In 1954, under the authorization of Sidney Herbert, the Secretary of War, Florence Nightingale brought a team of 38 volunteer nurses to care for the British soldiers fighting in the Crimean War, which was intended to limit Russian expansion into Europe. Nightingale and her nurses arrived at the military hospital in Scutari and found soldiers wounded and dying amid horrifying sanitary conditions. Ten times more soldiers were dying of diseases such as typhus, typhoid, cholera, and dysentery than from battle wounds.

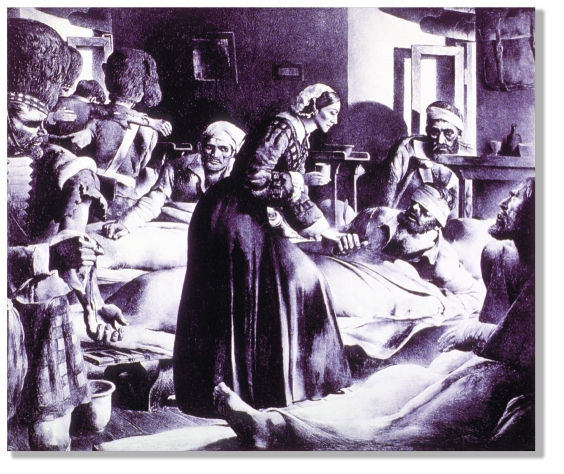

Florence Nightingale at the hospital in Scutari, by Robert Riggs. Courtesy of the Prints and Photographs Collection, History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

The soldiers were poorly cared for, medicines and other essentials were in short supply, hygiene was neglected, and infections were rampant. Nightingale found there was no clean linen; the clothes of the soldiers were swarming with bugs, lice, and fleas; the floors, walls, and ceilings were filthy; and rats were hiding under the beds.1 There were no towels, basins, or soap, and only 14 baths for approximately 2000 soldiers. The death count was the highest of all hospitals in the region. One of Nightingale's first purchases was of 200 Turkish towels; she later provided an enormous supply of clean shirts, plenty of soap, and such necessities as plates, knives, and forks, cups and glasses. Nightingale believed the main problems were diet, dirt, and drains—she brought food from England, cleaned up the kitchens, and set her nurses to cleaning up the hospital wards. A Sanitary Commission, sent by the British government, arrived to flush out the sewers and improve ventilation.

Nightingale's accomplishments during the disastrous years the British army experienced in the Crimea were largely the result of her concern with sanitation and its relation to mortality, as well as her ability to lead, to organize, and to get things done.2 She fought with those military officers that she considered incompetent; they, in turn, considered her unfeminine and a nuisance. She worked endlessly to care for the soldiers themselves, making her rounds during the night after the medical officers had retired. She thus gained the name of “the Lady with the Lamp,” and the London Times referred to her as a “ministering angel.”5 Her popularity and reputation in Britain grew enormously and even the Queen was impressed.

Nightingale's work brought the field of public health to national attention. She was one of the first in Europe to grasp the principles of the new science of statistics and to apply them to military—and later civilian—hospitals.3,4 In 1907, she was the first woman to be awarded the Order of Merit. Nightingale's image has often been sentimentalized as the epitome of femininity, but she is especially remarkable for her intelligence, determination, and amazing capacity for work.

References

- 1.Nightingale F. Florence Nightingale: Measuring Hospital Care Outcomes: Excerpts From the Books Notes on Matters Affecting the Health, Efficiency, and Hospital Administration of the British Army Founded Chiefly on the Experience of the Late War, and Notes on Hospitals. Oakbrook Terrace, Ill: Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations; 1999:41–45 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stark M. “Introduction.” Cassandra. New York: The Feminist Press; 1979:1 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kopf EW. Florence Nightingale as statistician. Res Nurs Health. 1978;1(3):93–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keith JM. Florence Nightingale: statistician and consultant epidemiologist. Int Nurs Rev. 1988;35(5):147–150 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook ET. The Life of Florence Nightingale. London, UK: Macmillen and Co., 1913 [Google Scholar]