Abstract

Protocols to effect β-arylation of sp3 C–H bonds via Pd(II)/(IV) and Pd(0)/(II) catalytic cycles have been achieved using a newly developed monodentate CONHC6F5 directing group. These reactions provide an unprecedented means to functionalize sp3 C–H bonds in aliphatic carboxylic acid–derived substrates.

Keywords: Amide, palladium, arylation, sp3 C, H activation

1. Introduction

Pd–catalyzed C–H activation/functionalization reactions have emerged as powerful synthetic tools for converting ubiquitous sp2 and sp3 C–H bonds into desired chemical functional groups.1 Methods for effecting the functionalization of aryl and heretoaryl sp2 C–H bonds have been extensively investigated and have found impressive applications in natural products synthesis and drug discovery.2 In contrast, the functionalization of more inert sp3 C–H bonds still represents a tremendous challenge in organic synthesis and remains at an early stage of development.

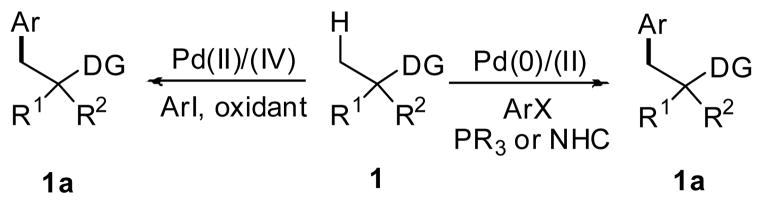

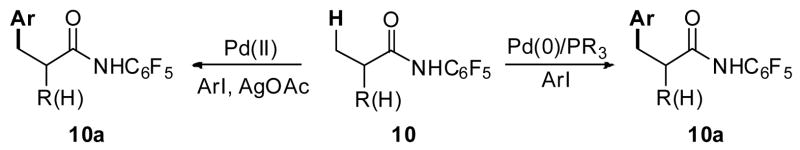

The majority of sp3 C–H activation methods utilize heteroatom-containing functional groups that can coordinate the metal and direct C–H insertion.3 Indeed, reactions that proceed via cleavage of sp3 C–H bonds directed by heteroatom-directing groups such as oximes,4 oxazolines,5 and pyridines6 have been well-documented. Recent investigations in the area of directed C–H functionalization focus on utilizing more synthetically practical functional groups, such as amino,7 amide8 and carboxyl9 groups as directing groups. Using the directing group approach, a number of sp3 C-H activation/C-C bond forming reactions have been reported.2 One important class of these reactions concerns the Pd-catalyzed arylation of unactivated sp3 C-H bonds with aryl halides which was developed via two distinct catalytic pathways: Pd(II)/(IV) catalysis which uses aryl iodides and requires external oxidant for reoxidation, and Pd(0)/(II) homogeneous catalysis which accommodates organophosphine or NHC ligands and aryl halides (Scheme 1).1,2

Scheme 1.

Two catalytic cycles to effect Pd-mediated arylation of sp3 C–H bonds.

The redox chemistry involving Pd(IV) has been poorly understood in its early stage and gained much attention in recent years.10 A number of reactions have been developed using the Pd(II)/(IV) catalysis which includes acetoxylation, amination, arylation, halogenation, among others.1,2 For instance, Chen reported an interesting arylation of aldehydic C-H bonds with [Ph2I]Br which could involve the Pd(II)/(IV) catalysis.11 Sanford and Daugulis independently developed general approaches using directed C-H activation and [Ph2I]PF612 or [Ph2I]BF46d for arylation of sp2 C–H bonds. Building on these studies, Daugulis et al. went on to develop a highly efficient C–H arylation reaction using readily available aryl iodides and applied these conditions to effect arylation of sp3 C–H bonds (Scheme 2).6b, 6c Notably, despite numerous evidence for Pd(II)/Pd(IV) catalysis reported in literature,1–4 the involvement of Pd(II)/Pd(III) catalysis has also been invoked with substantial experimental support.13 It is possible the competition between these two catatlytic pathways may vary with substrates.

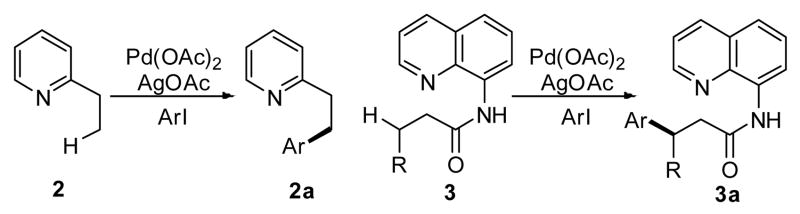

Scheme 2.

Arylation of sp3 C–H bonds using aryl iodides.

Their initial reports described the arylation of an sp3 C–H bond in 2-ethylpyridine (2) using catalytic amounts of Pd(OAc)2 and stoichiometric AgOAc.6b A subsequent report by the same group demonstrated impressive examples of β-arylation using an effective bisdentate directing group such as 3).6c Notably, this reaction represents a rare example of catalytic methylene C–H activation in Pd chemsitry. Corey el al. have used this directing group and these reaction conditions to functionalize sp3 C–H bonds in natural amino acid derivatives (4) (Scheme 3).14 A related investigation by our group described β-arylation of simple aliphatic acids without installing a directing group (5); however the yields were low (40–70%) and the reaction temperature was higher (130 °C).9b We found, by converting the carboxylic acids into structurally analogous hydroxamic acids (6), the yields could be greatly improved (>80 %), and the reaction could be carried out at lower temperature (60 °C).15 However, substrates containing α-hydrogens were not reactive with either carboxylic acids or this directing group.

Scheme 3.

Pd(II)/Pd(IV) catalysis for sp3 C–H arylation.

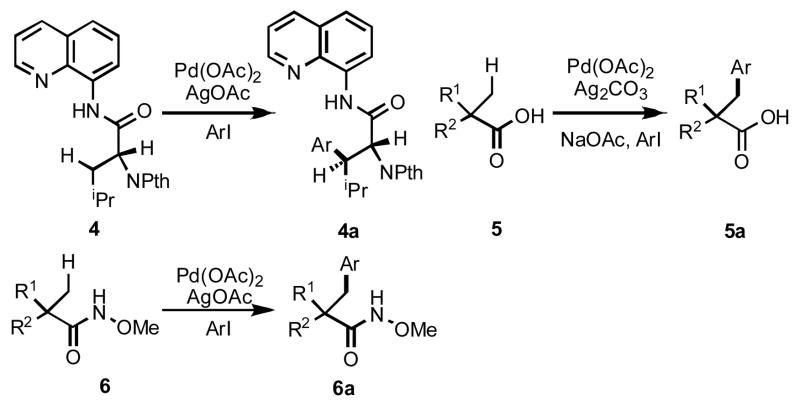

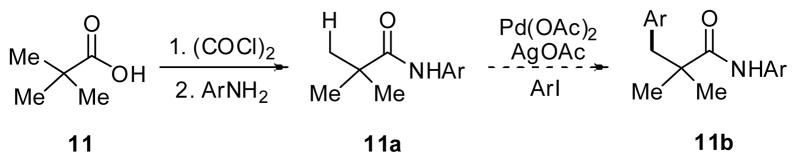

Pd(0)-catalyzed arylation of C–H bonds using phosphine or NHC ligands and aryl halides represents another class of C–H activation/arylation reactions that has been extensively studied in recent decades.16–18 Compared to the aforementioned Pd(II)/Pd(IV) C–H arylation reactions, this mode of catalysis does not require stoichiometric silver salts, which is a significant practical advantage. Both intra- and intermolecular arylation of aryl and heteroaryl sp2 C–H bonds has proven to be highly successful.16–18 On the other hand, only a limited number of sp3 C–H arylation reactions via Pd(0)/Pd(II) catalysis have been achieved to date (Scheme 4).19 In this manuscript, we describe Pd-catalyzed sp3 C–H arylation protocols using a recently developed amide directing group and two modes of catalysis, Pd(0)/(II) and Pd(II)/(IV). (Scheme 5). Notably, the use of this particular directing group allowed for a significant expansion in substrate scope such that carboxylic acid derivatives containing α-hydrogen atoms could be tolerated.

Scheme 4.

Arylation of sp3 C–H bonds via Pd(0)/(II) catalysis.

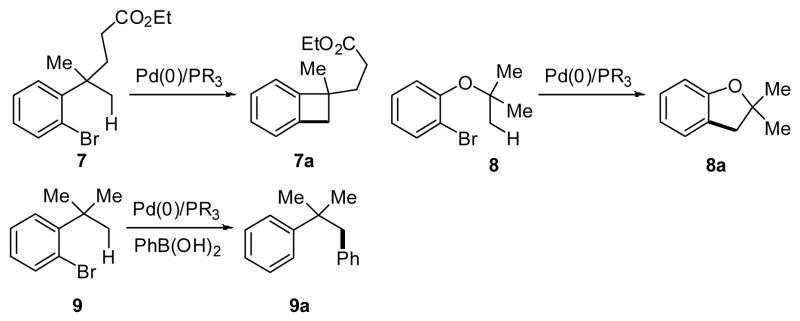

Scheme 5.

Amide-directed arylation of sp3 C–H bonds via two modes of catalysis.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Arylation of sp3 C–H bonds via Pd(II)/(IV) catalysis

In 2007, we reported that the β-methyl groups of aliphatic carboxylic acids could be cross-coupled with aryl iodides via sp3 C–H bond activation in the presence of stoichiometric Ag2CO3 (Scheme 3).9b However, the carboxylate moiety proved to be a poor directing group for activation of inert sp3 C–H bonds, as it required high reaction temperatures and gave low yields. Additionally, we found that this reaction was incompatible with aliphatic carboxylic acids that contained α-hydrogen atoms, a problem that could not be remedied by converting the carboxylate to other directing groups, such as oxazoline5 or hydroxamic acid (6).8d Thus, the substrate scope was limited to compounds that contained quaternary α-carbon atoms. In an effort to overcome both of these issues, we sought to develop a novel directing group that would enhance the reactivity and broaden the substrate scope.

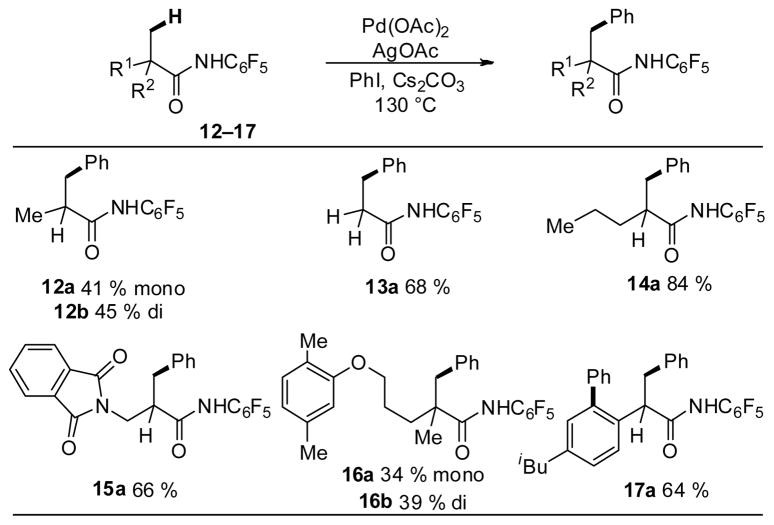

Based on previous reports, we were aware that bis-coordinating pyridine-containing directing groups such as 3 and 4 were capable of directing C–H activation with substrates that contained α-hydrogen atoms.6c, 14 However, we thought that a simpler monodentate directing group could provide both the reactivity and α-hydrogen tolerance that we sought. Based on the high reactivity observed with hydroxamic acids (6),8d we hypothesized that replacing the methoxy group with functional group in which the steric and electronic properties could be readily adjusted could prove to be highly useful in developing an improved directing group. Given that a wide variety of substituted anilines are commercially available, we identified N-aryl amides as a class of potential directing groups that would be easily tunable. To test this idea, we initially converted pivalic acid into several N-arylpivalamides to examine whether the amide group was capable of directing C–H activation (Scheme 6 and Table 1).

Scheme 6.

Preparation of amide substrates.

Table 1.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ar | base | yield (%) | |||

| sm | mono | di | tri | |||

| 1 | Ph | none | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 |  |

Cs2CO3 | 91 | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | Cs2CO3 | 39 | 41 | 12 | 8 | |

| 4 |  |

none | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | Cs2CO3 | 12 | 32 | 40 | 16 | |

Reaction conditions: 0.2 mmol substrate, 10 mol% Pd(OAc)2, 4 equiv AgOAc, 1.2 equiv Cs2CO3, 0.5 mL iodobenzene, 130°C,3 h, air.

Yield was determined by 1H NMR analysis of crude product using CH2Br2 as the internal standard.

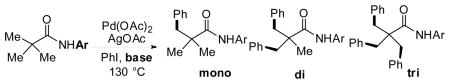

We were encouraged by the initial observation of trace amount of the desired arylation products using simple aniline-derived amide with Cs2CO3 in neat PhI (Table 1, entry 2). Further screening revealed that electron-withdrawing, fluorine-substituted directing groups showed dramatically higher reactivity (Table 1, entries 3 and 5). The addition of base was found to be crucial for the arylation reaction (as no product was obtained in absence of base) (Table 1, entries 1 and 4) with Cs2CO3 giving the highest yield.

To test if the reaction would be compatible with substrates containing α-hydrogen atoms, we converted isobutyric acid to an array of different N-arylisobutyramides. Gratifyingly, we obtained a mixture of mono- and di-arylation products in high yields. The reaction was optimized using various directing groups. Among those screened, CONHC6F5 gave the best results (Table 2).

Table 2.

Screening of directing groups for α-hydrogen-containing substrates a

|

The reaction conditions are identical to those described in Table 1.

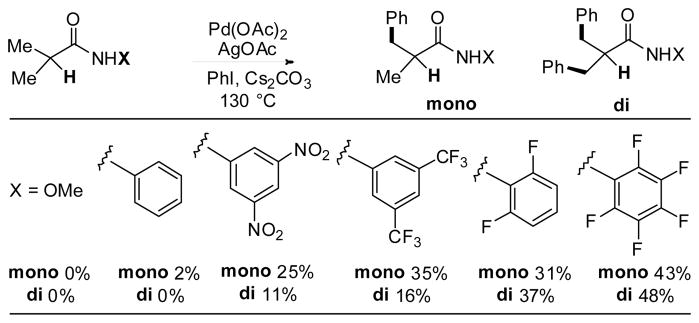

A variety of carboxylic acid derivatives were arylated in reasonable to excellent yields under the optimized reaction conditions (Table 3). β-Amino acid substrate 15, as well as substrates derived from commercial drugs, such as 16 (from Gemfibrozil) and 17 (from Ibuprofen), were also compatible. For substrate 17, both β-arylation of the methyl group and γ-arylation of the arene were observed in the major product. For substrate 14, it was possible to reduce the reaction temperature to 100 °C, though the yield decreased to 64 % even after 12 h.

Table 3.

|

The reaction conditions are identical to those described in Table 1.

Isolated yield.

2.2. Arylation of sp3 C–H bonds via Pd(0)/(II) catalysis

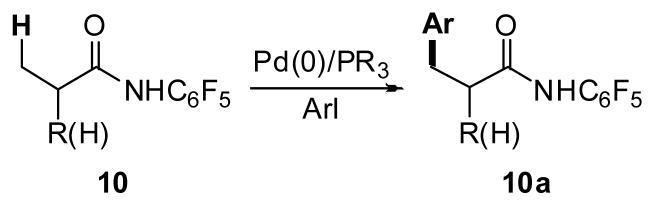

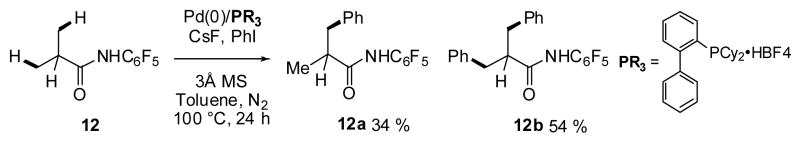

Despite the remarkable efficiency of these Pd(II)/(IV)-catalyzed arylation reactions, the need for superstoichiometric amount of AgOAc is a major drawback. In contrast, Pd(0)-catalyzed homogeneous reactions accommodates phosphine or NHC ligands and do not require a co-oxidants or silver salts, which are significant practical advantages. Miura and Daugulis have previously reported pioneering examples of Pd(0)/PR3-catalyzed sp2 C–H arylation reactions directed by amides18a and carboxylic acids, 18c respectively. We have recently reported CONHC6F5-directed arylation of sp3 C–H bonds (Scheme 7).8f This work will be summarized briefly here to allow for comparison to our Pd(II)/(IV) C–H arylation data, as both reactions rely upon the same directing group.

Scheme 7.

Pd(0)/PR3-catalyzed arylation of sp3 C–H bonds.

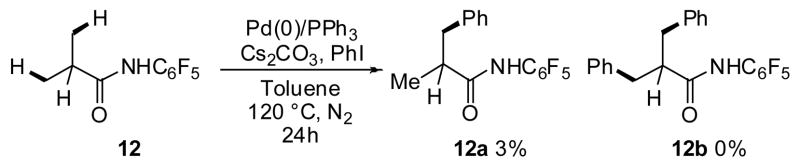

Based on the successful development of Pd(II)/(IV)-catalyzed arylation directed by CONHC6F5 group, we initiated our investigation of Pd(0)-catalyzed activation of sp3 C–H bonds. Our initial experiment using substrate 12 gave trace quantities of the desired mono-arylated product with PPh3 as the ligand and Cs2CO3 as the base (Scheme 8). To improve this result, systematic screening of ligands, bases, solvents and coupling partners was undertaken.

Scheme 8.

Initial experiments with Pd(0)/PR3-catalyzed sp3 C–H arylation.

Among the bases tested, only CsF gave appreciable amounts of the desired product. Buchwald ligands, protected as HBF4 salts using Fu’s strategy,20 were found to give considerably better yield than PPh3. To our surprise, the reaction was only found to proceed when aryl iodides were used; aryl bromides, chlorides, triflates, and tosylates did not give any of the desired product. The oxidative insertion of Pd(0) into an aryl-halide bond is the most facile for aryl iodides. However, Fagnou and others have established that the use of aryl iodides typically results in poor reactivity due to the accumulation of iodide anions in reaction mixture, which ultimately leads to catalyst poisoning.21 Indeed, higher catalyst and ligand loadings (10 and 20 mol%, respectively) were needed to obtain high product yields, which could be attributed to the poisoning phenomenon. With the optimized conditions in hand, we obtained 12a in 34% and 12b in 54% yield (Scheme 9).

Scheme 9.

Optimized conditions.

Through the development of sp3 C–H arylation protocols via Pd(0)/(II) and Pd(II)/(IV) catalysis, we learned there are inherent advantages and disadvantages of both catalytic cycles. C–H arylation reactions via Pd(II)/(IV) catalysis went to completion in shorter reaction times (<3h) and gave generally higher product yields than did Pd(0)/(II) catalysis for the same set of substrates. Nevertheless, Pd(0)/(II)-catalyzed C–H arylation was found to proceed under milder reaction conditions and did not require stoichiometric silver salts, though the current conditions did require higher catalyst and ligand loadings due to potential catalyst poisoning. Further optimization is currently underway for the Pd(0)/(II) reaction, in an effort to utilize other aryl halides in order to suppress catalyst poisioning.

3. Conclusions

β-Arylation of inert sp3 C–H bonds via two catalytic pathways has been achieved using a newly developed monodentate amide directing group. These studies have allowed for the discovery of an unprecedented C–H activation reaction of carboxylic acid–derived substrates that contain α-hydrogen atoms. Follow-up studies to further tune the directing group and to develop asymmetric sp3 C–H arylation of gem-dimethyl groups using chiral phosphine ligands are underway in our laboratory.

Experimental

3.1. General experimental

Solvents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and used directly without further purification. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian instrument (400 MHz and 100 MHz, respectively) and internally referenced to the SiMe4 signal. Exact mass spectra for new compounds were recorded on a VG 7070 high resolution mass spectrometer. Analytical GC-MS was performed on a Hewlett-Packard G1800C instrument connected to an electron ionization detector using a MS-5 GC column (30 × 0.25 mm). Infrared spectra were recorded on a Perkin Elmer FT-IR Spectrometer.

Carboxylic acids, anilines and phosphine ligands were purchased from Aldrich, Acros and Strem and were used as received without further purification. Pd(OAc)2 was received from Alfa Aesar.

3.2. Preparation of amide substrates

An acid chloride (20 mmol), prepared from the corresponding carboxylic acid and oxalyl chloride, was added to a vigorously stirred solution of 2,3,4,5,6-pentafluoroaniline (22 mmol) in toluene (50 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 h under reflux, and then stirred at room temperature for 4 h. The product mixture was concentrated under vacuum and was recrystallized from ethyl acetate/hexane (100 °C to 0 °C) to give the amide.

3.3. General procedure for palladium-catalysed arylation of sp3 C-H bonds via Pd(II)/(IV) catalysis

Substrate (0.2 mmol), aryl iodide (0.5 mL), AgOAc (0.8 mmol), and Cs2CO3 (0.24 mmol) were added in a 25 mL glass pressure vessel. Pd(OAc)2 (0.02 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture, tightly capped and heated to 130 °C with vigorous stirring. The reaction was stopped after it completely turned black (typically 3h). The black solid was filtered off, and the solvent was removed in a rotary evaporator. The purification was done by silica gel column chromatography using 1–5% diethyl ether/hexane as an eluting solvent.

3.3.1. 2-methyl-N-(perfluorophenyl)-3-phenylpropanamide (12a)

Substrate 12 was arylated following the general procedure. After purification by column chromatography, 12a was obtained as a colorless solid (27.1 mg, 41 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.34-7.10 (m, 5H), 6.72 (bs, 1H), 3.10-2.97 (m, 1H), 2.83-2.71 (m, 2H), 1.31 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 174.7, 139.3, 129.2, 129.0, 127.0, 44.1, 40.7, 18.1; IR (neat) ν 3256, 2927, 1682, 1498 cm−1; HRMS (ESI-TOF) Calcd for C16H12F5NO (MH+): 330.0912; found: 330.0907.

3.3.2. 2-benzyl-N-(perfluorophenyl)-3-phenylpropanamide (12b)

Substrate 12 was arylated following the general procedure. After purification by column chromatography, 12b was obtained as a colorless solid (36.6 mg, 45 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.32-7.20 (m, 8H), 6.12 (bs, 1H), 3.12-3.05 (m, 2H), 2.95-2.79 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.2, 139.2, 129.2, 129.0, 127.1, 53.4, 39.5; IR (neat) ν 3231, 2919, 1674, 1526, 1450 cm−1; HRMS (ESI-TOF) Calcd for C22H16F5NO (MH+): 406.1225; found: 406.1235.

3.3.3. N-(perfluorophenyl)-3-phenylpropanamide (13a)

Substrate 13 was arylated following the general procedure. After purification by column chromatography, 13a was obtained as a colorless solid (43.0 mg, 68 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.32-7.20 (m, 4H), 6.89 (bs, 1H), 3.05 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 2.75 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.1, 143.3, 129.0, 128.6, 126.9, 38.3, 31.6; IR (neat) ν 3264, 2921, 1680, 1530, 1495 cm−1; HRMS (ESI-TOF) Calcd for C15H10F5NO (MH+): 316.0755; found: 316.0755.

3.3.4. 2-benzyl-N-(perfluorophenyl)pentanamide (14a)

Substrate 14 was arylated following the general procedure. After purification by column chromatography, 14a was obtained as a colorless solid (62.3 mg, 84 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.39-7.15 (m, 4H), 6.49 (bs, 1H), 2.95-2.82 (m, 1H), 2.82-2.80 (m, 1H), 2.61-2.54 (m, 1H), 2.04-1.99 (m, 1H), 1.88-1.68 (m, 1H), 1.53-1.32 (m, 4H), 0.93 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 176.6, 139.5, 129.1, 129.0, 126.9, 105.1, 44.2, 39.7, 36.2, 33.1, 23.0, 14.25; IR (neat) ν 3274, 2901, 1650, 1520 cm−1; HRMS (ESI-TOF) Calcd for C19H18F5NO (MH+): 371.1309; found: 371.1310.

3.3.5. 2-benzyl-3-(1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)-N-(perfluorophenyl)propanamide (15a)

Substrate 15 was arylated following the general procedure. After purification by column chromatography, 15a was obtained as a colorless solid (62.7 mg, 66 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.86-7.73 (m, 4H), 7.30-7.16 (m, 4H), 6.74 (bs, 1H), 4.18-4.13 (m, 1H), 3.92-3.86 (m, 1H), 3.51-3.39 (m, 1H), 3.15-3.09 (m, 1H), 2.96-2.91 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.2, 168.6, 138.1, 134.6, 134.6, 129.1, 127.2, 123.8, 48.1, 40.6, 37.2; IR (neat) ν 3268, 2918, 2850, 1716, 1522, 1495 cm−1; HRMS (ESI-TOF) Calcd for C24H15F5N2O (MH+): 475.1076; found: 475.1075.

3.3.6. 2-benzyl-6-(2,5-dimethylphenyl)-2-methyl-N-(perfluorophenyl)hexanamide (16a)

Substrate 16 was arylated following the general procedure. After purification by column chromatography, 16a was obtained as a colorless solid (33.5 mg, 34 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.42 (s, 1H), 7.30-7.24 (m, 5H), 6.98 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.77 (s, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 3.99 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H), 3.16 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 2H), 2.80 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 2H), 2.80 (s, 3H), 2.10 (s, 3H) 1.98-1.40 (m, 6H), 1.30 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 175.4, 157.0, 137.1, 137.0, 130.7, 130.6, 127.2, 123.8, 121.3, 112.5, 92.6, 68.0, 48.3, 46.7, 36.6, 25.1, 21.5, 16.1 cm−1; IR (neat) ν 3296, 2924, 2869, 1675, 1523, 1490 cm−1; HRMS (ESI-TOF) Calcd for C27H26F5NO2 (MH+): 492.1956; found: 492.1959.

3.3.7. 2,2-dibenzyl-6-(2,5-dimethylphenyl)-N-(perfluorophenyl)hexanamide (16b)

Substrate 16 was arylated following the general procedure. After purification by column chromatography, 16b was obtained as a colorless solid (44.3 mg, 39 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.30-7.21 (m, 10H), 6.93 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.76-6.59 (m, 3H), 4.00 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 3.27 (d, J = 13.6 Hz, 2H), 2.94 (d, J = 13.6 Hz, 2H), 2.28 (s, 3H), 2.20-2.08 (m, 2H), 1.96 (s, 3H), 1.87-1.77 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 174.6, 156.8, 137.0, 137.0, 130.6, 130.6, 128.7, 127.2, 123.7, 121.5, 112.4, 105.1, 67.8, 42.9, 30.1, 28.5, 21.7, 16.1; IR (neat) ν 3299, 2924, 2856, 1676, 1523, 1453 cm−1; HRMS (ESI-TOF) Calcd for C33H30F5NO2 (MH+): 568.2269; found: 568.2269.

3.3.8. 2-(5-isobutylbiphenyl-2-yl)-N-(perfluorophenyl)-3-phenylpropanamide (17a)

Substrate 17 was arylated following the general procedure. After purification by column chromatography, 17a was obtained as a colorless solid (67.0 mg, 64 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.59-7.16 (m, 9H), 6.99-6.93 (m, 4H), 6.28 (s, 1H), 3.97 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 3.49-3.45 (m, 1H), 3.06-3.03 (m, 1H), 2.47 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.90-1.85 (m, 1H), 0.93 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.1, 142.5, 141.4, 141.4, 139.4, 133.4, 131.2, 129.6, 129.5, 129.4, 128.8, 128.6, 127.8, 127.6, 126.7, 50.7, 45.3, 39.8, 30.5, 22.7; IR (neat) ν 3260, 2950, 2929, 1700, 1512, 1489, 1411 cm−1; HRMS (ESI-TOF) Calcd for C31H26F5NO (MH+): 523.1945; found: 523.1944.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge The Scripps Research Institute, the National Institutes of Health (NIGMS, 1 R01 GM084019-02), Amgen and Eli Lilly for financial support. We thank the A. P. Sloan Foundation for a fellowship (J.-Q.Y.), and the Bristol Myers Squibb for graduate fellowships (M. W.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.For reviews, see; Yu JQ, Giri R, Chen X. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;4:4041. doi: 10.1039/b611094k.Dick AR, Sanford MS. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:2439.Daugulis O, Zaitsev VG, Shabashov D, Pham QN, Lazareva A. Synlett. 2006:3382.Alberico D, Scott ME, Lautens M. Chem Rev. 2007;107:174. doi: 10.1021/cr0509760.Chen X, Engle KM, Wang DH, Yu JQ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:5094. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806273.

- 2.For reviews, see; Hassan J, Sévignon M, Gozzi C, Shultz E, Lemaire M. Chem Rev. 2002;102:1359. doi: 10.1021/cr000664r.Kakiuchi F, Murai S. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:826. doi: 10.1021/ar960318p.Campeau L-C, Fagnou K. Chem Commun. 2006:1253. doi: 10.1039/b515481m.Alberico D, Scott ME, Lautens M. Chem Rev. 2007;107:174. doi: 10.1021/cr0509760.Seregin IV, Gevorgyan V. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36:1173. doi: 10.1039/b606984n.Kakiuchi F, Kochi T. Synthesis. 2008:3013.

- 3.(a) Ryabov AD. Chem Rev. 1990;90:403. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yu JQ, Giri R, Chen X. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;4:4041. doi: 10.1039/b611094k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ackermann L. Top Organomet Chem. 2007;24:35. [Google Scholar]; (d) Kalyani D, Sanford MS. Top Organomet Chem. 2007;24:85. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Desai LV, Hull KL, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9542. doi: 10.1021/ja046831c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Thu HY, Yu WY, Che CM. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9048. doi: 10.1021/ja062856v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Desai LV, Malik HA, Sanford MS. Org Lett. 2006;8:1141. doi: 10.1021/ol0530272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Giri R, Liang J, Lei JG, Li JJ, Wang DH, Chen X, Naggar IC, Guo C, Foxman BM, Yu JQ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:7420. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Giri R, Chen X, Hao XS, Li JJ, Liang J, Fan ZP, Yu JQ. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2005;16:3502. [Google Scholar]; (c) Giri R, Chen X, Yu JQ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:2112. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Giri R, Wasa M, Breazzano SP, Yu JQ. Org Lett. 2006;8:5685. doi: 10.1021/ol0618858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Chen X, Li JJ, Hao XS, Goodhue CE, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:78. doi: 10.1021/ja0570943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Kalyani D, Sanford MS. Org Lett. 2005;7:4149. doi: 10.1021/ol051486x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shabashov D, Daugulis O. Org Lett. 2005;7:3657. doi: 10.1021/ol051255q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zaitsev VG, Shabashov D, Daugulis O. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:13154. doi: 10.1021/ja054549f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kalyani D, Deprez NR, Desai LV, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:7330. doi: 10.1021/ja051402f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Chen X, Goodhue CE, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12634. doi: 10.1021/ja0646747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Hull KL, Lanni EL, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14047. doi: 10.1021/ja065718e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Hull KL, Anani WQ, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7134. doi: 10.1021/ja061943k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazareva A, Daugulis O. Org Lett. 2006;8:5211. doi: 10.1021/ol061919b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Zaitsev VG, Daugulis O. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4156. doi: 10.1021/ja050366h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang S, Li B, Wan X, Shi Z. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6066. doi: 10.1021/ja070767s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shabashov D, Daugulis O. J Org Chem. 2007;72:7720. doi: 10.1021/jo701387m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wang DH, Wasa M, Giri R, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:7190. doi: 10.1021/ja801355s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Wasa M, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14058. doi: 10.1021/ja807129e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wasa M, Engle KM, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9886. doi: 10.1021/ja903573p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Miura M, Tsuda T, Satoh T, Pivsa-Art S, Nomura M. J Org Chem. 1998;63:5211. [Google Scholar]; (b) Giri R, Maugel N, Li JJ, Wang DH, Breazzano SP, Saunders LB, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3510. doi: 10.1021/ja0701614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chiong HA, Pham QN, Daugulis O. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9879. doi: 10.1021/ja071845e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Giri R, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008:130, 14082. doi: 10.1021/ja8063827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Wang DH, Mei TS, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:17676. doi: 10.1021/ja806681z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Zhang YH, Shi BF, Yu JQ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:6097. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Zhang YH, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:14654. doi: 10.1021/ja907198n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Wang D-H, Engle KM, Shi B-F, Yu J-Q. Science. 2009 ASAP. [Google Scholar]; (i) Shi B-F, Zhang Y-H, Lam JK, Wang D-H, Yu J-Q. J Am Chem Soc. 2009 doi: 10.1021/ja909571z. ASAP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.For early proposal of formation of Pt(IV) complexes, see: Pope WJ, Peachy S. J Proc Chem Soc London. 1907;23:86.For oxidation of Pt(II) to Pt(IV) by O2 see: Rostovtsev VV, Henling LM, Labinger JA, Bercaw JE. Inorg Chem. 2002;41:3608. doi: 10.1021/ic0112903.Uson R, Fornies J, Navarro R. J Organomet Chem. 1975;96:307.Trost BM, Tanoury GJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:4753.Canty AJ. Acc Chem Res. 1992;25:83.

- 11.Xia M, Chen ZC. Syn Commun. 2000;30:531. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daugulis O, Zaitsev VG. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:4046. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) McAuley A, Whitcombe TW. Inorg Chem. 1988;27:3090. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hull KL, Anani WQ, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7134. doi: 10.1021/ja061943k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cotton FA, Koshevoy IO, Lahuerta P, Murillo CA, Sanaú M, Ubeda MA, Zhao QL. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:13674. doi: 10.1021/ja0656595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kaspi AW, Yahav-Levi A, Goldberg I, Vigalok A. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:5. doi: 10.1021/ic701722f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Furuya T, Ritter T. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10060. doi: 10.1021/ja803187x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Mei TS, Wang X, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:10806. doi: 10.1021/ja904709b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reddy BVS, Reddy LR, Corey EJ. Org Lett. 2006;8:3391. doi: 10.1021/ol061389j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unpublished results..

- 16.For arylation of heterocycles see: Nakamura N, Tajima Y, Sakai K. Heterocycles. 1982;17:235.Akita Y, Ohta A. Heterocycles. 1982;19:329.Pivsa-Art S, Satoh T, Kawamura Y, Miura M, Nomura M. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1998;71:467.Park CH, Ryabova V, Seregin IV, Sromek AW, Gevorgyan V. Org Lett. 2004;6:1159. doi: 10.1021/ol049866q.

- 17.For pioneering work on Pd(0)-catalyzed arylation of arenes see: Hennings DD, Iwasa S, Rawal VH. J Org Chem. 1997;62:2. doi: 10.1021/jo961876k.Satoh T, Kawamura Y, Miura M, Nomura M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1997;36:1740.

- 18.For Pd(0)-catalyzed intermolecular arylation of sp2 C–H bonds see: Kametani Y, Satoh T, Miura M, Nomura M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:2655.Lafrance M, Fagnou K. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:16496. doi: 10.1021/ja067144j.Chiong HA, Pham Q-N, Daugulis O. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9879. doi: 10.1021/ja071845e.

- 19.(a) Dyker G. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1992;31:1023. [Google Scholar]; (b) Baudoin O, Herrbach A, Guéritte F. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:5736. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhao J, Campo M, Larock RC. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:1873. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Barder TE, Walker SD, Martinelli JR, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4685. doi: 10.1021/ja042491j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lafrance M, Gorelsky SI, Fagnou K. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14570. doi: 10.1021/ja076588s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Netherton MR, Fu GC. Org Lett. 2001;3:4295. doi: 10.1021/ol016971g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campeau LC, Parisien M, Jean A, Fagnou K. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:581. doi: 10.1021/ja055819x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]