Abstract

Cultivation of primary hepatocytes as spheroids creates an efficient three-dimensional model system for hepatic studies in vitro and as a cell source for a spheroid reservoir bioartificial liver. The mechanism of spheroid formation is poorly understood, as is an explanation for why normal, anchorage-dependent hepatocytes remain viable and do not undergo detachment-induced apoptosis, known as anoikis, when placed in suspension spheroid culture. The purpose of this study was to investigate the role of E-cadherin, a calcium-dependent cell adhesion molecule, in the formation and maintenance of hepatocyte spheroids. Hepatocyte spheroids were formed by a novel rocker technique and cultured in suspension for up to 24 h. The dependence of spheroid formation on E-cadherin and calcium was established using an E-cadherin blocking antibody and a calcium chelator. We found that inhibiting E-cadherin prevented cell–cell attachment and spheroid formation, and, surprisingly, E-cadherin inhibition led to hepatocyte death through a caspase-independent mechanism. In conclusion, E-cadherin is required for hepatocyte spheroid formation and may be responsible for protecting hepatocytes from a novel form of caspase-independent cell death.

Keywords: Hepatocyte spheroids, E-Cadherin, Anoikis, Caspase-independent cell death

INTRODUCTION

We have previously shown that spheroids of primary (nontransformed) rat hepatocytes can be formed rapidly and efficiently using a rocked suspension technique (2). Under these conditions, freshly isolated rat hepatocytes aggregate spontaneously to form spheroids of 60–120 μm diameter by 24 h and viability exceeding 95%. As previously shown by others (1), differentiated hepatocyte functions were better maintained in spheroid culture. However, cell loss became problematic over extended culturing periods. While culturing hepatocytes in anchorage-independent conditions has many advantages, little is known about how this cell loss occurred over time. Anchorage-independent spheroid cell cultures, such as our novel rocked culturing technique (13), rely upon calcium-dependent cell–cell adhesions for survival and function, which occur in the absence of an extracellular matrix. An apoptotic mechanism of cell death occurs when cells lose their attachment from the extracellular matrix or other cells is known as anoikis (4,7,18). E-Cadherin, a calcium-dependent transmembrane protein that binds homophilically to other E-cadherin molecules on adjacent cells, is therefore a likely candidate required for spheroid formation and maintenance.

E-Cadherin, one of the most important and well-studied cell adhesion proteins, is a known factor involved in anoikis (5). The loss of E-cadherin adhesions has been implicated in the induction of anoikis in tumorigenic epithelial cells (6) and during the normal shedding of the intestinal epithelial cells at the villus tip (3). Therefore, we asked whether E-cadherin was required for spheroid formation and as a necessary step to protect hepatocytes from anoikis cell death. Our findings suggest that E-cadherin was required both for spheroid formation and the protection of hepatocytes from cell death under anchorage-independent rocked spheroid conditions. In contrast to previous studies, our results suggest that cell death can occur via a caspase-independent mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals were housed in the Mayo Clinic vivarium and provided ad lib access to water and standard chow. All animal procedures were performed under the guidelines set forth by the Mayo Foundation Animal Care and Use Committee and are in accordance with those set forth by the National Institutes of Health.

Rat Hepatocyte Isolation

Hepatocytes were isolated from male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) by a two-step perfusion method as previously described (16). All harvests yielded hepatocytes with viability exceeding 90% as determined by trypan blue dye exclusion.

Spheroid Cultures and Conditions

Freshly isolated hepatocytes were suspended in culture medium [William's-E medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Mediatech, Inc.), 10 U/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 10 μg/ml insulin, 5.5 μg/ml transferrin, 5 ng/ml sodium selenite] at a concentration 1 × 106 viable cells/ml. Suspended hepatocytes were inoculated into spheroid dishes (10 × 8 × 2 cm) custom made with glass and siliconized with Sigmacote (Sigma). Spheroid dishes were placed in the incubator and rocked continuously at 0.25 Hz frequency to induce spheroid formation and maintain suspension of spheroids. All culture conditions were maintained in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. Freshly isolated hepatocytes were cultured for 24 h under control conditions, 200 mg/ml mouse IgG1 (2C11) (Santa Cruz), 10 μM Q-Val-Asp-OPh (QVD-OPH) (MP Biochemicals), 10 mM l-carnitine hydrochloride (Sigma), or E-cadherin inhibitory conditions using either 2.5 mM ethylene glycol tetra-acetic acid (EGTA) or 10 μg/ml E-cadherin inhibitory antibody (Santa Cruz). Spheroids of hepatocytes were sampled at 6, 12, and 24 h.

Morphometrics of Hepatocyte Spheroid Formation

Representative 1-ml samples were removed from spheroid dishes to determine spheroid diameter using a Multisizer 3 (560 μm aperture; Beckman Coulter).

Electron Microscopy

Spheroids were examined by transmission electron microscopy. Briefly, samples of spheroids were preserved in Trump's fixative (1% glutaraldehyde and 4% formaldehyde in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer, pH 7.2) and sectioned by the Electron Microscopy Core Facility (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). Sections (90 nm) were placed on 200-nm mesh copper grids and stained with lead citrate. Micrographs were taken with a JEOL 1200 EXII electron microscope operating at 60 kV.

Cell Death Analyses

Hepatocytes were sampled from rocking culture conditions and either fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde or assessed for caspase activity using the Apo-ONE Homogenous Caspase-3/7 Assay (Promega), as per manufacturer's instructions. Fixed cells were embedded as a fibrin clot in paraffin and 4-μm sections were transferred to glass slides. Tissue sections were dewaxed and stained either with hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E) or by terminal deoxynucleotidyl-transferase (TdT)-mediated biotinylated (dUTP) nick-end labeling (TUNEL). TUNEL staining was performed using a commercially available in situ apoptosis detection kit (Roche Diagnostics), as per manufacturer's instruction. Tissue samples were analyzed by epifluorescence microcopy (Axioscope, Carl Zeiss Inc.) configured for fluorescein and 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). DAPI counterstaining was utilized to assess nuclear morphology of cells positive by TUNEL staining (green nuclei). Percent cell death was determined from the ratio: (TUNEL positive nuclei/DAPI positive nuclei) × 100%.

Western Blot Analyses

Protein extracts were prepared using standard techniques. The extracts were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with 1:1000 dilution of rat anti-caspase-3 polyclonal antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology) or 1:500 dilution of goat anti-actin polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.). Immunoblots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK) after incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary goat anti-rat IgG or donkey anti-goat IgG antibodies (Biosource International).

Statistical Methods

Results are expressed as mean values ± SEM. Statistical significance between different culture conditions was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction of pairwise comparisons.

RESULTS

E-Cadherin Is Required for Spheroid Formation

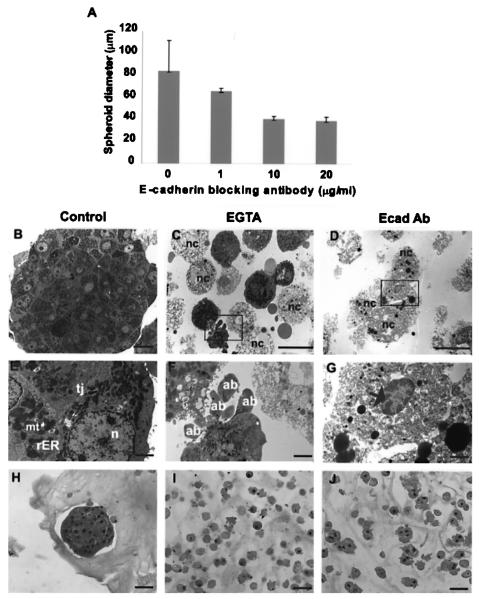

To evaluate the role of E-cadherin in spheroid formation of isolated primary rat hepatocytes we inhibited the ability of E-cadherin to form homodimers among adjacent hepatocytes either by using 2.5 mM EGTA to remove extracellular calcium or by adding an E-cadherin-inhibiting antibody (Fig. 1A). All observations were made during the initial 24 h of hepatocyte culture and spheroid formation.

Figure 1.

Effect of E-cadherin inhibition on hepatocyte spheroid formation. (A) Coulter data shows a significant reduction in average spheroid diameter of hepatocytes formed under control (anti-mouse IgG) compared to E-cadherin blocking antibody treatment at 1, 10, and 20 μg/ml after 24 h of rocked suspension culture (p < 0.0001). Representative transmission electron micrographs (B–G) and H&E light micrographs (H–J) of primary rat hepatocytes after 24 h of rocked suspension culture under either control (B, E, H), 2.5 mM EGTA (C, F, I), or 10 μg/ml E-cadherin-inhibiting antibody (Ecad Ab) (D, G, J) treatment. (F) and (G) are insets of (C) and (D), respectively. Control treated spheroids contained adherent healthy hepatocytes as indicated by the presence of tight junctions (tj), rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER), mitochondria (mt), euchromatic nuclei (n). In contrast, E-cadherin-inhibited hepatocytes did not form spheroids and appeared either necrotic (nc) with condensed peripheral chromatin (black arrow) or apoptotic, as indicated by the presence of apoptotic bodies (ab). Scale bars: 20 μm (B–D), 2 μm (E–G), and 50 μm (H–J) length.

We first observed that spheroid diameter decreased in the presence of increasing amounts of E-cadherin inhibiting antibody (Fig. 1A). The maximum inhibitory effect was observed at 10 μg/ml of E-cadherin-inhibiting antibody. To determine whether reduced spheroid diameter was a result of cell death, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed to identify ultrastructural changes indicative of apoptosis (Fig. 1B–G). Figure 1B shows the ultrastructure of a control spheroid (IgG treated) after 24 h. Day 1 control spheroids had tight aggregated spherical morphology with tight junctions between adjacent cells (Fig. 1E). Cells within a spheroid exhibited distinct nuclei (n) with peripherally localized euchromatic chromatin, abundant mitochondria, and rough endoplasmic reticulum. E-cadherin-inhibited hepatocytes had distinct cell death morphologies as indicated by the presence of apoptotic bodies (Fig. 1F) and necrotic cells (Fig. 1G). In summary, spheroid formation appeared to depend on the number of E-cadherin binding sites available for cell–cell adhesions. Cultures with the lowest number of hepatocytes incorporated into spheroids correspond to those with the greatest inhibition of E-cadherin.

Loss of E-Cadherin Caused Cell Death of Primary Rat Hepatocyte Spheroid Cultures

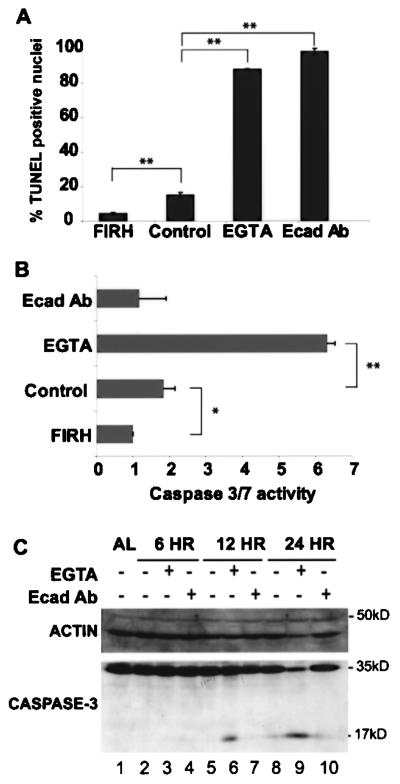

Maximal inhibition of E-cadherin caused massive cell death and marked inhibition of spheroid formation in rocked culture. To verify whether DNA fragmentation, indicative of anoikis, was present within the E-cadherin-inhibited cultures we performed TUNEL analyses on paraffin sections of spheroids. Figure 2A shows that 17% of hepatocytes were TUNEL positive under control conditions, whereas >90% of hepatocytes were TUNEL positive by 24 h of E-cadherin inhibition (p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Characterization of cell death triggered by E-cadherin inhibition. Cell death in hepatocyte spheroids was determined by quantification of the percentage of TUNEL-positive nuclei and caspase-3/7 activity after 24 h in culture. Freshly isolated rat hepatocytes (FIRH) were cultured under control (anti-mouse IgG) or E-cadherin inhibitory conditions: either with calcium depletion using 2.5 mM EGTA or E-cadherin blocking antibody at 10 μg/ml (Ecad Ab). (A) TUNEL-positive nuclei were observed in 5% of freshly isolated rat heptocytes (FIRH). After 24 h of rocked suspension culture, TUNEL-positive nuclei were observed in 12% of cells under control conditions, whereas EGTA and E-cad Ab treatment resulted in 85% and 98% TUNEL-positive nuclei. All comparisons to control conditions were highly significant (**p < 0.0001). The percentage of TUNEL-positive nuclei was quantified by dividing the total number of TUNEL-positive nuclei by the number of DAPI stained nuclei. Mean values represent counts ± SEM obtained from three independent experiments. (B) Caspase-3/7 activity was highest in EGTA cultures and lowest in FIRH. A significant difference in caspase-3/7 activity was observed between control conditions and both EGTA conditions and FIRH (*p < 0.017, **p < 0.0001). Error bars represent the SEM of at least three independent experiments. (C) Representative Western blot analysis detecting caspase-3 using 100 mg protein lysate derived from either adult rat liver (AL) or primary rat hepatocytes harvested after 6, 12, and 24 h of rocked suspension culture. Caspase-3 was detected in both the inactive (32 kDa) and active (18 kDa) form of caspase-3. Active caspase-3 protein was only detected in EGTA-treated cultures at the 12- and 24-h time points.

It is known that blocking E-cadherin adhesions can lead to cleavage and activation of caspase-3, a necessary step for cleavage of nuclear proteins essential for DNA fragmentation and chromatin marginalization associated with anoikis. To determine if this effector caspase was activated under EGTA, anti-E-cadherin and control conditions, combined caspase-3 and caspase-7 activities were measured (Fig. 2B) and the presence of the active form of caspase-3 was identified by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2C). Results show that EGTA treatment induced the greatest level of caspase activation, while no additional caspase activity was induced in cultures treated with anti-E-cadherin antibody compared to control conditions (Fig. 2B). To determine when caspase-3 cleavage products were present in greater amounts in EGTA-treated cultures compared to control or anti-E-cadherin antibody conditions, Western blot analysis was performed on total protein lysates obtained at 6, 12, and 24 h (Fig. 2C). Active caspase-3 protein was only detected in EGTA-treated cultures at 12 and 24 h. Cell death due to E-cadherin blocking antibody treatment did not involve a caspase-3/7-activated downstream mechanism.

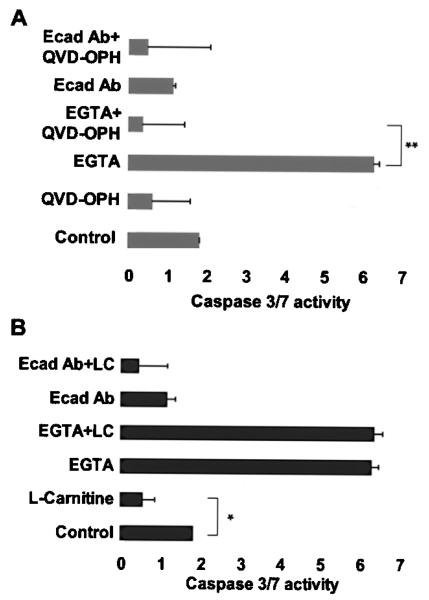

Cell Death Was Independent of Caspase Activity and Inconsistent With an Anoikis Mechanism

Cultures were next treated with a general pan-caspase inhibitor, QVD-OPH, to determine whether any caspase activity was necessary for DNA fragmentation, as determined by the presence of TUNEL-positive nuclei, and subsequent cell death after direct E-cadherin inhibition (Fig. 3A). Medium was also supplemented with l-carnitine, a known mitochondrial membrane permeability stabilizer (14), to test whether cell death involved a loss of mitochondrial matrix permeability (MMP) after inhibition of E-cadherin adhesions (Fig. 3B). Using Coulter measurements we first observed that spheroid diameter was not affected by l-carnitine treatment (data not shown). Also, the addition of L-carnitine had no effect on the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells with or without E-cadherin inhibition (data not shown). These results suggest that cell death in EGTA-treated cultures was due to activation of caspases independent of changes in MMP. In contrast, cell death was independent of caspase activation or changes in MMP in cultures where E-cadherin was inhibited directly by an anti-E-cadherin antibody. These results suggest that the loss of cell–cell anchorages by anti-E-cadherin antibodies results in both a caspase-independent mechanism of cell death that could not be reversed through stabilization of MMP.

Figure 3.

Effect of caspase or MMP inhibition on rat hepatocyte spheroid formation. Isolated primary rat hepatocytes were cultured under rocked suspension conditions using control (anti-mouse IgG), 2.5 mM EGTA, or E-cadherin blocking antibody (Ecad Ab) ± (A) the pan-caspase inhibitor, QVD-OPH (10 μM) or (B) the mitochondrial membrane permeability stabilizer, l-carnitine (LC) (10 mM). Caspase-3/7 activity was significantly lower in EGTA + QVD-treated cultures compared to EGTA treatment alone (**p < 0.0001). Caspase-3/7 activity was not reduced significantly in Ecad Ab + QVD-OPH treated cultures compared to Ecad Ab treatment alone. l-Carnitine treatment had a significant effect only when compared to control conditions (p = 0.0011), but did not change significantly in EGTA or Ecad Ab conditions ± LC. Error bars represent the SEM from three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

E-Cadherin attachment at cell–cell contacts has a known function in the suppression of anoikis. We observed a dose-dependent response to spheroid formation. When E-cadherin engagement was blocked, spheroid formation was abrogated; this resulted in cell death by a mechanism independent of caspase activation. We have previously shown that E-cadherin is present along the basolateral membrane between rat hepatocytes in spheroids formed by rocked technique at 24 h, but by 48 h confocal images of E-cadherin staining demonstrated more E-cadherin intracellularly (2). The intracellular staining of E-cadherin suggested to us that reduced E-cadherin interactions on the hepatocyte surface may be responsible for increased cell loss observed in long-term spheroid cultures. Nonattachment after cryopreservation of hepatocytes has also been associated with loss of E-cadherin gene expression and protein expression (17). Of note, viability of cryopreserved hepatocytes was improved if they were allowed to form spheroids, and presumably stabilize their cell–cell attachments, before cooling or vitrification (8,12).

Anoikis is thought to be the main mechanism of cell death when cell–matrix and E-cadherin cell–cell interactions are perturbed in primary epithelial cells in vivo (3,11). In the present study, we observed that anoikis, defined as a caspase-3-dependent cell death mechanism, is unlikely the cell death mechanism of anchorage-independent primary cultures of rat hepatocytes; rather, cell death observed due to loss of E-cadherin adhesion is more reminiscent of necrosis. Our findings contrast a prior report using hepatoma spheroid cultures that blocking E-cadherin interactions lead to anoikis (9). The prior report failed to demonstrate that DNA fragmentation was a result of caspase-dependent apoptotic signaling mechanisms. Nonetheless, reconciling the mechanisms between tumorigenic and nontumorigenic cells will be necessary because most immortalized cell lines have already acquired adapted responses that inhibit anoikis. The finding that E-cadherin inhibition causes cell death and DNA fragmentation through a caspase-independent mechanism highlights the need for new approaches to tease out the intracellular mechanisms of cell death affected by changes in cell–matrix and cell–cell adhesions.

Several mechanisms may be responsible for DNA fragmentation observed in dead and dying hepatocytes where E-cadherin junctions are perturbed. First, oncotic necrosis can lead to DNA fragmentation, although the intracellular mechanism that causes this process is poorly understood (15). Second, caspase-independent apoptosis due to excessive autophagy can cause DNA fragmentation (10). We performed additional experiments to test whether the addition of the autophagy inhibitor, 3-methyladenine, could prevent DNA fragmentation and cell death in E-cadherin-inhibited cultures. We did not identify any significant changes in TUNEL-positive cells under any of our culturing conditions with or without 3-methyladenine (data not shown), suggesting that excessive autophagy is unlikely a mechanism of cell death in primary rat hepatocyte spheroids.

In conclusion, we offer a systematic analysis of the influence of E-cadherin on formation and stability of spheroids formed from primary rat hepatocytes. Our study suggests that E-cadherin adhesions do not protect hepatocytes from anoikis. Rather, E-cadherin adhesions protect hepatocytes from a previously unrecognized form of caspase-independent cell death in primary hepatocyte spheroid cultures. Although these findings do not eliminate the possibility that E-cadherin signals prevent an anoikis response, they do add to the growing body of evidence that cadherins provide direct, functionally relevant signaling for epithelial cell survival when extra-cellular matrices are absent, such as those for suspension spheroid cultures. Future studies identifying the mechanism of caspase-independent cell death due to changes in E-cadherin availability at the cell surface would be insightful.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to give our thanks to Frank Secreto, Trace Christensen, and Justin Mott for technical assistance and Ross Dierkhising for statistical support. The work here was supported by NIH-R01-DK56733, Mayo Foundation (L.Y.), and the Norwegian Research Council (G.N.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambrosino G, Basso S, Varotto S, Zadi E, Picardi A, D'Amico D. Isolated hepatocytes versus hepatocyte spheroids: In vitro culture of rat hepatocytes. Cell Transplant. 2005;14(6):397–401. doi: 10.3727/000000005783982954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brophy CM, Luebke-Wheeler JL, Amiot BP, Khan H, Remmel RP, Rinaldo P, Nyberg SL. Rat hepatocyte spheroids formed by rocked technique maintain differentiated hepatocyte gene expression and function. Hepatology. 2009;49(2):578–586. doi: 10.1002/hep.22674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fouquet S, Lugo-Martinez VH, Faussat AM, Renaud F, Cardot P, Chambaz J, Pincon-Raymond M, Thenet S. Early loss of E-cadherin from cell-cell contacts is involved in the onset of anoikis in enterocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279(41):43061–43069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405095200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frisch S, Francis H. Disruption of epithelial cell-matrix interactions induces apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 1994;124:619–626. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grossmann J. Molecular mechanisms of “detachment-induced apoptosis—anoikis”. Apoptosis. 2002;7(3):247–260. doi: 10.1023/a:1015312119693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang HG, Jenabi JM, Zhang J, Keshelava N, Shimada H, May WA, Ng T, Reynolds CP, Triche TJ, Sorensen PH. E-cadherin cell-cell adhesion in ewing tumor cells mediates suppression of anoikis through activation of the ErbB4 tyrosine kinase. Cancer Res. 2007;67(7):3094–3105. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Vandenabeele P, Abrams J, Alnemri ES, Baehrecke EH, Blagosklonny MV, El-Deiry WS, Golstein P, Green DR, et al. Classification of cell death: Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2009. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16(1):3–11. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai P, Meng Q, Sielaff T, Hu W. Hypothermic maintenance of hepatocyte spheroids. Cell Transplant. 2005;14(6):375–389. doi: 10.3727/000000005783982927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin R-Z, Chou L-F. Dynamic analysis of hepatoma spheroid formation: Roles of E-cadherin and beta1-inte-grin. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;324:411–422. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lockshin RA, Zakeri Z. Caspase-independent cell deaths. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2002;14(6):727–733. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00383-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lugo-Martinez VH, Petit CS, Fouquet S, Le Beyec J, Chambaz J, Pincon-Raymond M, Cardot P, Thenet S. Epidermal growth factor receptor is involved in enterocyte anoikis through the dismantling of E-cadherin-mediated junctions. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2009;296(2):G235–244. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90313.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magalhaes R, Wang X, Gouk S, Lee K, Ten C, Yu H, Kuleshova L. Vitrification successfully preserves hepatocyte spheroids. Cell Transplant. 2008;17(7):813–828. doi: 10.3727/096368908786516765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nyberg SL, Hardin J, Amiot B, Argikar UA, Remmel RP, Rinaldo P. Rapid, large-scale formation of porcine hepatocyte spheroids in a novel spheroid reservoir bioartificial liver. Liver Transpl. 2005;11(8):901–910. doi: 10.1002/lt.20446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paz Soldan M, Warrington A, Bieber A, Bogoljub C, Van Keulen V, Pease L, Rodriguez M. Remyelination-promoting antibodies activate distinct Ca+2 influx pathways in astrocytes and oligodendrocytes: Relationship to mechanism of myelin repair. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2003;22:14–24. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(02)00018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulze-Bergkamen H, Schuchmann M, Fleischer B, Galle PR. The role of apoptosis versus oncotic necrosis in liver injury: Facts or faith? J. Hepatol. 2006;44(5):984–993. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seglen P. Preparation of isolated rat liver cells. Methods Cell Biol. 1976;13:29–83. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61797-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terry C, Hughes R, Mitry R, Lehec S, Dhawan A. Cryopreservation-induced nonattachment of human hepatocytes: Role of adhesion molecules. Cell Transplant. 2007;16(6):639–647. doi: 10.3727/000000007783465000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zvibel I, Smets F, Soriano H. Anoikis: Roadblock to cell transplantation? Cell Transplant. 2002;11:621–630. doi: 10.3727/000000002783985404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]