Abstract

Objective

To retrospectively evaluate the 12-month effectiveness of the Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting stent (ZES) in diabetic versus non-diabetic patients enrolled in the E-Five Registry.

Design and Setting

The E-Five Registry is a prospective, multicentre registry of 8314 patients presenting with symptomatic coronary artery disease treated with the Endeavor (ZES). Patients were treated at 188 centres located in 37 countries across Europe, Latin America and Asia Pacific.

Patients

There were 2721 (32.7%) patients with diabetes (DM) and among these patients 682 were insulin-treated (ITDM) and 2039 were non-insulin-treated diabetic patients (NITDM).

Interventions

All enrolled patients received an Endeavor ZES and were followed for 12 months.

Main outcome measurements

The primary outcome measure was major adverse cardiac event (MACE) at 12 months. Secondary endpoints included target lesion revascularisation (TLR), target vessel revascularisation (TVR), target vessel failure (TVF) and stent thrombosis.

Results

Compared with non-DM patients, DM patients had higher rates of MACE (9.7% vs 6.4%, p<0.001), TLR (5.3% vs 4.0%, p=0.028) and Academic Research Consortium (ARC) definite and probable stent thrombosis (1.5% vs 0.9%, p=0.041). Compared with non-DM patients, ITDM patients had higher rates of MACE (12.6% vs 6.4%, p<0.001). ITDM patients had higher rates of death (6.7% vs 1.7%, p<0.001), cardiac death (4.5% vs 1.2%, p<0.001) and TLR (6.5% vs 4.0%, p=0.011) than non-DM patients.

Conclusions

The Endeavor ZES performed well in DM patients; however, DM patients experienced higher rates of adverse clinical events compared with non-DM patients.

Trial Reg No

Clinical trial registration information: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NTC00623441

Keywords: Endeavor, zotarolimus, global registry, diabetes, major adverse cardiac event, drug-eluting stent, coronary stenting, coronary artery disease (CAD)

Introduction

Patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) are at increased risk of restenosis and other adverse cardiac events following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stent implantation when compared with non-diabetic (non-DM) subjects. Drug-eluting stents, when used in randomised controlled trials, have improved the outcomes of PCI with stent implantation.1 That insulin therapy is associated with adverse outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease treated with PCI remains controversial. Randomised controlled trials have not included sufficient numbers of patients to fully answer this question. Registry data have suggested that patients with insulin-treated diabetes mellitus (ITDM) have worse outcomes than non-insulin treated (NITDM) diabetic patients.2 The Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting stent (ZES) (Medtronic CardioVascular, Santa Rosa, California, USA) is a relatively recent addition to the drug-eluting stent armamentarium and has been shown to be effective for the treatment of single, de novo coronary lesions in randomised, controlled trials that included DM patients.3–5 However, the Endeavor ZES's performance in DM patients in a ‘real-world’ population with coronary artery disease remains largely unknown.

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of the Endeavor ZES in DM patients in a ‘real-world’ setting, we analysed the clinical outcomes of ITDM and NITDM patients enrolled in the E-Five Registry.6 The E-Five Registry was a prospective, non-randomised, multicentre, global registry in which more than 8000 adult patients with coronary artery disease who underwent single-vessel or multi-vessel Endeavor ZES implantation were enrolled without any specific anatomical or clinical exclusion criteria. Twelve-month clinical safety and performance outcomes for the E-Five Registry patients were recently reported.7 Here we report the results of the E-Five diabetic subgroup analysis, which compared the 12-month clinical outcomes between non-DM and DM patients, and NITDM and ITDM patients.

Methods

Study design, population and objectives

The design and management of the E-Five Registry has been described in detail elsewhere.6 Briefly, the registry enrolled 8314 adult patients with coronary artery stenosis who underwent single-vessel or multivessel PCI with the Endeavor ZES at one of 188 hospitals in 37 countries including 24 in Europe, three in South America, eight in Asia and Australia, New Zealand, Mexico and India. There were no specific anatomical or clinical exclusion criteria, and the presence of multiple coronary artery stenoses in multiple vessels did not preclude the enrolment of patients in the registry. The population of the E-Five Registry was thus intended to include acute presentations and complex patient and lesion subgroups.

For the E-Five diabetes subgroup study, 12-month event data were compared retrospectively between non-DM and DM patients and between NITDM and ITDM patients. DM was the accepted diagnosis if the patient presented with a prior diagnosis and was taking diabetic-specific therapy; no specific laboratory confirmatory test was required. The adjudicated event data included major adverse cardiac events (MACE), target lesion revascularisation (TLR), target vessel revascularisation (TVR), target vessel failure (TVF) and stent thrombosis. MACE was defined as the composite endpoint of death, myocardial infarction (MI; Q wave and non-Q wave), emergency cardiac bypass surgery or TLR. Non-Q wave MI was defined as an elevated creatine kinase (CK) of at least twice the upper limit of normal with the presence of elevated creatine kinase MB isoenzyme (CK-MB) and in the absence of new pathological Q waves. TLR was defined as any percutaneous intervention or bypass surgery performed on the index target lesion at any time after the index procedure. TVR was defined as any percutaneous intervention or bypass surgery performed on the index target vessel at any time after the index procedure. TVF was defined as TVR, cardiac death or MI. Stent thrombosis was defined as a thrombotic occlusion or stenosis of the stented target lesion, or in the absence of angiogram, an ST-segment elevation MI in the territory of the index vessel. In addition to the protocol definition, the Academic Research Consortium (ARC) definitions of stent thrombosis were applied to the dataset retrospectively, then analysed and reported.8 There was no mandatory angiographic follow-up in the E-Five Registry protocol.

The E-Five Registry was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and local ethics committees approved the study protocol. Written, informed consent was obtained from every patient. The authors had full access to data and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

Data collection and management

The registry's clinical data were prospectively collected by dedicated research nurses on a web-based case report form, and for 10% of the patients, the data were verified by study monitors at hospital visits. Patient follow-up data were obtained during a scheduled clinic visit whenever possible or alternatively by phone contact. All events related to endpoints were reported to an independent clinical endpoints committee, which consisted of cardiologists not taking part in the study.

Device description

The Endeavor ZES used to treat patients in the E-Five Registry is composed of three different components: (1) the low-profile, thin-strut, cobalt-alloy Driver stent (Medtronic CardioVascular, Santa Rosa, California, USA); (2) a proprietary biomimetic phosphorylcholine polymer; and (3) zotarolimus, an antiproliferative drug that is a synthetic analogue of sirolimus and has a similar mechanism of action. The Endeavor ZES carries a dose concentration of 10 μg zotarolimus/mm stent length. Experimental evaluation of the elution profile of zotarolimus has revealed that approximately 95% of the active drug is eluted from the stent within 15 days of implantation.9 For the E-Five Registry, the Endeavor ZES was available in diameters of 2.25–4.0 mm and in lengths of 8–30 mm.

Statistical methods

The primary analytical population consisted of all enrolled patients in whom an Endeavor stent was attempted and/or implanted. The clinical outcomes of DM patient (ITDM and NITDM) and non-DM patient subgroups were evaluated.

The baseline demographic and lesion characteristics, procedural characteristics, and the clinical outcomes were assessed and presented here based on the presence and the nature of treatment of DM. Categorical variables were reported using percentages and counts, and continuous variables by the means and standard deviations. The times to MACE and stent thrombosis were summarised and displayed using cumulative incidence curves by Kaplan-Meier methods. Subgroups were compared for baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes. p Values were calculated using a two-sample t test for continuous variables or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. In addition, clinical outcomes were compared between subgroups using adjusted p values, calculated using logistic regression adjusted for propensity scores. Propensity scores were calculated using the following baseline variables: age, sex, prior MI, prior percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery, acute MI (<72 hours), hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, smoking, left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) (vs non-LAD), B2C (vs AB1), lesion length (≥27 mm vs <27 mm) and reference vessel diameter (>3.5 mm vs ≤3.5 mm).

Results

Patient characteristics

Baseline demographic, clinical and procedural characteristics of all 8314 registry patients are listed in table 1. Of the 2721 (32.7%) registry patients with diabetes, 682 (25.1%) had ITDM. Overall, DM patients compared with non-DM patients tended to be older, female and non-smokers with a higher incidence of hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, unstable angina and moderate–to-severe renal impairment. At the time of the baseline procedure, the number of lesions treated was higher in DM patients than in non-DM patients.

Table 1.

Baseline patient and lesion characteristics for all 8314 patients enrolled in the E-Five Registry stratified by diabetes status

| Characteristic | Non-DM | DM | p Value | NITDM | ITDM | p Value |

| (n=5593) | (n=2721) | (n=2039) | (n=682) | |||

| (n=6884 lesions) | (n=3455 lesions) | (n=2595 lesions) | (n=857 lesions) | |||

| Age (years) mean±SD |

62.31±11.34 (5593/5593) |

65.32±10.16 (2721/2721) |

<0.001 | 64.90±10.23 (2039/2039) |

66.57±9.85 (682/682) |

<0.001 |

| Female (%) | 19.8 (1106/5593) |

30.7 (834/2721) |

<0.001 | 28.2 (576/2039) |

37.8 (258/682) |

<0.001 |

| Unstable angina (%) | 33.1 (1851/5593) |

35.6 (969/2721) |

0.023 | 35.6 (725/2039) |

35.8 (244/682) |

0.926 |

| Prior MI (%) | 31.8 (1776/5593) |

33.0 (897/2721) |

0.271 | 32.0 (653/2039) |

35.8 (244/682) |

0.074 |

| AMI ≤72 hours* (%) | 14.8 (829/5593) |

11.9 (324/2721) |

<0.001 | 12.1 (247/2039) |

11.3 (77/682) |

0.586 |

| AMI <6 hours*† (%) | 5.2 (145/2810) |

3.1 (39/1263) |

0.003 | 2.8 (27/954) |

3.9 (12/309) |

0.347 |

| AMI 6–24 hours*† (%) | 5.3 (149/2810) |

4.4 (56/1263) |

0.278 | 4.1 (39/954) |

5.5 (17/309) |

0.339 |

| Prior PCI (%) | 25.5 (1426/5593) |

25.0 (680/2721) |

0.629 | 23.5 (480/2039) |

29.3 (200/682) |

0.003 |

| Prior CABG (%) | 7.3 (407/5593) |

8.1 (220/2721) |

0.199 | 7.2 (147/2039) |

10.7 (73/682) |

0.005 |

| Current smoker (%) | 25.4 (1419/5593) |

17.0 (463/2721) |

<0.001 | 18.0 (368/2039) |

13.9 (95/682) |

0.013 |

| Hypertension (%) | 63.7 (3564/5593) |

78.6 (2140/2721) |

<0.001 | 77.5 (1580/2039) |

82.1 (560/682) |

0.011 |

| Treated hyperlipidaemia (now or in past) (%) | 60.8 (3400/5593) |

67.7 (1843/2721) |

<0.001 | 67.7% (1380/2039) |

67.9% (463/682) |

0.962 |

| Moderate renal impairment (creatinine 140–220 mol/l)*† (%) | 3.6 (164/4540) |

7.0 (153/2180) |

<0.001 | 5.5 (91/1643) |

11.5 (62/537) |

<0.001 |

| Severe renal impairment (creatinine >220 mol/l)*† (%) | 1.0 (47/4540) |

3.3 (73/2180) |

<0.001 | 2.3 (38/1643) |

6.5 (35/537) |

<0.001 |

| B2/C lesions (%) | 60.0 (4128/6884) |

60.8 (2101/3455) |

0.418 | 61.0 (1585/2598) |

60.2 (516/857) |

0.678 |

| Lesion length (mm) | 18.49±10.54 (6881) |

18.55±10.74 (3451) |

0.790 | 18.57±10.84 (2595) |

18.49±10.46 (857) |

0.849 |

| Number of stents implanted | 1.19±0.48 (6884) |

1.18±0.47 (3455) |

0.242 | 1.17±0.46 (2598) |

1.19±0.50 (857) |

0.340 |

| Total stent length (mm) | 23.49±12.21 (6884) |

23.45±12.21 (3455) |

0.902 | 23.51±12.41 (2598) |

23.29±11.60 (857) |

0.645 |

| Number of lesions treated, mean±SD | 1.23±0.51 (5593/5593) | 1.27±0.56 (2721/2721) |

0.002 | 1.27±0.57 (2039/2039) |

1.26±0.51 (682/682) |

0.452 |

| Reference vessel diameter (mm) mean±SD | 2.95±0.47 (6884) |

2.90±0.46 (3455) |

<0.001 | NA | NA | – |

The time frame provided reflects the number of hours from the onset of AMI symptoms to the time of percutaneous coronary intervention.

Halfway through the E-Five Registry's enrolment, the case report form was modified to gather further detail about patients' baseline clinical characteristics, including renal function and the time between the onset of AMI symptoms and percutaneous coronary intervention. Thus, the denominator reflects the total number of patients in which the modified case report form was used.

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; DM, diabetes mellitus; ITDM, insulin-treated diabetes mellitus; MI, myocardial infarction; NITDM, non-insulin-treated diabetes mellitus; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Compared with NITDM patients, ITDM patients tended to be older, female and more frequently non-smokers. ITDM patients also had a higher incidence of hypertension and moderate–to-severe renal impairment than NITDM patients and were more likely to have undergone previous coronary revascularisation.

Clinical outcomes

Of the 8314 registry patients, 12-month follow-up data were available for 7832 (94.2%).

Major adverse cardiac events

DM patients experienced a higher MACE rate than non-DM patients (table 2). Of the MACE components, DM patients had higher rates of death and, in particular, cardiac-related death and TLR than non-DM patients. The rate of MI between DM and non-DM patients was not significantly different, however.

Table 2.

Comparison of 12-month clinical outcomes between diabetic and non-diabetic patients enrolled in the E-Five Registry

| Outcome | Non-DM | DM | |

| (n=5269) | (n=2563) | p Value | |

| % (n) | % (n) | (adjusted*) | |

| MACE | 6.4 (339) | 9.7 (248) | <0.001 |

| Death-all | 1.7 (87) | 4.1 (104) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac-related death | 1.2 (65) | 2.7 (70) | <0.001 |

| MI | 1.5 (81) | 1.8 (47) | 0.531 |

| Q wave | 0.4 (19) | 0.5 (12) | 0.282 |

| Non-Q wave | 1.2 (63) | 1.4 (35) | 0.928 |

| Emergent CABG | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | NA |

| TLR | 4.0 (213) | 5.3 (136) | 0.028 |

| CABG | 0.6 (31) | 0.7 (19) | 0.322 |

| PTCA | 3.5 (187) | 4.8 (124) | 0.023 |

| TVR | 4.6 (240) | 5.7 (147) | 0.053 |

| TVR—not target lesion | 0.7 (37) | 0.6 (15) | 0.415 |

| TVF | 6.5 (341) | 8.7 (224) | 0.002 |

| ARC definite stent thrombosis | 0.5 (27) | 0.9 (22) | 0.092 |

| 0–30 days | 0.3 (14) | 0.5 (14) | 0.067 |

| 31–365 days | 0.3 (14) | 0.4 (9) | 0.547 |

| ARC definite and probable stent thrombosis | 0.9 (49) | 1.5 (39) | 0.041 |

| 0–30 days | 0.6 (30) | 1.1 (29) | 0.015 |

| 31–365 days | 0.4 (20) | 0.4 (11) | 0.823 |

| All ARC stent thrombosis | 1.4 (73) | 2.8 (71) | <0.001 |

| 0–30 days | 0.6 (30) | 1.1 (29) | 0.015 |

| 31–365 days | 0.9 (45) | 1.7 (44) | 0.007 |

| Per protocol stent thrombosis | 0.8 (41) | 1.6 (41) | 0.002 |

| 0–30 days | 0.6 (29) | 1.3 (33) | 0.001 |

| 31–365 days | 0.2 (13) | 0.3 (8) | 0.577 |

ARC, Academic Research Consortium; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; MI, myocardial infarction; NA, not applicable; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; TLR, target lesion revascularisation; TVF, target vessel failure; TVR, target vessel revascularisation.

p Values were calculated using logistic regression adjusted for propensity scores. Propensity scores were calculated using the following baseline variables: age, sex, prior MI, prior percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery, acute MI (<72 h), hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) (vs non-LAD), B2C (vs AB1), lesion length (≥27 mm vs <27 mm), and reference vessel diameter (>3.5 mm vs ≤3.5 mm).

ITDM patients, compared with NITDM patients, had a higher rate of MACE (table 3). Of the MACE components, ITDM patients had higher rates of death and cardiac death than NITDM patients. MI and TLR rates were not significantly different between the two groups.

Table 3.

Comparison of 12-month clinical outcomes between insulin-treated diabetics and non-insulin-treated diabetics enrolled in the E-Five Registry

| Outcome | ITDM | NITDM | p Value (adjusted*) |

| (n=644) | (n=1919) | ||

| % (n) | % (n) | ||

| MACE | 12.6 (81) | 8.7 (167) | 0.019 |

| Death-all | 6.7 (43) | 3.2 (61) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac death | 4.5 (29) | 2.1 (41) | 0.004 |

| MI | 1.7 (11) | 1.9 (36) | 0.622 |

| Q wave | 0.2 (1) | 0.6 (11) | 0.299 |

| Non-Q wave | 1.6 (10) | 1.3 (25) | 0.959 |

| Emergent CABG | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | NA |

| TLR | 6.5 (42) | 4.9 (94) | 0.221 |

| CABG | 0.5 (3) | 0.8 (16) | 0.408 |

| PTCA | 6.2 (40) | 4.4 (84) | 0.152 |

| TVR | 7.0 (45) | 5.3 (102) | 0.227 |

| Not target lesion | 0.5 (3) | 0.6 (12) | 0.601 |

| TVF | 11.0 (71) | 8.0 (153) | 0.050 |

| ARC definite ST | 1.2 (8) | 0.7 (14) | 0.305 |

| 0–30 days | 0.8 (5) | 0.5 (9) | 0.370 |

| 31–365 days | 0.6 (4) | 0.3 (5) | 0.295 |

| ARC definite+ prob. ST | 2.2 (14) | 1.3 (25) | 0.158 |

| 0–30 days | 1.6 (10) | 1.0 (19) | 0.253 |

| 31–365 days | 0.8 (5) | 0.3 (6) | 0.195 |

p Values were calculated using logistic regression adjusted for propensity scores. Propensity scores were calculated using the following baseline variables: age, sex, prior MI, prior percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery, acute MI (<72 h), hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) (vs non-LAD), B2C (vs AB1), lesion length (≥27 mm vs <27 mm), and reference vessel diameter (>3.5 mm vs ≤3.5 mm).

ARC, Academic Research Consortium; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; DM, diabetes mellitus; ITDM, insulin-treated diabetes mellitus; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; MI, myocardial infarction; NA, not applicable; NITDM, non-insulin-treated diabetes mellitus; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; ST, stent thrombosis; TLR, target lesion revascularisation; TVR, target vessel revascularisation; TVF, target vessel failure.

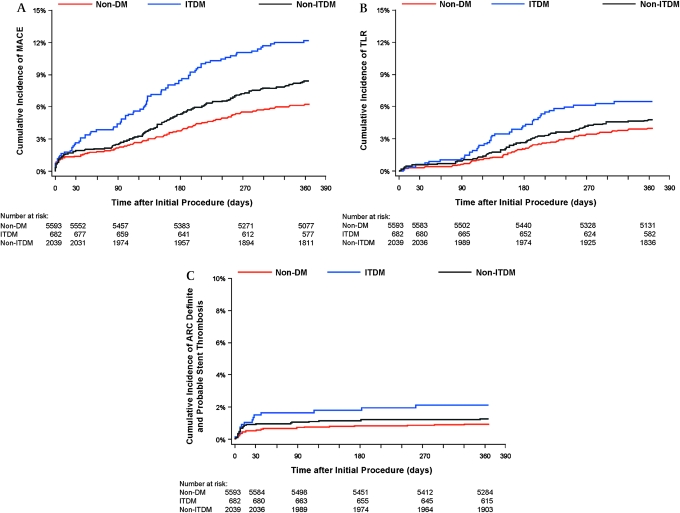

The cumulative incidence of MACE events for the non-DM, NITDM and ITDM patient groups is shown in figure 1A, and the cumulative incidence of TLR for the three patient groups is shown in figure 1B.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing cumulative incidence of (A) major adverse cardiac events (MACE) in non-diabetics (non-DM), insulin-treated diabetics (ITDM) and non-insulin-treated diabetic (NITDM) patients; (B) target lesion revascularisation (TLR) in non-diabetics (non-DM), insulin-treated diabetics (ITDM) and non-insulin-treated diabetic (NITDM) patients; (C) definite or probable stent thrombosis in non-diabetics (non-DM), insulin-treated diabetics (ITDM), and non-insulin-treated diabetic (NITDM) patients.

DM patients, compared with non-DM patients, experienced a higher rate of TVR (table 2). TVR was not significantly different between the ITDM and NITDM groups (table 3). DM patients, compared with non-DM patients, also experienced a higher rate of TVF (table 2). The rate of TVF was higher in ITDM patients compared with NITDM patients. (table 3).

Stent thrombosis

DM patients, compared with non-DM patients, had higher rates of ARC definite and probable stent thrombosis (table 2). There was no statistically significant difference in ARC definite and probable stent thrombosis between the ITDM and NITDM groups (table 3). Most ARC definite and probable stent thrombosis events occurred early, before 30 days post ZES implantation and there were no differences in late ARC definite and probable stent thrombosis among any of the study groups. The cumulative incidence of stent thrombosis in non-DM, NITDM and ITDM patient groups is shown in figure 1C.

Antiplatelet therapy

Most DM and non-DM patients received dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT, aspirin and clopidogrel or ticlopidine) at 30 days (97.6% and 98.1%, p=0.152). The proportions of patients continuing on DAPT declined over time across all groups although by 12 months, patients with DM were more likely than non-DM patients to be receiving DAPT (63.4% vs 60.5%, p=0.016). Patients with ITDM and NITDM were equally likely to receive DAPT at 12 months (63.5% vs 63.3%, p=0.961).

Discussion

In this study of ‘real-world’ patients who underwent ZES stent implantation, DM patients, compared with non-DM patients, were found to have significantly higher rates of MACE, cardiac death, TLR and TVR. ARC definite and probable stent thrombosis was significantly more common in DM patients than non-DM patients. These findings are consistent with previously published registry analyses.10 11

The current study presents the largest analysis of patients in which the outcomes of NITDM compared with ITDM patients implanted with a drug-eluting stent have been studied. The high rate of follow-up at 94.2% is consistent with follow-up rates of other drug-eluting stent registries (88%–95%) and combined with the independent adjudication of all endpoint events and a further 10% random monitoring, leads to a high degree of confidence in these data.11–13 In this study, ITDM patients were found to have significantly greater rates of MACE, all-cause death and cardiac death than NITDM patients, as well as a significantly greater rate of TVF. These results show that although the presence of ITDM did not confer an increased risk of ARC definite or probable stent thrombosis compared with NITDM, the subgroup of diabetic patients treated with insulin was at a statistically higher risk of stent thrombosis than non-DM patients during the first 30 days after the procedure. Most patients, regardless of their diabetes status, received DAPT during this period although DM patients were more likely to continue DAPT for 12 months than non-DM patients. It is unclear what part continued DAPT played in the risk for late stent thrombosis among DM patients.

The association of insulin treatment with increased rates of both all-cause mortality and cardiac death in this registry may have several explanations. Insulin therapy is generally reserved for patients in whom tablet treatment of DM has failed. This suggests that the patients may have had less well controlled DM, for longer duration, at the time of enrolment in the study. The increased co-morbidity associated with longstanding DM may have contributed to the excess rates of all-cause mortality seen in the ITDM group. Most ITDM patients have greater levels of insulin resistance than NITDM patients. Insulin resistance is associated impaired vascular production of nitric oxide, increased endothelin-1 and angiotensin-II and increased vascular production of cytokines.14 These processes work in synergy with the production of pro-coagulant factors, leading to accelerated atherogenesis and increased propensity to thrombosis. Furthermore, stent restenosis is known to be mediated by cellular proliferation cascades influenced adversely by insulin. There remains confusion as to whether the benefits of improved glycaemic control that are achievable with insulin therapy outweigh the possible detrimental effects on the vascular endothelium and its response to injury. Randomised trials have compared outcomes of drug-eluting stent implantation in ITDM and NITDM patients. The number of patients in these subgroup studies has been small, and it is thus difficult to draw conclusions from the available data. In the Sirolimus-Eluting Stent in De Novo Native Coronary Lesions (SIRIUS) substudy, the outcome of drug-eluting stent in 131 patients was investigated with follow-up angiography.15 In this study patients with ITDM (n=38) had higher rates of MACE and TLR than those patients with NITDM (n=93) (p<0.001). In Taxus IV, the 1-year rate of MACE progressively increased from patients without diabetes, to those managed with oral medications (n=213), to those requiring insulin (n=105) (p<0.001).1 Registry analyses of outcomes of drug-eluting stent implantation according to diabetes status have also been published, although these have been in small numbers of patients. In 293 diabetic patients in the Rapamycin-Eluting Stent Evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital (RESEARCH) and Taxus-Stent Evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital (T-SEARCH) registries, insulin treatment was not found to be an independent predictor of MACE.16

The presence of DM is recognised as a predictor of stent occlusion after bare metal stent implantation, and has been shown to be an independent predictor of stent thrombosis in drug-eluting stent implantation.17 The increased incidence of stent thrombosis in DM patients treated with either a paclitaxel-eluting or a sirolimus-eluting stent has recently been confirmed.18 The impact of diabetes status upon the incidence of drug-eluting stent thrombosis is unclear. The e-Cypher registry examined the safety of the sirolimus-eluting stent in daily clinical practice. In the e-Cypher registry, insulin treatment was found to be to be an independent predictor of stent thrombosis in DM patients.11 An increased need for TLR in the DM population was observed in the current study which may be related to the greater complexity of the patients in the E-Five Registry (eg, longer length lesions, small diameter vessels, etc).7 Additionally, the relatively short time-course for follow-up of E-Five Registry patients may favour finding in-stent restenosis rather than new lesions or lesion progression that warrants further intervention.

This study had several limitations. By design it was a registry of unselected patients, and thus there was no randomisation. In addition, the study was confined to patients with a zotarolimus-eluting stent. The non-randomised nature of the study prevented any further analysis of the outcome differences between ITDM and NITDM patients. It should also be noted that the analysis of patients with and without DM enrolled in the E-Five Registry was retrospective in nature.

In conclusion, this study confirmed the safety and effectiveness of the ZES in the treatment coronary artery disease in patients with DM. However, there is clearly a difference in outcomes depending on the treatment regimen, insulin or not. Whether it is the impact of the antecedent duration of diabetes, the insulin therapy itself, the need for insulin therapy or other factors, there is a clear disadvantage to having diabetes, but whether any drug-eluting stent can offset these factors is unclear. Further work is required to define treatment strategies and drug-eluting stent type to bring diabetic outcomes into line with those of non-diabetics.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Janice Hoettels, PA-C and Colleen Gilbert, PharmD of CommGeniX, LLC and Jane Moore, MS in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding: This Registry is funded by the Medtronic Bakken Research Center, Medtronic CardioVascular, Inc.

Competing interests: AKJ, CL, ITM and MTR have served as consultants to Medtronic, Inc. MTR has received research/grant support from Medtronic, Inc and since this paper was written has become VP Medical Affairs, Coronary & Peripheral Division, Medtronic, Inc. JM is a stockholder and employee of Medtronic, Inc. CL has served as a consultant for Angio Score Ltd. ITM has served as an advisory board member for Boston Scientific; MTR has served as a consultant to Abbott Vascular, Cordis Corporation, JenaValve Technology, GmbH, Lombard Medical Technologies plc and Volcano and has received research/grant support from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, CardioBridge GmbH, and Cordis Corporation.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was conducted with the approval of the local ethics committees from the 188 centres participating in this Registry.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hermiller JB, Raizner A, Cannon L, et al. TAXUS-IV Investigators. Outcomes with the polymer-based paclitaxel-eluting TAXUS stent in patients with diabetes mellitus: the TAXUS-IV trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:1206–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirtane AJ, Ellis SG, Dawkins KD, et al. Paclitaxel-eluting coronary stents in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:708–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fajadet J, Wijns W, Laarman G-J, et al. Randomized, double-blind, multicenter study of the Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting phosphorylcholine-encapsulated stent for the treatment of native coronary artery lesions: clinical and angiographic results of the ENDEAVOR II trial. Circulation 2006;114:798–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kandzari DE, Leon MB, Popma JJ, et al. for the ENDEAVOR III Investigators Comparison of zotarolimus-eluting and sirolimus-eluting stents in patients with native coronary artery disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:2440–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leon MB, Mauri L, Popma JJ, et al. A randomized comparison of the ENDEAVOR zotarolimus-eluting stent versus the TAXUS paclitaxel-eluting stent in de novo native coronary lesions: 12-month outcomes from the ENDEAVOR IV trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:543–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain AK, Meredith IT, Lotan C, et al. Real-world safety and efficacy of the Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting stent: early data from the E-Five registry. Am J Cardiol 2007;100(8B):77M–83M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lotan C, Meredith IT, Mauri L, et al. Safety and effectiveness of the Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting stent in real-world clinical practice: 12-month data from the E-Five Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2009;2;1227–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, et al. Clinical endpoints in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation 2007;115:2344–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kandzari DE, Leon MB. Overview of pharmacology and clinical trials program with the zotarolimus-eluting Endeavor stent. J Interv Cardiol 2006;19:405–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar R, Lee TT, Jeremias A, et al. Comparison of outcomes using sirolimus-eluting stenting in diabetic versus nondiabetic patients with comparison of insulin versus non-insulin therapy in the diabetic patients. Am J Cardiol 2007;100:1187–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urban P, Gershlick AH, Guagliumi G, et al. Safety of coronary sirolimus-eluting stents in daily clinical practice: one-year follow-up of the e-Cypher registry. Circulation 2006;113:1434–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simonton CA, Brodie B, Cheek B, et al. Comparative clinical outcomes of paclitaxel and sirolimus-eluting stents: Results from a large prospective multicenter registry—STENT group. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:1214–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waksman R, Buch AN, Torguson R, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes and thrombosis rates of sirolimus-eluting versus paclitaxel-eluting stents in an unselected population with coronary artery disease (REWARDS registry). Am J Cardiol 2007;100:45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seabra-Gomes R. Percutaneous coronary interventions with drug eluting stents for diabetic patients. Heart 2006;92:410–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moussa I, Leon MB, Baim DS, et al. Impact of sirolimus-eluting stents on outcome in diabetic patients: a SIRIUS SIRolImUS-coated Bx Velocity balloon-expandable stent in the treatment of patients with de novo coronary artery lesions) substudy. Circulation 2004;109:2273–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ong AT, Aoki J, van Mieghem CA, et al. Comparison of short- (one month) and long- (twelve months) term outcomes of sirolimus- versus paclitaxel-eluting stents in 293 consecutive patients with diabetes mellitus (from the RESEARCH and T-SEARCH registries). Am J Cardiol 2005;96:358–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA 2005;293:2126–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iijima R, Ndrepepa G, Mehilli J, et al. Impact of diabetes mellitus on long-term outcomes in the drug-eluting stent era. Am Heart J 2007;154:688–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]