Abstract

Objectives. We assessed the geographical distribution of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in postconflict Nimba County, Liberia, nearly 2 decades after the end of primary conflict in the area, and we related this pattern to the history of conflict.

Methods. We administered individual surveys to a population-based sample of 1376 adults aged 19 years or older. In addition, we conducted a historical analysis of conflict in Nimba County, Liberia, where the civil war started in 1989.

Results. The prevalence of PTSD in Nimba County was high at 48.3% (95% confidence interval = 45.7, 50.9; n = 664). The geographical patterns of traumatic event experiences and of PTSD were consistent with the best available information about the path of the intranational conflict that Nimba County experienced in 1989–1990.

Conclusions. The demonstration of a “path of PTSD” coincident with the decades-old path of violence dramatically underscores the direct link between population burden of psychopathology and the experience of violent conflict. Persistent postconflict disruptions of social and physical context may explain some of the observed patterns.

There is ample evidence that there is a substantial burden of psychopathology among those engaged in war—on combatants and civilians alike.1,2 Several large studies conducted in low-income countries show that the prevalence of psychopathology overall and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in particular is substantially higher in countries and among populations that have experienced conflict or mass traumatic events.3–6 Most recently, a study conducted in Liberia showed that 44% of the population had symptoms consistent with PTSD.7

Studies in postconflict areas have shown that specific subgroups are at greater risk of PTSD than others, including, for example, women8 and those who experience severe traumatic event exposure.9 It has been suggested, however, that wholesale disruption to individual daily experiences and social context rather than isolated changes on any individual-level risk factor for psychopathology drives population health after conflict.10 Some evidence in this regard comes from observations that a disproportionate burden of mortality after conflict comes from indirect causes, including disruption in basic services, social functioning, and the provision of adequate health care.11 A corollary of this observation suggests that areas most directly affected by conflict may have long-term disruption of these determinants of population health and show clear patterns of long-term psychopathology congruent with the history of conflict in the area. However, we are not aware of any study that has attempted to assess the geographical distribution of the long-term burden of PTSD in postconflict countries and its relation to the history of focal areas of violent conflict in a country.

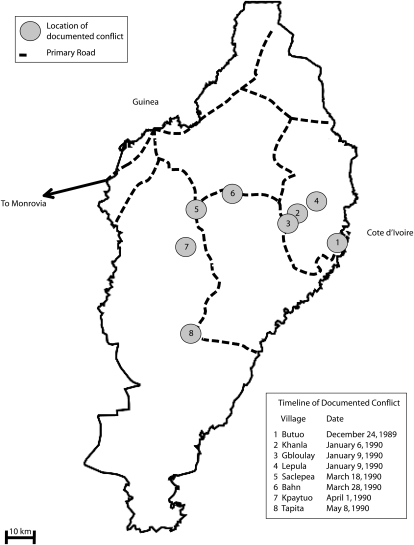

Liberia is a particularly apposite place to conduct such a study, given both its recent unfortunate history of conflict and the geographically circumscribed path of the early years of the Liberian civil conflict, particularly in Nimba County. On December 24, 1989, a little-known former civil servant in exile named Charles Taylor led a group of about 100 armed men from the Ivory Coast into the border town of Butuo in Liberia's Nimba County (Figure 1).12 Over the following days, the group, calling themselves the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL), engaged in fighting with government border officers and army personnel stationed in Butuo. There were civilian casualties, and the town's infrastructure was reported to be “pounded to rubble.”12(p16) Civilians who could do so fled over the border into the Ivory Coast.

FIGURE 1.

Documented instances of civil conflict in Nimba County, Liberia, between December 1989 and May 1990.

In the following weeks, the NPFL recruited members of Nimba's predominant Mano and Gio tribes to join their growing rebel movement, playing on historical tensions with the Krahn, the tribe of Liberian President Samuel K. Doe, in their efforts. As the size of the organization grew, so did reports of NPFL “hit-and-run attacks on small villages, singling out members of the Krahn.”13(p11) In an immediate response to these attacks, President Doe “dispatch[ed] two battalions of heavily armed troops to Nimba.”13(p11)

The stories of thousands of refugees streaming across the borders of Nimba County into Guinea and the Ivory Coast provide the most reliable information on what happened next. These refugees told of the armed forces of Liberia employing a “scorched earth” policy in their efforts to put down the rebels.14 On January 6 there was a report of Kahnla, a town less than 20 km inland from Butuo, being destroyed.15 On January 9, 2 towns neighboring Kahnla, Gbloulay and Lepula, were reportedly destroyed by fighting.16 However, the destruction of these larger towns was only the most visible product of a more widespread pattern of devastation, as reports claimed, “Government troops [made] daylight forays into outlying villages.”17 Though these forays were “ostensibly to track rebels,”17 in fact, confrontations between rebels and troops were rare.13 Rather, the army engaged in indiscriminant acts of terror, including summary executions, rape of civilians, and looting and burning of villages.13,17,18

This situation persisted over the following months, and more and more Mano and Gio individuals joined the NPFL, oftentimes in reaction to the acts of the army.18 A training camp for new recruits was established along the border with the Ivory Coast.19 Fighting continued along the primary road leading from Butuo and nearby villages. During this time many inhabitants of the northern part of Nimba County escaped direct conflict by becoming refugees. Though small outbreaks of violence did occur in the north, they were mostly limited to direct confrontations between rebels and the army.13

On March 18, 1990, there were reports of fighting in Saclepea, a major town on the road from Butuo.18 The nearby town of Bahn was “flattened and burned,” 20 with dozens killed,19,20 and on April 1, 1990, just south in Kpaytuo, 60 civilians were killed by “marauding soldiers.”20 On May 8, 1990, fighting moved south and reached Tapita.21 Finally, after months of devastation in Nimba County, the NPFL advanced toward Monrovia, moving the conflict with it. Although lasting peace did not come to Liberia as a whole until 2003, Nimba County was largely spared major military confrontations after 1990.

Our study sought to document long-term rates of PTSD in this region with a relatively brief but intense conflict 20 years previously; in addition, we explored the similarity between the geographical variability in prevalence of PTSD and the spatial patterns of conflict in Nimba County, Liberia.

METHODS

We searched published historical materials, particularly Liberian and American newspaper articles, journals, and books, to establish a timeline and focal points of conflict in Nimba County. We mapped villages that reported conflict using coordinates obtained from the Liberia Institute of Statistics and Geo-Informational Services (LISGIS). We mapped primary roads on the basis of village coordinates and information collected on-site.

Population Sampling

We obtained 2008 national census data from LISGIS to draw a 3-stage population-representative rural sample from Nimba County. In the first stage, we used populations of census enumeration areas to select 50 rural areas with probability proportional to size. We excluded enumeration areas within 7 towns with more than 2000 inhabitants. We then obtained full listings of households, identified with names of the head of household, from LISGIS for the selected enumerated areas. We randomly selected 30 households from each enumeration area. In total, 95 (6.3%) sampled households were found to be incorrectly identified on the basis of LISGIS information. In these instances, we conducted full enumeration area household listings and employed systematic random sampling methods to reselect households. In the final stage of sampling, we used a Kish table22 to randomly select a respondent from all eligible individuals in each sampled household. Eligible individuals were all those aged 18 or older who usually resided within the selected household.

Instrument and Survey Fielding

Interviewing took place during November and December 2008. Upon obtaining written informed consent, we invited all sampled individuals to respond to the standardized survey. The survey instrument included domains related to demographics, traumatic event exposure, and PTSD. We administered surveys face-to-face using personal digital assistants. We wrote the survey in English, and Liberian study personnel translated it into Liberian English.23 We conducted 4 focus groups and administered 75 pretests before interviewer deployment to refine questionnaire content and ensure translation accuracy. Twelve interviewers, deployed in 3 teams, administered the surveys. All interviewers completed a 2-week training session immediately before deployment. We conducted interviews at selected households in a private location; interviews took approximately 1 hour to complete. To ensure the quality of data collected, we observed 5% of interviews and reinterviewed another 3% of respondents at random. We collected travel times from sampled villages to the nearest health facility, primary school, and goods market during interviews with village chiefs.

Traumatic Events and Symptoms of PTSD

We used the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire to assess both experiences of traumatic events and current symptoms of PTSD. The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire includes items consistent with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition24 and has been used widely in developing country settings.25,26 Respondents were deemed to have symptoms consistent with PTSD according to instrument standards and precedent in the literature.5,27

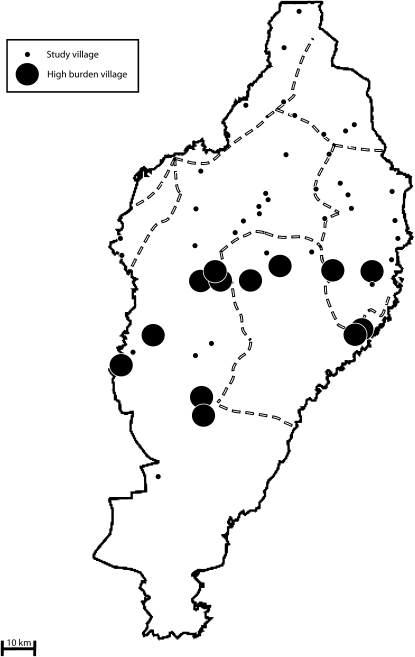

Mapping the Burden of PTSD

We divided the sample into quartiles and identified those villages in the quartile with the highest proportions of trauma or PTSD as “high burden” villages. We analyzed war-related traumatic events, and we present data about having had a friend or family member murdered as an illustrative measure of relevant traumatic event exposure. We then mapped the high burden villages as large circles on separate maps; small circles represented all other villages. We conducted sensitivity analyses limiting data to respondents who were aged at least 10 years during the conflict. We conducted all mapping using ArcGIS software.28

Statistical Analysis

We calculated a correlation matrix to estimate crude associations between (1) village distance from the nearest site of documented conflict, (2) mean number of traumatic events in a village, and (3) the proportion of respondents within a village with symptoms consistent with PTSD. In addition, we fit an ecologic linear regression model to village-level data to estimate the association between the distance from the nearest site of documented conflict and the travel time to important social institutions, including a health facility, a primary school, and a goods market. We carried out all statistical analyses with Stata version 10.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Of the 1464 eligible persons we approached to participate in the study, we were unable to locate 27 after 3 attempts, and 3 refused to participate. A total of 1434 (98.0%) persons completed the questionnaire. We restricted analysis to those individuals aged 19 years or older because they were born before the initial incursion in December 1989. The final analysis included 1376 individuals. Fifty-four percent of survey respondents were male (Table 1), 58.3% were aged 35 or older, and 56.6% had received some schooling. The mean number of traumatic events reported was 17.5 (SE = 0.3). War-related traumatic events ranged from 3.5% for rape to 97.4% for forced leaving under dangerous conditions. Overall, 49.7% had experienced the murder of a family member or friend. The overall prevalence of PTSD was 48.3% (95% confidence interval = 45.7, 50.9; n = 664), ranging from 7% in 3 villages to 100% in 1 village.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of a Population-Representative Sample of Residents Aged 19 Years and Older (n = 1376): Nimba County, Liberia, 2008

| Characteristic | No. (%) or Mean (SE) |

| Individual level | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 745 (54.1) |

| Female | 631 (45.9) |

| Age, y | |

| < 35 | 574 (41.7) |

| ≥ 35 | 802 (58.3) |

| Education | |

| No schooling | 597 (43.4) |

| Some schooling | 779 (56.6) |

| Traumatic events | |

| Number of traumatic events | 17.5 (0.3) |

| Experienced murder of family member or friend | 684 (49.7) |

| Symptoms consistent with PTSD per HTQ | 664 (48.3) |

| Village level | |

| Travel time to a health facility, mean h | 2.2 (0.3) |

| Travel time to a primary school, mean h | 0.5 (0.1) |

| Travel time to a goods market, mean h | 3.2 (0.4) |

| Distance from nearest location of document conflict, mean km | 21.6 (2.3) |

Notes. HTQ = Harvard Trauma Questionnaire; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Villages with a high versus low proportion of family members or friends murdered and of PTSD are presented in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. The preponderance of villages with the highest percentages of sampled inhabitants that experienced a family member or friend murdered were along the primary road leading from Butuo into Nimba County. We obtained similar results (not shown) when assessing other war-related traumatic events. As shown in Figure 3, villages with the highest prevalence of PTSD had a similar geographical distribution. Results from correlation calculations (Table 2) confirmed that villages located nearer to documented conflict had significantly increased traumatic events (P = .018) and PTSD prevalence (P = .002). Furthermore, villages with more reported traumatic events had significantly increased PTSD (P < .001) compared with that of villages with fewer reported traumatic events. Results from a linear regression model showed that village distance from documented conflict was not significantly associated with travel time to a health facility, a primary school, or a goods market (data available upon request from authors). Patterns of PTSD were comparable when the data were limited to respondents who were aged 10 years or older during the conflict.

FIGURE 2.

Geographical distribution of experience of a murdered family member or friend in sampled villages: Nimba County, Liberia, 2008.

FIGURE 3.

Geographical distribution of symptoms consistent with posttraumatic stress disorder in sampled villages: Nimba County, Liberia, 2008.

TABLE 2.

Correlations Between Village-Level Measures of Distance From Documented Conflict, Traumatic Events, and PTSD for Sampled Villages (n = 50): Nimba County, Liberia, 2008

| Distance From Documented Conflict, Correlation (P value) | Traumatic Events, Correlation (P value) | PTSD, Correlation (P value) | |

| Distance from documented conflict | 1.00 (…) | ||

| Traumatic events | −0.33 (.018) | 1.00 (…) | |

| PTSD | −0.44 (.002) | 0.59 (< .001) | 1.00 (…) |

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

DISCUSSION

Using data from a population-based representative survey in Nimba County, Liberia, combined with a historical analysis, we showed both that the prevalence of PTSD in Nimba County remains high nearly 2 decades after the end of the principal conflict and that the geographical patterns of traumatic event experiences and of PTSD are consistent with the best available information about the path of the violent civil conflict that Nimba County experienced from 1989 to 1990.

Our demonstration of a high prevalence of PTSD in Nimba County is not surprising and is consistent with a recent nationally representative survey in Liberia showing that 44% of respondents in the general population reported symptoms consistent with PTSD.7 It is plausible that our slightly higher prevalence of PTSD is consistent with the greater burden of war experienced in Nimba County as compared with some other parts of the country.29 Reports of PTSD in other postconflict low-income countries have documented a comparably high prevalence of PTSD.5,9

Of note is the observation of a high prevalence of PTSD in these populations long after the conflict had stopped, in this case nearly 18 years after the principal conflict in Nimba County had ended and 5 years after war in Liberia ended entirely. Although research on the persistence of PTSD long after conflict is limited, this appears consistent with other recent studies showing a high prevalence of PTSD decades after conflict is over.26 To put this in perspective, the lifetime prevalence of PTSD in the United States as documented in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication is 6.8%,30 and US-based studies suggest that more than one third of all PTSD after traumatic experiences resolves in the first 6 months after such events.31 The prolonged high prevalence of PTSD documented here is consistent with the unimaginably high levels of violence and trauma (i.e., nearly half of respondents report having had a friend or family member murdered) experienced by the population of Nimba County.

The persistently high prevalence of PTSD throughout the county may in part be explained by widespread material deprivation wrought by the war.32 For example, the county's electrical grid, roads, and railways were almost entirely destroyed during the conflict, leaving most villages with few links to schools and markets and, as a result, limited economic opportunities.33 Rebuilding has begun only in the past several years. Even today, there is no electrical grid, and only a few commercial buildings have generators in the town of Ganta, the commercial capital of Nimba. Local nongovernmental organizations report high rates of unemployment throughout the county. The links between economic vulnerability and loss of employment and PTSD have been documented in other settings.34,35

Of particular interest here is the remarkable concordance, demonstrated in Figures 2 and 3 and confirmed with correlation calculations, between the history of conflict and the reports of traumatic events and burden of PTSD in sampled villages. This suggests that there is much more to the aftermath of conflict than a “path of blood” and that populations who are unfortunate enough to have been in the path of severe, violent conflict are likely to bear a burden of psychopathology for decades thereafter. We note that the demonstrable congruence in the pattern of conflict and psychopathology is even more remarkable when considering that it holds even though many in the sample were very young during the period of active conflict and did not themselves experience some of the key traumatic events that are also geographically congruent with the history of conflict. This suggests that the pattern observed here is driven by more than the personal experience of conflict by respondents and may be mediated by community-level and familial social and psychological factors as well as material deprivation.32 However, the pattern of conflict in Nimba does not appear to have differentially undermined the county's formal social institutions. Villages near to and far from documented conflict had similar physical access to health care, education, and economic markets. Future research efforts may be helpful in delineating the influence of informal support systems, such as personal relationships and community ties,36 and formal social institutions on long-term psychopathology in the wake of civil war.

Although we are not aware of comparable postconflict analyses, evidence of geographical patterning of PTSD has been found after mass traumatic events, such as disasters. For example, after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in New York City it was shown that the prevalence of PTSD decreased monotonically in the population with distance from the World Trade Center.37 We believe that the conflict mapping method employed here may be relevant to a broad range of academic disciplines, including political science,38 anthropology,39 and geography.40

Our study did have limitations. Although we used a well-established, widely used measure of PTSD, results from structured interviews always need to be interpreted with caution absent clinical verification. We also could not be certain that the persons interviewed were those who experienced the conflict more than a decade earlier. However, this is a very stable population, deeply rooted to historical place, and by all accounts persons live nearly exclusively in their ancestral villages and returned to these same villages even after displacement. Furthermore, we have presented PTSD symptoms from all causes; however, the overwhelmingly high prevalence of PTSD and reports of war-related traumatic events strongly suggest an explicit link between war-related events and psychopathology. A paucity of official records about the civil war in Liberia limited our historical analysis; however, the consistency of the reports of conflict across the extant sources provides confidence about these findings.

We show here that there is a persistent high prevalence of PTSD nearly 2 decades after the end of active conflict in Nimba County, Liberia, and that areas with a historical record of conflict are clearly also the areas with a persistently high prevalence of PTSD. This suggests both that interventions in the postconflict era could fruitfully target areas with a history of conflict and that interventions aimed at rebuilding social and physical infrastructure in these areas may be an inextricable part of mental health treatment in these countries.

Acknowledgments

This article was produced with the support of the Departments of Health Management and Policy and Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health.

Human Participant Protection

The institutional review boards at the University of Michigan and the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare of Liberia provided human participants research approval for the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all respondents.

References

- 1.Levy BS, Sidel VW. Health effects of combat: a life-course perspective. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:123–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mollica RF, Cardozo BL, Osofsky HJ, et al. Mental health in complex emergencies. Lancet. 2004;364(9450):2058–2067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Jong JT, Komproe IH, Van Ommeren M. Common mental disorders in postconflict settings. Lancet. 2003;361(9375):2128–2130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scholte WF, Olff M, Ventevogel P, et al. Mental health symptoms following war and repression in eastern Afghanistan. JAMA. 2004;292(5):585–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts B, Ocaka KF, Browne J, et al. Factors associated with post-traumatic stress disorder and depression amongst internally displaced persons in northern Uganda. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):168–176 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson K, Asher J, Rosborough S, et al. Association of combatant status and sexual violence with health and mental health outcomes in postconflict Liberia. JAMA. 2008;300(6):676–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klaric M, Klaric B, Stevanovic A, et al. Psychological consequences of war trauma and postwar social stressors in women in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Croat Med J. 2007;48(2):167–176 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Jong JT, Komproe IH, Van Ommeren M, et al. Lifetime events and posttraumatic stress disorder in 4 postconflict settings. JAMA. 2001;286(5):555–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galea S, Wortman K. The population health argument against war. World Psychiatry. 2006;5(1):31–32 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coghlan B, Brennan RJ, Ngoy P, et al. Mortality in the Democratic Republic of Congo: a nationwide survey. Lancet. 2006;367(9504):44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourke G. Refugees tell of mayhem after attempt to topple Doe. The Independent. January 6, 1990:16 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bourke G. Thousands flee massacres by Liberian army: President Doe's campaign against rebels in the bush has turned into genocide against a rival tribe. The Independent. January 29, 1990:11 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perlez J. Refugees report Liberian ‘scorched earth’ drive on rebels. New York Times. January 9, 1990:3 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Associated Press. Many flee Liberia as clash destroys towns, envoys say. New York Times. January 6, 1990:3 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liberia: human rights group denounces massacre. Inter Press Service. January 9, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Independent. Tribal war rages after bid to overthrow gov't fails; Liberia. Sydney Morning Herald. January 20, 1999:21 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Randal JC. Liberia seen unable to crush rebels; army rampage said to spark resistance. Washington Post. March 18, 1990:18 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Associated Press U.S. missionary and his wife are reported slain in Liberia. New York Times. March 29, 1990:9 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones T. [No title]. The Associated Press. International News. June 27, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noble KB. War of quick but brutal clashes unfolds in Liberia. New York Times. May 18, 1990:3 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kish L. A procedure for objective respondent selection within the household. J Am Stat Assoc. 1949;44(247):380–387 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomczyk B, Goldberg H, Blanton C, et al. Women's Reproductive Health in Liberia: The Lofa County Reproductive Health Survey. Washington, DC: US Agency for International Development; January–February 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mollica RF. The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire. Validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180(2):111–116 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dworkin J, Prescott M, Jamal R, et al. The long-term psychosocial impact of a surprise chemical weapons attack on civilians in Halabja, Iraqi Kurdistan. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196(10):772–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mollica RM, Massagli L, Silove M, et al. Measuring Torture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 28.ArcMap, Version 9.3 Redlands, CA: Environmental Systems Research Institute; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellis S, Mask of Anarchy: The Destruction of Liberia and the Religious Roots of an African Civil War. London: Hurst & Co Ltd; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989;44(3):513–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Transitional Government of Liberia Joint Needs Assessment Report. New York: United Nations Development Group; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nandi A, Galea S, Tracy M, et al. Job loss, unemployment, work stress, job satisfaction, and the persistence of posttraumatic stress disorder one year after the September 11 attacks. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46(10):1057–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson BD, Fernandez WG, Galea S, et al. War-related psychological sequelae among emergency department patients in the former Republic of Yugoslavia. BMC Med. 2004;2:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):458–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galea S, Boscarino J, Resnick H, et al. Mental health in New York City after the September 11 terrorist attacks: results from two population surveys. : Manderscheid RW, Mental Health, United States 2002. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2003:83 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buhaug H, Gates S. The geography of civil war. J Peace Res. 2002;39(4):417–433 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campbell D. Apartheid cartography: the political anthropology and spatial effects of international diplomacy in Bosnia. Polit Geogr. 1999;18(4):395–435 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dahlman C, Tuathail GO. The legacy of ethnic cleansing: the international community and the returns process in post-Dayton Bosnia-Herzegovina. Polit Geogr. 2005;24(5):569–599 [Google Scholar]