospective validation cohort (N = 146). In one month of prospective follow-up, the percent time spent in the therapeutic range was 7% higher (95% CI: 2.7%–11.7%) in the pharmacogenetic cohort. The risk of laboratory or clinical adverse event was also significantly reduced in the pharmacogenetic cohort (Hazard Ratio 0.54; 95% CI: 0.29–0.97).

Conclusions

Warfarin dose adjustments that incorporate genotype and clinical variables available after four warfarin doses are accurate. In this non-randomized, prospective study, pharmacogenetic dose refinements were associated with more time spent in the therapeutic range and fewer laboratory or clinical adverse events. To facilitate gene-guided warfarin dosing we created a non-profit website, www.WarfarinDosing.org.

Keywords: Warfarin, Pharmacogenetics, Dosing Algorithm, Anticoagulants, Orthopedic Surgery

Introduction

To prevent or treat venous and arterial thromboembolism, an estimated 2 million Americans begin warfarin (Coumadin® and others) each year [1]. Unfortunately, warfarin has a narrow therapeutic index and marked inter-individual variation in dose requirements. Traditional dose titration based on the International Normalized Ratio (INR) response results in a high incidence of adverse events.[2–4]

Recent studies emphasize the importance of certain genetic markers in explaining inter-individual variation in warfarin requirements.[4–6] Common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C9 system (CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3) are associated with impaired metabolism of warfarin,[2, 7–10] leading to a decrease in dose requirements and an increase in the time it takes to become therapeutic. SNPs in the gene for vitamin K epoxide reductase complex 1 (VKORC1) correlate with warfarin sensitivity.[11–14] In recognition of the effects of genetic variation, on August 16, 2007 the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the label change of Coumadin to recommend lower initial doses in patients known to have certain SNPs in CYP2C9 or VKORC1.[15]

Several pharmacogenetic algorithms have been developed to predict the therapeutic warfarin dose at baseline from these SNPs,[12, 16–19] but they explain only half of the variability in warfarin dose (derivation R2 ranging from 47% to 61%). Recently, a single-centered randomized trial of one of these algorithms found no significant improvement in laboratory or clinical adverse events.[20] Another single-centered trial tailored warfarin adjustments as well as the baseline dose according to CYP2C9 genotype. This protocol improved INR control, reduced the delay until the dose was therapeutic, and averted minor bleeds, but did not consider VKORC1 genotype.[21]

Pharmacogenetic dose-refinement algorithms are a complementary approach to estimating the therapeutic dose: they combine genotype and clinical factors with initial INR response after several warfarin doses have already been given.[5] Dose revision algorithms are important because they allow clinicians to adjust the dose around the time of hospital discharge and before the second week of warfarin therapy—the time when supratherapeutic INR values occur commonly.[22] The potential benefit of pharmacogenetic dose-refinement algorithms, however, remains uncertain. Thus, the goals of this study were: (1) to develop a pharmacogenetic dose-refinement algorithm to predict the therapeutic dose after 4 days of therapy (the INR4 dose-refinement algorithm) and (2) prospectively, to compare 30-day laboratory and clinical outcomes for warfarin therapy tailored to clinical vs. pharmacogenetic factors.

Materials and Methods

All patients provided written informed consent in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. The Human Research Protection Offices at Washington University in St. Louis and at Kaiser Permanente in Colorado approved the protocol. 265 patients were recruited who agreed to pharmacogenetic therapy; 412 received clinically-based therapy. Patients were not randomized to study arms.

Pharmacogenetic Cohorts

To derive and validate a pharmacogenetic INR4 refinement algorithm, we studied 265 orthopedic patients who were referred to one of two anticoagulation services: the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Anticoagulation Service at the Washington University Medical Center (WUMC) or the Clinical Pharmacy Anticoagulation Service at Kaiser Permanente in Colorado (KP). The derivation pharmacogenetic cohort consisted of 86 participants from prior studies[5, 9] who had an INR measured after 4 warfarin doses (INR4) and achieved a stable dose in the therapeutic range during follow-up.

The validation pharmacogenetic cohort consisted of 142 WUMC patients and 37 KP patients prospectively followed between January 2007 and February 2008. For generalization, we included patients regardless of drug interactions, comorbidities, or adherence to the study protocol. We excluded patients who did not have an INR4 measured or who had contraindications to warfarin treatment, an age under 18, or a previous therapeutic warfarin dose.

Patients receiving pharmacogenetic care took their first daily dose 18–24 hours before surgery. Their initial three doses were tailored to clinical factors (age, race, body surface area [BSA], amiodarone use, smoking status, and target INR), CYP2C9 genotype,[9] and after February 27, 2006 also to VKORC1 genotype.[19] In all pharmacogenetic cohorts, the dose on day 4 was per published INR3 nomogram[5] implemented on www.WarfarinDosing.org or a similar paper-based prototype. In the validation pharmacogenetic cohort, the dose on day 5 was given per the pharmacogenetic INR4 dose-refinement algorithm developed herein; participants continued on this dose until it was clinically necessary to adjust it (median duration, 5 days). We prescribed warfarin for approximately one month after hospital discharge. In the validation pharmacogenetic cohort, 33 patients (17%) stopped their warfarin prior to becoming therapeutic. Using an intent-to-treat basis in the analysis of clinical outcomes, we included these patients as well as patients whose 5th warfarin dose deviated from that estimated by the pharmacogenetic INR4 dose-refinement algorithm by more than 1 mg (N=20, 14%).

Timing of warfarin administration and INR blood draws was per protocol. Inpatients received warfarin between 14:00 and 17:00. After INR4, patients had INR values collected on Mondays and Thursdays. With each INR, patients were queried about compliance and adverse events. For patients who had estimated blood loss (EBL) during surgery recorded as “minimal” or < 60 ml (N = 3), we rounded EBL to 60 ml.

Clinical Cohorts

To derive and validate the clinical INR4 dose-refinement algorithm we studied patients having the same inclusion and exclusion criteria as in the pharmacogenetic cohorts. The clinical derivation cohort consisted of 178 orthopedic patients whom we followed between August 2003 and November 2006 at WUMC. We prospectively validated the clinical algorithm in an independent cohort of 233 WUMC patients whose warfarin we managed between November 2006 and January 2007.

Timing of warfarin administration and INR blood draws in the two (derivation and validation) clinical cohorts followed the same protocol as in the pharmacogenetic cohorts. Except for 18 individuals who were included from the derivation pharmacogenetic cohort, the initial 3 doses in both the derivation and validation clinical cohorts were based on clinical algorithms.[19] In the derivation clinical cohort, dose refinements were made per local nomogram. In the validation clinical cohort, dose 4 was based on a clinical refinement algorithm [23] and dose 5 was based on the clinical INR4 dose-refinement algorithm developed here. Participants continued on this fifth dose until it was clinically necessary to adjust it based on subsequent INR values (median duration, 5 days). As in the pharmacogenetic cohort, analysis of secondary outcomes was performed on an intent-to-treat basis and included clinically-dosed patients whose 5th warfarin dose deviated from the estimated therapeutic dose by more than 1 mg (N=51, 35%) as well as patients who stopped their warfarin therapy prior to achieving a therapeutic dose (N=87, 37%).

Genotyping

For the pharmacogenetic cohorts we collected 10 ml of anticoagulated whole blood and, for WUMC participants enrolled after November 2006, a saliva sample. We isolated genomic DNA from these samples using Puregene® DNA purification reagents and protocol (Gentra, Minneapolis MN). Each sample was genotyped for the CYP2C9*2 [rs1799853] and CYP2C9*3 [rs1057910] alleles as well as the VKORC1 SNP −1639/3673 G>A [rs9923231]. Samples collected from August 2003 through July 2006 (N=86) were genotyped using previously described methods.[5] WUMC samples collected after that date (N=142) were genotyped using one of two commercial platforms: (1) Invader® assay (Third Wave Technologies, Madison WI) with the TECAN GENios FL™ fluorescence plate reader (Zurich, Switzerland), and/or (2) INFINITI™ analyzer (Autogenomics, Carlsbad, CA). We selected these platforms because they facilitate same-day genotyping and were 99%–100% accurate [24]. KP samples were genotyped using the Invader® assay. We performed and interpreted all genotyping while blinded to clinical variables and therapeutic dose.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome was the accuracy of the algorithms, measured by R2. Consistent with our prior work,[5] a therapeutic dose was defined as the warfarin dose that yielded an INR in the therapeutic range following at least 6 consecutive days of the same dose for the derivation cohorts. For the validation cohorts, we required at least 7 days of the same dose and at least 2 therapeutic INR values. The target INR was 2.2 for most patients (2.0 for KP patients), and a therapeutic INR was defined as the target +/− 0.5 inclusive (e.g. 1.7 to 2.7). The composite secondary endpoint was an INR > (target INR + 1.5) or clinical adverse event (a major hemorrhage or symptomatic venous thromboembolism). Major hemorrhage was defined as any bleed that required medical attention. We calculated the percent of time below, in, and above the therapeutic range on days 4–30 of therapy using linear interpolation for missing INR values.[25]

Statistical Analysis

In both derivation cohorts and later in the pooled cohorts, we analyzed demographic, clinical, and pharmacological information for relationships with warfarin dose (Table 1). We used dummy variables to code for the demographic factors, clinical variables, smoking status, and medications. ‘Liver disease’ was defined as hepatic cirrhosis, a two-fold elevation of any liver transaminase, or an albumin < 3.6. ‘Statin’ was any HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor except pravastatin, which does not interact with warfarin.[26] In the pharmacogenetic cohorts we coded CYP2C9 *2 and *3 SNPs as 0 (if absent), 1 (heterozygous), or 2 (homozygous) to model additive allelic effects on warfarin dose. Similarly, we coded VKORC1−1639/3673 G>A as 0 (if absent), 1 (heterozygous), or 2 (homozygous AA). We used the natural logarithm (ln) to transform the skewed distributions of therapeutic dose, EBL, and post-operative INR values. Using stepwise and backward regression we offered non-collinear variables and biologically plausible interaction terms to the regression models and retained variables that were statistically significant (two-tailed P ≤ 0.05). When we excluded KP patients from a secondary analysis, p-values were not qualitatively affected, justifying the pooling of data from KP and WUMC.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical information in the derivation and validation cohorts.

| Derivation Cohorts | Validation Cohorts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Cohort (N=86) |

Clinical Cohort (N=178) |

Genetic Cohort (N=179) |

Clinical Cohort (N=233) |

|

| Demographic Variables | ||||

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 60 (14) | 59 (15) | 57 (12) | 59 (15) |

| BSA, mean (SD), m2 | 2.0 (0.28) | 2.0 (0.28) | 2.0 (0.25) | 2.0 (0.27) |

| Male, N (%) | 42 (49) | 88 (49) | 86 (48) | 109 (47) |

| African-American, N (%) | 11 (13) | 24 (13) | 17 (9) | 27 (12) |

| Caucasian, N (%) | 74 (86) | 153 (86) | 160 (89) | 203 (87) |

| Other Race, N (%) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Orthopedic Indication | ||||

| Total Hip Replacement, N (%) | 84 (98) | 172 (97) | 158 (88) | 213 (91) |

| Total Knee Replacement, N (%) | 2 (2) | 6 (3) | 21 (12) | 20 (9) |

| Genotypes | ||||

| CYP2C9*2 Allele Frequency | 0.14 | n.a. | 0.12 | n.a. |

| CYP2C9*3 Allele Frequency | 0.07 | n.a. | 0.06 | n.a. |

| VKORC1 A Allele Frequency | 0.31 | n.a. | 0.36 | n.a. |

| Clinical Variables | ||||

| Therapeutic Warfarin Dose, geometric mean (SD), mg |

5.1 (2.5) | 4.6 (2.2) | 4.8 (2.3) | 4.4 (2.1) |

| Estimated Blood Loss, geometric mean (SD), mL |

400 (597) | 442 (749) | 332 (325) | 357 (480) |

| INR2, geometric mean (SD) | 1.3 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.2) |

| INR3, geometric mean (SD) | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.4) |

| INR4, geometric mean (SD) | 1.7 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.3) | 1.7 (0.5) |

| Target INR, mean (SD) | 2.3 (0.2) | 2.2 (0.1) | 2.2(0.1) | 2.2 (0.1) |

| 1st Dose, mean (SD), mg* | 6.9 (2.3) | 5.4 (1.7) | 5.3 (1.4) | 4.8 (1.1) |

| 2nd Dose, mean (SD), mg | 4.7 (1.8) | 4.8 (1.4) | 4.9 (1.6) | 4.7 (1.4) |

| 3rd Dose, mean (SD), mg | 5 (2.3) | 4.8 (1.5) | 4.8 (1.8) | 4.6 (1.5) |

| Statin Use, N (%) | 13 (15) | 26 (15) | 47 (26) | 63 (27) |

| Amiodarone Use, N (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Current Smoker, N (%) | 16 (19) | 23 (13) | 25 (14) | 39 (17) |

| Liver Disease, N (%) | 2 (2) | 4 (2) | 3 (2) | 10 (4) |

SD=Standard Deviation. BSA=body surface area. INR=International Normalized Ratio. Statin = any HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor except for pravastatin.

N.A. means not available.

P < 0.05 between the validation cohorts.

We validated the INR4 refinement algorithms in independent cohorts. We calculated absolute prediction error as |predicted dose – therapeutic dose|, where | · | is the absolute value operator. We calculated relative error as |predicted dose – therapeutic dose|/ therapeutic dose. We tested the difference in R2 between clinical and pharmacogenetic cohorts using bootstrap re-sampling with 1000 samples. We used the Cox proportional hazard model to test the composite endpoint. We performed statistical calculations in SAS (Version 9.1for Windows; SAS Institute, Inc; Cary, NC).

To derive a pooled pharmacogenetic algorithm, we used therapeutic participants from both pharmacogenetic cohorts (N=232). We derived the pooled clinical cohort from all participants but included those who were in both pharmacogenetic and clinical cohorts (N = 25) only once. Because of collinearity of doses 1–3, we offered their average into the regression model.

Results

Derivation

Demographic and clinical variables were similarly distributed among the cohorts (Table 1). In the derivation pharmacogenetic cohort, therapeutic dose was inversely correlated with INR4 response, CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3 alleles (P<0.001, P=0.007, and P<0.001, respectively). Other significant predictors of therapeutic dose were the first three warfarin doses, smoking status, liver disease, and EBL. In contrast, VKORC1−1639/3673 G>A (rs9923231), was not a significant independent predictor of dose nor was sex or race. This algorithm explained 82% of the variation in the derivation pharmacogenetic cohort:

Therapeutic Dose (mg/day) = EXP[1.403 + 0.082 × 1st Warfarin Dose + 0.037 × 2nd Warfarin Dose + 0.037 × 3rd Warfarin Dose −0.130 × CYP2C9*2 + 0.199 × Smokes −1.989 × ln(INR4) + 0.140 × ln(EBL) × ln(INR4) −0.385 × CYP2C9*3 −0.463 × Liver Disease], where EXP is the exponential operator, Smokes indicates smoking status, and ln() is the natural logarithm operator.

The clinical algorithm that best estimated therapeutic warfarin dose included the first three warfarin doses and INR response after 4 days of warfarin therapy. Again, INR4 correlated inversely with therapeutic dose (P<0.001). Statin use, smoking, and history of liver disease were offered to the clinical algorithm, but were not significant predictors (P=0.11, P=0.25, and P=0.62, respectively). The clinical INR4 algorithm explained 57% of the therapeutic dose variation in the WUMC clinical derivation cohort:

Therapeutic Dose (mg/day) = EXP[1.254 + 0.071 × 1st Warfarin Dose + 0.053 × 2nd Warfarin dose + 0.053 × 3rd Warfarin dose −1.159 × ln(INR4)].

Validation

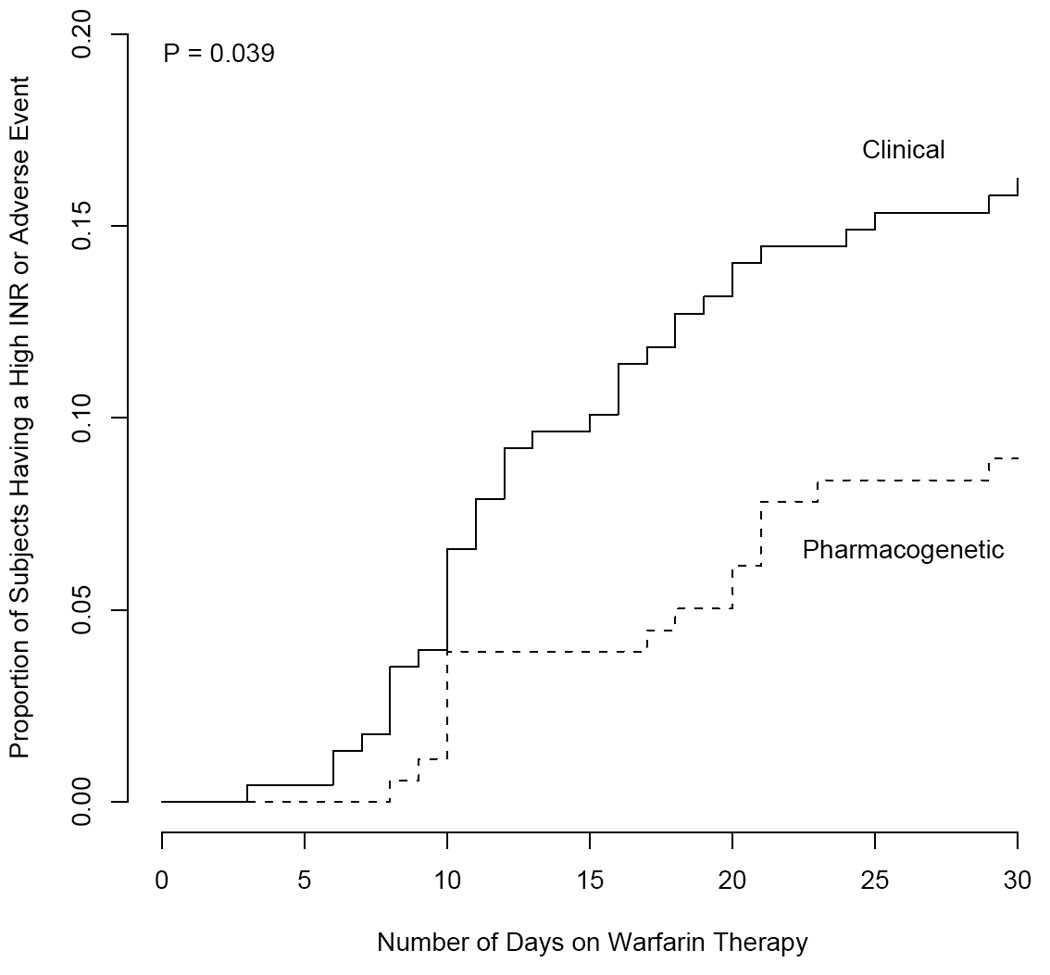

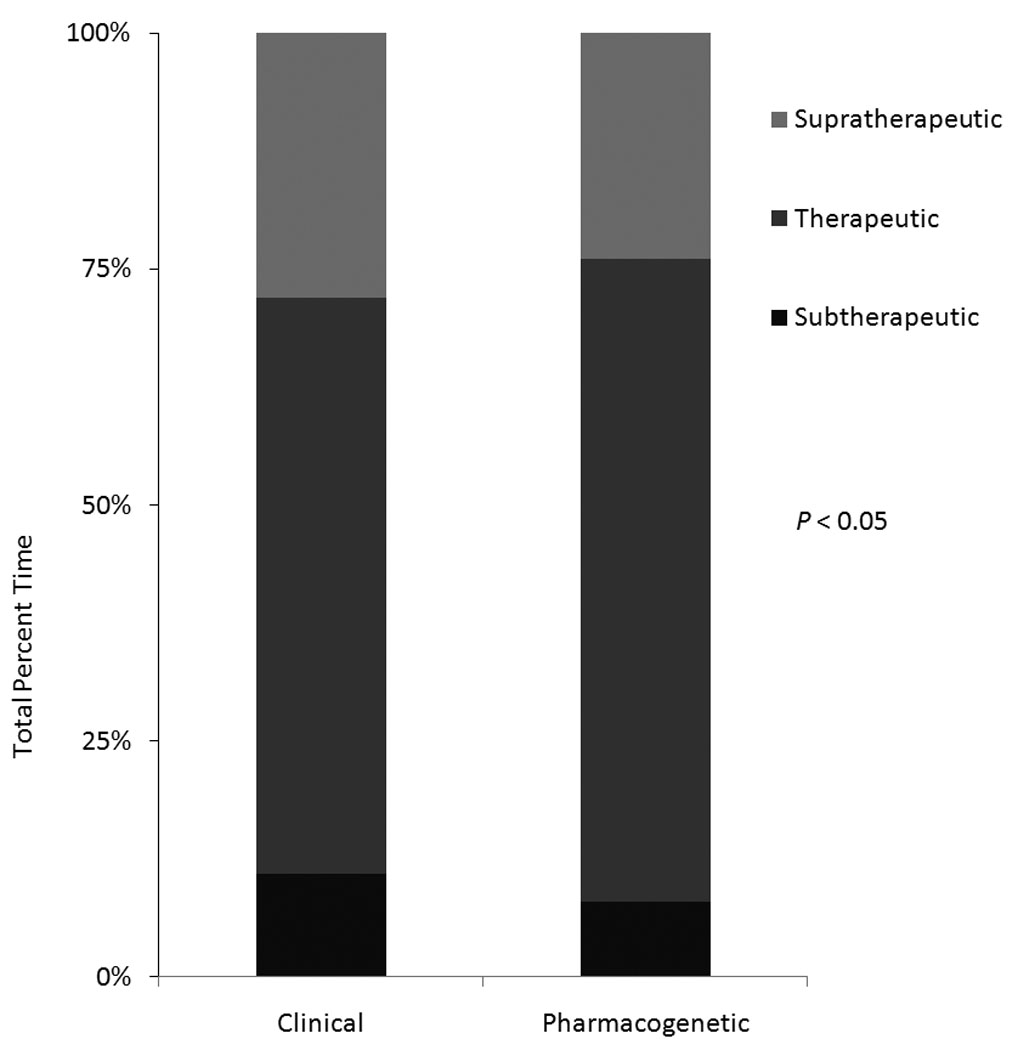

In the validation pharmacogenetic cohort, the pharmacogenetic algorithm explained 70% of the dose variation (R2=70%), which was significantly greater (P=0.009) than the 48% R2 in the validation clinical cohort (95% CI on difference= 3.3% to 33.6%) (Table 2). Among the validation cohorts, the hazard ratio for the composite endpoint in the pharmacogenetic vs. clinical cohorts was 0.54 (95% CI: 0.29 to 0.97) (P < 0.039, Figure 1). The odds of having a clinical adverse event (not including laboratory events) in the two validation cohorts were not significantly different (Table 3). The pharmacogenetic validation cohort spent 7% more time in the therapeutic range (P=0.002; 95% CI: 2.7%, 11.7%): 3% less time supratherapeutic (P=0.038; 0.0% to 5.6%), and 4% less time subtherapeutic (P=0.045; 0.1% to 8.7%) (Figure 2, Table 3). Median length of follow-up was similar in the two validation cohorts.

Table 2.

Accuracy of INR4 dose refinement algorithms in the validation cohorts.

| R2 | MAE (mg/day) [25%,75%] |

Predictions within 1 mg of therapeutic dose |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Algorithm (N=146) |

48% | 0.74 [0.29,1.4] | 70% |

| Pharmacogenetic Algorithm (N=146) |

70% | 0.73 [0.31,1.29] | 73% |

MAE=Median Absolute Error. INR4 = International Normalized Ratio after the fourth warfarin dose.

Figure 1.

Time until a laboratory or clinical adverse event in the validation cohorts.

Table 3.

Thirty-day outcomes of clinical and pharmacogenetic algorithms in the validation cohorts.

| Clinical (N=233) | Genetic (N=179) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean PTTR (SD)* | 61 (23.6) | 68 (22.3) |

| Mean % time supratherapeutic (SD)* | 11 (16) | 8 (11.4) |

| Mean % time subtherapeutic (SD)* | 28 (22.5) | 24 (21.3) |

| Symptomatic adverse events (%) | 7 (3.0) | 1 (0.6) |

| DVT | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| PE | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Bleed | 4 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) |

PTTR=Percent Time in Therapeutic Range. DVT=Deep Vein Thrombosis. PE=Pulmonary Embolism. Bleed=a hemorrhage requiring hospital treatment.

P < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Percent time spent above, in, and below the therapeutic INR range in the clinical and pharmacogenetic validation cohorts.

Pooled Algorithm

After pooling the two pharmacogenetic cohorts (N=232), the most accurate dose revision algorithm was:

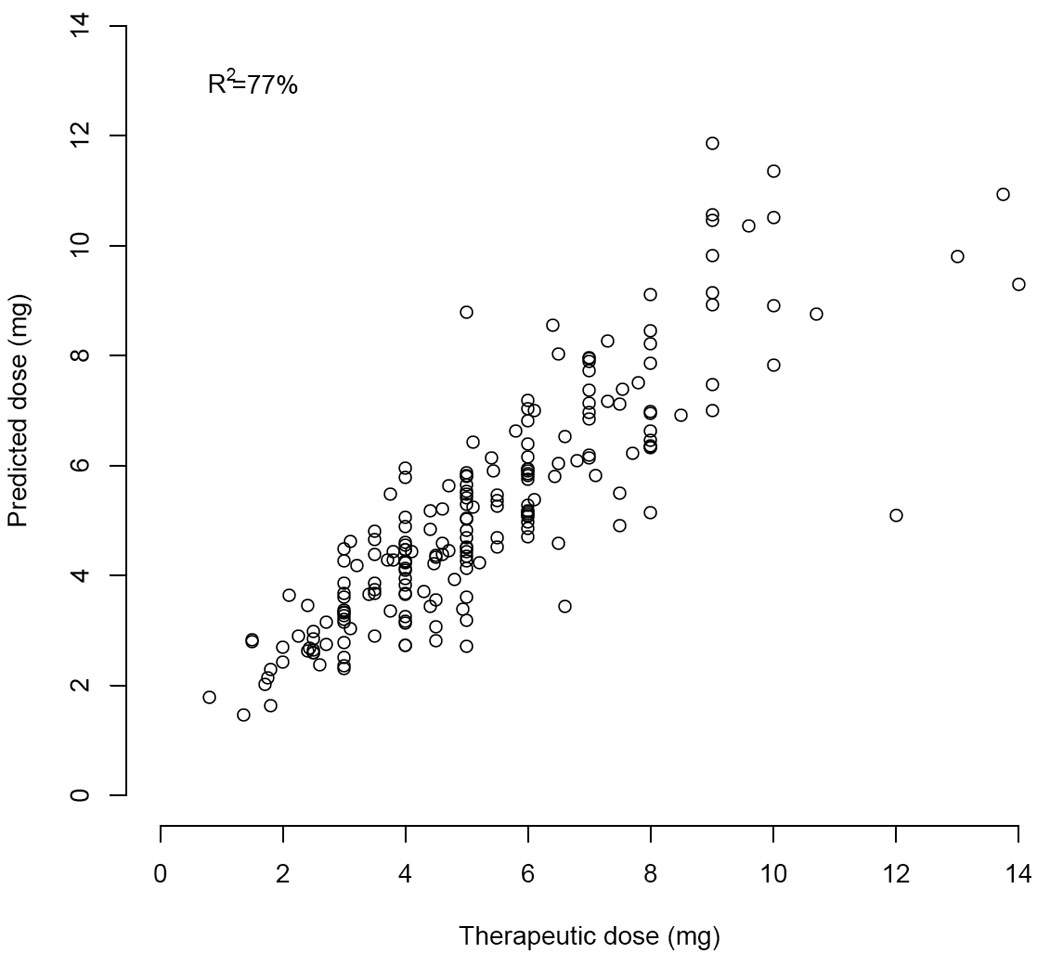

Therapeutic dose = EXP[1.098 + 0.048 × 1st warfarin dose + 0.048 × 2nd warfarin dose + 0.048 × 3rd Warfarin Dose+ 0.055 × ln(EBL) − 0.145 × Statin − 0.100 × VKORC1 − 0.102 × CYP2C9*2 − 0.315 × CYP2C9*3 + 0.128 × Smokes − 0.888 × ln(INR4)], where VKORC1 indicates the number of G>A alleles at rs9923231. This algorithm explained 77% of the variation in the pooled pharmacogenetic cohort (Table 4), resulted in a median absolute dosing error of 0.68 mg/day, and was highly correlated (R2 = 93%) with the pharmacogenetic algorithm that we validated prospectively (Figure 3).

Table 4.

Multivariate Analysis: Independent Predictors of Therapeutic Warfarin Dose using the Pharmacogenetic and Clinical INR4 Algorithms in the pooled cohorts.

| Model Entry |

Variable | % Change in therapeutic warfarin dose (95% CI) |

R2 after entry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacogenetic Model (N=232) | |||

| 1** | Average (1st, 2nd, and 3rd Warfarin Doses) |

+15.5% (12.1% to 18.9%) | 0.54 |

| 2** | ln(INR4) | −19.9% (−23.3% to −16.4%) | 0.68 |

| 3** | CYP2C9*3 | −27% (−33.7% to −19.7%) | 0.71 |

| 4** | Statin | −13.5% (−19.5% to −7%) | 0.73 |

| 5** | Current Smoker | +13.7% (4.1% to 24.2%) | 0.74 |

| 6** | VKORC1 | −9.5% (−14.9% to −3.8%) | 0.75 |

| 7* | CYP2C9*2 | −9.7% (−16.3% to −2.6%) | 0.76 |

| 8* | ln(EBL) | +2.8% (0.7% to 5%) | 0.77 |

| Clinical Model (N=531) | |||

| 1** | Average (2nd and 3rd Warfarin Doses) |

+20.6% (18.3% to 23%) | 0.36 |

| 2** | ln(INR4) | −22.7% (−24.9% to −20.4%) | 0.59 |

| 3** | Statin | −8.5% (−13.8% to −2.8%) | 0.60 |

| 4* | ln(EBL) | +1.8% (0.2% to 3.4%) | 0.60 |

| 5* | Current Smoker | +7.9% (0.6% to 15.7%) | 0.61 |

Percent change was calculated per 1 mg change in warfarin doses, per 0.25 change ln(INR4), per CYP2C9 and VKORC1 allele.

Ln()= the natural logarithm. INR4= International Normalized Ratio after four warfarin doses. Statin = any HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor except for pravastatin. EBL= Estimated Blood Loss.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.005.

Figure 3.

Actual versus predicted doses in the pooled pharmacogenetic cohort.

The clinical algorithm that best explained the variation in the pooled dataset of derivation and validation pharmacogenetic and clinical cohorts (N=531) was:

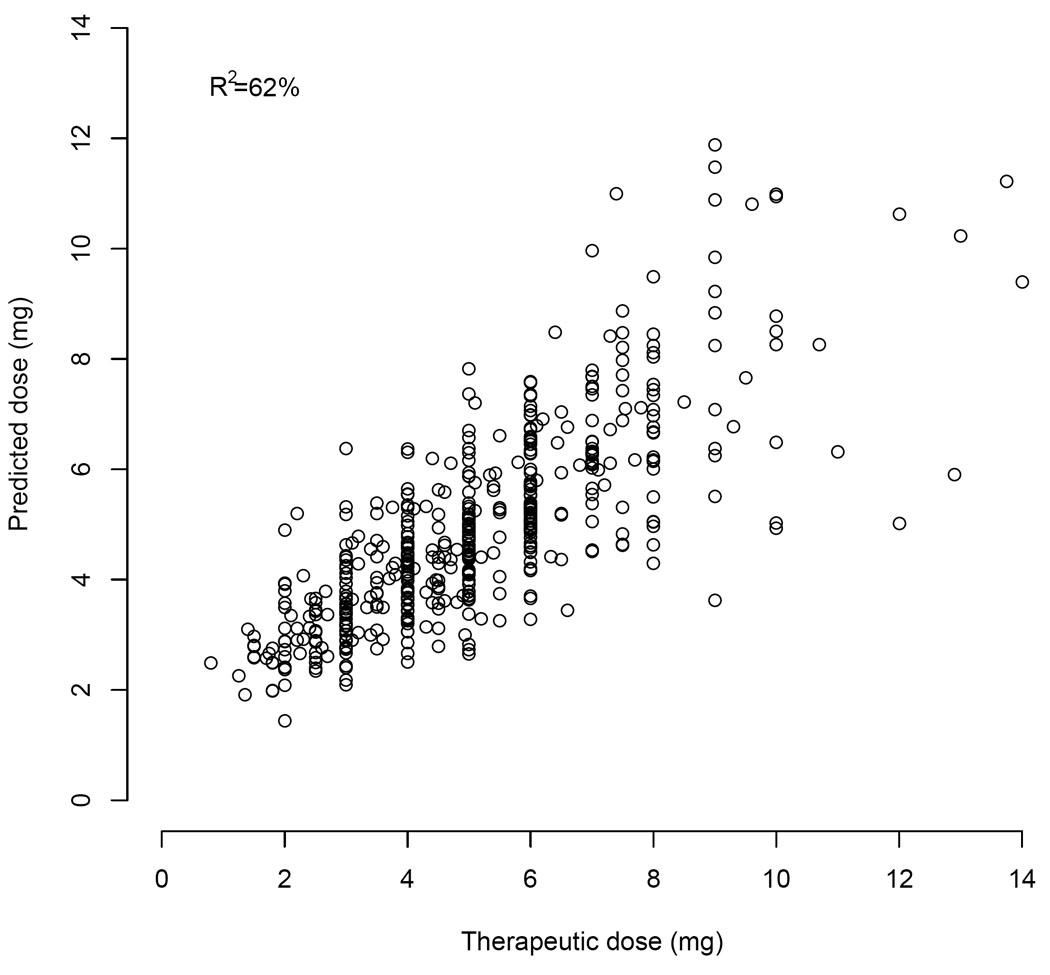

Therapeutic dose = EXP[0.927+ 0.035× ln (EBL) + 0.062 × 1st Warfarin Dose − 0.08830 × Statin + 0.062 × 2nd Warfarin Dose + 0.062 × 3rd Warfarin Dose − 1.029 × ln(INR4) + 0.076 × Smokes]. This algorithm explained 61% of the variation in the pooled clinical cohort (Table 4), had a median absolute error or 0.74 mg/day, and was highly correlated (R2 = 94%) with the clinical algorithm that we validated prospectively (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Actual versus predicted doses in the pooled clinical cohort.

Discussion

Warfarin initiation carries a high risk of adverse events.[4, 27, 28] Traditionally, nomograms attempted to minimize this risk through trial-and-error dose refinements based on an INR value after the third or fourth warfarin dose.[29–32] Although the INR response to warfarin indeed correlated with therapeutic dose, additional factors predicted the therapeutic dose: the initial warfarin doses, CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genotypes, statin use, smoking, EBL, and possibly liver disease. By systematically taking these factors into account as proposed here, clinicians can estimate the therapeutic dose after four days of warfarin therapy more accurately than ever before. Compared to clinical dosing, pharmacogenetic dosing for days 1–5 of warfarin therapy in orthopedic patients was associated with more accurate predictions of the therapeutic warfarin dose, better INR control, and fewer laboratory or clinical adverse events.

Similar to dose-initiation pharmacogenetic algorithms, CYP2C9*2 and *3 alleles were significant predictors of therapeutic dose in the INR4 dose-refinement algorithms developed here.[12, 16–18] Although VKORC1 genotype was the first variable to enter a stepwise regression algorithm that predicted initial dose,[19] it was the sixth variable to enter the pharmacogenetic algorithm developed here (Table 4). In the pooled dataset as well, VKORC1 contributed only 1% to the total R2. These observations suggest that information on warfarin sensitivity can be captured by INR4. These results are similar to a recent cohort study, which found that VKORC1 correlated with INR response during the 1st week of therapy, but its association with dose quickly waned .[22] We hypothesize that the reason CYP2C9 remains highly predictive whereas VKORC1 does not, is due to the mechanism of action: CYP2C9 affects S-warfarin metabolism while VKORC1 affects the sensitivity. Initially, INR response reflects warfarin sensitivity, but not S-warfarin half life.

Just as the predictive ability of VKORC1 appears to wane over time, body size and age were not independent predictors of warfarin dose in any INR4-based algorithm, despite a correlation between these variables and dose in prior work.[7, 12, 16–19] Thus, body size and age may not be important predictors of dose revisions, at least when initial doses are tailored to body size and age, as in this study.

Other variables related to warfarin dose remain important even after being taken into account in earlier prescriptions. The correlation between warfarin dose revision and smoking status in the pharmacogenetic cohorts is consistent with the increase in warfarin clearance from smoking.[33] The association between statin use and therapeutic dose is consistent with assertions that statins (other than pravastatin) reduce cytochrome P450 metabolism.[26, 34] Liver disease was not significant in the final model, but clinicians likely lowered initial doses in such patients, masking any potential effect.

Among validation cohorts, the time until a composite outcome was significantly delayed in the pharmacogenetic cohort (P=0.039). Although most outcomes were supratherapeutic INR values (rather than symptomatic events), there is a strong correlation between such values and major or fatal hemorrhages.[28, 35] While non-randomized studies such as this one cannot prove causality, the improved accuracy of the pharmacogenetic algorithm may help prevent these outcomes. The first pharmacogenetic algorithm validated at 70% (95% CI: 58.4% to 74.8%) and the pooled pharmacogenetic algorithm had a derivation R2 of 77%. Because initial doses in the pharmacogenetic cohort were tailored to genotype, some of the benefit in that cohort is likely due to the accuracy of the day 1–3 pharmacogenetic algorithms.[19] For comparison, pharmacogenetic algorithms used at time of warfarin initiation have an R2 of 47% to 61%.[12, 17, 19, 36] Clinical algorithms used at time of warfarin initiation have an R2 of 17% to 22%[19] and clinical algorithms used after 3 warfarin doses have an R2 of approximately 53%.[23]

Our results are consistent from those of smaller, randomized trials. In the trial by Caraco and colleagues, participants randomized to CYP2C9 testing had few minor hemorrhages and fewer supratherapeutic INR values than participants randomized to clinical dosing.[21] In that study and ours (Table 1), patients prescribed pharmacogenetic therapy averaged higher initial doses than participants treated clinically—which would have decreased the time spent subtherapeutic (Figure 2). In the trial by Anderson and colleagues, participants randomized to pharmacogenetic testing had no reduction in adverse events, but did have more accurate estimations of their therapeutic dose—an observation that we also made (Table 2). A minor difference between the finding in their trials and ours is that we found a significant reduction in supratherapeutic INR values (Figure 2) and the trials did not. Nevertheless, they had similar trends and were not powered to detect a 3% absolute reduction, which is what we found (Table 3).

To limit bias that could have been caused by differential management, both prospective cohorts were managed by anticoagulation services, and the clinical and pharmacogenetic cohorts were closely matched (Table 1). Nevertheless, potential biases remain in any non-randomized study. Another limitation is that we did not evaluate the pharmacogenetic strategy in non-orthopedic patients, Asian patients, or patients who received loading doses (e.g. 10 mg for initial days). A minor limitation is that although R2 is a standard measure of accuracy it can only be measured in participants who achieved stable therapeutic doses.

Despite these limitations, the algorithms developed here have potential to improve the safety and efficiency of warfarin initiation, especially in orthopedic patients where all warfarin doses can be tailored to genotype, without delaying warfarin initiation. We have made the pharmacogenetic and clinical algorithms available at a non-profit website, www.WarfarinDosing.org, and propose that they be investigated in a randomized trial.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research has been provided by the National Institute of Health (R01 HL074724) and the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial interest in the conclusions of this study and have deposited de-identified data used for the pharmacogenetic cohorts at PharmGKB, accession #PS206604, #PS206605, #PS206606, #PS206608, #PS206799, and others pending.

Addendum

Petra Lenzini analyzed data and drafted the manuscript. Gloria Grice, Paul Milligan, and Mary Beth Dowd recruited and managed patients and drafted the manuscript. Sumeet Subherwal wrote the protocol and edited the manuscript. Elena Deych drafted the manuscript and curated data. Charles S. Eby oversaw genotyping process and edited the manuscript. Cristi King and Rhonda Porche-Sorbet genotyped WUMC participants and edited the manuscript. Eric Millican, Renee Marchand, and Claire Murphy recruited participants and edited the manuscript. Robert Barrack and John Clohisy referred participants and edited the manuscript. Kathryn Kronquist genotyped KP participants and edited the manuscript. Susan Gatchel recruited participants and entered data. Brian Gage designed and oversaw the study, analyzed data, and helped draft the manuscript.

References

- 1.McWilliam A, Lutter R, Nardinelli C. Health Care Savings from Personalized Medicine Using Genetic Testing: The Case of Warfarin. AEI-Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higashi MK, Veenstra DL, Kondo LM, Wittkowsky AK, Srinouanprachanh SL, Farin FM, Rettie AE. Association between CYP2C9 genetic variants and anticoagulation-related outcomes during warfarin therapy. JAMA. 2002;287:1690–1698. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.13.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White RH, Beyth RJ, Zhou H, Romano PS. Major bleeding after hospitalization for deep-venous thrombosis. Am J Med. 1999;107:414–424. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00267-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Limdi NA, McGwin G, Goldstein JA, Beasley TM, Arnett DK, Adler BK, Baird MF, Acton RT. Influence of CYP2C9 and VKORC1 1173C/T genotype on the risk of hemorrhagic complications in African-American and European-American patients on warfarin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83:312–321. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Millican E, Lenzini P, Milligan P, Grosso L, Eby C, Deych E, Grice G, Clohisy J, Barrack R, Burnett R, Voora D, Gatchel S, Tiemeier A, Gage B. Genetic-based dosing in orthopaedic patients beginning warfarin therapy. Blood. 2007;110:1511–1515. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-069609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schelleman H, Chen Z, Kealey C, Whitehead AS, Christie J, Price M, Brensinger CM, Newcomb CW, Thorn CF, Samaha FF, Kimmel SE. Warfarin response and vitamin K epoxide reductase complex 1 in African Americans and Caucasians. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81:742–747. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gage BF, Eby C, Milligan PE, Banet GA, Duncan JR, McLeod HL. Use of pharmacogenetics and clinical factors to predict the maintenance dose of warfarin. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:87–94. doi: 10.1160/TH03-06-0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linder MW, Looney S, Adams JE, 3rd, Johnson N, Antonino-Green D, Lacefield N, Bukaveckas BL, Valdes R., Jr Warfarin dose adjustments based on CYP2C9 genetic polymorphisms. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2002;14:227–232. doi: 10.1023/a:1025052827305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Voora D, Eby C, Linder MW, Milligan PE, Bukaveckas BL, McLeod HL, Maloney W, Clohisy J, Burnett RS, Grosso L, Gatchel SK, Gage BF. Prospective dosing of warfarin based on cytochrome P-450 2C9 genotype. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93:700–705. doi: 10.1160/TH04-08-0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Margaglione M, Colaizzo D, D'Andrea G, Brancaccio V, Ciampa A, Grandone E, Di Minno G. Genetic modulation of oral anticoagulation with warfarin. Thromb Haemost. 2000;84:775–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rieder MJ, Reiner AP, Gage BF, Nickerson DA, Eby CS, McLeod HL, Blough DK, Thummel KE, Veenstra DL, Rettie AE. Effect of VKORC1 haplotypes on transcriptional regulation and warfarin dose. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2285–2293. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wadelius M, Chen LY, Downes K, Ghori J, Hunt S, Eriksson N, Wallerman O, Melhus H, Wadelius C, Bentley D, Deloukas P. Common VKORC1 and GGCX polymorphisms associated with warfarin dose. Pharmacogenomics J. 2005;5:262–270. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Andrea G, D'Ambrosio RL, Di Perna P, Chetta M, Santacroce R, Brancaccio V, Grandone E, Margaglione M. A polymorphism in the VKORC1 gene is associated with an interindividual variability in the dose-anticoagulant effect of warfarin. Blood. 2005;105:645–649. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan HY, Chen JJ, Lee MT, Wung JC, Chen YF, Charng MJ, Lu MJ, Hung CR, Wei CY, Chen CH, Wu JY, Chen YT. A novel functional VKORC1 promoter polymorphism is associated with inter-individual and inter-ethnic differences in warfarin sensitivity. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1745–1751. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood S. [cited 2007 Sept 4, 2007];New Warfarin Labeling Reminds Physicians About Genetic Tests to Help Guide Initial Warfarin Dosing. 2007 Available from: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/561608.

- 16.Carlquist JF, Horne BD, Muhlestein JB, Lappe DL, Whiting BM, Kolek MJ, Clarke JL, James BC, Anderson JL. Genotypes of the cytochrome p450 isoform, CYP2C9, and the vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1 conjointly determine stable warfarin dose: a prospective study. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006;22:191–197. doi: 10.1007/s11239-006-9030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sconce EA, Khan TI, Wynne HA, Avery P, Monkhouse L, King BP, Wood P, Kesteven P, Daly AK, Kamali F. The impact of CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genetic polymorphism and patient characteristics upon warfarin dose requirements: proposal for a new dosing regimen. Blood. 2005;106:2329–2333. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herman D, Peternel P, Stegnar M, Breskvar K, Dolzan V. The influence of sequence variations in factor VII, gamma-glutamyl carboxylase and vitamin K epoxide reductase complex genes on warfarin dose requirement. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:782–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gage B, Eby C, Johnson J, Deych E, Rieder M, Ridker P, Milligan P, Grice G, Lenzini P, Rettie A, Aquilante C, Grosso L, Marsh S, Langaee T, Farnett L, Voora D, Veenstra D, Glynn R, Barrett A, McLeod H. Use of Pharmacogenetic and Clinical Factors to Predict the Therapeutic Dose of Warfarin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008 doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson JL, Horne BD, Stevens SM, Grove AS, Barton S, Nicholas ZP, Kahn SF, May HT, Samuelson KM, Muhlestein JB, Carlquist JF. Randomized trial of genotype-guided versus standard warfarin dosing in patients initiating oral anticoagulation. Circulation. 2007;116:2563–2570. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.737312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caraco Y, Blotnick S, Muszkat M. CYP2C9 genotype-guided warfarin prescribing enhances the efficacy and safety of anticoagulation: a prospective randomized controlled study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83:460–470. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwarz UI, Ritchie MD, Bradford Y, Li C, Dudek SM, Frye-Anderson A, Kim RB, Roden DM, Stein CM. Genetic determinants of response to warfarin during initial anticoagulation. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:999–1008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenzini P, Grice G, Milligan P, Gatchel S, Deych E, Eby C, Burnett RS, Clohisy J, Barrack R, Gage B. Optimal Dose Adjustment in Orthopaedic Patients Beginning Warfarin Therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1798–1804. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King C, Porche-Sorbet R, Gage B, Ridker P, Renaud Y, Phillips M, Eby C. Performance of Commercial Platforms for Rapid Genotyping of Polymorphisms Affecting Warfarin Dose. Am J Clin Path. 2008 doi: 10.1309/1E34UAPR06PJ6HML. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJ, Briet E. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost. 1993;69:236–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen LH, van Leeuwen RE, van Thiel GC, van Pelt JF, Yap SH. Equally potent inhibitors of cholesterol synthesis in human hepatocytes have distinguishable effects on different cytochrome P450 enzymes. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2000;21:353–364. doi: 10.1002/bdd.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gage BF, Fihn SD, White RH. Management and dosing of warfarin therapy. Am J Med. 2000;109:481–488. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00545-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hylek EM, Evans-Molina C, Shea C, Henault LE, Regan S. Major hemorrhage and tolerability of warfarin in the first year of therapy among elderly patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2007;115:2689–2696. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.653048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siguret V, Gouin I, Debray M, Perret-Guillaume C, Boddaert J, Mahe I, Donval V, Seux ML, Romain-Pilotaz M, Gisselbrecht M, Verny M, Pautas E. Initiation of warfarin therapy in elderly medical inpatients: a safe and accurate regimen. Am J Med. 2005;118:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fennerty A, Dolben J, Thomas P, Backhouse G, Bentley DP, Campbell IA, Routledge PA. Flexible induction dose regimen for warfarin and prediction of maintenance dose. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;288:1268–1270. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6426.1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gedge J, Orme S, Hampton KK, Channer KS, Hendra TJ. A comparison of a low-dose warfarin induction regimen with the modified Fennerty regimen in elderly inpatients. Age Ageing. 2000;29:31–34. doi: 10.1093/ageing/29.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kovacs MJ, Rodger M, Anderson DR, Morrow B, Kells G, Kovacs J, Boyle E, Wells PS. Comparison of 10-mg and 5-mg Warfarin Initiation Nomograms Together with Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin for Outpatient Treatment of Acute Venous Thromboembolism. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:714–719. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-9-200305060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mungall DR, Ludden TM, Marshall J, Hawkins W, Talbert RL, Crawford MH. Population kinetics of racemic warfarin. Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Biopharmaceutics. 1985;13:213–227. doi: 10.1007/BF01065653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sconce EA, Khan TI, Daly AK, Wynne HA, Kamali F. The impact of simvastatin on warfarin disposition and dose requirements. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1422–1424. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oden A, Fahlen M, Hart RG. Optimal INR for prevention of stroke and death in atrial fibrillation: a critical appraisal. Thromb Res. 2006;117:493–499. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caldwell MD, Berg RL, Zhang KQ, Glurich I, Schmelzer JR, Yale SH, Vidaillet HJ, Burmester JK. Evaluation of genetic factors for warfarin dose prediction. Clin Med Res. 2007;5:8–16. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2007.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]