Abstract

Purpose

There is, in European countries that conduct medical chart review of intensive care unit (ICU) deaths, no consensus on uniform criteria for defining a potential organ donor. Although the term is increasingly being used in recent literature, it is seldom defined in detail. We searched for criteria for determination of imminent brain death, which can be seen as a precursor for organ donation.

Methods

We organized meetings with representatives from the field of clinical neurology, neurotraumatology, intensive care medicine, transplantation medicine, clinical intensive care ethics, and organ procurement management. During these meetings, all possible criteria were discussed to identify a patient with a reasonable probability to become brain dead (imminent brain death). We focused on the practical usefulness of two validated coma scales (Glasgow Coma Scale and the FOUR Score), brain stem reflexes and respiration to define imminent brain death. Further we discussed criteria to determine irreversibility and futility in acute neurological conditions.

Results

A patient who fulfills the definition of imminent brain death is a mechanically ventilated deeply comatose patient, admitted to an ICU, with irreversible catastrophic brain damage of known origin. A condition of imminent brain death requires either a Glasgow Coma Score of 3 and the progressive absence of at least three out of six brain stem reflexes or a FOUR score of E0M0B0R0.

Conclusion

The definition of imminent brain death can be used as a point of departure for potential heart-beating organ donor recognition on the intensive care unit or retrospective medical chart analysis.

Keywords: Brain death, Critical care organisation, Neurotrauma, Transplantation, Stroke, Emergency medicine

Introduction

Organ transplantation is often the last resort for patients with end-stage organ failure. The number of patients waiting for one or more organ(s) is still increasing in the USA and Europe [1–3]. Brain(stem) dead patients provide the major source of solid organs for transplantation [4, 5]. Unfortunately, for potential organ recipients, brain(stem) death is a rare form of death. Among 4,248 patients who died on European intensive care units (ICUs) in an 18-month period, only 330 patients (7.8%) were diagnosed brain(stem) dead [6].

Since the first descriptions of brain(stem) death in the late 1950s [7, 8], and the first formal definition of brain(stem) death by the Harvard Committee in 1968 [9], many thousands of patients have been declared dead worldwide each year, based on formal brain(stem) death criteria. Today, brain(stem) death is recognised as legal death in most western countries [10]. The causes of brain(stem) death vary, but approximately 80–90% of patients who develop brain(stem) death are admitted to an ICU with traumatic brain injury (TBI), subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) or intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH) [5, 11]. Other less frequent causes are post-resuscitation encephalopathy, an intracranial tumour or central nervous system infections.

Current practice in organ donation is based on the “dead-donor-rule” as described by Robertson [12]. As the shortage of organs has become more critical, proposals have been put forth to increase the potential pool of organ donors. Some of these proposals simply abandon the dead donor rule by redefining certain categories of patients (e.g., patients in persistent vegetative state [13] or anencephalic patients) as dead for donation purposes [10, 14]. In order to improve the supply of organ donation, but not violate the dead donor rule, we have to examine how to increase the conversion rate between potential organ donors and actual organ donors. Many patients with a hopeless neurological prognosis are not identified as possible brain dead organ donors. Other patients deteriorate between the period of possible brain death recognition and a formal brain(stem) death diagnosis [5, 15–17]. Timely referral of potential organ donors to representatives of an organ procurement organisation (OPO) is essential for this reason [18]. The decision whether or not to continue life-sustaining treatment of a patient with severe brain damage in the ICU is primarily dependent upon the estimated outcome. A large proportion of these deaths occur in the context of withdrawing life-sustaining treatment, especially when catastrophic neurologic injuries leave little to no chance of meaningful recovery [19, 20]. However, when such a patient is identified as a potential organ donor, treatment is generally continued until brain(stem) death has been definitively established. Potential organ donors should therefore be identified as soon as possible, and the possible diagnosis of brain(stem) death should never be missed or delayed.

This area of improvement has not gone unnoticed by several national procurement organisations and collaborations [21, 22]. The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) in the USA developed the term “imminent neurological death” (see http://www.optn.transplant.hrsa.gov). According to article 7.1.7, as published on their website, a patient with imminent neurological death is defined as “a patient who is 70 years old or younger with severe neurological injury and requiring ventilator support who, upon clinical evaluation…has an absence of at least three brainstem reflexes”. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is for unknown reasons not incorporated in this definition. The OPTN definition is solely used for data submission and analysis, and is, to our best knowledge, not used for clinical recognition of potential organ donors. A European Consortium of organ procurement organisations (the DOPKI project) funded by the European Commission tried to find a widely agreed upon methodology to estimate the potential of deceased organ donors. The goal of the DOPKI project is to develop Quality Assurance Programmes that can be used to make international comparisons possible [22]. Until now there is no published peer-reviewed report of this methodology. Nevertheless, we strongly subscribe to the latter argument. Obtaining insight into organ donation performances, the strength and weakness of the donation process and to benchmark donation performance on a hospital, regional and national level is relevant. Early recognition by a clinician of a patient’s impending hopeless clinical neurological condition in order to preserve organs [23–25] and to facilitate organ donation is of even greater relevance. The gained extra time can be used to ensure that families are provided with the opportunity to consider organ donation based on correct information. Families have time to understand and accept the fact that their loved one is brain dead. In addition to this, it offers clinicians the opportunity to give information about brain death and the request organ donation in two separate meetings, both of which can have a significant impact on the rates of consent [18, 26]. However, the identification of a potential organ donor does not discharge a physician from treating the patient in the patients’ best interest.

In this article we propose criteria for the definition of a potential organ donor based on multi-disciplinary consensus among experts. The goal is to propose a definition that can be used for clinical purposes and for retro- and prospective data analysis.

We wish to emphasise that this initiative was undertaken from the perspective of achieving a more consistent and reliable estimation of the number of potential organ donors and an easy-to-use referral tool for OPOs. In this article, we will give criteria for the determination of, what we will call ‘Imminent Brain Death’. We strongly state that the proposed definition should not be considered equivalent to ‘brain(stem) death’ and that the designation of a patient with imminent brain death represents no more than a certain risk estimate. Per definition, the assessment of imminent brain death should not lead to withdrawal of treatment. In fact, identifying a patient’s situation as imminent brain death may delay or cancel the option to withdraw life support, and add an expressed option to wait for brain death, in order to preserve donor organs. Treatment-limiting decisions remain the responsibility of the clinician, who should base his decisions as much as possible on evidence-based risk estimates, taking opinions of relatives and autonomy of patients into account.

Materials and methods

We organised expert meetings with representatives from the field of clinical neurology (MAK, HPHK), neurotraumatology (AIRM), intensive care medicine (YJdG; JB, SA, MAK, EFMW, EJOK), transplantation medicine (AJH), clinical intensive care ethics (EJOK) and organ procurement management (NEJ, HAvL). EFMW participated by e-mail.

During these meetings, all possible criteria were discussed to identify a patient with a reasonable probability to become brain(stem) dead, in other words, to be in a state of imminent brain death. We focused on the practical usefulness of two validated coma scales (Glasgow Coma Scale and the FOUR Score), brainstem reflexes and respiration to define imminent brain death. Further we discussed criteria to determine irreversibility and futility in acute neurological conditions.

Results

First, only ventilator-dependent patients admitted to an ICU with a known origin of catastrophic brain damage, and whose condition is considered irreversible and for whom no treatment possibilities are left, can fall within the definition of imminent brain death. Establishing irreversibility requires repeated examinations and exclusion of major confounders, such as effects of sedation and hypothermia. This may include multidisciplinary assessment by physicians in intensive care medicine, neurology and neurosurgery.

Imminent brain death implies generalised loss of cortical function and progressive brainstem failure. Complete loss of consciousness is thus a prerequisite when considering imminent brain death. The most commonly used scale for assessment of coma is the Glasgow Coma Scale, which was proposed in 1974 as a practical tool for diagnosis and prognosis of cerebral function of patients with traumatic brain injury [27]. In most countries, the GCS is the gold standard for assessing the level of consciousness in patients with acute brain damage. The total GCS is the sum of scores in three categories: eye opening, motor response and verbal response. Using the GCS, the patient with imminent brain death has no eye movement (E1), no motor response (M1) and no verbal response (V1). We recognise that patients in whom a condition of imminent brain death is suspected are mechanically ventilated, thus rendering reliable estimation of the verbal score nearly impossible. In the absence of any other indication of responsiveness, the verbal reaction can be considered absent in these patients.

Before brainstem failure can be assessed, confounding factors (e.g. hypothermia, metabolic disturbances and sedation) should be excluded. Brainstem failure is determined by the absence of all brainstem reflexes. The most relevant brainstem reflexes to this purpose are: pupillary reactivity to light, corneal reflex, oculocephalic and oculovestibular responses, gag and cough reflex.

First, based on the GCS and examination of brainstem reflexes, imminent brain death can be defined as: ‘A state in which a deeply comatose, mechanically ventilated patient, admitted to an ICU, with irreversible catastrophic brain damage of known origin (e.g. TBI, SAH, ICH) has a GCS of 3 (E1, M1, V1) and at least three or more absent brainstem reflexes’.

The rationale to chose three or more absent brainstem reflexes is to reflect the severity of brainstem lesions [28]. We opted not to establish a hierarchy or ranking of absent brainstem reflexes as in clinical practice different sequences of progressive brainstem reflexes failure may occur [25, 29]. In this way every patient with some form of cerebral herniation and brainstem failure that can lead to brain death can be included in this definition and analysis of potential organ donors.

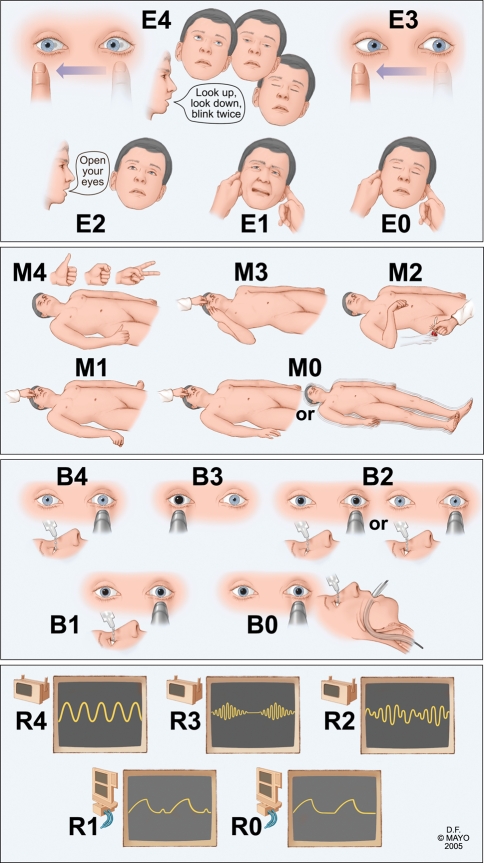

An attractive alternative to the use of the GCS and brainstem reflexes is offered by the FOUR score [30–35]. The FOUR stands for Full Outline of UnResponsiveness. The FOUR score has four testable components, and the maximal grade in each of the categories is four (Fig. 1). It includes the Eye response, Motor response, Brainstem reflexes and Respiration. As the FOUR score includes the essential parts of the GCS, brainstem reflexes and respiration, this coma scale can be very useful for the determination of imminent brain death.

Fig. 1.

Description of Full Outline of UnResponsivenes (FOUR) score. Eye response: E4 eyelids open or opened, tracking or blinking to command; E3 eyelids open but not tracking; E2 eyelids closed but open to loud voice; E1 eyelids closed but open to pain; E0 eyelids remain closed with pain. Motor response: M4 thumbs-up, fist or peace sign; M3 localising to pain; M2 flexion response to pain; M1 extension response to pain; M0 no response to pain or generalised myoclonus status. Brainstem reflexes: B4 pupil and corneal reflexes present; B3 one pupil wide and fixed; B2 pupil or corneal reflexes absent; B1 pupil and corneal reflexes absent; B0 absent pupil, corneal and cough reflex. Respiration pattern: R4 not intubated, regular breathing pattern; R3 not intubated, Cheyne-Stokes breathing pattern; R2 not intubated, irregular breathing; R1 breathes above ventilatory rate; R0 breathes at ventilator rate or apnea

In analogy with the definition of imminent brain death using the GCS, a patient with imminent brain death will have a FOUR score of E0 (eyelids remain closed with pain), M0 (no response to pain or generalised myoclonus status), B0 (pupil, corneal and cough reflexes absent) and R0 (breathes at ventilator rate or apnoea). The FOUR score includes three brainstem reflexes, pupillary response, corneal and cough reflexes, in the category brainstem reflexes; in B0 all three reflexes are absent, and in B1 only the pupil and corneal reflex are absent. In the category B1, patients can have absent pontomesencephalic reflexes but retained the cough reflex and some respiratory drive (E0M0B1R1). These patients may or may not progress to full brain death. Loss of the last two points in time will make it likely that these patients will become brain dead. Some patients stop at E0M0B1R1 and do not progress to full brain death. For this reason, we propose, for the definition of imminent brain death, a FOUR score of E0M0B0R0, and not E0M0B1R0 or E0M0B1R1. One patient with a FOUR score of 0 is described, showing retained isolated medullary function [36]; this patient did not progress to loss of all brainstem function. One may conclude that predictive factors for loss of all brainstem function have not yet been identified. Iyer et al. [37] showed that patients with a FOUR score of 0 had a mortality of 89%; eight out of nine patients died.

As the FOUR score is used in many ICUs and captures information on both levels of consciousness and brainstem reflexes, we consider this score more useful than the GCS alone, when considering a diagnosis of imminent brain death.

As a definition for imminent brain death we propose:

‘A mechanically ventilated, deeply comatose patient, admitted to an ICU, with irreversible catastrophic brain damage of known origin (e.g. TBI, SAH, ICH). A condition of imminent brain death requires either a GCS of 3 and the progressive absence of at least three out of six brainstem reflexes, or a FOUR score of E 0 M 0 B 0 R 0 ’.

Formal whole brain death or brainstem death can only be determined after conformation of the absence of all brainstem reflexes and ancillary tests like the EEG and apnoea test (which are mandatory in several EU countries).

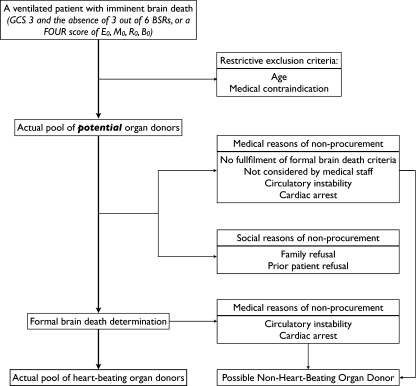

Analysis of the pool of patients, who meet the criteria of imminent brain death, should be conducted in a hierarchical order (Fig. 2). Some parameters, such as age and medical condition, are restrictive exclusion criteria. In most countries, a patient fulfilling the definition of imminent brain death, but who is older than, e.g., 75 years, will not be considered as a potential organ donor. The same holds for some medical reasons for exclusion, such as severe viral, bacterial or fungal infections and malignant neoplasm. These factors cannot be modified. After excluding the patients with these characteristics, the result is the actual pool of potential organ donors who fit every medical criterion to become a heart-beating organ donor.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of potential organ donors

Discussion

The proposed definition can be used as a point of departure for retrospective chart analysis, as recognition for potential organ donors for prospective determination and, derived from this, the estimation of the number of potential organ donors and its conversion rate in actual organ donors. The definition can also be used as a clinical recognition tool.

If a patient, who meets every criterion of a potential heart-beating organ, does not become a donor, it is de facto because of factors on a medical level or on a social level. Reasons on a medical level are patients who do not fulfil the formal criteria for complete brain death, are not considered or recognised by physicians and nurses, or who suffer from circulatory instability or cardiovascular arrest during the procedure. However, these patients could become non-heart beating organ donors, if logistically possible, after they died of circulatory arrest. Optimisation of the haemodynamic system and overall physiology of patients with imminent brain death will decrease the number of donors lost for this reason [23, 25]. Education of physicians and nurses has been shown to be an improvement for consent rates [38]. Reasons of non-procurement on a social level include family refusal or prior patient refusal. These reasons are modifiable by education of the general population to increase awareness and understanding of brain death [39, 40]. Targeting such education campaigns appropriately requires insight into the relative contribution of medical and social attitudes on non-organ procurement.

Simpkin et al. [26] and Siminoff et al. [39] both evaluated the factors that influence relatives’ consent for donation of solid organs. Families were more willing to give consent for donation when they had been given enough information about brain death and the donation process to make an informed decision. The time given to families to make the decision was also an important factor in the discussion and consent process of a family. With timely recognition of a potential organ donor and adequate specialised care to preserve the organs for donation, should that be the case, it is possible to offer families information and time for ample discussion.

We choose to make a more strict definition of a potential organ donor than, for example, the OPTN criteria. The reason for this is twofold. First, with a stricter definition, used as clinical recognition tool and referral tool, the sparse resources of an OPO (and ICU) will only be deployed for those patients with the highest chance to become brain(stem) dead and eventually, if consent is given, become a donor. Second, systematic chart reviews for measuring the actual potential for organ donation has become the gold standard in the US and Europe [41]. With this in mind, we aimed to develop a tool that measures a realistic pool of potential organ donors and thus a realistic conversion rate that can be widely applied. We think that our proposal is open for debate by the professionals and procurement organisations. One of the aims of this paper is to engage a discussion about the potential of heart-beating organ donors in a group with a hopeless neurological outcome.

Conclusion

In this article we propose criteria for determination of Imminent Brain Death and a practical, widely applicable definition of a potential organ donor based on unambiguous criteria for imminent brain death, which can be seen as a precursor for organ donation. The definition of imminent brain death can be used as a starting point for potential organ donor recognition on the ICU or retrospective medical chart analysis. Further study is needed to determine how many patients fulfilling the definition of imminent brain death will actually become organ donors.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Annual Report of the US Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (2007) Transplant data 1997–2006. Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation. http://www.optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/annualReport.asp. Accessed 28 July 2009

- 2.Transplant activity in the UK 2007–2008 (2008) NHS blood and transplant. http://www.uktransplant.org.uk/ukt/statistics/statistics.jsp. Accessed 27 July 2009

- 3.Annual Report (2008) Eurotransplant International Foundation. http://www.eurotransplant.nl/files/annual_report/ar_2008.pdf. Accessed 28 July 2009

- 4.Tuttle-Newhall JE, Krishnan SM, Levy MF, McBride V, Orlowski JP, Sung RS. Organ donation and utilization in the United States: 1998–2007. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:879–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kompanje EJ, Bakker J, Slieker FJ, IJzermans JN, Maas AI. Organ donations and unused potential donations in traumatic brain injury, subarachnoid haemorrhage and intracerebral haemorrhage. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:217–222. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-0001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sprung CL, Cohen SL, Sjokvist P, Baras M, Bulow HH, Hovilehto S, Ledoux D, Lippert A, Maia P, Phelan D, Schobersberger W, Wennberg E, Woodcock T. End-of-life practices in European intensive care units: the Ethicus Study. JAMA. 2003;290:790–797. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.6.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mollaret P, Goulon M. The depassed coma (preliminary memoir) Rev Neurol (Paris) 1959;101:3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wertheimer P, Jouvet M, Descotes J. Diagnosis of death of the nervous system in comas with respiratory arrest treated by artificial respiration. Presse Med. 1959;67:87–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(1968) A definition of irreversible coma. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to examine the definition of brain death. JAMA 205:337–340 [PubMed]

- 10.Siminoff LA, Burant C, Youngner SJ. Death and organ procurement: public beliefs and attitudes. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:2325–2334. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wijdicks EF, Pfeifer EA. Neuropathology of brain death in the modern transplant era. Neurology. 2008;70:1234–1237. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000289762.50376.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robertson JA. The dead donor rule. Hastings Cent Rep. 2000;29:6–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffenberg R, Lock M, Tilney N, Casabona C, Daar AS, Guttmann RD, Kennedy I, Nundy S, Radcliffe-Richards J, Sells RA. Should organs from patients in permanent vegetative state be used for transplantation? International Forum for Transplant Ethics. Lancet. 1997;350:1320–1321. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molina A, Rodriguez-Arias D, Youngner SJ. Should individuals choose their definition of death? J Med Ethics. 2008;34:688–689. doi: 10.1136/jme.2007.022921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barber K, Falvey S, Hamilton C, Collett D, Rudge C. Potential for organ donation in the United Kingdom: audit of intensive care records. BMJ. 2006;332:1124–1127. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38804.658183.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gortmaker SL, Beasley CL, Brigham LE, Franz HG, Garrison RN, Lucas BA, Patterson RH, Sobol AM, Grenvik NA, Evanisko MJ. Organ donor potential and performance: size and nature of the organ donor shortfall. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:432–439. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199603000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Opdam HI, Silvester W. Identifying the potential organ donor: an audit of hospital deaths. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1390–1397. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shafer TJ. Improving relatives’ consent to organ donation. BMJ. 2009;338:b701. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan JD, Treece PD, Engelberg RA, Crowley L, Rubenfeld GD, Steinberg KP, Curtis JR. Narcotic and benzodiazepine use after withdrawal of life support: association with time to death? Chest. 2004;126:286–293. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.1.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook D, Rocker G, Marshall J, Sjokvist P, Dodek P, Griffith L, Freitag A, Varon J, Bradley C, Levy M, Finfer S, Hamielec C, McMullin J, Weaver B, Walter S, Guyatt G. Withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in anticipation of death in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1123–1132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy C, Hamilton C (2008) Potential donor audit summary report for the 24 month period 1 April 2006–31 March 2008. NHS blood and transplant. http://www.uktransplant.org.uk/ukt/statistics/potential_donor_audit/pdf/pda_summary_report_2006-2008.pdf. Accessed 28 July 2009

- 22.Margarida A, Brezovsky P, Czerwinski J et al (2009) Guide of recommendations for quality assurance programmes in the deceased donation process. DOPKI. http://www.dopki.eu/DOPKI_Guide.pdf. Accessed 28 July 2009

- 23.Wood KE, Becker BN, McCartney JG, D’Alessandro AM, Coursin DB. Care of the potential organ donor. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2730–2739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra013103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lytle FT, Afessa B, Keegan MT. Progression of organ failure in patients approaching brain stem death. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(6):1446–1450. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood KE, Coursin DB. Intensivists and organ donor management. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2007;20:97–99. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3280895ac8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simpkin AL, Robertson LC, Barber VS, Young JD. Modifiable factors influencing relatives’ decision to offer organ donation: systematic review. BMJ. 2009;338:b991. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2:81–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wedekind C, Hesselmann V, Lippert-Gruner M, Ebel M. Trauma to the pontomesencephalic brainstem—a major clue to the prognosis of severe traumatic brain injury. Br J Neurosurg. 2002;16:256–260. doi: 10.1080/02688690220148842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenberg RN. Consciousness, coma, and brain death—2009. JAMA. 2009;301:1172–1174. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lovegrove C. The FOUR score: a new scale for improved assessment of coma. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2006;2:4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stead LG, Wijdicks EF, Bhagra A, Kashyap R, Bellolio MF, Nash DL, Enduri S, Schears R, William B. Validation of a new coma scale, the FOUR score, in the emergency department. Neurocrit Care. 2009;10:50–54. doi: 10.1007/s12028-008-9145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wijdicks EF. Clinical scales for comatose patients: the Glasgow Coma Scale in historical context and the new FOUR Score. Rev Neurol Dis. 2006;3:109–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wijdicks EF, Bamlet WR, Maramattom BV, Manno EM, McClelland RL. Validation of a new coma scale: the FOUR score. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:585–593. doi: 10.1002/ana.20611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wijdicks EFM. The comatose patient. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolf CA, Wijdicks EF, Bamlet WR, McClelland RL. Further validation of the FOUR score coma scale by intensive care nurses. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:435–438. doi: 10.4065/82.4.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wijdicks EF, Atkinson JL, Okazaki H. Isolated medulla oblongata function after severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:127–129. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.1.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iyer VN, Mandrekar JN, Danielson RD, Zubkov AY, Elmer JL, Wijdicks EF. Validity of the FOUR score coma scale in the medical intensive care unit. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:694–701. doi: 10.4065/84.8.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riker RR, White BW. The effect of physician education on the rates of donation request and tissue donation. Transplantation. 1995;59:880–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siminoff LA, Gordon N, Hewlett J, Arnold RM. Factors influencing families’ consent for donation of solid organs for transplantation. JAMA. 2001;286:71–77. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Howard RJ. Organ donation decision: comparison of donor and nondonor families. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:190–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01130.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roels L, Cohen B, Gachet C. Countries’ donation performance in perspective: time for more accurate comparative methodologies. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1439–1441. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]