Abstract

Ion binding to secondary active transporters triggers a cascade of conformational rearrangements resulting in substrate translocation across cellular membranes. Despite the fundamental role of this step, direct measurements of binding to transporters are rare. We investigated ion binding and selectivity in CLC-ec1, a H+/Cl− exchanger of the CLC family of channels and transporters. Cl− affinity depends on the conformation of the protein: it is highest with the extracellular gate removed, and weakens as the transporter adopts the occluded configuration and with the intracellular gate removed. The central ion-binding site determines selectivity in CLC transporters and channels, a serine to proline substitution at this site confers NO3− selectivity upon the Cl− specific CLC-ec1 transporter and CLC-0 channel. We propose that CLC-ec1 operates through an affinity-switch mechanism and that the bases of substrate specificity are conserved in the CLC channels and transporters.

Keywords: Isothermal titration calorimetry, channel, transport, chloride

Introduction

Proteins mediating ion transport operate according to one of two opposing paradigms: channels form aqueous pores through which ions diffuse passively, whereas transporters catalyze substrate movement against a gradient at the expense of electrochemical energy. Translocation is mediated by sequential conformational rearrangements respectively leading to pore-opening or alternate exposure of the binding site(s). ATP binding and hydrolysis, transmembrane voltage or binding of non-permeant ligands modulate or drive the gating cycles of channels and primary transporters. In contrast, secondary active transporters dissipate the electrochemical gradient of one substrate to accumulate the other(s). Thus, substrate binding and dissociation on either side of the membrane is the primary driving force for turnover. Despite the fundamental role that substrate binding plays in the transport cycle direct binding measurements to transporters have been limited because of low substrate affinity and scarcity of the purified protein1–7, and the equilibrium binding affinity has been estimated from parameters derived from non-equilibrium measurements8–11.

The CLC family of Cl− transporting proteins encodes for both ion channels and H+/Cl− exchangers12–18 and mutations in 5 of the 9 human CLC genes lead to genetically inherited diseases19. CLC-ec1, a H+/Cl− exchanger from E. coli, is the prototypical CLC transporter. The WT protein as well as several mutants have been crystallized12,20–22 and extensively characterized functionally13,23–26. Simultaneous mutation of two gate-forming residues leads to H+-uncoupled Cl− transport at rates that are ~20-fold faster than in the wildtype transporter, possibly reflecting the conversion of CLC-ec1 from exchanger to channel27. Thus, CLC-ec1 offers the unique opportunity to directly investigate ion binding to a secondary transporter and a putative ion channel within the confines of a single, structurally defined molecular scaffold.

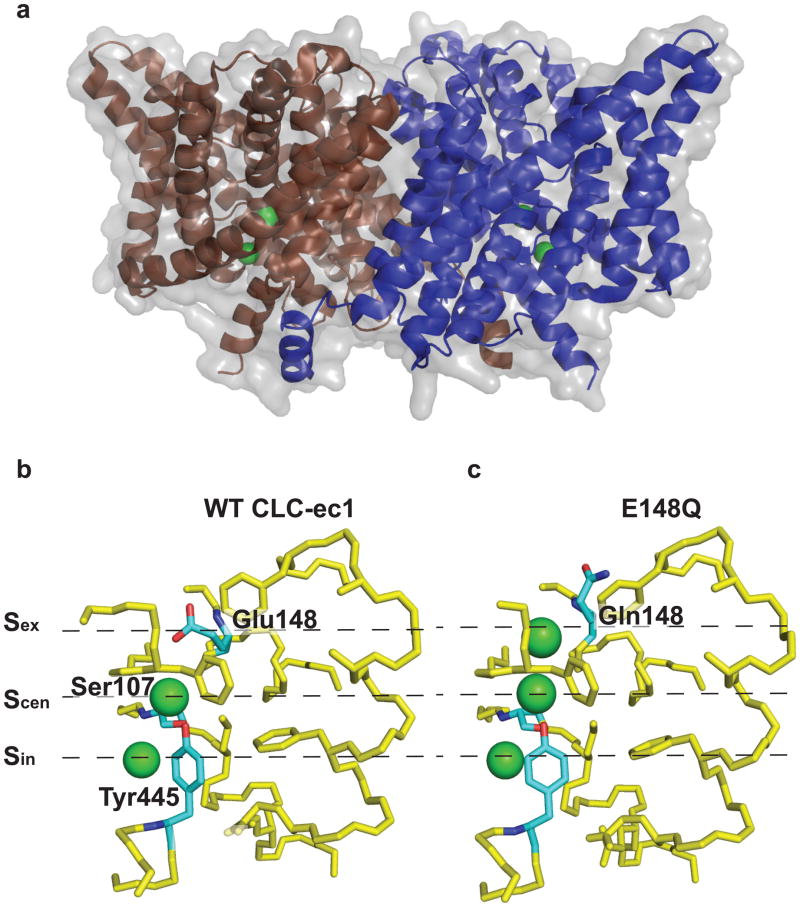

CLC-ec1 is a dimer that forms two distinct Cl− transport pathways12,20 (Fig. 1a) defined by three anion binding sites bridging the two sides of the membrane (Fig. 1b). In the WT protein, an ion in the central site, Scen, is isolated from the extracellular solution by the conserved side chain of E148 and intracellularly by the side chains of two conserved residues, S107 and Y445. This structure is thought to represent the occluded state of CLC-ec122. The ion in the intracellular site, Sin, is in direct equilibrium with the solution and its access to Scen is regulated by the conformational state of the intracellular gate, Y44522. Although the movement opening this gate is not known it has been speculated that the crystal structure of the Y445A mutant mimics an inward-facing configuration of the transporter27. During the transport cycle the external site, Sex, is alternatively occupied by a Cl− ion or by the de-protonated E148 side chain20 (Fig. 1b, c). The E148Q mutation locks the extracellular gate in the open state and the crystal structure of this mutant possibly captures the protein in its outward facing configuration20 (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of CLC-ec1. (a) Ribbon representation of the CLC-ec1 homodimer viewed from the plane of the membrane. The two subunits are coloured in brown and blue and the chloride ions are represented as green spheres. (b) The chloride binding region for the WT CLC-ec1 and (c) the E148Q mutant. The residues S107, E148 and Y445 are highlighted in blue. (PDB accession codes WT: 1OTS, E148Q: 1OTU)

A recent crystallographic study suggests that the three sites bind Cl− with affinities ranging from 2 to 30 mM21 and that they can be occupied simultaneously. However, these indirect measurements do not allow the extraction of the thermodynamic contributions regulating binding and selectivity. In order to access this fundamental information we used isothermal titration calorimetry, ITC, to directly measure ion binding to CLC-ec1. ITC has been used to probe receptor/ligand interactions in a variety of high- to moderate-affinity systems28 and can be applied to weakly binding systems, provided that external constraints are placed on the binding stoichiometry. This allows the reliable determination of the association constant, K, and the enthalpy of association, ΔH3,28–31. Since the expected Cl− affinities are relatively low21 we injected a vast excess of Cl− (50- to 400-fold molar ratio excess of ligand to receptor) and constrained the number of sites based on the appropriate known structures for CLC-ec112,20–23 (see Methods).

Results

Cl− binding to WT CLC-ec1

When KCl is injected into a chamber containing detergent-solubilized CLC-ec1 heat is liberated, as indicated by the downward deflections (Fig. 2a). This heat is due to Cl− binding to one or more of the three sites of CLC-ec1 (and any conformational changes linked to ion binding), depending on the conformation(s) adopted by the transporter. Although transport mediated by CLC-ec1 is pH-dependent32–34 (Supplementary Fig. 1a), Cl− binding is not (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table 1). We performed the ITC experiments at pH 7.5 at which transport activity is minimal13,32, Sex is predominantly occupied by E148, the conformational heterogeneity is minimized and is close to the pH at which most crystal structures of WT and mutant CLC-ec1 have been determined12,20–23, simplifying a structure-based interpretation of the data.

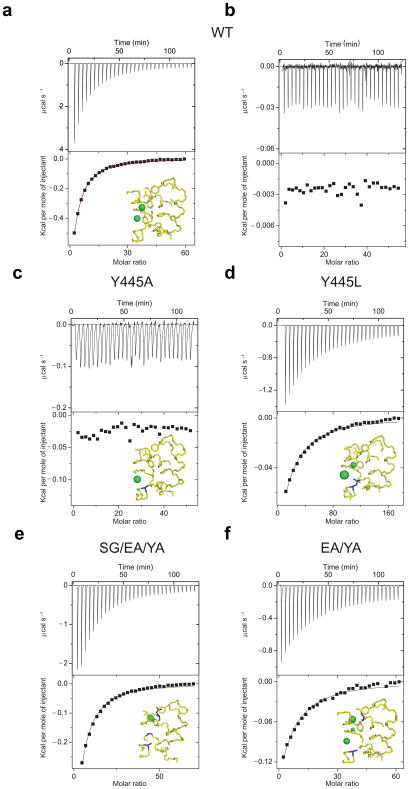

Figure 2.

Cl− binding to WT and mutant CLC-ec1. Top panels: heat liberated when KCl is titrated into the experimental chamber containing buffer and protein. The concentration of the KCl stock used was 25 mM for WT CLC-ec1, Y445A, S107G/E148Q/Y445A and E148A/Y445A mutants and 25–75 mM for the Y445L mutant. Each downward deflection corresponds to one injection. Bottom panels: the area underneath each deflection is integrated and represents the total heat exchanged (squares). Black lines are the best fits to a single site binding isotherm. (a) WT CLC-ec1. In the bottom panel the red line represents the fit to a binding isotherm with two identical sites. (b) KIsethionate binding to WT CLC-ec1. Cl− binding to the following mutants: Y445A (c), Y445L (d), S107G/E148A/Y445A (e) and E148A/Y445A (f). Insets show the structure of the ion binding site with the mutated residue(s) highlighted in blue. The structure of the S107A/E148Q/Y445A mutant is used as a model for the S107G/E148A/Y445A mutant. Green spheres represent bound Cl− ions. Following the published convention 27, the spheres occupying Scen in the Y445L and E148A/Y445A mutants are scaled down in size to reflect the reduced anion occupancy of this site in these mutants. (PDB accession codes: WT: 1OTS, Y445A: 2HTK, Y445L: 2HT3, S107A/E148Q/Y445A:2EZ0 and E148A/Y445A: 3DET)

The heat released reflects specific Cl− binding to CLC-ec1: substitution of Cl− with the inert Isethionate−26 yields no measurable heat of binding (Fig. 2b) indicating that Cl− rather than K+ binds to CLC-ec1. Based on the data alone we cannot determine whether the heat released is due to Cl− binding to Scen and/or to Sin seen occupied by halides in the crystals (Fig. 2a, inset): models with one (black line) or two (red line) identical and independent sites describe the data equally well (Fig. 2a) and yield comparable estimates of the binding affinities, 720 and 620μM respectively (Table 1). Theoretical calculations35 and crystallographic investigations21 indicated that Cl− binding to Sin is weak, Kd>20 mM, and beyond the resolution power of these measurements. We hypothesized that heat released (Fig. 2a) is associated to Cl− binding to a single site, Scen.

Table 1.

Thermodynamic parameters for Cl− binding to WT and mutant CLC-ec1. Kd and ΔH° were obtained from a fit to a binding isotherm, while ΔG° and TΔS° were calculated from ΔG°= RT lnKd and TΔS°= ΔH°−ΔG°. Each value represents the mean of three or more independent ITC experiments and the s.e.m. is reported as the error (see Supplementary Table 1 for the results of the individual experiments).

| Protein | Number of sites | Kd (μM) | ΔH° (Kcal Mol−1) | TΔS° (Kcal Mol−1) | ΔG° (Kcal Mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 1 | 720±80 | −5.3±0.3 | −1.0±0.3 | −4.3±0.1 |

| 2 | 620±70 | −2.6±0.2 | 1.8±0.2 | −4.4±0.1 | |

| Y445A | no heat detected | ||||

| Y445L | 1 | 3900±1100 | −3.4±0.8 | 0±1 | −3.3±0.2 |

| SG/EA/YA | 1 | 860±180 | −4.9±0.3 | −0.8±0.3 | −4.18±0.04 |

| EA/YA | 1 | 1520±70 | −2.1±0.2 | 1.7±0.2 | −3.84±0.03 |

| E148A | 2 | 12.3±1.7 | −6.0±0.6 | 0.7±0.5 | −6.7±0.1 |

| 1.8±0.1 | 15±2 | −6.7±0.7 | −0.1±0.6 | −6.6±0.1 | |

Cl− binding to Sin and Scen

To test this hypothesis we measured Cl− binding to the Y445A and Y445H mutants of CLC-ec122. In these mutants, halide binding to Scen is observed crystallographically to be disrupted while Sin remains largely intact (Fig. 2c, inset, Supplementary Fig. 2a), allowing us to isolate the properties of the latter. No heat of Cl− binding to either mutant is detected (Fig. 2c), indicating that Sin is a weak site with a Kd>20 mM. Lowering the temperature to 10 °C weakly enhances Cl− binding to the Y445A mutant (Supplementary Fig. 2b). These results confirm that the heat liberated when KCl is injected in a chamber containing WT CLC-ec1 is due to Cl− binding to Scen with a Kd~720μM. This process is enthalpically driven, ΔH~ −5.3 Kcal Mol−1, with a small entropic contribution, TΔS~−1.0 Kcal Mol−1 (Table 1).

To further test this conclusion we measured Cl− binding to another mutant, Y445L, in which anion binding to Scen is only partlydestabilized22 (Fig. 2d, inset). If the heat released only reflects Cl− binding to Scen then the affinity of this mutant should be intermediate between those of the WT and the Y445A/H mutants. This is the case. The total heat is described by a single-site isotherm with a Kd~3.9 mM, ~6-fold higher than that of the WT (Fig. 2d) and >5-fold lower than that of the Y445A/H mutants. Thus, the heat liberated upon Cl− binding to CLC-ec1 reflects the properties of Scen alone.

Cl− binding to Sex

Having determined the Cl− affinity of Scen and Sin we turned our attention to Sex. It is not possible to directly measure ionbinding to this site in the WT protein since Cl− and the E148 side chain compete for Sex. However, in the triple mutant S107A/E148Q/Y445A Sex is the only site occupied by halides21 (Fig. 2e, inset). This mutant protein however was not stable over the course of an ITC experiment. Thus, we used the more stable and analogous mutant S107G/E148A/Y445A to investigate the binding properties of Sex. Cl− binding to this mutant is well described by a single-site isotherm with a Kd~0.9 mM (Fig. 2e) and is enthalpically driven (Table 1). Thus, the isolated Scen and Sex have similar thermodynamic properties.

To test this conclusion we measured Cl− binding to the E148A/Y445A double mutant (Fig. 2f) in which anion binding to Scen is destabilized while binding to Sex and Sin is unaltered27 (Fig. 2f, inset). Since our previous results indicated that Cl− binding to Sin is weak (Fig. 2c) we expected the Kd of the E148A/Y445A mutant to be close to that of the triple mutant. Indeed, Cl− binding to the double mutant is well described by a single site model (Fig. 2f) with a Kd ~1.5 mM (Table 1), a value close to that of the triple mutant. Fitting with a 2-site model does not influence the Kd (not shown). Thus Cl− binds to Sex with a Kd ~1 mM and independently of Sin.

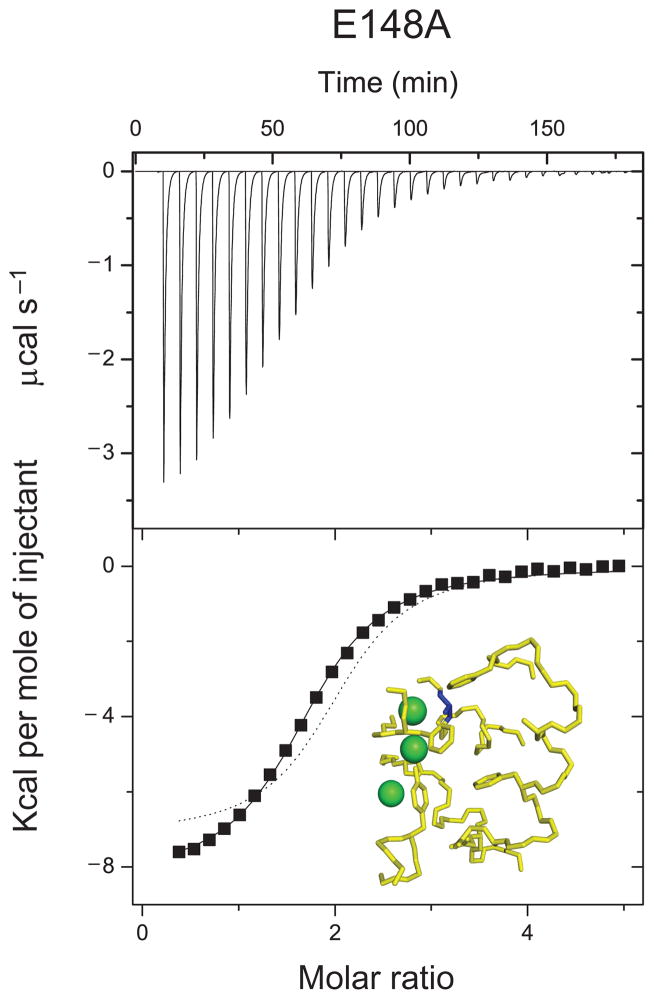

Cl− binding to the E148A mutant

With the characterization of the isolated sites in place we investigated how multiple occupancy affects ion binding by measuring Cl− binding to a mutant, E148A, in which all three sites can be occupied by ions20,21. We expected Cl− to bind to the E148A mutant similarly to the WT or weaker because of the electrostatic repulsion between the multiple negative charges (Fig. 3a, inset). Unexpectedly, we found that Cl− binds to the E148A mutant more tightly than to the WT protein. The binding curve assumes the typical sigmoidal shape of an ITC saturation binding experiment reaching its mid-point at a molar ratio ~2 and saturating at a molar ratio of ~3 (Fig. 3a), much earlier than in the WT (Fig. 2a).This suggests that we detect Cl− binding to two of the three available sites, most likely Scen and Sex. One- or three-site binding isotherms yield poor fits (not shown). The data is described reasonably well by a model with two identical and independent sites with a Kd of ~12μM (Fig. 3a, dashed line; Table 1), a 60–100 fold increase in affinity compared to the isolated Scen and Sex sites. The increase in free energy of Cl− binding to the E148A mutant compared to the WT protein, ~2.4 Kcal Mol−1, is due to changes in both the enthalpy and entropy of binding (Table 1). The changes in the enthalpy could partly result from the altered coupling of Cl− and H+ binding33. The increased affinity of this mutant allows for the determination of the number of binding sites directly from the data30. The best fit is for n~1.8 (not shown), in good agreement with the previous conclusion that Cl− binds to two sites. A similar increase in Cl− affinity is seen with the more conservative mutation E148Q20 (Supplementary Fig. 2c, Supplementary Table 1) suggesting that this effect is not specific to the alanine substitution.

Figure 3.

Cl− binding to the E148A mutant. Panels as in Figure 2. A KCl solution is titrated into a chamber containing the E148A mutant. The concentration of the KCl stock used was 5–25 mM. Dashed line: fit to a binding isotherm with 2 identical and independent sites. Solid line: fit to a binding model with n, ΔH and K as free parameters. (PDB accession code E148A: 1OTT)

These measurements show that multiple Cl− ions bind simultaneously to the permeation pathway of CLC-ec1 with higher affinity than a single ion.

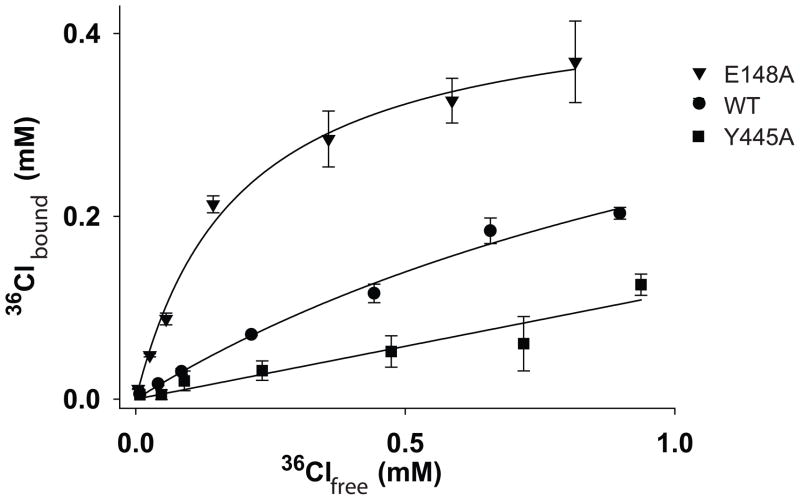

36CL binding measured with saturation equilibrium dialysis

The increased affinity of the E148A mutant was so unexpected that we felt compelled to validate it using a different approach, saturation equilibrium dialysis36. We measured 36CL binding to WT, Y445A and E148A immobilized on Co2+ beads through an intact His-tag. In good agreement with our ITC results 36CL binds to the E148A mutant more tightly than to the WT protein and very weakly to the Y445A mutant (Fig. 4) with respective Kd’s of ~190 μM, ~1.4 mM and >20 mM. This confirms that the increase in affinity seen with the E148A mutant reflects a true property of the mutated protein. The measured values are in qualitative agreement with those measured with ITC (Table 1). The quantitative discrepancy is particularly large for the E148A mutant, > 10-fold. While we don’t have a definitive explanation for this inconsistency we think that differences in the experimental set-ups might account for it. The ITC measurements were performed on protein without the His-tag while the equilibrium dialysis is performed on protein with the His-tag and is bound to the Co2+ beads. Since the tag is at the end of helix R, which lines the intracellular vestibule12, it is possible that the Histidines and the Co2+ beads influence the electric field at the binding sites. Consistent with this, an intact His-tag lowers the affinity of Cl− for WT CLC-ec1 ~2-fold in ITC experiments (not shown). We could not perform this control on the E148A protein with the His-tag since it is not stable. Despite this difference the two experimental approaches show a similar trend where Cl− binding to the WT protein is in the millimolar range and is weakened in the Y445A mutant and enhanced by mutation E148A.

Figure 4.

36CL binding measured with equilibrium dialysis. Circles: binding to WT CLC-ec1; triangles: binding to the E148A mutant and squares: binding to the Y445A mutant. Solid lines are the best fits to 36CLbound= 36CLmax/(1+Kd/36CLfree).

Binding selectivity of CLC-ec1

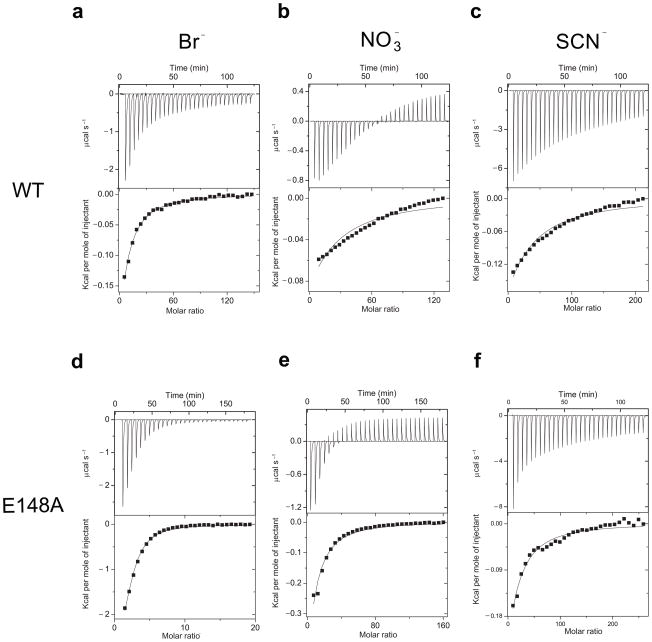

The above results suggest that subtle structural differences existing between WT and mutant CLC-ec1 lead to drastic changes of Cl− occupancy and affinity. Do these changes also alter anion binding selectivity of CLC-ec1, or do different elements regulate affinity and selectivity? To address this issue we measured Br−, NO3− and SCN− binding to WT and mutant CLC-ec1 (Fig. 5a–c). These anions bind to WT CLC-ec1 more weakly than Cl− and a single-site binding isotherm describes the heat exchanged with estimated affinities, Kd(Br−)~2.6 mM > Kd(SCN−)~9.2 mM ~ Kd(NO3−)~13 mM (Table 2) that resemble the anion transport sequence24,33. Furthermore, H+-coupling degrades as anion binding weakens: stronger binders (Cl− and Br−) support tight coupling while weaker binders (NO3− and SCN−) degrade coupling24. For the weakly interacting anions the binding reaction does not saturate completely, preventing a precise determination of the enthalpy and entropy of binding. Thus, the values reported in Table 2 are only qualitative estimates. The measurement of the affinity, however, is robust and reliable (see Methods).

Figure 5.

Binding selectivity of WT CLC-ec1 and the E148A mutant. Panels as in Figure 2. The concentrations of the stocks used was: [KBr]WT=100 mM, [KBr]E148A=10–40 mM, [KNO3]WT=100–200 mM, [KNO3]E148A=75–100 mM, [KSCN]WT=[KSCN]E148A=100 mM. (a) Br− binding, (b) NO3− binding and (c) SCN− binding to WT CLC-ec1. Anion binding to the E148A mutant: (d) Br−, (e) NO3− and (f) SCN−. Solid lines represent the best fits to a 1- or 2-site binding isotherm respectively for WT and the E148A mutant.

Table 2.

Thermodynamic parameters for anion binding to WT and mutant CLC-ec1. Thermodynamic parameters, Kd, ΔHo, TΔS° and ΔG° are determined as described in Table 1, and by fixing n=1 for WT, Y445A and S107P. We fixed n=2 for the E148A mutant since the affinity of Br−, NO3− and SCN− is not sufficient to allow for the independent determination of the number of binding sites.

| Protein | Anion | Kd (μM) | ΔH° (Kcal Mol−1) | TΔS° (Kcal Mol−1) | ΔG° (Kcal Mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Br− | 2550±530 | −5.0±0.6 | −1.4±0.5 | −3.6±0.1 |

| NO3− | 13000±1500 | −6.9±1.2* | −4.3±1.2* | −2.6±0.1 | |

| SCN− | 9200±400 | −15.6±0.1* | −12.8±0.1* | −2.78±0.03 | |

| Y445A | Br− | no heat detected | |||

| NO3− | no heat detected | ||||

| SCN− | 6700±200 | −21.0±0.6* | −18.2±0.6* | −2.96±0.02 | |

| E148A | Br− | 84±16 | −3.4±0.9 | 2.2±1.0 | −5.6±0.5 |

| NO3− | 1400±300 | −5.1±0.5 | −1.2±0.6 | −3.9±0.1 | |

| SCN− | 5800±1200 | −7.7±1.6* | −4.7±1.5* | −3.1±0.1 | |

| S107P | Cl− | no heat detected | |||

| Br− | no heat detected | ||||

| NO3− | 3800±800 | −2.9±0.7 | 0.5±0.6 | −3.3±0.1 | |

| SCN− | 8000±1500 | −15.1±1.7* | −12.2±1.8* | −2.9±0.1 | |

These enthalpy and entropy values are only estimates since the binding reaction could not be driven to complete saturation. Each value represents the mean of three or more independent ITC experiments and the s.e.m. is reported as the error (see Supplementary Table 1 for the results of the individual experiments).

We next measured the selectivity of the E148A mutant to assess whether the changes in affinity were mirrored by an altered specificity. The binding selectivity of the E148A mutant is the same as WT’s (Fig. 5d–f; Table 2). However, while the mutant binds Cl−, Br− and NO3− more tightly than the WT the affinity of SCN− is nearly unchanged (Table 2). The lack of effect of the E148A mutation on SCN− binding is consistent with the observation that this anion binds only to Sin in both WT and E148A mutant24. This hypothesis is confirmed by the observation that SCN− binds to the Y445A mutant with a similar affinity, while Cl−, Br− and NO3− do not bind (Table 2; Supplementary Fig. 2d–f). This shows that Sin is a mildly selective site that prefers SCN− to Cl−. These results show that E148 and simultaneous occupancy of Scen and Sex regulate affinity but not selectivity.

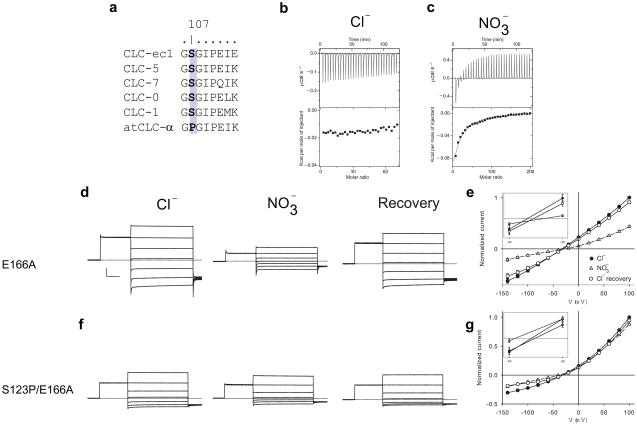

Determinants of selectivity in CLC transporters and channels

The previous conclusion raises the question of which structural elements determine selectivity in CLC-ec1? In the plant CLC homologue atCLC-α, which preferentially transports NO3− over Cl−17,37, the serine participating to Scen (Fig. 1b) is suggestively replaced by a proline (Fig. 6a). We introduced the corresponding mutation in CLC-ec1 and investigated its consequences on anion binding. The S107P mutant is functional and retains the basic characteristics of CLC transporters, although Cl−/H+ exchange is slowed ~8-fold (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c). We found that Cl− and Br− do not bind to the S107P mutant (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 3d) whereas NO3− binding to the mutant is enhanced ~4-fold (Fig. 3c), Kd ~3.8 mM. SCN− binding is nearly unaltered (Supplementary Fig. 3e), confirming that Sin favors this anion over Cl−. Thus, through a single point mutation, S107P, we conferred the selectivity of the plant NO3−/H+ transporter atCLC-α onto CLC-ec1.

Figure 6.

S107 regulates selectivity. (a) Alignment of the linker region between helices C and D in several CLC channels and transporters; the position corresponding to S107 is highlighted in bold on a grey background. (b–c) Panels as in Figure 2. The concentrations of the stocks used was: [KCl]=25 mM, [KNO3]=50–75 mM. (b) Cl− binding to the S107P mutant. (c) NO3− binding to the S107P mutant. (d) Currents mediated by the E166A mutant of CLC-0 in 100 mM external Cl− (left), NO3− (center) and after recovery in Cl− (right). From a holding potential of −30 mV the voltage is stepped to +80 mV for 100 ms and then to a variable voltage increasing from −140 to +100 mV in 20 mV steps for 200 ms. Horizontal scale bar indicates 30 ms and vertical scale bar indicates 2 μA. e) Steady state I–V relationship for the E166A mutant in Cl− (filled circles), NO3− (open triangles) and after recovery in Cl− (empty circles). Inset: the I–V curves are magnified to highlight the shift in reversal potential. The solid and dashed lines hold no theoretical meaning and are for visualization purposes alone. The reversal potentials, Vrev, were derived from a linear interpolation of the curve around the null current point and represent the average of 6 or more independent experiments and the Standard Error of the Mean is shown as error. VrevE166A(Cl−)=−32±2 mV, VrevE166A(NO3−)=−27±3 mV and VrevE166A(Cl−, recovery)=−31±2 mV. f) Currents mediated by the S123P/E166A mutant in 100 mM external Cl− (left), in NO3− (center) and after recovery in Cl− (right). g) Steady state I–V relationship for the S123P/E166A mutant in Cl− (filled circles), NO3− (open triangles) and after recovery in Cl− (empty circles). VrevS123P/E166A(Cl−)= −31±2 mV, VrevS123P/E166A(NO3−)= −39±2 mV and VrevS123P/E166A(Cl−, recovery)= −31±3 mV. Each value represents the mean of three or more independent experiments and the s.e.m. is reported as the error (see Supplementary Table 1 for the results of the individual experiments).

To test whether this serine modulates selectivity only in the CLC transporters, or if it has an equivalent role also in the CLC channels we introduced the corresponding mutation, S123P, into the CLC-0 channel. However, no currents were detectable when we injected this mutant in Xenopus oocytes (not shown). To test whether this was due to protein mis-folding, a drastically reduced single channel conductance38 or to a constitutive closure of the channel due to a reduced affinity of Cl− for CLC-039,40 we introduced the S123P mutation in the background of the constitutively open CLC-0 mutant, E166A (Fig. 6d–e). The S123P/E166A double mutant mediates robust anionic currents in Xenopus oocytes (Fig. 6f–g). Since the E166A mutation alone does not alter single channel conductance or selectivity20,41 it constitutes the ideal template to isolate effects on permeation from those on gating. Ion substitution experiments show that NO3− is both less conductive and less permeant than Cl− through the WT and E166A mutant pore: replacement of the external Cl− with NO3− leads to a >60% reduction in the current at +100 mV and to a ~+5 mV shift in the reversal potential (Fig. 6e, Supplementary Fig. 4). In contrast, Cl− and NO3− permeate equally well through the S123P/E166A mutant pore (Fig 6g): the currents at +100 mV are nearly identical and there is a ~ −8 mV shift in the reversal potential, indicating that NO3− has become slightly more permeant in the mutant.

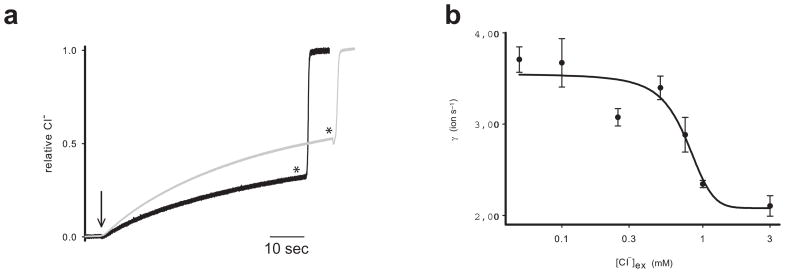

Cl− dependence of the transport rate of CLC-ec1

The data described so far shows that Cl− binds to detergent-solubilized WT CLC-ec1 with a Kd ~0.72 mM. However, the relationship between our equilibrium measurements and transport –an out-of-equilibrium process– mediated by the protein embedded in a lipid bilayer remains unclear. To address this issue we determined the transport rate of CLC-ec1 reconstituted in proteo-liposomes at [Cl−]ex ranging from 50 μM to 3 mM using the “Cl− efflux” assay26. The original experiments were performed in 1 mM Cl−ex which was thought to be sufficiently low to approximate unidirectional efflux26. Our binding measurements, however, suggest otherwise: since the [Cl−]ex used in those experiments exceeds the Kd of Cl− for CLC-ec1 flux might not be unidirectional and there could be substantial Cl− backflow into the vesicles –leading to an under-estimation of the rate. Such a situation predicts that the net Cl− efflux rate should increase at lower [Cl−]ex. This is the case: when [Cl−]ex is lowered from 1 to 0.1 mM transport becomes ~2-fold faster (Fig. 7a). The dependence of the transport rate from [Cl−]ex (Fig. 7b) is well described by a Hill equation with an apparent Kd of 0.76 mM, in excellent agreement with the equilibrium Kd of 0.72 mM. The Hill coefficient of ~2.4 suggests that during transport Cl− can simultaneously bind to up to 3 interacting sites, in agreement with the current transport models for CLC-ec113,20,42.

Figure 7.

Chloride dependence of the transport rate. (a) Time course of chloride efflux from liposomes reconstituted at low protein density in 1 mM external chloride (black line) and 0.1 mM external chloride (gray line). Downward arrow denotes the addition of 1 μl of 1 mg/ml Valinomycin/FCCP (carbonylcyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone). * denotes the addition of 40 μl of 50 mM b-Octyl-Glucoside to dissolve the liposomes. (b) Transport rate versus external chloride concentration. Solid line is the best with a Hill equation with a Hill coefficient of n=2.4.

These measurements show that the properties of Cl− binding measured in detergent-solubilized protein at equilibrium correspond to those of a rate-limiting step of the conformational cycle of CLC-ec1 in a lipid bilayer confirming the fundamental role of ion binding in transport.

Discussion

Ion binding and dissociation are fundamental but understudied steps regulating the conformational cycle of secondary active transporters. Here we examined the thermodynamic basis of selective anion binding to CLC-ec1, the prototypical CLC-type H+/Cl− exchanger, and related these equilibrium properties to the transport cycle. The central and external sites have similar properties: enthalpy drives Cl− binding to both sites with comparable affinities. The inner site, on the other hand, binds Cl− only weakly and is unaccessible to our measurements. These conclusions are in harmony with those reached by Lobet and Dutzler21 who measured halide binding to CLC-ec1 by looking at the peak-height of the anomalous diffraction signal at different Br− concentrations. The discrepancies are small, 2–4 fold, and probably due to differences in the experimental set-ups. The remarkable correspondence between the binding constant of WT CLC-ec1 and the apparent affinity derived from the Cl− dependence of the transport rate suggests that the equilibrium measurements capture the functionally rate-limiting binding step.

Our findings, however, differ greatly from expectations and from the crystallographic data on the binding properties of the E148A mutant. In this protein all three sites can be simultaneously occupied by Cl− ions21 and the crystallographic experiments suggested that halides bind to the E148A mutant with affinity comparable to the WT21. However, the strong electrostatic repulsion between three ions within the translocation pathway should reduce the binding affinity. In contrast to these expectations, our measurements show a 10–60 fold increase in affinity. While we don’t have a definitive explanation for this difference, several factors might account for it. First, the increased affinity reflects a ~2.4 Kcal Mol−1 change in the free energy of binding, which could be caused by alterations in the structure, or in the pKa’s of the residues near these sites, which are too subtle to be detected at the present limited resolutions, 2.8–3.5 Å20,21. Second, the crystal contacts and/or binding of the FAB could favor a conformation other than the dominant one in solution or in the membrane. Third, the affinity of CLC-ec1 for Cl− in the crystals was determined by looking at Cl− binding to a pathway fully occupied by Br− ions21. In contrast, our experiments measure the free energy of binding to the un-occupied sites. Three lines of evidence presented here argue that mutations at position E148 enhance ionbinding. First, ITC and equilibrium dialysis show an increased Cl− affinity for the E148A mutant compared to the WT. Second, replacing E148 with an alanine or a glutamine leads to a similar increase in Cl− affinity and, third, different anions (Cl−, Br− and NO3−) bind more tightly to the E148A mutant than to the WT. Thus, multiple ions simultaneously bind to the permeation pathway with higher affinity than a single ion. This can be achieved through subtle structural alterations that compensate and stabilize the electrostatic repulsion between Cl− ions bound to Scen and Sex. In other words, these calorimetric measurements are extremely sensitive to small changes, more so than low resolution crystal structures. The unexpected low transport rate of the E148A mutant27 could reflect its increased binding affinity: reduced Cl− unbinding rate from the protein can lead to slower transport.

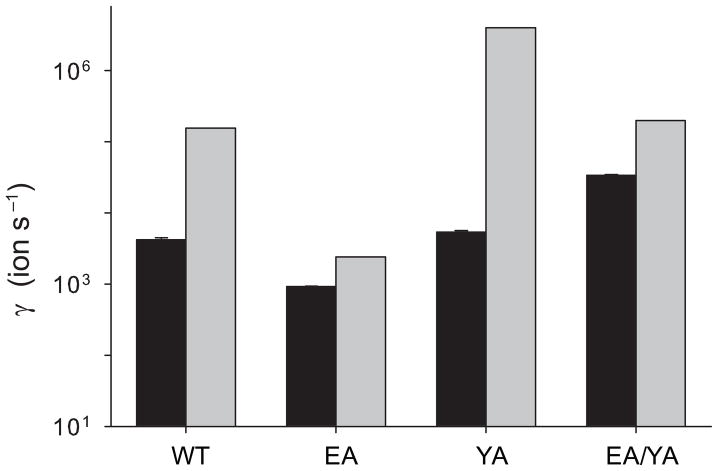

The qualitative correlation between binding and transport can be expanded into a semi-quantitative argument by making two assumptions. If binding is diffusion-limited then the maximal dissociation rate, koffmax, can be estimated from the Kd since koffmax=Kd·kondiff. If all ion dissociation events result in transport then koffmax corresponds to the transport rate. Both assumptions represent limiting cases: ligand binding to a site deep within a protein might be limited by factors other than diffusion and not all binding events result in transport. Since neither process can take place at rates faster than those assumed here then koffmax constitutes the theoretical ceiling for the transport rate. Thus a comparison of the known transport rates for WT and mutant CLC-ec126,27 with their respective upper limits can help us to identify the rate-limiting steps for transport (Fig. 8). In WT and Y445A CLC-ec1 transport takes place at rates which are similar and ~2–3 orders of magnitude slower than diffusion-limit. This argues that transport by these proteins is rate-limited by a conformational change rather than ion dissociation. At Cl− concentrations below the Kd ion binding is not diffusion-limited and becomes rate-limiting (Fig. 7). Removal of the inner gate, through the Y445A mutation, has no effect on the transport rate suggesting that opening of the outer gate, E148, is the rate-determining step. Conversely, in the E148A mutant transport is slowed down and koffmax is drastically reduced so that they become comparable, ~103 ion s−1 (Fig. 8), indicating that Cl− dissociation takes place at rates similar to, or slower than, the protein’s conformational changes. In other words, the E148A mutant is a slow transporter because it binds Cl− tightly. Finally, in the doubly ungated mutant, E148A/Y445A, koffmax and the measured transport rate are very close (Fig. 8): the latter is only 5-fold slower than the diffusion limited rate for the E148A/Y445A mutant. Thus, this mutant allows passive movement of Cl− ions at rates approaching diffusion-limitation. This suggests that this protein indeed functions as an ion channel, as originally proposed27, and that its low conductance reflects its relatively high affinity for the permeant ion.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the measured transport rates (black bars) with the theoretical maximal dissociation rate, koffmax, (grey bars) derived from koffmax=Kd*kondiff. The known transport rates were taken from published work26,27.

While the exact conformational changes taking place during the transport cycle of CLC-ec1 remain unclear it has been proposed that the WT structure captures the occluded state of the transporter. Removal of the side chain of either gate-forming residue, E148 and Y445, respectively opens the Cl− transport pathway towards the extra- or intra-cellular side. Thus, the structures of the E148A and Y445A mutants can be utilized as imperfect models for the outward- and inward-facing conformations of the protein20,27,33. Under these assumptions the Cl− affinity appears to be highest in the protein’s outward facing conformation, and sharply decreases when it transitions to the occluded and then into the inward-facing conformations. This suggests that CLC-ec1 operates according to an affinity-switch mechanism like that seen in the Ca2+ or in the Na+/K+ ATP-ases43–46. We propose that CLC-ec1 is a thermodynamically-reversible molecular machine that has a preferred direction of transport: inward anion flux is kinetically favored over outward movement. One prediction stemming from this hypothesis is that CLC-ec1 should rectify. Consistent with this, oriented CLC-ec1 currents recorded in planar lipid bilayers are mildly rectifying47. This proposal suggests that the varying degrees of rectification seen in the CLC-transporters17,19,47 could arise from changes in substrate affinity in the different conformational states. This provides a mechanistic base for rectification in the CLC-transporters which can be alternative or complementary to the proposal that rectification arises from the voltage-dependence of H+ movement48. The preferential Cl− influx coupled to H+ efflux catalyzed by CLC-ec1 are also in harmony with its proposed function in facilitating E. coli’s survival to extreme acid shocks32,49 and would provide the net Cl− influx necessary to promote function of the decarboxylating enzymes that ultimately guarantee the bacterium’s survival to the acid challenges50.

Proper function of the CLC channels and transporters is strongly substrate-dependent; different anions drastically alter gating in the channels39,51–53 and support different degrees of H+-coupling in the transporters24. Thus, understanding the molecular origin of selectivity is essential to understand the transport puzzle. Our data suggests that only one of the three binding sites determines anion selectivity in CLC-ec1. Sex12,20 does not appear to be very selective, since two anions as different as a Cl− ion and a glutamate side chain are naturally found bound to it and Sin slightly prefers SCN− to Cl−, ruling them out as the principal determinants of selectivity. Our data suggests that substrate specificity is determined at Scen: the WT protein and the E148A mutant have similar selectivity and one of the three residues forming this site, S107, modulates selectivity. We transformed the Cl− selective CLC-ec1 exchanger and the CLC-0 channel54 into NO3−-selective transport proteins by mutating their naturally occurring serine at this position into a proline. The intrinsic NO3− permeability of atCLC-α and CLC-5 is higher than for Cl−17,54,55 and a serine or a proline in the binding site only determines the extent of the preference54,55, while a proline is essential to ensure robust NO3−/H+ coupling17,55. Thus, the molecular bases of selectivity are conserved between the CLC channels and transporters in spite of the dramatic alterations undergone by these proteins to support thermodynamically opposite mechanism of ion transport. Furthermore, a clear distinction emerges between the structural elements regulating ion translocation, E148 and Y445, and those involved in substrate recognition, S107. Through this residue nature appears to manipulate the selectivity of the CLCs to allow them to fulfill their physiological roles.

Methods

Protein purification: Expression and purification of CLC-ec1 is performed according to the published protocols22,23,33. The protein was run on a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated in 100 mM Na-K-Tartrate, 20 Tris– H2SO4, 5 mM DM, pH 7.5 (buffer R) and concentrated to 70–140 μM immediately prior to the ITC experiments. Binding measurements with Isothermal Titration Calorimetry: All ITC measurements were performed with a VP-ITC Titration Calorimeter from Microcal, Inc. ~1.4 ml of concentrated protein in buffer R was added to the experimental chamber. The injection syringe is filled with buffer R to which 5–200 mM of the K+-salt of the desired monovalent anion has been added. The concentration is calculated based on the desired final molar ratio of injectant to CLC-ec1. Each experiment consists of 25–35 injections of 3–10 μl of the ligand solution at 4 min intervals into the experimental chamber that is kept under constant stirring at 350 rpm and at 25.0±0.1 °C. All solutions were filtered and degassed prior to use. The protein was extensively dialyzed between runs and re-used. No difference could be observed in activity and binding properties before or after up to 4 separate experiments. Fitting ITC data: ITC measurements are ideally performed in a regime where the product of the association constant and the receptor concentration, a parameter called c, is in the range of 5–100028–30. In this regime the number of sites, n, the association constant, K, and the enthalpy of association, ΔH, can be determined independently. For c<5 it is still possible to reliably determine K and ΔH but outside constraints on the binding stoichiometry are needed30,31. Since in the present measurements c<1 the number of binding sites was fixed based on the available crystal structures with the sole exception of the E148A mutant for which c~9. The heat liberated following the injection of salt into the experimental chamber containing solubilized CLC-ec1 is due to the combination of three processes: anion transfer from solution to the protein, salt dilution from the injection syringe into the reaction chamber and dilution of the protein in the buffer. The heat of dilution of the protein alone was determined by injecting buffer with no ligand present into a chamber containing 70–100 μM protein (Supplementary Fig. 5a); WT and mutant CLC-ec1 were undistinguishable (not shown). The heats of dilution of the salts were determined by injecting salt into the chamber containing no protein (Supplementary Fig. 5b–e). We performed at least 2 independent determinations of the heats of dilution for each salt concentration used. The appropriate heats of dilution of protein and salt were then subtracted from each experiment. In all cases there is a small, but measurable, excess heat that prevents the determination of the enthalpic and entropic contributions to the energy of weakly binding anions (Supplementary Methods).

The data was fitted to the Wiseman isotherm using the Origin ITC analysis package by keeping n fixed based on the available crystal structures. The change in heat during the ith injection was fit to:

where Q(i) is the heat liberated at the ith injection and is given by:

where n is the number of identical and independent binding sites, K is the binding constant, V0 is the active cell volume, Mt is the bulk concentration of the protein and Xt is the bulk concentration of the ligand. Further details on the fitting procedures and routines are described in the VP-ITC manual (Microcal Inc.). Saturation equilibrium dialysis. Protein purification is carried out as described except that there is no LysC incubation to maintain the His-tag and gel filtration is carried out in 100 mM NaCl, 20 Tris– H2SO4, 5 mM DM, pH 7.5 (buffer C). After gel filtration the protein is then concentrated to ~100μM and incubated for 1 hr at room temperature with 50 μl Co2+-beads (Talon) pre-equilibrated in buffer C for 1 mg of protein. The fraction of lost protein was determined by measuring the OD280 of the supernatant and the protein concentration in the sample was subsequently adjusted. In all cases this led to a correction <10%. Cl− was removed by 6 sequential washes in 250 μl of buffer R per mg of protein. Finally, the Co2+ beads are re-suspended to a final volume of 120 μl of buffer R per mg of protein. To this suspension, increasing concentrations of 36CL are added and after 1hr incubation at room temperature under constant shaking the slurry is spun for 120 sec at 13000 rpm to pellet the Co2+ beads. The total volume is split in two 60 μl aliquots, supernatant and beads, which are separately counted for 1 minute. The 36CLfree is determined from the supernatant and the 36CLbound is determined by subtracting the 36CLfree from the counts of the beads aliquot. The counts are converted into a 36CL concentration by dividing them by the activity coefficient of 36CL (0.134 mCi/ml for the original stock) and the sample volume. The 36CLbound fraction is then plotted as a function of the 36CLfree and fit to: 36CLbound=(Bmax*36CLfree)/(Kd+36CLfree). Since the specific activity of 36CL is low we could not go below 10 μM as the counts became indistinguishable from background. Non-specific 36CL binding to the Co2+-beads was negligible. Cl− and H+ flux measurements were carried out as previously described 26,33. Mutagenesis. All mutagenesis is carried out with the Quickchange method (Stratagene) and the mutated genes fully sequenced. Two electrode voltage clamp measurements: collagenase-treated Xenopus oocytes were injected with 55 nl of 50–150 mg/ml RNA of WT or mutant CLC-0 and kept at 18 °C in a solution containing 90 NaCl, 10 Hepes, 2KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, pH 7.5. Recordings were performed 2–3 days after injection. The external recording solution is 100 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgSO4, 10 mM Na-Hepes, pH 7.3. For the ion substitution experiments the NaCl was replaced with 100 mM NaNO3−. The data was acquired with the GePulse software (developed by M. Pusch) and analyzed using Ana (developed by M. Pusch) and Sigmaplot (SPSS Inc.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Chris Miller (Brandeis University) for unrelenting constructive criticism and for the generous gifts of the CLC-ec1 and CLC-0 clones, Kevin Campbell, Sarah England, Shahram Khademi, Rams Subramanian and Deborah Segaloff for comments on the manuscript, John Lueck for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript, Christine Blaumueller for expert editing and Christopher Hills for technical assistance. This work was supported by grant 1R01GM085232 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to A.A.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

A.A. designed research; A.P., M.M. and A.A. performed experiments; A.P., M.M., J.H. and A.A. analyzed the data; A.P. and A.A. wrote the paper.

Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Price WS, Kuchel PWC, BA A 35Cl and 37Cl NMR study of chloride binding to the erythrocyte anion transport protein. Biophys Chem. 1991;40:8. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(91)80030-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fang Y, Kolmakova-Partensky L, Miller C. A bacterial arginine-agmatine exchange transporter involved in extreme acid resistance. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610075200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lockless SW, Zhou M, MacKinnon R. Structural and Thermodynamic Properties of Selective Ion Binding in a K+ Channel. PLoS Biology. 2007;5:e121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boudker O, Ryan R, Yernool D, Shimamoto K, Gouaux E. Coupling substrate and ion binding to extracellular gate of a sodium-dependent aspartate transporter. Nature. 2007;445:7. doi: 10.1038/nature05455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nie Y, Smirnova I, Kasho V, Kaback HR. Energetics of ligand-induced conformational flexibility in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35779–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607232200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh S, Yamashita A, Gouaux E. Antidepressant binding site in a bacterial homologue of neurotransmitter transporters. Nature. 2007;448:5. doi: 10.1038/nature06038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh S, Piscitelli C, Yamashita A, Gouaux E. A competitive inhibitor traps LeuT in an open-to-out conformation. Science. 2008;322:7. doi: 10.1126/science.1166777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hille B. Ion channels of excitable membranes. Sinauer; Sunderland, Mass: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiFrancesco D, Tortora P. Direct activation of cardiac pacemaker channels by intracellular cyclic AMP. Nature. 1991;351:3. doi: 10.1038/351145a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magleby K. Gating mechanism of BK (Slo1) channels: so near, yet so far. J Gen Physiol. 2003;121:15. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nimigean C, Shane T, Miller C. A cyclic nucleotide modulated prokaryotic K+ channel. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124:7. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dutzler R, Campbell EB, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. X-ray structure of a ClC chloride channel at 3.0 Å reveals the molecular basis of anion selectivity. Nature. 2002;415:287–294. doi: 10.1038/415287a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Accardi A, Miller C. Secondary active transport mediated by a prokaryotic homologue of ClC Cl− channels. Nature. 2004;427:803–807. doi: 10.1038/nature02314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Picollo A, Pusch M. Chloride/proton antiporter activity of mammalian CLC proteins ClC-4 and ClC-5. Nature. 2005;436:420–423. doi: 10.1038/nature03720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scheel O, Zdebik AA, Lourdel S, Jentsch TJ. Voltage-dependent electrogenic chloride/proton exchange by endosomal CLC proteins. Nature. 2005;436:424–427. doi: 10.1038/nature03860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller C. ClC chloride channels viewed through a transporter lens. Nature. 2006;440:484–489. doi: 10.1038/nature04713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Angeli A, et al. The nitrate/proton antiporter AtCLCa mediates nitrate accumulation in plant vacuoles. Nature. 2006;442:939–942. doi: 10.1038/nature05013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graves A, Curran P, Smith C, Mindell J. The Cl−/H+ antiporter ClC-7 is the primary chloride permeation pathway in lysosomes. Nature. 2008;453:5. doi: 10.1038/nature06907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jentsch TJ. CLC chloride channels and transporters: from genes to protein structure, pathology and physiology. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;43:3–36. doi: 10.1080/10409230701829110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dutzler R, Campbell EB, MacKinnon R. Gating the selectivity filter in ClC chloride channels. Science. 2003;300:108–112. doi: 10.1126/science.1082708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lobet S, Dutzler R. Ion-binding properties of the ClC chloride selectivity filter. Embo J. 2006;25:24–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Accardi A, Lobet S, Williams C, Miller C, Dutzler R. Synergism between halide binding and proton transport in a CLC-type exchanger. J Mol Biol. 2006;362:691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Accardi A, et al. Separate ion pathways in a Cl−/H+ exchanger. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:563–570. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguitragool W, Miller C. Uncoupling of a CLC Cl−/H+ exchange transporter by polyatomic anions. J Mol Biol. 2006;362:682–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguitragool W, Miller C. CLC Cl−/H+ transporters constrained by covalent cross-linking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20659–20665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708639104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walden M, et al. Uncoupling and turnover in a Cl−/H+ exchange transporter. J Gen Physiol. 2007;129:317–329. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jayaram H, Accardi A, Wu F, Williams C, Miller C. Ion permeation through a Cl--selective channel designed from a CLC Cl−/H+ exchanger. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804503105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ladbury JE, Doyle ML. Biocalorimetry 2 Applications of calorimetry in the biological sciences. Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiseman T, Williston S, Brandts JF, Lin LN. Rapid measurement of binding constants and heats of binding using a new titration calorimeter. Anal Biochem. 1989;179:131–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turnbull WB, Daranas AH. On the value of c: can low affinity systems be studied by isothermal titration calorimetry? J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14859–66. doi: 10.1021/ja036166s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tellinghuisen J. Isothermal titration calorimetry at very low c. Anal Biochem. 2008;373:395–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iyer R, Iverson TM, Accardi A, Miller C. A biological role for prokaryotic ClC chloride channels. Nature. 2002;419:715–718. doi: 10.1038/nature01000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Accardi A, Kolmakova-Partensky L, Williams C, Miller C. Ionic currents mediated by a prokaryotic homologue of CLC Cl− channels. J Gen Physiol. 2004;123:109–119. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim HH, Miller C. Intracellular proton-transfer mutants in a CLC Cl−/H+ exchanger. J Gen Physiol. 2009;133:8. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faraldo-Gomez JD, Roux B. Electrostatics of ion stabilization in a ClC chloride channel homologue from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 2004;339:981–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nimigean C, Pagel M. Ligand binding and activation in a prokaryotic cyclic nucleotide-modulated channel. J Mol Biol. 2007;371:12. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zifarelli G, Pusch M. Conversion of the 2 Cl(−)/1 H(+) antiporter ClC-5 in a NO(3)(−)/H(+) antiporter by a single point mutation. EMBO J. 2009 doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.284. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ludewig U, Pusch M, Jentsch TJ. Two physically distinct pores in the dimeric ClC-0 chloride channel. Nature. 1996;383:340–343. doi: 10.1038/383340a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pusch M, Ludewig U, Rehfeldt A, Jentsch TJ. Gating of the voltage-dependent chloride channel CIC-0 by the permeant anion. Nature. 1995;373:527–531. doi: 10.1038/373527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen TY, Miller C. Nonequilibrium gating and voltage dependence of the ClC-0 Cl− channel. J Gen Physiol. 1996;108:237–250. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.4.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Traverso S, Elia L, Pusch M. Gating competence of constitutively open CLC-0 mutants revealed by the interaction with a small organic Inhibitor. J Gen Physiol. 2003;122:295–306. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller C, Nguitragool W. A provisional transport mechanism for a chloride channel-type Cl−/H+ exchanger. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogawa H, Toyoshima C. Homology modeling of the cation binding sites of Na+K+-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202622299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma H, Inesi G, Toyoshima C. Substrate-induced conformational fit and headpiece closure in the Ca2+ATPase (SERCA) J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304120200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inesi G, MH, Hua S, Toyoshima C. Characterization of Ca2+ ATPase residues involved in substrate and cation binding. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;986(8) doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toyoshima C, Nomura H, Sugita Y. Crystal structures of Ca2+-ATPase in various physiological states. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;986:8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matulef K, Maduke M. Side-dependent inhibition of a prokaryotic ClC by DIDS. Biophys J. 2005;89:1721–1730. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.066522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zdebik AA, et al. Determinants of anion-proton coupling in mammalian endosomal CLC proteins. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4219–4227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708368200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richard H, Foster J. Escherichia coli glutamate- and arginine-dependent acid resistance systems increase internal pH and reverse transmembrane potential. J Bacteriol. 2004;186 doi: 10.1128/JB.186.18.6032-6041.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gut H, et al. Escherichia coli acid resistance: pH-sensing, activation by chloride and autoinhibition in GadB. EMBO J. 2006;25 doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ludewig U, Jentsch TJ, Pusch M. Analysis of a protein region involved in permeation and gating of the voltage-gated Torpedo chloride channel ClC-0. J Physiol. 1997;498:691–702. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rychkov G, Pusch M, Roberts M, Bretag A. Interaction of hydrophobic anions with the rat skeletal muscle chloride channel ClC-1: effects on permeation and gating. J Physiol. 2001;530:379–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0379k.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pusch M, Jordt SE, Stein V, Jentsch TJ. Chloride dependence of hyperpolarization-activated chloride channel gates. J Physiol. 1999;515:341–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.341ac.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bergsdorf EY, Zdebik AA, Jentsch TJ. Residues important for nitrate/proton coupling in plant and mammalian CLC transporters. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901170200. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zifarelli G, Murgia AR, Soliani P, Pusch M. Intracellular proton regulation of ClC-0. J Gen Physiol. 2008 doi: 10.1085/jgp.200809999. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Engh AM, Faraldo-Gomez JD, Maduke M. The mechanism of fast-gate opening in ClC-0. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:335–349. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.