ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE

To examine the common clinical and behavioural factors that contribute to cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk (ie, attributable risk) among those with type 2 diabetes.

DESIGN

Analysis of data from a larger observational study. Using the validated UK Prospective Diabetes Study risk engine, the primary analysis examined the prevalence and attributable risk of CVD for 4 factors. Multivariable models also examined the association between attributable CVD risk and appropriate self-management behaviour.

SETTING

Twenty primary health care clinics in the South Texas area of the United States.

PARTICIPANTS

A total of 313 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus currently receiving primary care services for their condition.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Prevalence of elevated CVD risk factors (glycated hemoglobin [HbA1c] levels, blood pressure, lipid levels, and smoking status), the attributable risk owing to these factors, and the association between attributable risk of CVD and diet, exercise, and medication adherence.

RESULTS

The mean 10-year CVD risk for the study population (N = 313) was 16.2%, with a range of 6.5% to 48.5% across clinics; nearly one-third of this total risk was attributable to modifiable factors. The primary variable driving risk reduction was HbA1c levels, followed by smoking status and lipid levels. Patients who were carefully engaged in monitoring their diets and medications reduced their CVD risk by 44% and 39%, respectively (P < .03).

CONCLUSION

Patients with diabetes experience a substantial risk of CVD owing to potentially modifiable behavioural factors. High-quality diabetes care requires targeting modifiable patient factors strongly associated with CVD risk, including self-management behaviour such as diet and medication adherence, to better tailor clinical interventions and improve the health status of individuals with this chronic condition.

RÉSUMÉ

OBJECTIF

Examiner les facteurs cliniques et comportementaux courants qui contribuent aux maladies cardiovasculaires (MCV) (c.-à-d. le risque attribuable) chez les personnes atteintes du diabète de type 2.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Analyse des données tirées d’une importante étude observationnelle. À l’aide de l’instrument validé de mesure du risque d’une étude prospective sur le diabète au Royaume-Uni, l’analyse primaire examinait l’association entre le risque attribuable de MCV et un comportement approprié dans la prise en charge de leur santé par les intéressés.

CONTEXTE

Vingt cliniques médicales de soins primaires dans la région du sud du Texas, aux États-Unis.

PARTICIPANTS

Total de 313 patients ayant un diabète de type 2 et recevant actuellement des services de soins primaires pour ce problème de santé.

PRINCIPAUX PARAMÈTRES ÉTUDIÉS

Prévalence des facteurs de risque élevé de MCV (taux d’hémoglobine glycolisée [HbA1c], tension artérielle, taux de lipides et tabagisme), risque attribuable en raison de ces facteurs, et association entre le risque attribuable de MCV et l’alimentation, l’activité physique et la conformité à la médication prescrite.

RÉSULTATS

Le risque médian sur 10 ans de MCV dans la population à l’étude (N = 313) était de 16,2 %, le taux variant de 6,5 % à 48,5 % selon la clinique; près du tiers de ce risque total était attribuable à des facteurs modifiables. La principale variable pouvant amener une réduction du risque était les taux de HbA1c, suivis du tabagisme et des taux de lipides. Les patients qui surveillaient attentivement leur alimentation et leur médicaments pouvaient réduire leur risque de MCV de 44 % et 39 % respectivement (P < ,03).

CONCLUSION

Les patients diabétiques courent un risque considérable de MCV en raison de facteurs comportementaux qu’il est possible de modifier. Des soins de grande qualité pour le diabète exigent de cibler chez les patients les facteurs modifiables fortement associés au risque de MCV, y compris les comportements dans la prise en charge de leur santé comme le respect du régime alimentaire et des médicaments prescrits, pour mieux adapter sur mesure les interventions cliniques et améliorer l’état de santé des personnes souffrant de cette maladie chronique.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a serious but preventable complication of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) that results in substantial disease burden, increased health services use, and higher risk of premature mortality.1 The obesity epidemic in the United States and Canada, as well as in numerous other countries, has unfortunately exacerbated the situation by further increasing the risk of metabolic disorders and diabetes, creating a serious public health issue.2 Managing the numerous risk factors responsible for CVD in T2DM represents an ongoing challenge for primary care clinicians, strongly influencing their decisions about treatment approaches for this complex disease.3 Established risk factors include poor control of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels, systolic blood pressure, and lipid levels, along with age, sex, ethnicity, smoking status, and disease duration.4,5 While the demographic characteristics might be considered fixed factors, others are potentially modifiable through educational efforts that address lifestyle choices and behaviour.

Although some improvements have been made in reducing average HbA1c values for patients with diabetes in the United States over the past few years,6 continued efforts are still warranted. Despite wide dissemination of evidence-based guidelines and the availability of new therapeutic agents, there has been little improvement in other modifiable CVD risk factors, such as blood pressure control, diet, exercise, and treatment adherence. Further, only small improvements in lipid control among patients with T2DM have been observed over the past decade.7–9 Recognizing opportunities for enhanced clinical outcomes, our primary objective for this study was to examine the contribution of common clinical and behavioural factors (ie, attributable risk) to CVD risk. We pursued this aim by assessing both patient-level risk and variation in risk across primary care clinics, as well as by determining the potential benefits of improved control of modifiable risk factors.

METHODS

This study focused on examining attributable risk of CVD, but it is derived from a larger ongoing project examining the quality and intermediate clinical outcomes of care delivered to patients with T2DM across myriad primary care settings. The community health care providers in this study were located in a wide area of South Texas in the United States, and included both urban and rural clinics. Additional details of the primary study design and patient recruitment efforts are provided elsewhere.10 During this naturalistic observational study, 617 patients across 20 primary care clinics were recruited and interviewed. Of those individuals, 424 met the following inclusion criteria: 1) initially received a diagnosis of diabetes at least 1 year before this study; 2) had been with their current physician for at least 1 year; and 3) had received no previous diagnosis of coronary artery disease. This protocol conforms to the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) criteria and remains an appropriate application of their cardiovascular risk engine.11 From this eligible population, 313 patients (73.8%) had complete data on all factors necessary to calculate a 10-year CVD risk, and represented the final sample for this study. Most frequently, the missing data reflected a lack of information about the patient’s age at diabetes onset and duration of the illness. Data on patient characteristics and risk factors were collected by survey and chart abstraction. The study was approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center Institutional Review Board.

The 10-year absolute (or total) risk of fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction was estimated for each patient and averaged for each clinic using the UKPDS risk engine (version 2.0).5 The overall UKPDS risk, calculated using the only risk calculator developed specifically for patients with T2DM, is based on weightings of fixed risk factors (age, sex, ethnicity, duration of diabetes), and 4 potentially modifiable risk factors (HbA1c levels, systolic blood pressure, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C] levels, and smoking status). Two primary outcomes are reported here: First, the absolute risk of a CVD event over the next 10 years using current values for all of the above factors. Second, the attributable or excess risk due to poor control of potentially modifiable risk factors. This attributable risk was calculated by setting each patient-level risk factor at the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommended guideline level,12 if it was not at target, then recalculating the UKPDS risk score. That is, setting the HbA1c level at 7.0 if HbA1c was greater than 7.0, blood pressure at 130/80 mm Hg if higher than that, HDL-C at 45 mg/dL (1.17 mmol/L) if lower than that, and smoking status as “no” if the patient currently smoked.12 The percentage difference between this new score and the absolute risk is the attributable risk—the percentage of CVD risk that was directly associated with potentially modifiable factors. One-way sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine the relative effect of each modifiable factor separately (ie, resetting each risk factor individually as per ADA guidelines). In addition, the ratio of fixed to attributable risk was calculated for each clinic.

Finally, in order to explore the role of several key behavioural practices, a multivariable regression model examined the association between CVD risk (now defined as the dependent variable) and patient report of self-management behaviour regarding personal diet, exercise, and appropriate medication adherence. Separate survey items for each aspect of self-care were assessed with a Likert scale corresponding to the transtheoretical stages of change model (ie, pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, or maintenance stages). Based upon previous published studies using these variables,13–15 we dichotomized all 3 items to signify if the patient reported being in the maintenance stage of change over the past 6 months. The analysis controlled for demographic characteristics and duration of diabetes. These personal or lifestyle practices are not incorporated into the UKPDS risk engine for determining CVD risk, but represent other important, potentially mutable patient-level factors.

RESULTS

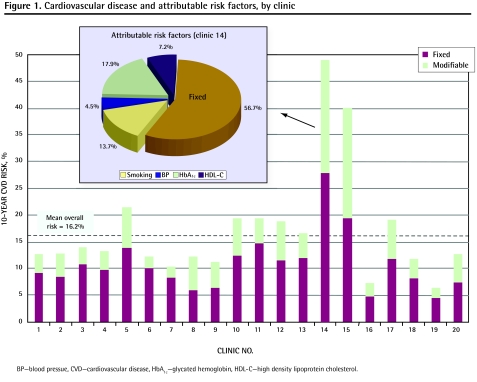

The mean age of the final sample (N = 313) was 58.6 (range 29 to 82) years, with most patients being female and Hispanic; this cohort was quite representative of the patient population seen in this region (Table 15). In addition, an attrition analysis revealed no significant differences in demographics (including age), number of medications, comorbidities, or use of health care services between the final sample and excluded patients. Individuals in this study were also quite ill, averaging nearly 5 chronic illnesses in addition to their diabetes. Fewer than half of patients had achieved recommended ADA levels for HbA1c, blood pressure, or HDL-C, and only 15.4% of patients had good control of all 3 factors. In addition, only about half of these individuals reported good self-management of diet (47.7%), regular exercise (49.8%), or consistent medication adherence (59.1%). The mean 10-year baseline absolute risk for any CVD event was 16.2%, with a greater than 7-fold range across the 20 clinics (6.5% to 48.5%). Of this absolute risk, 5.0% was due to modifiable factors, meaning an attributable risk of 30.9% (5.0/16.2). The level of risk attributable to mutable factors also varied greatly from a low of 18.3% in clinic 6 to a high of 52.4% in clinic 15. Sensitivity analyses revealed that the primary driver of modifiable risk reduction was HbA1c levels, accounting for nearly two-thirds of the decrease in attributable risk, followed by lipid levels and smoking status.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population (N = 313): A) Proportion of patients with identified characteristics; and B) mean (SD) age, number of chronic diseases, and 10-year CVD risk.

| CHARACTERISTIC | PROPORTION |

| A) | |

| Female | 54.6 |

| Hispanic | 55.2 |

| High school graduate or higher | 70.8 |

| Married | 70.2 |

| CVD risk factors | |

| • HbA1c ≥ 7.0% | 43.3 |

| • BP ≥ 130/80 mm Hg | 48.5 |

| • HDL-C ≥ 1.17 mmol/L | 50.0 |

| No. of risk factors meeting ADA guidelines | |

| • None | 17.3 |

| • 1 | 36.2 |

| • 2 | 31.2 |

| • 3 | 15.4 |

| Good self-management of diet | 47.7 |

| Regular self-reported exercise | 49.8 |

| Appropriate self-reported medication adherence | 59.1 |

| CHARACTERISTIC | MEAN (SD) |

| B) | |

| Age, y | 58.6 (11.8) |

| No. of chronic diseases | 4.9 (2.3) |

| 10-year CVD risk,* % | |

| • Absolute (total) risk | 16.2 (16.6) |

| • Attributable risk | 5.0 (7.4) |

ADA—American Diabetes Association, BP—blood pressure, CVD—cardiovascular disease, HbA1c—glycated hemoglobin, HDL-C—high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, SD—standard deviation, UKPDS—United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study.

As per the UKPDS cardiovascular risk engine.5

Figure 1 presents the variation in 10-year CVD risk, which was separately attributable to fixed and modifiable risk factors, among the 20 primary care clinics. The embedded pie chart details the proportion of attributable risk associated with each of the 4 behavioural factors for 1 selected clinic. As presented, a substantial amount of variability existed among the clinics in terms of both overall CVD risk and attributable risk. The multivariable analysis examining individual patient behaviour revealed that patients who reported good management of their diets and adherence to prescribed medication regimens improved their mean risk of any cardiovascular event by 44% and 39%, respectively (P < .03). Self-report of regular exercise had no significant effect on overall CVD risk in this study.

Figure 1.

Cardiovascular disease and attributable risk factors, by clinic

BP—blood pressue, CVD—cardiovascular disease, HbA1c—glycated hemoglobin, HDL-C—high density lipoprotein cholesterol.

DISCUSSION

The overall level of current CVD risk for patients with diabetes was dangerously elevated in our sample, with a substantial level of variation observed across the primary care clinics studied. However, it appears that targeting modifiable risk factors can dramatically reduce this risk, as nearly one-third of baseline risk can possibly be addressed through attention to mutable factors or behavioural changes. This includes both clinical measures (eg, HbA1c levels or blood pressure) and daily patient behaviour, such as diet modification or treatment adherence. Placing our findings in the context of previous studies, total CVD risk using a variety of algorithms has been found to be 21% to 31% in community settings; attributable risks looking at a finite number of factors ranged from 19% to 38%.16,17 Tanuseputro et al placed the absolute risk of CVD in Canadian patients with T2DM at 23%; no attributable risk was determined, but the prevalence of risk factors (eg, smoking status, HbA1c levels, etc) fell within the range of our study.18 Findings were mixed regarding the contribution of specific risk factors, as HbA1c levels have a greater effect on microvascular events while blood pressure has a greater influence on macrovascular events.19 Others have documented that behavioural factors are more important20; however, although diet management can effectively target weight reduction and metabolic concerns, such efforts might do little to change attributable CVD risk.21 It should be noted though that reducing attributable risk through any means yields quality-of-life benefits other than just CVD risk reduction.22

At the community level, this risk reduction in CVD would translate to a substantial number of preventable CVD events or other serious complications. These measurable clinical outcomes are accompanied by important gains in overall quality of life, along with tremendous savings in treatment costs. Jiang and colleagues estimated that improved primary care could save nearly $2.5 billion annually by reducing preventable hospitalizations arising from diabetes complications.23 Despite the high absolute CVD risk, the substantial proportion observed here to be modifiable is a sanguine finding, as interventions to enhance care coordination and patient behaviour have been demonstrated to yield dramatic benefits in improving quality of care and outcomes. For example, the chronic care model suggests that certain clinic structures and care processes (eg, organizational support, community care linkages) can assist providers and patients in better managing chronic illnesses, which should improve clinical outcomes.24 Previous studies have determined that the presence of chronic care model characteristics is associated with better quality of care and substantial reductions in attributable CVD risk.25,26

The findings of our study are limited by the fact that the cohort was recruited from regional community clinics in the United States caring for a high prevalence of Hispanic patients. Yet the clinical issues raised here and interventions targeting substantial risk factors are generalizable to many treatment settings and patient populations. Notwithstanding the post-hoc examination of missing data, we also acknowledge the possibility of some selection bias resulting from the exclusion of 25% of the original cohort. Finally, although we used a powerful theoretical framework and frequently cited self-management variables, the analyses did rely upon patient survey information and self-reported behaviour to estimate CVD risk.

Specialized efforts to recognize populations at high risk of suboptimal diabetes management are needed to tailor primary care interventions and to direct limited clinical resources. In addition to patient-level behavioural factors that influence the development of CVD events, provider and system factors play important roles in reducing the tremendous burden experienced across health care organizations. For example, given a 20% prevalence rate of diabetes within the US Department of Veterans Affairs system, the risk reduction observed in this study would translate into approximately 25 000 avoidable CVD events and 10 000 avoidable deaths among veterans every year (as per separate author analysis). The individual and cumulative benefits of minimizing preventable diabetes complications should not be underestimated.

Conclusion

High-quality diabetes care requires first identifying patients at high risk of cardiovascular complications, then targeting modifiable factors substantially associated with CVD risk. Although risk engines such as that of the UKPDS have been validated as excellent tools to help providers identify patients at higher risk of CVD,27 they are perhaps poor at precisely quantifying the total or attributable risk.28 This highlights the element of clinical judgment so essential to appropriately evaluating and treating complex diabetes patients, including the recognition of numerous factors associated with diabetes and CVD risk, both physiologic and behavioural. Lifestyle changes, including the increasingly important topic of weight reduction (or diet modification, as examined in this study), are certainly not simple to implement or maintain. However, educational interventions targeting mutable behavioural changes can be successful, dramatically improving the health status of chronically ill patients.29 While addressing attributable risk factors is clearly justified from a broader epidemiological perspective, sustained efforts at the individual practice or provider level are equally important. Specific interventions offered through primary care practice, such as smoking cessation, weight reduction, improving medications adherence, and other behavioural change strategies are quite likely to mitigate the risk of serious comorbid complications of diabetes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Grant No. K08 HS013008-02). This paper was initially presented as an abstract at a Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development meeting in February 2008 in Baltimore, Md.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a serious preventable complication of diabetes that leads to substantial disease burden, increased health services use, and premature mortality. Important modifiable CVD risk factors in patients with diabetes include glycated hemoglobin levels, blood pressure, lipid levels, and smoking status. Managing the numerous risk factors responsible for CVD in people with type 2 diabetes represents an ongoing challenge for primary care clinicians, strongly influencing their treatment approaches for this complex disease.

This study examined the common clinical and behavioural factors that contribute to CVD risk (ie, attributable risk). Results showed that the overall level of current CVD risk for patients with diabetes was dangerously elevated, with a substantial level of variation observed among the clinics studied.

Attention to modifiable risk factors can greatly reduce overall CVD risk. Specific interventions offered through primary care practices, such as smoking prevention, weight-reduction efforts, improving decisions surrounding medication adherence, and other behavioural changes, are quite likely to mitigate the risk of serious comorbid complications of diabetes.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Les maladies cardiovasculaires (MCV) sont une complication grave du diabète qu’il est possible de prévenir, et qui causent un fardeau substantiel de maladie, un plus grand recours aux services de santé et une mortalité prématurée. Parmi les importants facteurs de risque de MCV modifiables chez les patients diabétiques, on peut mentionner les taux d’hémoglobine glycolisée, la tension artérielle, les taux de lipides et le tabagisme. La prise en charge des nombreux facteurs de risque responsables des MCV chez les personnes ayant un diabète de type 2 représente incessamment tout un défi aux cliniciens de soins primaires, ce qui influence fortement leurs approches thérapeutiques à l’endroit de cette maladie complexe.

Cette étude examinait les facteurs cliniques et comportementaux courants qui contribuent au risque de MCV (c.-à-d. le risque attribuable). Les résultats ont démontré que le degré global de risque actuel de MCV chez les patients atteints de diabète était dangereusement élevé, et l’on a observé un fort niveau de variation entre les cliniques étudiées.

Si l’on porte attention aux facteurs de risque modifiables, on peut réduire de beaucoup le risque global de MCV. Des interventions spécifiques offertes par l’intermédiaire des pratiques de soins primaires, comme la prévention du tabagisme, les efforts pour réduire le poids, de meilleures décisions quant à la conformité à la médication et d’autres changements comportementaux, sont fortement susceptibles d’atténuer le risque de graves complications comorbides du diabète.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

Drs Zeber and Parchman contributed to the concept and design of the study; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Gu K, Cowie CC, Harris MI. Diabetes and decline in heart disease mortality in US adults. JAMA. 1999;281(14):1291–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.14.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wyatt SB, Winters KP, Dubbert PM. Overweight and obesity: prevalence, consequences, and causes of a growing public health problem. Am J Med Sci. 2006;331(4):166–74. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200604000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vijan S, Hayward RA. Pharmacologic lipid-lowering therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus: background paper for the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(8):650–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-8-200404200-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buse JB, Ginsberg HN, Bakris GL, Clark NG, Costa F, Eckel R, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases in people with diabetes mellitus: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(1):162–72. doi: 10.2337/dc07-9917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens RJ, Kothari V, Adler AI, Stratton IM. The UKPDS risk engine: a model for the risk of coronary heart disease in type II diabetes (UKPDS 56) Clin Sci (Lond) 2001;101(6):671–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoerger TJ, Segel JE, Gregg EW, Saaddine JB. Is glycemic control improving in U.S. adults? Diabetes Care. 2008;31(1):81–6. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1572. Epub 2007 Oct 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saaddine JB, Cadwell B, Gregg EW, Engelgau MM, Vinicor F, Imperatore G, et al. Improvements in diabetes processes of care and intermediate outcomes: United States, 1988–2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(7):465–74. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-7-200604040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaton SJ, Nag SS, Gunter MJ, Gleeson JM, Sajjan SS, Alexander CM. Adequacy of glycemic, lipid, and blood pressure management for patients with diabetes in a managed care setting. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(3):694–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.3.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerr EA, Gerzoff RB, Krein SL, Selby JV, Piette JD, Curb JD, et al. Diabetes care quality in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System and commercial managed care: the TRIAD study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(4):272–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-4-200408170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parchman ML, Romero RL, Pugh JA. Encounters by patients with type 2 diabetes—complex and demanding: an observational study. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(1):40–5. doi: 10.1370/afm.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clifford RM, Davis WA, Batty KT, Davis TM. Effect of a pharmaceutical care program on vascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes: the Fremantle Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(4):771–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes—2006. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(Suppl 1):S4–42. Erratum in: Diabetes Care 2006;29(5):1192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vallis M, Ruggiero L, Greene G, Jones H, Zinman B, Rossi S, et al. Stages of change for healthy eating in diabetes: relation to demographic, eating-related, health care utilization, and psychosocial factors. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(5):1468–74. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasila K, Poskiparta M, Karhila P, Kettunen T. Patients’ readiness for dietary change at the beginning of counselling: a transtheoretical model-based assessment. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2003;16(3):159–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-277x.2003.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parchman ML, Pugh JA, Wang CP, Romero RL. Glucose control, self-care behaviors, and the presence of the chronic care model in primary care clinics. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(11):2849–54. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2516. Epub 2007 Aug 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JD, Morrissey JR, Patel V. Recalculation of cardiovascular risk score as a surrogate marker of change in clinical care of diabetes patients: the Alphabet POEM project (Practice Of Evidence-based Medicine) Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20(5):765–72. doi: 10.1185/030079904125003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Sargeant LA, Prevost AT, Williams KM, Barling RS, Butler R, et al. How much might cardiovascular disease risk be reduced by intensive therapy in people with screen-detected diabetes? Diabet Med. 2008;25(12):1433–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanuseputro P, Manuel DG, Leung M, Nguyen K, Johansen H, Canadian Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Team Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2003;19(11):1249–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yki-Jarvinen H. Management of type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular risk: lessons from intervention trials. Drugs. 2000;60(5):975–83. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200060050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hobbs FD. Type-2 diabetes mellitus related cardiovascular risk: new options for interventions to reduce risk and treatment goals. Atheroscler Suppl. 2006;7(4):29–32. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosissup.2006.05.005. Epub 2006 Jul 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manley SE, Stratton IM, Cull CA, Frighi V, Eeley EA, Matthews DR, et al. Effects of three months’ diet after diagnosis of type 2 diabetes on plasma lipids and lipoproteins. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Diabet Med. 2000;17(7):518–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ceriello A, Sechi LA. Management of cardiovascular risk in diabetic patients: evolution or revolution? Diabetes Nutr Metab. 2002;15(2):121–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang HJ, Stryer D, Friedman B, Andrews R. Multiple hospitalizations for patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(5):1421–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parchman ML, Zeber JE, Romero RR, Pugh JA. Risk of coronary artery disease in type 2 diabetes and the delivery of care consistent with the chronic care model in primary care settings: a STARNet study. Med Care. 2007;45(12):1129–34. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318148431e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaissi AA, Parchman M. Assessing chronic illness care for diabetes in primary care clinics. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32(6):318–23. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adler AI. UKPDS-modelling of cardiovascular risk assessment and lifetime simulation of outcomes. Diabet Med. 2008;25(Suppl 2):41–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guzder RN, Gatling W, Mullee MA, Mehta RL, Byrne CD. Prognostic value of the Framingham cardiovascular risk equation and the UKPDS risk engine for coronary heart disease in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: results from a United Kingdom study. Diabet Med. 2005;22(5):554–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whittemore R. Behavioral interventions for diabetes self-management. Nurs Clin North Am. 2006;41(4):641–54. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]