Abstract

Pulmonary tumour thrombotic microangiopathy (PTTM) is characterised by wide spread tumour emboli along with fibrocellular intimal proliferation and thrombus formation in small pulmonary arteries and arterioles. PTTM is a rare but fatal complication of carcinoma, but the pathogenesis remains to be clarified. An autopsy case of PTTM caused by gastric adenocarcinoma is described, in which tumour cells in the PTTM lesion had positive immunoreactivity for platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and PDGF receptor (PDGFR), and proliferating fibromuscular intimal cells also showed expression of PDGFR. In addition, the overexpression of PGDF was detected in the alveolar macrophages. These findings suggest that PDGF derived from alveolar macrophages and from tumour cells may act together in promoting fibrocellular intimal proliferation. To the best of the authors' knowledge, the possible involvement of activated alveolar macrophages in PTTM has not been previously reported.

Keywords: Pulmonary thrombotic microangiopathy, gastric cancer, immunohistochemistry, platelet-derived growth factor, macrophages, arteries, gastric cancer, immunocytochemistry, lung, molecular pathology

Pulmonary tumour thrombotic microangiopathy (PTTM) is a rare pulmonary complication observed in 0.9–3.3% of autopsies of patients with metastatic carcinomas that are characterised by multiple tumour microemboli associated with proliferation of intimal fibromuscular cells and the formation of fibrin thrombi in the small pulmonary arteries and arterioles.1 2 Clinically, patients with PTTM often present with progressive dyspnoea and severe pulmonary hypertension, and develop acute right side heart failure.3

We report here an autopsy case of PTTM caused by a gastric carcinoma. In the present study, the expression PDGF and PDGF receptor (PDGFR) were detected in tumour cells. Moreover, the overexpression of PDGF was detected in alveolar macrophages. A possible contribution of alveolar macrophages in PTTM is discussed.

A 64-year-old male patient was referred to Nagasaki University Hospital for treatment of a gastric tumour. Physical examination including auscultation was normal. Gastrointestinal endoscopy showed thickening and tortuosity of folds of the stomach wall, so-called leather bottle-like appearance. An abdominal CT scan showed a thickening of the stomach wall and swelling of multiple lymph nodes. Remarkable symptoms of respiration were not detected. A chest CT scan was negative.

At autopsy, the stomach wall was found to be diffusely thickened, and ulceration was identified in the prepyloric area. Abdominal lymph nodes were markedly involved. The left and right lungs weighed 310 g and 340 g, respectively. No macroscopic thrombi were found in the pulmonary arteries or main branches, and neither gross emboli nor visible nodules of cancer metastasis were noted on the cut surfaces of the lungs.

Light microscopy showed a poorly differentiated carcinoma infiltrating the wall of the stomach. Lymphatic vessel infiltration was remarkable with multiple involvement of abdominal lymph nodes. In the lungs, most of the small arteries and arterioles were stenotic or occluded by fibrocellular intimal proliferation and thromboemboli with or without tumour cells. In some pulmonary vessels, organised thromboemboli with recanalisation were observed. All of these pathological features of the pulmonary vessels were consistent and characteristic of PTTM.

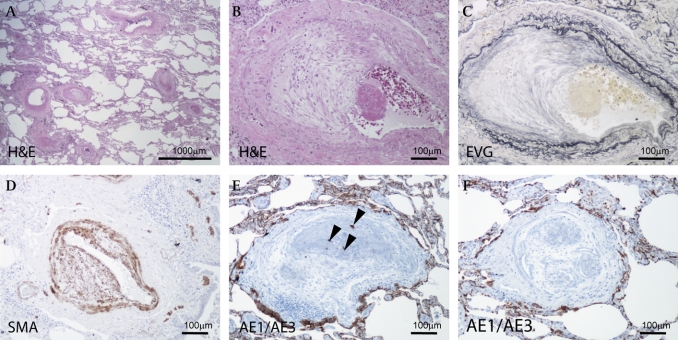

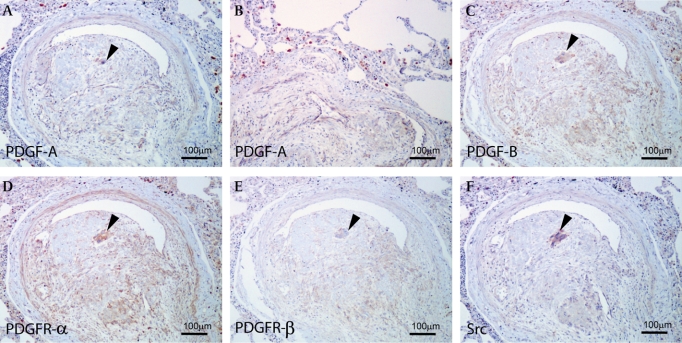

Immunohistochemically, proliferating fibromuscular cells in the intima were positive for α-smooth muscle actin (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) (figure 1D). Immunoreactivity of pancytokeratin (AE1/AE3, Dako) was indicated in the carcinoma cells (figure 1E) in a pulmonary artery. Moderate expressions of PDGF (figure 2A,C) and PDGFR (figure 2D,E) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) were localised to the fibromuscular intimal cells, smooth muscle and endothelial cells in constricted small arteries. The immunoreactivity of PDGF and PDGFR was also detected in tumour cells (figure 2A,C–E). In addition, overexpression of PGDF-A was detected in alveolar macrophages around small pulmonary arteries with constricted or plexiform remodelling (figure 2A,B). Phosphorylated Src (Acris Antibodies, Hiddenhausen, Germany) expression was also identified in the tumour cells in the vessels (figure 2F).

Figure 1.

(A) Stenosis and obstruction of many pulmonary arteries and arterioles are shown. Bar, 1000 μm. (B, C) A pulmonary artery showing fibrous thickening of intima and fibrin thrombus (B: H&E stain; C: elastic van Gieson stain). (D) Intimal proliferating fibromuscular cells are positive for α-smooth muscle actin. (E, F) Fibrin thrombus with (E) or without (F) adenocarcinoma cells. Immunoreactivity of pancytokeratin antibody (AE1/AE3) is indicated in the carcinoma cells (F). (E) Arrowheads indicate cancer cells in the vessel. (B–F) Bar, 100 μm.

Figure 2.

(A) Carcinoma cells and endothelial cells are immunopositive for platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-A. (B) Alveolar macrophages show the overexpression of PDGF-A in the PTTM lesion. (C) Carcinoma cells, endothelial cells and fibromuscular cells are immunopositive for PDGF-B. (D, E) The expression of PGDF receptors (PDGFRs) (PDGFR-α (D); PDGFR-β (E)). PDGFR-α and -β were detected in tumour cells and fibromuscular cells. PDGFR-α were detected in endothelial cells. (F) Immunoreactivity of phosphorylated Src was found in the tumour cells. (A, C, D, E, F) Arrowheads indicate cancer cells in the vessel. (A–F) Bar, 100 μm.

Discussion

Hervay et al speculated that attachment of tumour cell emboli may damage endothelial cells and release PDGF in PTTM.1 The currently held mechanism of PTTM is that tumour cells occlude the small arteries and arterioles, and also activate coagulation systems and release inflammatory mediators and growth factors.2 4 However, the molecular mechanism and associated factors in PTTM remain to be determined.

PDGF is a key mediator in proliferation and migration of smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts.5 In the presenting case, PDGF, PDGFR and phosphorylated Src expression was found in tumour cells in a PTTM lesion. These suggested an autocrine function of PDGF in the cancer cells.6–8 In addition, overexpression of PDGF was found in alveolar macrophages and PDGFR in intimal mesenchymal cells in the pulmonary arterial wall. Our findings suggest that activated alveolar macrophages in the PTTM lesion contributed cooperatively with tumour cells to proliferation of fibromuscular cells and had a critical role in the onset and/or progression of PTTM via expression of PDGF.

Take-home messages.

Pulmonary tumour thrombotic microangiopathy (PTTM) is a rare pulmonary complication seen in patients with metastatic carcinomas.

Clinically, patients with PTTM often present with progressive dyspnoea and severe pulmonary hypertension, and develop acute right side heart failure.

PTTM is characterised by multiple tumour microemboli associated with proliferation of intimal fibromuscular cells and the formation of fibrin thrombi in the small pulmonary arteries and arterioles.

Activated alveolar macrophages in the PTTM lesion contributed cooperatively with tumour cells and had a critical role in the onset and/or progression of PTTM via expression of PDGF.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This study was conducted with the approval of the Nagasaki University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.von Herbay A, Illes A, Waldherr R, et al. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy with pulmonary hypertension. Cancer 1990;66:587–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sato Y, Marutsuka K, Asada Y, et al. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy. Pathol Int 1995;45:436–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao DX, Flieder DB, Hoda SA. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy: an often missed antemortem diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2001;125:304–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chinen K, Kazumoto T, Ohkura Y, et al. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy caused by a gastric carcinoma expressing vascular endothelial growth factor and tissue factor. Pathol Int 2005;55:27–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heldin CH, Westermark B. Mechanism of action and in vivo role of platelet-derived growth factor. Physiol Rev 1999;79:1283–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshida K, Yasui W, Ito H, et al. Growth factors in progression of human esophageal and gastric carcinomas. Exp Pathol 1990;40:291–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katano M, Nakamura M, Fujimoto K, et al. Prognostic value of platelet-derived growth factor-A (PDGF-A) in gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg 1998;227:365–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gelderloos JA, Rosenkranz S, Bazenet C, et al. A role for Src in signal relay by the platelet-derived growth factor alpha receptor. J Biol Chem 1998;273:5908–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]