Abstract

Structurally complex and physiologically-active natural products often include bicyclic and polycyclic ring systems having defined relative and absolute configuration. Approaches that allow the construction of more than one carbocyclic ring at a time have proven valuable, in particular those that allow at the same time the control of an array of new stereogenic centers. One of the most general and most widely used protocols has been the intramolecular Diels-Alder [4+2] cycloaddition, in which a single stereogenic center between the diene and the dienophile can control the relative and absolute configuration of the product. We report a two-step [1 + 4 + 1] procedure for bicyclic and polycyclic construction, based on the cyclization of an ω-dienyl ketone. This is complementary to, and will likely be as useful as, the intramolecular Diels-Alder cycloaddition.

Introduction

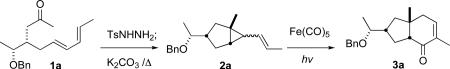

Carbocycles, as exemplified by calcitriol and taxol, can be potent drugs. Although computationally-driven lead generation often suggests potential new drug candidates that are polycarbocyclic, such candidates are usually not pursued, because of the assumption that a carbocyclic drug would be impractical to manufacture.1 We report a simple two-step route (Eq. 1) to the enantiomerically-pure carbobicyclic scaffold 3a from the acyclic ketone 1a (Eq. 1).2

|

(1) |

The construction of carbobicylic 5,6- or 6,6-systems is of great importance in the preparation of structurally complex and biologically intriguing natural products.3 Among those ring forming strategies, intramolecular Diels-Alder (IDA) cycloaddition has received intensive attention for decades because condensation of the dienophile onto the diene directed by a single stereogenic center can generate simultaneously up to four new stereogenic centers in a highly steroselective and often predictable fashion.4 Seeking a complementary protocol, we anticipated that cyclization of an acyclic diene ketone 1a followed by Fe-mediated cyclocarbonylation of the resulting alkenyl cyclopropane 2a could efficiently deliver the bicyclic enone 3a with high diastereocontrol.

There were three concerns with this strategy. The first and most important question was whether we could develop a method for the cyclization of a dienyl ketone such as 1a to the alkenyl cyclopropane 2a. The second question was whether a substituent on the bridge between the ketone and the diene could direct the new stereogenic centers as they formed. The last question was whether Fe-mediated cyclocarbonylation would work with such congested alkenyl cyclopropanes.

Results and Discussion

Novel metal-free synthesis of bicyclic and tricyclic alkenyl cyclopropanes

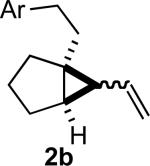

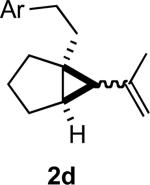

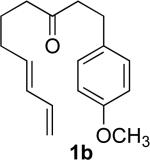

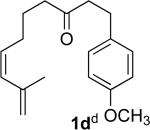

We had reported (Scheme 1) that heating the tosylhydrazone of an ω–alkenyl ketone 4 or aldehyde to reflux in toluene in the presence of K2CO3 delivered the bicyclic diazene 5, and that irradiation of the diazene converted it to the cyclopropane 6.5 In consideration of the high reaction temperature (130 °C), we envisioned that activation of the diazene 7 by an additional alkenyl substituent might enable spontaneous extrusion of N2. The diradical intermediate 8 so generated could cyclize to the alkenyl cyclopropane 2b or to the cyclopentene 9. In order to explore this hypothesis, the diene ketone 1b was exposed to our standard conditions. We were pleased to find that the reaction proceeded smoothly to provide the vinyl cyclopropane 2b directly. Notably, neither the diazene intermediate 7 nor the cyclopentene 9 derived from rearrangement was observed.

Scheme 1.

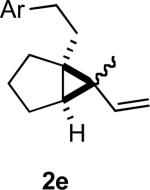

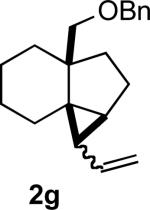

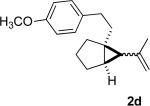

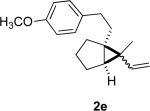

We briefly examined the scope of this cyclization. Alkyl substituents at all positions of the diene were well tolerated. The formation of fused 6,3-system was also successful (Entry 5). Even the ketone 1g cyclized smoothly to the strained tricyclic vinyl cyclopropane 2g (Entry 6). To our knowledge, this is the first direct protocol for the preparation of such alkenyl cyclopropanes.

Fe-mediated cyclocarbonylation

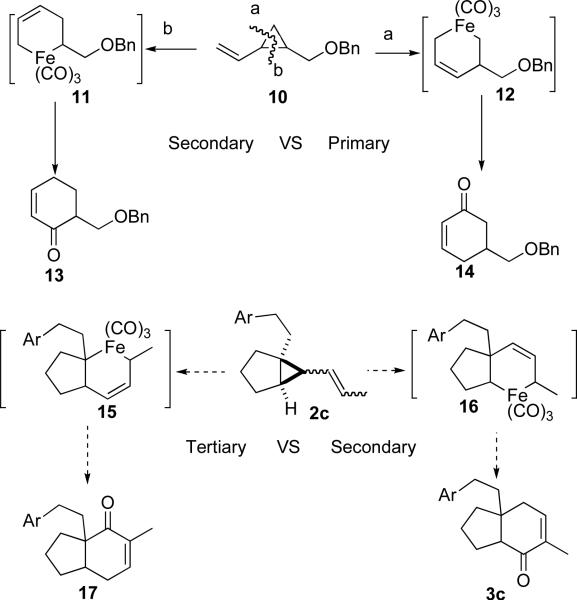

With the bicyclic alkenyl cyclopropanes readily available, we were prepared to explore the Fe-mediated cyclocarbonylation. Previous studies in our laboratory (Scheme 2) showed that the Fe(CO)5-mediated cyclocarbonylation of alkenyl cyclopropanes was a general method for the construction of 5-alkyl cyclohexenones.7 The organometallic cleavage of alkenyl cyclopropane 10 preferentially proceeded via the metallacycle 12, leading to the cyclohexenone 14. In consideration of the complexity of alkenyl cyclopropane 2c, there are still two uncertainties for cyclocarbonylation. The first is whether this cyclocarbonylation would work with the much more sterically-hindered substrate 2c. The other factor to consider is whether the Fe(CO)5-mediated carbonylation of bicyclic alkenyl cyclopropane 2c could follow the same rule to give bicyclic cyclohexenone 3c via metallacycle 16 with a more stable secondary carbon-metal bond, or take a different route to deliver the bicyclic cyclohexenone 17 via a metallacycle 15 with the tertiary carbon-metal bond.

Scheme 2.

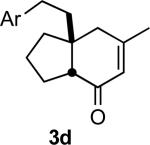

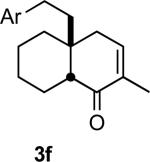

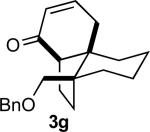

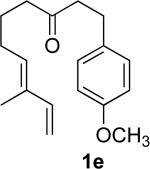

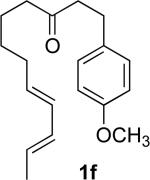

In practice we were pleased to observe that the Fe catalyzed reaction of 2c proceeded smoothly to yield 3c as the sole product. We have made a preliminary investigation (Table 2) of this reaction, which appears to be general. The reaction gave carbobicyclic 5,6-systems with good regiocontrol. Alkyl substituents at all positions of the alkenyl cyclopropane were again well tolerated. The formation of a 6,6-system was also successful (Entry 5). Cyclocarbonylation of 2g even delivered the more complex tricyclic compound 3g (Entry 6). Although in general the product cyclohexenones were conjugated, equilibration of 3e delivered predominantly the nonconjugated enone, as illustrated. We note that Fe(CO)5 is relatively innocuous (LD50 = 25 mg/kg), and certainly inexpensive (three cents/mmol).

Table 2.

Fe-Mediated Cyclocarbonylation

Yields are for pure chromatographed material.

Reactions were run to 52-82% conversion. Yields are based on starting material not recovered.

Diastereocontrol in the Cycloaddition

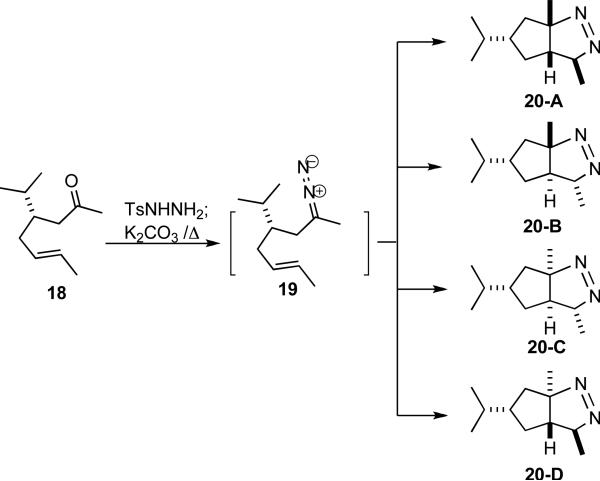

We had earlier observed that the intramolecular dipolar cycloaddition to form the cyclic diazene could proceed with substantial diastereocontrol. To understand the diastereoselectivity of the intramolecular 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of diazoalkanes, computational analysis of the possible transition states (TS) was performed to compare their relative stability. For the calculation, a simplified model structure 18 (Scheme 3) was used. There are four competing transion states (TS-A-D) which lead to four diazene diastereomers (20-A-D). To assess the relative energies of these transition states, we employed B3LYP density functional theory (DFT) calculations, using the 6-31+G(d,p) basis set as implemented in the Gaussian 03 program.8 Computational results indicated that TS-A was more stable by 1.51 kcal/mol compared with its nearest competitor TS-C. Therefore 20-A would be the kinetically favored product. We also observed that for these two more stable TS, the C-C atom distance was about 2.25 Å and the C-N atom distance was about 2.3 Å. The diazo dipole was bent at 142°. These results are similar to those calculated for the intramolecular dipolar cycloaddition of a nitrile oxide.9

Scheme 3.

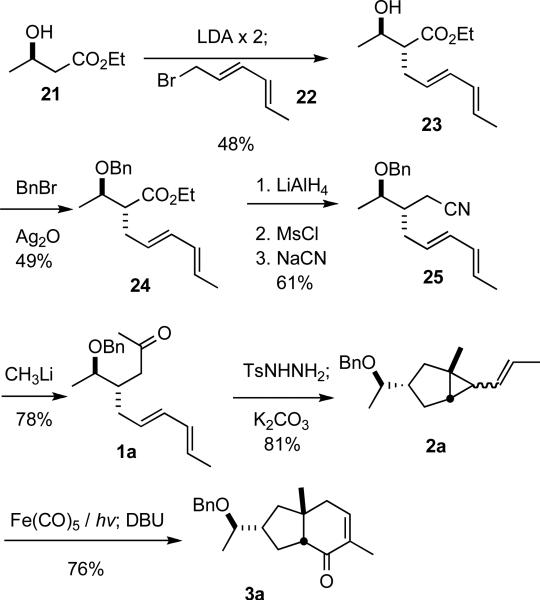

Encouraged by these calculations, we prepared the acyclic ketone 1 a from the commerical enantiomerically-pure ester 21.10 Alkylation of 21 followed by protection of the alcohol provided the ester 24. Reduction followed by mesylation and SN2 substitution gave the nitrile 25. Exposure of the nitrile to methyl lithium completed the assembly of the enantiomerically-pure acyclic substrate 1a. Application of the two-step [1+4+1] protocol delivered 3a as a 6 : 1 mixture of diastereomers. The structure of the major diastereomer, as illustrated, was confirmed by X-ray analysis. These results are consistent with the prediction based on the computationally-based estimate of the differences in energy of the competing transition states for the intramolecular dipolar cycloaddition of 19.

Conclusion

Alkenyl cyclopropanes are versatile building blocks for organic synthesis.11 Their unique structural and electronic properties give rise to an array of interesting and characteristic transformations, which have been extensively developed by several research groups.12 Direct constuction of alkenyl cyclopropanes usually involves metal carbene chemistry.13 Based on the intramolecular 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of an in situ generated diazoalkane, we have uncovered an efficient metal-free synthesis of bicyclic alkenyl cyclopropanes that proceeds with substantial diastereocontrol. The diastereomer preferentially formed was consistent with our computational analysis of the competing transition states. We expect that the same computational approach will make it possible to design other dienyl ketones that will cyclize with high diastereocontrol.

The two-step [1+4+1] protocol for the rapid stereocontrolled assembly of carbobicyclic and carbotricyclic scaffolds outlined here should make such polycyclic intermediates readily available. We expect that this short and environmentally benign protocol will have many applications in target-directed synthesis.

Supplementary Material

Fig. 1.

Calculation of the Transition States

Scheme 4.

Table 1.

Cyclization of ω-Dienyl Ketones

The tosylhydrazone cyclizations were run at 130 °C, unless otherwise noted. For the preparation of the precursor diene iodides, see Ref. 4.

Yields are for pure chromatographed products. The cyclopropanes were ~ 1:1 mixtures of diastereomers.

Yields are based on the starting ketone.

Cyclization was run at 140 °C.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John Dykins for mass spectrometric measurements, supported by the NSF (0541775), Dr. Glenn Yap for the X-ray analysis, and the NIH (GM42056) for financial support. We also thank Professor Douglas J. Doren for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures, details of the X-ray analysis, and 1H and 13C NMR spectra for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.(a) For an overview of synthetic strategies for polycarbocyclic natural products, see Taber DF, Sheth RB, Tian W. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:2433. doi: 10.1021/jo802493k. For more recent examples, see Chandler CL, List B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6737. doi: 10.1021/ja8024164. Surendra K, Corey EJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8865. doi: 10.1021/ja802730a. Trost BM, Ferreira EM, Gutierrez AC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:16176. doi: 10.1021/ja8078835. Pardeshi SG, Ward DE. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:1071. doi: 10.1021/jo7024465. Li L, McDonald R, West FG. Org. Lett. 2008;10:3733. doi: 10.1021/ol8013683. Sethofer SG, Staben ST, Hung OY, Toste FD. Org. Lett. 2008;10:4315. doi: 10.1021/ol801760w. Maity P, Lepore SD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:4196. doi: 10.1021/ja810136m. Chung WK, Lam SK, Lo B, Liu LL, Wong W-T, Chiu P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:4556. doi: 10.1021/ja807566t.

- 2.For a previous example of intramolecular cyclopropanation followed by Fe-mediated cyclocarbonylation, see Ref. 1a.

- 3.a Crimmins MT, Brown BH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004:10264–10266. doi: 10.1021/ja046574b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Vosburg DA, Vanderwal CD, Sorensen EJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002:4552–4553. doi: 10.1021/ja025885o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Taber DF, Nakajima K, Xu M, Rheingold AL. J. Org. Chem. 2002:4501–4504. doi: 10.1021/jo020161g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Johnson TW, Corey EJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001:4475–4479. doi: 10.1021/ja010221k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Boger DL, Ichikawa S, Jiang H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000:12169–12173. [Google Scholar]; f Roush WR, Sciotti RJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998:7411–7419. [Google Scholar]

- 4.a Taber DF, Gunn BP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979:3992. [Google Scholar]; b Taber DF, Saleh SA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980:5085. [Google Scholar]; c Takao K, Munakata R, Tadano K. Chem. Rev. 2005:4779–4807. doi: 10.1021/cr040632u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Craig D. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1987:187–238. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taber DF, Guo P. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:9479. doi: 10.1021/jo8017704. For earlier accounts of this sort of cyclization, see Padwa A, Ku H. J. Org. Chem. 1980;45:3756. Brinker UH, Schrievers T, Xu L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:8609. Ashby EC, Park B, Patil GS, Gadru K, Gurumurthy R. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:424. Jung ME, Huang A. Org. Lett. 2000;2:2659. doi: 10.1021/ol0001517.

- 6.For the preparation of the precursor diene iodides, see Miller CA, Batey RA. Org. Lett. 2004:699. doi: 10.1021/ol0363117. Page PCB, Vahedi H, Batchelor KJ, Hindley SJ, Edgar M, Beswick P. Synlett. 2003:1022. Wang I, Dobson GR, Jones PR. Organometallics. 1990;9:2510. Taber DF, Saleh SA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:5085. Elias CA, Mihou AP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999:4861.

- 7.For the development of Fe-mediated cyclocarbonylation , see: Victor R, Ben-Shoshan R, Sarel S. J. Org. Chem. 1978;43:4971. Taber DF, Kanai K, Jiang Q, Bui G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:6807. Taber DF, Bui G, Chen B. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:3423. doi: 10.1021/jo001737+. Taber DF, Joshi PV, Kanai K. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:2268. doi: 10.1021/jo0302760. Taber DF, Sheth RB. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:8030. doi: 10.1021/jo801767n.

- 8.Frisch MJ, et al. Gaussian 03, Revision B03. Gaussian, Inc.; Pittsburg, PA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee N, Pandit P, Halder S, Patra A, Maiti DK. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:7775–7778. doi: 10.1021/jo801337k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.For the diastereoselective allylation of 21, see Frater G, Muller U, Guunther W. Tetrahedron. 1983;40:1269.

- 11.a Rubin M, Rubina M, Gevorgyan V. Chem. Rev. 2007:3117–3179. doi: 10.1021/cr050988l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Slaun J. Chem. Rev. 2005:396. [Google Scholar]; c Baldwin JE. Chem. Rev. 2003:1197–1212. doi: 10.1021/cr010020z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Sarel S. Acc. Chem. Res. 1978:204–211. [Google Scholar]

- 12.a Trost BM, Shen HC, Horne DB, Toste FD, Steinmetz BG, Koradin C. Chem.-Eur. J. 2005;11:2577. doi: 10.1002/chem.200401065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b de Meijere A, Kurahashi T. Synlett. 2005:2619. [Google Scholar]; c Liu P, Cheong PH, Yu ZX, Wender PA, Houk KN. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008:3939–3941. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Yu ZX, Cheong PH, Liu P, Legault C, Wender PA, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008:2378–2379. doi: 10.1021/ja076444d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Wender PA, Haustedt LO, Lim J, Love JA, Williams TJ, Yoon JY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006:6302–6303. doi: 10.1021/ja058590u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Wegner HA, de Meijere A, Wender PA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005:6530–6531. doi: 10.1021/ja043671w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Wender PA, Gamber GG, Hubbard RD, Pham SM, Zhang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005:2836–2837. doi: 10.1021/ja042728b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Wender PA, Yu Z, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004:9154–9155. doi: 10.1021/ja048739m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Wender PA, Williams TJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:4550–4553. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021202)41:23<4550::AID-ANIE4550>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Wender PA, Barzilay CM, Dyckman AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:179–180. doi: 10.1021/ja0021159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Wender PA, Zhang L. Org. Lett. 2000;2:2323–2326. doi: 10.1021/ol006085q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l Wender PA, Dyckman A. J. Org. Lett. 1999;1:2089–2092. [Google Scholar]; m Wender PA, Fuji M, Husfeld CO, Love JA. Org. Lett. 1999;1:137–139. [Google Scholar]; n Wender PA, Glorius F, Husfeld CO, Langkopf E, Love JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:5348–5349. [Google Scholar]; o Wender PA, Husfeld CO, Langkopf E, Love JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:1940–1941. [Google Scholar]; p Wender PA, Sperandio D. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:4164–4165. [Google Scholar]; q Wender PA, Takahashi H, Witulski B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:4720–4721. [Google Scholar]

- 13.a Barluenga J, Lopez S, Trabanco AA, Fernandez-Acebes A, Florz J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000:8145–8154. [Google Scholar]; b Sarpong R, Su JT, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:13624–13625. doi: 10.1021/ja037587c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.