Abstract

Charged with the task of providing a molecular link between adjacent cells, the cadherin superfamily consists of over 100 members and populates the genomes of organisms ranging from vertebrates to cniderians. This breadth hints at what decades of research has confirmed: that cadherin-based adhesion and signaling events regulate diverse cellular processes including cell-sorting, differentiation, cell survival, proliferation, cell polarity, and cytoskeletal organization.

Introduction and context

Cadherin structure and dimerization

The term cadherin stems from the functional definition of this family as calcium-dependent adhesion molecules. Classical type-I cadherins such as E-cadherin and N-cadherin are single-pass transmembrane proteins consisting of highly conserved extracellular and intracellular domains. Extracellular cadherin domains, which structurally rely on intercalated calcium and contain a conserved His-Ala-Val (HAV) motif [1,2], extend from the cell surface and bind to cadherins present on adjacent cells. Apposing cadherins exchange N-terminal beta-strands in a process that involves the insertion of a tryptophan into a hydrophobic pocket present on the partner cadherin [3]. Conserved intracellular domains bind to catenins (cytoplasmic proteins belonging to the ‘armadillo’ family) [2].

Type-II cadherins, such as cadherin-11, also bind catenins and utilize strand swapping to form trans-dimers, but lack a HAV motif, require two N-terminal tryptophans, and in turn, a larger hydrophobic acceptor pocket for dimerization [2,4].

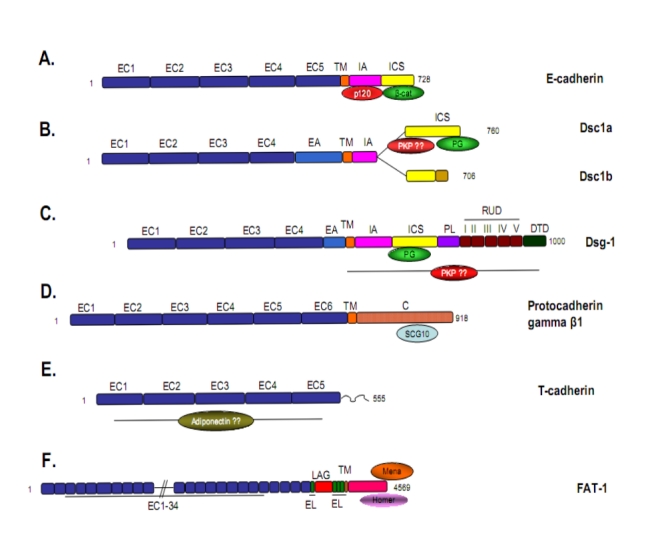

Non-classical cadherin subfamilies include desmosomal cadherins, seven-pass transmembrane cadherins, large cadherins of the fat and dachsous groups and protocadherins. They share varying levels of homology with classic cadherins but are not as well understood with respect to adhesive mechanisms [5] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Examples from the cadherin superfamily.

(A) The classic type I cadherin, E-cadherin, populates adherens junctions in numerous epithelial tissues, forms adhesive dimers and connects to actin and signaling pathways via beta-catenin and p120. Type II cadherins like VE-cadherin are similar but lack a HAV domain. (B) Desmocollin 1 (Dsc1) and (C) Desmoglein-1 (Dsg1) are desmosomal cadherins which resemble classic cadherins with respect to the ectodomain and the catenin binding region, however, they bind plakoglobin (Pg) and plakophilins (PKP) rather than beta-catenin and p120 and connect to intermediate filaments. Dsg1 has several unique, uncharacterized domains which extend beyond classic cadherins. Desmocollin ‘b’ differs from ‘a’ in that it has a short unique sequence at its C-terminal end and cannot bind Pg. (D) Protocadherins are heavily expressed in neural tissue and contain conserved ectodomains, but do not bind catenins. The cytoplasmic tail of gamma β-1 associates with the microtubule binding protein SCG10 and, in turn, modulates cytoskeletal dynamics [42]. (E) An atypical cadherin, T-cadherin is the only family member that lacks a transmembrane domain. Instead it associates with the plasma membrane through a GPI-anchor. An association between T-cadherin and adiponectin may contribute to carcinogenesis [43,44]. (F) Fat-1 typifies the large cadherins; although it [jam1]contains 34 ectodomains with homology to classic cadherins, it does not have a clear adhesive function but appears to modulate intracellular signaling events, particularly cytoskeletal re-organization through binding partners like Mena and Homer [45]. For a more extensive review of cadherin family members see Nollet et al. [5]. C, cytoplasmic domain; DTD, desmoglein terminal domain; EA, extracellular anchor domain; EC, extracellular cadherin domain; EL, EGF-like repeat; ICS, intracellular cadherin sequence; LAG, Laminin A G-repeat; PL, proline rich linker; RUD, repeating unit domain; TM, transmembrane.

Major recent advances

Regulation of cell sorting

Early experiments by Nose et al. [6] demonstrated that mixed cultures established from non-adherent L-cells ectopically expressing either E-cadherin or P-cadherin, sorted into clusters of cells expressing the same type of cadherin molecule. These data implied not only that binding between cadherins was homophilic but also that differential cadherin expression could regulate the separation of cells into distinct populations and eventually distinct tissues during development. More recent data, however, challenges the notion that homophilic cadherin dimerization alone dictates cell sorting. CHO cells transfected with various cadherins also display cell-sorting behavior, but when plated on substrates coated with human E-cadherin or Xenopus C-cadherin, cells adhered to both substrates with equivalent affinity [7]. In accord, Shi et al. [8] and Prakasham et al. [9] demonstrated that chicken N-CAD, canine E-CAD, and Xenopus C-CAD all cross-react, forming heterophilic bonds that do not differ mechanically or kinetically from homophilic bonds. Similar heterophilic interactions have been described amongst desmosomal cadherins as well [10,11]. Furthermore, evidence suggests that cells expressing different cadherins may segregate based disparities in surface tension energy arising from differences in cadherin expression levels, rather than on homotypic cadherin dimerization alone. Malcolm Steinberg introduced this theory, termed the differential adhesion hypothesis in the 1970s, and provided further evidence with Foty in 2005 [12]; demonstrating that two clones of L-cells expressing the same cadherin at different levels segregate such that low-expression clones envelop high-expression cells. While animal models confirm the importance of cadherins in tissue development [13-16], the molecular mechanism by which cadherins mediate cell sorting and the extent to which their adhesive properties dictate this event remains an active area of investigation.

Regulation of adhesive structures

Sites of cadherin-based adhesion are often organized in distinct cellular structures comprised of unique protein scaffolds connected, directly or indirectly, to the cytoskeleton. Whereas the extracellular domains of classic cadherins participate in adhesion, the cytoplasmic domains associate with proteins that participate in actin anchorage and/or cortical actin remodeling at the adherens junction, including the armadillo proteins p120-catenin and β-catenin, the latter of which interacts with α-catenin. Desmosomal cadherins, divided into desmogleins and desmocollins, interact with a different set of armadillo proteins including plakoglobin and the plakophilins, which in turn link to intermediate filaments through a cytolinker called desmoplakin, forming adhesive structures known as desmosomes. The intracellular armadillo proteins may also serve regulatory roles in signal transduction pathways as evidenced by the vast literature connecting β-catenin to Wnt signaling (reviewed in [17]).

Adherens junctions regulate the proper assembly of desmosomes in addition to other adhesive structures like tight junctions [18]. While early data highlighted post-translational mechanisms by which cadherins controlled the maturation of cell-cell contacts [19], recent work indicates a connection between cadherins and the transcriptional regulation of tight junction components. Taddei et al. [20] provide evidence that VE-cadherin modulates claudin-5, a key component of tight junctions, at the transcriptional level by reducing nuclear β-catenin levels and stimulating the Akt-dependent phosphorylation and dissociation of FoxO1 from the claudin-5 promoter. The resulting up-regulation of claudin-5 by VE-cadherin only occurs in confluent cultures, highlighting the ability of cadherins to transduce extracellular information into intracellular signaling events.

Regulation of cytoskeletal components and cell polarity

Establishing mechanically sound cell junctions requires active re-organization and attachment of cytoskeletal elements at the cell membrane. Cadherins regulate this process not only by recruiting adapters which associate with cytoskeletal components such as the actin binding proteins α-catenin and α-actinin, but also by recruiting ancillary components which promote the active polymerization, de-polymerization and re-organization of cytoskeletal building blocks. For example, a recent model suggests that by raising the local concentration of α-catenin monomers at cell-cell contacts, E-cadherin promotes the formation of α-catenin dimers which preferentially inhibit Arp2/3 actin remodeling and lamellipodia formation [21]. Abe et al. [22] suggest that E-cadherin/catenin complexes link to the actin cytoskeleton through EPLIN (epithelial protein lost in neoplasm). Not only does EPLIN offer a physical link between cadherins and actin, it also prevents de-polymerization, ensuring the maintenance of a stable adhesive belt in epithelial cells near the apical surface.

Their ability to recruit and modulate cytoskeletal components has implicated cadherins in the development of spatial cues during cell polarization, illustrated recently in a mammalian model by Lechler et al. [23]. Cadherins also contribute to the definition of apical and basolateral membrane domains by acting as docking sites for vesicles bearing the Sec6/8 complex and their protein cargo, thereby assuring that surface proteins are directed to their proper domain within the membrane [24]. The role of cadherins in establishing and coordinating planar cell polarity in tissue, however, has been most thoroughly studied in Drosophila and Caenorhabditis elegans. Extending beyond the establishment of polarity within a cell, Chen et al. [25] demonstrate that homodimers of the atypical cadherin Flamingo serve as conduits of polarity information between adjacent cells. Localized in adherens junctions of the wing, Flamingo proteins recruit the polarity factor ‘Frizzled’, and instruct counterpart Flamingo proteins in the apposing cell to recruit a different polarity factor, ‘Vang’. Ultimately, this phenomenon results in the asymmetric distribution of Frizzled and Vang within cells and the alignment of neighboring cells with respect to their Frizzled/Vang axis. This finding has been corroborated in mammals by Devenport and Fuchs [26], who show that the murine counterparts of Flamingo and Vang, Celsr1 and Vangl2 respectively, are required for proper orientation of hair follicles in the developing embryonic epidermis. The structural and post-translational mechanisms underlying the bidirectional transfer of polarity information by Flamingo homodimers remain unknown, as does the potential role of intermediate, cytoplasmic binding partners. In addition to Flamingo, Saburi et al. [27] implicate the protocadherin Fat in the maintenance of tissue polarity by demonstrating that mice harboring inactivated Fat4 develop cystic kidney disease stemming from defects in oriented cell division.

Regulation of signaling pathways

Aside from regulating structural events, cadherins modulate a number of classic signaling cascades. Studies evaluating the capacity of cadherins to affect cellular signaling events have predominantly focused upon their ability to sequester and alter the signaling capacity of armadillo proteins such as B-catenin and p120. Recently, a desmosomal relative of p120, plakophilin-2, was shown to form complexes with protein kinase C alpha (PKCα) and desmoplakin in a manner that not only affected desmoplakin assembly into desmosomes but also altered phosphorylation of PKC substrates [28]. As plakophilins are thought to interact with desmosomal cadherins [29-31], this data indicates a possible link between cadherins and global PKC signaling events. Tunggal et al. [15] connect cadherins to atypical PKC signaling by demonstrating that knocking out epidermal E-cadherin hinders tight junction formation. They hypothesize that the defect may stem from mislocalized Rac (the small GTP-binding protein) and PKC. Data derived from Drosophila models has expanded the connection between signaling and cadherins to include atypical cadherins, demonstrating, for example, that Fat cadherin regulates cellular proliferation and tissue size by modulating the Hippo tumor suppressor pathway [32].

In addition, a large body of literature has arisen pertaining to cadherins associating with growth factor receptors at the cell surface and regulating downstream signaling cascades. Recent examples include a study by Theisen et al. [33] demonstrating that N-cadherin promotes cell migration in a carcinoma cell line by complexing with the sodium-hydrogen exchanger regulator factor (NHERF), an activator of PDGFR-β (platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta). In confluent endothelial cell cultures, the engagement of VE-cadherin at the membrane enhances its interaction with VEGFR-2 (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2). This interaction prevents receptor internalization, limiting its ability to enter a cytoplasmic signaling pool where it is known to promote proliferation through p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation [34]. Likewise, independent of other cell contacts, the binding of cells to E-cadherin coated beads inhibits EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) signaling and consequently, cell growth [35]. These studies highlight the capacity of cadherins to regulate contact inhibition and are consistent with a large body of data suggesting that the loss or mis-expression of certain cadherin isoforms, in a process termed cadherin-switching, participates in carcinogenesis [36].

The role of cadherins in cancer has done much to illuminate a connection to cellular signaling events, however, the participation of cadherins in other pathologies has proven informative as well. Pemphigus is an autoimmune disease in which antibodies target desmoglein ectodomains, resulting in a loss of keratinocyte adhesion and epidermal blistering. The defect does not entirely involve steric disruption of adhesive dimerization by the antibody, but also relies upon p38-mediated Rho inhibition, since activators of Rho abrogate the adhesive defect both in vitro and ex vivo [37].

Future directions

How cadherins are integrated with other mechanical and chemical signaling pathways to drive developmental and pathogenic processes, such as cancer, will continue to be an intensely studied question in the future. For example, regulatory loops involving cadherins and integrin-mediated cell-matrix adhesion have emerged as important integrators of information within the tissue microenvironment. Yano et al. [38] provide evidence that disruption of FAK (focal adhesion kinase) and paxillin, two well-known participants in integrin signaling, mitigates the recruitment of N-cadherin to sites of cell-cell adhesion. Communication in the reverse direction may occur as well. Endothelial VE-cadherin functions as a scaffold for PECAM-1 (platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1) and VEGFR-2, which together form a mechanosensing-complex capable of transducing shear force into integrin-activating phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling events. In turn, integrin activation drives the nuclear factor κβ (NF-κβ) inflammatory response to abnormal shear forces common in early stages of atherosclerosis [39]. Furthermore, VE-cadherin mediates a Rac-dependent proliferative response to stretch; a subject that is highlighted in an emerging area of literature that connects cadherins to the regulation of mechanotransduction [40]. Atypical cadherins also participate in this process, particularly in the ear, where cadherin-23 and protocadherin-15 have been linked to certain forms of human deafness [41]. In conclusion, future studies will continue to heighten our appreciation of the mechanistic diversity by which cadherins serve as powerful regulators of fundamental cellular processes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Sergey Troyanovsky and Dr Spiro Getsios for their helpful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript. The authors are supported by grants from the NIH to K Green (NIAMS and NCI) and R Harmon (T32 GM08061), the Tiecke-Sowers Fellowship in Pathology (B Desai) and the JL Mayberry Endowment (K Green).

Abbreviations

- EPLIN

epithelial protein lost in neoplasm

- HAV Motif

His-Ala-Val motif

- PKCα

protein kinase C alpha

- VEGFR-2

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be found at: http://F1000.com/Reports/Biology/content/1/13

References

- 1.Nagar B, Overduin M, Ikura M, Rini JM. Structural basis of calcium-induced E-cadherin rigidification and dimerization. Nature. 1996;380:360–4. doi: 10.1038/380360a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stemmler MP. Cadherins in development and cancer. Mol Biosyst. 2008;4:835–50. doi: 10.1039/b719215k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boggon TJ, Murray J, Chappuis-Flament S, Wong E, Gumbiner BM, Shapiro L. C-cadherin ectodomain structure and implications for cell adhesion mechanisms. Science. 2002;296:1308–13. doi: 10.1126/science.1071559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 8.7 ExceptionalEvaluated by Robert Liddington 24 Apr 2002, Vance Lemmon 25 Apr 2002, Carlos Ibanez 5 Jun 2002, Charles Streuli 6 Jun 2002, Jia-huai Wang 11 Jun 2002, David Stokes 28 Jun 2002

- 4.Patel SD, Ciatto C, Chen CP, Bahna F, Rajebhosale M, Arkus N, Schieren I, Jessell TM, Honig B, Price SR, Shapiro L. Type II cadherin ectodomain structures: implications for classical cadherin specificity. Cell. 2006;124:1255–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 3.0 RecommendedEvaluated by Larry Zipursky 19 May 2006

- 5.Nollet F, Kools P, van Roy F. Phylogenetic analysis of the cadherin superfamily allows identification of six major subfamilies besides several solitary members. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:551–72. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nose A, Nagafuchi A, Takeichi M. Expressed recombinant cadherins mediate cell sorting in model systems. Cell. 1988;54:993–1001. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niessen CM, Gumbiner BM. Cadherin-mediated cell sorting not determined by binding or adhesion specificity. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:389–99. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.6 Must ReadEvaluated by Nick Brown 30 Jan 2002, Kathleen J Green 5 Feb 2002, Vance Lemmon 12 Feb 2002

- 8.Shi Q, Chien YH, Leckband D. Biophysical properties of cadherin bonds do not predict cell sorting. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28454–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802563200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prakasam AK, Maruthamuthu V, Leckband DE. Similarities between heterophilic and homophilic cadherin adhesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15434–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606701103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 4.8 Must ReadEvaluated by Christopher Chen 21 Feb 2007, Thomas Friedman 1 May 2007

- 10.Syed SE, Trinnaman B, Martin S, Major S, Hutchinson J, Magee AI. Molecular interactions between desmosomal cadherins. Biochem J. 2002;362:317–27. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chitaev NA, Troyanovsky SM. Direct Ca2+-dependent heterophilic interaction between desmosomal cadherins, desmoglein and desmocollin, contributes to cell-cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:193–201. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foty RA, Steinberg MS. The differential adhesion hypothesis: a direct evaluation. Dev Biol. 2005;278:255–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.0 Must ReadEvaluated by Jonathan Slack 13 Apr 2005

- 13.Green KJ, Simpson CL. Desmosomes: new perspectives on a classic. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2499–515. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larue L, Ohsugi M, Hirchenhain J, Kemler R. E-cadherin null mutant embryos fail to form a trophectoderm epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8263–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tunggal JA, Helfrich I, Schmitz A, Schwarz H, Gunzel D, Fromm M, Kemler R, Krieg T, Niessen CM. E-cadherin is essential for in vivo epidermal barrier function by regulating tight junctions. Embo J. 2005;24:1146–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 3.0 RecommendedEvaluated by Kathleen J Green 15 Apr 2005

- 16.Uemura M, Nakao S, Suzuki ST, Takeichi M, Hirano S. OL-Protocadherin is essential for growth of striatal axons and thalamocortical projections. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1151–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.0 Must ReadEvaluated by Frans Van Roy 29 Oct 2007

- 17.Bienz M. beta-Catenin: a pivot between cell adhesion and Wnt signalling. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R64–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gumbiner B, Stevenson B, Grimaldi A. The role of the cell adhesion molecule uvomorulin in the formation and maintenance of the epithelial junctional complex. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1575–87. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis JE, Wahl JK, 3rd, Sass KM, Jensen PJ, Johnson KR, Wheelock MJ. Cross-talk between adherens junctions and desmosomes depends on plakoglobin. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:919–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.4.919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taddei A, Giampietro C, Conti A, Orsenigo F, Breviario F, Pirazzoli V, Potente M, Daly C, Dimmeler S, Dejana E. Endothelial adherens junctions control tight junctions by VE-cadherin-mediated upregulation of claudin-5. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:923–34. doi: 10.1038/ncb1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.6 Must ReadEvaluated by Dietmar Vestweber 29 Jul 2008, Eric Beyer 8 Aug 2008, Talila Volk 14 Aug 2008, Kathleen J Green with Bhushan Desai 8 Sep 2008

- 21.Drees F, Pokutta S, Yamada S, Nelson WJ, Weis WI. Alpha-catenin is a molecular switch that binds E-cadherin-beta-catenin and regulates actin-filament assembly. Cell. 2005;123:903–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 11.2 ExceptionalEvaluated by Rong Li 6 Dec 2005, Kenneth Yamada 16 Dec 2005, Mariann Bienz 20 Dec 2005, Frans Van Roy 20 Dec 2005, William A Muller 9 Jan 2006, Michel Labouesse 25 Jan 2006, Marie-France Carlier 25 Jan 2006, Kathleen J Green 6 Feb 2006, Carien Niessen 3 May 2006

- 22.Abe K, Takeichi M. EPLIN mediates linkage of the cadherin catenin complex to F-actin and stabilizes the circumferential actin belt. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710504105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 9.0 ExceptionalEvaluated by Frans Van Roy 11 Jan 2008

- 23.Lechler T, Fuchs E. Asymmetric cell divisions promote stratification and differentiation of mammalian skin. Nature. 2005;437:275–80. doi: 10.1038/nature03922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 8.2 ExceptionalEvaluated by David Bilder 14 Sep 2005, Sander van den Heuvel 19 Sep 2005, Kenneth Zaret 3 Nov 2005, Carien Niessen 23 Nov 2005

- 24.Yeaman C, Grindstaff KK, Nelson WJ. Mechanism of recruiting Sec6/8 (exocyst) complex to the apical junctional complex during polarization of epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:559–70. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen WS, Antic D, Matis M, Logan CY, Povelones M, Anderson GA, Nusse R, Axelrod JD. Asymmetric homotypic interactions of the atypical cadherin flamingo mediate intercellular polarity signaling. Cell. 2008;133:1093–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 3.0 RecommendedEvaluated by Deborah Andrew 4 Jul 2008

- 26.Devenport D, Fuchs E. Planar polarization in embryonic epidermis orchestrates global asymmetric morphogenesis of hair follicles. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1257–68. doi: 10.1038/ncb1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saburi S, Hester I, Fischer E, Pontoglio M, Eremina V, Gessler M, Quaggin SE, Harrison R, Mount R, McNeill H. Loss of Fat4 disrupts PCP signaling and oriented cell division and leads to cystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1010–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 3.2 RecommendedEvaluated by David Strutt 10 Jul 2008, Ken Irvine 18 Jul 2008

- 28.Bass-Zubek AE, Hobbs RP, Amargo EV, Garcia NJ, Hsieh SN, Chen X, Wahl JK, 3rd, Denning MF, Green KJ. Plakophilin 2: a critical scaffold for PKC alpha that regulates intercellular junction assembly. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:605–13. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonne S, Gilbert B, Hatzfeld M, Chen X, Green KJ, van Roy F. Defining desmosomal plakophilin-3 interactions. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:403–16. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X, Bonne S, Hatzfeld M, van Roy F, Green KJ. Protein binding and functional characterization of plakophilin 2. Evidence for its diverse roles in desmosomes and beta -catenin signaling. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10512–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108765200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith EA, Fuchs E. Defining the interactions between intermediate filaments and desmosomes. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1229–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.5.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willecke M, Hamaratoglu F, Kango-Singh M, Udan R, Chen CL, Tao C, Zhang X, Halder G. The fat cadherin acts through the hippo tumor-suppressor pathway to regulate tissue size. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2090–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Theisen CS, Wahl JK, 3rd, Johnson KR, Wheelock MJ. NHERF links the N-cadherin/catenin complex to the platelet-derived growth factor receptor to modulate the actin cytoskeleton and regulate cell motility. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:1220–32. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-10-0960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lampugnani MG, Orsenigo F, Gagliani MC, Tacchetti C, Dejana E. Vascular endothelial cadherin controls VEGFR-2 internalization and signaling from intracellular compartments. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:593–604. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200602080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perrais M, Chen X, Perez-Moreno M, Gumbiner BM. E-cadherin homophilic ligation inhibits cell growth and epidermal growth factor receptor signaling independently of other cell interactions. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2013–25. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 3.0 RecommendedEvaluated by Dietmar Vestweber 25 Apr 2007

- 36.Wheelock MJ, Shintani Y, Maeda M, Fukumoto Y, Johnson KR. Cadherin switching. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:727–35. doi: 10.1242/jcs.000455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waschke J, Spindler V, Bruggeman P, Zillikens D, Schmidt G, Drenckhahn D. Inhibition of Rho A activity causes pemphigus skin blistering. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:721–7. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.0 Must ReadEvaluated by Giulio Gabbiani 18 Dec 2006

- 38.Yano H, Mazaki Y, Kurokawa K, Hanks SK, Matsuda M, Sabe H. Roles played by a subset of integrin signaling molecules in cadherin-based cell-cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:283–95. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.7 Must ReadEvaluated by Douglas DeSimone 23 Jul 2004, Christopher Turner 29 Jul 2004, Michael Schaller 16 Aug 2004, Rudy Juliano 14 Oct 2004, Paola Chiarugi 23 Nov 2004

- 39.Tzima E, Irani-Tehrani M, Kiosses WB, Dejana E, Schultz DA, Engelhardt B, Cao G, DeLisser H, Schwartz MA. A mechanosensory complex that mediates the endothelial cell response to fluid shear stress. Nature. 2005;437:426–31. doi: 10.1038/nature03952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 9.8 ExceptionalEvaluated by Dietmar Vestweber 27 Sep 2005, Christopher Marshall 4 Oct 2005, Mark Ginsberg 24 Nov 2005

- 40.Liu WF, Nelson CM, Tan JL, Chen CS. Cadherins, RhoA, and Rac1 are differentially required for stretch-mediated proliferation in endothelial versus smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2007;101:e44–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.158329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kazmierczak P, Sakaguchi H, Tokita J, Wilson-Kubalek EM, Milligan RA, Muller U, Kachar B. Cadherin 23 and protocadherin 15 interact to form tip-link filaments in sensory hair cells. Nature. 2007;449:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature06091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 8.0 ExceptionalEvaluated by Guy Richardson 5 Oct 2007, Peter Gillespie 8 Oct 2007

- 42.Gayet O, Labella V, Henderson CE, Kallenbach S. The b1 isoform of protocadherin-gamma (Pcdhgamma) interacts with the microtubule-destabilizing protein SCG10. FEBS Lett. 2004;578:175–9. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hebbard LW, Garlatti M, Young LJ, Cardiff RD, Oshima RG, Ranscht B. T-cadherin supports angiogenesis and adiponectin association with the vasculature in a mouse mammary tumor model. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1407–16. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hug C, Wang J, Ahmad NS, Bogan JS, Tsao TS, Lodish HF. T-cadherin is a receptor for hexameric and high-molecular-weight forms of Acrp30/adiponectin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10308–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403382101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schreiner D, Muller K, Hofer HW. The intracellular domain of the human protocadherin hFat1 interacts with Homer signalling scaffolding proteins. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:5295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]