Abstract

Using a generalized Brownian ratchet model that accounts for the interactions of actin filaments with the surface of Listeria mediated by proteins like ActA and Arp2/3, we have developed a microscopic model for the movement of Listeria. Specifically, we show that a net torque can be generated within the comet tail, causing the bacteria to spin about its long axis, which in conjunction with spatially varying polymerization at the surface leads to motions of bacteria in curved paths that include circles, sinusoidal-like curves, translating figure eights, and serpentine shapes, as observed in recent experiments. A key ingredient in our formulation is the coupling between the motion of Listeria and the force-dependent rate of filament growth. For this reason, a numerical scheme was developed to determine the kinematic parameters of motion and stress distribution among filaments in a self-consistent manner. We find that a 5–15% variation in polymerization rates can lead to radii of curvatures of the order of 4–20 μm, measured in experiments. In a similar way, our results also show that most of the observed trajectories can be produced by a very low degree of correlation, <10%, among filament orientations. Since small fluctuations in polymerization rate, as well as filament orientation, can easily be induced by various factors, our findings here provide a reasonable explanation for why Listeria can travel along totally different paths under seemingly identical experimental conditions. Besides trajectories, stress distributions corresponding to different polymerization profiles are also presented. We have found that although some actin filaments generate propelling forces that push the bacteria forward, others can exert forces opposing the movement of Listeria, consistent with recent experimental observations.

Introduction

It has long been known that cell motility is driven by actin polymerization (1,2). In addition to cell locomotion, the movement of certain pathogens, such as Listeria monocytogenes, is also driven by actin polymerization (3,4). By hijacking the actin machinery of the host cell, these pathogens are able to propel themselves by forming actin-rich comet tails, where propulsive forces are generated by the unidirectional polymerization of actin filaments (5), as illustrated in Fig. 1, left. Actin-based motility has been one of the most studied subjects in biophysics and biochemistry in the past few decades due to the pivotal role of cell motility in so many important biological processes, such as wound healing and immune response. In addition, actin polymerization provides a way to convert chemical energy stored in biological systems into mechanical energy, which might have profound implications for the future development of miniature-scale medical devices capable of moving in our body to deliver drugs or conduct medical procedures, since actin is well known to be one of the most abundant proteins in human cells.

Figure 1.

Schematic plot of a moving Listeria. (Left) The bacteria are propelled by polymerization of actin filaments. (Right) The geometry of Listeria is simplified as a rod with a square cross section.

Significant progress has been made in identifying different proteins involved in the formation of the actin comet tail, as well as their distinct roles in the polymerization process. For example, it has been found that the only surface protein necessary for Listeria motility is ActA. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that microspheres coated with ActA can grow actin comet tails and move in cytoplasmic extracts in the same way as the pathogens (6,7). Experimental evidence also suggests that ActA accelerates the growth of actin filaments by attracting profilin, a protein that is believed to be able to deliver monomeric actin to the filament barbed ends (8). It is interesting that the distribution of ActA on the bacterial surface has been found to be nonuniform: instead, the density of ActA reaches its maximum at one pole of the pathogen and decreases gradually when moving away from that pole (9,10). However, ActA will aggregate at both poles in a dividing bacteria, presumably due to the spatially nonuniform creation/destruction of these proteins, so that the two old poles will have the highest ActA concentration after division (10,11). Several studies (10,12) have been conducted to examine the effect of spatial variations in ActA density on the movement of Listeria.

Theoretically, several mechanisms have been proposed to explain force generation by polymerization. Maybe the most well known of these is the so-called elastic Brownian ratchet (EBR) model (13,14), where thermal excitations are assumed to be large enough to bend the actin filament and hence create a gap between its tip and the load surface, which allows continuous polymerization to take place. No interaction between the filament and the load surface was considered in the EBR formulation. However, recent experiments have convincingly demonstrated that the actin comet tail is actually attached to the Listeria surface (15,16). To account for this important finding, Mogilner and Oster (17) presented a modified EBR model in which bonding between the actin filament and the ActA/Arp2/3 complex on the load surface was allowed. Besides Brownian ratchet, a molecular-motor-based end-tracking mechanism has also been proposed by Dickinson and co-workers to explain force generation by actin polymerization (18,19).

In addition to these microscopic formulations, Gerbal et al. (20) constructed a macroscopic model of Listeria propulsion where the actin network is treated as a continuous medium and insertion of actin monomers is assumed to induce elastic deformations in the gel. This model can successfully predict, among several other phenomena, the widely observed hopping motion of Listeria, but it seems to be unable to explain recent experimental observations that propelling forces can also be generated on a flat surface (21,22), as surface curvature is essential for the build-up of elastic energy in this formulation.

On the simulation side, the Monte Carlo method has been used by various researchers to investigate issues like the growth of actin networks (23) and the symmetry breaking of actin clouds (24). A computational model based on molecular mechanics, developed by Alberts and Odell (25), seems to be able to reproduce the saltatory motion of Listeria observed in experiments. In addition, molecular dynamics simulations of actin-driven propulsion have been conducted by Lee and Liu (26).

Recently, we proposed a generalized EBR (GEBR) model where the problem is formulated as the Brownian motions of particles in a potential field (27). Important features like the nucleation and capping of filament tips, as well as the interactions between the tips and the load surface, are taken into account in this formulation in a very simple manner. It has been shown that predictions from the GEBR model agree very well with a variety of experimental results. Details of this model will be given below.

Despite the aforementioned efforts, several intriguing experimental observations remain to be explained theoretically. For example, Upadhyaya and co-workers (28) found that the forces generated within the actin comet tail are not uniform, and that, instead, propelling forces that push the actin-driven vesicle forward are induced by polymerizing filaments at the outer part of the comet tail while forces opposing the vesicle movement are generated in the middle of the tail. Dickinson and Purich (29) studied this problem by assuming that the filament growth is limited by the diffusion of actin monomers. Their model indeed reproduced the teardrop shape of the actin-driven vesicle observed in experiments; however, the stress profile they found is a fairly evenly distributed one, in contrast to what Upadhyaya et al. (28) suggested. Also, it has been convincingly demonstrated that when confined within a plane, Listeria can move along different trajectories, such as circles, sinusoidal-like curves, translating figure eights, and serpentine shapes, etc. (30,31). Rutenberg and Grant (32) suggested that the random placement of polymerizing filaments behind the pathogen is enough to induce observable curvatures in its path. Recently, an empirical description has been proposed to explain how different trajectories can be achieved kinematically (31). However, a theory is still lacking that would connect fascinating Listeria motions with microscopic polymerization details. Another interesting observation is that moving Listeria actually spins around its long axis (33), which implies that in addition to a propelling force, a torque must be generated by actin polymerization as well, a conclusion that has also been drawn from the study on the dynamic trajectories of moving Listeria (31). However, the focus of the existing microscopic or macroscopic models is to find out how a propelling force is generated by polymerizing filaments. As such, they are inherently unable to capture the spinning of the bacteria, as pointed out in a recent review article by Mogilner (34).

Aiming to address these outstanding issues, we present here a microscopic model to describe the motion of actin-driven Listeria based on the GEBR formulation. The goal is to establish a theoretical framework that relates the macroscopic Listeria movements to microscopic polymerization details such as the polymerization rate profile and the actin network structure in the comet tail. Specifically, we show how a net torque can be generated within the comet tail and how such a torque in conjunction with spatially varying polymerization at the surface can lead to the motion of bacteria in curved paths observed in recent experiments.

Force Generation by Polymerization

The first task is to examine how propelling forces necessary for Listeria movement can be generated by polymerizing filaments. It is well known that Listeria has a capsule shape (Fig. 1, left). To simplify the analysis here, we treat Listeria as a rod with a square cross section (Fig. 1, right). The length of the rod is taken to be b = 2 μm, and the half-width of the square is assumed to be a = 0.4 μm (5). We also put the origin of our reference frame on the center of the interface between the Listeria and the actin comet tail such that the x axis is normal to the interface. As mentioned earlier, in most experiments conducted, the movement of Listeria was confined within a plane. Hence, without losing any generality, the Listeria is assumed here to be constrained to move within the xy plane only (Fig. 1, right). Following the GEBR formulation, in the reference frame that moves with a velocity, V, equivalent to the growth speed of the filament network, in the negative x direction, the Brownian motions of the filament tips can be described by (27)

| (1) |

where p(x, t) is the normalized probability distribution for a large ensemble of identical filament tips, kT is the thermal energy, D is the diffusion coefficient of the tip, h is the source (or sink) distribution representing the generation (or elimination) of tips, and U is the total energy stored in each filament when the tip is at location x. All the parameters and variables used here are gathered in Table S1 in the Supporting Material. If nucleation and capping of tips are neglected, then the effects of polymerization and depolymerization can be taken into account by a source distribution, h, as

| (2) |

and

| (3) |

where δ is the projected actin monomer length, K and Koff are the polymerization and depolymerization rates, respectively. Physically, Eqs. 2 and 3 indicate that polymerization can only take place when the gap between the tip and the load surface is larger than the actin monomer size, δ, and addition of a monomer causes the tip to change its position from x to x – δ, whereas the tip position jumps from x to x + δ after depolymerization. The potential energy, U, can be expressed as

| (4) |

Here represents the bending energy stored in the filament. x0 is the tip position in the undeformed configuration, which is unknown and must be solved as part of the solution. is the effective spring constant of filaments, where λ is the persistence length of actin, l is the so-called free-end length of the filament, and θ is the inclined angle of the filament (14,19). corresponds to the interaction energy between the tip and the load surface, which was introduced in light of recent evidence that the actin comet tail is actually attached to the Listeria surface (15,16). The parameter Cb physically describes the depth of the potential well, and σ represents the approximate width of the well. Basic physics tells us that the most important quantities of a potential well are its depth and width; as long as these two parameters are fixed, the actual shape of the well should not significantly affect the outcome, similar to the enforced breaking of a molecular bond, as discussed in Evans and Ritchie (35). The speed at which the reference frame moves should be identical to the filament growth speed, that is,

| (5) |

where depolymerization has been neglected, since in most practical cases, polymerization reaction is much faster than the dissociation of monomers. At steady state, a closed-form solution to Eq. 1 can be found from which the average propelling force, f, induced by a single filament, is

| (6) |

where p(0) is the value of p(x) at x = 0. An important assumption in the above model is that all filaments polymerize at the same rate, so that the velocity of the actin-propelled cargo is equal to the polymerization speed in Eq. 5. However, as mentioned earlier, it has been convincingly demonstrated that the actin-based motility of Listeria is directed by the surface protein ActA, whose distribution on the bacteria surface is not uniform and is actually regulated by various biological processes (for example, cell division). Hence, it is conceivable that the macroscopic polymerization rate might vary spatially at the Listeria surface. In the next section, we explore the implications of such spatially varying polymerization on the movement of the pathogen.

Listeria Movement

Recall that the Listeria is confined to move within the xy plane, so its only admissible motions are linear translation in the x direction and rotations around both z and x axes (Fig. 1, right). We proceed by first neglecting the spinning of the bacteria around its long axis, i.e., the x axis. As shown in Eqs. 5 and 6, the propelling force generated by each filament can be determined numerically once the local polymerization rate and filament growth speed are known; hence, f can be treated as a function of K and V, that is,

| (7) |

Notice that in general the polymerization rate and filament growth speed may not necessarily be spatially uniform behind the Listeria. Consequently, we expect that f can vary with y and z as well. Here, to understand the effects of spatially varying polymerization rates, we first assume that everything is uniform in the z direction, that is, all variables depend on y only. As such, the linear speed, as well as the angular velocity, of Listeria can be determined as

| (8) |

and

| (9) |

respectively, where ρ is the areal density of filaments, V0 is the linear velocity of Listeria, and ωz is the angular velocity in the z direction (Fig. 1, right). α and β are two constants representing the viscous effect against the translation and rotation of the bacteria, respectively. Notice here that the movement of Listeria is assumed to be viscosity-dominant. At steady state, the filament growth speed must be identical to the moving velocity of Listeria surface locally, that is,

| (10) |

Thus, for any given polymerization rate distribution K(y), V0, and ωz must be self-consistently determined from Eqs. 8 and 9 with the help of Eqs. 7 and 10. Obviously, if polymerization is uniform behind Listeria, then there will be no rotation, i.e., ωz = 0, and the problem reduces to that considered in Lin (27). Now, let us examine what will happen if a perturbation is added to the uniform polymerization field. Specifically, we will consider two cases where the perturbation is either symmetric or asymmetric.

Symmetric perturbation

Let us first consider cases where polymerization rate remains symmetric with respect to the xz plane. Assume that

| (11) |

where K0 can be interpreted as the average polymerization rate and δK is the magnitude of the perturbation. Since the perturbation in K is symmetric, we expect the propelling force distribution, f, to be so as well, and hence, according to Eq. 9, ωz must vanish here.

Based on direct measurements reported in the literature, as well as reasonable estimations, the values of all the parameters used here are gathered in Table S2 (see Supporting Material for details). To further simplify the analysis, we assume that the Listeria is driven by 25 polymerizing filaments that are uniformly distributed behind the bacteria with a spacing of ∼200 nm, a reasonable value. We must point out that although the values of various parameters might affect the calculation results to a certain extent, we believe that the main features of the problem, demonstrated below, should be rather robust.

An iterative scheme is developed here to determine the kinematic parameters of motion, as well as the stress distribution among filaments, for a given polymerization profile. Basically, we start with initial guesses of the linear and angular velocities of Listeria, from which the filament growth profile can be obtained through Eq. 10. After that, propelling forces generated by each filament are calculated from Eq. 6, based on which the corresponding translational and rotational velocities of the bacteria can be determined by Eqs. 8 and 9. Notice that these velocities may deviate from the initial guesses, in which case we make a new guess based on standard Newton's method, as detailed in Press et al. (36). These steps will be repeated until the calculated velocities agree with the guesses. The flowchart of the scheme is shown in Fig. S1. We point out that this self-consistent scheme, handling the coupling of motion and force generation, can be applied to systems that involve arbitrary numbers of filaments.

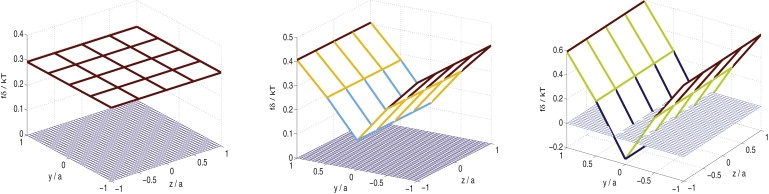

Choosing Cb = 3 and σ/δ = 0.15, the propelling force distributions, corresponding to δK/K0 = 0, 0.25 and 0.75, are shown in Fig. 2. It is clear that filaments at the outer edge, where polymerization is fast, generate higher propelling forces than those in the middle, where polymerization is relatively slow. Furthermore, when the difference in polymerization rate between the outside and inside is large enough, the inner filaments can actually be under tension, i.e., they can generate negative propelling forces. This finding is interesting, because observations by Upadhyaya et al. (28) suggest that the inner part of the actin comet tail indeed generates forces opposing the movement of an actin-propelled vesicle. Hence, the work presented here might provide a plausible explanation for this phenomenon. As mentioned earlier, since the polymerization profile is symmetric in this case, no rotation will be generated and the Listeria is expected to move along a straight line. The normalized Listeria velocity, V0δ/D, has been found to be around 6.5 × 10−3 for all three cases (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Propelling force distribution among filaments arranged in a 5 × 5 array. At force distributions of δK/K0 = 0 (left), δK/K0 = 0.25 (middle), and δK/K0 = 0.75 (right), the normalized Listeria velocities are V0δ/D = 6.5 × 10−3, V0δ/D = 6.6 × 10−3, and V0δ/D = 6.9 × 10−3, respectively.

Asymmetric perturbation

Next, let's turn our attention to the situation where the perturbation in polymerization rate is asymmetric with respect to the x – z plane. We proceed by assuming

| (12) |

Choosing the same parameter values as before, the force distribution corresponding to δK/K0 = 0.25 and 0.75 is shown in Fig. 3. Again, we can see that filaments in the region where polymerization is fast tend to generate larger propelling forces. Also, the force profile becomes asymmetric in this case, which leads to the rotational motion of Listeria. Using our self-consistent numerical scheme, the linear and angular velocities were found to be V0δ/D = 6.5 × 10−3 and ωzaδ/D = 8.5 × 10−4 for δK/K0 = 0.25, whereas these two quantities change to V0δ/D = 6.6 × 10−3 and ωzaδ/D = 2.8 × 10−3 for δK/K0 = 0.75. Obviously, the magnitude of the perturbation in polymerization rate significantly affects how fast Listeria rotates but has negligible influence on the linear speed of bacteria, which is not unexpected, since the average polymerization rate remains unchanged after the perturbation is applied.

Figure 3.

Propelling force distribution among filaments arranged in a 5 × 5 array for δK/K0 = 0.25 (left) and δK/K0 = 0.75 (right).

As a result of the simultaneous linear and rotational motions of Listeria, the trajectory traced out by the pathogen becomes a circle. It can easily be shown that the radius of such a circle is

| (13) |

Hence, the Listeria is expected to move along a circle with radius R = 3 μm for δK/K0 = 0.25 and R = 0.9 μm for δK/K0 = 0.75. R as a function of δK/K0 is shown in Fig. 4. Clearly, as expected, R decreases monotonically with increasing δK. It is interesting to note that experimental observations suggest that Listeria can move along circles with radii ranging from ∼3 μm (31) to >10–20 μm (16). In light of Fig. 4, our results suggest that a 5–20% perturbation in the polymerization rate is large enough to generate such circular trajectories.

Figure 4.

Radius of the circular trajectory of Listeria as a function of the magnitude of the asymmetric perturbation in polymerization rate.

As mentioned before, any nonuniformity in the distribution of ActA on the bacteria surface should effectively introduce a perturbation in the macroscopic polymerization profile. It is reasonable to believe that such a moderate (∼5–15%) perturbation in polymerization rate can indeed be generated in realistic experimental conditions, which, in return, drives the pathogen to move in circles, as observed. In addition, the polymerization rate is expected to be proportional to the local concentration of actin monomers, consequently, any spatial variation in the actin monomer density will definitely affect the actual polymerization profile, which might explain how filaments in the middle of the comet tail tend to generate negative propelling forces (28). Basically, the monomer concentration at the center of the comet tail should be lower than that at the outer edge, since more actin can diffuse to those regions from the surroundings, which seems to be supported by observations that under certain circumstances, the comet tail is actually hollow (37). However, we must also point out that several other studies have suggested that actin monomer depletion in the comet tail is highly unlikely (38,39). Thus, actin diffusion may not be an issue here at all, but the question is open.

Spinning Motion of Listeria

As pointed out earlier, another admissible motion of Listeria, when confined within the xy plane, as shown in Fig. 1, right, is the spinning about its long axis, i.e., the x axis. To see how such motion can be generated, let us first revisit force generation by a polymerizing filament. Notice that the interaction potential, Ui, was assumed to depend only on x, i.e., the normal separation between the tip and the load surface (see Eq. 4). As a result, only the propulsive force along the x direction, given by Eq. 6, is predicted to be generated by polymerization. However, as mentioned earlier, it is commonly believed that the tip interacts with the load surface through direct binding between ActA and actin or via the Arp2/3 complex, which can bind to both the tip and the bacteria surface (40). Consequently, the interaction potential between the tip and the load surface should also depend on the relative displacement in the tangential direction, which, similar to the normal separation, is likely to deform the bond formed between the tip and the Arp2/3 complex. As such, the expression of Ui(x) should be modified to

| (14) |

where r is the total distance of the filament tip from the load surface (Fig. 5, left). In this case, the propelling force generated by the filament becomes (see Supporting Material for details)

| (15) |

In addition, a tangential force,

| (16) |

will also be induced. The generation of such tangential forces is a natural consequence of Eq. 14, where Ui is assumed to depend on the tangential displacement between the tip and the load surface. Note that the direction of this tangential force τ depends on the orientation of the filament. For example, this force is in the positive y direction in the configuration shown in Fig. 5, left. However, τ will be pointing in the z direction if the filament lies within the xz plane instead of the xy plane, as in Fig. 5, left.

Figure 5.

(Left) Diagram showing the deformation of the filament. The dashed line represents the undeformed filament and the solid line corresponds to the deformed filament. (Right) A reference frame x′y′z′ is introduced that spins along with the Listeria.

Thus, in general the torque Tx, in the x direction, generated by all filaments can be calculated as

| (17) |

where is the vector from the origin of the reference frame to the filament tip. At this point, it is instructive to consider the actual structure of the actin comet tail. If the orientations of working filaments, i.e., filaments that hit the load surface, within the comet tail are totally random, then Tx, defined in Eq. 17, is expected to be zero, since the directions of tangential forces induced by different filaments are also random (Fig. 6 a). On the other hand, the magnitude of Tx reaches its maximum when the structure becomes totally correlated, that is, the working filaments are organized in such a way that is orthogonal to everywhere, similar to that in a torsional bar (see Fig. 6 c). A persistent orientation correlation among filaments can be induced by the nonuniform distribution of the ActA/Arp2/3 complex on the bacteria surface, or might arise from the fact that once Listeria starts to move, the growth of filament can become energetically more favorable in some orientations than in others, which ultimately breaks the randomness of the network. However, the mechanisms that could lead to such a symmetry breaking remain to be elucidated in a systematic manner.

Figure 6.

Back view of the working filaments in the comet tail (upper panels) and the corresponding tangential force distributions (lower panels). (a) Random network (ɛ = 0). (b) Partially correlated network (ɛ = 0.2). (c) Totally correlated network (ɛ = 1).

To simplify the analysis, a parameter ɛ is introduced here so that Tx defined in Eq. 17 can be rewritten as

| (18) |

Obviously, ɛ = 0 corresponds to a random structure, whereas ɛ = 1 represents a totally correlated filament network. Hence, ɛ can be interpreted as a parameter characterizing the randomness of the actin network. Due to the appearance of the torque Tx, the Listeria is expected to spin around the x axis. Similar to Eq. 9, the angular velocity, ωx, corresponding to this spinning motion can be determined by

| (19) |

where γ is a viscous parameter associated with the spinning motion of the pathogen. Based on the geometry of Listeria, it is reasonable to believe that the value of γ should be comparable to that of β. Here, the value of is chosen to be 1000. A second coordinate system x′y′z′, introduced here, spins along with the Listeria, whereas the original frame, xyz, is chosen to move with the pathogen without any spinning (Fig. 5, right). As before, the movement of Listeria is assumed to be confined within the xy plane. Consider the configuration where the bacteria has rotated with an angle ωxt, as shown in Fig. 5, right: if the polymerization again is assumed to be asymmetric with respect to the x′z′ plane in this case (recall that the nonuniformly distributed ActA will spin with the pathogen), then the moment induced is actually in the z′ direction, with the magnitude given by the term on the lefthand side of Eq. 9. Note that the correlation factor, ɛ, does not appear in the expression of this moment because, unlike the tangential force, the propelling force, f, defined in Eq. 15, is always in the negative x direction, irrespective of which plane (for example, the x′y′ or x′z′ plane) the filament is in. The y-direction component of this moment will be balanced by the walls which constrain the Listeria to move in the xy plane only, whereas the z component can be expressed as

| (20) |

As such, it is easy to conclude that the bacteria will rotate around the z axis with an angular velocity of cos(ωxt)ωz, where ωz is the same as that defined in Eq. 9. Based on these observations, the bacteria movement can be found to be governed by

| (21) |

where X and Y represent the coordinates of the moving Listeria in a stationary reference frame (see Supporting Material). The bacteria trajectory can then be obtained by simple integration of Eq. 21. Note that V0, ωz, and ωx can be determined from Eqs. 8, 9, and 19, respectively, once the polymerization profile and the comet tail structure are prescribed.

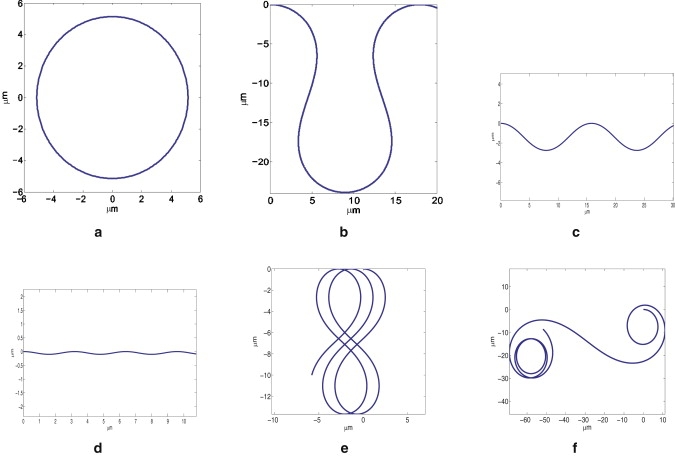

Again, assume that the perturbation in polymerization rate takes the asymmetric form and the Listeria is propelled by 25 filaments. Choosing and other parameter values, as before, the pathogen trajectories under different conditions are shown in Fig. 7. The input values of K, δK, and ɛ, as well as the computed Listeria velocity, V0, corresponding to the different trajectories shown in Fig. 7, are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 7.

Listeria trajectories under different conditions.

Table 1.

Parameters for Listeria trajectories in Fig. 7

| Figure label | K0 (s−1) | δK/K0 (%) | ɛ | V0 (μm/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 261 | 17.5 | 0 | 0.27 |

| b | 261 | 17.5 | 0.053 | 0.27 |

| c | 261 | 17.5 | 0.2 | 0.27 |

| d | 261 | 17.5 | 1 | 0.27 |

| e | 155 | 35.0 | 0.087 | 0.16 |

| f | 145 | 12.5 | 0.0066 | 0.15 |

For K = 261 s−1 and δK/K = 17.5%, Fig. 7, a–d, shows how the bacteria trajectory varies with respect to the actin network structure. Basically, since no spinning motion will be generated when the filament orientations are totally random (Fig. 6 a), the trajectory is just a circle if ɛ = 0, as shown in Fig. 7 a. When ɛ increases slightly to 0.053, the trajectory takes a serpentine shape (Fig. 7 b). A high degree of correlation among filament orientations causes the Listeria to move along sinusoidal-like (or S-shaped) paths with decreasing amplitude as ɛ increases (Fig. 7, c and d). This is not unexpected, because large ɛ leads to high spinning angular velocity; consequently, the moment Tz defined in Eq. 20 changes signs rapidly, which ultimately results in the diminishing amplitude of the curved paths. Note that a connection between the Listeria trajectory and the actual actin network, like those shown in Fig. 6, a–c, has been established here. Fig. 7, e and f, show two other scenarios where the trajectory shapes are a translating figure eight and a spiral, respectively. We must point out that all trajectories predicted here have indeed been observed in experiments. For example, trajectories similar to those shown in Fig. 7, a–e, have been reported by Shenoy et al. (31), whereas the spiral illustrated in Fig. 7 f closely resembles that observed by Gerbal et al. (16).

Up to this point, all filaments have been assumed to run into the load surface with the same angle (35°), which certainly is unrealistic, given the complexity of the three-dimensional actin network (41). To see the effect of variations in filament angle on the results, we have also conducted simulations by choosing filament angles that follow a normal distribution with a mean of 35° and standard deviations of 5° and 10°, respectively. The results are shown in Table S3, from which it is clear that fluctuations in filament angle change our model predictions only slightly. We also want to point out that the GEBR formulation provides the force generated by each filament in an average sense; however, it is reasonable to believe that fluctuations in filament force, similar to those in filament angle, will not affect the results in any significant manner.

Conclusions

On the basis of the GEBR mechanism proposed recently (27), a microscopic model is developed here to study the movement of Listeria propelled by actin polymerization. A key ingredient in our formulation is the coupling between the filament growth and Listeria motion. For this reason, a numerical scheme is introduced to determine the force distribution among filaments and bacteria movement in a self-consistent manner. The main findings of this study are summarized as follows.

Spatial variation of polymerization rate leads to the nonuniform distribution of propelling forces generated by polymerizing filaments. Filaments with a higher polymerization rate (locally) produce larger forces pushing the Listeria forward, whereas smaller, or even negative, propelling forces will be generated by filaments in slower polymerization regions.

If polymerization is fast on one side of the comet tail and slow on the other, a moment will be generated, causing the Listeria to rotate while moving forward, which eventually leads to a curved bacteria trajectory. Furthermore, we found that only a moderate perturbation (∼5–15%) in the polymerization profile is needed to induce the curvatures observed in typical Listeria trajectories.

By considering the realistic bonding between the filament tip and the ActA-Arp2/3 complex on the Listeria surface, we conclude that a tangential force is also likely to be induced by the polymerizing filament. Consequently, a net torque that causes the pathogen to spin around its long axis can be generated by the comet tail depending on the filament orientations within it.

The degree of correlation among filament orientations in the comet tail strongly affects the movement of Listeria. By choosing reasonable parameter values, we found that most trajectories observed in experiments can be reproduced by our model with only a very low degree of correlation, <10%. This might provide a reasonable explanation for why Listeria can travel along totally different paths under seemingly the same experimental conditions, as small fluctuations in filament orientation, as well as polymerization rate, can easily be introduced by various factors.

Several important aspects of the problem have been neglected here but certainly warrant future investigation. For one thing, as in many models of actin motility (e.g., those of Mogilner and Oster (14,17)), we only consider filament free ends here, and the rest of the network is assumed to be rigid. Also, as the polymerization process progresses, the actin network itself is likely to evolve via processes like filament growth, branching, and severing, etc., so a more realistic formulation should take into account the deformability, as well as the structural evolution, of the comet tail and address the interplay between these processes and Listeria motion. However, we do not anticipate that this kind of more detailed calculation will reveal qualitatively new physics relevant to the curvature of the trajectories studied here. In addition, the Listeria surface was treated as flat here, because we expect that a hemispherical surface will lead to the same conclusions, provided that there are spatial variations in polymerization rates and correlations in filament orientations across the surface. Actually, using the approach we have developed here, it is possible to work out the trajectories of Listeria with a capsule shape. However, in that case one needs to take into account variations in the directions of filament forces, as well as filament angles, introduced by the hemispherical geometry, recalling that the normal component of filament force is always along the surface normal direction locally. In addition, Eq. 10. which relates filament growth to the motion of Listeria, needs to be modified accordingly. All these facts will make the formulation less transparent and the implementation mathematically more involved. Nevertheless, if detailed information on ActA distribution or filament orientations is available from experiments, this task can be pursued in the future.

Despite the limitations mentioned above, we feel that our model successfully establishes a connection between the macroscopic movement of Listeria and microscopic polymerization details like the polymerization profile and the comet tail structure. Predictions from this model also compare favorably with a variety of experimental observations. We hope that this formulation can provide a theoretical framework for further studies in which more realistic features can be added.

Acknowledgments

Y.L. is grateful for support from the Seed Funding Programme for Basic Research from The University of Hong Kong (Project No. 200809159003). V.B.S. acknowledges support through a grant from the National Science Foundation (No. CMMI-0825185) and a Solomon Faculty Research Grant from Brown University.

Contributor Information

Yuan Lin, Email: ylin@hku.hk.

V.B. Shenoy, Email: Vivek_Shenoy@brown.edu.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Preston T.M., King C.A., Hyams J.S. Blackie; Glasgow: 1990. The Cytoskeleton and Cell Motility. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Theriot J.A., Mitchison T.J. Actin microfilament dynamics in locomoting cells. Nature. 1991;352:126–131. doi: 10.1038/352126a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanger J.M., Sanger J.W., Southwick F.S. Host cell actin assembly is necessary and likely to provide the propulsive force for intracellular movement of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect. Immun. 1992;60:3609–3619. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.9.3609-3619.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Theriot J.A., Mitchison T.J., Portnoy D.A. The rate of actin-based motility of intracellular Listeria monocytogenes equals the rate of actin polymerization. Nature. 1992;357:257–260. doi: 10.1038/357257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tilney L.G., Portnoy D.A. Actin filaments and the growth, movement, and spread of the intracellular bacterial parasite, Listeria monocytogenes. J. Cell Biol. 1989;109:1597–1608. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.4.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cameron L.A., Footer M.J., Theriot J.A. Motility of ActA protein-coated microspheres driven by actin polymerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:4908–4913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron L.A., Svitkina T.M., Borisy G.G. Dendritic organization of actin comet tails. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:130–135. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith G.A., Theriot J.A., Portnoy D.A. The tandem repeat domain in the Listeria monocytogenes ActA protein controls the rate of actin-based motility, the percentage of moving bacteria, and the localization of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein and profilin. J. Cell Biol. 1996;135:647–660. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.3.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kocks C., Hellio R., Cossart P. Polarized distribution of Listeria monocytogenes surface protein ActA at the site of directional actin assembly. J. Cell Sci. 1993;105:699–710. doi: 10.1242/jcs.105.3.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rafelski S.M., Theriot J.A. Bacterial shape and ActA distribution affect initiation of Listeria monocytogenes actin-based motility. Biophys. J. 2005;89:2146–2158. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.061168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rafelski S.M., Theriot J.A. Mechanism of polarization of Listeria monocytogenes surface protein ActA. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;59:1262–1279. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rafelski S.M., Alberts J.B., Odell G.M. An experimental and computational study of the effect of ActA polarity on the speed of Listeria monocytogenes actin-based motility. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009;7:e1000434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peskin C.S., Odell G.M., Oster G.F. Cellular motions and thermal fluctuations: the Brownian ratchet. Biophys. J. 1993;65:316–324. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81035-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mogilner A., Oster G. Cell motility driven by actin polymerization. Biophys. J. 1996;71:3030–3045. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79496-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo S.C., McGrath J.L. Steps and fluctuations of Listeria monocytogenes during actin-based motility. Nature. 2000;407:1026–1029. doi: 10.1038/35039544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerbal F., Laurent V., Prost J. Measurement of the elasticity of the actin tail of Listeria monocytogenes. Eur. Biophys. J. 2000;29:134–140. doi: 10.1007/s002490050258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mogilner A., Oster G. Force generation by actin polymerization II: the elastic ratchet and tethered filaments. Biophys. J. 2003;84:1591–1605. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74969-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dickinson R.B., Purich D.L. Clamped-filament elongation model for actin-based motors. Biophys. J. 2002;82:605–617. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75425-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickinson R.B., Caro L., Purich D.L. Force generation by cytoskeletal filament end-tracking proteins. Biophys. J. 2004;87:2838–2854. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.045211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerbal F., Chaikin P., Prost J. An elastic analysis of Listeria monocytogenes propulsion. Biophys. J. 2000;79:2259–2275. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76473-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwartz I.M., Ehrenberg M., McGrath J.L. The role of substrate curvature in actin-based pushing forces. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:1094–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Upadhyaya A., van Oudenaarden A. Actin polymerization: forcing flat faces forward. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:R467–R469. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlsson A.E. Growth of branched actin networks against obstacles. Biophys. J. 2001;81:1907–1923. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75842-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dayel M.J., Akin O., Mullins R.D. In silico reconstitution of actin-based symmetry breaking and motility. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alberts J.B., Odell G.M. In silico reconstitution of Listeria propulsion exhibits nano-saltation. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee K.-C., Liu A.J. New proposed mechanism of actin-polymerization-driven motility. Biophys. J. 2008;95:4529–4539. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.134783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin Y. Mechanics model for actin-based motility. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2009;79:021916. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.79.021916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Upadhyaya A., Chabot J.R., van Oudenaarden A. Probing polymerization forces by using actin-propelled lipid vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:4521–4526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0837027100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dickinson R.B., Purich D.L. Diffusion rate limitations in actin-based propulsion of hard and deformable particles. Biophys. J. 2006;91:1548–1563. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.082362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soo F.S., Theriot J.A. Large-scale quantitative analysis of sources of variation in the actin polymerization-based movement of Listeria monocytogenes. Biophys. J. 2005;89:703–723. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.051219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shenoy V.B., Tambe D.T., Theriot J.A. A kinematic description of the trajectories of Listeria monocytogenes propelled by actin comet tails. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8229–8234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702454104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rutenberg A.D., Grant M. Curved tails in polymerization-based bacterial motility. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2001;64:021904. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.64.021904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robbins J.R., Theriot J.A. Listeria monocytogenes rotates around its long axis during actin-based motility. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:R754–R756. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mogilner A. Mathematics of cell motility: have we got its number? J. Math. Biol. 2009;58:105–134. doi: 10.1007/s00285-008-0182-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evans E., Ritchie K. Strength of a weak bond connecting flexible polymer chains. Biophys. J. 1999;76:2439–2447. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77399-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Press W.H., Teukolsky S.A., Flannery B.P. 2nd ed. Cambridge University; Cambridge, United Kingdom: 1992. Numerical Recipes in FORTRAN: The Art of Scientific Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plastino J., Olivier S., Sykes C. Actin filaments align into hollow comets for rapid VASP-mediated propulsion. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:1766–1771. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mogilner A., Edelstein-Keshet L. Regulation of actin dynamics in rapidly moving cells: a quantitative analysis. Biophys. J. 2002;83:1237–1258. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73897-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akin O., Mullins R.D. Capping protein increases the rate of actin-based motility by promoting filament nucleation by the Arp2/3 complex. Cell. 2008;133:841–851. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boujemaa-Paterski R., Gouin E., Pantaloni D. Listeria protein ActA mimics WASp family proteins: it activates filament barbed end branching by Arp2/3 complex. Biochemistry. 2001;40:11390–11404. doi: 10.1021/bi010486b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Svitkina T.M., Verkhovsky A.B., Borisy G.G. Analysis of the actin-myosin II system in fish epidermal keratocytes: mechanism of cell body translocation. J. Cell Biol. 1997;139:397–415. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.2.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.