Abstract

Hydrogen bonds between backbone amides are common in folded proteins. Here, we show that an intimate interaction between backbone amides likewise arises from the delocalization of a lone pair of electrons (n) from an oxygen atom to the antibonding orbital (π*) of the subsequent carbonyl group. Natural bond orbital analysis predicted significant n→π* interactions in certain regions of the Ramachandran plot. These predictions were validated by a statistical analysis of a large, non-redundant subset of protein structures determined to high resolution. The correlation between these two independent studies is striking. Moreover, the n→π* interactions are abundant, and especially prevalent in common secondary structures such as α-, 310-, and polyproline II helices, and twisted β-sheets. In addition to their evident effects on protein structure and stability, n→π* interactions could play important roles in protein folding and function, and merit inclusion in computational force fields.

Electron delocalization is a unifying theme behind many fundamental concepts of chemistry, including resonance and hyperconjugation. An especially important biological manifestation of electron delocalization is the hydrogen bond, which involves the delocalization of the lone pair (n) of the hydrogen-bond acceptor over the antibonding orbital (σ*) of the hydrogen-bond donor1–4. Nearly 75 years ago, Mirsky and Pauling wrote: “The importance of the hydrogen bond in protein structure can hardly be overemphasized”5. We report on a contributor to protein structure, termed the “n→π* interaction”, that arises from electron delocalization analogous to that of the hydrogen bond.

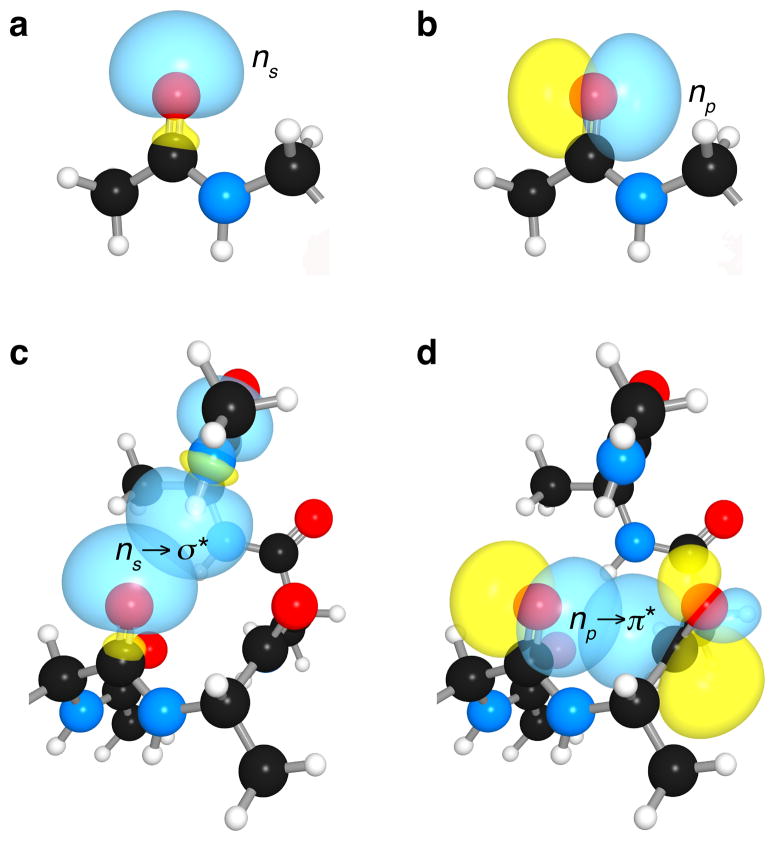

The extent of overlap between donor and acceptor orbitals is governed by their relative spatial orientation. Contrary to the expectations of valence shell electron pair repulsion (VSEPR) theory, the two lone pairs of divalent oxygen do not occupy equivalent orbitals6 that resemble “rabbit ears”7,8. For example, the lone pairs of a carbonyl oxygen are not in sp2 hybrid orbitals, but reside in non-degenerate s-rich and p-rich orbitals. The s-rich lone pair (ns) has ~60% s- and 40% p-character; whereas the p-rich lone pair (np) has ~100% p-character. In an amide oxygen, ns is aligned with the σ bond of the carbonyl group (Fig. 1a), and np is orthogonal to the π bond of that group (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1. Kinship of hydrogen bonds and n→π* interactions in an α-helix.

a, s-rich lone-pair of an amide oxygen. b, p-rich lone-pair of an amide oxygen. c, ns→σ*: hydrogen bond in an α-helix. d, np→π*: n→π* interaction in an α-helix.

We postulate that an α-helix avails both of these lone pairs. In particular, ns delocalizes over the antibonding orbital (σ*) of an N–H bond to form a hydrogen bond between residues i and i+4 in a polypeptide chain (Fig. 1c),1–4,9. Likewise, np is poised to delocalize over the antibonding orbital (π*) of the i+1 carbonyl group (Fig. 1d). Model studies investigating peptides, peptoids, and related small molecules have revealed that the ensuing n→π* interaction can alter conformational preferences10–20.

Here, we perform a thorough survey of protein conformational space for significant n→π* interactions. First, we employ calculations to anticipate the main-chain dihedral angles that give rise to significant n→π* interactions. We then perform a statistical analysis of a large, non-redundant subset of high-resolution protein crystal structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB21) to search for such interactions. The results of these calculations and structural analyses indicate that n→π* interactions are abundant and widespread in proteins.

Results

Prevalence of n→π* interactions

We sought to identify regions of protein conformational space that could contain significant n→π* interactions (Fig. 2). We did so by creating and analyzing a computational library of allowed conformations. This library was generated with a tetramer of alanine residues capped at its N-terminus with an acetyl group and at its C terminus with a methylamino group (AcAla4NHMe). The conformations calculated by natural bond orbital (NBO) methods to have favorable n→π* interaction energies (En→π*; Table S1) are depicted in a Ramachandran-type plot in Fig. 2b. Briefly, two broken elliptical regions are favored, one in each half of the ψ range. The uppermost region stretches from the allowed, through partially allowed β-region, and into the αL conformations; the other spans the allowed through partially allowed α-region and disallowed regions in the lower-right quadrant of the plot.

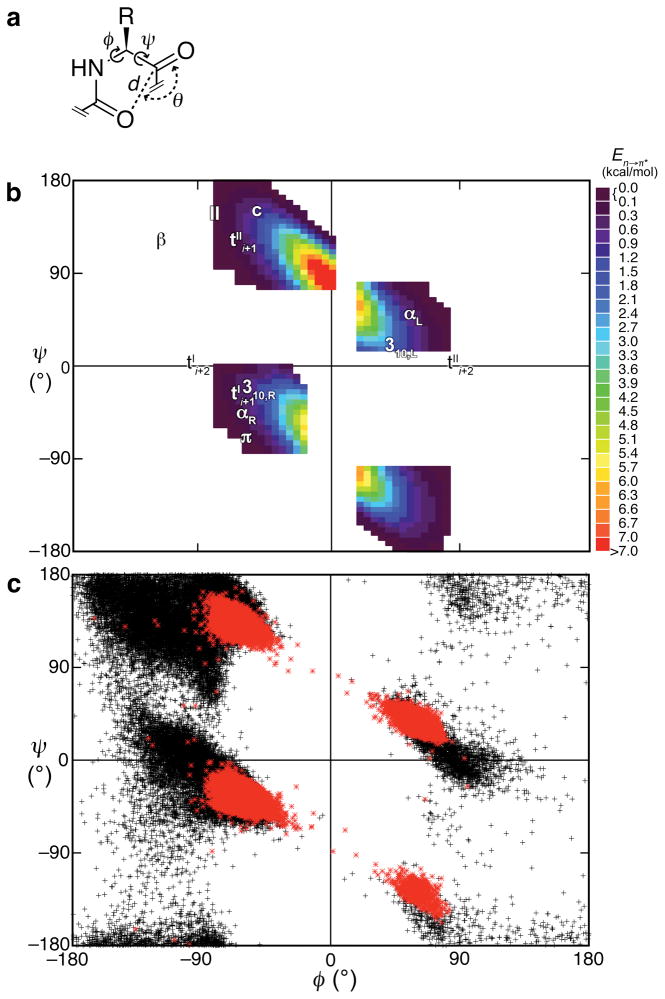

Figure 2. Ramachandran plots of n→π* interactions.

a, Definitions of dihedral angles φ (C′i−1–Ni–Cαi–C′i) and ψ (Ni–Cαi–C′i–Ni+1), distance d, and planar angle θ. Criteria for an n→π* interaction in the crystallographic analyses: d ≤ 3.2 Å; 99° ≤ θ ≤ 119° b, Computational data showing the energy of an n→π* interaction for 836 φ, ψ angles. Common secondary structures are indicated. c, Crystallographic data showing all residues in 1731 high-resolution structures (black) and those that meet the criteria in panel a (red). Nineteen of those residues had d ≤ 2.60 Å (Table S2).

The NBO analyses predict what protein conformations could give rise to n→π* interactions. Do actual proteins avail those conformations and thus employ n→π* interactions? To answer this question, we generated a subset of high-resolution (≤1.6 Å), and non-redundant (≤30% pairwise sequence identity) X-ray crystal structures from the PDB. Within this set, n→π* interactions between backbone carbonyl groups of consecutive residues (residue pairs) were identified using the operational definition given in Fig. 2a. At distances ≤3.2 Å, the van der Waals’ surfaces of the two carbonyl groups interpenetrate, putting these contacts in the realm of quantum mechanics rather than classical electrostatics16,20; the allowed angles are reminiscent of the Bürgi–Dunitz trajectory for nucleophilic attack on a carbonyl carbon (~109°). Residue pairs that tested positive for n→π* interactions are depicted in red on a Ramachandran plot, Fig. 2c. For comparison, the φ,ψ angles for all other residue pairs from the whole subset are depicted in black. As might be expected, the observed n→π* interactions occur in allowed regions of Ramachandran space, Fig. 2c. What is remarkable, however, is that the favored regions for n→π* interactions anticipated by the computational analyses correspond to those identified in the PDB search. The correlation is not exact because the hot spots identified by our computational analyses report on n→π* interactions only, without any steric considerations, and therefore cover regions of conformational space that are disallowed in protein structures.

Thus, both the computational and the crystallographic analyses suggest widespread and abundant n→π* interactions in the allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot. Importantly, we found n→π* interactions in all 1731 of the selected protein crystal structures, with proportions in the range 5–97% (mean: 34%). A breakdown of these data by secondary structure is detailed in Table 1. n→π* interactions were especially prevalent in right- and left-handed α-helices, but were less common in β-strands. One quarter of the residues in left-handed polyproline II (PII) helices participate in n→π* interactions. A similar fraction was found in residues not in regular secondary structures, on the right-hand side of the Ramachandran plot (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Potential n→π* interactions in different types of secondary structure.

| Dipeptide | α-helix | β-sheet | PII helix | Other secondary structures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of pairs | Those with potential n→π* interactions | Total number of pairs | Those with potential n→π* interactions | Total number of pairs | Those with potential n→π* interactions | Total number of pairs | Those with potential n→π* interactions | |

| Xaa–Ala | 11384 | 9367 (82%) | 2786 | 80 (2.8%) | 24 | 6 (25%) | 185 | 47 (25%) |

| Xaa–Gly | 2713 | 2188 (81%) | 2036 | 67 (3.3%) | 9 | 0 | 156 | 9 (5.7%) |

| Xaa–Pro | 544 | 518 (95%) | 527 | 193 (37%) | 65 | 12 (18%) | 324 | 63 (12%) |

| Xaa–All | 88124 | 63792 (72%) | 38657 | 1166 (3%) | 227 | 58 (25%) | 2588 | 427 (16%) |

Significance of Xaa–Pro dipeptides

The mean φ angle for the residues on the left-hand side of the Ramachandran plot—i.e., that occupied by right-handed α-helices and β-strands—involved in n→π* interactions is −63.3° ± 5.6° (Fig. 2c), which is close to the distribution of φ angles for proline residues (−65.0° ± 10.6°). This correlation, as well as prior results with a peptidic model system11,16, suggested that proline could be particularly suited for engaging in an n→π* interaction when found at the acceptor (i+1) position and led us to examine Xaa–Pro dipeptides (where Xaa is any amino acid), using Xaa–Ala and Xaa–Gly as control pairs. We found that Xaa–Pro pairs contributed significantly to the prevalence of n→π* interactions in both α-helices and β-strands (Table 1). For α-helices, the amino-acid preference for n→π* interaction decreased in the order: Pro > Ala > Gly > all other amino acids, with almost all the proline residues participating in n→π* interactions. For β-strands in which n→π* interactions were found, the amino-acid preference decreased in the order: Pro ≫ Gly > all, with a ten-fold preference for proline over glycine. In PII helices, the distribution was less and differently skewed, all = Ala > Pro ≫ Gly; we return to this important point below. In regions without regular secondary structure, a similar distribution was observed, with proline engaging in proportionally fewer n→π* interactions than alanine and all other residues, but more than glycine.

Detailed geometry of n→π* interactions

We examined in detail the Oi–1···Ci distance (d, Fig. 2a) as well as the Oi–1···Ci=Oi angle (θ, Fig. 2a) for Xaa–Pro, Xaa–Gly, and Xaa–Ala dipeptides in protein structures. For α-helices, β-strands, PII helices, and runs of residues with no secondary structure, we found that the mean Oi–1···Ci distance in Xaa–Pro was shorter by ~0.1 Å than the same distance in Xaa–Gly and Xaa–Ala (Fig. 3). In α-helices, the mean Oi-1···Ci=Oi angle was 107.2° ± 6.5° for Xaa–Pro motifs, compared with 103.0° ± 7.6° for Xaa-Gly and 102.9° ± 4.6° for Xaa–Ala. This wider angle is close to the Bürgi–Dunitz trajectory. In β-strands, the mean Oi-1···Ci=Oi angle was 103.8° ± 13.5° for Xaa–Pro, compared with 118.1° ± 9.3° for Xaa–Ala and 112.7° ± 11.3° for Xaa–Gly.

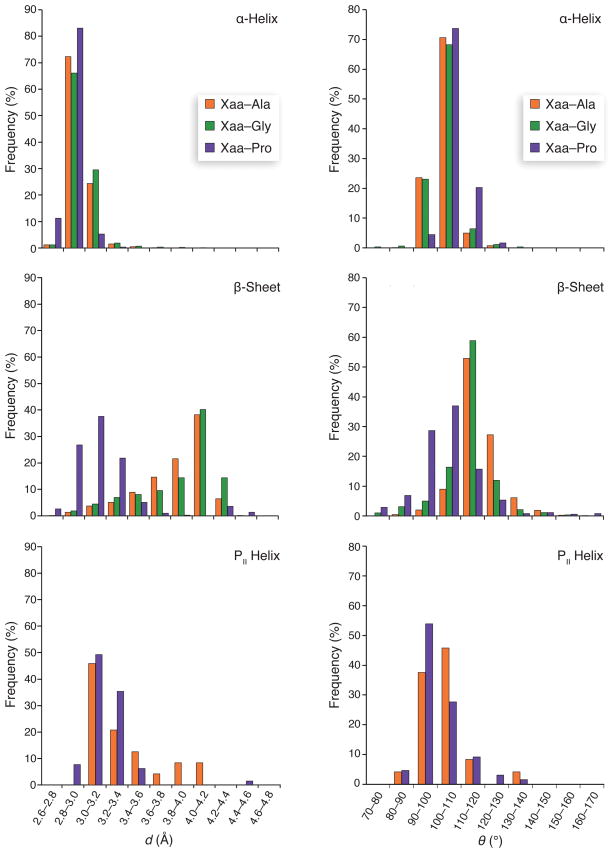

Figure 3. Histograms of d and θ values for Xaa–Ala, Xaa–Gly, and Xaa–Pro dipeptides in α-helices, β-sheets, and PII helices.

Mean values (± SD) of d and θ were as follows. α-Helix: Xaa–Ala, d = 2.97 ± 0.10 Å, θ = 102.9 ± 4.7°; Xaa–Gly, d = 3.01 ± 0.17 Å, θ = 103.0 ± 7.6°; Xaa–Pro, d = 2.89 ± 0.10 Å, θ = 107.2 ± 6.5°. β-Sheet: Xaa–Ala, d = 3.87 ± 0.32 Å, θ = 118.1 ± 9.3°; Xaa–Gly, d = 3.89 ± 0.36 Å, θ = 112.7 ± 11.3°; Xaa–Pro, d = 3.17 ± 0.33 Å, θ = 103.8 ± 13.5°. PII helix: Xaa–Ala, d = 3.16 ± 0.33 Å, θ = 97.7 ± 9.5°; Xaa–Pro, d = 3.01 ± 0.21 Å, θ = 95.6 ± 8.7°. Mean values of d for Xaa–Pro were smaller than those for Xaa–Ala and Xaa–Gly in each secondary structure, according to Student’s t-test (p < 0.05, one-tailed test, number of observations as in Table 1). Mean values of θ for Xaa–Pro were larger than those for Xaa–Ala and Xaa–Gly in α-helices, but smaller than those for Xaa–Ala and Xaa–Gly in β-sheets, according to Student’s t-test (p < 0.05, one-tailed test, number of observations as in Table 1). The number of Xaa–Gly dipeptides in PII helices was too small for their inclusion.

Insufficient data were available for Xaa–Gly pairs in PII helices due to the requisite non-redundancy of the dataset. Many collagen structures, which consist of three intertwined glycine- and proline-rich PII helices15, were removed because of similarity through their Pro–Hyp–Gly repeats. To address this issue explicitly, we examined 15 high-resolution (≤1.6 Å) structures of collagen-like peptides. We found the mean value of d in Xaa–Pro dipeptides to be shorter than in Xaa–Gly, by ~0.1 Å, similar to the difference found in α-helices and β-strands. The mean Oi–1···Ci=Oi angles were, however, shallower (80.9° ± 2.2° for Xaa–Gly; 89.4° ± 2.4° for Xaa–Pro) than that for an optimal n→π* interaction, which precluded their designation as n→π* interactions in the original search (Table 1).

Continuity of n→π* interactions

To identify only definitive cases of n→π* interactions, we employed a conservative operational definition in our PDB search (Fig. 2a). The value of En→π* is, however, a continuum that depends on the values of d and θ. The NBO analyses indicate significant conformational stabilization offered by the n→π* interaction, even at angles outside the range 99° ≤ θ ≤ 119° (Fig. 4a). In other words, significant n→π* interactions are likely to be more abundant than implied by the constrained PDB data depicted in Fig. 2c and 3. For example, the mean Oi–1···Ci=Oi angle in PII helices was only slightly shallower than 99° for Xaa–Ala (97.7° ± 9.5°) and Xaa–Pro (95.6° ± 8.7°) dipeptides.

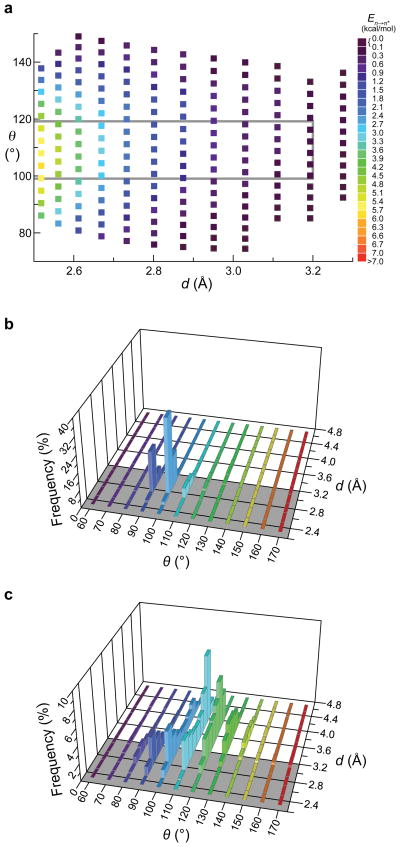

Figure 4. Values of d and θ in n→π* interactions.

a, Energy of the n→π* interactions for values of d and θ in the right-handed helical region of the Ramachandran plot (i.e., −180 ≤ φ ≤ 0; −180 ≤ ψ ≤ 0). The criteria in Fig. 2a are obeyed within the gray rectangle. b, Frequency of values of d and θ among residue pairs (132149) in an α-helix (Table S3). c, Frequency of values of d and θ among residue pairs (221469) not in an α-helix (Table S4). Combined, the plots in panels b and c include all residue pairs (353618) in 1731 high-resolution structures; n.b., there are more data plotted here than are listed in Table 1, as the latter were culled for four-residue sequences, whereas as the data used in this figure were from residue pairs. The frequency of residue pairs with d ≤ 3.2 Å (Fig. 2a) emerge from the gray plane.

Predetermination of n→π* interactions?

Do n→π* interactions stabilize protein structures, or are their signature Oi–1···Ci distances and Oi–1···Ci=Oi angles merely an artifact of protein topology? To address this question, we analyzed the relationship between d and θ for all residue pairs in the 1731 high-resolution structures used to generate Fig. 2c and 3. We found that α-helices, the most prevalent secondary structure in the dataset, are dominated by values of d ≤ 3.2 Å and θ near 100° (Fig. 4b), as expected from Fig. 3. The tendency of θ to be near 100° when d ≤ 3.2 Å is also evident in residues pairs that are not in an α-helix (i.e., largely unconstrained by secondary structure; Fig. 4c). The value of θ varies widely, however, when d > 3.2 Å, an unexpected result if the distances and angles are topological artifacts. In other work, some of us have discovered that in the absence of an n→π* interaction, the donor group neither makes a short contact with the acceptor (d > 3.2 Å) nor resides along the Bürgi–Dunitz trajectory (θ ≈ 125°)20. These results suggest that n→π* interactions are not an artifact of protein topology.

Protein structures with many or few n→π* interactions

Some of the 1731 structures that we examined had an inordinately high or low fraction of residues in n→π* interactions, according to the criteria in Fig. 2a. These structures are listed and depicted in Table S5. In 8 structures, >80% of the residues participate in n→π* interactions. These are small α-helical proteins; five comprise single α-helices, three have helix-turn-helix structures. Interestingly, almost all of them are coiled–coil proteins, and the extensive n→π* interactions could enhance the rigidity of those coiled coils. At the other end, 39 structures have <10% of the residues in n→π* interactions. In these structures, almost all the secondary structure is β-sheet, and only four structures have any residues in α-helices. For these structures, the proportion of residues not in regular secondary structures is slightly greater than in the entire data set (37% versus 34%). Proteins in this group include streptavidin, tumor necrosis factor-α, and a variety of carbohydrate-binding proteins.

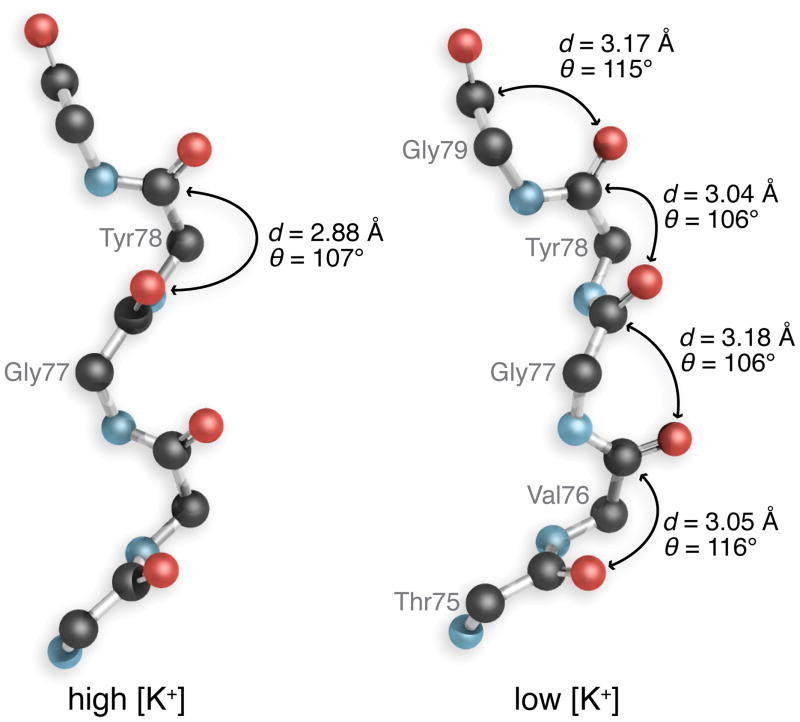

We searched the PDB for runs of four or more n→π* interactions not contained within common secondary structural elements in proteins. This search returned only eight hits from a possible 7833 sets of four residues. Detailed examination showed that these hits were located between α-helices or β-strands, except for one that formed part of an iron-binding site (residues 246–251 inclusive in cytosine deaminase, PDB code 1ra0 22, of which His246 is a ligand to the iron ion). Most notably, however, in a wider search of the PDB, we found a run of four n→π* interactions in the selectivity filter of the potassium ion channel from Streptomyces lividans (KcsA; Fig. 5)23, while n→π* interactions were nearly absent in the structure of the filter region determined at high K+ concentration.

Figure 5. Potential n→π* interactions in the selectivity filter of the KcsA potassium ion channel.

A single chain of the tetrameric channel determined at a high K+ concentration (PDB code 1k4c) structure was superposed on that determined at a low K+ concentration (PDB code 1k4d). Superpositions were carried out by the Secondary Structure Matching service at EBI (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/msd-srv/ssm).

Discussion

n→π* interactions in quadrants of the Ramachandran plot

Our computational and structural analyses reveal abundant and widespread n→π* interactions in three quadrants of the Ramachandran plot. This finding has implications for common secondary structures, as follows.

The φ = 0 to −180°, ψ = 0 to −180° quadrant houses the most common right-handed helices such as α-, 310-, and π-helices. The stabilization offered by the n→π* interaction to these secondary structures as determined by NBO analyses is 0.5 kcal/mol for an α-helix (φ,ψ = −57°, −47°), 1.3 kcal/mol for a 310-helix (−49°,−26°), and 0.1 kcal/mol for a π-helix (−57°,−70°). For comparison, experiments have revealed that the n→π* interaction in FmProOMe (which has an ester carbon rather than amide as the acceptor) has En→π* ~0.7 kcal/mol11.

The existence of an n→π* interaction in α-helices is supported by much evidence. Two diagnostic signatures of the quantum mechanics that underlie the n→π* interaction16 have been observed in α-helices: pyramidalization of the acceptor carbonyl group24 and polarization of its π-electron cloud25. The origin of these perturbations was unknown. Moreover, detailed analyses of peptides have demonstrated that n→π* interactions provide significant conformational stabilization at d ≤ 3.2 Å10,11,16,20. Such distances are encountered in 72% of α-helical residues (Table 1).

In addition to stabilizing the α-helix, we hypothesize that the n→π* interaction could have an important role in α-helix formation. The nucleation of an α-helix is energetically unfavorable: forming the characteristic i→i+4 hydrogen bond necessitates the restriction of at least six main-chain dihedral angles, and a consequent loss in conformational entropy; and the enthalpy of a helix–coil transition has been estimated to be ~0.9 kcal/mol/residue26. Additionally, considerable enthalpic cost is incurred because the amidic dipoles of adjacent residues repel each other in an α-helical conformation27. The n→π* interaction, which operates between the i and i+1 residues, could mitigate these energetic penalties. Consistent with this proposal, we note that proline is a strong helix initiator28–31, and has a high propensity for engaging in the n→π* interaction (Table 1)10–13,16. Moreover, the purported intermediacy of the 310-helix32–35 and its prevalence at α-helix termini suggest that the strong n→π* interaction within a 310 helix (1.3 kcal/mol) could have an important role in α-helix formation. The short Oi–1···Ci distance induced by an n→π* interaction (Fig. 1d) causes lateral compaction of the α-helix that could align the hydrogen bond donor and acceptor groups for a stronger i→i+4 hydrogen bond (Fig. 1c).

Neither parallel nor anti-parallel β-strands of the φ = 0 to −180°, ψ = 0 to 180° quadrant exhibit significant n→π* interactions. In these extended structures, adjacent carbonyl groups are too distal for an intimate interaction (d > 3.2 Å). Nonetheless, a significant proportion of β-sheets have a twist with d < 3.2 Å. It is plausible that the n→π* interaction provides a consequential conformational stabilization to these twisted β-strands, which then form twisted β-sheets. Occasionally, β-strands have an amplified right-handed twist resulting in local disruption of the β-sheet structure. Such β-bulges are involved in the dimerization of immunoglobulin domains and can assist in enclosing the active sites of proteins36–39. Two common types of β-bulges, the G1 and wide types, adopt φ and ψ dihedral angles indicative of considerable n→π* interactions. In particular, of all sets of three residues comprising G1 bulges in our dataset identified using Promotif40, the 25% that partake in n→π* interactions have constrained mean (φ, ψ) angles (Residue X: −68.0° ± 5.5°,130.4° ± 6.6°; Residue 1: 58.4° ± 17.6°, 36.4° ± 11.0°; Residue 2: −68.7° ± 6.8°, 136.9° ± 6.5°) which place them in energetic ‘hotspots’ on the Ramachandran plot. The contribution of n→π* interactions within PII helical strands to the conformational stability of the collagen triple helix has been described previously15.

β-Turns have been implicated in protein folding41,42. Our computational analyses indicate that n→π* interactions confer conformational stability to the i+1 residues in common type I and type II β-turns (Fig. 2b). As in an α-helix (Fig. 1c,d), the donor oxygen participates in a hydrogen bond (here, i→i+3) along with the n→π* interaction. We note that the i+1 residues of β-turns, like all of the residues in a PII helix, adopt their conformation without the aid of local or intra-secondary structure hydrogen bonds. Accordingly, the n→π* interaction could have a special role to play in the stability of these structures.

Although they occur less frequently than their right-handed counterparts in proteins, left-handed helices of the φ = 0 to 180°, ψ = 0 to 180° quadrant play distinctive structural and functional roles in substrate specificity, cofactor binding, and protein–protein interactions43. For example, the left-handed α-helical conformation of MPK-3 is critical for the binding and subsequent negative regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)44. The n→π* interaction could play an important role in the stability and folding of the left-handed α-helices and 310 helices.

Possible functional roles and other implications

Could n→π* interactions contribute to protein function? Their prevalence in canonical secondary structures (Table 1) implies a broad impact. We note, however, an especially intriguing situation in a non-canonical structure. The selectivity filter of the potassium channel from Streptomyces lividans (KcsA23) has a run of n→π* interactions, but only in the structure determined at low K+ concentration (Fig. 5). The filter is occluded in this ‘closed’ state, and only two dehydrated K+ ions are present in the channel. At high K+ concentration, n→π* interactions do not appear to play a significant role, and four dehydrated K+ ions are evident within the channel. These observations suggest that main-chain oxygens in the potassium ion channel can participate in n→π* interactions or bind to K+ ions, but not both.

Our results suggest several areas for future investigation. For example, we note that the formation of n→π* interactions could be cooperative, as the polarization of an acceptor C′i+1=Oi+1 group makes Oi+1 into a better donor. We speculate that the conduit provided by n→π* interactions could facilitate the tunneling of electrons through proteins45. Finally, we urge the inclusion of n→π* interactions in relevant computational force fields.

Methods

Computational Analyses

Geometry optimization and frequency calculation for an AcAla4NHMe model peptide were performed at the B3LYP/6-31+G* level of theory with all the amide bonds locked in the trans conformation46. Frequency calculations of the optimized structure yielded no imaginary frequencies. The library of allowed conformations was generated by varying the φ and ψ dihedral angles systematically in increments of 5°. Natural bond orbital (NBO) analyses were performed at the B3LYP/6-311+G(2d,p) level of theory on each conformation. The NBO method transforms a calculated wavefunction into a localized form, which corresponds to the lone pair and bond elements of the Lewis structure47. The stabilization afforded by the n→π* interaction, En→π*, was estimated by using second-order perturbation theory as implemented in NBO 5.0. Orbital depictions were generated with NBOView 1.1.

PDB Analyses

A subset of high-resolution (≤1.6 Å), and non-redundant (pairwise sequence identity ≤30%) protein X-ray crystal structures was collated from the PDB using PISCES48 with data downloaded on 18 December 2007. The following operational definition was used to identify unambiguous examples of n→π* interaction in these proteins: C′i−1=Oi−1···C′i=Oi contacts in which (1) the distance between the amide oxygen (Oi−1) and subsequent amide carbon (C′i) was less than the sum of their van der Waals’ radii (d ≤ rO + rC = 3.2 Å; Fig. 2); and (2) the angle between Oi−1 and C′i=Oi was 99° ≤ θ ≤ 119° (Fig. 2). Distributions of these short contacts were studied as a function of the main-chain dihedral angles φ and ψ. α-Helix and β-sheet assignments were made with PROMOTIF40, which uses modified Kabsch and Sander criteria49 to assign secondary structure. PPII helices were assigned with the method of Stapley50, which assigns regions of at least four residues in length to be PII helices if their ϕ and ψ angles fall within angle constraints particular to this secondary structural class and do not fall into any structural class according to the Kabsch and Sander criteria49. Residue pairs were only considered to belong to a structural class if they were residues X and Y in sequence WXYZ in which all four amino acids were assigned to that structural class, with the exception of the data shown in Fig. 4b and 4c, in which only residue pairs (i.e., X and Y) were considered.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Spencer, J. Harvey, A. Mulholland, B. Bromley, M. D. Shoulders, B. R. Caes, C. N. Bradford, M. J. Palte, and E. Moutevelis for helpful discussions. Financial support was provided by the University of Bristol and the BBSRC of the UK (grant D003016) to D.N.W., and grant R01 AR044276 (NIH) to R.T.R.

Footnotes

Author contributions

D.N.W. and R.T.R. conceived the project. G.JB. and D.N.W. designed the PDB analyses; G.J.B. performed the PDB analyses. A.C. and R.T.R. designed the computational analyses; A.C. performed the computational analyses. All of the co-authors wrote and edited the manuscript.

Additional Information

Supplementary information accompany this paper at www.nature.com/naturechemicalbiology/. Reprints and permission information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions/.

References

- 1.Isaacs ED, Shukla A, Platzman PM, Barbiellini DR, Tulk CA. Covalency of the hydrogen bond in ice: A direct x-ray measurement. Phys Rev Lett. 1999;82:600–603. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinhold F, Landis CR. Valency and Bonding: A Natural Bond Orbital Donor–Acceptor Perspective. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinhold F. Resonance character of hydrogen-bonding interactions in water and other H-bonded species. Adv Protein Chem. 2005;72:121–155. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)72005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khaliullin RZ, Cobar EA, Lochan RC, Bell AT, Head-Gordon M. Unravelling the origin of intermolecular interactions using absolutely localized molecular orbitals. J Phys Chem A. 2007;111:8753–8765. doi: 10.1021/jp073685z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirsky AE, Pauling L. On the structure of native, denatured, and coagulated proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1936;22:439–447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.22.7.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray HB. Electrons and Chemical Bonding. W. A. Benjamin; New York: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raber DJ, Raber NK, Chandrasekhar J, Scheleyer PvR. Geometries and energies of complexes between formaldehyde and first- and second-row cations. A theoretical study. Inorg Chem. 1984;23:4076–4080. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laing M. No rabbit ears on water. J Chem Educ. 1987;64:124–128. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pauling L, Corey RB, Branson HR. The structure of proteins: Two hydrogen-bonded helical configurations of the polypeptide chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1951;37:205–211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.37.4.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeRider ML, et al. Collagen stability: Insights from NMR spectroscopic and hybrid density functional computational investigations of the effect of electronegative substituents on prolyl ring conformations. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2497–2505. doi: 10.1021/ja0166904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinderaker MP, Raines RT. An electronic effect on protein structure. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1188–1194. doi: 10.1110/ps.0241903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horng JC, Raines RT. Stereoelectronic effects on polyproline conformation. Protein Sci. 2006;15:74–83. doi: 10.1110/ps.051779806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hodges JA, Raines RT. Energetics of an n→π* interaction that impacts protein structure. Org Lett. 2006;8:4695–4697. doi: 10.1021/ol061569t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao J, Kelly JW. Toward quantification of protein backbone–backbone hydrogen bonding energies: An energetic analysis of an amide-to-ester mutation in an α-helix within a protein. Protein Sci. 2008;17:1096–1101. doi: 10.1110/ps.083439708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shoulders MD, Raines RT. Collagen structure and stability. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:929–958. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.032207.120833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choudhary A, Gandla D, Krow GR, Raines RT. Nature of amide carbonyl–carbonyl interactions in proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7244–7246. doi: 10.1021/ja901188y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dai N, Etzkorn FA. Cis–trans proline isomerization effects on collagen triple-helix stability are limited. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:13728–13732. doi: 10.1021/ja904177k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorske BC, Stringer JR, Bastian BL, Fowler SA, Blackwell HE. New strategies for the design of folded peptoids revealed by a survey of noncovalent interactions in model systems. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16555–16567. doi: 10.1021/ja907184g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pal TK, Sankararamakrishnan R. Quantum chemical investigations on intraresidue carbonyl–carbonyl contacts in aspartates of high-resolution protein structures. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:1038–1049. doi: 10.1021/jp909339r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jakobsche CE, Choudhary A, Raines RT, Miller SJ. n→π* Interaction and n)(π Pauli repulsion are antagonistic for protein stability. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6651–6653. doi: 10.1021/ja100931y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berman H, Henrick K, Nakamura H, Markley JL. The worldwide Protein Data Bank (wwPDB): Ensuring a single, uniform archive of PDB data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D301–D303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahan SD, Ireton GC, Knoeber C, Stoddard BL, Black ME. Random mutagenesis and selection of Escherichia coli cytosine deaminase for cancer gene therapy. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2004;17:625–633. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzh074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Y, Morais-Cabral JH, Kaufman A, MacKinnon R. Chemistry of ion coordination and hydration revealed by a K+ channel–Fab complex at 2.0 Å resolution. Nature. 2001;414:43–48. doi: 10.1038/35102009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esposito L, Vitagliano L, Zagari A, Mazzarella L. Pyramidalization of backbone carbonyl carbon atoms in proteins. Protein Sci. 2000;9:2038–2042. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lario PI, Vrielink A. Atomic resolution density maps reveal secondary structure dependent differences in electronic distribution. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:12787–12794. doi: 10.1021/ja0289954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makhatadze GI. Peptide solvation and H-bonds. Adv Protein Chem. 2006;72:199–226. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)72008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang AS, Honig B. Free energy determinants of secondary structure formation: I. α-Helices. J Mol Biol. 1995;252:351–365. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka S, Scheraga HA. Statistical mechanical treatment of protein conformation. I. Conformational properties of aminoacids in proteins. Macromolecules. 1976;9:142–159. doi: 10.1021/ma60049a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toniolo C, Bonora GM, Mutter M, Pillai VNR. Linear oligopeptides. 78 The effect of the insertion of a proline residue on the solution conformation of host peptides. Makromol Chem. 1981;182:2007–2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altmann KH, Wojcik J, Vasquez M, Scheraga HA. Helix–coil stability constants for the naturally occurring amino acids in water. XXIII Proline parameters from random poly(hydroxybutylglutamine–co–L-proline) Biopolymers. 1990;30:107–120. doi: 10.1002/bip.360300112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yun RH, Anderson A, Hermans J. Proline in α-helix: Stability and conformations studied by dynamics simulation. Proteins. 1991;10:219–228. doi: 10.1002/prot.340100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venkatachalapathi YV, Balaram P. An incipient 310 helix in Piv–Pro–Pro–Ala-NHMe as a model for peptide folding. Nature. 1979;281:83–84. doi: 10.1038/281083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tobias DJ, Brooks CL., III Thermodynamics and mechanism of α-helix initiation in alanine and valine peptides. Biochemistry. 1991;30:6059–6070. doi: 10.1021/bi00238a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheinerman FB, Brooks CL., III 310 Helices in peptides and proteins as studied by modified Zimm–Bragg Theory. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:10098–10103. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monticelli L, PTD, Colombo G. Mechanism of helix nucleation and propagation: Microscopic view from microsecond time scale MD simulation. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:20064–20067. doi: 10.1021/jp054729b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richardson JS, Getzoff ED, Richardson DC. The β-bulge: A common small unit of nonrepetitive protein structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:2574–2578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chothia C, Novotny J, Bruccoleri R, Karplus M. Domain association on immunogloblin molecules. The packing of variable domains. J Mol Biol. 1985;186:651–663. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones EY, Davis SJ, Williams AF, Harlos K, Stuart DI. Crystal structure at 2.8 Å resolution of a soluble form of the cell adhesion molecule CD2. Nature. 1992;360:232–239. doi: 10.1038/360232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan AWE, Hutchinson EG, Harris D, Thornton JM. Identification, classification, and analysis of β-bulges in proteins. Protein Sci. 1993;2:1574–1590. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560021004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hutchinson EG, Thornton JM. PROMOTIF—a program to identify and analyze structural motifs in proteins. Protein Sci. 1996;5:212–220. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewis PN, Momany FA, Scheraga HA. Folding of polypeptide chains in proteins: A proposed mechanism for folding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:2293–2297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.9.2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zimmerman SS, Scheraga HA. Local interactions in bends of proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:4126–4129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.10.4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Novotny M, Kleywegt GJ. A survey of left-handed helices in protein structures. J Mol Biol. 2005;347:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farooq A, et al. Solution structure of ERK2 binding domain of MAPK phosphatase MKP-3: Structural insights into MKP-3 activation by ERK2. Mol Cell. 2001;7:387–399. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gray HB, Winkler JR. Electron flow through proteins. Chem Phys Lett. 2009;483:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2009.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frisch MJ, et al. Gaussian 03, Revision C.02. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford, Connecticut, USA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weinhold F. Natural Bond Orbital Methods. In: Schleyer PvR, et al., editors. Encyclopedia of Computational Chemistry. Vol. 3. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, UK: 1998. pp. 1792–1811. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang G, Dunbrack RL. PISCES: A protein sequence culling server. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1589–1591. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kabsch W, Sander C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: Pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stapley BJ, Creamer TP. A survey of left-handed polyproline II helices. Protein Sci. 1999;8:587–595. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.3.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.