Summary

Bacillus subtilis spores are encased in a protein assembly called the spore coat that is made up of at least 70 different proteins. Conventional electron microscopy shows the coat to be organized into two distinct layers. Because the coat is about as wide as the theoretical limit of light microscopy, quantitatively measuring the localization of individual coat proteins within the coat is challenging. We used fusions of coat proteins to GFP to map genetic dependencies for coat assembly and define three independent sub-networks of coat proteins. To complement the genetic data, we measured coat protein localization at sub-pixel resolution and integrated these two data sets to produce a distance-weighted genetic interaction map. Using these data we predict that the coat comprises at least four spatially distinct layers, including a previously uncharacterized glycoprotein outermost layer that we name the spore crust. We found that crust assembly depends on proteins we predicted to localize to the crust. The crust may be conserved in all Bacillus spores and may play critical functions in the environment.

Results and Discussion

The integration of complementary data types has been important in elucidating the structural organization of multi-protein assemblies with sizes that are near the theoretical limit of resolution of light microscopy [1]. Data integration has produced high-resolution models of the yeast nuclear pore complex, the kinetochore and clathrin-coated vesicles [2–4]. Using the protein visualization tools of cell biology and light microscopy, it is a relatively simple matter, even in bacterial cells [5], to investigate the subcellular localization of individual proteins to various structures, such as the flagellum [6], the divisome [7] or the genetic transformation machinery [8]. Gaining additional information about the arrangement of individual proteins that appear co-localized by fluorescence light microscopy has become possible with new techniques that enable resolution far below the theoretical limit of 200 nm [9]. While very promising, these techniques are still in their infancy and, until recently, required custom-built optics systems. Although immuno-electron microscopy can convincingly localize individual proteins to specific spatial sub-regions of multi-protein assemblies [10, 11], it suffers from low sensitivity and poor structural preservation. An alternative has emerged with high-resolution image analysis of conventional fluorescence microscopy images [4, 12, 13]. This approach provides resolution beyond mere co-localization of proteins without sacrificing the advantages of working with live cells. Here we describe a novel integrated approach to identify the architecture of a large multi-protein structure, the spore coat of Bacillus subtilis, at an effective resolution below the theoretical limit of resolution of light microscopy.

B. subtilis can form highly resistant spores in response to adverse conditions. A division septum is placed towards one end of the sporulating cell, dividing it into two membrane-bounded compartments [14]. The smaller compartment, the forespore, becomes the spore. Two major protective structures are layered concentrically around the spherical core: the cortex (spore peptidoglycan) and the coat [15, 16]. However, some species possess an additional outermost protective layer called the exosporium [15, 17]. In B. subtilis, the coat is made up of at least 70 individual proteins synthesized in the larger mother cell compartment and deposited onto the spore surface. Thin-section transmission electron microscopy (EM) shows that the coat is organized into distinct inner and outer layers [18].

The B. subtilis Spore Coat Genetic Interaction Network

Assembly of the spore coat is controlled by a subset of coat proteins, known as the morphogenetic proteins [15, 16]. The locations of morphogenetic proteins within the coat have been inferred from a combination of genetic and electron microscopy analyses. In the spoIVA mutant, the coat fails to localize to the spore [19]. Because SpoIVA interacts directly with SpoVM, a peptide that localizes to positively-curved membrane surfaces [20], SpoIVA and SpoVM are inferred to be at the top of the genetic hierarchy. Immuno-electron microscopy shows CotE at the interface of the inner and outer layers and cotE mutant spores lack the outer coat. Thus, CotE is inferred to be in the middle of the genetic hierarchy [10, 21].

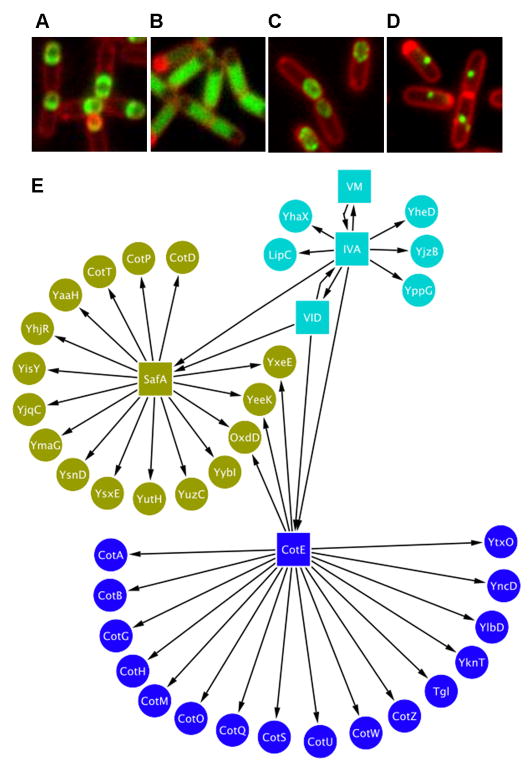

It is possible to determine genetic dependencies of individual coat proteins in deletion mutants of morphogenetic proteins using coat proteins fused to the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) [22, 23]. Using this ‘molecular epistasis’ approach we generated a genetic interaction network that incorporates 40 proteins [23, 24] (Table S1). In previous work and supplemental data (Figure S1), we identified 16 coat protein-GFP fusions to be dependent on cotE for localization and, therefore, we classified them as outer coat proteins [23].

CotE functions as an interaction hub protein for the outer coat; however, no equivalent protein has been identified for the inner coat. A strong candidate is SafA. EM analysis shows that safA mutant spores possess a defective inner coat, and immuno-gold labeling indicates that SafA resides at the cortex/inner coat interface [25, 26]. We examined the localization of our 40 coat protein-GFP fusions in the safA mutant background and identified 16 fusions that were impaired in localization (Figure 1A–D and Figure S1). Thus, it appears that SafA is the major inner coat morphogenetic protein. In total, we define three genetic interaction sub-networks within the coat (Figure 1E): the cotE-dependent outer coat, the safA-dependent inner coat, and a third group independent of cotE and safA. The proteins of this third group genetically interact solely with spoIVA and spoVM.

Figure 1. The Spore Coat Genetic Interaction Network.

Examples of fluorescence microscopy images used in construction of the network. Cells were sporulated at 37°C by suspension in Sterlini-Mandelstam medium, stained with membrane stain (FM4-64, Invitrogen, red) and imaged 3 hours after resuspension. GFP-fusion fluorescence is shown in green. (A) Cells contain yaaH fused to gfp (PE793). (B) Cells contain yaaH fused to gfp, safA is deleted (PE861); YaaH-GFP shows complete mislocalization in safA mutant cells. (C) Cells contain oxdD fused to gfp (PE634). (D) Cells contain oxdD fused to gfp, safA is deleted (PE816); OxdD-GFP shows incomplete localization in safA mutant cells, forming a single dot. (E) The spore coat interaction network was drawn in Cytoscape (www.cytoscape.org) with directional edges (arrows) denoting genetic dependencies among genes and fusion proteins. The safA-dependency data was collected in this study. The remainder of the data is shown in Figure S1. Other genetic interactions were curated from the literature (Table S1).

The B. subtilis Spore Coat High-Resolution Physical Map

The modularity of the genetic interaction network supports the idea that individual coat proteins occupy distinct spatial regions of the coat. EM observations suggest that the coat width varies between 60 nm and 250 nm [15, 16], which overlaps with the theoretical limit of resolution of light microscopy [9]. We chose to measure the spatial localization of individual coat proteins with PSICIC, an algorithm that increases effective image resolution through interpolated contouring of conventional fluorescence microscopy images [12]. We used the forespore membranes [27], as a reference for all of our measurements. All p-values quoted below are from the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

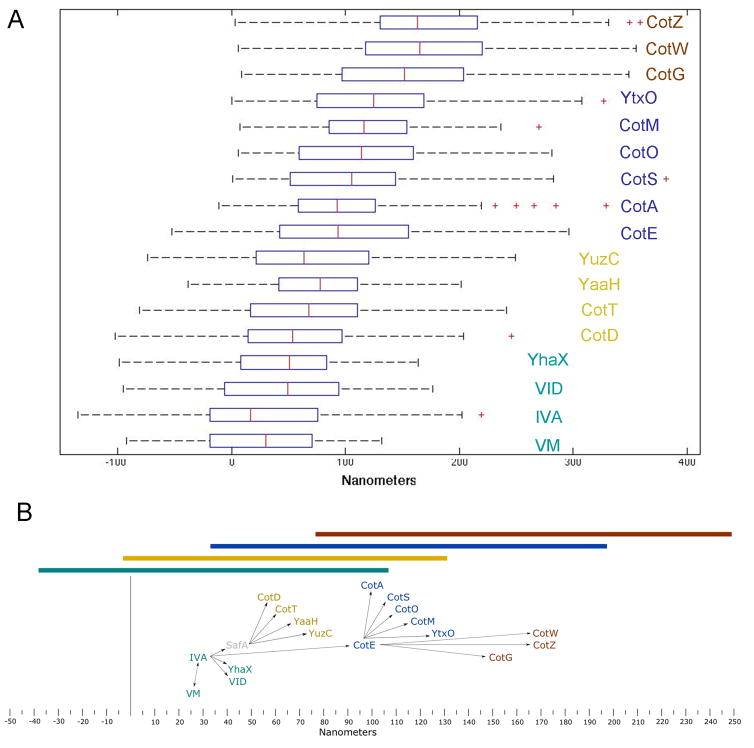

We first tested our ability to distinguish between the inner coat protein SpoVID-CFP and the outer coat protein CotE-YFP in the same cell (Figure S2). Distributions of the measurements of distances from the membrane to each of the two fusions were significantly separated (p=4.3×10−11). We extended these experiments to a set of 17 coat protein-GFP fusions representing all three genetic interaction classes (Figure 2A and Table S2). Without exception, the means of the measured distances correlated with the data from the genetic analysis. Using a significance cut-off of p ≤ 10−4 we define four spatially separated layers of proteins. Among the cotE-independent GFP-fusions, the safA-independent fusions are not significantly separated from GFP-SpoIVA (p > 0.02), while all of the safA-dependent fusions are significantly separated (7.5×10−4 < p < 4.4×10−9). These data suggest that SpoVM, SpoIVA, SpoVID and YhaX form an innermost coat layer that is spatially distinct from the safA-dependent proteins CotD, CotT, YaaH and YuzC. Wilcoxon tests against the CotE-GFP distribution suggest two spatially distinct layers within the outer coat as well. CotA, CotS, CotO, CotM and YtxO are not significantly separated (5.0×10−3 < p < 0.77). Intriguingly, CotG, CotW, and CotZ (7.7×10−7 < p < 4.7×10−10) are separated, suggesting that they are present at the outermost surface of the coat.

Figure 2. A Distance-Weighted Genetic Interaction Network.

(A) Cells were sporulated by suspension in Sterlini-Mandelstam medium in the presence of Mitotracker Red (Invitrogen). Samples were collected at hour 6, pelleted and resuspended in PBS containing 1 μg mL−1 Mitotracker Red and imaged by phase contrast and fluorescence microscopy. Five section Z-series spaced 0.3μm apart were collected. Images were taken using brightfield, phase contrast, imaging, and epifluorescence with TexasRed and FITC fluorescence filters at each z-step. Stacks were deconvolved for 30 iterations using Autoquant. The middle plane of each stack was analyzed with PSICIC to determine cell contours and to measure the location of the membranes and the fluorescent protein fusions within each cell. All strains are C-terminal GFP-fusions, except SpoIVA (GFP-SpoIVA) which is fused at the N-terminus. CotA (CotA-YFP) is a C-terminal YFP-fusion. All fusions are integrated at the endogenous locus and are expressed from the native promoter, except gfp-spoIVA and cotG-gfp, which are integrated at the amyE locus and expressed from cloned spoIVA and cotG promoters respectively. All fusions are expressed in otherwise wild type cells. Each box is delimited by the first and third quartiles and the red line crossing the box is the median. The whiskers correspond to ± 2.7 standard deviations. Crosses indicate outliers. Data and statistics are included in Table S2

(B) Network of genetic interactions with distance-weighted edges. Edges in the network diagram represent genetic interactions found in fluorescence microscopy-based molecular epistasis experiments. Text boxes contain the names of coat proteins and are centered on the mean of the measurements from the MP to the coat protein-GFP fusion at hour 6 of sporulation (Table S2) on the x-axis. The y-axis at zero nanometers represents the MP. Position along the y-axis is arbitrary. The colored bars above the diagram represent the total spread of data plus and minus one standard deviation from the means of all the members of the corresponding coat layer. The bars represent, in cyan: the safA-independent cotE-independent innermost coat layer (IVA, VM, VID, YhaX), in gold: the safA-dependent inner coat (CotD, CotT, YaaH, YuzC), in blue: the cotE-dependent outer coat (CotA, CotS, CotO, CotM, YtxO), and in brown: the cotE-dependent crust (CotG, CotW, CotZ). The diagram was drawn using Inkscape (www.inkscape.org) with an original scale of 1mm = 1nm.

We integrated our genetic interaction data with the PSICIC measurements by creating a distance-weighted interaction map (Figure 2B). From these data we propose the existence of 4 spatially distinct coat layers: 1) an innermost layer containing the cotE- and safA-independent proteins, 2) an inner coat layer containing the safA-dependent proteins, 3) the cotE-dependent outer coat and 4) a layer of cotE-dependent proteins at the outermost spore periphery. A recent study used a similar technique to suggest that the coat may be made up of more than two layers [28]. We cannot exclude the possibility that some coat proteins reside in multiple layers, particularly proteins with extended domains. It may be informative to compare the localization of proteins labeled at both termini and between structural domains to determine protein orientation [4]. Taken in total, these data suggest that the underlying genetic assumptions are correct.

The Outermost Layer of the B. subtilis Spore Coat

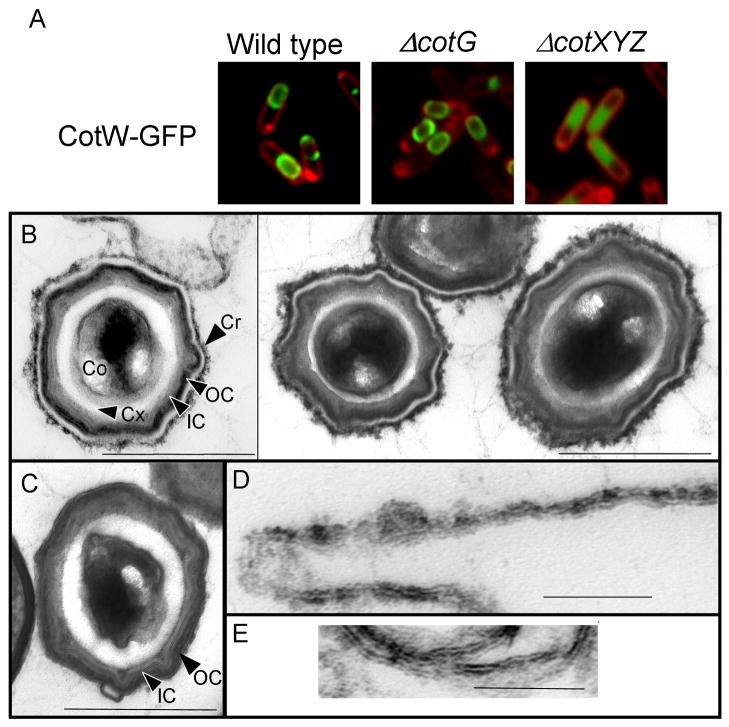

Our finding that CotG-GFP, CotW-GFP and CotZ-GFP are present in an outermost coat layer, led us to look for potential genetic interactions between these three proteins. In a mutant lacking cotXYZ, CotW-GFP completely fails to localize (Figure 3A). The mis-localization of CotW-GFP in the cotXYZ deletion and the positions of both CotW-GFP and CotZ-GFP within the outermost layer implied that cotXYZ mutant spores may have defective surfaces as also suggested by previous studies of the cotXYZ mutant [29]. The application of Ruthenium red staining to EM has recently revealed an additional outermost layer of the coat that was undetectable in conventionally-stained EMs [30]. Ruthenium red is a relatively promiscuous stain that binds sugars, free amino acids, some proteins and lipids [31] and, therefore, the composition of this surface layer remains unknown.

Figure 3. Characterization of the Outermost Coat Layer.

(A) Cells were sporulated at 37°C by suspension in Sterlini-Mandelstam medium, stained with membrane stain (FM4-64, red) and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy at hour 5. One representative field of cells is shown for each condition. The image combines signal from the TexasRed and FITC channels. All strains express cotW-gfp from the endogenous locus. From left to right: CotW-GFP in an otherwise wild type strain (PE599), CotW-GFP in a cotG::erm strain (PE2220) and CotW-GFP in a cotX cotYZ::neo strain (PE2224). (B and D) Wild type and (C and E) cotXYZ mutant spores were fixed and stained with Ruthenium red and analyzed by thin-section transmission electron microscopy. The core, cortex, inner coat, outer coat and crust are labeled (Co, Cx, IC, OC and Cr, respectively). D and E show crust layer material not associated with a spore. The size bars are 500 nm (in B and C) or 100 nm (in D and E).

We used Ruthenium Red staining to examine wild type and cotXYZ mutant spores. As previously reported, wild type spores possess an additional electron-dense layer immediately outside the outer coat that is not present in spores stained conventionally (Figure 3B and 3D), which we name the crust. A gap between this layer and the outer coat surface is readily apparent. Ruthenium red staining revealed that the crust is absent from cotXYZ spores (Figure 3C). Instead, similar structures are present as misassembled material in the milieu (Figure 3E). Therefore, CotX, CotY and/or CotZ play a morphogenetic role in the assembly of the crust around the spore. Because CotW-GFP is in the outermost layer and fails to localize in cotXYZ mutant spores, CotW is likely to be part of the crust. The simplest interpretation of these data is that the crust is comprised of protein in addition to polysaccharide. Taken together, our data suggest the existence of a glycoprotein outermost layer of B. subtilis spores that requires cotXYZ for its deposition around the spore.

Conclusions

We found a surprising amount of modularity in the genetic interaction network. It appears that most coat proteins assemble under the control of only one of the major morphogenetic proteins. As SpoIVA, SafA, CotE and CotY/CotZ have all been shown to multimerize in vitro [32–35], a possible mode of assembly for each layer may be polymerization of a basement layer made up of a morphogenetic protein and localization of other coat proteins onto that substratum

Our data also suggest a major difference between assembly of the coat and of the bacterial flagellum. Flagella are built by integrating temporal control of a transcriptional cascade with morphogenetic check-points to ensure that the basal body is assembled before the hook and filament [6], resulting in a structure that is built up component-by-component. Intuitively, a concentrically layered spherical structure such as the coat would be most easily assembled layer-by-layer from inside to outside. Among the early-expressed proteins, 3 localize to the outer coat (CotE, CotO, CotM) and 2 localize to the crust (CotW, CotZ). These data suggest a large amount of simultaneous assembly of all coat layers. We propose that coat assembly begins with the asymmetric localization of a scaffold of all 4 layers to the mother cell-proximal pole of the spore surface. This may be followed by temporally distinct waves of encasement to complete the structure [10, 24]. Also, we find that 2 late-expressed coat proteins are part of the inner coat (CotD and CotT), implying that the inner layer is accessible to molecules as large as GFP-fusion proteins until quite late in coat morphogenesis.

It is now clear that both B. subtilis and Bacillus anthracis spores have glycoprotein layers as their surfaces [30]. Variation between species in the protein and sugar components of these outermost spore-surfaces are likely to be critical in defining the ecological niches of spores and the chemical properties of the spore surface [36]. The spore crust identified here is not the equivalent of the exosporium of other spore-forming species [15, 17]. While the outermost surface of the B. anthracis spore is the exosporium, a structure equivalent to the crust may also be present. Support for this comes from a recent crystallography study identifying a layer, possibly originating from the B. anthracis coat surface [37], which has intriguing similarities to features of the B. subtilis spore surface seen in freeze-etching studies [38]. ExsY, a CotZ homolog, was found in extracts of the B. anthracis exosporium [39]. On exsY mutant spores, the exosporium assembles on the mother cell-proximal pole of the spore but fails to encase the spore [40]. It is still unknown if ExsY is a bona fide component of the exosporium or if it localizes to the surface of the coat like its B. subtilis homolog.

Similar approaches to those taken here could be used in other well-described model systems. PSICIC could be used in a similar fashion as our study to measure the location of individual proteins relative to a stationary marker. Importantly, PSICIC can also reveal the temporal dynamics of protein localization at high resolution. The approach employed here can be used to assist in ordering network connections to create models truer to the dynamics of life in three-dimensional space over time.

Experimental Procedures

Detailed experimental procedures are provided in the supplemental data. All B. subtilis strains are derivatives of PY79 [41] and are listed in Table S3. Fluorescence microscopy and sporulation by resuspension was performed as described previously [23]. Fluorescence microscopy images were analyzed using PSICIC [12]. Electron microscopy was performed according to [42].

Highlights

The B. subtilis spore coat is composed of at least 4 distinct layers.

SafA is the major organizer of the inner coat.

The spore crust is the outermost layer of the B. subtilis coat.

The cotXYZ gene cluster is necessary for crust assembly.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Related to Figure 1. Previously uncharacterized genetic interactions with cotE (A) and safA (B).

Table S1: Related to Figure 1E. Presents previously characterized genetic interactions used to construct the interaction network in Figure 1E.

Figure S2: Related to Figure 2. These data are of a proof-of-principle experiment done with dual-labeled cells, demonstrating directly that two coat proteins in the same cell are significantly separated.

Table S2: Related to Figure 2. Presents the PSICIC data in tabular form, as well as statistics.

Table S3: List of bacterial strains used in this study.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jonathan Dworkin, Adriano Henriques and Rich Losick for comments on the manuscript and strains, Anita Fernandez, David Gresham, Jake Jacobs, David Jukam, Kumaran Ramamurthi and Pranidhi Sood for critical reading of manuscript. We acknowledge the financial support of NIH grant GM081571 and Department of the Army award number W81XWH-04-1-0307 to PE, and training grant in Developmental Genetics 5T32HD007520 to PTM. The content of this material does not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the Government and no official endorsement should be inferred.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Robinson CV, Sali A, Baumeister W. The molecular sociology of the cell. Nature. 2007;450:973–982. doi: 10.1038/nature06523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alber F, Dokudovskaya S, Veenhoff LM, Zhang W, Kipper J, Devos D, Suprapto A, Karni-Schmidt O, Williams R, Chait BT, Sali A, Rout MP. The molecular architecture of the nuclear pore complex. Nature. 2007;450:695–701. doi: 10.1038/nature06405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmid EM, McMahon HT. Integrating molecular and network biology to decode endocytosis. Nature. 2007;448:883–888. doi: 10.1038/nature06031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joglekar AP, Bloom K, Salmon ED. In vivo protein architecture of the eukaryotic kinetochore with nanometer scale accuracy. Curr Biol. 2009;19:694–699. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro L, McAdams HH, Losick R. Why and how bacteria localize proteins. Science. 2009;326:1225–1228. doi: 10.1126/science.1175685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chevance FF, Hughes KT. Coordinating assembly of a bacterial macromolecular machine. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:455–465. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams DW, Errington J. Bacterial cell division: assembly, maintenance and disassembly of the Z ring. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:642–653. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer N, Hahn J, Dubnau D. Multiple interactions among the competence proteins of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65:454–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gitai Z. New fluorescence microscopy methods for microbiology: sharper, faster, and quantitative. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12:341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Driks A, Roels S, Beall B, Moran CP, Jr, Losick R. Subcellular localization of proteins involved in the assembly of the spore coat of Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 1994;8:234–244. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rout MP, Aitchison JD, Suprapto A, Hjertaas K, Zhao Y, Chait BT. The yeast nuclear pore complex: composition, architecture, and transport mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:635–651. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guberman JM, Fay A, Dworkin J, Wingreen NS, Gitai Z. PSICIC: noise and asymmetry in bacterial division revealed by computational image analysis at sub-pixel resolution. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:e1000233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reshes G, Vanounou S, Fishov I, Feingold M. Cell shape dynamics in Escherichia coli. Biophys J. 2008;94:251–264. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.104398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piggot PJ, Hilbert DW. Sporulation of Bacillus subtilis. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7:579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henriques AO, Moran CP., Jr Structure, assembly, and function of the spore surface layers. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2007;61:555–588. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Driks A. Bacillus subtilis spore coat. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:1–20. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.1-20.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Driks A. The Bacillus anthracis spore. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30:368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warth AD, Ohye DF, Murrell WG. The composition and structure of bacterial spores. J Cell Biol. 1963;16:579–592. doi: 10.1083/jcb.16.3.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piggot PJ, Coote JG. Genetic aspects of bacterial endospore formation. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:908–962. doi: 10.1128/br.40.4.908-962.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramamurthi KS, Lecuyer S, Stone HA, Losick R. Geometric cue for protein localization in a bacterium. Science. 2009;323:1354–1357. doi: 10.1126/science.1169218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng LB, Donovan WP, Fitz-James PC, Losick R. Gene encoding a morphogenic protein required in the assembly of the outer coat of the Bacillus subtilis endospore. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1047–1054. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.8.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Webb CD, Decatur A, Teleman A, Losick R. Use of green fluorescent protein for visualization of cell-specific gene expression and subcellular protein localization during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5906–5911. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5906-5911.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim H, Hahn M, Grabowski P, McPherson DC, Otte MM, Wang R, Ferguson CC, Eichenberger P, Driks A. The Bacillus subtilis spore coat protein interaction network. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:487–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang KH, Isidro AL, Domingues L, Eskandarian HA, McKenney PT, Drew K, Grabowski P, Chua MH, Barry SN, Guan M, Bonneau R, Henriques AO, Eichenberger P. The coat morphogenetic protein SpoVID is necessary for spore encasement in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2009;74:634–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozin AJ, Henriques AO, Yi H, Moran CP., Jr Morphogenetic proteins SpoVID and SafA form a complex during assembly of the Bacillus subtilis spore coat. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1828–1833. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.7.1828-1833.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takamatsu H, Kodama T, Nakayama T, Watabe K. Characterization of the yrbA gene of Bacillus subtilis, involved in resistance and germination of spores. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4986–4994. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.16.4986-4994.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharp MD, Pogliano K. An in vivo membrane fusion assay implicates SpoIIIE in the final stages of engulfment during Bacillus subtilis sporulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14553–14558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imamura D, Kuwana R, Takamatsu H, Watabe K. Localization of proteins to different layers and regions of Bacillus subtilis spore coats. J Bacteriol. 192:518–524. doi: 10.1128/JB.01103-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J, Fitz-James PC, Aronson AI. Cloning and characterization of a cluster of genes encoding polypeptides present in the insoluble fraction of the spore coat of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3757–3766. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.12.3757-3766.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waller LN, Fox N, Fox KF, Fox A, Price RL. Ruthenium red staining for ultrastructural visualization of a glycoprotein layer surrounding the spore of Bacillus anthracis and Bacillus subtilis. J Microbiol Methods. 2004;58:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luft JH. Ruthenium red and violet. I. Chemistry, purification, methods of use for electron microscopy and mechanism of action. Anat Rec. 1971;171:347–368. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091710302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramamurthi KS, Losick R. ATP-driven self-assembly of a morphogenetic protein in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Cell. 2008;31:406–414. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Little S, Driks A. Functional analysis of the Bacillus subtilis morphogenetic spore coat protein CotE. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42:1107–1120. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozin AJ, Samford CS, Henriques AO, Moran CP., Jr SpoVID guides SafA to the spore coat in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3041–3049. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.10.3041-3049.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krajcikova D, Lukacova M, Mullerova D, Cutting SM, Barak I. Searching for protein-protein interactions within the Bacillus subtilis spore coat. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:3212–3219. doi: 10.1128/JB.01807-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen G, Driks A, Tawfiq K, Mallozzi M, Patil S. Bacillus anthracis and Bacillus subtilis spore surface properties and transport. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 76:512–518. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ball DA, Taylor R, Todd SJ, Redmond C, Couture-Tosi E, Sylvestre P, Moir A, Bullough PA. Structure of the exosporium and sublayers of spores of the Bacillus cereus family revealed by electron crystallography. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68:947–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aronson AI, Fitz-James P. Structure and morphogenesis of the bacterial spore coat. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:360–402. doi: 10.1128/br.40.2.360-402.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Redmond C, Baillie LW, Hibbs S, Moir AJ, Moir A. Identification of proteins in the exosporium of Bacillus anthracis. Microbiology. 2004;150:355–363. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26681-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boydston JA, Yue L, Kearney JF, Turnbough CL., Jr The ExsY protein is required for complete formation of the exosporium of Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:7440–7448. doi: 10.1128/JB.00639-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Youngman P, Perkins JB, Losick R. Construction of a cloning site near one end of Tn917 into which foreign DNA may be inserted without affecting transposition in Bacillus subtilis or expression of the transposon-borne erm gene. Plasmid. 1984;12:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(84)90061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waller LN, Stump MJ, Fox KF, Harley WM, Fox A, Stewart GC, Shahgholi M. Identification of a second collagen-like glycoprotein produced by Bacillus anthracis and demonstration of associated spore-specific sugars. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:4592–4597. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.13.4592-4597.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Related to Figure 1. Previously uncharacterized genetic interactions with cotE (A) and safA (B).

Table S1: Related to Figure 1E. Presents previously characterized genetic interactions used to construct the interaction network in Figure 1E.

Figure S2: Related to Figure 2. These data are of a proof-of-principle experiment done with dual-labeled cells, demonstrating directly that two coat proteins in the same cell are significantly separated.

Table S2: Related to Figure 2. Presents the PSICIC data in tabular form, as well as statistics.

Table S3: List of bacterial strains used in this study.