Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To provide family physicians with an approach to suicide prevention in youth.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION

A literature review was performed using Ovid MEDLINE with the key words suicide, attempted suicide, and evaluation studies or program evaluation, adolescent.

MAIN MESSAGE

Youth suicide might be prevented by earlier recognition and treatment of mental illness. Family physicians can and should screen for mental illness in youth; there are many diagnostic and treatment resources available to assist with this.

CONCLUSION

Earlier detection and treatment of mental illness are the most important ways family physicians can reduce morbidity and mortality for youth who are contemplating suicide.

Résumé

OBJECTIF

Proposer aux médecins de famille une approche en matière de prévention du suicide chez les jeunes.

SOURCES DES DONNÉES

Une recherche documentaire a été faite à l’aide d’Ovid MEDLINE en utilisant les mots-clés suicide, attempted suicide, ainsi qu’evaluation studies ou program evaluation, adolescent.

MESSAGE PRINCIPAL

On pourrait prévenir le suicide chez les jeunes en reconnaissant et en traitant plus tôt la maladie mentale. Les médecins de famille peuvent et devraient faire le dépistage de la maladie mentale chez les jeunes; il existe de nombreuses ressources sur le diagnostic et les traitements pour les aider à le faire.

CONCLUSION

Une détection et un traitement plus précoces de la maladie mentale sont les moyens les plus importants dont disposent les médecins de famille pour réduire la morbidité et la mortalité chez les jeunes qui envisagent le suicide.

Teen suicide has increased 4-fold in the past 40 years1 and is now the second leading cause of death in this age group.2 The number 1 risk factor for youth suicide is the presence of mental illness.3,4 Because youth do not usually present to their family physicians with psychological symptoms as the chief complaint,5 physicians need to be on alert for symptoms and risk factors that suggest the development of psychiatric illness and suicide risk. This article will review such risk factors and provide information and resources to assist family physicians in assessing and managing youth at risk of suicide and mental illness.

Sources of information

A literature review was performed using Ovid MEDLINE with the key words suicide, attempted suicide, and evaluation studies or program evaluation, adolescent.

Challenges for family physicians

The following case presentation illustrates the complexity of dilemmas presented to family physicians who work with adolescents with mental health concerns. This review of adolescent suicide will equip physicians with an approach to help such patients.

Case description

Sarah, a 16-year-old patient you have not seen in several years, has booked an appointment to discuss starting birth control pills. Sarah’s mother was at the office last week for renewal of antidepressant medication and mentioned that Sarah has been very irritable at home and once yelled, “I might as well be dead!” You know that Sarah’s parent’s divorced last year. While taking Sarah’s blood pressure you notice that she has several scars from superficial cuts to her left wrist. How can you address these issues and determine her risks?

Morbidity and mortality

Canada witnesses more than 500 suicides per year among those 15 to 24 years old, with the next most common cause of death being cancer at 156 deaths per year.6 It has been estimated that for each completed suicide, there are approximately 400 attempts.7 Many high-school students contemplate suicide,3 and with the shortage of pediatric psychiatrists, much of the burden of identifying and treating high-risk youth is placed on family physicians.

Why the rise in youth suicide?

Living with a divorced parent is the single most explanatory variable associated with an increase in youth suicide, regardless of whether the youth is currently living in a single-parent household.7 Although relatively uncommon, contagion behaviour in response to a friend or family member committing suicide can lead to a 2- to 4-fold increase in suicide risk in teens aged 15 to 19.8

The Food and Drug Administration black box warning regarding increased suicidality in youth treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)9 corresponded to a subsequent decrease in both the prescription of these antidepressants and the diagnosis of depression itself.10 Increases in completed suicide were observed internationally in populations where SSRI prescriptions declined.10 Current evidence suggests that the risk of not treating depression outweighs the risk of using SSRIs in this population.11,12 Box 1 provides tips for prescribing SSRIs for youth.13

Box 1. Tips for prescribing antidepressant medication for youth.

The following should be considered when prescribing antidepressants for youth:

|

Adapted from Cheung et al.13

Risk factors

Mental illness is the most important risk factor for adolescent suicide.3,4 The most common precursors to suicide are the presence of a mood disorder, addiction, or a previous suicide attempt.3,4 When multiple risk factors are present, the risk of suicide increases further.4,14 Family physicians working in office settings, walk-in clinics, and emergency departments are poised to identify many of the risk factors for adolescent suicide.

Mental illness

Most serious adult psychiatric illness, including depression, anxiety and substance abuse, starts in the early teens to early twenties.3 There is typically a delay of 10 to 20 years before a diagnosis is made, delaying important and potentially life-saving treatment.3 More than 90% of suicide victims have psychiatric illnesses at the time of their deaths.15–17 It is important to consider mental illness in general, and not just depression, as an important risk factor for suicide.

Previous attempt

Suicidal behaviour in youth tends to repeat itself, with additional attempts or completed suicide often occurring shortly after the index attempt.14,18,19 History of a previous suicide attempt, especially with highly lethal means, confers a 21% risk of committing suicide over the subsequent 5 years, with the highest risk occurring within a month of the initial attempt.18 Patients with drug and alcohol abuse problems, hallucinations, or suicide plans are among those at highest risk of repeated suicidal behaviour.19

Precipitant

There are specific precipitants that tend to precede completed suicides, and assessing physicians should explore this history. The most common triggers for suicidality are a fight with parents and the end of a relationship.20 Other disappointments, rejection, important losses, and financial difficulties can also be triggers.20 An important precipitant of suicidal thoughts in teens is humiliation, in particular, feelings of disgrace and public disparagement.14 Although very little has been published on the subject, the use of social networking websites by teens can affect suicidal behaviour and the opportunity for public humiliation.

Impulsivity

Completed suicide is more likely among teens who act impulsively. Establishing a history of impulsivity is important in predicting which youth need intense supervision or immediate transfer to a safe place for treatment. Impulsivity can manifest as physical aggression, fights at school, and risk-taking activities.21 Substance use can impair judgment and exacerbate impulsivity. An impulsive teen might act quickly on suicidal thoughts.

Family history

A family history of suicide, depression, addiction, and other mental illness is associated with a higher risk of suicide in teens.22 Poor family communication23 and low parental monitoring24 also increase the risk. Family physicians can facilitate and encourage healthy family communication and make referrals for family counseling as necessary.

Physical and sexual abuse

Physical, sexual, and emotional abuse are common among youth who present with suicidal thoughts or behaviour.20,25,26 This type of information should be obtained in a respectful and compassionate manner and be documented in the patient’s chart. One approach that is not overly intrusive is to start off by asking, “Has anything really awful ever happened to you?” This can be followed up with examples or further questioning.

Other risk factors

Teens who attempt suicide are more likely to be in trouble with the police,27 be involved in physical fights,24 demonstrate difficulties in school,28 have poor school functioning,14 lack academic motivation,27 and perceive their academic performances to be poor.29 This latter risk factor is independent of level of intelligence.14,29 Physical illness, particularly a chronic physical illness in relapse, confers an increased risk of suicide.30 Teens who engage in sexual activity are also at higher risk, independent of other risk factors.24 Gay and lesbian teens or those with sexual identity issues are a special risk group.31 Aboriginal youth are 1.5 times more likely to commit suicide than nonaboriginal youth.32

Role of the family physician

Prevention and screening are important, considering that parents are unaware of 90% of suicide attempts made by their teenagers.3 Warning signs for suicide are listed in Box 2.33 Physicians should use chance patient encounters or periodic health examination visits as opportunities for screening for mental illness, hopelessness, and suicidal thoughts.

Box 2. Warning signs for adolescent suicide.

The following are some common warning signs of adolescent suicide:

|

Adapted from the Canadian Mental Health Association.33

Screen for mental illness

Periodic health examination visits are ideal opportunities for physicians to use adolescent questionnaires (eg, www.glad-pc.org on page 18 of the tool kit34) to quickly identify at-risk youth. It is important for physicians to realize that the incidence of mental illness is substantial, even though youth are unlikely to present with psychological issues as their chief complaint. While only 12% of patients aged 15 to 24 present to their family practitioners with psychological complaints, about 50% have clinically significant levels of psychological distress, and 22% have clinically significant levels of suicidal thoughts.5

Discuss confidentiality

Studies clearly indicate that if teens believe that their disclosure of suicidal thoughts could result in a break in confidentiality, they are less willing to divulge personal information.35,36 A physician can introduce this issue by initially explaining that the visit between the teen and physician is confidential; however, if there are any risks of danger to the patient or others, the physician would need to act responsibly.

Address self-harm behaviour

Self-mutilation is associated with serious mental illness and confers a high risk of eventual completed suicide. Patients with borderline personality disorder have a 3% to 10% lifetime risk of eventual suicide.25 Most adult patients with repeated visits for self-mutilation meet criteria for borderline personality disorder.25 Teens often self-mutilate by superficially cutting or burning the skin.37

It is not reasonable to dismiss self-mutilating behaviour as a manipulative or attention-seeking behaviour, as it is associated with serious mental pathology and a considerable lifetime risk of eventual completed suicide.25 Group therapy such as that offered by the Canadian Mental Health Association (www.cmha.ca) can be helpful for such teens.

Assess level of intent

Acts of self-harm might or might not be associated with true intent to commit suicide.37 Physicians need to specifically ask whether the self-harm behaviour was intended to relieve psychological pain or whether there was intention to commit suicide. If they are asked in a calm and sensitive manner, patients are often willing to make this distinction. If there is some ambivalence on the part of the patient, a scale can be used with 0 being no intention and 10 being definite intention to commit suicide. Ultimately, the physician needs to exercise good judgment based on the patient’s situation, symptoms, and risk factors to decide whether the patient’s response and the physician’s calculation of risk are congruent.

Assess reasons for living

A belief that it is acceptable to end one’s life confers a 14-fold increased likelihood of making a suicide plan.38 Suicidal individuals tend to be ambivalent about wanting to live and wanting to die. It is useful for physicians to assess reasons for living, such as responsibility for family, moral objections to suicide, and fear of disapproval. Discussing reasons for living can sometimes be reassuring to both patients and physicians.

Identify and mobilize protective factors

The most important protective factors are social support28 and a sense of family cohesion.39 School connectedness,40 sports involvement,41 and academic achievement can also reduce a teen’s risk.40 Emotional and psychological support from friends and family appears to safeguard against suicide.42 Family physicians can also provide important support to youth who have no one else to turn to or trust. In some cases the physician can mediate disputes and assist patients in working through interpersonal problems.

Reduce access to lethal means

Parents or other care-givers need to be counseled regarding reducing access to lethal means for youth suicide. Such specific counseling has been shown to be effective at influencing the care-giver’s behaviour in this regard.43 Lethal means include medications (prescription and over-the-counter), knives, guns, and ropes. Hanging is the most common method of completed suicide among Canadian adolescents.44

Consider hospitalization if necessary

If it is deemed that there is currently a substantial risk of suicide, a referral can be made to an inpatient psychiatry unit, preferably a youth psychiatry unit. In some cases the physician might need to complete “Form 1: Application by Physician for Psychiatric Assessment” under the Canadian Mental Health Act (form 1 and form 42, the notice of application for psychiatric assessment, are available at www.forms.ssb.gov.on.ca).45,46

Resources for family physicians

There is a paucity of psychiatric services available for youth in Canada. For this reason, family physicians take on much of the responsibility for assessing and caring for youth with mental health needs. The Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recommends 6 child and adolescent psychiatrists per region of 100 000 people, but child and adolescent psychiatrists are in short supply throughout Canada.47 Fortunately, there are many resources available to family physicians to facilitate screening, diagnosis, and management of at-risk youth (Box 3).

Box 3. Resources for physicians, patients, and families.

|

Guidelines

The Guidelines for Adolescent Depression—Primary Care (GLAD-PC)34 were created to address the concerning issue that most adolescent depression was being managed in the primary care setting, not by pediatric or adolescent psychiatrists. The guidelines address the needs of patients aged 10 to 21 years and are intended to provide information about identification, assessment, diagnosis, initial management, treatment, and ongoing management of depression in this population. The guidelines (available at www.glad-pc.org)34 are a start to offering primary care physicians assistance in dealing with this complex population and problem.

Questionnaires

The Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS) adolescent and parent questionnaires, which are available in the GLAD-PC tool kit (www.glad-pc.org on page 18 of the tool kit),34 can be easily completed by patients in the waiting room, saving time and increasing the likelihood of identifying important risk factors for mental illness and suicide even at a quick visit.

Mentorship

The Collaborative Mental Health Network, supported by the Ontario College of Family Physicians, provides mentorship over the telephone for family physicians in need of assistance in managing the mental health concerns of their patients. Such programs offer hope to physicians who want to do more and to patients who would otherwise be unable to access specialized psychiatric care.

Diagnostic criteria

Family physicians can refer to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision,48 to review symptoms of pediatric and adolescent mental illnesses. Physicians should be aware that impulsivity, poor coping skills, and a history of self-harm are signs of potentially serious mental pathology.

Accessing crisis services

Youth crisis services can be accessed by family physicians, patients, and families. Family physicians should be aware of the crisis services available in their communities. Telephone hot-line and online services such as Kids Help Phone (Box 3) can provide an initial assessment and assist with finding resources. Other online resources such as www.ementalhealth.ca and Mental Health Service Information Ontario (www.mhsio.on.ca), as well as the social services telephone directory (dial 211 in the greater Toronto area in Ontario and Edmonton and Calgary in Alberta), are available to help identify local resources.

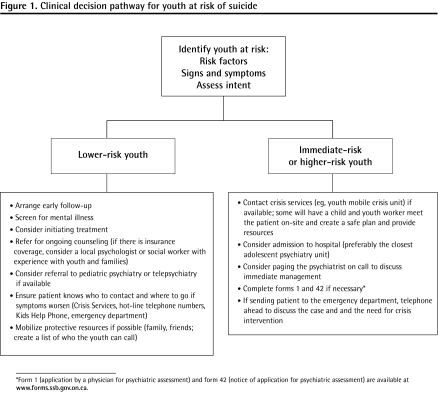

Decision pathway for family physicians

Figure 1 illustrates a decision pathway to help family physicians deal with at-risk youth. The case resolution below gives some specific examples of how the information in this review can be used to help assess and treat youth at risk of suicide.

Figure 1.

Clinical decision pathway for youth at risk of suicide

*Form 1 (application by a physician for psychiatric assessment) and form 42 (notice of application for psychiatric assessment) are available at www.forms.ssb.gov.on.ca.

Case resolution

Sarah is relieved when you ask her if she has been feeling sad and hopeless. She admits to passive suicidal thoughts and elaborates on the stress at home and her anger about her parents’ divorce. She is not using drugs and is not sexually active. There is no history of impulsivity. She says that she has never really wanted to end her life. Upon further questioning, Sarah admits that her mother is actually a caring mom who wants the best for her. She agrees to allow her mother to come in for the last few minutes of her appointment to discuss the above issues. Sarah is willing to see you again for a more thorough review of psychiatric symptoms, and you give her the adolescent questionnaire to complete before her next appointment. You also refer her to a local psychologist, as she has insurance coverage through her mother’s workplace.

Conclusion

Suicide will claim the lives of more young patients than any other disease. Completed suicide is only the tip of the iceberg of the psychosocial pathology that exists for adolescents in crisis. Mental illness is the most important precursor to suicide. Identifying and treating mental illness in youth is an important factor in reducing this risk. There are a growing number of resources available to assist family physicians in identifying, diagnosing, treating, and referring adolescents with mental health concerns.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Savithiri Ratnapalan and Paul Links and No Youth Left Behind, which is a volunteer group of physicians and allied mental health providers working toward enhancing crisis and mental health services for youth and their families in the Barrie area of central Ontario.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Teen suicide is the second leading cause of death among 15- to 24-year-olds. Because youth do not usually present to their family physicians with psychological symptoms as the chief complaint, physicians need to be on alert for symptoms and risk factors that suggest the development of psychiatric illness and suicide risk.

Mental illness is the most important risk factor for adolescent suicide. The most common precursors to suicide are the presence of a mood disorder, addiction, or a previous suicide attempt. When multiple risk factors are present, the risk of suicide increases further. Impulsivity, poor coping skills, and a history of self-harm are signs of potentially serious mental pathology.

Identifying and treating mental illness in youth is an important factor in reducing the risk of suicide. This article highlights a variety of resources available to support family physicians in diagnosing and treating youth at risk of suicide.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Le suicide chez les adolescents représente la deuxième plus importante cause de décès chez les 15 à 24 ans. Parce que les jeunes ne consultent habituellement pas leur médecin de famille précisément pour des symptômes psychologiques, les médecins doivent être attentifs aux symptômes et aux facteurs de risque susceptibles de mener au développement d’une maladie psychiatrique et à un risque de suicide.

La maladie mentale est le plus important facteur de risque de suicide chez les adolescents. Les précurseurs les plus fréquents du suicide sont la présence d’un trouble de l’humeur, une dépendance ou une tentative de suicide antérieure. Lorsque de multiples facteurs de risque sont présents, le risque de suicide augmente encore davantage. L’impulsivité, de faibles aptitudes à faire face à la réalité et des antécédents de blessure volontaire sont des signes d’une pathologie mentale possiblement grave.

L’identification et le traitement de la maladie mentale chez les jeunes représentent d’importants facteurs dans la réduction du risque de suicide. Cet article met en évidence diverses ressources pour aider les médecins de famille à diagnostiquer et à traiter les jeunes à risque de se suicider.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

This article is eligible for Mainpro-M1 credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro link.

Contributors

Both authors contributed to the literature search and to preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Canadian Taskforce on Preventive Health Care . Prevention of suicide. London, ON: Canadian Taskforce on Preventive Health Care; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canada Safety Council [website] Canada’s silent tragedy. Ottawa, ON: Canada Safety Council; 2006. Available from: http://archive.safety-council.org/info/community/suicide.html. Accessed 2010 Jun 16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman RA. Uncovering an epidemic—screening for mental illness in teens. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(26):2717–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beautrais AL. Risk factors for suicide and attempted suicide among young people. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(3):420–36. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lothen-Kline C, Howard DE, Hamburger EK, Worrell KD, Boekeloo BO. Truth and consequences: ethics, confidentiality, and disclosure in adolescent longitudinal prevention research. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(5):385–94. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Statistics Canada . Suicides and suicide rates, by sex and by age group. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2010. Available from: www40.statcan.ca/l01/cst01/hlth66a-eng.htm. Accessed 2010 Jun 16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cutler DM, Glaeser EL, Norberg KE. Explaining the rise in youth suicide. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gould MS, Wallenstein S, Kleinman M. Time-space clustering of teenage suicide. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131(1):71–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Food and Drug Administration [news release] Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration; 2004. FDA launches a multi-pronged strategy to strengthen safeguards for children treated with antidepressant medications. Available from: www.antidepressantsfacts.com/2004-10-15-FDA-Black-Box-SSRIs-suicide.htm. Accessed 2010 Jun 16. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Marcus SM, Bhaumik DK, Erkens JA, et al. Early evidence on the effects of regulators’ suicidality warnings on SSRI prescriptions and suicide in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(9):1356–63. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07030454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibbons RD, Hur K, Bhaumik DK, Mann JJ. The relationship between antidepressant prescription rates and rate of early adolescent suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1898–904. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olfson M, Shaffer D, Marcus SC, Greenberg T. Relationship between antidepressant medication treatment and suicide in adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(10):978–82. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheung AH, Emslie GJ, Mayes TL. The use of antidepressants to treat depression in children and adolescents. CMAJ. 2006;174(2):193–200. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidson S, Joffe RT, Offord DR, Pfeffer CR, editors. Suicide in children and adolescents. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe & Huber Publishers; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleischmann A, Bertolote JM, Belfer M, Beautrais A. Completed suicide and psychiatric diagnoses in young people: a critical examination of the evidence. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75(4):676–83. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Links P. Ending the darkness of suicide [editorial] Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(3):129–30. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roy A. Consumers of mental health services. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;31(Suppl):60–83. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.1.5.60.24222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suokas J, Lonnqvist J. Outcome of attempted suicide and psychiatric consultation: risk factors and suicide mortality during a five-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;84(6):545–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1991.tb03191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapur N, Cooper J, King-Hele S, Webb R, Lawlor M, Rodway C, et al. The repetition of suicidal behavior: a multicenter cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(10):1599–609. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breton JJ, Boyer R, Bilodeau H, Raymond S, Joubert N, Nantel MA. Is evaluative research on youth suicide programs theory-driven? The Canadian experience. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2002;32(2):176–90. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.2.176.24397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Links P. Arthur Sommer Rotenberg Chair in Suicide Studies Professor of Psychiatry Lecture. Assessing and managing suicide risk in psychiatric patients. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canadian Mental Health Association [website] Youth and self injury. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Mental Health Association; 2010. Available from: www.cmha.ca/bins/content_page.asp?cid=3-1036&lang=1. Accessed 2010 Jun 16. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park HS, Koo HY, Schepp KG. Predictors of suicidal ideation for adolescents by gender. Daehan Ganho Haghoeji. 2005;35(8):1433–42. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2005.35.8.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King RA, Schwab-Stone M, Flisher AJ, Greenwald S, Kramer RA, Goodman SH, et al. Psychosocial and risk behavior correlates of youth suicide attempts and suicidal ideation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(7):837–46. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Links PS, Gould B, Ratnayake R. Assessing suicidal youth with antisocial, borderline, or narcissistic personality disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48(5):301–10. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hagedorn J, Omar H. Retrospective analysis of youth evaluated for suicide attempt or suicidal ideation in an emergency room setting. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2002;14(1):55–60. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2002.14.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flouri E, Buchanan A. The protective role of parental involvement in adolescent suicide. Crisis. 2002;23(1):17–22. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.23.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walsh E, Eggert LL. Suicide risk and protective factors among youth experiencing school difficulties. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2007;16(5):349–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2007.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin G, Wait S. Parental bonding and vulnerability to adolescent suicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;89(4):246–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Leo D, Scocco P, Marietta P, Schmidtke A, Bille-Brahe U, Kerkhof AJ, et al. Physical illness and parasuicide: evidence from the European Parasuicide Study Interview Schedule (EPSIS/WHO-EURO) Int J Psychiatry Med. 1999;29(2):149–63. doi: 10.2190/E87K-FG03-CHEE-UJD3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.About.com [website] Chicago, IL: About.com; 2010. Are gay and lesbian youth at high risk for suicide? Available from: http://parentingteens.about.com/cs/gayteens/a/gayyouthsuicide.htm. Accessed 2010 Jun 16. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Suicide prevention evaluation in a Western Athabaskan American Indian Tribe—New Mexico, 1988–1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47(13):257–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.21. Canadian Mental Health Association [website] Youth and suicide. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Mental Health Association; 2010. Available from: www.cmha.ca/bins/content_page.asp?cid=3-101-104&lang=1. Accessed 2010 Jun 16. [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Reach Institute . Guidelines for adolescent depression—primary care (GLAD-PC) New York, NY: The Reach Institute; 2007. Available from: www.glad-pc.org. Accessed 2010 Jun 22. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dervic K, Gould MS, Lenz G, Kleinman M, Akkaya-Kalayci T, Velting D, et al. Youth suicide risk factors and attitudes in New York and Vienna: a cross-cultural comparison. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2006;36(5):539–52. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.5.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.King CA, Kramer A, Preuss L, Kerr DC, Weisse L, Venkataraman S. Youth-nominated support team for suicidal adolescents (version 1): a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(1):199–206. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levenkron S. Cutting: understanding and overcoming self-mutilation. New York, NY: Lion’s Crown Ltd, W.W. Norton & Company Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joe S, Romer D, Jamieson PE. Suicide acceptability is related to suicide planning in U.S. adolescents and young adults. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37(2):165–78. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.2.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chioqueta AP, Stiles TC. The relationship between psychological buffers, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation: identification of protective factors. Crisis. 2007;28(2):67–73. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.28.2.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hall-Lande JA, Eisenberg ME, Christenson SL, Newumark-Sztainer D. Social isolation, psychological health, and protective factors in adolescence. Adolescence. 2007;42(166):265–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKelvey RS, Pfaff JJ, Acres JG. The relationship between chief complaints, psychological distress, and suicidal ideation in 15-24-year-old patients presenting to general practitioners. Med J Aust. 2001;175(10):550–2. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chioqueta AP, Stiles TC. Cognitive factors, engagement in sport, and suicide risk. Arch Suicide Res. 2007;11(4):375–90. doi: 10.1080/13811110600897143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kruesi MJ, Grossman J, Pennington JM, Woodward PJ, Duda D, Hirsch JG. Suicide and violence prevention: parent education in the emergency department. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(3):250–5. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199903000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shaw D, Fernandes JR, Rao C. Suicide in children and adolescents: a 10-year retrospective review. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2005;26(4):309–15. doi: 10.1097/01.paf.0000188169.41158.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ministry of Health . Form 1. Application by physician for psychiatric assessment. Ottawa, ON: Ministry of Health; 2000. Form no. 014-6427-41. Available from: www.forms.ssb.gov.on.ca/mbs/ssb/forms/ssbforms.nsf/GetAttachDocs/014-6427-41~1/$File/6427-41_pdf. Accessed 2010 Jun 22. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ministry of Health . Form 42. Notice to person under subsection 38.1 of the Act of application for psychiatric assessment under section 15 or an order under section 32 of the Act. Ottawa, ON: Ministry of Health; 2000. Form no. 014-1787-41. Available from: www.forms.ssb.gov.on.ca/mbs/ssb/forms/ssbforms.nsf/GetAttachDocs/014-1787-41~1/$File/1787-41_.pdf. Accessed 2010 Jun 22. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry [website] A career in child and adolescent psychiatry. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; 2005. Available from: www.cacap-acpea.org/CareerOpp_About.aspx. Accessed 2010 Jun 16. [Google Scholar]

- 48.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2001. text revision. [Google Scholar]