Case Report

A 48-year-old woman presented to the clinic with ascending colon carcinoma that had been diagnosed 6 months earlier. The disease had metastasized to the axial and peripheral skeleton in multiple locations. Radiation therapy was administered to the cervical and thoracic spine with 30 fractions of 200 g each. Within 6 weeks of the completion of radiation, the patient developed dysphagia, chest pain, bouts of regurgitation, nausea, and a weight loss of 15 pounds. An esophagogas-troduodenoscopy revealed a tight inflammatory, likely radiation-induced, stricture in the distal esophagus that had narrowed the lumen to 8 mm. The patient underwent balloon dilation of the lumen to 13 mm. She developed chest discomfort in the recovery area, and a hyp-aque esophagogram revealed a perforation (Figure 1). A nasogastric tube was placed endoscopically, and the patient received broad-spectrum antibiotics and intravenous fluids. Within 24 hours, a Polyflex stent (18-mm wide × 9-cm long, with a 23-mm proximal mouth; Boston Scientific) was placed and attached to the proximal esophagus with nylon ligatures and 2 Resolution clips. The patient was able to eat soft solids within 48 hours of the stent's placement and was discharged on the fourth day. She gained weight and reported no chest pain or dysphagia. Chemotherapy was started due to an abnormal positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan and a rising carcinoembryonic antigen level. The stent was removed 6 weeks later. The leak had repaired itself endoscopically, and inflammatory mucosa with an intact lumen was noted with a barium esophagogram (Figure 2).

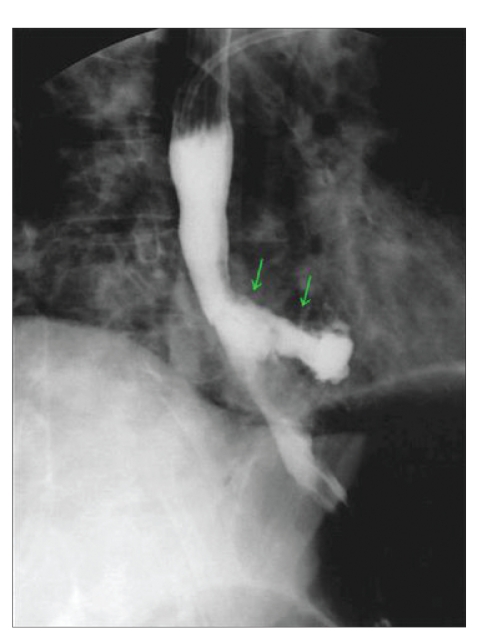

Figure 1.

Barium esophagogram revealing a perforation in the distal esophagus.

Figure 2.

Follow-up esophagogram obtained 1 month after Polyflex stent removal.

Discussion

Esophageal perforation is a life-threatening situation and requires a rapid diagnosis and prompt intervention. Iatrogenic causes account for nearly 75% of cases. Management of the perforation depends upon the site of the leak, the time from the injury to the intervention, and the skill and experience of both the surgeon and endoscopist. Recent conservative approaches have included observation, broad-spectrum antibiotics, radiologic drainage, and total parenteral nutrition as needed. With the advent of self-expanding plastic stents (SEPS), surgical intervention can often be eliminated. Esophageal stents have been part of endoscopic practice for decades, but the plastic, removable Polyflex stent has aided in the treatment of benign and malignant strictures, leaks, and fistulae. The use of this stent early on can prevent mediastinal and pleural space soiling, thereby eliminating the need for urgent surgical drainage, repair, resection, or diversion. Over the past 15 years, self-expanding metal stents (SEMS), made of nitinol or stainless steel, have evolved. These devices should not be used for benign strictures or iatrogenic perforations.1

In recent years, the treatment of benign, inflammatory strictures has taken center stage in the endoscopy community. The use of SEMS for benign esophageal strictures has been problematic in the past. Granulation tissue in-growth, migration, bleeding, and perforation have been described. Woven SEPS with a thin silicone coating are popular. Ease of insertion, the need for minimal preparatory esophageal dilation, and the formation of an occlusive seal within the lumen have been reported with SEPS.2 SEPS have been placed for a variety of postoperative esophagectomy and bariatric surgery leaks,3,4benign strictures,5 perforations following left atrial catheter ablations,6 Boerhaave tears, cervical dissections,7and esophageal fistulae. As with the patient discussed above, esophageal perforation can follow balloon- or wire-guided dilation, particularly in the radiated esophagus. Perforation may also follow endoscopic mucosal resection for neoplastic lesions or Barrett esophagus, as well as surgical fundoplication and myotomy.

The use of SEPS to close an iatrogenic perforation has been described only rarely in the literature as of yet. Polyflex has been used for disruptions following routine esophageal dilation, pneumatic dilation, perforations following transesophageal echo probes during cardiac surgery, or transmediastinal trauma from gunshot wounds. This material has been utilized to treat benign radiation-induced strictures, caustic substance ingestion injuries, peptic lesions, malignant obstruction, anastomotic strictures, and a variety of postsurgical leaks and fistulae.8Repici and colleagues5 described 15 benign strictures that were stented with Polyflex. Four of these strictures were induced by radiation. Temporary placement for a mean of 6 weeks was successful in all 15 patients. In this study, 80% experienced long-term resolution of the stricture, with a follow-up of nearly 2 years. All of these patients had failed repeated esophageal dilations.

In recent years, closure of traumatic, nonmalignant perforations of the esophagus smaller than 50–70% of the circumference has been described with SEPS Polyflex. This stent may be better tolerated in the proximal and distal esophagus, as it can narrow under pressure, is more malleable than SEMS, and appears to cause less tissue inflammation and proliferation at the mucosal level.

In addition to hemostatic clips, acrylic glues, and argon plasma coagulation, both SEMS and SEPS have been utilized to close a variety of leaks, fistulae, and large-caliber perforations.9-12 Polyflex stents have been shown to occlude perforations quickly, thus allowing the patient to commence oral nutritional intake, which shortens hospital stays, avoids costly and morbid surgical interventions, and results in a large healthcare cost savings. The material of the stent provides balanced radial force and adapts elastically to the native esopha-geal wall.9 Radio-opaque markers in the proximal, mid-, and distal esophagus allow for easy deployment either under direct vision or with fluoroscopic assistance. The stent can easily be removed with a rat-tooth forceps or a snare once healing has been completed (as determined by endoscopy, contrast studies, or cross-sectional imaging).10 Migration rates in inoperable strictures with this stent range from 6% to 18% but can easily be managed endoscopically with removal, replacement, or manipulation and repositioning.11 Migration of SEPS (in up to 30% of cases in the literature) can be minimized by oversizing the length by at least 4 cm and, as described in the patient above, attaching the proximal mouth to the esophageal wall with ligatures and hemostatic clips.

Summary

Esophageal perforation is a significant risk with dilation of previously irradiated esophagus. Prompt detection of the perforation is vital. Treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics, continuous acid suppression, nasogastric suction, and consideration of prompt placement of a SEPS may avoid surgical intervention. The Polyflex stent has been shown to be safe, easy to deploy, efficacious, and cost-effective for an iatrogenic esophageal perforation. SEPS should be placed for a minimum of 4–6 weeks and can be removed with a forceps or a snare once the sealing of the leak is confirmed. To avoid migration, it is suggested that the SEPS Polyflex stent be attached to the esophagus at its proximal opening via ligatures and hemostatic clips.

Dr. Petersen has no disclosures or conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Papachristou GI, Baron TH. Use of stents in benign and malignant esophageal disease. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2007;7:74–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman RK, Ascioti AJ, Wozniak TC. Postoperative esophageal leak management with the Polyflex esophageal stent. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:333–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gelbmann CM, Ratiu NL, Rath HC, et al. Use of self-expandable plastic stents for the treatment of esophageal perforations and symptomatic anastomotic leaks. Endoscopy. 2004;36:695–699. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-825656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukumoto R, Orlina J, McGinty J, Teixeira J. Use of Polyflex stents in treatment of acute esophageal and gastric leaks after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Repici A, Conio M, De Angelis C, et al. Temporary placement of an expandable polyester silicone-covered stent for treatment of refractory benign esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:513–519. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01882-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bunch TJ, Nelson J, Foley T, et al. Temporary esophageal stenting allows healing of esophageal perforations following atrial fibrillation ablation procedures. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:435–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buscaglia JM, Sherwood JT, Jagannath SB. Endoscopic treatment of a cervical esophageal dissection using a Polyflex self-expanding plastic stent. Pract Gastroen-terol. 2007;31:68–71. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiev J, Amendola M, Bouhaidar D, Sandhu BS, Zhao X, Maher J. A management algorithm for esophageal perforation. Am J Surg. 2007;194:103–106. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langer FB, Wenzl E, Prager G, et al. Management of postoperative esopha-geal leaks with the Polyflex self-expanding covered plastic stent. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schubert D, Scheidbach H, Kuhn R, et al. Endoscopic treatment of thoracic esophageal anastomotic leaks by using silicone-covered, self-expanding polyester stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:891–896. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costamagna G, Shah SK, Tringali A, Mutignani M, Perri V, Riccioni ME. Prospective evaluation of a new self-expanding plastic stent for inoperable esophageal strictures. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:891–895. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-9098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hünerbein M, Stroszczynski C, Moesta KT, Schlag PM. Treatment of thoracicanastomotic leaks after esophagectomy with self-expanding plastic stents. AnnSurg. 2004;240:801–807. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000143122.76666.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]