Abstract

The purpose of this study was to screen burn patients for alcohol use disorders to identify those at increased risk for repeat injury and adverse effects of alcohol use. We examined associations of at-risk drinking and dependence symptoms as measured by a formal screening tool and blood alcohol concentration (BAC) to guide further screening, treatment, and research. We hypothesized that the majority of drinkers would not have symptoms of alcohol dependence, that BAC would be inadequate to screen for alcohol disorders, and that at-risk drinkers would be more likely to be unemployed and uninsured than healthy drinkers. Formal screening of English speakers, age 16 to 75, admitted to the burn service for over 24 hours was conducted for a 6-month period, using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Of the 123 patients eligible for the study, 110 (89.4%) were approached for formal screening, four refused (3.6%), and 13 were missed (10.6%). BAC was obtained in 68 of 110 (61.8%); no patient who reported abstinence had a positive BAC. Of the 106 screened, 34.9% were nondrinkers, 11.3% drank daily or almost daily, and 28.3% binge drank at least monthly (>4 drinks per occasion for men, >3 for women). Of the patients who drank, only eight patients reported one or more sign of dependence in the last year (11.6%). For the group as a whole, 20.9% met Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test criteria for at-risk drinking, with an average BAC of 39.8 mg/dl, (range 0–242 mg/dl). Using BAC of ≥80 mg/dl, only 5.6% of patients would have been identified as at-risk drinkers. Twenty-three percent of patients had no health insurance, 36% of whom were at-risk drinkers compared with 17.3% of insured patients (P < .05). For the group as a whole, 41.8% of patients were unemployed. At-risk drinking did not differ between employed and unemployed patients (24.6% vs 17.8%, P > .05). Among burn patients, formal alcohol screening identified that one in five patients is at risk for further problems from their drinking and that most at-risk drinkers are binge drinkers and do not show signs of dependency. Formal screening identified more at-risk drinkers than BAC. Implications of the screening findings are 1) because most burn patients who drink are binge but not dependent drinkers, alcohol withdrawal should be infrequent, and 2) animal models of alcohol use and burn injury should study acute intoxication and binge exposure. In addition, 3) we would expect burn patients to respond to brief interventions for alcohol use disorders similar to trauma and primary care patients.

The relationship between alcohol and injury, in both the trauma and the burn populations, is well documented.1–5 “Alcoholism” was identified in the 1970s as the number one “predisposing factor to burning.”6 However, we found little published information examining the prevalence of alcohol use disorders in burn patients and the association of alcohol use with demographic characteristics of patients with burn injury. In the acute care setting, assumptions about a patient’s alcohol use tend to be based on blood alcohol concentration (BAC) or on a patient’s general hygiene and behavior.2 It has since been shown that emergency health care providers are unreliable at clinically identifying which patients are acutely intoxicated. Nearly one third of acute intoxications are misdiagnosed because of confounding factors such as mechanical ventilation, neurologic injury, and pharmacologic intervention, showing that more patients are under the influence of alcohol than previously thought.2,7

Before 2007, our Burn service used no objective tool other than the BAC to identify alcohol misuse. In February 2007, formal alcohol screening was implemented via the use of a validated screening questionnaire. The goal of this study was to describe alcohol use disorders in burn patients to identify drinkers at increased risk for repeat injury and ongoing adverse effects of alcohol use. We examined associations of at-risk drinking with BAC and determined the prevalence of alcohol dependence to guide further screening, treatment, and research efforts. We hypothesized that the majority of drinkers would not have symptoms of alcohol dependence and that at-risk drinkers would be more likely to be unemployed and uninsured than drinkers with low-risk alcohol use. The implications of a low rate of alcohol dependence would be a population with a low incidence of alcohol withdrawal and the ability to respond to brief interventions (BI) as a treatment strategy. If the study population of at-risk drinkers were unemployed and uninsured, these demographic characteristics could be used to facilitate in-house interventions rather than relying on referral to outpatient settings the patients may not be able to afford.

METHODS

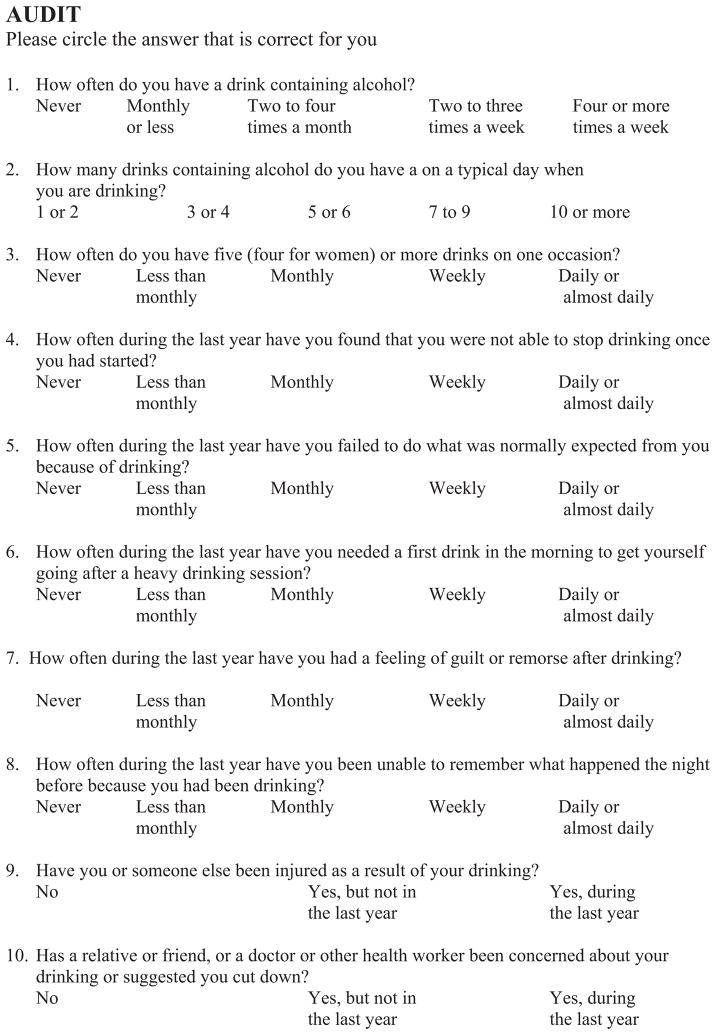

Patients were prospectively screened by a dedicated research nurse and social worker not directly involved in clinical care or medical decision making; the Burn service policy is to obtain BAC on all adult patients admitted with acute burn injury. We examined a cohort of patients spanning the first 6 months of screening from February 2007 through August 2007; only residents of our state were included as this was part of a larger study with long-term follow-up. English speakers, age 16 to 75, admitted to the burn service for more than 24 hours were screened using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). The AUDIT quantifies elements of alcohol consumption and evaluates dependence symptoms and alcohol-related problems. It was developed from a six-country World Health Organization initiative to screen for early at-risk drinkers.8 Early at-risk drinkers are individuals who are at risk for consequences from their alcohol use, such as legal, medical, or social issues, but they have yet to develop symptoms of alcohol dependence. Identifying early at-risk drinkers is essential to improve the success of treating alcohol use disorders before alcohol dependence has developed.9 The AUDIT is a 10-item survey designed to expand the scope of previous screening tools like the CAGE questions—cutting back, annoyance, guilt, and eye-opener or drinking first thing in the morning.10 Alcohol consumption is measured in terms of quantity of use, frequency of use, and frequency of heavy (binge) drinking days. Dependence is identified by inability to stop drinking once started, failure to complete expected tasks, and needing a first drink in the morning to get going. The remaining questions explore adverse events related to drinking and alcohol-related problems. Question no. 3, which asks about heavy drinking (binge) days, was modified to account for differences in American serving sizes compared with international standards,11 and also to include gender differences to reflect the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism definition of binge drinking. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism defines binge drinking as >4 drinks per occasion for men and >3 drinks per occasion for women usually within a 2-hour period (Figure 1).11 Each of the 10 items is scored from 0 to 4. The total score can range from 0 to 40. A total score of ≥8 for patients aged 21 to 64 identifies people who are already suffering harm from their alcohol use (eg, burned while intoxicated) or at risk for further consequences.8 For patients aged <21 or ≥65, a score of 4 is the suggested threshold to define at-risk drinking.11–13 The term at-risk drinkers will be used throughout the article to identify patients with these scores. When using age-specific at-risk drinking scores, the sensitivity of the AUDIT for identifying hazardous and harmful alcohol use has been shown to be 87 to 96% with a specificity of 81 to 98%.8

Figure 1.

Alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software (version 13.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc.). Normally distributed variables were analyzed using t-tests. The χ2 test was used for categorical data.

RESULTS

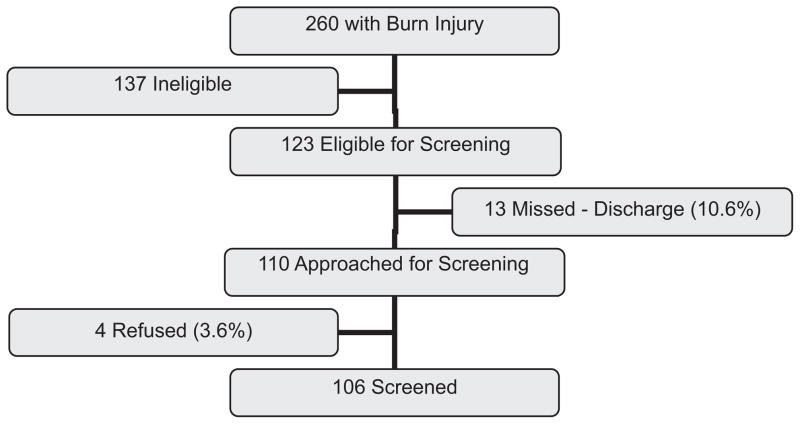

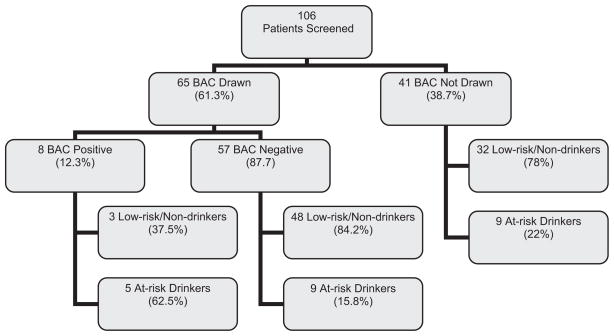

Over the 6-month time period, 260 patients were admitted with burn injury; 124 of those patients were not included because of age (n = 102, 47.7%), out of state residency (n = 6, 2.3%), and language barrier (n = 16, 6.2%). An additional 13 (9.6%) patients were ineligible because of injury severity. One hundred twenty-three patients (47.3%) were eligible for screening. Screening efforts missed 13 patients because of early discharge resulting in a miss rate of 10.6%. Of the 110 (80.9%) people approached for screening, only four refused (3.6%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Recruitment of study population.

Demographics

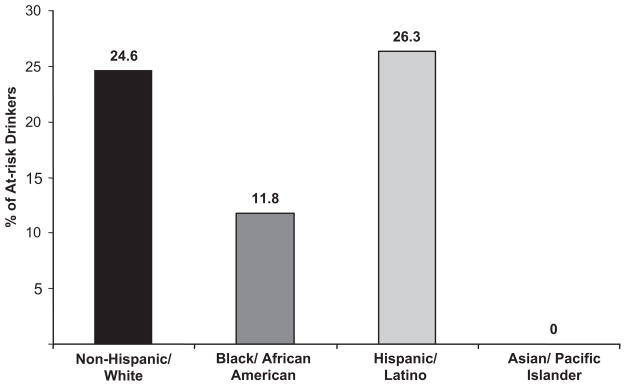

Gender and race/ethnicity distribution of the group are shown in Table 1. Of patients who drank, a significantly larger percentage of men were at-risk drinkers, 27.2% (n = 22) than women at 4% (n = 1) (P < 0.05). Though there seemed to be a higher percentage of non-Hispanic-White at-risk drinkers (24.6%, n = 16) compared with both Black/African Americans (11.8%, n = 2) and Asian/Pacific Islanders (0%, n = 0), there were no statistically significant differences. There was a similar proportion of at-risk drinkers between non-Hispanic-White and Hispanic/Latino patients (24.6% (n = 16) vs 26.3% (n = 5)) (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Demographics of screened population

| Mean age (yr) | 41.4 ± 15.3 |

| Sex n (%) | |

| Male | 84 (76.4) |

| Female | 26 (23.6) |

| Race/ethnicity n (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic-White | 68 (61.8) |

| Black/African American | 18 (16.4) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 19 (17.3) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 5 (4.5) |

| Employed | 51 (46.4) |

| Insured | 84 (76) |

Figure 3.

Percentage of at-risk drinkers per racial/ethnic group.

Insurance and Employment

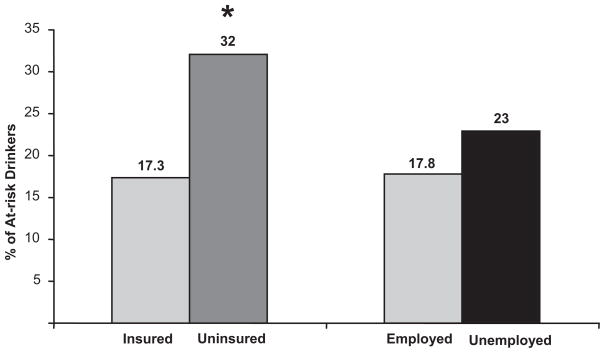

Twenty-three percent (n = 26) of patients had no form of health insurance, and among uninsured patients, 36% (n = 9) were at-risk drinkers compared with 17.3% (n = 14) of insured patients (P < .05). Unemployment among the group as a whole was 41.8% (n = 46). At-risk drinking did not differ between employed and unemployed patients (24.6% vs 17.8%, n = 15 vs 8, P > .05) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Percentage of at-risk drinkers per group. *P < .05 compared with insured group.

Patterns of Alcohol Use

Of the 106 patients screened, 69 (65.1%) were drinkers and 37 (34.9%) were nondrinkers. One in five (20.9%, n = 23) met AUDIT criteria for at-risk drinking, 11.3% (n = 12) drank daily or almost daily, and 28.3% (n = 30) binge drank at least monthly. Among the 69 patients who drank, 33.3% (n = 23) were at-risk drinkers with 28.9% (n = 20) binge drank at least monthly, and 8 (11.6%) reported one or more sign of dependence in the last year (Table 2), with 7.2% (n = 5) reporting any sign in the last month.

Table 2.

Alcohol use disorders in burn patients who drink as measured by AUDIT*

| At-risk drinking n (%) | 23 (33.3) |

| Binge drinking | 30 (43.5) |

| Dependent drinking | 8 (11.6) |

Total number of patients who drank = 69. Patients can belong to more than one group. At-risk drinkers = AUDIT Score ≥8 for age 21–64, score ≥4 for ages >21 or ≥65. Binge drinking is >4 drinks per occasion for men and >3 drinks per occasion for women. Percentages shown are monthly binge drinkers and those drinkers with one or more dependence symptom in the last year.

BAC Results

BACs were obtained in 68 of the 110 eligible patients (61.8%); no patient who reported abstinence had a positive BAC. Using BAC of 80 mg/dl (the legal definition of impaired driving), only 5.6% (n = 6) of patients would have been identified as at-risk drinkers, less than one third of the 20.9% identified by the AUDIT (Figure 5). The at-risk drinkers’ BAC ranged from 0 to 242 mg/dl with an average of 39.8 mg/dl compared with 7.5 mg/dl in the low-risk drinking group (P < .05).

Figure 5.

At-risk drinking by blood alcohol concentration (BAC). At-risk drinkers = AUDIT Score ≥8 for age 21 to 64, score ≥4 for ages 21 or ≥65. BAC positive is any level >0 mg/dl.

DISCUSSION

Among burn patients, formal alcohol screening identified that only 11.6% of burn patients who drink reported one or more sign of dependence in the last year, but one in five patients is at risk for further problems from their drinking and that most at-risk drinkers are binge drinkers. Of the screened population, 65% (95% CI 55.95–74)14 consumed alcohol and 28.9% (95% CI 19.45–36.55)14 binge drank. Comparing these data to state data, 57.8% of state responders reported consuming alcohol and 19.3% of those binge drank in the last month,15 implying that burn patients do not seem more likely to drink than the general population, but may be more likely to binge drink. The sample size of the study population resulted in a wide confidence interval that overlapped the confidence interval for the percentage of people in the state who binge drink. Further studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to see if indeed burn patients are more likely to binge drink and to see if treatment efforts to decrease binge drinking are efficacious.

Rates of dependence vary by institution, but our findings that 11.6% of the study population showed one or more sign of dependency are similar to rates reported in the trauma literature. Trauma patients with any sign of dependence make up less than 20% of the drinking population (Sharp et al, unpublished data, 2008).16,17 However, it is important to note that AUDIT screening is not sufficient to make a full diagnosis of alcohol dependence syndrome. To meet criteria for this diagnosis, as outlined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual version IV, a patient must experience three or more of the seven outlined criteria, in a 12-month period.18 The AUDIT only screens for three of seven criteria. Referral to treatment after intervention is indicated for patients manifesting signs of dependence on AUDIT screening.

It is crucial to emphasize the importance of identifying and treating early at-risk drinkers. Studies have repeatedly shown that injured patients who were intoxicated at the time of their injury have a recurrent injury rate over 40% and, because of their alcohol use disorder, a 2-fold increase in their risk of death from a subsequent injury.19,20 As physicians, we screen our patients for diseases which, when caught early, can be modified to change the natural history and outcomes. When patients are screened for hazardous and harmful drinking, particularly in primary care, trauma, and emergency department settings, there is clear literature to support interventions in order to modify subsequent alcohol use and injury risk. Trauma patients who meet AUDIT criteria for at-risk drinking if given a brief counseling session, otherwise known as a brief intervention, have a decreased number of return emergency department visits, driving under the influence arrests, and on average a 50% decrease in alcohol consumption.21–23 It stands to reason that since burn patients with alcohol use disorders are more likely to be early at-risk drinkers than dependent drinkers, implementing BI in the burn population should yield changes in their alcohol use similar to those seen in trauma populations.

From a manpower and economic standpoint, there is evidence that formal in-house alcohol screening and BI is a feasible treatment scenario.24 In 2005, the American College of Surgeons mandated that all level 1 trauma centers implement screening for alcohol use disorders and have the ability to offer treatment options like BI. Because burn victims are a similar at-risk group, extending BI to burn patients constitutes good comprehensive care. Another facet of the studied population is that 39% of at-risk drinkers do not have health insurance and would not have the means to follow-up for further treatment. Moreover, they would be unlikely to have a primary care provider that could screen for an alcohol use disorder and offer BI. Regulatory groups have seen fit to support this initiative through current procedural terminology (CPT) codes for nonpsychiatric health care providers to submit billing for time spent during formal AUDIT screening and BI.

The implication of low dependence rates in this study is that alcohol withdrawal should be infrequent (Sharp et al, unpublished data, 2008). It has been shown that fewer than 10% of patients who suffer from alcohol withdrawal syndrome will develop the dangerous symptoms associated with withdrawal (eg, autonomic instability, tremor, and delirium). Seizures will occur in less than 3% of patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome.18 Therefore, any prophylactic treatment, other than symptom driven alcohol withdrawal prophylaxis, would result in unnecessary overmedication.

The study showed that the AUDIT identified more at-risk drinkers than BAC alone. This was partially due to failure to measure BAC in some patients, and also because a number of at-risk drinkers had either a low BAC on admission or may not have been drinking on the day of admission. The high percentage of patients in whom the BAC was not drawn is not unusual when compared with similar studies in the trauma population.21 Although we know that a BAC of 80 mg/dl or higher impairs driving, it is not clear what level of BAC should be used to say that people are at risk from their drinking behaviors. In addition, because alcohol is metabolized between the time of injury and BAC determination and because BAC is often missed, it is an inadequate screening tool for alcohol use disorders in this population. Because screening efforts are to be applied to a broad population to identify people at risk for a disease, the presence of alcohol on admission has no impact on our screening efforts. If a patient is sober at the time of the injury, but screens positive for an alcohol use disorder, it is still appropriate to administer BI. Without intervention, this patient continues to be at-risk for consequences/injury secondary to alcohol use, even if alcohol was not a factor in this hospitalization.

Although at-risk drinkers were more likely to be uninsured than the other patients included in this study, they were no more likely to be unemployed. This is likely due to the fact that as early at-risk drinkers, these patients have experienced only minor consequences of their alcohol use. They may be able to maintain some degree of employment, but unable to hold jobs that provide health insurance.

One of the limitations of the study was that patients who were admitted and discharged on the weekends were missed by the current screening protocol. Over the 6-month period only 10% (n = 13) of the eligible population was missed because of discharge before screening. A miss rate of 10% of eligible patients is consistent and acceptable when compared with formal screening protocols at other institutions.21,24

In addition, screening is currently limited to English speakers. However, only 6.2% (n = 16) of patients were ineligible due to language and hence we do not currently employ the staff to administer the AUDIT in other languages. Because the AUDIT is validated in several languages, we would be able to expand our screening to include non-English speakers should the demographics of the burn population change.

For those unfamiliar with the AUDIT, there is likely to be some concern that these are self reported data and therefore are unreliable. It has been shown in both AUDIT and other alcohol research that patients are surprisingly “honest” about their alcohol use in self-reports.25,26 Data from this study supports the population’s honesty; none of our patients who had a positive BAC reported that they were a non-drinker.

CONCLUSION

As hypothesized, rates of alcohol dependence were low, and at-risk drinkers were more likely to be uninsured. Contrary to the hypothesis, employed patients were just as likely to be at-risk drinkers as unemployed patients. BAC seems to be an inadequate indicator of at-risk drinking, and formal alcohol screening for alcohol use disorders is indicated in this high-risk burn population. The low rate of dependence symptoms among at-risk drinkers is a significant indication that burn patients do not require standardized alcohol withdrawal prophylaxis and will benefit from in-house BI. Furthermore, acute intoxication and binge models of alcohol exposure in animal models are more clinically relevant for burn studies than chronic exposure models.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Schermer’s staff: Karen Grimley, MSW and Pamela Van Auken, RN for their tireless data collection, as well as Melanie D. Bird, PhD and David F. Schneider, MD for their thoughtful discussion on this project.

This work was supported by NIH T32 GM08750 (R.L.G.), NIH R01 AA015067 (C.R.S.), NIH R01 AA012034 (E.J.K.), an Illinois Excellence in Academic Medicine Grant (E.J.K.), and the Dr. Ralph and Marian C. Falk Medical Research Trust (R.L.G.), International Association of Fire Fighters Research Grant (J.M.A.).

References

- 1.McGill V, Kowal-Vern A, Fisher SG, Kahn S, Gamelli RL. The impact of substance use on mortality and morbidity from thermal injury. J Trauma. 1995;38:931–4. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199506000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jurkovich GJ, Rivara FP, Gurney JG, Seguin D, Fligner CL, Copass M. Effects of alcohol intoxication on the initial assessment of trauma patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:704–8. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)82783-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thombs BD, Singh VA, Halonen J, Diallo A, Milner SM. The effects of preexisting medical comorbidities on mortality and length of hospital stay in acute burn injury: evidence from a national sample of 31,338 adult patients. Ann Surg. 2007;245:629–34. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000250422.36168.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macdonald S, Cherpitel CJ, DeSouza A, Stockwell T, Borges G, Giesbrecht N. Variations of alcohol impairment in different types, causes and contexts of injuries: results of emergency room studies from 16 countries. Accid Anal Prev. 2006;38:1107–12. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reiland A, Hovater M, McGwin G, Jr, Rue LW, 3rd, Cross JM. The epidemiology of intentional burns. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:276–80. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000216301.48038.F3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacArthur JD, Moore FD. Epidemiology of burns. The burn-prone patient. JAMA. 1975;231:259–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gentilello LM, Villaveces A, Ries RR, et al. Detection of acute alcohol intoxication and chronic alcohol dependence by trauma center staff. J Trauma. 1999;47:1131–5. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199912000-00027. discussion 1135–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption—II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babor TF, Aguirre-Molina M, Marlatt GA, Clayton R. Managing alcohol problems and risky drinking. Am J Health Promot. 1999;14:98–103. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-14.2.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soderstrom CA, Smith GS, Kufera JA, et al. The accuracy of the CAGE, the Brief Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test, and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test in screening trauma center patients for alcoholism. J Trauma. 1997;43:962–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199712000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NIAAA. The physician’s guide to helping patients with alcohol problems. Washington DC: NIAAA; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung T, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Rohsenow DJ, Spirito A, Monti PM. Screening adolescents for problem drinking: performance of brief screens against DSM-IV alcohol diagnoses. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:579–87. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Philpot M, Pearson N, Petratou V, Dayanandan R, Silverman M, Marshall J. Screening for problem drinking in older people referred to a mental health service: a comparison of CAGE and AUDIT. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7:171–5. doi: 10.1080/1360786031000101120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Confidence Interval for Proportions Calculator. [accessed Jan. 2008]; available from http://www.dimensionresearch.com/resources/calculators/conf_prop.html; Internet.

- 15.Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey. [accessed Jan. 2008];2006 available from http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/; Internet.

- 16.Soderstrom CA, Smith GS, Dischinger PC, et al. Psychoactive substance use disorders among seriously injured trauma center patients. JAMA. 1997;277:1769–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunn CW, Donovan DM, Gentilello LM. Practical guidelines for performing alcohol interventions in trauma centers. J Trauma. 1997;42:299–304. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199702000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV) 4. 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sims DW, Bivins BA, Obeid FN, Horst HM, Sorensen VJ, Fath JJ. Urban trauma: a chronic recurrent disease. J Trauma. 1989;29:940–6. discussion 946–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dischinger PC, Mitchell KA, Kufera JA, Soderstrom CA, Lowenfels AB. A longitudinal study of former trauma center patients: the association between toxicology status and subsequent injury mortality. J Trauma. 2001;51:877–84. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200111000-00009. discussion 884–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schermer CR, Moyers TB, Miller WR, Bloomfield LA. Trauma center brief interventions for alcohol disorders decrease subsequent driving under the influence arrests. J Trauma. 2006;60:29–34. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000199420.12322.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schermer CR. Alcohol and injury prevention. J Trauma. 2006;60:447–51. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196956.49282.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sommers MS, Dyehouse JM, Howe SR. Binge drinking, sensible drinking, and abstinence after alcohol-related vehicular crashes: the role of intervention versus screening. Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automot Med. 2001;45:317–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schermer CR. Feasibility of alcohol screening and brief intervention. J Trauma. 2005;59(Suppl 3):S119–S123. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000174679.12567.7c. discussion S124–S133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradley KA, McDonell MB, Bush K, Kivlahan DR, Diehr P, Fihn SD. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions: reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change in older male primary care patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1842–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donovan DM, Dunn CW, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Ries RR, Gentilello LM. Comparison of trauma center patient self-reports and proxy reports on the Alcohol Use Identification Test (AUDIT) J Trauma. 2004;56:873–82. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000086650.27490.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]