Abstract

Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) play an essential role in systemic waste clearance by effective endocytosis of blood-borne waste macromolecules. We aimed to study LSECs’ scavenger function during aging, and whether age-related morphological changes (eg, defenestration) affect this function, in F344/BN F1 rats. Endocytosis of the scavenger receptor ligand formaldehyde-treated serum albumin was significantly reduced in LSECs from old rats. Ligand degradation, LSEC protein expression of the major scavenger receptors for formaldehyde-treated serum albumin endocytosis, stabilin-1 and stabilin-2, and their staining patterns along liver sinusoids, was similar at young and old age, suggesting that other parts of the endocytic machinery are affected by aging. Formaldehyde-treated serum albumin uptake per cell, and cell porosity evaluated by electron microscopy, was not correlated, indicating that LSEC defenestration is not linked to impaired endocytosis. We report a significantly reduced LSEC endocytic capacity at old age, which may be especially important in situations with increased circulatory waste loads.

Keywords: Aging, Hepatic sinusoid, Porosity, Stabilin, Scavenger endothelial cells

A striking functional characteristic of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) is their high endocytic activity toward a wide range of blood-borne macromolecules (1,2). For this vital function, LSECs are equipped with high-affinity endocytosis receptors and well-developed clathrin-mediated endocytic machinery allowing efficient uptake and degradation of foreign and physiological waste products, including connective tissue macromolecules (hyaluronan, chondroitin sulfate, procollagen propeptides, and collagen alpha-chains (1,3)), heparin (4), lysosomal enzymes (5), modified proteins and lipoproteins (6–8), soluble IgG complexes (9), and microbial CpG motifs (10). Although LSECs play a pivotal role in the removal of these substances from the circulation, few studies have addressed the clearance function of these cells at old age (11) and reported findings are not conclusive.

One study in rat (12) reported no change with aging in LSEC endocytic capacity for colloidal (heat-aggregated) albumin following intravenous injection and subsequent separation of liver cells, whereas two other similar in vivo studies (13,14) showed a significant reduction in the LSEC uptake of azoaniline–albumin (13) and sulfanilate–azo-albumin (14) in old versus young rats. A recent study in mice, using in vivo microscopy (15), showed reduced uptake of two other scavenger receptor (SR) ligands, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-advanced glycation end product-albumin and FITC–formaldehyde-treated serum albumin (FITC-FSA) in the centrilobular areas of the liver sinusoid of old animals compared with middle-aged young adult and prepubertal animals. However, more detailed studies on aging LSECs endocytic capacity are lacking.

LSECs are strategically located between the blood stream and the hepatocytes, where they play vital roles in waste clearance via clathrin-mediated endocytosis and mechanical filtering via their fenestrae. These fenestrae are grouped in sieve plates (16) and are true pores (approximately 100–150 nm in diameter) lacking a diaphragm or underlying basal lamina, and their diameter dictates which substances can pass from the blood to hepatocytes. Several factors, including hormones, cytokines, alcohol, and nicotine (17,18), influence this porosity and thus the liver-sieve filtering function. LSECs’ porosity (percentage of surface area occupied by fenestrae) is also affected by aging; studies in human, baboon, rat, and mouse (15,19–22) have shown significant defenestration, liver endothelial thickening, and development of basal lamina and collagen in the space of Disse in old individuals. These age-related changes have been named pseudocapillarization to differentiate them from capillarization seen in liver cirrhosis (19).

The aim of the present article was to examine, as a function of age, LSEC endocytosis of FSA, a well-characterized SR-mediated endocytosis model for these cells (3,5,6). We also further examined LSECs’ fenestration in young and old rats to determine whether their cell porosity correlates with their endocytic capacity.

METHODS

Reagents

Collagenase was from Worthington Biochemical Corporation (Lakewood, NJ); carrier-free Na125I from PerkinElmer Norge AS (Oslo, Norway); bovine serum albumin from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH); human serum albumin from Octapharma (Ziegelbrucke, Switzerland), Percoll, PD-10 columns (Sephadex G-25), and donkey-anti-rabbit antibody horseradish peroxidase conjugate from GE Healthcare (Uppsala, Sweden); bovine collagen type I (Vitrogen 100) from Cohesion Technologies (Palo Alto, CA); RPMI 1640 (with 20 mM sodium bicarbonate, 0.006% penicillin, and 0.01% streptomycin) from Gibco BRL (Roskilde, Denmark); Falcon cell culture plates from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA); RD-DC Protein Assay from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA); and protease inhibitors from Roche (Mannheim, Germany). Stabilin-1 and stabilin-2 antibodies were made as described (23,24). Alexa-488 goat-anti-rabbit was from Invitrogen (Oslo, Norway) and DRAQ-5 from Biostatus Limited (Leicestershire, UK).

Animals

F344/BN F1 hybrid 24- to 26-month-old male rats from National Institute on Ageing (Bethesda, MD) were housed in the rodent facilities at the Animal Research Unit, University of Tromsø greater than or equal to 2 months before use. Young adult animals (4–8 months) were bred at the Animal Research Unit from F344 female and BN male breeders obtained from National Institute on Ageing colonies and housed with the old animals to avoid in-house variations. The animals were fed standard chow (Scanbur BK, Nittedal, Norway) ad libitum. All experimental protocols were approved by the Norwegian Animal Research Authority according to the “Norwegian Animal Experimental and Scientific Purposes Act, 1986.”

Cell Isolation

Preparation of LSECs was performed by collagenase perfusion of rat livers, low-speed differential centrifugation to remove hepatocytes, and density sedimentation of the nonparenchymal cells on 25%–45% Percoll gradients, as described (25). Following a panning step to remove Kupffer cells, purified LSECs in serum-free RPMI 1640 were seeded onto 24-well collagen-coated tissue culture plates at a density of 1 million cells per well, washed after 1 hour, and allowed to spread for 1 hour before use. The average number of cells attached per well was 333,410 (SD = 82,807, n = 9) for young group, and 343,451 (SD = 63,992, n = 10) for old group, with more than 97% being judged as LSEC (by scanning electron microscopy [EM]).

Ligands and Labeling

FSA (26) was stored at −70°C and thawed at 60°C for 1 hour before use. FSA was labeled with carrier-free Na125I (3). The resulting specific radioactivity was approximately 2.5 × 106 cpm/μg protein.

Tissue Preparation

Livers were perfused in situ through the portal vein with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) prior to perfusion fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS with 0.02 M sucrose, pH 7.4. For light microscopy, sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or with the van Gieson technique. Tissues for transmission/scanning EM were postfixed in McDowell’s fixative (27). For frozen tissue sections, the median liver lobe was ligated and resected immediately after PBS perfusion, and tissue samples were embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT Compound (Sakura Finetek, CA) before snap freezing in liquid nitrogen.

Endocytosis Experiments

Primary 2-hour LSEC cultures established from old/young rats in 2-cm2 wells were supplied with fresh serum-free RPMI 1640 containing 1% human serum albumin, 125I-FSA (0.1 μg/mL) and different concentrations of unlabeled FSA (0–128 μg/mL), and incubated for 2 hours at 37°C to measure endocytosis (3,6). The spent medium along with one wash of 500 μL PBS were transferred to a tube containing 500 μL of 20% trichloroacetic acid, which precipitates protein of high molecular mass. The amount of intracellular degradation products released after endocytosis was determined by measuring acid-soluble radioactivity in the supernatant and subtracting the acid-soluble radioactivity (representing free iodine) in the supernatant of cell-free control wells. Cell-associated ligand was quantified by measuring sodium dodecyl sulfate soluble radioactivity in the remaining cells minus the radioactivity of nonspecific surface binding in cell-free control wells. The total endocytosis was determined by adding the cell-associated and acid-soluble radioactivity.

To enable comparison between animals, parallel cultures of 2-hour LSECs were established on collagen-coated cover slides in 2-cm2 wells, fixed, and prepared for scanning EM (see later) for cell counting and purity/morphology assessment.

Immunohistochemistry

Frozen tissue sections (5 μm) from the median liver lobe of four young and four old rats were fixed for 5 minutes with 4% paraformaldehyde; blocked with 2% goat serum and 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS; labeled with an antiserum to full-length rat stabilin-2 (anti-rS2 (23)), diluted 1:1,200, or with an antiserum to the cytoplasmic tail of recombinant human stabilin-1 (anti-hS1 (24,28)), diluted 1:1,600, for 1 hour at room temperature; and visualized with Alexa488-goat-anti-rabbit, diluted 1:200. Sections were analyzed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (Zeiss LSM 510 microscope; Carl Zeiss, Germany).

Transmission EM

Tissue blocks were prepared as described (19) from the left liver lobe of four young/old rats, and two blocks from each animal were selected at random for sectioning and analysis. Ultrathin sections (70–90 nm) from each block were analyzed using a JEM-1010 microscope (JEOL Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). Ten fields per block were chosen at random by an operator blinded to tissue category, and photographed (8,000×) for the evaluation of liver tissue structure and measurements of endothelial cell thickness, fenestration (number and diameter), collagen (area of collagen per total length of sinusoids), and basal lamina deposits (% of length of deposits per total length of sinusoids) in the space of Disse.

Scanning EM

McDowell’s fixed 2-hour LSEC cultures were treated with 1% tannic acid in 0.15 mol/L cacodylic buffer, 1% OsO4 in 0.1 mol/L cacodylic buffer, dehydrated in ethanol, and incubated in hexamethyldisilazane (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), before coating with 10-nm gold/palladium alloys. Ten cells from each preparation were chosen at random and photographed at 10,000× magnification, and fenestrae diameter, number of fenestrae, and porosity (percentage of surface area occupied by fenestrae) were analyzed using Image J software (29).

To evaluate cell number and culture purity, the cultures were divided into five areas, and pictures were taken at random at 750× magnifications within each area, for total and differential counting (see Cell Isolation section).

Western Blots

Tow-hour LSEC cultures (9.6 cm2) were solubilized in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors (3) and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting (23) with anti-rS2 antiserum (1:200) or anti-hS1 antiserum (1:400) overnight at 4°C, washed, and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with donkey anti-rabbit antibody horseradish peroxidase conjugate (1:20,000). Immunoreactive protein bands were visualized with luminol.

Statistics

The statistical calculations were performed with GraphPad Prism version 4.00 for Macintosh (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) and SPSS software for Windows version 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). p Values < .05 were considered significant. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

Structural Age-Related Changes of LSECs in the Intact Liver

Distinct age-related changes in the liver sinusoid, such as defenestration, increased thickness of the endothelium, basal lamina, and collagen depositions in the space of Disse, were reported in F344 rats (19). Our present studies were carried out with the hybrid F344/BN F1 rat, which is a healthier model for aging (30).

Light microscopy.—

Light microscopy examination of liver sections from young (4–8 months, n = 4) and old (26–28 months, n = 4) rats (Supplementary Figure 1) revealed slightly increased connective tissue in the liver capsule and around nonsinusoidal vessels but no significant changes in the sinusoids of the old livers.

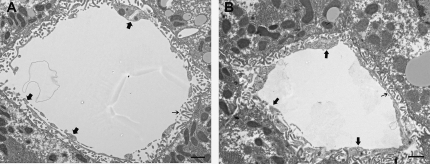

Transmission EM.—

Results are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. The most striking finding was a significant decrease in the number of fenestrae in the liver sinusoidal endothelium and an increased endothelial thickness in the old rats, whereas the fenestrae diameter was unchanged. No age group difference in collagen or basal lamina deposits as described in F344 rats and other species (11,15,20,21,31) was seen in the present rat model. The stellate cells of the old rats had larger lipid droplets (not shown). Activated stellate cells were not observed.

Figure 1.

General appearance of liver sinusoids in young and old F344/BN1 F1 rats. Transmission electron micrographs of a young (A) and an old (B) rat liver sinusoid. Large arrows point to endothelium, and small arrows point to fenestrae. Increased endothelial thickness and reduced numbers of fenestrae are observed in the old liver (B); scale bars 1 μm.

Table 1.

Transmission Electron Microscopy Examination of Liver Tissue From Young and Old Rats

| Structural Feature | Young Rats (n = 4) | Old Rats (n = 4) | Fractional Change With Age |

| Fenestrae/10 μm | 5.63 ± 0.31 | 3.82 ± 0.41 | 0.69* |

| Fenestrae diameter (nm) | 143.26 ± 0.84 | 141.20 ± 3.65 | 0.98n.s. |

| Endothelial porosity (% fenestrae/sinusoid) | 7.50 ± 1.44 | 5.08 ± 1.02 | 0.67* |

| Endothelial thickness (nm) | 191.42 ± 6.89 | 264.19 ± 4.78 | 1.38** |

| Collagen (area of collagen/total sinusoidal length) | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.05 | 1.02n.s. |

| Basal lamina (% length of basal lamina/total sinusoidal length) | 1.43 ± 0.38 | 1.77 ± 0.37 | 1.23n.s. |

Notes: Results are presented as mean ± SEM. n.s. = not statistically significant.

*p < .05; **p < .005.

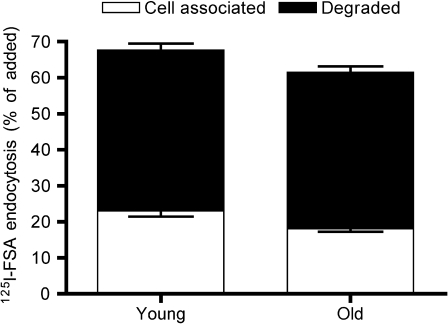

The Endocytic Capacity of LSEC Is Markedly Impaired in Old Rats

The endocytosis of 125I-labeled FSA in cultured LSECs freshly isolated from young (4–8 months, n = 9) and old (26–30 months, n = 10) rats was studied (Figures 2 and 3). At low ligand concentrations (0.1 μg/mL), the endocytosis was very effective in both age groups (Figure 2). However, at higher ligand concentrations (1–128 μg/mL), cells from young rats were markedly more effective than cells from old rats (Figure 3). Student’s t tests performed for each ligand concentration showed a significant difference (p < .05) in endocytosis between the two age groups at all concentrations except the lowest. When using a saturation-binding plot (32), Vmax (maximal internalization rate) was significantly reduced in cells from old rats, whereas Kd values (ligand concentration at half-maximal internalization rate) were similar (young: 11.35 ± 1.65 μg/mL and old: 10.97 ± 2.74 μg/mL). The uptake capacity at the curve flattening point (around 32 μg/mL) was 2.710 ± 0.882 pg/cell/2 hours in the young rat cultures and 1.744 ± 0.281 pg/cell/2 hours in cultures from old rats, indicating reduced LSEC endocytic capacity at old age. The level of degradation as a function of total endocytosis for each ligand concentration was similar in both groups (not shown).

Figure 2.

Liver sinusoidal endothelial cell (LSEC) endocytosis of low doses of formaldehyde-treated serum albumin (FSA). Primary LSEC cultures from young (4–8 months, n = 9) and old (26–30 months, n = 10) rats were incubated with 125I-FSA (0.1 μg/mL) for 2 hours at 37°C. Endocytosis was measured as described in Material and Methods, and results are given in percent of added radioactivity. Open bars represent cell-associated ligand (−SE), whereas black bars represent degraded ligand (+SE). Total endocytosed radioactivity represents the sum of cell-associated and degraded ligand radioactivity.

Figure 3.

Endocytic capacity of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) from young and old rats. The figure shows the capacity of LSEC cultures from young (4–8 months, n = 9; triangles) and old (26–30 months, n = 10; circles) rats to endocytose formaldehyde-treated serum albumin (FSA). The cultures were incubated with 125I-FSA (0.1 μg/mL) alone or together with nonlabeled FSA (1–128 μg/mL) for 2 hours at 37°C. Error bars represent SE.

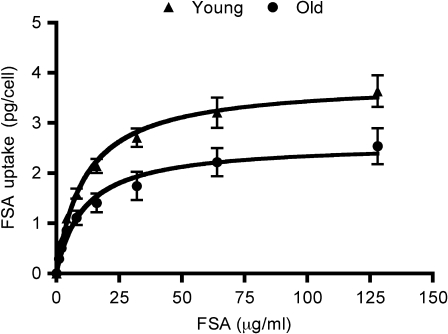

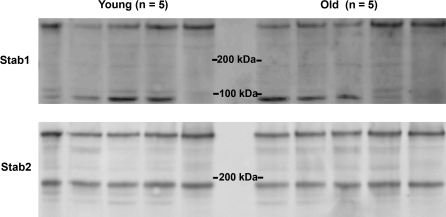

Expression of Stabilin-1 and Stabilin-2 in LSECs From Young and Old Rats

Following intravenous injections in rats, 125I-FSA is taken up almost exclusively in LSEC, via SR-mediated endocytosis (6). The two major SRs for FSA in these cells are stabilin-1 (unpublished results) and stabilin-2 (23). We therefore analyzed the relative expression of the stabilins along liver sinusoids and in cell lysates of freshly isolated LSECs, from young and old rats.

“Confocal microscopy” of liver cryosections labeled with stabilin-1 and stabilin-2 antibodies, respectively, showed a similar sinusoidal distribution pattern for both receptors in young and old livers (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Expression of stabilin-1 and stabilin-2 in the liver sinusoids. Confocal laser scanning micrographs of frozen liver sections from young (A and C) and old (B and D) rats labeled with rabbit polyclonal antisera toward stabilin-1 (Stab1; A and B) and stabilin-2 (Stab2; C and D). Immune labeling was visualized with an Alexa-488-goat anti-rabbit antibody (green fluorescence, arrows), and nuclei stained with Draq-5 (blue); bars = 50 μm.

“Western blot analyses” of LSEC lysates did not show a consistent difference in the expression of the stabilins between the age groups (Figure 5). Both overnight and short (20 minutes) incubations with primary antibody were performed to determine if the antibody incubation time influenced the results, as suggested by Dittmer and Dittmer (33); but no such difference was revealed (not shown). In Figure 5, the amount loaded in each lane was 2.5 μg protein. Normalizing with β-actin did not reveal any age group differences in stabilin expression either (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Western blots of stabilins in liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. The upper panel shows the expression of stabilin-1 (Stab1), and the lower panel the expression of stabilin-2 (Stab2) in cells from five young (4–8 months) and five old (26–30 months) rats. Cell protein loaded: 2.5 μg per lane. Band sizes were estimated by comparison with a biotinylated protein ladder. A donkey anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase conjugate antibody was used to visualize the bands. Rat stabilin-1 Western blots typically show one or two bands of approximately 300 and 90 kDa. The 90 kDa protein is a breakdown product of the 300 kDa protein and arises due to the reduced stability of stabilin-1. Rat stabilin-2 Western blots typically show bands of approximately 270 and 180 kDa in roughly equal proportions (23). Pixel densitometry measurements of the two main bands (measured with Fuji Multiguage software) in each of the stabilin-1 and stabilin-2 blots showed: Stabilin-1—young: 257 ± 60; old: 272 ± 56; stabilin-2—young: 332 ± 53; old: 315 ± 30 (AU/pixel2, mean ± SD).

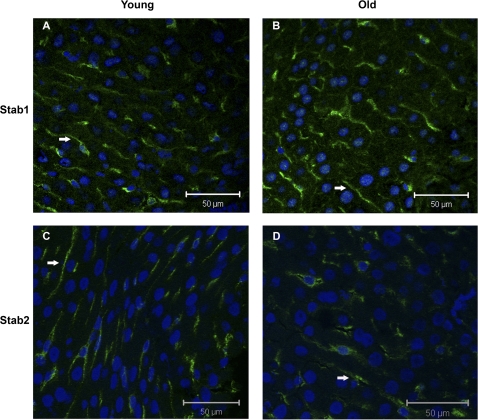

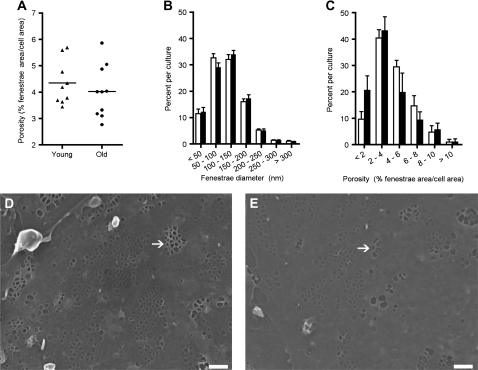

Fenestration in Cultured LSECs

Measuring porosity (% fenestrated area per total cell surface area) of cultured LSECs on scanning EM micrographs revealed a slightly lower average porosity of cells in LSEC cultures from old versus young rats (Figure 6A; old: 4.023 ± 0.312%, n = 10; young: 4.347 ± 0.28%, n = 9), but this difference was not significant. The intra-culture distribution of values for fenestrae diameter was equal in the two age groups (Figure 6B), but there was a shift toward a higher percentage of cells with low porosity in cultures from old animals (Figure 6C). Notably, no LSECs were found to be totally defenestrated in any culture from either age group.

Figure 6.

Morphological assessments of liver sinusoidal endothelial cell cultures. Panel (A) shows the average porosity (% fenestrae area per cell area) in cultured liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) from 9 young and 10 old rats (2-hour-old culture). Panel (B) shows the frequency of fenestrae with a certain diameter (range: 50–300 nm) within the same cultures. Panel (C) shows the distribution of porosity within the analyzed cells in the cultures, calculated as the frequency of each porosity range, which varied from 1 to more than 10% fenestrated area per cell area. Young; triangles (A), black bars (B and C). Old; circles (A), white bars (B and C). (D and E) Scanning electron micrographs of LSEC cultures from a young (D) and an old (E) rat. The cultures were fixed 2 hours after seeding. Fenestrae were mostly arranged in sieve plates in cells from both age groups; some as mesh-like sieve plates (arrows); bars 1 μm.

There were no marked qualitative differences in the LSEC fenestrae between the age groups. Besides typical sieve plate formation, other fenestration patterns were also found, for example mesh-like sieve plates (Figure 6D and E), which appeared with almost equal frequency in cultures from young and old rats. There were no significant differences in gap formation (holes >300 nm).

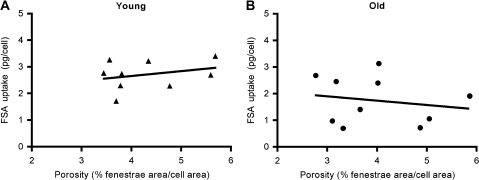

LSEC Endocytic Capacity Is Not Correlated With Cell Porosity

To study the extent of correlation between endocytic capacity and cell porosity, the uptake (picograms per cell per 2 hours) of FSA at the curve flattening point (32 μg/mL) on the endocytic capacity curve was plotted against the average porosity of cells isolated from the same animals (Figure 7A and B). Regression analysis showed no significant correlation between these parameters either within or between the age groups, indicating that changes in LSEC fenestration not necessarily leads to changes in endocytic activity.

Figure 7.

Relationship between endocytic capacity and porosity. (A and B) Regression analysis of endocytic capacity (picograms of formaldehyde-treated serum albumin [FSA] taken up per cell during 2-hour incubation with 32 μg/mL FSA) and porosity of liver sinusoidal endothelial cell cultures from the same animals (young rats: n = 9 and old rats: n = 10) showed no significant correlation within or between age groups.

DISCUSSION

Several age-related changes have been documented in the liver, including reduced organ volume, accumulation of lipofuscin in hepatocytes, diminished hepatobiliary functions, a shift in the expression of a variety of proteins (34), and impaired intrinsic metabolic drug clearance (35). The sinusoids also show marked changes with aging, and the term “pseudocapillarization” was launched to describe the age-associated morphological changes (19–22), such as defenestration, endothelial thickening, and partial depositions of basal lamina and collagen in the space of Disse. In accordance with previous studies in F344 rats (19), C57BL/6 mice (15,22), baboons (21), and humans (20), old F344/BN F1 rats also showed increased endothelial thickness and reduced endothelial porosity. However, an increase in collagen or basal lamina deposits was not observed in this rat strain, suggesting that changes in the endothelial cells precede matrix deposition in the development of pseudocapillarization. Because little is known about the mechanism behind these changes or whether they affect the functionality of LSECs, we attempted to answer this question by comparing endocytic capacity for SR ligands, SR expression, and the fenestration of LSECs in cultures established from young and old rats.

We found that LSECs’ capacity to take up FSA was markedly reduced in cells isolated from the old-age group. Endocytosis is a well-studied process but due to its biological and kinetic complexity it is very difficult to establish mathematical models to quantify it (32). We therefore compared the results by two different statistical tests. The maximal internalization rate, Vmax, was significantly reduced, whereas the Kd, measuring the ligand concentration at half-maximal internalization rate, was similar in the two age groups. However, the endocytic process involves not only receptor binding but also ligand internalization, retroendocytosis, intracellular trafficking of ligand to degradation organelles, ligand degradation, and release from the cell of low Mr degradation products, which all together cannot be described only by classical kinetics. Thus, t tests were performed for each ligand concentration given to the cells; a significant difference was found for all concentrations except the lowest.

The SRs are a large family of receptors characterized by the recognition of a wide range of molecules (mostly negatively charged). LSECs express a number of these, including SR-A (23,36), SR-B (SR-B1 and CD36 [albeit in very small amounts]) (37), and SR-H (stabilin-1/FEEL-1 and stabilin-2/FEEL-2/HARE) (23,24,28,38,39). However, on LSECs, the workhorse SR seems to be stabilin-2 (possibly together with stabilin-1 (28)) based on the following: (i) SR-A–knockout mice clear SR ligands equally well as wild-type mice (40–42) and cultured LSECs from these knockout mice endocytose and degrade SR ligands equally well as wild types (43,44); (ii) an antibody to CD36 that inhibits CD36 mediated uptake of SR ligands in other cells has no effect on uptake of SR ligands by LSECs (45); (iii) an antibody to stabilin-2 inhibits the LSEC uptake of hyaluronan by more than 80% and other SR ligands by more than 50% (23); and (iv) both stabilin-1 and stabilin-2 mediate the uptake of SR ligands in cultured LSECs (28). FSA uptake in LSEC is inhibited more than 50% by an anti-stabilin-2 antibody (23), and this ligand also shows high degree of colocalization with stabilin-1 in immuno-EM studies (unpublished findings). We therefore focused our interest on the study of stabilin-1 and stabilin-2 expression in the two age groups; however, there were no consistent quantitative or qualitative differences observed in protein expression, protein size, or sinusoidal staining patterns, suggesting unchanged stabilin levels in LSECs.

Taken together, the observed reduction in endocytic capacity for FSA in LSECs from old rats appears to be unrelated to the level of stabilin-1 or stabilin-2 expression. Likewise, the level of degradation as a function of total endocytosis for each ligand concentration was also similar in both groups, indicating that degradation of internalized ligands are effective also at old age, thus suggesting that other parts of the endocytic machinery are affected by aging.

Fenestration of Cells in Culture

Although we found a significant difference in porosity in the sinusoidal endothelium of young and old rat livers (Figure 1; Table 1), the differences in porosity of isolated cells were less marked (Figure 6). The cultured cells of both age groups were well fenestrated, although the cultures from old animals showed a tendency toward lower average porosity (not significant) and had more cells with fewer fenestrations than the young cultures. No cell was completely defenestrated in any cultures, and in accordance with the findings in whole livers, there were no changes in the mean fenestrae diameter or in diameter distribution between the age groups. We conclude that fenestrae formation is an intrinsic quality that LSEC maintain at old age, as short-term cultured cells are able to form them. O’Reilly and colleagues (46) also reported fenestrae in old rat LSECs cultivated for 18 hours. However, after a few days in culture fenestrae are usually lost (47), indicating that the fenestration maintenance factors come from an external (non-LSEC) source, as indicated in previous studies (48).

Fenestration Versus Endocytosis

When comparing the LSECs’ endocytic capacity for FSA in vitro with the cell porosity in parallel cultures isolated from the same animal, no significant correlation was found between these variables in either of the age groups. This suggests that reduced fenestration not necessarily leads to impaired endocytic activity, although both characteristics are affected by aging. This notion is in accordance with the finding by Martinez and colleagues (47) that cultivation of LSECs under 5% oxygen tension, as opposed to atmospheric oxygen tension, significantly improved SR-mediated endocytic activity, but not the cell fenestration, in a time-course analysis. The lack of correlation between LSEC fenestration and endocytic capacity is not surprising when considering that scavenger endothelial cells (2), a functionally distinct cell population of vertebrates to which the mammalian LSECs belong, are well conserved in evolution but not always fenestrated (2,49). In bony fishes, as in mammals, LSECs are fenestrated (50), but unlike their mammalian counterparts, fish LSECs are not very effective in endocytosis (49,51,52). Instead, the typical scavenger endothelial cells in aquatic species, with analogous functions to the mammalian LSECs, are located in the gills of jawless and cartilage fishes and in heart or kidney of bony fishes (2). However, in amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals the LSECs are the major scavenger endothelial cells (2).

“Traffic Jam” Hypothesis

Based on our observations that (i) LSECs isolated from old rats have a decreased endocytic capacity (but the same ability to degrade endocytosed ligand as LSECs from young rats); (ii) stabilin-1 and stabilin-2 are equally expressed in LSECs from young and old rats; and (iii) LSECs in livers from old rats have an increased thickness compared with LSECs in young rats, we hypothesize that the decrease in endocytic capacity of LSECs from old rats is due (at least in part) to the increased endothelial thickness, which slows down the transport of internalized ligand to the degradative part of the endo/lysosomal compartment.

Implications of Reduced LSEC Endocytic Capacity in Old Livers

The liver has a large metabolic reserve capacity. Therefore, the reduced endocytic capacity of old LSECs may not have a major impact in a healthy old individual, but in situations where the organism is subjected to a sudden increase in the amount of blood–borne waste, for example, in massive trauma, acute tumor lysis, and/or disseminated intravascular coagulation, the old liver may not be able to handle these situations effectively. This will lead to an additional burden on the kidneys and blood–brain barrier, worsening the outcome in elderly patients. Of note, the reduced endocytic capacity was noticeable at all FSA concentrations except for the lowest, meaning that the “safety margin” is significantly decreased in old livers. This may also be an important issue following liver resection surgery in old patients, and for the use of old livers for transplantation, an issue that has been raised previously (53). Furthermore, an age-related decrease in LSEC endocytosis combined with the increased circulatory waste burden in long-term conditions, such as diabetes and obesity, where there is an increased plasma concentration of modified proteins and lipoproteins (namely advanced glycation end products and oxidized low density lipoproteins) may also exacerbate the negative effects of these conditions and increase the risk of extrahepatic deposition of atherogenic substances. The effects of dietary interventions (54) such as short- or long-term caloric restriction or caloric restriction mimetics on the endocytic capacity of the liver remains to be elucidated but would be an interesting study for the future.

FUNDING

The work was supported by the Norwegian Research Council (grant number 153483/V50); the Tromsø University Research Foundation, Norway; the National Institutes of Health, USA (grant number 1.R21 AG026582-01A1); the Basque Government, Spain (grant number BFI 05.525); the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council; and the Ageing and Alzheimer’s Research Foundation, Australia.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material can be found at: http://biomed.gerontologyjournals.org/

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Anja Vepsa, Helga-Marie Bye, and Randi Olsen for excellent support in tissue preparation for light microscopy and EM.

References

- 1.Smedsrod B. Clearance function of scavenger endothelial cells. Comp Hepatol. 2004;3(suppl 1):S22. doi: 10.1186/1476-5926-2-S1-S22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seternes T, Sorensen K, Smedsrod B. Scavenger endothelial cells of vertebrates: a nonperipheral leukocyte system for high-capacity elimination of waste macromolecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7594–7597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102173299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malovic I, Sorensen KK, Elvevold KH, et al. The mannose receptor on murine liver sinusoidal endothelial cells is the main denatured collagen clearance receptor. Hepatology. 2007;45:1454–1461. doi: 10.1002/hep.21639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oie CI, Olsen R, Smedsrod B, Hansen JB. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells are the principal site for elimination of unfractionated heparin from the circulation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G520–G528. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00489.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elvevold K, Simon-Santamaria J, Hasvold H, McCourt P, Smedsrod B, Sorensen KK. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells depend on mannose receptor-mediated recruitment of lysosomal enzymes for normal degradation capacity. Hepatology. 2008;48:2007–2015. doi: 10.1002/hep.22527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blomhoff R, Eskild W, Berg T. Endocytosis of formaldehyde-treated serum albumin via scavenger pathway in liver endothelial cells. Biochem J. 1984;218:81–86. doi: 10.1042/bj2180081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Rijke YB, Biessen EA, Vogelezang CJ, van Berkel TJ. Binding characteristics of scavenger receptors on liver endothelial and Kupffer cells for modified low-density lipoproteins. Biochem J. 1994;304(Pt 1):69–73. doi: 10.1042/bj3040069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smedsrod B, Melkko J, Araki N, Sano H, Horiuchi S. Advanced glycation end products are eliminated by scavenger-receptor-mediated endocytosis in hepatic sinusoidal Kupffer and endothelial cells. Biochem J. 1997;322(Pt 2):567–573. doi: 10.1042/bj3220567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovdal T, Andersen E, Brech A, Berg T. Fc receptor mediated endocytosis of small soluble immunoglobulin G immune complexes in Kupffer and endothelial cells from rat liver. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 18):3255–3266. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.18.3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin-Armas M, Simon-Santamaria J, Pettersen I, Moens U, Smedsrod B, Sveinbjornsson B. Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) is present in murine liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) and mediates the effect of CpG-oligonucleotides. J Hepatol. 2006;44:939–946. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Couteur DG, Warren A, Cogger VC, et al. Old age and the hepatic sinusoid. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2008;291:672–683. doi: 10.1002/ar.20661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brouwer A, Barelds RJ, Knook DL. Age-related changes in the endocytic capacity of rat liver Kupffer and endothelial cells. Hepatology. 1985;5:362–366. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840050304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caperna TJ, Garvey JS. Antigen handling in aging. II. The role of Kupffer and endothelial cells in antigen processing in Fischer 344 rats. Mech Ageing Dev. 1982;20:205–221. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(82)90088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heil MF, Dingman AD, Garvey JS. Antigen handling in ageing. III. Age-related changes in antigen handling by liver parenchymal and nonparenchymal cells. Mech Ageing Dev. 1984;26:327–340. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(84)90104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito Y, Sorensen KK, Bethea NW, et al. Age-related changes in the hepatic microcirculation in mice. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42:789–797. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wisse E. An ultrastructural characterization of the endothelial cell in the rat liver sinusoid under normal and various experimental conditions, as a contribution to the distinction between endothelial and Kupffer cells. J Ultrastruct Res. 1972;38:528–562. doi: 10.1016/0022-5320(72)90089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braet F, Wisse E. Structural and functional aspects of liver sinusoidal endothelial cell fenestrae: a review. Comp Hepatol. 2002;1:1. doi: 10.1186/1476-5926-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCuskey RS. The hepatic microvascular system in health and its response to toxicants. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2008;291:661–671. doi: 10.1002/ar.20663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Couteur DG, Cogger VC, Markus AM, et al. Pseudocapillarization and associated energy limitation in the aged rat liver. Hepatology. 2001;33:537–543. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLean AJ, Cogger VC, Chong GC, et al. Age-related pseudocapillarization of the human liver. J Pathol. 2003;200:112–117. doi: 10.1002/path.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cogger VC, Warren A, Fraser R, Ngu M, McLean AJ, Le Couteur DG. Hepatic sinusoidal pseudocapillarization with aging in the non-human primate. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38:1101–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warren A, Bertolino P, Cogger VC, McLean AJ, Fraser R, Le Couteur DG. Hepatic pseudocapillarization in aged mice. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:807–812. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCourt PA, Smedsrod BH, Melkko J, Johansson S. Characterization of a hyaluronan receptor on rat sinusoidal liver endothelial cells and its functional relationship to scavenger receptors. Hepatology. 1999;30:1276–1286. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Politz O, Gratchev A, McCourt PA, et al. Stabilin-1 and -2 constitute a novel family of fasciclin-like hyaluronan receptor homologues. Biochem J. 2002;362:155–164. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smedsrod B, Pertoft H. Preparation of pure hepatocytes and reticuloendothelial cells in high yield from a single rat liver by means of Percoll centrifugation and selective adherence. J Leukoc Biol. 1985;38:213–230. doi: 10.1002/jlb.38.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mego JL, Bertini F, McQueen JD. The use of formaldehyde-treated 131-I-albumin in the study of digestive vacuoles and some properties of these particles from mouse liver. J Cell Biol. 1967;32:699–707. doi: 10.1083/jcb.32.3.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDowell EM, Trump BF. Histologic fixatives suitable for diagnostic light and electron microscopy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1976;100:405–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansen B, Longati P, Elvevold K, et al. Stabilin-1 and stabilin-2 are both directed into the early endocytic pathway in hepatic sinusoidal endothelium via interactions with clathrin/AP-2, independent of ligand binding. Exp Cell Res. 2005;303:160–173. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram S.J. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Int. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller RA, Nadon NL. Principles of animal use for gerontological research. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:B117–B123. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.3.B117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le Couteur DG, Fraser R, Hilmer S, Rivory LP, McLean AJ. The hepatic sinusoid in aging and cirrhosis: effects on hepatic substrate disposition and drug clearance. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44:187–200. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birtwistle MR, Kholodenko BN. Endocytosis and signalling: a meeting with mathematics. Mol Oncol. 2009;3:308–320. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dittmer A, Dittmer J. Beta-actin is not a reliable loading control in Western blot analysis. Electrophoresis. 2006;27:2844–2845. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmucker DL. Age-related changes in liver structure and function: implications for disease? Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:650–659. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Butler JM, Begg EJ. Free drug metabolic clearance in elderly people. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47:297–321. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200847050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hughes DA, Fraser IP, Gordon S. Murine macrophage scavenger receptor: in vivo expression and function as receptor for macrophage adhesion in lymphoid and non-lymphoid organs. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:466–473. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malerod L, Juvet K, Gjoen T, Berg T. The expression of scavenger receptor class B, type I (SR-BI) and caveolin-1 in parenchymal and nonparenchymal liver cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2002;307:173–180. doi: 10.1007/s00441-001-0476-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou B, Weigel JA, Fauss L, Weigel PH. Identification of the hyaluronan receptor for endocytosis (HARE) J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37733–37741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adachi H, Tsujimoto M. FEEL-1, a novel scavenger receptor with in vitro bacteria-binding and angiogenesis-modulating activities. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34264–34270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ling W, Lougheed M, Suzuki H, Buchan A, Kodama T, Steinbrecher UP. Oxidized or acetylated low density lipoproteins are rapidly cleared by the liver in mice with disruption of the scavenger receptor class A type I/II gene. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:244–252. doi: 10.1172/JCI119528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki H, Kurihara Y, Takeya M, et al. A role for macrophage scavenger receptors in atherosclerosis and susceptibility to infection. Nature. 1997;386:292–296. doi: 10.1038/386292a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Berkel TJ, Van Velzen A, Kruijt JK, Suzuki H, Kodama T. Uptake and catabolism of modified LDL in scavenger-receptor class A type I/II knock-out mice. Biochem J. 1998;331(Pt 1):29–35. doi: 10.1042/bj3310029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hansen B, Arteta B, Smedsrod B. The physiological scavenger receptor function of hepatic sinusoidal endothelial and Kupffer cells is independent of scavenger receptor class A type I and II. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;240:1–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1020660303855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsumoto K, Sano H, Nagai R, et al. Endocytic uptake of advanced glycation end products by mouse liver sinusoidal endothelial cells is mediated by a scavenger receptor distinct from the macrophage scavenger receptor class A. Biochem J. 2000;352(Pt 1):233–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakajou K, Horiuchi S, Sakai M, et al. CD36 is not involved in scavenger receptor-mediated endocytic uptake of glycolaldehyde- and methylglyoxal-modified proteins by liver endothelial cells. J Biochem. 2005;137:607–616. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Reilly JN, Cogger VC, Le Couteur DG. Old age is associated with ultrastructural changes in isolated rat liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. J Electron Microsc. 2009;59:65–69. doi: 10.1093/jmicro/dfp039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martinez I, Nedredal GI, Oie CI, et al. The influence of oxygen tension on the structure and function of isolated liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. Comp Hepatol. 2008;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1476-5926-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeLeve LD, Wang X, Hu L, McCuskey MK, McCuskey RS. Rat liver sinusoidal endothelial cell phenotype is maintained by paracrine and autocrine regulation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G757–G763. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00017.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sorensen KK, Melkko J, Smedsrod B. Scavenger-receptor-mediated endocytosis in endocardial endothelial cells of Atlantic cod Gadus morhua. J Exp Biol. 1998;201:1707–1718. doi: 10.1242/jeb.201.11.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Speilberg L, Evensen O, Nafstad P. Liver of juvenile Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L.: a light, transmission, and scanning electron microscopic study, with special reference to the sinusoid. Anat Rec. 1994;240:291–307. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092400302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sorensen KK, Tollersrud OK, Evjen G, Smedsrod B. Mannose-receptor-mediated clearance of lysosomal alpha-mannosidase in scavenger endothelium of cod endocardium. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2001;129:615–630. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00300-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dannevig BH, Struksnæs G, Skogh T, Kindberg GM, Berg T. Endocytosis via the scavenger- and the mannose-receptor in rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri) pronephros is carried out by nonphagocytic cells. Fish Physiol Biochem. 1990;8:228–238. doi: 10.1007/BF00004462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karpen SJ. Growing old gracefully: caring for the 90-year-old liver in the 40-year-old transplant recipient. Hepatology. 2010;51:364–365. doi: 10.1002/hep.23447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Minor RK, Allard JS, Younts CM, Ward TM, de Cabo R. Dietary interventions to extend life span and health span based on calorie restriction. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:695–703. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.