Abstract

Alternatively activated macrophages prevent lethal intestinal pathology caused by worm ova in mice infected with the human parasite Schistosoma mansoni through mechanisms that are currently unclear. This study demonstrates that arginase I (Arg I), a major product of IL-4– and IL-13–induced alternatively activated macrophages, prevents cachexia, neutrophilia, and endotoxemia during acute schistosomiasis. Specifically, Arg I-positive macrophages promote TGF-β production and Foxp3 expression, suppress Ag-specific T cell proliferation, and limit Th17 differentiation. S. mansoni-infected Arg I-deficient bone marrow chimeras develop a marked accumulation of worm ova within the ileum but impaired fecal egg excretion compared with infected wild-type bone marrow chimeras. Worm ova accumulation in the intestines of Arg I-deficient bone marrow chimeras was associated with intestinal hemorrhage and production of molecules associated with classical macrophage activation (increased production of IL-6, NO, and IL-12/IL-23p40), but whereas inhibition of NO synthase-2 has marginal effects, IL-12/IL-23p40 neutralization abrogates both cachexia and intestinal inflammation and reduces the number of ova within the gut. Thus, macrophage-derived Arg I protects hosts against excessive tissue injury caused by worm eggs during acute schistosomiasis by suppressing IL-12/IL-23p40 production and maintaining the Treg/Th17 balance within the intestinal mucosa.

Interleukin-4 and IL-13 protect hosts against a variety of parasitic helminths by signaling through IL-4Rα–chain (IL-4Rα) on both bone marrow (BM)- and non–BM-derived cells (1). Macrophages (Mφs) activated through IL-4Rα suppress lethal inflammation caused by worm ova produced by Schistosoma mansoni, a tropical parasitic helminth that causes lung, liver, and intestinal fibrotic granulomas in 250 million people worldwide (2, 3). IL-4Rα– dependent alternatively activated Mφs (AAMφs) may downregulate S. mansoni-induced inflammation during acute schistosomiasis (7–9 wk postinfection) through production of immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β that antagonize IL-17–associated neutrophilia and tissue injury (4). AAMφs could also inhibit the differentiation of classically activated Mφs (CAMφs), which secrete proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-12/IL-23p40, and produce reactive nitrogen and oxygen intermediates that cause oxidative tissue damage (5). In contrast, IL-4Rα–mediated signaling induces debilitating liver fibrosis during chronic S. mansoni infection (>12 wk postinfection) (6), which suggests that the Th2 response provides a selective advantage for the host that prevents rapid lethality at the expense of chronic morbidity.

Arginase I (Arg I) is an enzyme postulated to downregulate inflammatory responses and facilitate tissue remodeling, because it competes with inducible NO synthase-2 (NOS-2) for L-arginine and initiates the pathways that lead to synthesis of proline and polyamines (7).Mφ Arg I production is strongly stimulated by IL-4/IL-13 during helminth infections, although it can also be induced to a limited extent by unicellular pathogens through a STAT-6–independent pathway (8). Mφ-derived Arg I has recently been shown to decrease chronic immunopathology in S. mansoni-infected mice by suppressing Th2 cell expansion and reducing chronic liver fibrosis (9). However, because IL-4/IL-13–induced Arg I may antagonize classical Mφ activation during acute infection with S. mansoni (10), we asked whether Arg I also protects against acute immunopathology initiated by worm ova deposition in host tissues. Indeed, S. mansoni-infected chimeric mice lacking Arg I in BM-derived cells develop IL-12/IL-23p40– dependent neutrophil-associated gut pathology, intestinal hemorrhage, and endotoxemia. This suggests that AAMφ production of Arg I is a host protective mechanism that restricts tissue damage induced by worm ova during their excretion from blood vessels into the intestinal lumen by downregulating production of IL-12 and/or IL-23 that would otherwise cause lethal intestinal inflammation.

Materials and Methods

Mice and S. mansoni infection

Sex-matched 6- to 8-wk-old BALB/c male wild-type (WT) and IL-4Rα– deficient mice were purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY) and used for BM chimera generation and experiments that involved treatment with arginase or NO synthetase antagonists. Efficiency of donor chimerism was determined by evaluation of IL-4Rα surface staining by flow cytometry as described previously (11). WT C57BL/6 (CD45.1) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), and sex-matched animals were used as recipients of BM isolated from Arg I−/− or heterozygous Arg I+/− (postnatal days 9–12) mice (CD45.2). Recipients were sublethally irradiated (1175 rad of [137Cs]) and reconstituted with 1 × 106 total BM cells, and donor chimerism was evaluated 10 wk later via flow cytometry using splenocytes stained with allotype-specific Abs that recognized CD45.1 or CD45.2 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Mice that showed <95% donor chimerism were excluded from further experimental analysis. Mice were anesthetized and percutaneously infected with 50–70 S. mansoni cercariae (11) from snails that were provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Schistosomiasis Resource Center through NIAID Contract N0-AI-30026.

Determination of chimerism via flow cytometry

PBMCs or splenocytes were isolated by Ficoll gradient, after which splenocytes were washed in FACS buffer (HBSS, 1% FCS, and 0.2% sodium azide) and incubated with anti-FcγRII/RIII mAb (2.4G2). PBMCs were stained with fluorochrome-labeled rat mAbs to mouse CD11b (M1/70) or the allotypic markers CD45.1 and CD45.2 (BD Pharmingen). Cells were then stained with the mAbs and analyzed with BD FACSCalibur and CellQuest software. Percent donor cells were calculated as described previously (11).

T cell proliferation via CFSE dilution

Naive CD4+ cells were isolated from single-cell suspensions of lymph node and spleen from 6- to 8-wk-old OVA-specific TCR transgenic mice (OTII), using an anti–CD4-labeled magnetic microbead (clone L3T4)-based MACS separator system (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Purity was ~90% as determined by flow cytometry. Isolated CD4+ cells were incubated with 10 µM CFSE (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in sterile Dulbecco’s PBS at 37°C for 10 min, quenched with 3% BSA/PBS, and used for Mφ coculture experiments.

Mφ-T cell coculture

Mφs were derived from BM by culturing in DMEM with 10% FCS and L-glutamine, supplemented with supernatant from an M-CSF–producing cell line (CMG, 1/32 dilution of supernatant). On day 3, differentiated Mφs were harvested with 0.05% trypsin, and 0.02% EDTA and M-CSF–containing medium were replaced with fresh D-10 medium with M-CSF. On day 5,Mφs (1 × 105/well) were either left untreated or pulsed with 50 µg/well OVA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) overnight, washed several times, and co-cultured with purified naive OT-II CD4+ cells at a ratio of 10:1 (CD4+/Mφ) for 96 h. Cell supernatants were removed at 96 h and stored at −80°C prior to analysis by ELISA. Cells were harvested, stained with APC-conjugated anti-CD4 (clone GK1.5) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and 7-aminoactinomycin D (Sigma-Aldrich), and evaluated for CFSE mean fluorescence intensity of events within the CD4+ T cell gate.

Determination of S. mansoni tissue egg burden, granuloma measurement, and immunohistochemistry

Biopsies of liver and intestine (ileum) were collected from each mouse, weighed, and digested in 5% KOH at 37°C for 16 h, and eggs were counted at ×40 magnification. Data are expressed as eggs per gram of tissue. For granuloma size determination, 10% formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded organs were histologically processed into sections of liver or intestinal tissue that were cut at 5 µm and stained with H&E. Individual granuloma areas were measured on coded slides; only granulomas that possessed a central egg were evaluated. Quantitation of area was performed using an SPT Diagnostics imaging system and Simple PCI C-Imaging systems software (SDR Clinical Technology, Cranberry Township, PA) for granuloma area measurement. Data shown are mean ± SE of 150 granulomas/group from two independent experiments. Arg I immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin-embedded sections. Citric acid-based Ag retrieval was used, and sections were incubated with the mouse on mouse blocking kit and an avidin/biotin complex staining kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) used for diaminobenzidine-based detection.

Fecal egg quantification

Fecal egg number was determined as described previously (10). In brief, fecal pellets from individual mice at 8 wk postinfection were collected and weighed. Feces were homogenized in cold 2× PBS and centrifuged at 500 × g at 4°C. Pellets were reconstituted in fresh 2× PBS, after which a fecal slurry was spread over a petri dish, and eggs were counted using a stereomicroscope at ×10 magnification. Data are expressed as eggs per gram of feces.

Real-time PCR

RNA was obtained from intestinal tissue and DNAse I-treated cDNA was generated using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was carried out on a Gene Amp 7500 instrument (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with the Sybr Green detection reagent. Cycle threshold values for genes evaluated were determined, and fold induction was compared with vimentin using the 1/Δct method. The sequences are as follows: vimentin, 5′-GTG CGC CAG CAG TAT GAA AG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCA TCG TTG TTC CGG GTT GG-3′ (reverse); Arg I, 5′-CAG AAG AAT GGA AGA GTC AG-3′ (forward) and 5#x02032;-CAG ATA TGC AGG GAG TCA CC-3′ (reverse); resistin-like molecule α (RELMα), 5′-AGA TGG GCC TCC TGC CCT GCT GGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACC TGG TGA CGG GCG ACG ACG GTT-3′ (reverse); TGF-β1, 5′-CCG CAA CAA CGC CAT CTA TG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGC CCT GTA TTC CGT CTC CT-3′ (reverse); IL-17A, 5′-ACT ACC TCA ACC GTT CCA CG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAC ACC CAC CAG CAT CTT CT-3′ (reverse); IL-12/IL-23p40, 5′-TGT GGA ATG GCG TCT CTG T-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGG TCT GGT TTG ATG ATG TCC-3′ (reverse); IL-10, 5′-AAG GGT TAC TTG GGT TGC CA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCA CTC TTC ACC TGC TCC AC-3′ (reverse); IL-22, 5′-TGC TTC TCA TTG CCC TGT G-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGG ATG TTC TGG TCG TCA CC-3′ (reverse); and IL-6, 5′-TTC ACA AGT CGG AGG CTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CA GTT TGG TAG CAT CCA T-3′ (reverse).

Evaluation of cytokine production and morbidity

IL-12/IL-23p40, TGF-β, IL-17A, IFN-γ, and IL-6 levels were measured using commercially available ELISA kits (eBioscience). In some instances, production of IL-4, TNF, and IFN-γ was measured in sera by in vivo cytokine capture assay (11). Serum LPS concentration was measured using a commercially available LAL kit (Bio Whittaker, Walkersville, MD) as described previously (11). Mouse myeloperoxidase (MPO) was measured by a commercially available ELISA (Cell Sciences, Canton, MA). Nitrite was measured by Griess reaction (Promega, Madison, WI). Ileal punch biopsy specimens were cultured in RPMI 1640 plus 10% FCS for 24 h, and supernatants were stored at −80°C prior to ELISA. Determination of serum levels of aspartate transaminase was performed at the Cincinnati Veterans Administration Medical Center Clinical Pathology Laboratory (Cincinnati, OH) as described previously (11). Peritoneal exudate cells (PECs) were isolated following peritoneal lavage of WT and Arg I−/− BM chimeras at 7 wk postinfection with RPMI 1640 plus 10% FCS, allowed to adhere to plastic for 1 h, washed, trypsinized, and replated at 2.5×104/ml. Cells were left untreated or exposed to LPS (1 µg/ml) for 16 h, and supernatants were harvested and stored at −80°C prior to analysis.

Pharmacological inhibitors

For arginase inhibition, mice were provided drinking water that contained 0.2% S-(2-boronoethyl)-L-cysteine (BEC), which was synthesized and purified as described previously (12). Some mice were injected biweekly with 2 mg of the NOS-2 antagonists 1400W (Sigma-Aldrich) or NG-monomethyl-L-arginine (Sigma-Aldrich). Rat-anti-mouse IL-12/IL-23p40 (C17.8) (Wistar Institute Philadelphia, PA) or an IgG2a isotype control (GL117) was produced in Pristane-primed (Acros Organics) athymic nude mice as ascites and purified by ammonium sulfate precipitation and diethyl-amino-ethyl-cellulose column chromatography as described previously (4).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was assessed by either one-tailed Students t test (two groups) or ANOVA for multiple groups with a posthoc Bonferroni’s test to determine significance; all were performed using Prism Graph Pad software.

Results

Arg I expression is dependent on IL-4Rα expression in BM-derived cells

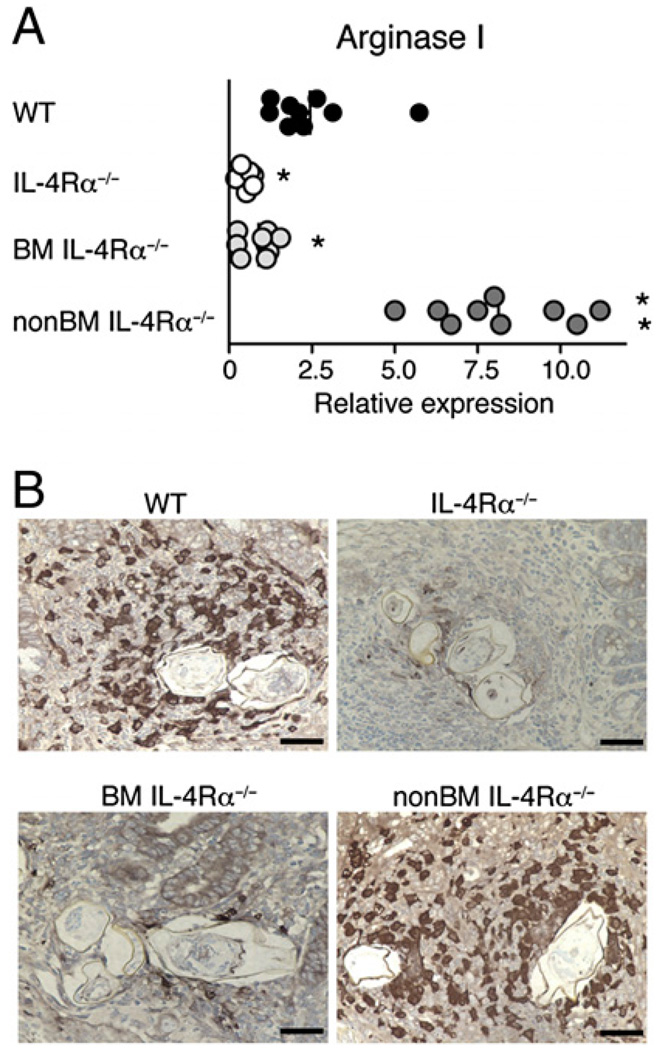

During murine schistosomiasis, the nature of L-arginine metabolism is closely linked to disease outcome. Whereas IFN-γ–driven NOS-2 is associated with CAMφs and increased mortality, IL-4/IL-13– driven Arg I production is associated with AAMφs and long-term survival (7, 10). Consistent with this, S. mansoni-infected chimeric mice that express IL-4Rα only on BM-derived cells survive better than infected mice that lack IL-4Rα on these cells (11), and intestinal Arg I mRNA is increased 8- to 9-fold in chimeras that express IL-4Rα only on BM-derived cells (non–BMIL-4Rα−/−) compared with chimeras that express IL-4Rα only on non–BM-derived cells (BM IL-4Rα−/−) (Fig. 1A). Intestinal Arg I mRNA levels are also ~3-fold higher in S. mansoni-infected non–BMIL-4Rα−/− than in infected WT mice, suggesting that increased Arg I production by IL-4/IL-13–responsive BM-derived cells may compensate for the failure of non–BM-derived cells to respond to IL-4 and IL-13. Furthermore, BM-derived IL-4Rα is required for Arg I expression by inflammatory cells that encapsulate worm ova within intestinal granulomas during acute schistosomiasis (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Arg I production in S. mansoni granulomas requires IL-4Rα expression only on BM-derived cells. A, Intestinal mRNA transcripts for Arg I were quantitated by real-time PCR 7.4 wk postinoculation in S. mansoni-infected BM chimeras that expressed IL-4Rα on all cells (WT), lacked IL-4Rα expression on all cells (IL-4Rα−/−), lacked IL-4Rα expression on BM-derived cells (BMIL-4Rα−/−), or lacked IL-4Rα expression on non–BM-derived cells (non–BMIL-4Rα−/−). Transcript levels are expressed as fold increase compared with naive WT tissue. Experiment performed three times with similar results. n = 6–8 mice/group; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 compared with WT. B, Immunohistochemical staining for Arg I was performed 7.4 wk postinfection on intestinal granulomas from WT (top left panel), IL-4Rα−/− (top right panel), BMIL-4Rα−/− (bottom left panel), and BMIL-4Rα−/− (bottom right panel) mice. Original magnification ×400. Representative photos from 150 granulomas examined per group. Positive staining indicated by dark brown color.

Arg I protects S. mansoni-infected mice from cachexia and mortality during acute infection

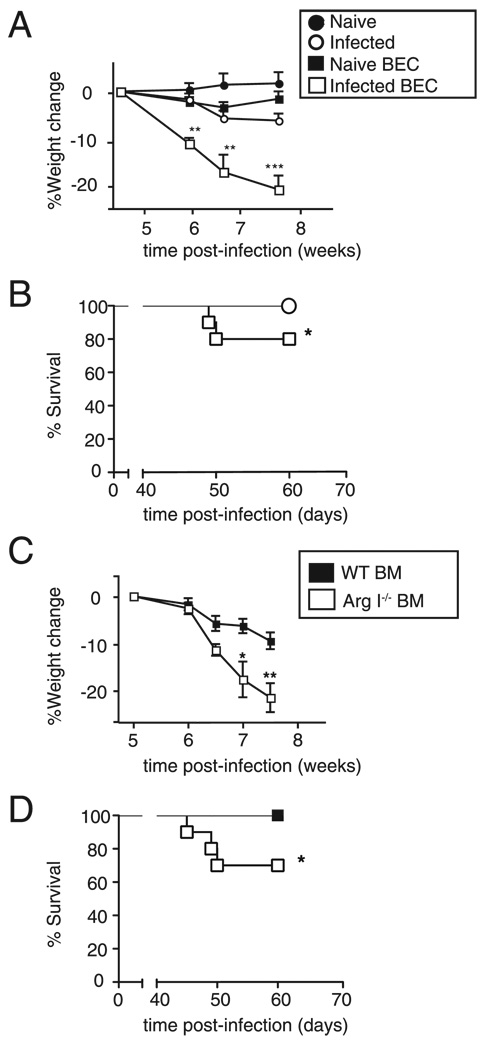

We predicted that if Arg I production by AAMφs reduces tissue injury, impairment of arginase activity should exacerbate infection-induced immunopathology caused by worm ova that lodge in host organs. Two approaches were used to test this hypothesis: 1) S. mansoni-infected WT BALB/c mice were treated with BEC, a competitive inhibitor that specifically blocks Arg I and II function (12, 13); and 2) BM chimeric mice, generated by reconstituting lethally irradiated C57BL/6 WT mice (Ly5.1+) with BM from Ly5.2+ Arg I-deficient (Arg I−/− BM) or Ly5.2+ WT (WT BM) mice, were infected with S. mansoni. Results of studies with these two models were remarkably similar and were consistent with those recently reported in Pesce et al. (9). S. mansoni-infection caused severe weight loss (Fig. 2A) and ~20–30% mortality (Fig. 2B) in mice provided with 0.2% BEC in drinking water, but these did not occur in BEC-treated uninfected mice or in infected mice that were not treated with BEC. Similarly, severe weight loss (Fig. 2C) and 30–35% mortality (Fig. 2D) developed in infected Arg I−/− BM mice but not infected WT BM mice. The monocyte/Mφ population (as defined by CD11b+ staining) was consistently >95% donor derived in both chimeric groups (data not shown). However, we noted that most worm-infected mice began to recover ~9 wk postworm inoculation, regardless of whether mice were BEC-treated or Arg I BM−/− chimeras (data not shown). This is distinct from S. mansoni-infected Mφ-specific IL-4Rα–deficient mice, which experience 100% mortality by 9 wk postinoculation (10). Thus, Arg I production appears to be an important mechanism but not the only mechanism by which myeloid cell IL-4Rα expression inhibits lethal inflammation.

FIGURE 2.

Mice treated with an arginase antagonist or chimeras lacking BM-derived Arg I develop cachexia and increased mortality during acute schistosomiasis. Weight change (A) and survival (B) of naive or S. mansoni-infected mice that were administered normal drinking water or drinking water containing BEC. Weight change (C) and survival (D) of WT and Arg I−/− BM chimeras following inoculation with 60–70 S. mansoni cercariae. Representative of three independent experiments with 8–10 mice/group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 compared with WT-infected group.

BM-derived Arg I protects against worm ova-induced damage to the intestine

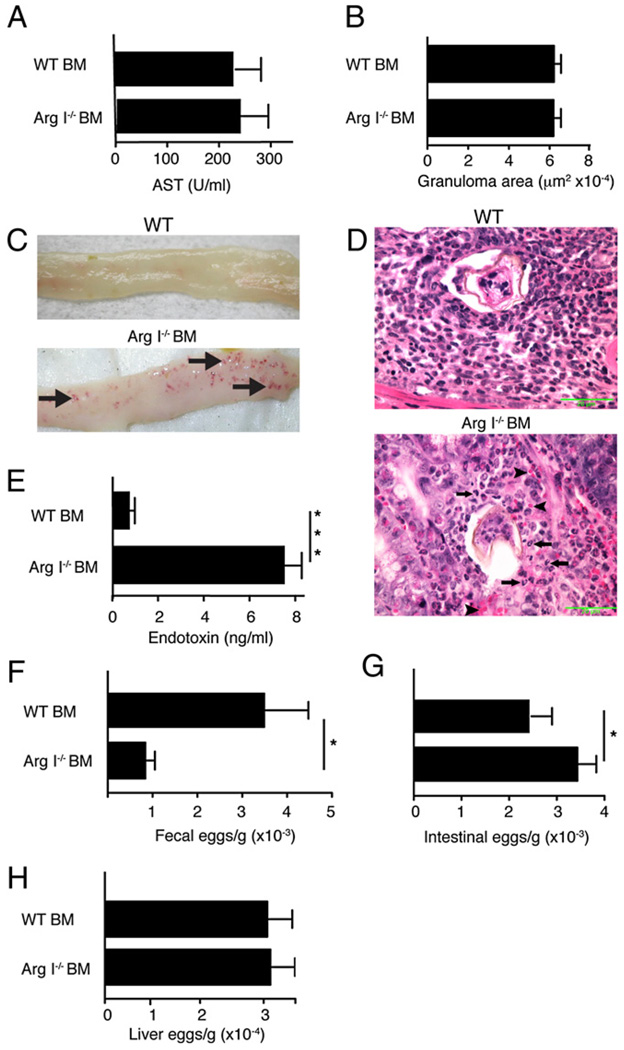

S. mansoni adult worms produce large numbers of parasite ova (size range, 60–100 µm) starting 5.5 wk postinfection, which cause granulomas to form in liver and intestine. Arg I−/− BM chimeras did not show any signs of excessive liver injury (Fig. 3A) or altered granuloma size (Fig. 3B), but these animals developed numerous hemorrhagic areas within the gut mucosa by 7.5 wk postinfection that were not observed in WT BM chimeras (Fig. 3C). These abnormalities were accompanied by neutrophil infiltration (Fig. 3D) and greatly increased serum levels of endotoxin (Fig. 3E). Arg I−/− BM chimeras had significantly fewer worm ova within the feces (Fig. 3F) but increased numbers of worm ova in the terminal ileum compared with WT controls (Fig. 3G). A remarkably similar phenotype was noted in BEC-treated WT mice analyzed between 7 and 8 wk postinfection (data not shown). In contrast, we never observed increased numbers of hepatic ova in S. mansoni-infected Arg I−/− BM chimeras (Fig. 3H) or BEC-treated WT mice (data not shown). These data suggest that the rate in which parasite ova are excreted from the bowel wall was markedly impaired in mice lacking BM-derived Arg I. Thus, Arg I deficiency preferentially exacerbated intestinal injury but only caused marginal effects on S. mansoni-induced liver pathology.

FIGURE 3.

BM Arg I deficiency causes increased tissue injury, ova accumulation, and neutrophilic inflammation in the intestine during acute schistosomiasis. Serum levels of AST (A) and liver granuloma size (B). Representative of 150 granulomas evaluated with 8–10 mice/group. C, Representative photographs of terminal ileum from S. mansoni-infected WT BM or Arg I−/− BM chimeras 7.4 wk postinoculation. Note areas of hemorrhage (arrows). D, Representative photomicrographs of intestinal granulomas in WT BM and Arg I−/− BM chimeras at 7.5 wk postworm inoculation. Arrowheads point to erythrocytes, and arrows indicate neutrophils. Fifty granulomas examined per group. Original magnification ×600. Serum endotoxin levels (E), number of parasite ova in feces (F), intestine (G), and liver (H) at 7.4 wk postinoculation. Representative of three independent experiments with 8–10 mice/group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 compared with WT-infected group. AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

Arg I-deficient chimeras produce molecules associated with CAMφ

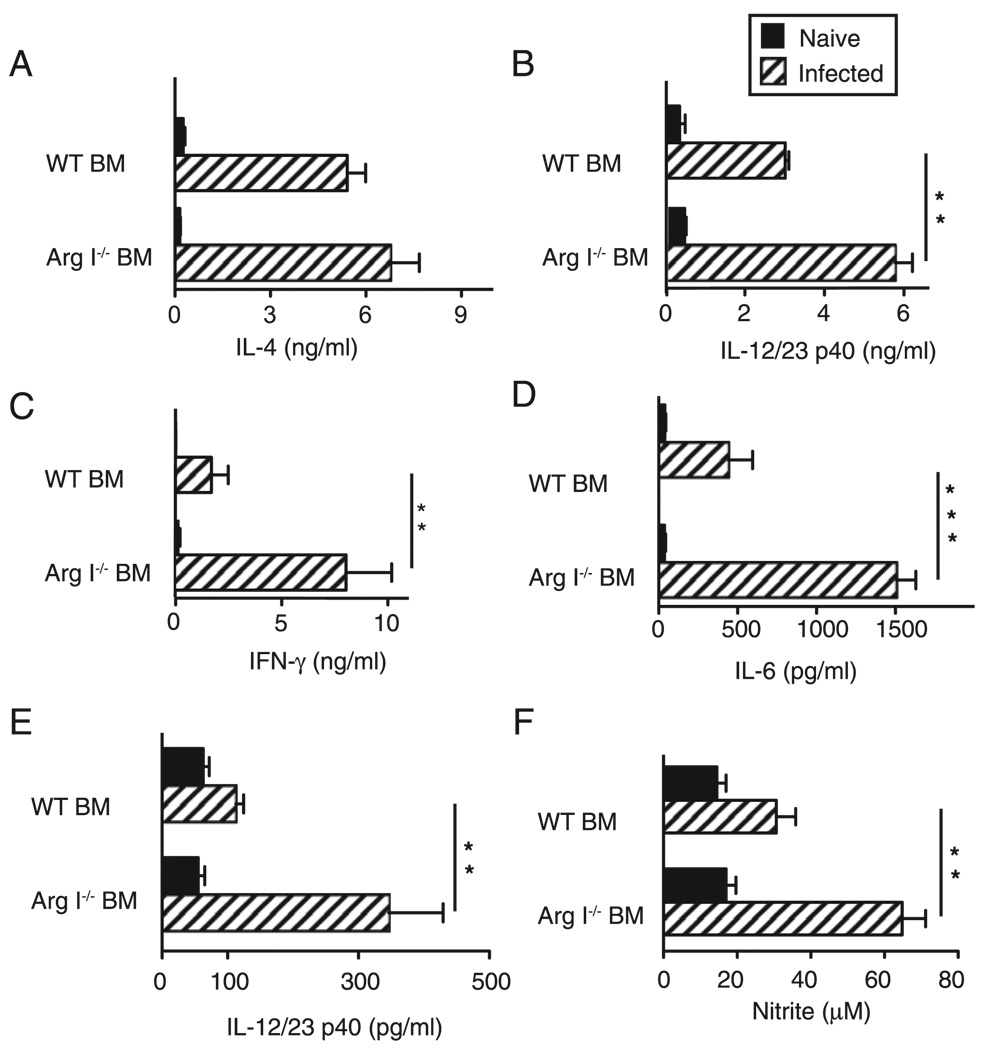

By 7.5 wk postinfection, BM Arg I deficiency did not impair IL-4 (Fig. 4A) or IL-13 (data not shown) production but resulted in a significant increase of IL-12/IL-23p40, IFN-γ and IL-6 (Fig. 4B– D), as compared with WT controls. Similar abnormalities in cytokine profile were observed in S. mansoni-infected IL-4Rα−/−, IL-4−/−, and Mφ-specific IL-4Rα−/− mice (10, 14, 15); therefore, we hypothesized that BM Arg I deficiency during S. mansoniinfection predisposes Mφs to express proinflammatory molecules associated with CAMφs. To address this issue, adherent PECs from Arg1−/− BM or WT chimeras were stimulated with LPS to mimic endotoxin exposure as worm ova pass from the small intestine into the fecal stream, a process that normally occurs during infection (16). Indeed, LPS-stimulated significantly more IL-12/IL-23p40 (Fig. 4E) and nitrite (Fig. 4F) from Arg I−/− adherent peritoneal exudates, compared with WT cells.

FIGURE 4.

Arg I-deficient BM chimeras produce elevated proinflammatory cytokines and show evidence of classical Mφ activation. Systemic production of IL-4 (A), IL-12/IL-23p40 (B), IFN-γ (C), and IL-6 (D) in WT and Arg I−/− BM chimeras analyzed 7.4 wk postinoculation. Adherent peritoneal cells from S. mansoni-infected WT BM or Arg I−/− BM chimeras were stimulated with 1 µg/ml Escherichia coli endotoxin for 24 h and supernatants analyzed for levels of IL-12/IL-23p40 (E) and nitrite (F). Representative of three independent experiments with mean ± SE, n = 8–10 mice/group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

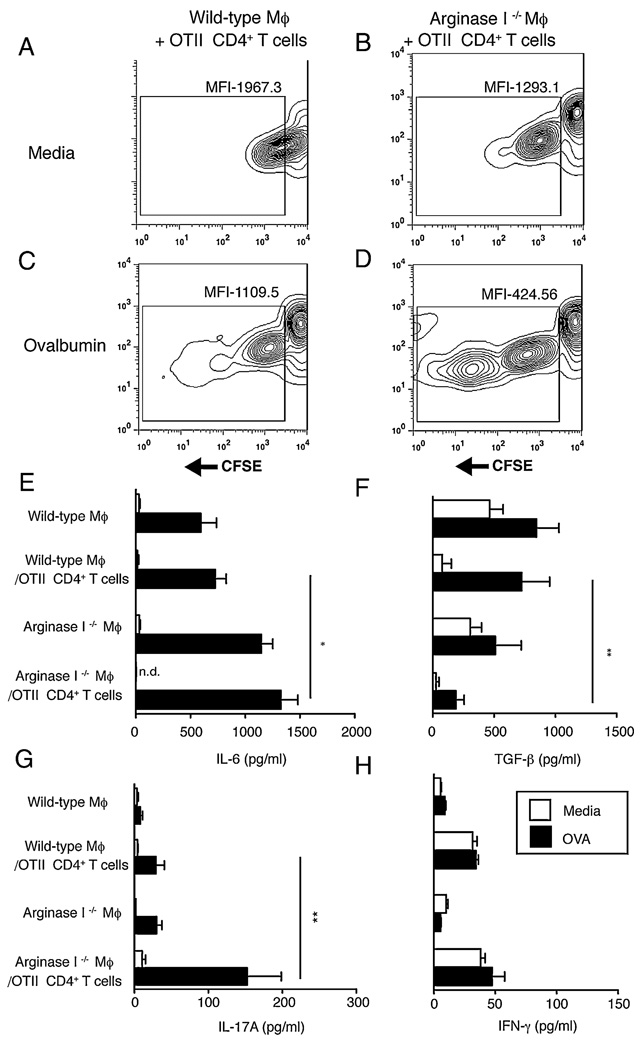

To directly assess whether Mφ-specific Arg I expression influences T cell proliferation or cytokine production, in vitro coculture experiments were performed that used WT or Arg I−/− BMMφs and CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells purified from OVA-specific TCR transgenic mice (OT-II). As expected, marginal dilution of CFSE was observed when WT Mφs were incubated with OVA-specific T cells in the absence of Ag (Fig. 5A); however, Arg I−/− Mφs stimulated a moderate amount of CFSE dilution (indicative of proliferation) (Fig. 5B). In the presence of OVA, WT Mφ-induced CFSE dilution in OT-II cells was 3-fold less than Arg I−/− Mφ (Fig. 5C, 5D). Analysis of culture supernatants revealed an inverse correlation between the production of IL-6 and TGF-β, with increased IL-6 and significantly less TGF-β produced by T cell-Arg I−/− Mφ cocultures compared with the WT Mφ-T cell cocultures (Fig. 5E, 5F). This was associated with significantly increased levels of IL-17A, but no difference between IFN-γ levels in T cell-Arg I−/− Mφ cocultures, compared with T cell-WT Mφ cocultures (Fig. 5G, 5H). Combined, this suggests that Arg I + Mφs suppress Th17 differentiation from naive Ag-specific T cells.

FIGURE 5.

Arg I-deficient macrophages drive Ag-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation and preferentially induce Th17 differentiation. Contour plots showing MFI of CFSE within OTII CD4+ T cells following coculture with (A, C) WT or (B, D) Arg I-deficient macrophages that were either (A, B) untreated or (C, D) pulsed with 50 µg/ml OVA. Analysis was performed at 96 h. From the experiment shown above, supernatants were analyzed for production of IL-6 (E), TGF-β (F), IL-17 (G), and IFN-γ (H) by ELISA. □ media alone; ■, OVA. Representative of three independent experiments with mean ± SE of triplicate wells. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

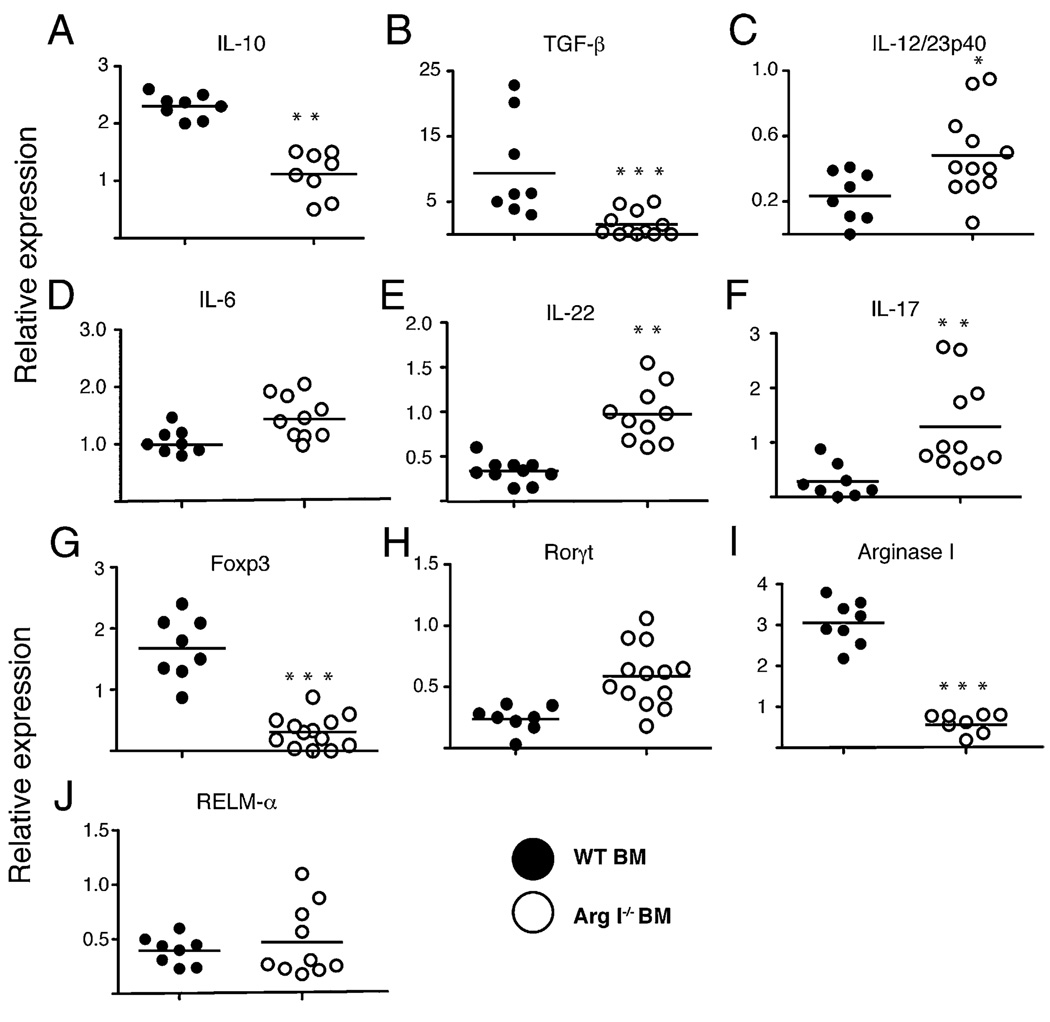

Real-time PCR was used to determine whether the lack of Arg I + Mφ resulted in a more proinflammatory microenvironment for S. mansoniova within the small intestine. Results revealed a marked decrease in the relative amounts of IL-10 and TGF-β (Fig. 6A, 6B) and a significant increase in IL-12/IL-23p40, IL-6, IL-22, and IL-17A mRNA transcripts (Fig. 6C–F) in the intestinal tissue of Arg I−/− BM chimeras, as compared with WT BM chimeras 7.5 wk after S. mansoni inoculation. This expression profile correlated with impaired Foxp3 (forkhead box P3) and elevated retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor (Rorγt) expression (Fig. 6G, 6H), suggesting an imbalance of regulatory T (Treg) and Th17 cells, respectively (17). As expected, S. mansoni-infected Arg I−/− BM chimeras express much less Arg I mRNA (Fig. 6I) but similar levels of other AAMφ-associated genes, including RELMα (FIZZ-1) (Fig. 6J), as compared with infected WT controls. Thus, lack of BM-derived Arg I (most likely in Mφs) profoundly disrupts the normal cytokine and cellular milieu of worm ova within the intestine toward a more proinflammatory environment.

FIGURE 6.

Arg I-deficient BM chimeras show decreased expression of immunosuppressive cytokines and increased Th17-associated cytokines in the intestine during acute schistosomiasis. Intestinal mRNA levels for murine IL-10 (A), TGF-β (B), IL-12/IL-23p40 (C), IL-6 (D), IL-17 (E), IL-22 (F), Foxp3 (G), Rorγt (H), ArgI (I), and RELMα (J), quantitated by real-time PCR 7.4 wk post-S. mansoni inoculation of BM chimeras. Representative of three independent experiments with mean ± SE, n = 8–10 mice/group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

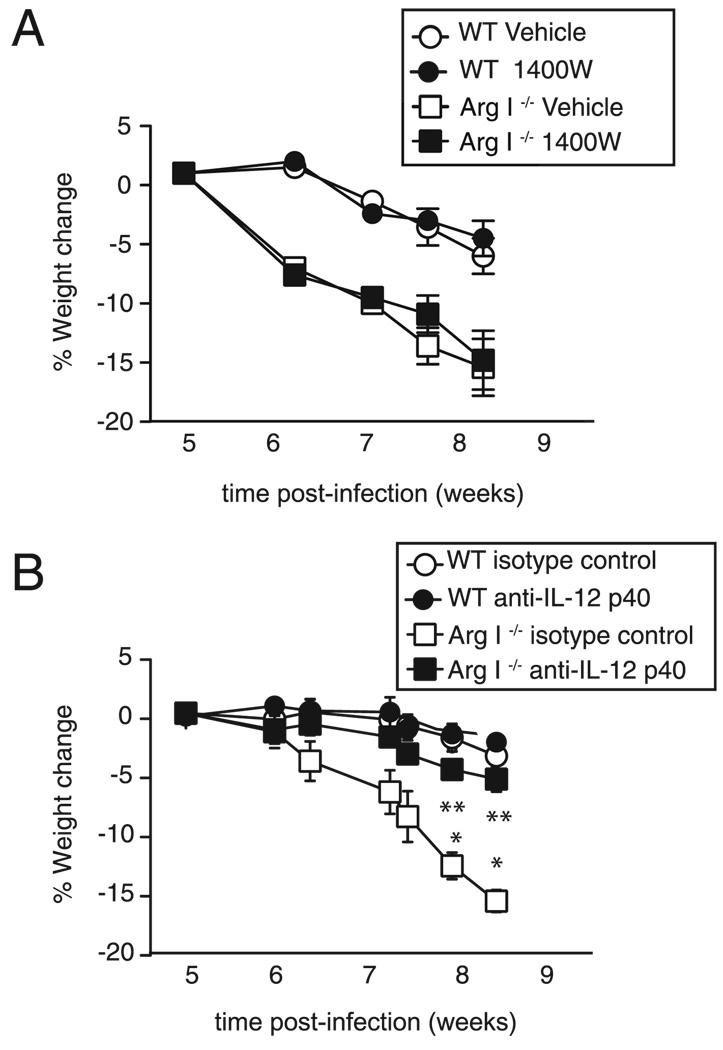

IL-12/IL-23p40 neutralization in Arg I-deficient BM chimeras abrogates cachexia and gut injury

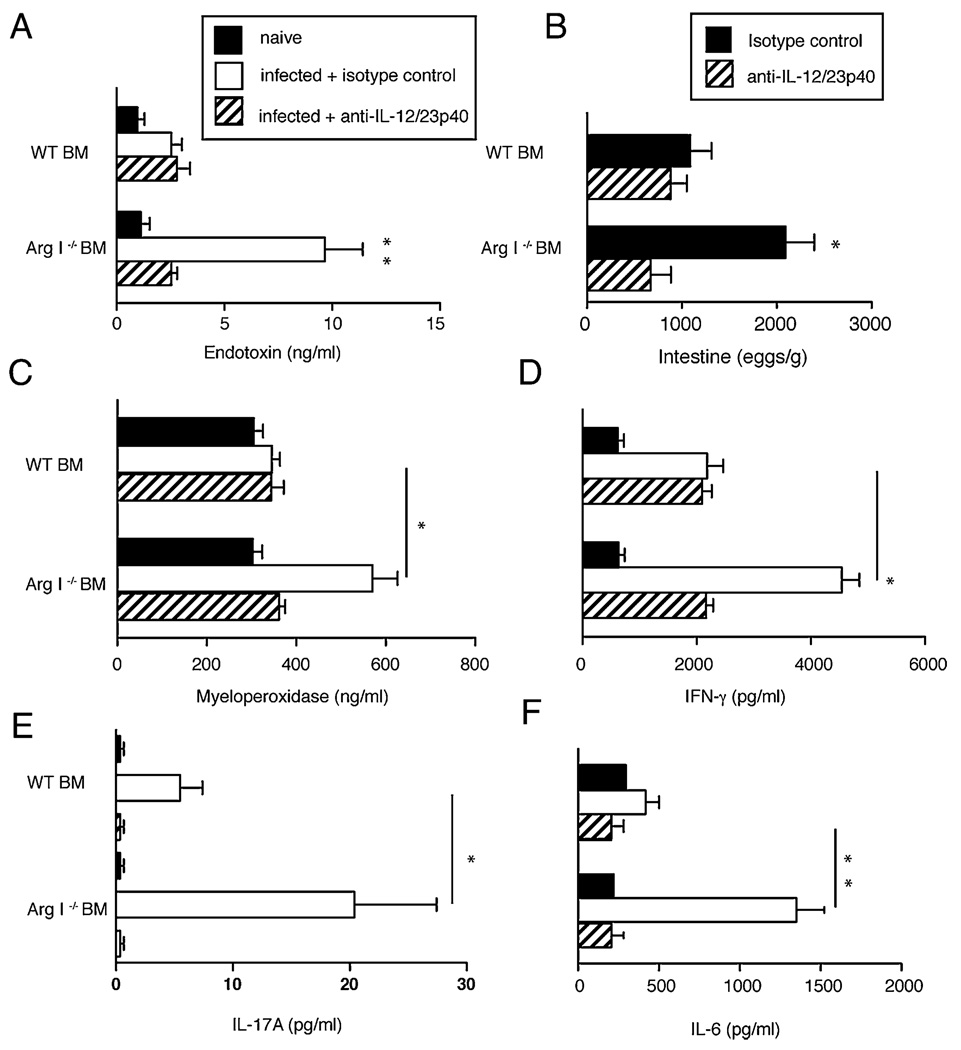

To determine whether NO and/or IL-12/IL-23p40 directly contribute to intestinal pathology in S. mansoni-infected mice, pharmacological inhibition of NOS-2 and neutralization of IL-12/IL-23p40 was performed. Treatment of Arg I−/− BM chimeras with the NOS-2–specific antagonists 1400W (Fig. 7A) or NG-monomethyl-L-arginine (data not shown) did not reverse cachexia, but treatment with anti–IL-12/IL-23p40 mAb abrogated infection-induced weight loss (Fig. 7B). Anti– IL-12/IL-23p40 mAb treatment also significantly reduced serum endotoxin levels (Fig. 8A) and the number of gut-trapped ova 8 wk after worm inoculation (Fig. 8B). Anti–IL-12/IL-23p40mAbtreatment also reduced serum levels of MPO (an indicator of neutrophil de-granulation) (Fig. 8C), IFN-γ, (Fig.8D), IL-17A (Fig. 8E),and ex vivo IL-6 production by ileal explants (Fig. 8F). Combined, this demonstrates a critical role for IL-12/IL-23p40 production in driving the neutrophil associated intestinal injury that occurs in S. mansoni-infected Arg I−/− BM chimeras.

FIGURE 7.

IL-12/IL-23p40 neutralization but not NOS-2 inhibition rescues Arg I−/− BM chimeras from cachexia. Weight change of S. mansoni-infected WT and Arg I−/− BM chimeras that were administered 2 mg biweekly injections of the NOS-2 antagonist 1400W versus saline (vehicle) (A) or 2 mg rat anti–IL-12/IL-23p40 (C17.8) versus rat IgG2a (GL117) isotype control mAb (B) starting 5 wk postworm inoculation. Representative of two independent experiments n = 8–10 mice/group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

FIGURE 8.

IL-12/IL-23p40 neutralization abrogates intestinal inflammation and injury and reduces S. mansoni intestinal egg accumulation in Arg I−/− BM chimeras. Levels of serum endotoxin (A), number of parasite ova in intestine (B), serum MPO (C), IFN-γ (D), IL-17A (E), and IL-6 (F) produced from ileal punch biopsies and serum levels of IFN-γ and IL-17A analyzed 8 wk postworm inoculation. Mean ± SE of 8–10 mice/group. Representative of two independent experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Discussion

Th2-associated cytokines (IL-4/IL-13) can promote host protection during many parasitic and inflammatory diseases through mechanisms that are incompletely understood. We have previously demonstrated that myeloid cell-specific IL-4Rα expression was critical for induction of AAMφs, host survival, and suppression of multiorgan inflammation during murine schistosomiasis (10, 11). In this paper, we demonstrate that BM-derived IL-4Rα expression is required for Arg I production at the nidus of inflammation caused by S. mansoni ova within the intestine. Mφ-derived Arg I suppresses Ag-specific T cell proliferation and Th17 differentiation in vitro, and Arg I neutralization during S. mansoni infection reduces Treg-associated cytokine production, increases Th1- and Th17- associated intestinal inflammation, and leads to 20–40% mortality. Arg I−/− BM chimeras are rescued via neutralization of IL-12/23p40 (essential component of IL-12 and IL-23), which suggests that CAMφs are largely responsible for this severe inflammatory disease phenotype (18). Thus, IL-4/IL-13 production suppresses pathogenesis driven by CAMφs through the antagonistic functions of Arg I; a conclusion that is remarkably concordant with demonstration that intracellular pathogens induce Arg I in Mφs as an immune evasion strategy that dampens CAMφ effector function (8).

AAMφ-derived Arg I can promote expulsion of gastrointestinal helminths via promoting smooth muscle contraction or decreasing worm viability (19, 20). However, host protection during schistosomiasis is achieved by suppression of inflammation directed against the highly immunogenic worm ova, not by elimination of adult worms (16). Indeed, death from S. mansoni infection is driven by granulomatous pathology that, if left unchecked, causes extensive collateral damage to liver and intestinal tissues (21). There is extensive evidence from infected humans and mice that demonstrates Th2 differentiation is host protective during schistosomiasis (13, 22). In contrast, inflammation characterized by Th1 and/or Th17 responses and neutrophil accumulation strongly correlates with severe hepatosplenic disease marked by cachexia and death (23). Th2 responses generated in patients with a milder form of intestinal schistosomiasis are characterized by fecal occult blood, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, which can persist for >20 y but is rarely fatal (3). Our data in the mouse model support a hypothesis that AAMφ-derived Arg I drives a critical immunoregulatory network that limits worm ova-driven inflammation within the gut mucosa through antagonizing Th1- and Th17-associated immunopathology.

S.mansoni adult worm pairs live within the mesenteric veins of the mammalian host. Although the large majority of worm ova are carried via portal blood flow into the liver, a smaller percentage travel in the opposite direction (against blood flow) into the small- and large-bowel tissue for excretion in the feces (3, 16). Thus, S. mansoni eggs that lodge within the liver are at a “dead end,” whereas S. mansoni eggs within the intestine tissue are “en route” to the external environment. Although each worm ova can be 60–100 µm in diameter, infection of most immunocompetent mouse strains does not cause any obvious sign of gut injury. However, mice lacking IL-4–responsive Mφs develop marked intestinal hemorrhage, endotoxemia, and ~100% mortality by 9 wk postinfection (10, 14, 15). Demonstrating that BM-derived Arg I also protects against intestinal hemorrhage and neutrophilic inflammation is consistent with an essential role for AAMφs, inasmuch as IL-4Rα expression in BM-derived cells was essential for Arg I expression. Interestingly, Arg I−/− chimeras harbored significantly greater numbers of worm ova within the bowel wall, but fewer excreted ova at 7.5 wk postinfection (Fig. 3). Anthony et al. (20) also described an IL-4R+Mφ population within the mucosa of the small intestine that killed Heligmosomoides polygyrus larvae through a mechanism dependent on arginase activity. Taken together, this indicates that Mφ-derived Arg I confers host protection through direct effects on the parasite or indirect effects that modulate immune responses generated by the host.

Arg I limits intestinal inflammation directed against worm ova lodged in the intestine by promoting anti-inflammatory cytokine production and inhibiting proinflammatory cytokine production. Using an OVA transgenic TCR system, we show that coculture of Arg I-deficient Mφs with naive CD4+ T cells caused significantly greater T cell proliferation compared with WT Mφs. More importantly, cultures that contained Arg I-deficient Mφs produced significantly more IL-6 and IL-17 and significantly less TGF-β compared with cultures containing naive CD4+ T cells and WT Mφs. The ratio of IL-6 to TGF-β is a critical determinant of Th17 versus Foxp3+ Treg induction (24, 25), and high levels of TGF-β directly suppress Th17 differentiation (17). Consistent with this, S. mansoni-infected Arg I−/− BM chimeras produce significantly more intestinal mRNA transcripts for Rorγt, IL-17, and IL-22 and significantly less Foxp3, IL-10, and TGF-β compared with infected WT BM chimeras. This is also consistent with our recent demonstration that the immunosuppressive cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β redundantly suppress lethality associated with IL-17 production and neutrophil expansion during acute schistosomiasis (4).

In contrast to the profound effects of Arg I deficiency on intestinal inflammation, we find no evidence for increased liver injury or granulomasize in the Arg I−/− chimeras during acute schistosomiasis. This contrasts with previous studies performed with S. mansoni-infected mice that have Mφ/neutrophil-specific IL-4Rα deficiency because these mice fail to upregulate Arg I but also develop increased liver damage and larger granulomas (10). The mechanistic basis for these differences may be related to the production of other immunoregulatory molecules by AAMφs. RELMα, an IL-4–induced, AAMφ-produced molecule that suppresses S. mansoni ova-induced lung inflammation (26), was induced in Arg I−/− chimeras at levels equivalent to WT chimeras.

As our study was being completed, Pesce et al. (9) reported that mice lacking Mφ-derived Arg I suffer increased mortality during chronic schistosomiasis because of increased liver fibrosis, exacerbated liver granulomatous pathology, increased hepatic CD4+ Th2 cells, and impaired T cell suppression by AAMφ. In their study, Mφ/neutrophil-specific Arg I-deficient mice began to die 8–9 wk postinfection, and hemorrhagic intestinal pathology was noted at autopsy (9). In fact, there were increased percentages of Th1 and Th17 cells isolated from affected organs of Arg I-deficient mutants, but mortality was attributed to excessive Th2-driven fibrosis and other complications that developed beyond 12 wk of infection (9). Despite these differences in interpretation, together both studies support the conclusion that Arg I is a critical suppressor of T cell-associated inflammation during S. mansoni infection.

Mechanistically, Arg I expression could suppress inflammation via inhibition of Mφ and/or dendritic cell production of the p40 component of IL-12 and IL-23, which stimulates Th1 and Th17 responses, respectively (23, 27). Consistent with this hypothesis, adherent PECs from S. mansoni-infected Arg I−/− BM chimeras release significantly greater amounts of IL-12/IL-23p40 than PECs from infected WT chimeras. Strikingly, IL-12/IL-23p40 neutralization reverses nearly all of the markers of disease exacerbation in Arg I−/− chimeras such as increased IL-6, IFN-γ, and IL-17 production; neutrophil degranulation; endotoxemia; numbers of worm ova lodged in the ileum; and infection-induced weight loss. This demonstrates that IL-12/23p40 production is largely responsible for severe disease in the absence of Arg I. Production of IL-12/IL-23p40 is induced by treatment of alternatively activated human monocytes with an arginase antagonist (28), and IL-12/IL-23p40 promotes severe schistosomiasis in mouse strains that produce elevated IL-17 in response to worm ova (29).

Demonstrating that anti–IL-12/IL-23p40 mAb treatment suppresses both serum LPS levels and intestinal inflammation suggests that excessive production of IL-12 and IL-23, rather than increased serum LPS, is the proximal event in S. mansoni-infected Arg I-deficient mice. Consistent with this, Gobert et al. (30) demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of arginase activity increased proinflammatory cytokine production and exacerbated colitis induced by Citrobacter rodentium, and it was also shown that neutralization of IL-12/IL-23p40 reduces the severity of murine arthritis (31). Therefore, our findings support the view that Arg I production from AAMφs suppress IL-12/23–driven inflammation, which may promote disruption of the mucosal barrier and leakage of intestinal bacteria and/or LPS into the blood.

Taken together, our studies of Arg I deficiency during acute schistosomiasis and the studies of Pesce et al. Arg I about deficiency during chronic schistosomiasis suggest a scenario that begins with the entry of S. mansoni ova into host organ tissues that drives a Th2 response (32). IL-4 and IL-13 then stimulate AAMφ differentiation and Arg I production, which in turn promotes TGF-β secretion but suppresses production of IL-6, IL-12, and IL-23. This reduces Th1 and Th17 differentiation and increases the Treg response that promotes increased IL-10 and TGF-β. These later cytokines limit intestinal neutrophilic inflammation caused by the passage of worm ova through host intestinal tissue and may promote tissue repair as worm ova are passed out of the intestine and into the fecal stream throughout the course of disease. Increased IL-4 and IL-13 production, however, has a price: it promotes development of hepatic cirrhosis that causes morbidity and death during the chronic phase of schistosomiasis.

Finally, it is worth pointing out that this scenario is a notable example of convergent evolution, inasmuch as it benefits the host by preventing life-threatening intestinal inflammation during the acute phase of S. mansoni infection but also benefits the parasite by promoting long-term dissemination of worm ova from the infected host. This strong selective advantage for both parasite and host may account for the persistence of Th2 responses despite driving fibrotic disease during chronic schistosomiasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Steve Finan, Jeff Bailey, and Kathryn Niese for expert technical assistance.

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and National Institutes of Health Grant RO1GM083204.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- AAMφ

alternatively activated macrophage

- Arg I

arginase I

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- BEC

S-(2-boronoethyl)-L-cysteine

- BM

bone marrow

- CAMφ

classically activated Mφ

- IL-4Rα

IL-4Rα–chain

- Mφ

macrophage

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- NOS-2

NO synthase-2

- PEC

peritoneal exudate cell

- RELMα

resistin-like molecule α

- Treg

regulatory T cell

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Urban JF, Jr, Noben-Trauth N, Schopf L, Madden KB, Finkelman FD. Cutting edge: IL-4 receptor expression by non-bone marrow-derived cells is required to expel gastrointestinal nematode parasites. J. Immunol. 2001;167:6078–6081. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chitsulo L, Loverde P, Engels D. Schistosomiasis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:12–13. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L. Human schistosemiasis. Lancet. 2006;368:1106–1118. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herbert DR, Orekov T, Perkins C, Finkelman FD. IL-10 and TGF-β redundantly protect against severe liver injury and mortality during acute schistosomiasis. J. Immunol. 2008;181:7214–7220. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.La Flamme AC, Patton EA, Bauman B, Pearce EJ. IL-4 plays a crucial role in regulating oxidative damage in the liver during schistosomiasis. J. Immunol. 2001;166:1903–1911. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wynn TA, Thompson RW, Cheever AW, Mentink-Kane MM. Immunopathogenesis of schistosomiasis. Immunol. Rev. 2004;201:156–167. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hesse M, Modolell M, La Flamme AC, Schito M, Fuentes JM, Cheever AW, Pearce EJ, Wynn TA. Differential regulation of nitric oxide synthase-2 and arginase-1 by type 1/type 2 cytokines in vivo: granulomatous pathology is shaped by the pattern of L-arginine metabolism. J. Immunol. 2001;167:6533–6544. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Kasmi KC, Qualls JE, Pesce JT, Smith AM, Thompson RW, Henao-Tamayo M, Basaraba RJ, König T, Schleicher U, Koo MS, et al. Toll-like receptor-induced arginase 1 in macrophages thwarts effective immunity against intracellular pathogens. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:1399–1406. doi: 10.1038/ni.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pesce JT, Ramalingam TR, Mentink-Kane MM, Wilson MS, El Kasmi KC, Smith AM, Thompson RW, Cheever AW, Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Arginase-1–expressing macrophages suppress Th2 cytokine-driven inflammation and fibrosis. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000371. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herbert DR, Hölscher C, Mohrs M, Arendse B, Schwegmann A, Radwanska M, Leeto M, Kirsch R, Hall P, Mossmann H, et al. Alternative macrophage activation is essential for survival during schistosomiasis and downmodulates T helper 1 responses and immunopathology. Immunity. 2004;20:623–635. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herbert DR, Orekov T, Perkins C, Rothenberg ME, Finkelman FD. IL-4Rα expression by bone marrow-derived cells is necessary and sufficient for host protection against acute schistosomiasis. J. Immunol. 2008;180:4948–4955. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim NN, Cox JD, Baggio RF, Emig FA, Mistry SK, Harper SL, Speicher DW, Morris SM, Jr, Ash DE, Traish A, Christianson DW. Probing erectile function: S-(2-boronoethyl)-L-cysteine binds to arginase as a transition state analogue and enhances smooth muscle relaxation in human penile corpus cavernosum. Biochemistry. 2001;40:2678–2688. doi: 10.1021/bi002317h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cama E, Colleluori DM, Emig FA, Shin H, Kim SW, Kim NN, Traish AM, Ash DE, Christianson DW. Human arginase II: crystal structure and physiological role in male and female sexual arousal. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8445–8451. doi: 10.1021/bi034340j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fallon PG, Richardson EJ, McKenzie GJ, McKenzie AN. Schistosome infection of transgenic mice defines distinct and contrasting pathogenic roles for IL-4 and IL-13: IL-13 is a profibrotic agent. J. Immunol. 2000;164:2585–2591. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunet LR, Finkelman FD, Cheever AW, Kopf MA, Pearce EJ. IL-4 protects against TNF-α–mediated cachexia and death during acute schistosomiasis. J. Immunol. 1997;159:777–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearce EJ, MacDonald AS. The immunobiology of schistosomiasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou L, Lopes JE, Chong MM, Ivanov II, Min R, Victora GD, Shen Y, Du J, Rubtsov YP, Rudensky AY, et al. TGF-β–induced Foxp3 inhibits T (H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORγt function. Nature. 2008;453:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature06878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mosser DM, Zhang X. Activation of murine macrophages. Chapter 14: Unit 14.2. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2008 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1402s83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao A, Urban JF, Jr, Anthony RM, Sun R, Stiltz J, van Rooijen N, Wynn TA, Gause WC, Shea-Donohue T. Th2 cytokine-induced alterations in intestinal smooth muscle function depend on alternatively activated macrophages. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:217–225. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.077. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anthony RM, Urban JF, Jr, Alem F, Hamed HA, Rozo CT, Boucher JL, Van Rooijen N, Gause WC. Memory T(H)2 cells induce alternatively activated macrophages to mediate protection against nematode parasites. Nat. Med. 2006;12:955–960. doi: 10.1038/nm1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffmann KF, Cheever AW, Wynn TA. IL-10 and the dangers of immune polarization: excessive type 1 and type 2 cytokine responses induce distinct forms of lethal immunopathology in murine schistosomiasis. J. Immunol. 2000;164:6406–6416. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patton EA, La Flamme AC, Pedras-Vasoncelos JA, Pearce EJ. Central role for interleukin-4 in regulating nitric oxide-mediated inhibition of T-cell proliferation and γ interferon production in schistosomiasis. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:177–184. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.1.177-184.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rutitzky LI, Stadecker MJ. CD4 T cells producing pro-inflammatory interleukin-17 mediate high pathology in schistosomiasis. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2006;101 Suppl. 1:327–330. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762006000900052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou L, Ivanov II, Spolski R, Min R, Shenderov K, Egawa T, Levy DE, Leonard WJ, Littman DR. IL-6 programs T(H)-17 cell differentiation by promoting sequential engagement of the IL-21 and IL-23 pathways. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:967–974. doi: 10.1038/ni1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou L, Chong MM, Littman DR. Plasticity of CD4+ T cell lineage differentiation. Immunity. 2009;30:646–655. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nair MG, Du Y, Perrigoue JG, Zaph C, Taylor JJ, Goldschmidt M, Swain GP, Yancopoulos GD, Valenzuela DM, Murphy A, et al. Alter-natively activated macrophage-derived RELM-α is a negative regulator of type 2 inflammation in the lung. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:937–952. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, Cua DJ, Littman DR. The orphan nuclear receptor RORγt directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Babu S, Kumaraswami V, Nutman TB. Alternatively activated and immunoregulatory monocytes in human filarial infections. J. Infect. Dis. 2009;199:1827–1837. doi: 10.1086/599090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rutitzky LI, Lopes da Rosa JR, Stadecker MJ. Severe CD4 T cell-mediated immunopathology in murine schistosomiasis is dependent on IL-12p40 and correlates with high levels of IL-17. J. Immunol. 2005;175:3920–3926. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gobertx AP, Cheng Y, Akhtar M, Mersey BD, Blumberg DR, Cross RK, Chaturvedi R, Drachenberg CB, Boucher JL, Hacker A, et al. Protective role of arginase in a mouse model of colitis. J. Immunol. 2004;173:2109–2117. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi N, de Jager VC, Glück A, Letzkus M, Hartmann N, Staedtler F, Ribeiro-Dias F, Heuvelmans-Jacobs M, van den Berg WB, Joosten LA. The molecular signature of oxidative metabolism and the mode of macrophage activation determine the shift from acute to chronic disease in experimental arthritis: critical role of interleukin-12p40. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3471–3484. doi: 10.1002/art.23956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearce EJ, Kane CM, Sun J, Taylor JJ, McKee AS, Cervi L. Th2 response polarization during infection with the helminth parasite Schistosoma mansoni. Immunol. Rev. 2004;201:117–126. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]