Abstract

Objective

To better define the activity of soluble CXCL16 to recruit polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) in vivo, we developed a novel animal model of gout pathology. We tested CXCL16 to recruit PMNs in a human normal synovial tissue (NL ST) severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mouse chimera injected intragraft with gouty SF.

Methods

For in vitro studies, we utilized the modified Boyden chemotaxis system to identify CXCL16 as an active recruitment factor for PMNs. Cell migration could be reduced by neutralizing gouty SF CXCL16 activity. For in vivo analysis, fluorescently dye-tagged PMNs were injected i.v., while a simultaneous injection of diluted gouty SF containing CXCL16 was administered intragraft. We similarly inhibited the receptor for CXCL16, CXCR6, by incubating PMNs with neutralizing CXCR6 antibodies and examined PMN recruitment to gouty tissues in the SCID mouse chimera system.

Results

CXCL16 is highly elevated in gouty SF and PMNs migrate to CXCL16 in vitro. NL ST SCID mouse chimeras injected intragraft with gouty SF depleted of CXCL16 during PMN transfer showed a significant 50% reduction of PMN recruitment to engrafted tissue compared to grafts administered sham depleted gouty SF. Similar findings were achieved when incubating PMNs with neutralizing anti-CXCR6 antibody before injection into chimeras administered gouty SF.

Conclusion

Overall, this study outlines the effectiveness of the human SCID mouse chimera system as a viable animal model for gout, identifying a primary function of CXCL16 as a significant mediator of in vivo PMN recruitment to gouty SF.

Keywords: Inflammation, chemokines, SCID, gout, CXCL16

Introduction

Gout results from synovial tissue (ST) deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate (MSUM) crystals from supersaturated extracellular fluids. Urate crystal deposition in joints causes acute inflammatory responses set off by the negatively charged crystal surfaces activating complement (e.g. C5a, C3a), and release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. IL-8/CXCL8, for example, is a chemokine and polymorphonuclear cell (PMN) recruitment factor that is in gout (1, 2). PMNs respond to CXCL8 via its corresponding receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 (3). In addition, rabbits deficient in membrane attack complex (MAC) component C6 reveled that MAC activation appears to play a major role in intraarticular CXCL8 generation and in neutrophil recruitment in an experimental acute gouty arthritis model of the rabbit knee (4).

CXCL8 inhibition has shown to be a principal recruitment factor in animal models of gout. In agreement, Nishimura et al, showed that intraarticular injection of a neutralizing anti-CXCL8 antibody significantly attenuated crystal-induced joint swelling and neutrophil infiltration in the rabbit knee (5). In sum, the overall process is thought to involve MSUM crystal deposition that induces CXCL8 secretion and subsequent recruitment of PMNs to inflamed joints. There may also exist multiple CXCR2 ligands in gouty SF that could account for chemotactic activities beyond those of CXCL8, such as growth regulated oncogene-α (Groα)/CXCL1, that have shown robust neutrophil recruitment activity in murine urate crystal induced inflammatory subcutaneous air pouch models (3). Thus, chemokines and their cellular receptors, especially CXCR2, have generated great interest as a foundation for inflammation intervention strategies.

Although therapeutics for gout are currently being improved to alter or reduce the activity of enzymes required for uric acid formation (6–14), alternative strategies targeting chemokines or other growth factors involved in PMN recruitment may show clinical potential as well. Because of the association of MSUM crystal formation, PMN recruitment and chemokine release such as CXCL8, there continues to be enormous interest in therapies that block not only CXCL8, but other chemokines that may have proinflammatory activity in gout and many other inflammatory disorders (1, 2, 15–20).

Our initial studies largely focused on exploring new avenues of cytokine expression in gout, with a principal spotlight on chemokines involved in mononuclear and/or PMN recruitment. To address this, we examined the expression of several CC and CXC chemokines in gouty SFs (16, 21). We found that chemokines expressed in gouty synovial fluid (SF) other than CXCL8 were interferon gamma inducible protein-10 (IP-10/CXCL10), monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2) and CXCL16. CXCL16 was set apart from other chemokines for further analysis due to its unusually elevated concentrations in gouty SF. To determine if CXCL16 inhibition could influence PMN migration, samples of anti-CXCL16 and sham depleted gouty SFs were tested in vitro using a Boyden chemotaxis chamber system. We also put forward a novel model for crystal induced arthritis that facilitated evaluation of CXCL16 inhibition on human PMN migration from the peripheral blood to engrafted human ST. To utilize this model, we injected gouty SF directly into human normal (NL) ST engrafted into severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice, followed by i.v. injections of fluorescently dye-tagged PMNs (17). “Humanizing” the mice in this way facilitated use of actual gouty SFs, and provided clinical relevance that allowed use of human STs to quantify PMN recruitment in an in vivo setting. The result of PMN migration to engrafted NL ST in response to injected gouty SF was evaluated and linked to gouty SF CXCL16 concentrations.

Methods

Patient samples

The studies described utilized the collection of human SFs. For this study, we obtained gouty SFs which are normally discarded from patients. Gout was confirmed by crystal detection in gouty SF. Prior to therapeutic arthrocentesis unrelated to the proposed research, patients were asked whether they were willing to contribute SF to the study. Gouty SF specimens were aliquated and stored at −80°C. All specimens were obtained with Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval.

Human ST collection

We have utilized the Cooperative Human Tissue Network (CHTN) and National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI) for cadaveric NL ST specimens. NL STs were taken from primarily from knees, and processed within 24 hours of death. STs were screened and considered normal if the donors were not previously diagnosed with a rheumatic disease such as rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis. Under sterile conditions, NL ST is isolated from surrounding tissue, cut into 0.5 cm3 segments, and screened for pathogens before implantation. All tissues were stored frozen at −80°C in a freezing media (80% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum with 20% dimethyl sulfoxide v/v), thawed and washed three times with PBS before insertion into mice. The recovery rate for tissues using this method is 100%. All specimens were obtained with IRB approval.

SCID Mice

SCID/NCr mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). All mice were maintained in a pathogen-free animal facility and given food and water ad libitum.

Enzyme Linked Immunosorbant Assay (ELISA) technique

ELISA assays were performed as described previously (20) for chemokines not available on Luminex panels (described below). Briefly, IL-1β, CXCL8 and CXCL16 levels were measured by coating 96-well polystyrene plates with anti-human chemokine antibodies (R&D Systems, Minneapolis MN) followed by a blocking step. All samples were added in triplicate with recombinant human chemokine as standard (R&D Systems). Subsequently, biotinylated anti-human antibody and streptavidin peroxidase were added, and sample concentrations were measured at 450nm after developing the reaction with tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate. The correlation coefficients for the ELISAs were approximately 0.99 with a sensitivity (usually around 15 pg/ml) well below the average concentrations of IL-1β, CXCL8 or CXCL16 in gouty SF.

Luminex

Luminex is a technique that combines flow cytometry analysis and ELISA. Luminex was performed with kits from BIOSOURCE (Camarillo, CA) and used per manufacturer’s instructions. Luminex data is very accurate. It should be noted that we not using the plateau part of the concentration curve but rather data in the middle with a linear correlation coefficient of 0.99. Similar results were found with the ELISA assays. A panel of cytokines was measured in gouty SF, including fractalkine (fkn/CX3CL1), granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), IL-17, CXCL10, CCL2, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α/CCL3), MIP-β/CCL4, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

SF neutralization studies

Diluted SF (1:300 with PBS) was pre-incubated with neutralizing polyclonal goat anti-human CXCL16 antibodies (catalog no. AF976; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at a concentration of 135ng/100μl diluted SF (from undiluted gouty SF samples containing approximately 25ng/ml CXCL16). Control sham depleted gouty SFs were incubated similarly with corresponding control non-specific antibody (goat IgG, R&D Systems) as recommended by the vendor and previously described for RA SF (20). Similarly, for human CXCL10 neutralization, goat anti-human CXCL10 antibody was used (catalog no. AF-266-NA; R&D Systems) and the control antibody was also goat IgG. Only SFs expressing average chemokine concentrations (typically around 25 ng/ml for CXCL16 and 304 pg/ml for CXCL10) were used and PMNs were assayed for in vitro chemotaxis assays and in vivo migration studies, as described below.

PMN isolation and fluorescent dye incorporation

Human PMNs were isolated from the peripheral blood (PB) (~100ml) of NL healthy adult volunteers and applied to Ficoll gradients as previously described (22). PMN viability and purity of cells was routinely >98%. For in vivo studies, PMNs were fluorescently dye-tagged with PKH26 fluorescent dye using a dye kit per manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). Successful labeling of PMNs was confirmed by performing cytospin analysis and observing fluorescing PMNs under a microscope equipped with a 550nm filter.

In vitro migration assay

Chemotaxis assays were performed using a 48-well modified Boyden chamber system, as done previously (20, 23). For studies using gouty SFs, all samples were centrifuged, diluted, and centrifuged again before use in in vitro assays. Sham and antibody blocked gouty SFs were processed similarly. Stimulant (25μl) of either CXCL16 or diluted gouty SF (1:300 in PBS) was added to the bottom wells of the chambers, while 40μl of PMNs at 1.0×106 cells/ml were placed in the wells at the top of the chamber. Sample groups were assayed in quadruplicate, with the results expressed as cells migrated per high power field (hpf; 400X). Hank’s Balanced Saline Solution (HBSS) and fMLP used at 10−7M were used as negative and positive stimuli, respectively.

Generating human NL ST SCID mouse chimeras

SCID mouse human ST chimeras represent a unique way to study human tissue in vivo. We used this model to study whether gouty SFs, some depleted of CXCL16, can recruit PMNs in vivo. Six to eight week old immunodeficient mice were anesthetized with Isoflurane under a fume hood and a 1.5 cm incision was made with a sterile scalpel on the midline of the back. Forceps were used to blunt dissect a path for insertion of the ST graft. ST grafts were implanted on the graft bed site and sutured using surgical nylon. Grafts were allowed to “take” and the sutures removed after 7–14 days. Within 4–6 weeks of graft transplantation, unpooled diluted gouty SFs (1:300 in PBS) were injected into grafts. For studies using gouty SFs, all samples were centrifuged, diluted, and centrifuged again before administration into chimeras. Sham and antibody blocked gouty SFs were processed similarly. Purified, gouty SFs, either CXCL16 depleted (specific neutralizing anti-human CXCL16, R&D Systems) or sham depleted (non-specific IgG, R&D Systems), were injected directly into ST grafts using a 23 gauge needle. For some studies, PMNs were incubated with monoclonal mouse anti-human CXCR6 receptor antibodies (125μg/ml mouse anti-human CXCR6 antibody was added to 0.5ml PMNs at 5×106 PMNs/100μl; catalog no. MAB699, R&D Systems). Control PMNs were incubated similarly with nonspecific mouse IgG before injection into chimeras. Mice were euthanized and grafts harvested 48 hours later. For all in vivo studies, PMNs integrated to the implanted ST were examined from cryosectioned slides using a fluorescence microscope and scored. All sections were analyzed and evaluators were blinded to the experimental set up.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance values for all studies were calculated using the Student’s t-test. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical data was expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Cytokine measurements in gouty SF by Luminex and ELISA

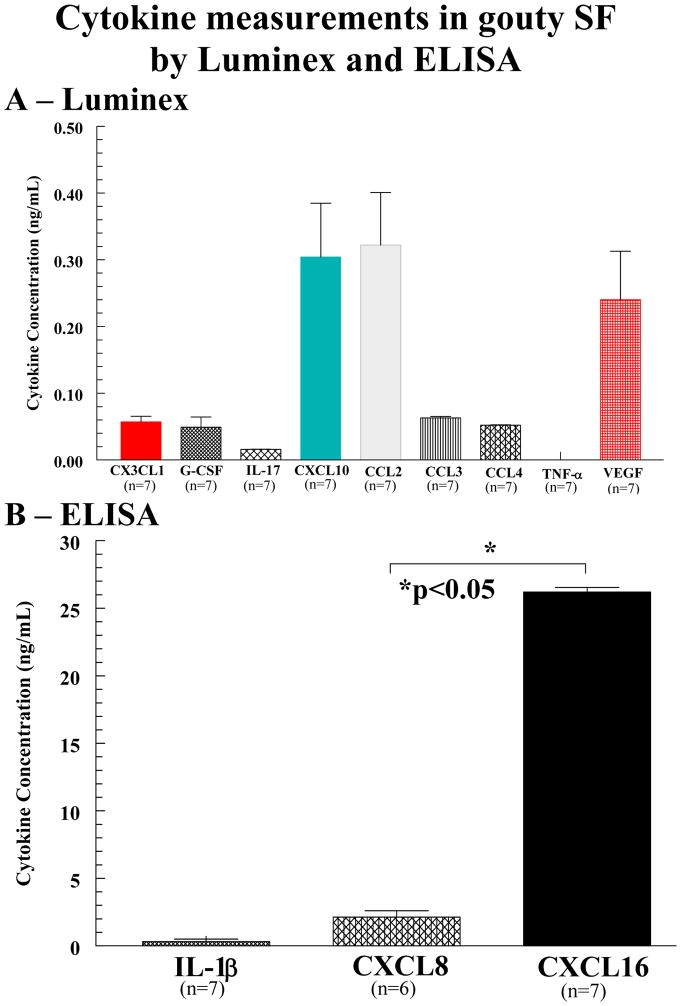

As shown, chemokines CXCL10, CCL2, and the angiogenic factor VEGF were significantly upregulated compared to other cytokines measured (figure 1A). In the lower panel (figure 1B), note that the concentration of CXCL16 and CXCL8, both measured by ELISA, are at least one hundred-fold higher for CXCL16 and 10 fold higher for CXCL8 compared to other cytokines measured. Also note the lack of TNF-α and the lymphokine IL-17 in the gouty SFs examined (all data is expressed as mean ± SEM).

Figure 1.

Cytokine measurements in gouty SF by Luminex and ELISA. A Chemokines CXCL10, CCL2, and the angiogenic factor VEGF are significantly upregulated compared to other cytokines measured. All values shown are final concentrations found in undiluted gouty SF. B Note the concentration of CXCL16 is at least one hundred-fold higher than that of other cytokines in gouty SF. CXCL8 was similarly elevated compared to many other cytokines, but was over ten-fold less abundant than CXCL16 in gouty SF (*p<0.05). Also, note the lack of TNF-α and IL-17 in gouty SF (error bars represent SEM).

CXCL16 induces PMN migration

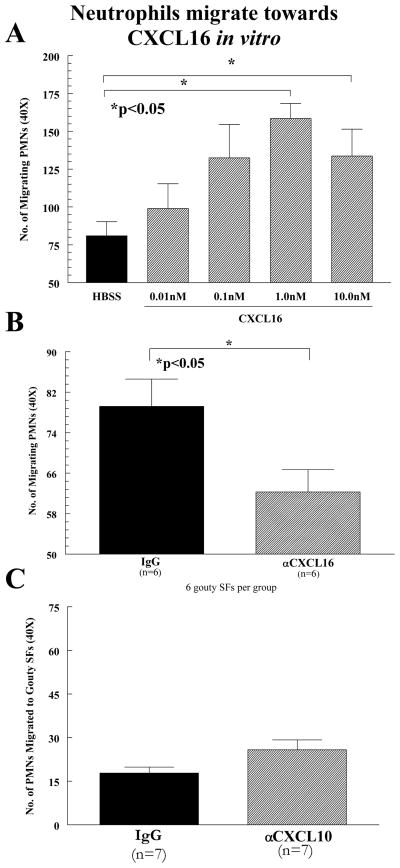

NL human peripheral blood (PB) PMNs were assayed for their chemotactic response to CXCL16 in a modified Boyden chamber to determine a proinflammatory role for CXCL16. fMLP and HBSS served as positive and negative controls, respectively. CXCL16 induces chemotaxis for human PMNs in a dose-dependent manner and is maximal between 1.0nM and 10.0nM (figure 2A; n=number of experiments, 6 gouty SFs per group). To determine the participation of CXCL16 in PMN migration in gout, gouty SFs containing average levels of CXCL16 (approximately 25ng/ml, before dilution of 1:300 in PBS) were incubated with anti-human CXCL16 antibody. SFs were then tested in an in vitro migration assay and compared to sham depleted controls. Gouty SFs showed approximately a 20% decrease (p<0.05) in PMN migratory activity after incubation with neutralizing CXCL16 antibodies (figure 2B). We also examined CXCL10 as it is also highly upregulated, akin to CXCL8 and CXCL16, compared to other cytokines analyzed in gouty SF (figure 1). As a role for the CXCL8-CXCR2 ligand receptor pair in PMN chemotaxis is already well established (24), we compared CXCL16 mediated chemotaxis to that of an alternative CXC chemokine, CXCL10, using gouty SF antibody blocking studies. Note that comparing CXCL16 mediated chemotaxis to that of CXCL10, not known to recruit PMNs but monocytes, T cells, NK cells and dendritic cells serves as a natural negative control for CXCL16 mediated PMN chemotaxis. Unlike CXCL16, we showed no effect on PMN chemotaxis in vitro upon blocking CXCL10 (figure 2C), confirming that not all CXC chemokines are effective PMN recruitment factors in gout (all data is expressed as mean ± SEM).

Figure 2.

Neutrophils migrate towards CXCL16 in vitro. A CXCL16 induces chemotaxis for human PMNs in a dose-dependent manner, and is maximal between 1.0nM and 10.0nM. B Blocking of CXCL16 from gouty SFs with neutralizing anti-CXCL16 antibodies reduced the in vitro PMN chemotactic activity of the gouty SFs (n=number of experiments). C Neutrophils fail to migrate toward CXCL10 in vitro. CXCL10 did not induce chemotaxis for human PMNs at concentrations similar found in gouty SF (n=number of experiments; error bars for all experiments represent SEM).

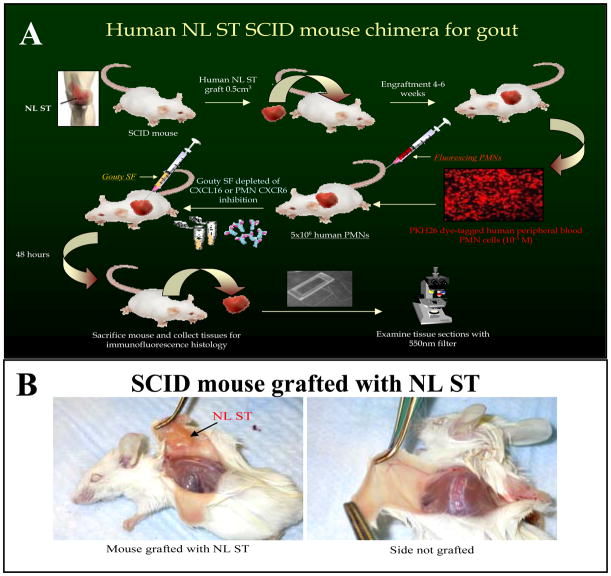

PMN recruitment to engrafted human ST in a SCID mouse chimera

To test PMN migration in vivo, we used a ST SCID mouse chimera. Figure 3A is a diagram of the procedure. After 4 to 6 weeks, animals engrafted with human NL ST showing no signs of rejection after 4–6 weeks were used (figure 3B). To determine homing of NL human PMNs, freshly isolated cells were fluorescently dye-tagged with PKH26 and 5×106 cells/100μl/mouse were injected i.v. by tail vein forty-eight hours before sacrifice. Cryosections (10μm) of the NL ST grafts were examined using a fluorescence microscope. SCID mice engrafted with NL ST receiving intragraft injections of diluted (1:300 in PBS) gouty SF showed robust recruitment of i.v. administered fluorescently dye-tagged PMNs. These results indicate that exogenously administered gouty SF containing CXCL16 as well and many other PMN chemotactic factors recruit human PMNs in the SCID mouse chimera system.

Figure 3.

A Diagram of gouty SCID mouse chimera procedure. B. SCID mouse grafted with human NL ST.

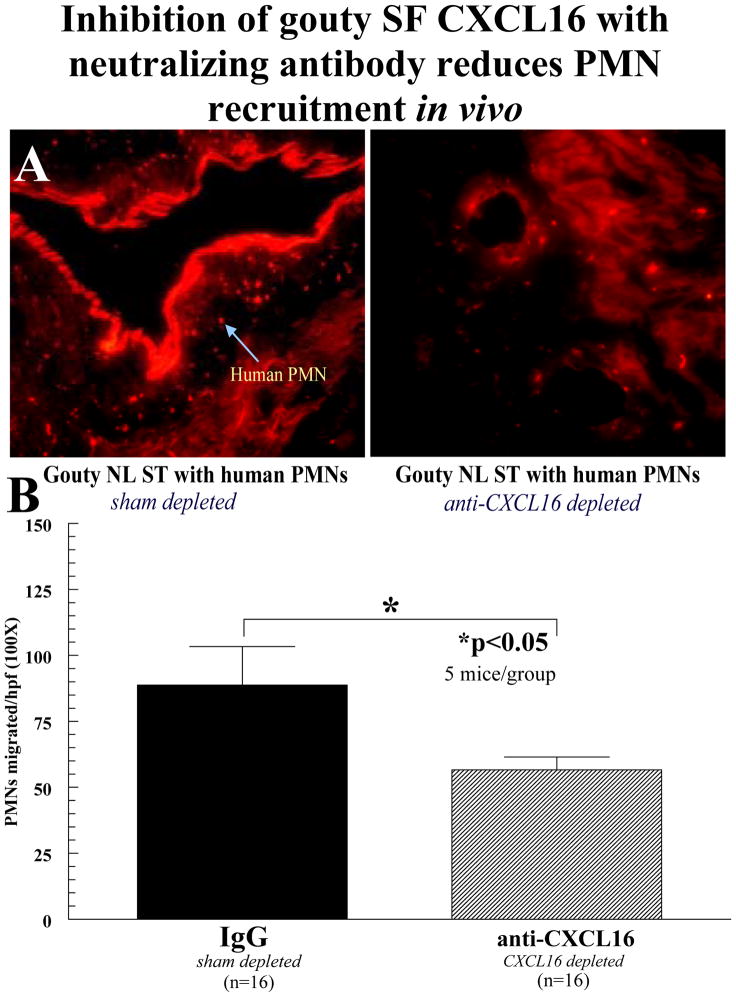

Antibody blocking of CXCL16 in gouty SF reduces recruitment of PMNs in vivo

Dye-tagged PMNs were allowed to migrate for 48 hours to human grafts injected with gouty SF (diluted 1:300 in PBS). NL ST grafts were then harvested, snap frozen, and cryosectioned. Migrated, dye-tagged cells were observed in the NL ST grafts using a fluorescence microscope (figure 4A). Human NL ST SCID mouse chimeras injected intragraft with gouty SFs containing blocking antibodies to CXCL16 at the time of PMN transfer showed a 50% reduction of PMN recruitment to the grafts compared to grafts administered sham depleted gouty SF (figure 4B). This is in agreement with our in vitro studies, and further demonstrates that CXCL16 expression correlates with PMN recruitment to gouty SF (all data is expressed as mean ± SEM).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of gouty SF CXCl16 with neutralizing antibody reduces PMN recruitment in vivo. A PKH26 red fluorescent dye-tagged human PMNs (5×106) were injected i.v. into SCID mice engrafted for 4 to 6 weeks with human NL ST. Before administering cells, ST grafts were injected with gouty SF (diluted 1:300 with PBS; 100μl/graft) either blocked with neutralizing anti-CXCL16 antibodies or sham depleted with nonspecific IgG. At 48 hours, grafts were harvested and tissue sections were examined using immunofluorescence microscopy at 550nm (400×). The upper panel shows a representative NL ST cryosection with dye-tagged human cells migrating in response to the injected diluted gouty SF. As shown, a significant reduction in PMN recruitment to gouty SF was seen towards gout depleted SFs of CXCL16. B A graph of all the data is presented. PMN migration was quantified by dividing the number of cells per hpf in each ST tissue section counted at 100× (n=number of ST sections counted; (error bars represent SEM).

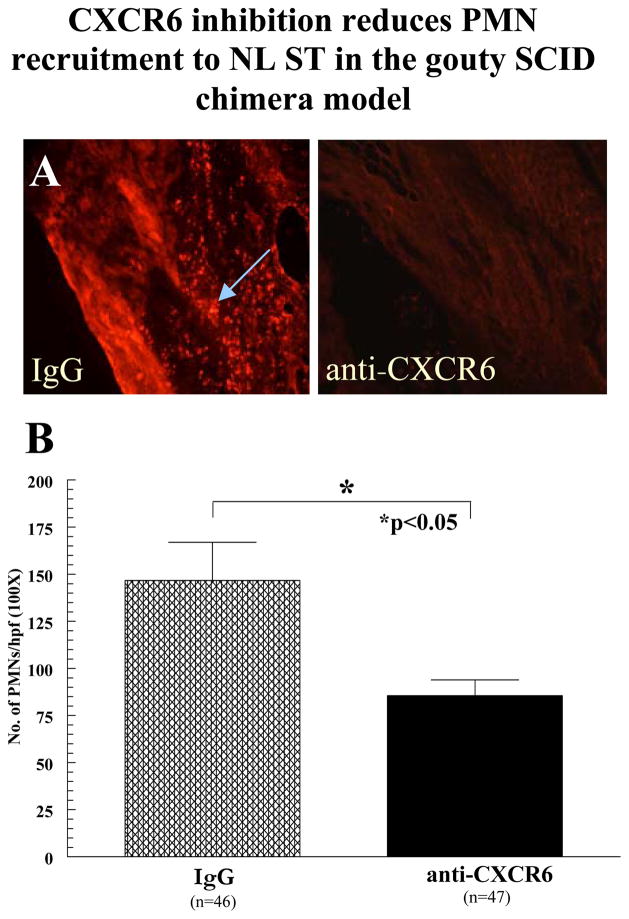

PMNs treated with blocking antibodies to CXCR6 show reduced recruitment to gouty SF injected in NL ST

PMNs were incubated with neutralizing anti-CXCR6, fluorescently dye-tagged, and i.v. injected into SCID mouse chimeras that received intragraft injections (100μl/graft) of diluted gouty SF (1:300 in PBS). After 48 hours, mice were sacrificed and grafts taken for cryosectioning. Control mice received the same intragraft injection of gout SF, but were administered fluorescently dye-tagged PMNs pre-incubated with non-specific IgG (figure 5A). As shown in figure 5B, mice administered PMNs pre-incubated with anti-CXCR6 showed a statistically significant 42% reduction in PMN migration compared to control mice (all data is expressed as mean ± SEM).

Figure 5.

CXCR6 inhibition reduces PMN recruitment to NL ST in the gouty SCID chimera model. A Results are expressed as the mean number of PMNs/hpf (100×; see arrow). The number of hpfs counted was dependent upon the size and composition of the graft and corresponding section. The entire area of each section was counted. Approximately 60–90 hpfs were counted per implant, from at least five independently grafted mice (IgG=5 mice; anti-CXCR6=5 mice). The total number of sections from each mouse constituted the number of samples e.g. approximately fifteen sections/graft from three grafts is 45 sections (n=45). Grafts were surgically removed and set in histology blocks containing OCT. Grafts composed of significant murine tissues were excluded from the study. B A graph of all the data is also presented (error bars represent SEM).

Discussion

Cytokine networks in gout have been insufficiently characterized, although some attempts have been made in animal models (6, 25–28). To identify significant cytokine and chemokine systems, we examined several cytokines by performing Luminex assays on gouty SFs allowing profiling of cytokine expression. These included chemokines, a subset of cytokines that work to induce cell migration to sites of inflammation (16, 19). The CC chemokines measured were CCL2, CCL3 and CCL4. The CXC chemokines included CXCL10, CXCL8 and CXCL16. The latter two were measured by ELISA. We also examined CX3CL1, a chemokine associated with mononuclear cell recruitment and angiogenic activity in RA (20, 29).

First, we showed that CXCL10, CCL2, CXCL16, and the pro-angiogenic factor VEGF were all upregulated compared to a panel of other cytokines measured. Our measurement of CCL2 in gouty SF was comparable to that found previously (30), and likely accounts for many of the recruited monocytes found in gouty SF. We also found that the PMN growth factor G-CSF was upregulated in gouty SF. Second, several of these cytokines are proinflammatory mediators associated with cell recruitment to joint tissues (16, 19). VEGF and CXCL16 are associated with angiogenesis, or new blood vessel growth. Moreover, VEGF has been implicated in wound repair (31), and CXCL16 has been shown to be a very active mononuclear cell recruitment factor in RA (17), as well as having angiogenic activity (32). From our preliminary profile, it is likely that the mediators measured above, in addition to CXCL8, may all be important for cell infiltration to the joints of gout patients (3). We also noted IL-17 is not significantly expressed in gouty SF, in complete agreement with the paucity of lymphocytes found in gouty SFs (data not shown). Interestingly, TNF-α was also not expressed in the gouty SFs we examined (n=7 different specimens), suggesting that the cytokines upregulated in gout possibly function independently of TNF-α. Expression of IL-1β was also relatively low in gouty SF compared to CXCL8 or CXCL16, but has shown to play a more central role than TNF-α in experimental urate crystal induced inflammation (33, 34). Indeed, favorable results have been observed with IL-1 inhibitors to suppress pain and inflammation in small, open label studies in patients with chronic, treatment refractory gouty inflammation (33–35).

CXCL16 was implicated in the early phases of this study as a possible mediator of angiogenesis and cell recruitment in gout. From our data, we have confirmed highly elevated levels of CXCL16 in gouty SFs measuring approximately one hundred-fold greater than many of the other cytokines present. CXCL16 also showed chemotactic properties for PMNs. Indeed, our in vitro chemotaxis findings showed that CXCL16 appears to be a very active PMN recruitment factor in the 1.0nM (10ng/ml) to 10.0nM (100ng/ml) concentration range, consistent with the CXCL16 levels found in gouty SFs (figure 2A).

For the in vivo phase of this study, we depleted upregulated cytokines found in gouty SF and tested their PMN recruitment ability in the SCID mouse chimera system. We found that depleting either gouty SF CXCL16 or membrane bound CXCR6 significantly inhibited in vivo PMN recruitment. Of note was the failure to observe complete inhibition of PMN recruitment in the SCID mouse chimera system. A plausible explanation may be incomplete PMN CXCR6 upregulation, such that only basal levels of PMN CXCR6 accounted for just a fraction of total cellular CXCR6 (36). Using unstimulated PMNs before incubation with anti-CXCR6 supports this. Other factors contributing to incomplete in vivo suppression of PMN migration may be the expression of complement byproducts, or numerous uninhibited chemokines, such as CXCL8, that are also prominent in gouty SF.

Detection of VEGF in gouty SF was somewhat unexpected. Gout is not thought of as a disease dependent upon a high degree of vasculature. However, the cellular infiltrate observed in gouty SF does indicate that cells are migrating freely from the peripheral bloodstream into joint tissues presumably aided by additional vasculature mediated by VEGF expression. Furthermore, monocytes respond, produce and migrate toward VEGF, providing further evidence that recruited monocytes may amplify the angiogenic process in gout. It is tempting to speculate that the effects of VEGF on vascular growth may exacerbate gout pathology. A review of the current literature indicates only a paucity of information linking gout and angiogenesis. However, in a small study, Lapkina et al examined possible laboratory markers of clinical significance of vascular endothelium activation in gout (37). Although the authors did not examine circulating VEGF levels, interestingly, they did show increased serum concentrations of soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and von Willebrand factor (vWF) in gouty patients. This reflected not only activation of vascular endothelium, but also development of atherosclerotic processes in these patients (37). In agreement, Schumacker et al examined a gouty synovial biopsy showing expected robust neutrophil infiltrates, and showed a highly vascularized gouty ST as well (38). We propose that PMN and monocyte recruitment to gouty tissues may rely heavily upon neoangiogenic responses in gouty synovium induced by VEGF, and possibly CXCL16 also found in gouty SF. As CXCL16 is an angiogenic mediator (32), monocyte recruitment factor (17), memory T-cell recruitment factor (39), and a PMN recruitment factor (36), CXCL16 may be a premiere proinflammatory mediator in gout, and would support our premise of significant CXCL16 involvement in gout pathology.

With these experiments, we determined the expression and function of secreted chemotactic factors and their impact on local PMN recruitment in gouty SFs. We have evidence to suggest that chemokines and chemokine receptors, apart from CXCL8, may be at work in gout pathology. We found that CXCL16 is elevated in gouty SFs and that the expression of soluble CXCL16 is at concentrations much higher than CXCL8. This suggests that soluble mediators other than CXCL8 may play a significant role in PMN recruitment caused by MSUM crystal induced inflammatory responses. Overall, we tested our initial in vitro findings with a novel in vivo model for crystal induced arthritis, and related this to CXCL16 expression. Although others have characterized some rudimentary cytokine networks in gout (25), this study was novel in that we examined the nature of PMN recruitment and homing in a human gouty ST SCID mouse chimera. These in vivo experiments built upon our initial findings by examining the activity of CXCL16 and its receptor CXCR6 in an in vivo setting. This allowed for evaluation of the architectural changes in engrafted human NL ST due to PMN migration in response to injected gouty fluid. In conclusion, we mimicked gout pathology with an in vivo model that reproduces this disease with accuracy, aiding the development of therapeutics designed to inhibit proinflammatory factors like CXCL16 that enhance PMN recruitment to gouty tissues.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Inc (JHR, AEK) and by NIH grants RO3AR052482 (MAA) and HL094017 (BJR)

References

- 1.Boisvert WA, Santiago R, Curtiss LK, Terkeltaub RA. A leukocyte homologue of the IL-8 receptor CXCR-2 mediates the accumulation of macrophages in atherosclerotic lesions of LDL receptor-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(2):353–63. doi: 10.1172/JCI1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terkeltaub R, Zachariae C, Santoro D, Martin J, Peveri P, Matsushima K. Monocyte-derived neutrophil chemotactic factor/interleukin-8 is a potential mediator of crystal-induced inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:894–903. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terkeltaub R, Baird S, Sears P, Santiago R, Boisvert W. The murine homolog of the interleukin-8 receptor CXCR-2 is essential for the occurrence of neutrophilic inflammation in the air pouch model of acute urate crystal-induced gouty synovitis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(5):900–9. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<900::AID-ART18>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tramontini N, Huber C, Liu-Bryan R, Terkeltaub RA, Kilgore KS. Central role of complement membrane attack complex in monosodium urate crystal-induced neutrophilic rabbit knee synovitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(8):2633–9. doi: 10.1002/art.20386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishimura A, Akahoshi T, Takahashi M, Takagishi K, Itoman M, Kondo H, et al. Attenuation of monosodium urate crystal-induced arthritis in rabbits by a neutralizing antibody against interleukin-8. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62(4):444–9. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.4.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.So A. Developments in the scientific and clinical understanding of gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(5):221. doi: 10.1186/ar2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hung SI, Chung WH, Liou LB, Chu CC, Lin M, Huang HP, et al. HLA-B*5801 allele as a genetic marker for severe cutaneous adverse reactions caused by allopurinol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(11):4134–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409500102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker MA, Schumacher HR, Jr, Wortmann RL, MacDonald PA, Eustace D, Palo WA, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2450–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becker MA, Schumacher HR, Jr, Wortmann RL, MacDonald PA, Palo WA, Eustace D, et al. Febuxostat, a novel nonpurine selective inhibitor of xanthine oxidase: a twenty-eight-day, multicenter, phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response clinical trial examining safety and efficacy in patients with gout. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(3):916–23. doi: 10.1002/art.20935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, Pascual E, Barskova V, Conaghan P, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: Management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT) Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(10):1312–24. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.055269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richette P, Briere C, Hoenen-Clavert V, Loeuille D, Bardin T. Rasburicase for tophaceous gout not treatable with allopurinol: an exploratory study. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(10):2093–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sundy JS, Ganson NJ, Kelly SJ, Scarlett EL, Rehrig CD, Huang W, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intravenous PEGylated recombinant mammalian urate oxidase in patients with refractory gout. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(3):1021–8. doi: 10.1002/art.22403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganson NJ, Kelly SJ, Scarlett E, Sundy JS, Hershfield MS. Control of hyperuricemia in subjects with refractory gout, and induction of antibody against poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), in a phase I trial of subcutaneous PEGylated urate oxidase. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(1):R12. doi: 10.1186/ar1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Angelis S, Noce A, Di Renzo L, Cianci R, Naticchia A, Giarrizzo GF, et al. Is rasburicase an effective alternative to allopurinol for management of hyperuricemia in renal failure patients? A double blind-randomized study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2007;11(3):179–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chensue SW, Warmington KS, Ruth JH, Sanghi PS, Lincoln P, Kunkel SL. Role of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) in Th1 (mycobacterial) and Th2 (schistosomal) antigen-induced granuloma formation: relationship to local inflammation, Th cell expression, and IL-12 production. J Immunol. 1996;157(10):4602–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katschke KJ, Jr, Rottman JB, Ruth JH, Qin S, Wu L, LaRosa G, et al. Differential expression of chemokine receptors on peripheral blood, synovial fluid, and synovial tissue monocytes/macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(5):1022–32. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<1022::AID-ANR181>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruth JH, Haas CS, Park CC, Amin MA, Martinez RJ, Haines GK, 3rd, et al. CXCL16-mediated cell recruitment to rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissue and murine lymph nodes is dependent upon the MAPK pathway. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(3):765–78. doi: 10.1002/art.21662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruth JH, Lukacs NW, Warmington KS, Polak TJ, Burdick M, Kunkel SL, et al. Expression and participation of eotaxin during mycobacterial (type 1) and schistosomal (type 2) antigen-elicited granuloma formation. J Immunol. 1998;161(8):4276–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruth JH, Rottman JB, Katschke KJJ, Qin S, Wu L, LaRosa G, et al. Selective lymphocyte chemokine receptor expression in the rheumatoid joint. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(12):2750–60. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2750::aid-art462>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruth JH, Volin MV, Haines GK, 3rd, Woodruff DC, Katschke KJ, Jr, Woods JM, et al. Fractalkine, a novel chemokine in rheumatoid arthritis and in rat adjuvant-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(7):1568–81. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200107)44:7<1568::AID-ART280>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruth JH, Bullard DC, Haas CS, Park CC, Koch AE. Accelerated inflammation, increased severity, and enhanced recruitment of peritoneal macrophages to the joints of mice deficient in E- and P-selectins. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:S274. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar P, Hosaka S, Koch AE. Soluble E-selectin induces monocyte chemotaxis through Src family tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21039–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruth JH, Shahrara S, Park CC, Morel JC, Kumar P, Qin S, et al. Role of macrophage inflammatory protein-3alpha and its ligand CCR6 in rheumatoid arthritis. Lab Invest. 2003;83(4):579–88. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000062854.30195.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terkeltaub R, Baird S, Sears P, Santiago R, Boisvert W. The murine homolog of the interleukin-8 receptor CXCR-2 is essential for the occurrence of neutrophilic inflammation in the air pouch model of acute urate crystal-induced gouty synovitis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1998;41(5):900–9. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<900::AID-ART18>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsukawa A, Miyazaki S, Maeda T, Tanase S, Feng L, Ohkawara S, et al. Production and regulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in lipopolysaccharide- or monosodium urate crystal-induced arthritis in rabbits: roles of tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-1, and interleukin-8. Lab Invest. 1998;78(8):973–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Giovine FS, Malawista SE, Nuki G, Duff GW. Interleukin 1 (IL 1) as a mediator of crystal arthritis: Stimulation of T cell and synovial fibroblast mitogenesis by urate crystal-induced IL 1. J Immunol. 1987;138:3213–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu-Bryan R, Scott P, Sydlaske A, Rose DM, Terkeltaub R. Innate immunity conferred by Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 and myeloid differentiation factor 88 expression is pivotal to monosodium urate monohydrate crystal-induced inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(9):2936–46. doi: 10.1002/art.21238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott P, Ma H, Viriyakosol S, Terkeltaub R, Liu-Bryan R. Engagement of CD14 mediates the inflammatory potential of monosodium urate crystals. J Immunol. 2006;177(9):6370–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Volin MV, Woods JM, Amin MA, Connors MA, Harlow LA, Koch AE. Fractalkine: a novel angiogenic chemokine in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(4):1521–30. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62537-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harigai M, Hara M, Yoshimura T, Leonard EJ, Inoue K, Kashiwazaki S. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) in inflammatory joint diseases and its involvement in the cytokine network of rheumatoid synovium. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;69:83–91. doi: 10.1006/clin.1993.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nissen NN, Polverini PJ, Koch AE, Volin MV, Gamelli RL, DiPietro LA. Vascular endothelial growth factor mediates angiogenic activity during the proliferative phase of wound healing. Am J Pathol. 1998;152(6):1445–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhuge X, Murayama T, Arai H, Yamauchi R, Tanaka M, Shimaoka T, et al. CXCL16 is a novel angiogenic factor for human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331(4):1295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terkeltaub R. Update on gout: new therapeutic strategies and options. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 6(1):30–8. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.So A, De Smedt T, Revaz S, Tschopp J. A pilot study of IL-1 inhibition by anakinra in acute gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(2):R28. doi: 10.1186/ar2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terkeltaub R, Sundy JS, Schumacher HR, Murphy F, Bookbinder S, Biedermann S, et al. The interleukin 1 inhibitor rilonacept in treatment of chronic gouty arthritis: results of a placebo-controlled, monosequence crossover, non-randomised, single-blind pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(10):1613–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaida MM, Gunther F, Wagner C, Friess H, Giese NA, Schmidt J, et al. Expression of the CXCR6 on polymorphonuclear neutrophils in pancreatic carcinoma and in acute, localized bacterial infections. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;154(2):216–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lapkina NA, Baranov AA, Barskova VG, Abaitova NE, Iakunina IA. Markers of vascular endothelium activation in gout. Ter Arkh. 2005;77(5):62–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schumacher HR., Jr The pathogenesis of gout. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75 (Suppl 5):S2–4. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.75.suppl_5.s2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Voort R, van Lieshout AW, Toonen LW, Sloetjes AW, van den Berg WB, Figdor CG, et al. Elevated CXCL16 expression by synovial macrophages recruits memory T cells into rheumatoid joints. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(5):1381–91. doi: 10.1002/art.21004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]