Abstract

Within its life cycle Eimeria bovis undergoes a long lasting intracellular development into large macromeronts in endothelial cells. Since little is known about the molecular basis of E. bovis-triggered host cell regulation we applied a microarray-based approach to define transcript variation in bovine endothelial cells early after sporozoite invasion (4 h post inoculation (p.i.)), during trophozoite establishment (4 days p.i.), during early parasite proliferation (8 days p.i.) and towards macromeront maturation (14 days p.i.). E. bovis infection led to significant changes in the abundance of many host cell gene transcripts. As infection progressed, the number of regulated genes increased such that 12, 45, 175 and 1184 sequences were modulated at 4 h, 4, 8 and 14 days p.i., respectively. These genes significantly interfered with several host cell functions, networks and canonical pathways, especially those involved in cellular development, cell cycle, cell death, immune response and metabolism. The correlation between stage of infection and the number of regulated genes involved in different aspects of metabolism suggest parasite-derived exploitation of host cell nutrients. The modulation of genes involved in cell cycle arrest and host cell apoptosis corresponds to morphological in vitro findings and underline the importance of these aspects for parasite survival. Nevertheless, the increasing numbers of modulated transcripts associated with immune responses also demonstrate the defensive capacity of the endothelial host cell. Overall, this work reveals a panel of novel candidate genes involved in E. bovis-triggered host cell modulation, providing a valuable tool for future work on this topic.

Keywords: Eimeria bovis, apicomplexan parasite, host cell interaction, transcriptomic, endothelial cell

1. INTRODUCTION

Eimeriosis in cattle is an important enteric protozoan parasitosis which causes economic loss and severe clinical diseases in calves [8, 10]. As with several other pathogenic eimerian species that infect ruminants, the life cycle of Eimeria bovis includes the formation of macromeronts of up to 250 μm in size which develop in endothelial cells [13]. This lengthy process (14–18 days) is associated with the enlargement and reorganisation of the host cell (e.g. host cell cytoskeletal elements [16]). Parasite growth and proliferation within the parasitophorous vacuole (PV) requires nutrients from the host cell, as in other apicomplexa [7, 27]. Furthermore, given that endothelial cells generally represent a highly reactive cell type possessing a broad range of effector mechanisms capable of initiating pathogen elimination, E. bovis has to trigger a complex modulation of the host cell transcriptome and proteome to ensure its successful development. To date few details are known about the molecular mechanisms supporting long term survival of E. bovis or other macromeront forming Eimeria spp. within the host cell. Lang et al. [18] have recently shown that E. bovis prevents host cell apoptosis by up-regulating anti-apoptotic molecules. In avian Eimeria infections, modulation of epithelial host cell apoptosis was also achieved by expression of NFκB and the anti-apoptotic factor bcl-xL [9]. Accordingly, up-regulation of NFκB was observed in sporozoite-infected, non-permissive epithelial host cells [2]. Comparative studies investigating the influence of different apicomplexa on the transcription of genes encoding for immunoregulatory molecules showed a relatively weak impact of E. bovis when compared to Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum infections [30]. Interactions of E. bovis-infected endothelium with leukocytes were shown at the level of PBMC and PMN adhesion and seem to rely on infection-induced up-regulation of distinct adhesion molecules [15, 31].

Taken together, these few reports strongly suggest that E. bovis manipulates the host cell on a broad level involving different functional categories of host cell molecules. In order to gain a broad insight into E. bovis-induced host cell modulation with maximal coverage, we utilised a genome-wide approach using microarrays. We therefore analyzed E. bovis-induced gene regulation in in vitro infected endothelial host cells at distinct time points related to the development of the parasite, i.e., early after invasion by the sporozoite stage, at the trophozoite stage, at the beginning of parasite proliferation and when most mature meronts I were observed. Our microarray-based approach covered 23 000 known genes and uncharacterized expressed sequence tags. We show that with ongoing parasite development the number of regulated host cell gene transcripts increase and that modulated genes significantly interfere with various functions, networks and canonical pathways being mainly involved in cellular development, cell cycle, cell death, host cell immune response and metabolism of the host cell.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Parasite

The E. bovis H strain used in the present study was maintained by passage in Holstein Friesian calves. Sporozoites were excysted from sporulated oocysts as previously described [14] and free sporozoites were collected and suspended at concentrations of 106/mL in complete endothelial cell growth medium (ECGM, PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany).

2.2. Isolation, infection and harvesting of host cells

Bovine umbilical vein endothelial cells (BUVEC) used as host cells were isolated according to Taubert et al. [30]. Confluent BUVEC monolayers established in 75 cm2 culture tissue flasks were infected with 106 E. bovis sporozoites. In order to account for individual variations and to have a rather robust setting, we worked with three different infected BUVEC isolates and respective non-infected BUVEC were analysed in parallel as negative controls. Infected BUVEC were harvested for RNA isolation 4 h, 4, 8 and 14 days post inoculation (p.i.) by direct lysis (1.2 mL lysis buffer/flask, RNeasy Mini Kit, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

2.3. RNA extraction

Total RNA was isolated from BUVEC using the RNeasy-Kit (Qiagen) for isolation of total RNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To minimise contamination with genomic DNA and to achieve reliable photometric measurements of the RNA, an on-column DNase I treatment (Qiagen) was applied during total RNA isolation following the manufacturer’s instructions. The integrity of RNA was controlled by electrophoresis on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel. Since on-column DNase I treatment was not absolutely efficient, the extracted total RNA (1 μg) was additionally treated with RNase-free DNase I (0.5 μg DNase I/μg RNA, Fermentas, 15 min, room temperature). DNase I was inactivated afterwards by heating (65 °C, 10 min). Total RNA samples were then purified using the RNA cleanup protocol (RNeasy Mini Kit) and stored at −80 °C until further use.

2.4. Microarrays

BUVEC expression pattern at the respective harvest time points were assessed using Affymetrix GeneChip bovine Genome Arrays (Affymetrix, High Wycombe, UK) representing 24 016 probe sets or genes that cover 16 813 transcripts annotated to NCBI’s database Entrez Gene. Preparation of antisense biotinylated RNA targets from 5 μg of total RNA was done using the GeneChip Expression 3′Amplification On-Cycle Target Labelling and Control Reagents (Affymetrix) that involve 1st and 2nd strand cDNA synthesis and simultaneous in-vitro transcription and biotin labeling. Microarray hybridisation, washing and subsequent scanning were performed using an Affymetrix hybridisation oven, fluidic station and scanner respectively. The quality of hybridisation was assessed in all samples according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Data were analysed with Affymetrix GCOS 1.1.1 software using global scaling to a target signal of 500. Data were then imported into Arrays Assist software (Stratagene, Madrid, Spain) for subsequent analysis. The data were processed with MAS5.0 to generate cell intensity files (present or absent)1. Quantitative expression levels of transcripts were estimated using PLIER2 for normalisation. Paired t-tests were done between the samples of the two treatment groups within the respective sampling times with three biological replicates. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

2.5. Identification of significantly over-represented host cellular functions, networks and canonical pathways

Individual, time-point-related lists of genes found to be significantly (p ≤ 0.05) up- or down-regulated in E. bovis-infected BUVEC were submitted to Ingenuity Pathway Analyses (IPA; Ingenuity® Systems, Redwood City, CA, USA). Ingenuity maps gene IDs to its database and performs statistical computing to identify the most significant related functions, networks and canonical pathways over-represented in a given list when compared to the Ingenuity Pathways Knowledge Base which relies on millions of individually-modelled, peer reviewed pathway relationships. By default p ≤ 0.05 was used in all calculations. IPA computes a score for each network according to the fit of the network to the set of genes in question. The score is derived from a p-value and indicates the likelihood of focussed genes in a network being found together because of random chance. Gene symbols were coloured according to the respective regulatory state (red indicating up- and green down-regulation).

3. RESULTS

3.1. E. bovis in vitro infection

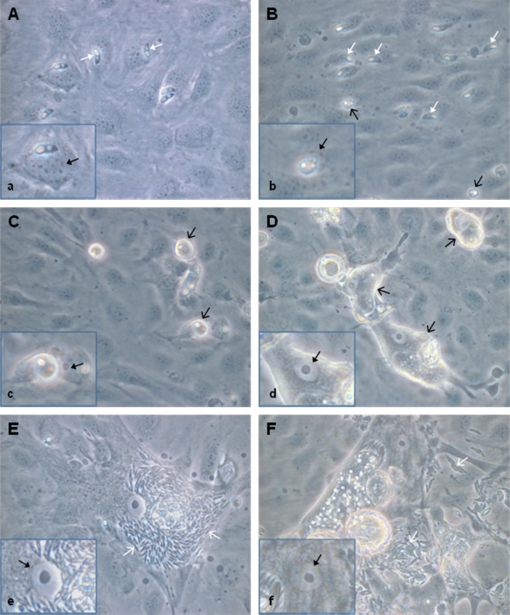

In general, in vitro development of E. bovis corresponded to that described by Hermosilla et al. [14]. Infections of BUVEC with E. bovis sporozoites resulted in initial infection rates of 21.4 ± 5% (1 day p.i.). Infection controls conducted for up to 21 days p.i. revealed successful completion of meront I maturation and the production of merozoites I from days 17 p.i. onwards (Figs. 1E, 1F). On day 14 p.i. 7.1 ± 2.8% of BUVEC carried meronts I; intracellular sporozoites that had not undergone further development were detected in 6.9 ± 4.5% of the cells. However, some microscopic observations were noteworthy as they may directly be linked to the microarray results: immediately after invasion, intracellular sporozoites are generally situated close to the nucleus (Fig. 1A) which may indicate a direct influence on this organelle. Up to 4–7 days p.i., the nucleus of infected cells resembled that of non-infected cells showing a spotted content (Fig. 1B). From day 8 p.i. onwards, the morphology of the nucleus changed, resulting in a “fried-egg”-phenotype with increased proportions of light-coloured euchromatin and large coalescing/growing nucleoli (Figs. 1C–1F). This shape persisted until the release of merozoites I.

Figure 1.

E. bovis in vitro culture used for microarray analyses. Bovine endothelial cells were infected with E. bovis sporozoites. Parasite development was followed microscopically, illustrated here at 4 h (A), 4 (B), 8 (C), 14 (D), 17 (E) and 20 (F) days after infection. Note the enormous enlargement of the host cells (D–F) and the change in nucleus morphology (a–f) in infected cells into a “fried egg”-type. White solid arrow = intracellular sporozoite; black opened arrow = trophozoite (4 days p.i.), immature meront I (8 and 14 days p.i.); white opened arrow = merozoite I; black solid arrow = nucleus of infected cell (all 630× magnification). (A color figure is available at www.vetres.org.)

3.2. E. bovis-induced overall changes in host cell gene transcription

In general, the number of regulated genes increased with ongoing development of the parasite. Microarray analyses revealed a total of 12, 45, 175 and 1184 significantly ≥ 1.5-fold parasite-modulated host cell gene transcripts at the sampled time points (selected data in Tab. I). The proportion of up- and down-regulated gene transcripts varied with time after infection. The ten most modulated gene transcripts were all up-regulated and detected at 14 days p.i.

Table I.

Host cell gene transcription significantly modulated by E. bovis infection (selected).

| Functional class | Symbol | Gene | Fold change in transcription* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 h | 4 d | 8 d | 14 d | |||

| Transcription/Translation | FOS | v-fos FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog | 2.45 | 1.69 | 1.97 | 1.82 |

| KLF4 | Kruppel-like factor 4 | – | – | 2.21 | 2.14 | |

| KLF5 | Kruppel-like factor 5 | – | – | 1.51 | 2.60 | |

| NR2F1 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 2, gr F, member 1 | – | – | −1.69 | −2.55 | |

| PRICKLE1 | Prickle homolog 1 | – | – | 2.05 | 2.97 | |

| FHL2 | Four and a half LIM domains 2 | – | – | 1.98 | 3.88 | |

| CAMTA1 | Calmodulin binding transcription activator 1 | – | – | – | −2.74 | |

| CRYM | Crystallin, mu | – | – | – | 4.12 | |

| EIF4E | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E | – | – | 2.12 | 1.65 | |

| MRPS6 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein S6 | – | – | – | 3.46 | |

| PPARG | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma | – | – | – | −2.77 | |

| Signal transduction | RND1 | Rho family GTPase 1 | – | – | 2.28 | 2.34 |

| SOCS1 | Suppressor of cytokine signaling | – | – | 2.21 | 3.24 | |

| DKK3 | Dickkopf homolog 3 | – | – | 1.73 | 3.96 | |

| STK38L | Serine/threonine kinase 38 like | – | – | 1.69 | 3.05 | |

| PPP1R1B | Protein phosphatase 1, regulatory subunit 1B | – | – | −2.14 | −5.31 | |

| PTGER4 | prostaglandin E receptor 4 | – | – | −1.76 | −5.31 | |

| RASD1 | dexamethasone-induced ras-related protein 1 | – | – | −1.61 | −3.05 | |

| FGL1 | Fibrinogen-like 1 | – | – | – | −4.49 | |

| GPR116 | G protein-coupled receptor 116 | – | – | – | −2.65 | |

| LGR4 | Leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 4 | – | – | – | −2.65 | |

| ARHGEF11 | Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor 11 | – | – | – | 2.98 | |

| APLP2 | Amyloid beta (A4) precursor-like protein 2 | – | – | – | 2.60 | |

| PTPN1 | protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 1 | – | – | – | 4.22 | |

| RAB26 | Ras-related oncogene protein | – | – | – | 2.77 | |

| RASGEF1B | RasGEF domain family, member 1B | – | – | – | −2.65 | |

| RUVBL1 | RuvB-like protein 1 | – | – | – | 2.56 | |

| CHP | Calcineurin homologous protein | – | – | – | 2.77 | |

| SPARCL1 | SPARC-like 1 | – | – | – | −2.65 | |

| Nuclear protein | HIST2H2BE | Histone cluster 2, H2BE | – | 2.13 | 2.13 | 2.82 |

| SNRNP25 | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein 25kDa | – | – | – | 2.71 | |

| Metabolism | ||||||

| Lipids | CYP51 | Cytochrome P450, family 51 | – | – | – | 3.59 |

| CH25H | Cholesterol 25-hydroxylase | – | – | 2.26 | 3.14 | |

| OLR1 | Oxidized low density lipoprotein receptor 1 | – | – | 2.14 | 2.72 | |

| ELOVL5 | Elongation of long chain fatty acids member 5 | – | – | 1.73 | 2.64 | |

| ELOVL6 | Elongation of long chain fatty acids member 6 | – | – | – | 2.85 | |

| NAMPT | Nicotinamide phosphoribosyl-transferase | – | – | 1.50 | 2.60 | |

| ACOT7 | Acyl-Coenzyme A thioesterase 7 | – | – | 1.57 | 4.46 | |

| IDI1 | Isopentenyl-diphosphate delta isomerase 1 | – | – | – | 7.74 | |

| SCD | Stearoyl-Coenzyme A desaturase | – | – | – | 5.26 | |

| HMGCS1 | Hydroxy-methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A synthase 1 | – | – | – | 3.51 | |

| ACAT2 | Acetyl-Coenzyme A acetyltransferase 2 | – | – | – | 2.99 | |

| FASN | Fatty acid synthase | – | – | – | 2.68 | |

| FADS1 | Fatty acid desaturase 1 | – | – | – | 3.42 | |

| FDPS | Farnesyl diphosphate synthase | – | – | – | 2.68 | |

| FABP | Fatty acid binding protein 3 | – | – | – | 3.60 | |

| PLD1 | Phospholipase D1 | – | – | – | −2.66 | |

| NSDHL | NAD(P) dependent steroid dehydrogenase-like | – | – | – | 2.69 | |

| ACER3 | Alkaline ceramidase 3 | – | – | – | 2.62 | |

| Carbohydrates | GALT | Galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase | – | – | 1.53 | 3.17 |

| STBD1 | Starch binding domain 1 | – | – | 2.11 | 4.35 | |

| CHPF | Chondroitin polymerizing factor | – | – | – | 4.80 | |

| SULF2 | Sulfatase 2 | – | – | – | 3.20 | |

| UGGT2 | UDP-glucose glycoprotein glucosyltransferase 2 | – | – | – | 3.17 | |

| EXT1 | Exostoses (multiple) 1 | – | – | – | 2.51 | |

| MTHFD1L | Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase (NADP+ dependent) 1-like | – | 1.63 | 2.87 | 10.78 | |

| MTHFD2 | Methenyltetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase | – | – | 2.05 | 3.06 | |

| Proteins | CYP1A1 | Cytochrom p450 1A1 | 6.35 | – | – | – |

| PSAT1 | Phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 | – | −1.52 | 1.93 | 2.96 | |

| PSPH | Phosphoserine phosphatase | – | −1.50 | 1.69 | 3.33 | |

| GOT1 | Glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase 1 | – | – | – | 3.79 | |

| GPT2 | Glutamic pyruvate transaminase 2 | – | – | – | 2.89 | |

| WDYHV1 | WDYHV motif containing 1 | – | – | – | 2.93 | |

| Nucleic acids | UPP1 | Uridine phosphorylase 1 | – | – | 2.24 | 2.94 |

| CTPS | Cytidine 5′-triphosphate synthetase | – | – | – | 3.63 | |

| RRM2 | Ribonucleotide reductase M2 polypeptide | – | – | 1.83 | 6.70 | |

| Energy production | ME1 | Malic enzyme 1, NADP(+)-dependent, cytosolic | – | – | – | 3.19 |

| MDH1 | Malate dehydrogenase 1 | – | – | – | 2.53 | |

| Other | KCNK1 | Potassium channel, subfamily K, member 1 | – | 1.85 | 2.37 | 3.22 |

| TMEM98 | Transmembrane protein 98 | – | 1.67 | 2.33 | 2.74 | |

| SFXN1 | Sideroflexin 1 | – | – | – | 3.78 | |

| Transport | SLC25A33 | Solute carrier family 25, member 33 | – | – | 1.62 | 2.84 |

| SLC31A1 | Solute carrier family 31, member 1 | – | – | 1.91 | 6.50 | |

| SLC25A4 | Solute carrier family 25, member 4 | – | – | – | 3.33 | |

| SLC2A3 | Solute carrier family 2, member 3 | – | – | – | 3.35 | |

| TINAGL1 | Tubulointerstitial nephritis antigen-like 1 | – | – | – | 3.51 | |

| TFRC | Transferrin receptor | −1.54 | – | – | 2.51 | |

| Cell cycle | CCND2 | Cyclin D2 | – | – | 2.38 | 5.42 |

| CCNE1 | Cyclin E1 | – | – | 2.05 | 4.76 | |

| PMP22 | Peripheral myelin protein 22 | – | – | 2.03 | 3.51 | |

| S100A4 | S100 calcium binding protein A4 | – | – | 2.05 | 2.34 | |

| S100A2 | S100 calcium binding protein A2 | – | −1.53 | – | 2.55 | |

| PTTG1 | Pituitary tumor-transforming protein 1 | 2.51 | ||||

| Cell growth/proliferation | TIMP2 | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 | – | – | 2.31 | 7.96 |

| CYR61 | Cysteine-rich, angiogenic inducer, 61 | – | – | 2.48 | 2.89 | |

| EGR1 | Early growth response 1 | 2.37 | – | 2.65 | 1.84 | |

| FGF1 | Fibroblast growth factor 1, acidic | – | 2.13 | 2.25 | 2.77 | |

| VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor A | – | – | 2.46 | – | |

| VEGFC | Vascular endothelial growth factor C | – | – | 2.07 | 22.23 | |

| CSRP2 | Cysteine and glycine-rich protein 2 | – | – | 1.72 | 11.25 | |

| SERPINE2 | Serpin peptidase Inhibitor, clade E member 2 | – | – | – | 2.86 | |

| CD320 | CD320 molecule | – | – | – | 2.85 | |

| Cell structure | COL1A2 | Collagen, type I, alpha 2 | – | −2.57 | – | −2.22 |

| FGD4 | FYVE, RhoGEF and PH domain containing 4 | – | – | −1.51 | −3.13 | |

| PALLD | Palladin, cytoskeletal associated protein | – | – | – | 3.64 | |

| MAP1B | Microtubule-associated protein 1B | – | – | – | 3.23 | |

| TUBB | Tubulin, beta | – | – | – | 2.90 | |

| Cell adhesion | SELP | Selectin P | – | – | 2.29 | 7.23 |

| VCAM1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 | – | – | 2.18 | – | |

| THBS | Thrombospondin 1 | – | −1.67 | 2.05 | 1.52 | |

| THBS2 | Thrombospondin 2 | – | −1.63 | 2.13 | 1.62 | |

| LGALS1 | Lectin, galactoside-binding, soluble, 1 | – | – | 1.71 | 11.61 | |

| TPBG | Trophoblast glycoprotein | – | – | 1.58 | 3.60 | |

| CLDN16 | Claudin 16 | – | – | – | −2.70 | |

| PARVB | Parvin, beta | – | – | – | 2.71 | |

| LAMA3 | Laminin, alpha 3 | – | – | – | −2.61 | |

| Stress response | USP2 | Ubiquitin specific peptidase 2 | – | – | – | −3.92 |

| SERPINH1 | Serpin peptidase Inhibitor, clade H member 1 | – | – | 1.51 | 3.03 | |

| Apoptosis | DRAM | DNA-damage regulated autophagy modulator 1 | – | – | −1.62 | −3.20 |

| CYCS | Cytochrome c, somatic | – | – | – | 2.90 | |

| TIMP4 | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 4 | – | – | −1.65 | −3.28 | |

| Immune response | IFI30 | Interferon-gamma-inducible protein 30 | – | – | 1.66 | 24.16 |

| IL8 | Interleukin-8 | – | – | 3.75 | – | |

| CXCL5 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 | – | – | 3.63 | – | |

| CXCL1 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 | – | – | 2.52 | – | |

| CCL26 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 26 | – | – | 2.11 | 1.63 | |

| CXCR4 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 | – | – | – | −2.71 | |

| SERPINE1 | plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 | – | −1.53 | 3.19 | – | |

| PLAU | Plasminogen activator, urokinase | – | 1.90 | 2.64 | 1.88 | |

| PLAT | plasminogen activator, tissue | – | – | 1.54 | 8.77 | |

| C3 | Complement component 3 | – | – | 2.54 | 2.60 | |

| CFB | Complement factor B | – | – | 2.78 | 2.50 | |

| C1QBP | Complement component 1, q subcomponent binding protein | – | – | – | 2.56 | |

| CD200 | CD200 molecule | – | – | – | 6.51 | |

| TAP1 | Transporter 1, ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B | 3.49 | ||||

| Unknown function | TM4SF18 | Transmembrane 4 L six family member 1 | – | – | – | 3.28 |

| SYNGR2 | Synaptogyrin 2 | – | – | 1.61 | 5.93 | |

| DBNDD2 | Dysbindin (dystrobrevin binding protein 1) domain containing 2 | – | – | 1.79 | 3.26 | |

| FIBIN | Fin bud initiation factor homolog | – | – | 1.61 | −3.09 | |

| GLIPR2 | GLI pathogenesis-related 2 | – | – | 2.06 | 3.00 | |

| B9D1 | B9 protein domain 1 | 1.55 | 2.75 | |||

| GPM6B | Glycoprotein M6B | – | – | – | −3.17 | |

| PALD | KIAA1274 | – | – | – | −2.89 | |

| HIGD1D | HIG hypoxia inducible domain family, member 1D | – | – | – | 2.62 | |

| SELM | Selenoprotein M | – | – | – | 2.85 | |

Only genes with ≥ 2-fold (4 h, 4 and 8 d) and ≥ 2.5-fold (14 d) changes in at least one tested time point versus non-infected controls are considered.

The proportion of molecules commonly regulated in the course of infection was generally low early after infection but increased later on. FOS was the only gene transcript significantly up-regulated ≥ 1.5-fold at all four time points. Considering the last three time points, an overlapping gene subset of 17 molecules was influenced by E. bovis infection on days 4, 8 and 14 p.i. Comparing data generated on days 4 vs. 8 and 4 vs. 14 p.i., 7 additional molecules overlapped each. Additionally, 94 molecules overlapped when comparing regulated gene transcripts on days 8 vs. 14 p.i., with 63% of the molecules modulated at day 8 p.i. being equally influenced 6 days later. Within this set of common molecules, in 82%, the transcription was even enhanced 14 days p.i.

3.3. Functional analyses of gene sets regulated by E. bovis

3.3.1. Predicted functional effects

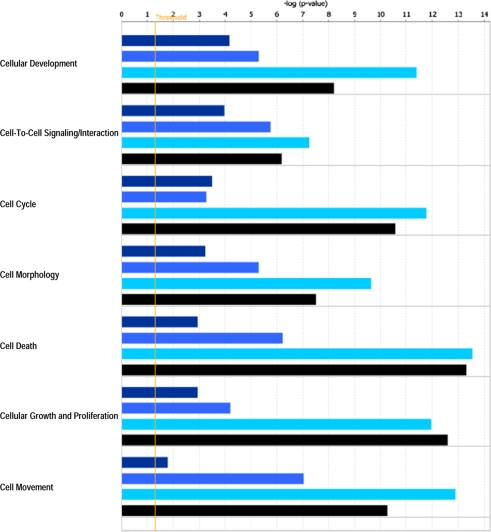

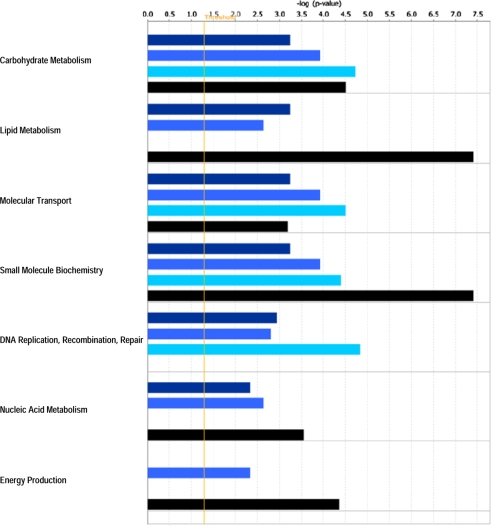

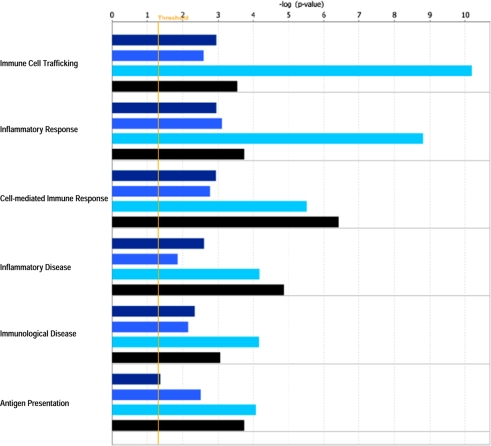

IPA revealed various host cell biofunctions to be significantly regulated by E. bovis infection, the majority of which dealt with general cell-related functions (Fig. 2), metabolism/biosynthesis (Fig. 3) and immune response (Fig. 4). In general, an increasing probability of involvement was associated with ongoing infection. It is noteworthy that regulation of the cell cycle was clearly enhanced in the late phase of infection on 8 and 14 days p.i. Genes associated with metabolism/biosynthesis-related functions included many involved in carbohydrate metabolism, molecular transport and small molecule biochemistry (Fig. 3). In addition, late E. bovis infection (14 days p.i.) significantly regulated molecules involved in lipid metabolism, nucleic acid metabolism and energy production. E. bovis infection also altered the host cell immune response. Whilst major reactions related to immune cell trafficking and inflammatory response were restricted to 8 days p.i., molecules involved in cell-mediated immune response and antigen presentation were significantly affected 4–14 days p.i. (Fig. 4). A more precise overview detailing the number of genes involved in host cell functions and respective p-values as well as identified molecules involved in different functions is given in the Supplementary Tables I and II, respectively, available on line only.

Figure 2.

Biofunctions related to general cell characteristics significantly affected in endothelial host cells by E. bovis infection. A Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate a p-value (bars) determining the probability that the association between the genes in the different datasets (4 h p.i. = dark blue bars, 4 days p.i. = medium blue bars, 8 days p.i. = bright blue bars, 14 days p.i. = black bars) and the respective biofunctions can be explained by random chance. The threshold (yellow line) refers to the cut off for p ≤ 0.05. (A color figure is available at www.vetres.org.)

Figure 3.

Metabolism-related biofunctions significantly regulated in endothelial host cells by E. bovis infection. A Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate a p-value (bars) determining the probability that the association between the genes in the different datasets (4 h p.i. = dark blue bars, 4 days p.i. = medium blue bars, 8 days p.i. = bright blue bars, 14 days p.i. = black bars) and the respective biofunctions can be explained by random chance. The threshold (yellow line) refers to the cut off for p ≤ 0.05. (A color figure is available at www.vetres.org.)

Figure 4.

Biofunctions related to immune responses significantly affected in endothelial host cells by E. bovis infection. A Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate a p-value (bars) determining the probability that the association between the genes in the different datasets (4 h p.i. = dark blue bars, 4 days p.i. = medium blue bars, 8 days p.i. = bright blue bars, 14 days p.i. = black bars) and the respective biofunctions can be explained by random chance. The threshold (yellow line) refers to the cut off for p ≤ 0.05. (A color figure is available at www.vetres.org.)

3.3.2. Predicted signaling pathways

The most significantly affected pathway was the aryl hydrocarbon receptor signalling pathway, which was significantly over-represented in E. bovis-infected cells at 4 h, 8 and 14 days p.i. (Tab. II). It is noteworthy that two signalling pathways referring to cell cycle regulation (G1/S checkpoint regulation, G2/M checkpoint DNA damage regulation, 8 and 14 days p.i.) and stress response (NRF2-mediated oxidative stress response, 14 days p.i.) were exclusively over-represented by regulated genes in the late phase of E. bovis infection.

Table II.

Canonical pathways significantly over-represented by E. bovis-regulated genes in infected bovine endothelial host cells (p ≤ 0.05).

| Canonical Pathwaya | p.i. | Molecules |

|---|---|---|

| Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Signaling | 4 h | FOS, CYP1A1 |

| 8 d | NR2F1, MYC, FOS, CCNE1, CCND2, TGFB2 | |

| 14 d | GSTM1, MGST1, CCNE2, GSTP1, IL6, MYC, NR2F1, FOS, CCNE1, JUN, CCND3, CCND2, SP1, CDKN1A, ALDH1A2, TGFB2, HSP90AA1, ALDH18A1, HSPB1, GSTK1 |

|

| HMGB1 Signaling | 4 d | FOS, SERPINE1 |

| 8 d | IL8, FOS, VCAM1, ICAM1, SERPINE1, PLAT | |

| 14 d | KAT2B, FOS, JUN, MAPK14, SP1, CDC42, RBBP7, MRAS, IFNGR2, PIK3R2, PLAT |

|

| HGF Signaling | 14 d | MAP3K11, CDC42, PLCG1, IL6, FOS, JUN, GAB1, CDKN1A, MRAS, PRKCH, MAP3K8, PIK3R2, ELK3, MAP3K3 |

| IGF-1 Signaling | 4 d | FOS, IGFBP5, NEDD4 |

| 14 d | FOS, YWHAG, JUN, NOV, YWHAH, MRAS, RPS6KB2, IGFBP5, PRKCH, PIK3R2, CYR61, GRB10 |

|

| ERK5 Signaling | 4 h | FOS |

| 14 d | MYC, FOS, YWHAG, YWHAH, GAB1, MRAS, RPS6KB2, MAP3K8, MEF2C, RPS6KA5, MAP3K3 |

|

| NRF2-mediated Oxidative Stress Response | 14 d | AKR7A2, GSTM1, GSTP1, USP14, MGST1, DNAJC3, DNAJA1, FOS, MAPK14, SOD2, JUN, SCARB1, STIP1, MRAS, UBE2K, DNAJC1, PRKCH, PIK3R2, DNAJB6, GSTK1 |

| Protein Ubiquitination Pathway | 14 d | PSMB9, UCHL3, USP14, PSMB5, PSMD7, PSMC4, USP54, THOP1, UBE2S, HSPA5, USP2, PSMB6, TAP1, PSMD8, UBE2F, UCHL1, HSPA8, USP53, PSMB2, HSP90AA1, PSMD14, USP40, UBE2E1 |

| Acute Phase Response | 8 d | SOCS1, FOS, SOD2, C1S, NOLC1, CFB, SERPINE1 |

| Leukocyte Extravasation Signaling | 8 d | TIMP4, VCAM1, ICAM1, EZR, TIMP2 |

| 14 d | TIMP3, CDC42, CXCR4, MMP16, PLCG1, RAPGEF3, WIPF1, TIMP4, MAPK14, CDH5, CLDN1, EZR, CYBA, CLDN16, CD44, MMP11, PRKCH, PIK3R2, VCL, TIMP2 |

|

| IL-8 Signaling | 8 d | IL8, VCAM1, ICAM1, CCND2, CXCL1, VEGFC |

| Coagulation System | 4 d | PLAUR, PLAU, SERPINE1 |

| 8 d | PLAUR, PLAU, SERPINE1, PLAT | |

| Cell Cycle: G1/S Checkpoint Regulation | 8 d | MYC, CCNE1, CCND2, TGFB2 |

| 14 d | MYC, CCNE2, CCNE1, CCND3, HDAC3, CCND2, CDKN1A, TGFB2 |

|

| Cell Cycle: G2/M DNA Damage Regulation | 8 d | TOP2A, CCNB2, BRCA1 |

| 14 d | KAT2B, GADD45A, PTPMT1, CDKN1A, TOP2A, CCNB2 |

As generated by Ingenuity Pathway Analyses program.

3.3.3. Predicted gene networks

IPA constructed 1, 3, 9 and 25 inter-connected gene networks that were significantly altered as a result of E. bovis infection 4 h, 4, 8 and 14 days after infection, respectively.

The most significant network over-represented by E. bovis-regulated genes at 4 days p.i. concerned cardiovascular system development/function, organ morphology and organismal functions (Supplementary Fig. 1, available online at www.vetres.org) focussing on the transcription regulators FOS and ANKRD1.

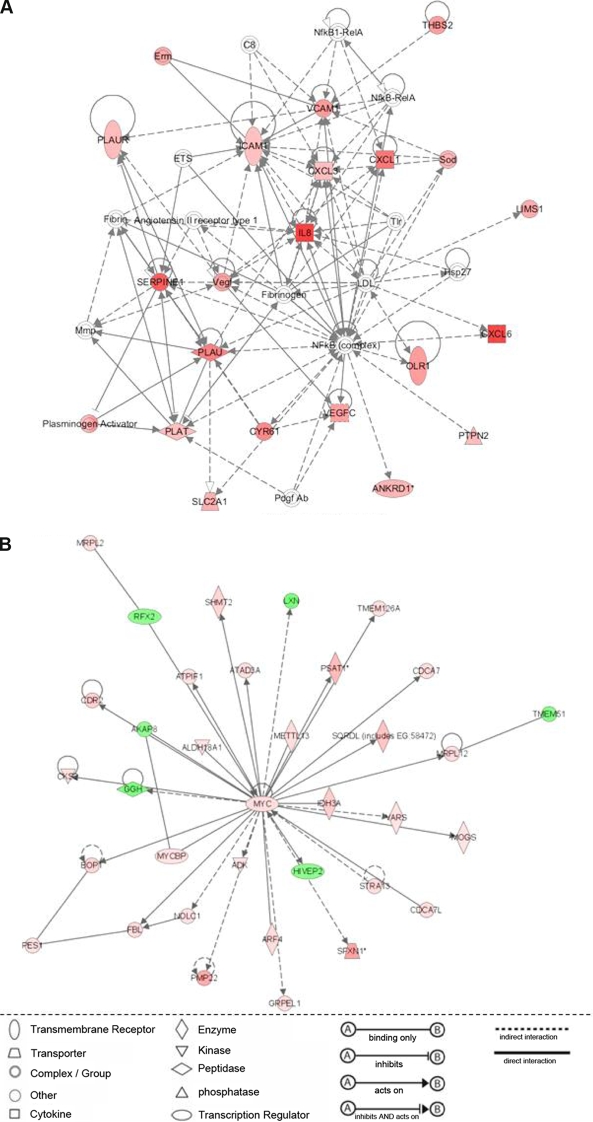

The most significant network at 8 days p.i. referred to cellular movement, immune cell trafficking and host cell inflammatory response (Fig. 5A). Out of 35 network-forming molecules, 18 were modulated by E. bovis infection and all were up-regulated. Up-regulation especially concerned chemokines (IL-8, CXCL1, CXCL3, CXCL6) and adhesion molecules (VCAM1, ICAM1), but also focussed on the regulation of coagulation (PLAU, PLAUR, PLAT, SERPINE1).

Figure 5.

Molecular networks over-represented by E. bovis-regulated host cell molecules 8 (A) and 14 (B) days after in vitro infection. A list of significantly (p ≤ 0.05) regulated molecules in E. bovis-infected endothelial host cells 4, 8 and 14 days after infection was individually subjected to Ingenuity Pathway Analyses which generated highly significant networks displaying up-regulated molecules in red and down-regulated ones in green. (A) Network on molecules involved in cellular movement, immune cell trafficking and inflammatory response (8 days p.i.). (B) Network on molecules involved in cellular assembly and organisation, gene expression and infection mechanism (14 days p.i.). (A color figure is available at www.vetres.org.)

The most significant network at 14 days p.i. concerned cellular organisation, gene expression and infection mechanisms (Fig. 5B). All network-forming genes were modulated by E. bovis infection resulting in a MYC-centered gene network with the majority of genes being up-regulated.

Another network significantly influenced by E. bovis infection referred to the regulation of cell cycle, cellular development, cellular growth and proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 2, available online at www.vetres.org). In this network a high number of transcription regulators (SOX18, KLF4, KLF5, ID3, MEF2C, PHB) were affected.

4. DISCUSSION

In this investigation we performed a transcriptional profiling of E. bovis-infected host endothelial cells to obtain global insights into parasite-triggered host cell modulation. Considering the total number of regulated genes and the overlapping gene sets, it appears that in vitro development of meronts I can be divided into an early phase (4 h, 4 days p.i.) with poor regulatory processes on the transcriptional level and a more transcriptionally active late phase (8, 14 days p.i.) beginning with the onset of parasite proliferation.

The in vitro culture used in this investigation corresponded well with the host cell type, the duration of meront I development and the resulting size of these stages to those reported in vivo [13]. The reduction of infection rates with progression of infection may result from the consistent observation that not all sporozoites having successfully invaded host cells undergo further development in vitro which agrees with ex vivo histological studies on E. bovis-infected ileum mucosa3 and those reported for other Eimeria spp. infections [25]. Furthermore, as reported for other apicomplexan-infected host cells [29], some vital early meronts reproducibly disintegrate from the cell layer and are lost during the following cell feeding procedure. Taken together, these facts indicate that the in vitro system used in this investigation relates to the situation in vivo.

To assure that the regulation of gene transcription was parasite-induced and to exclude effects based on cell aging processes we performed non-infected control samples for every time point and every BUVEC isolate. Direct comparisons of infected BUVEC isolates with the respective non-infected cells revealed significant parasite-driven effects. Given that with progression of infection the number of regulated genes increases – although less infected cells carrying respective stages were detected – demonstrates stage-specific, parasite-triggered modulation. The fact that identical molecules regulated 8 and 14 days p.i. are mostly found to be increased in their gene transcription at the later time point strengthens enhanced parasite-driven host cell regulation towards the end of merogony I.

The observed changes in host cell nucleus morphology coincided with increasing numbers of regulated genes during the late phase of E. bovis infection. Enhanced transition of hetero- to euchromatin is indicative of a transcriptionally active cell and was exclusively observed from 8 days p.i. onwards. The finding that most regulated gene transcripts were detected 8 and 14 days p.i. supports this hypothesis. Among these transcripts, some key regulators of gene transcription (FOS, MYC, STAT1) and various other transcription factors (ANKRD1, ANKRD52, BHLHB2, GTF2E2, GTF2H3, EZH2, KLF4, KLF5) were up-regulated. Especially the MYC-centred gene network generated at 14 days p.i., which indicates high transcriptional activity of E. bovis-infected host cells.

An intriguing morphological observation was the consistent arrest of the nuclear “fried-egg”-morphology after this status had appeared. In non-infected cells this morphology indicates the interphase of a cell which changes again as soon as the cell displays mitotic activity [1]. In E. bovis-infected endothelial cells, the morphology remained stable irrespective of ongoing development or host cell type, an observation that has also been made for a macromeront-forming Eimeria species of the goat, Eimeria ninakohlyakimovae 4. Overall, this phenomenon may indicate a parasite-induced arrest in cell cycle from 8 days onwards. Accordingly, the predicted influence of E. bovis-regulated genes on the cell cycle was of a higher significance at days 8 and 14 p.i. than at earlier time points. This was also reflected in the signalling pathways on G1/S checkpoint regulation and G2/M checkpoint DNA damage regulation which were over-represented in E. bovis-infected host cells. However, when considering total parasite-triggered modulation of the cell cycle regulatory machinery, both cell cycle progress and arrest seem to have been affected. Up-regulation of different cyclins (CCNB2, CCND2, CCNE1, CCNE2) and related molecules (CDK2AP1, GADD45A), as well as down-regulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1C, favour cell cycle progress [22–24, 28]. In contrast, down-regulation of CCND3 and up-regulation of inhibitory molecules (CDKN1A, BRCA1) argues for a cell cycle arrest [11, 20, 24, 33, 34].

Once the parasite starts to grow and divide within the cell, it must acquire nutrients through or from the host cell. In contrast to T. gondii, which exhibits well-documented auxotrophies for purines [17], hypoxanthine, xanthine and other molecules [26], no data are available for the nutritional requirements of E. bovis or other eimerian species. Although different metabolic categories, such as carbohydrate, lipid and nucleic acid metabolism, were significantly modulated by E. bovis infection at almost all time points investigated, overall, most metabolism/biosysnthesis-related molecules were influenced at 14 days p.i. (i.e. when parasite proliferation was fully active). Genes up-regulated in infected host cells were then involved in pathways of carbohydrate biosynthesis and metabolism such as amino sugar, fructose/mannose, galactose, nucleotide sugar and pyrovate metabolism as well as in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and the pentose phosphate pathway, indicating that transcriptional alteration of the basic host cell metabolism is pivotal for intracellular growth of meronts I.

T. gondii has to scavenge host cholesterol since it cannot synthesize sterols de novo via the mevalonate pathway [7, 27]. Interestingly, 16 molecules involved in cholesterol biosynthesis and metabolism were significantly up-regulated in E. bovis-infected host cells 14 days p.i., which may indicate comparable nutritional needs in both parasites. Most notable was the up-regulation of squalene epoxidase (SQLE), which is reported to be one of the rate-limiting enzymes in the mevalonate pathway and which was also induced in porcine and human T. gondii-infected host cells [6, 21].

At 14 days p.i., molecules contributing to the metabolism of malic acid (MDH1, MDH2, ME1) were also up-regulated in infected cells, indicating an increased need for energy production towards the end of merogony I.

E. bovis meront I development within the endothelial cell generally leads to enormous alteration of host cell characteristics concerning cell size and subcellular organisation. Hermosilla et al. [16] reported an increasing influence on actin- and tubulin-related reorganisation of the host cell cytoskeleton with ongoing infection. We now found enhanced gene transcription of several tubulins (TUBB, TUBB4, TUBB6) and of molecules involved in microtubule binding or cytoskeleton organisation (TPPP, DOCK7, CKAP4, DCT3) in the late phase of infection. Also vinculin and ezrin, molecules involved in actin cytoskeleton signalling, and other actin-related genes (CAPG, CNN2, TAGLN, PALLD) were up-regulated at the meront I stage and may contribute to the cytoskeleton re-structuring process induced by the formation of this parasitic stage.

The vast reorganisation and enlargement of E. bovis infected host cells in the late phase of meront I formation causes considerable cell stress, which is reflected in up-regulation of several heat shock proteins (HSP90AA1, HSP90B1, HSP70, HSP70-3, HSP70-5, HSP27, HSPB6) and other stress-related molecules, such as SERP1 and STIP1 at day 14 p.i. The latter coordinates the functions of HSP70 and HSP90. HSP are also closely linked to host cell apoptosis, since certain members exhibit anti-apoptotic effects via both the receptor-mediated pathway and the inner, mitochondrial pathway [3, 4]. It is well known that intracellular stages of other apicomplexan parasites modulate host cell apoptosis to guarantee successful intracellular development (for review see [12]). Lang et al. [18] have recently shown that E. bovis-infected cells are defended from apoptosis by enhanced expression of the anti-apoptotic molecules c-FLIP and c-IAP1. The current data confirm up-regulation of c-IAP at 8 days p.i. and provide new candidates repressing apoptosis, either by their up-regulation (DDIT4, BCL2A1) or by decreased abundance (BOK). However, the modulated abundance of several other molecules rather argues for enhanced host cell apoptosis (BAG5, BAK1, BCL2L14, CYCS, COX5A, DAP3).

Previous work has shown that interactions of E. bovis and endothelial cells result in inflammatory processes associated with the adhesion of PMN [15] and PBMC [31] to infected cell layers and enhanced transcription of genes encoding for immune-modulatory molecules [30]. The enhanced host cell immune responses described here support these reports, most notably on day 8 p.i. when a respective gene network was generated involving various up-regulated chemokines, adhesion molecules and factors of coagulation. Interestingly, all up-regulated chemokines belonged to the CXC-family (CXCL1, CXCL3, CXCL6, CXCL8), molecules predominantly acting on PMN and/or lymphocytes [19, 35], both of which are stimulated in E. bovis infections [5, 32]. Up-regulation of the adhesion molecules VCAM1, ICAM1 and SELP may directly contribute to the above mentioned adhesion of leukocytes to infected cell layers [15, 31].

The precise role of molecules involved in coagulation (i.e. PLAU, PLAUR, PLAT, SERPINE1), in E. bovis infection is not known. Given that pro-inflammatory reactions at the endothelial site are generally accompanied by enhanced permeability of cell layers, activation of the coagulation system may represent an additional sign of parasite-triggered endothelial cell activation. The induction of CFB, CFH, C1S and C3, molecules involved in the complement cascade, may also be seen in this sense. Overall, the inflammatory response at 8 days p.i. was also reflected in regulated canonical pathways in E. bovis-infected host cells. Involvement in IL-8 signalling, leukocyte extravasation signalling and in the coagulation system has already been mentioned above. Moreover, E. bovis infection induced HMBG1 signalling on days 4, 8 and 14 p.i., a pathway leading to the release of pro-inflammatory molecules.

In conclusion, the current investigation has identified numerous gene transcripts regulated by E. bovis during in vitro infection for the first time. The induction of cholesterol- and carbohydrate-related pathways shed light on Eimeria-associated nutritional needs for intracellular growth. Various indications from transcripts associated with host cell apoptosis, immune response and cell cycle regulation provide useful tools for more detailed, prospective studies on Eimeria-host cell interactions.

ONLINE MATERIAL

Supplementary Figure 1.

Supplementary Figure 2.

Acknowledgments

We greatly acknowledge B. Hofmann and B. Reinhardt for their excellent technical assistance in cell culture and A. Jugert for the technical support in microarray analyses. Furthermore, we thank the Bioinformatic Platform of Andalucia, Spain, for the access to Ingenuity Pathway Analyses. This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (project TA 291/1-2).

Footnotes

Affimetrix GeneChip Expression Analysis, Technical Manual, 2001.

Affimetrix, Technical Note. Guide to probe logarithmic intensity error (Plier) estimation, 2005.

Hermosilla C., unpublished observation.

Ruiz A., personal observation.

References

- 1.Alberts B., Johnson A., Lewis J., Raff M., Roberts K., Walter P., Molecular biology of the cell, 2008, 5th edition, pp. 363 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alcala-Canto Y., Ibarra-Velarde F., Cytokine gene expression and NF-kappaB activation following infection of intestinal epithelial cells with Eimeria bovis or Eimeria alabamensis in vitro, Parasite Immunol. (2008) 30:175–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beere H.M., Wolf B.B., Cain K., Mosser D.D., Mahboubi A., Kuwana T., et al., Heat-shock protein 70 inhibits apoptosis by preventing recruitment of procaspase-9 to the Apaf-1 apoptosome, Nat. Cell Biol. (2000) 2:469–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beere H.M., Death versus survival: functional interaction between the apoptotic and stress-inducible heat shock protein pathways, J. Clin. Invest. (2005) 115:2633–2639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behrendt J.H., Hermosilla C., Hardt M., Failing K., Zahner H., Taubert A., PMN-mediated immune reactions against Eimeria bovis , Vet. Parasitol. (2008) 151:97–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blader I.J., Manger I.D., Boothroyd J.C., Microarray analysis reveals previously unknown changes in Toxoplasma gondii-infected human cells, J. Biol. Chem. (2001) 276:24223–24231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coppens I., Sinai A.P., Joiner K.A., Toxoplasma gondii exploits host low-density lipoprotein receptor-mediated endocytosis for cholesterol acquisition, J. Cell Biol. (2000) 149:167–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daugschies A., Bürger H.J., Akimaru M., Apparent digestibility of nutrients and nitrogen balance during experimental infection of calves with Eimeria bovis, Vet. Parasitol. (1998) 77:93–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Cacho E., Gallego M., Lopez-Bernad F., Quilez J., Sanchez-Acedo C., Expression of anti-apoptotic factors in cells parasitized by second-generation schizonts of Eimeria tenella and Eimeria necatrix, Vet. Parasitol. (2004) 125:287–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzgerald P.R., The economic impact of coccidiosis in domestic animals, Adv. Vet. Sci. Comp. Med (1980) 24:121–143 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galbiati F., Volonte D., Liu J., Capozza F., Frank P.G., Zhu L., et al., Caveolin-1 expression negatively regulates cell cycle progression by inducing G(0)/G(1) arrest via a p53/p21(WAF1/Cip1)-dependent mechanism, Mol. Biol. Cell (2001) 12:2229–2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graumann K., Hippe D., Gross U., Luder C.G., Mammalian apoptotic signalling pathways: multiple targets of protozoan parasites to activate or deactivate host cell death, Microbes Infect. (2009) 11:1079–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammond D.M., Davis C.R., Bowmann L., Experimental infections with Eimeria bovis in calves, Am. J. Vet. Res. (1964) 5:303–311 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hermosilla C., Barbisch B., Heise A., Kowalik S., Zahner H., Development of Eimeria bovis in vitro: suitability of several bovine, human and porcine endothelial cell lines, bovine fetal gastrointestinal, Madin-Darby bovine kidney (MDBK) and African green monkey kidney (VERO) cells, Parasitol. Res. (2002) 88:301–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hermosilla C., Zahner H., Taubert A., Eimeria bovis modulates adhesion molecule gene transcription in and PMN adhesion to infected bovine endothelial cells, Int. J. Parasitol. (2006) 36:423–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hermosilla C., Schröpfer E., Stowasser M., Eckstein-Ludwig U., Behrendt J.H., Zahner H., Cytoskeletal changes in Eimeria bovis-infected host endothelial cells during first merogony, Vet. Res. Commun. (2008) 32:521–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krug E.C., Marr J.J., Berens R.L., Purine metabolism in Toxoplasma gondii, J. Biol. Chem. (1989) 264:10601–10607 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang M., Kann M., Zahner H., Taubert A., Hermosilla C., Inhibition of host cell apoptosis by Eimeria bovis sporozoites, Vet. Parasitol. (2009) 160:25–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Locati M., Otero K., Schioppa T., Signorelli P., Perrier P., Baviera S., Sozzani S., Mantovani A., The chemokine system: tuning and shaping by regulation of receptor expression and coupling in polarized responses, Allergy (2002) 57:972–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacLachlan T.K., Takimoto R., el-Deiry W.S., BRCA1 directs a selective p53-dependent transcriptional response towards growth arrest and DNA repair targets, Mol. Cell. Biol. (2002) 22:4280–4292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okomo-Adhiambo M., Beattie C., Rink A., cDNA microarray analysis of host-pathogen interactions in a porcine in vitro model for Toxoplasma gondii infection, Infect. Immun. (2006) 74:4254–4265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quelle D.E., Ashmun R.A., Shurtleff S.A., Kato J.Y., Bar-Sagi D., Roussel M.F., Sherr C.J., Overexpression of mouse D-type cyclins accelerates G1 phase in rodent fibroblasts, Genes Dev. (1993) 7:1559–1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherr C.J., Mammalian G1 cyclins, Cell (1993) 73:1059–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherr C.J., Roberts J.M., CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression, Genes Dev. (1999) 13:1501–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi M., Huther S., Burkhardt E., Zahner H., Lymphocyte subpopulations in the caecum mucosa of rats after infections with Eimeria separata: early responses in naive and immune animals to primary and challenge infections, Int. J. Parasitol. (2001) 31:49–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sibley L.D., No more free lunch, Nature (2002) 415:843–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinai A.P., Joiner K.A., Safe haven: the cell biology of nonfusogenic pathogen vacuoles, Annu. Rev. Microbiol. (1997) 51:415–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stillman B., Cell cycle control of DNA replication, Science (1996) 274:1659–1664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sturm A., Amino R., van de S.C., Regen T., Retzlaff S., Rennenberg A., et al., Manipulation of host hepatocytes by the malaria parasite for delivery into liver sinusoids, Science (2006) 313:1287–1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taubert A., Zahner H., Hermosilla C., Dynamics of transcription of immunomodulatory genes in endothelial cells infected with different coccidian parasites, Vet. Parasitol. (2006) 142:214–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taubert A., Zahner H., Hermosilla C., Eimeria bovis infection enhances adhesion of peripheral blood mononuclear cells to and their transmigration through an infected bovine endothelial cell monolayer in vitro, Parasitol. Res. (2007) 101:591–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taubert A., Hermosilla C., Sühwold A., Zahner H., Antigen-induced cytokine production in lymphocytes of Eimeria bovis primary and challenge infected calves, Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. (2008) 126:309–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Oirschot B.A., Stahl M., Lens S.M., Medema R.H., Protein kinase A regulates expression of p27(kip1) and cyclin D3 to suppress proliferation of leukemic T cell lines, J. Biol. Chem. (2001) 276:33854–33860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan Y., Spieker R.S., Kim M., Stoeger S.M., Cowan K.H., BRCA1-mediated G2/M cell cycle arrest requires ERK1/2 kinase activation, Oncogene (2005) 24:3285–3296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zlotnik A., Yoshie O., Nomiyama H., The chemokine and chemokine receptor superfamilies and their molecular evolution, Genome Biol. (2006) 7:243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1.

Supplementary Figure 2.