Abstract

Context

There has been some suggestion that the fatigue experienced by older cancer patients is more severe than that of younger cohorts; however, there is little empirical evidence to support this claim.

Objectives

The goal of the present study was to determine the differential impact of age and cancer diagnosis on ratings of fatigue using a validated self-report instrument.

Methods

The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue subscale (FACIT-F) consists of 13 items measuring fatigue experience and its impact on daily life, with scores ranging from 0 (severe fatigue) to 52 (no fatigue). Fatigue data were available from the U.S. general population (n = 1075; 51.3% female, 45.9 ± 16.5 yrs) and a sample of mixed-diagnosis cancer patients (n = 738; 64.3% female, 58.7 ± 13.6 yrs). General population participants were recruited using an internet-based survey panel; patients with cancer were recruited from Chicago-area oncology clinics.

Results

On average, the cancer patient group reported more severe fatigue than the general population group (36.9 vs. 46.6; F[1,1797] = 271.95, P < 0.001). There was evidence for increased fatigue with age (F(6,719) = 2.56, p < 0.02) among patients with cancer, but not in the general population (P = 0.06). Furthermore, the group × age interaction was not significant (P = 0.44). Hemoglobin (Hgb) was treated as a covariate for 430 patients with available data; there was no main effect for age in this analysis.

Conclusion

Older adults, whether or not they had a cancer diagnosis, reported more fatigue than younger adults. These differences may be explained, in part, by Hgb level. Future research would be helpful to explore longitudinal changes in fatigue in the general population and to guide fatigue management for the older cancer patient.

Keywords: Fatigue, cancer, assessment, patient-reported outcome, hemoglobin

Introduction

Fatigue is the most prevalent symptom among individuals with cancer and may be due to the disease itself, its treatment, and/or psychosocial variables (1). Depending on the patient population and means of measuring fatigue, prevalence estimates among cancer patients are generally high, ranging from 60 to over 90% (1). Furthermore, in a large sample of patients with advanced cancer who have received chemotherapy, fatigue was spontaneously endorsed and ranked as the most important symptom that should be monitored (2). While common, cancer-related fatigue remains poorly understood (3). Patients may describe their experience of fatigue in terms of being exhausted, tired, weak, or slowed. In clinical practice, fatigue may be neglected or under-detected due to the fact that it is a subjective experience that is assessed by patient self-report. Treatment of cancer-related fatigue is further complicated by its multifactorial clinical manifestations, involving both psychological and physical components.

One common cause of fatigue in the context of cancer is anemia. The decrease in hemoglobin (Hgb) leads to patient weakness, pallor, dyspnea, and fatigue. Given their non-specific nature, symptoms of anemia are often difficult to attribute directly to anemia itself. However, the impact of low Hgb can be far-reaching (4,5). Important heath-related outcomes such as quality of life (QOL) can be enhanced with proper evaluation and treatment of fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms (6), especially for the older adult (7).

There has been some suggestion that the fatigue experienced by older cancer patients is more severe than that of younger cohorts; however, there is little empirical evidence to support this claim. This is especially relevant in the case of elderly who may be more likely to consider fatigue a normal part of the disease course with which they must suffer. In fact, our group has found no effect of age on cancer-related fatigue (CRF), when comparing patients older than 50 to those younger (3). That said, few data are available to guide the assessment and treatment of CRF in older cancer patients. This lack of information is of considerable concern given that CRF can seriously compromise patients’ quality of life and ability to function on a daily basis (8).

Given the general aging of the cancer population, and the importance of addressing fatigue in this population, we conducted a closer examination of the potential impact of age on cancer-related fatigue. Specifically, available cross-sectional datasets were used to investigate whether fatigue varied systematically as a function of both age and diagnosis. We hypothesized that cancer patients would report more fatigue than the general population and that this difference would be more pronounced for the older sample. That is, a statistical interaction between age and diagnosis was expected with respect to fatigue. Hemoglobin values were available for a subset of patients, and it was hypothesized that differences in fatigue may be at least partly explained by this important clinical variable.

Patient and Methods

Sample

Two existing datasets for this cross-sectional, secondary data analysis were utilized. Full details on recruitment of the samples are found in the original publications (3,9–12). Briefly, the first dataset consisted of a large sample (n = 1075) of individuals from the general population, randomly drawn to complete a series of questionnaires from more than 100,000 individuals enrolled in an Internet-based survey panel (9). Data from several mixed-diagnosis cancer samples (3,10–12) comprised the second dataset (n = 738). In this second dataset, patients were recruited from Chicago-area oncology clinics for studies on health-related quality of life. All patients received some treatment for their cancer.

Ethics

Participants provided informed consent prior to data collection. Original data collection and informed consent procedures were approved by the appropriate institutional review board.

Assessments

All participants completed the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue (FACIT-F) subscale.(10) The FACIT-F is a 13-item scale that asks respondents to rate statements regarding their fatigue experience and its impact on their daily life. Sample items include: “I feel fatigued;” “I feel weak all over;” and “I feel listless (washed out).” All items are rated on a 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much) scale. By scoring convention, after appropriate reverse scoring of 11 items, lower scores on the FACIT Fatigue subscale indicate greater levels of fatigue. (A scoring template is available at www.facit.org.) Originally developed for use with cancer patients (9,13), the scale has been successfully tested for use in the general population (3;9) and chronic anemia of aging (7). To enhance the clinical usefulness of the FACIT-F subscale, Cella and colleagues (13) estimated a minimum clinically meaningful difference of 3 points by using both anchor- and distribution-based methods. Additionally, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance ratings were available for all cancer patients and hemoglobin values, obtained within 30 days of fatigue ratings, were available for a subset of 430 cancer patients.

Data Analysis

Sociodemographic and clinical comparisons between the general population and patient groups were conducted using independent samples t-tests or χ2 tests, as appropriate. Analyses of variance (ANOVA) and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to assess differences in fatigue across age categories. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using PASW Statistics 17 (14).

Results

Sample Characteristics

As summarized in Table 1, the general population sample was 45.9 ± 16.6 years old, 51% female, and primarily (84%) Caucasian. When asked to rate their health status on a 1 (“good”) to 5 (“bad”) scale, 56% of the sample responded with either a 1 or 2 rating. Patients were 58.7 ± 13.6 years, 64% female, 88% Caucasian, and 79% self-reported ECOG performance status ratings of 0 or 1 (no symptoms to symptomatic, but ambulatory) (15). Breast (33%) and colorectal (12%) were the most common tumor types. Patients were older (t(1802) = 17.3, P < 0.001) and more likely to be female (χ2(1) = 29.6; P < 0.001), compared to the general population sample.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Summary of Samples

| General Population (n = 1075) | Cancer Sample (n = 738) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (M ± SD) | 45.9 ± 16.6 yrs | 58.7 ± 13.6 years |

| % Female | 51% | 64% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 84.1% | 88.0% |

| African-American | 10.1% | 6.0% |

| Hispanic | 3.0% | 3.0% |

| Other | 2.8% | 3.0% |

| Self-Reported Health Status | ||

| “good” 1 | 19.4% | 37.6% ECOG PSR 0 |

| 2 | 36.5% | 41.6% PSR 1 |

| 3 | 31.0% | 17.0% PSR 2 |

| 4 | 10.7% | 3.8% PSR 3 |

| “bad” 5 | 2.5% | 0.0% PSR 4 |

| FACIT-Fatigue Subscale Score | 46.6 ± 7.2 | 36.9 ± 11.4 |

| Hemoglobin | -- | 12.0 ± 1.9 g/dL |

| Tumor Type | -- | 33.4% breast |

| 11.9% colorectal | ||

| 9.1% NHL | ||

| 7.3% ovarian | ||

| 5.1% prostate | ||

| Cancer Stage | ||

| Stage I | -- | 10.2% |

| Stage II | -- | 24.6% |

| Stage III | -- | 26.9% |

| Stage IV | -- | 19.8% |

Note:

ECOG Performance Status Rating = 0 = fully active without restriction; 4 = completely disabled, no self-care.

Lower scores on the FACIT-F indicate greater levels of fatigue.

Cancer patients reported more severe fatigue than the general population (F(1,1804) = 329.2, P < 0.001).

Fatigue

As expected, cancer patients reported more fatigue (FACIT-Fatigue subscale = 36.9 ± 11.4) than the general population sample (46.6 ± 7.2; F(1, 1804) = 329.2, P < 0.001). This finding was not due to the difference in gender ratios between the samples. While females reported more fatigue than males in the general population sample (t(1057) = 3.7, P < 0.001), males and females reported comparable levels of fatigue (t(724)<1, P > 0.5) in the cancer sample. Additionally, when the entire sample (i.e., patients and general population) was subdivided using a binary age split (<65 vs. ≥65), older individuals reported more fatigue (40.2 ± 11.0) than those less than 65 years old (43.4 ± 10.0; F(1,1797) = 33.9, P < 0.001). Because an age cut-off of 65 is arbitrary, the first age analysis was followed up with a mean comparison of fatigue by age, divided by decade. This analysis confirmed the association of age with fatigue (F(6,1797) = 15.5, P < 0.001). Table 2 presents the mean fatigue scores by decade across the entire sample. Considered independently, diagnosis status and age were associated with increased fatigue, but the age trend becomes more consistent when the two subsamples are combined. Given the relatively low representation of the very young and the very old in our cancer sample, we also tested the association of age separately for each group. In the cancer sample, there was a significant association, F(6, 719) = 2.56, P < 0.02, suggesting an increase in fatigue with age. The association of fatigue with age in the general population sample suggested a non-significant trend, F(6, 1065) = 2.03, P = 0.06.

Table 2.

FACIT-Fatigue Subscale Scores, by Population, Age, and for the Total Sample

| Population | Age Category | n | % | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Population | 18–30 | 18 | 2.5 | 35.5 | 11.7 | 6 | 51 |

| 30–40 | 48 | 6.6 | 37.8 | 11.1 | 11 | 52 | |

| 40–50 | 133 | 18.3 | 36.0 | 11.6 | 7 | 52 | |

| 50–60 | 181 | 24.9 | 37.3 | 11.3 | 3 | 52 | |

| 60–70 | 172 | 23.7 | 38.5 | 11.4 | 3 | 52 | |

| 70–80 | 145 | 20.0 | 36.1 | 10.4 | 7 | 52 | |

| 80+ | 29 | 4.0 | 30.5 | 13.3 | 3 | 52 | |

| Total | 726 | 100.0 | 36.8 | 11.4 | 3 | 52 | |

| General Population | 18–30 | 224 | 20.9 | 46.2 | 7.6 | 15 | 52 |

| 30–40 | 219 | 20.4 | 47.6 | 5.9 | 23 | 52 | |

| 40–50 | 218 | 20.3 | 46.2 | 7.8 | 16 | 52 | |

| 50–60 | 190 | 17.7 | 47.1 | 6.5 | 19 | 52 | |

| 60–70 | 128 | 11.9 | 46.1 | 7.3 | 19 | 52 | |

| 70–80 | 72 | 6.7 | 46.0 | 7.9 | 18 | 52 | |

| 80+ | 21 | 2.0 | 43.4 | 8.6 | 19 | 52 | |

| Total | 1072 | 100.0 | 46.6 | 7.2 | 15 | 52 | |

| Total | 18–30 | 242 | 13.5 | 45.4 | 8.5 | 6 | 52 |

| 30–40 | 267 | 14.8 | 45.8 | 8.1 | 11 | 52 | |

| 40–50 | 351 | 19.5 | 42.3 | 10.6 | 7 | 52 | |

| 50–60 | 371 | 20.6 | 42.3 | 10.4 | 3 | 52 | |

| 60–70 | 300 | 16.7 | 41.8 | 10.6 | 3 | 52 | |

| 70–80 | 217 | 12.1 | 39.4 | 10.7 | 7 | 52 | |

| 80+ | 50 | 2.8 | 35.9 | 13.1 | 3 | 52 | |

| GRAND TOTAL | 1798 | 100.0 | 42.6 | 10.3 | 3 | 52 | |

Note:

Total N does not equal 1813 due to missing data.

FACIT-Fatigue subscale scores have a possible range of 0–52. Lower scores indicate greater levels of fatigue.

A 3-point change on the FACIT-Fatigue subscale has been shown to indicate clinically significant change in fatigue over time (13).

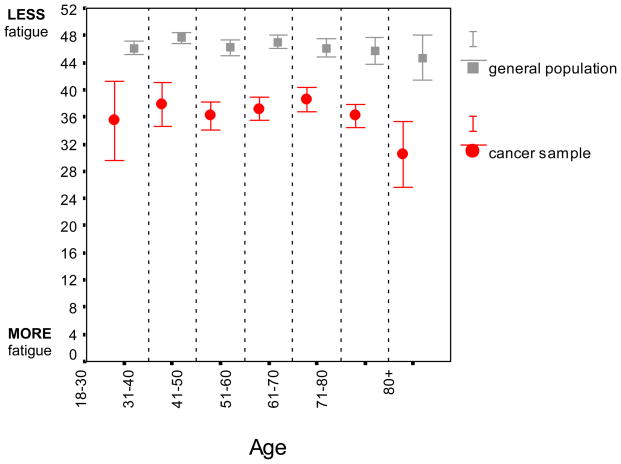

A test of the interaction between sample (i.e. general population vs. cancer sample) and age required a test of both effects simultaneously. Considered conjointly, the main effect for sample (F(1,1797) = 271.9, P < 0.001) and age (F(6,1797) = 3.5, P < 0.01) remained; however, there was no support for a sample - age interaction (F(6,1707) = 0.98, P = 0.44). This lack of statistical interaction suggests that while cancer patients reported more fatigue than the general population, this difference did not increase significantly with age. Across the total sample, results from a regression analysis suggested that with each additional decade, fatigue scores worsened (M ± SE) by 1.27 ± 0.14 points on the FACIT-F (P < 0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Fatigue in the general population and among cancer patients with advancing age.

Bars represent means ± 95% CI. Across both groups, there was evidence for increased fatigue with age (F(6, 1797) = 3.53, P < 0.01) but no group × age interaction (P > 0.25).

Hemoglobin

The potential impact of Hgb on fatigue ratings by age was investigated in the subset of cancer patients with available data (n=430). Of note, those patients with available Hgb values were not different from those patients without these data with respect to age (F(1,730) = 0.001, P = 0.98), sex (χ2(1) = 0.15; P = 0.70), or FACIT-Fatigue subscale scores (F(1,730) = 1.65, P = 0.20).

For those with available Hgb, the mean ± SD values were within normal limits (12.0 ± 1.7 g/dL), and ranged from 7.0 g/dL to 19.3 g/dL. Hgb values were modestly associated with FACIT-Fatigue subscale scores (r = 0.24, P < 0.001), in the expected direction. Men had higher Hgb values (12.4 ± 2.0 g/dL) than women (11.8 ± 1.5 g/dL; t(428) = 3.15, P < 0.005). Interestingly, while there was no direct association of Hgb with age category (F(6,429) = 0.75, P = 0.61), when Hgb was treated as a covariate in an analysis of variance of the effect of age on fatigue ratings, Hgb explained significant variance in fatigue ratings (F(1,426) = 24.15, P < 0.001), but age category (i.e., decade) did not (F(6,426) = 1.63, P = 0.14).

Discussion

The present cross-sectional study is notable in that it is the first to directly assess the statistical interaction between diagnosis and age on fatigue. Based on extant research one might expect no or limited impact of age on cancer-related fatigue (16). Cella and colleagues (3) found that people older than 50 years in the general population reported more fatigue than their younger counterparts on the 13-item FACIT-Fatigue, but found no such age effect in the sample of anemic cancer patients. Similar analyses in other cancer clinical trials have failed to find a substantial effect of age on fatigue- and/or anemia-related quality of life in cancer patients (17,18). In contrast, the present analyses suggest that, as the decades accumulate, ratings of fatigue increase. However, increases in fatigue are not more pronounced for older patients with cancer compared to the general population. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first published analysis that addresses this topic by considering cancer diagnosis and age concurrently.

Across the overall sample of cancer patients and the general population, there is a statistically significant but somewhat modest increase in fatigue with age (1.27 points per decade on the FACIT-F). Evaluation of the cancer and general population subgroups revealed that the increase in fatigue was more evident in the cancer sample. Hemoglobin level appears to be a meaningful covariate and may be one of many factors that account for the age-associated differences in fatigue within the cancer sample.

Low hemoglobin (Hgb) is common in the elderly, and the incidence increases with age. A recent analysis of U.S. national data using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988–1994) suggests that the rate of anemia is 10–11% for individuals over the age of 65 and greater than 20% for individuals over the age of 85 (19). Thus, given that both anemia and cancer are common among the elderly, the question of age-associated fatigue changes is important to consider.

Of course, cancer-related fatigue is not always due to low Hgb (1,20,21), as suggested by the modest correlation between Hgb and FACIT-Fatigue subscale scores in the present analysis. Cancer-related fatigue also may be brought on by the direct effects of the cancer, comorbid medical conditions, psychosocial factors and/or other treatment related side effects (1,22,23) that were not assessed as part of this study. We focused on anemia as a potential explanatory variable in the present analysis because it was available for a significant portion of patients in this secondary data analysis. Additional data are needed to characterize the fatigue of the oldest cancer patients; our own sample was deficient in this age range. It would also be helpful to replicate the present findings in a sample of patients receiving more aggressive treatment regimens, as this would likely have significant impact on patient’s reported fatigue. Although we were limited in terms of potential covariates and our cell sizes for the oldest old, our secondary data analysis was successful in generating hypotheses for future studies. Indeed, there is much research to be done to improve our understanding of how ratings of fatigue change with age.

There remain questions to be answered with respect to changes in fatigue over time and the consequences of fatigue in aging adults. As individuals age, there may be a shift in their report of fatigue, due to some level of accommodation for or acceptance of reduced activity levels (24). Fatigue may also impact the ability to participate in important life activities, which may be associated with inactivity, subsequent loss of muscle tone and weakness, and increased disability (25). A sense of decreased ability to engage in physical activity may also have psychological consequences that should be monitored (26). Certainly, additional research may be useful to explore longitudinal changes in fatigue to guide fatigue management for the older patient with and without cancer.

Acknowledgments

A subset of the data analyzed for this study was collected as part of NIH RO1 CA60068 (PI: David Cella, PhD); supported in part by grant UL1RR025741 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Portions of these findings were presented at the 2008 meeting of the Society for Behavioral Medicine.

Disclosures: Dr. Butt has received grant support from and served as a consultant for Ortho Biotech, and has served as a consultant for Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Cella has received grant support from Ortho Biotech. The other authors have no disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wagner LI, Cella D. Fatigue and cancer: causes, prevalence and treatment approaches. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:822–828. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butt Z, Rosenbloom SK, Abernethy AP, et al. Fatigue is the most important symptom for advanced cancer patients who have had chemotherapy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008;6:448–455. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2008.0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cella D, Lai JS, Chang CH, Peterman A, Slavin M. Fatigue in cancer patients compared with fatigue in the general United States population. Cancer. 2002;94:528–538. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beghe C, Wilson A, Ershler WB. Prevalence and outcomes of anemia in geriatrics: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Med. 2004;116(Suppl 7A):3S–10S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pujade-Lauraine E, Gascon P. The burden of anaemia in patients with cancer. Oncology. 2004;67 (Suppl 1):1–4. doi: 10.1159/000080702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogelzang NJ, Breitbart W, Cella D, et al. Patient, caregiver, and oncologist perceptions of cancer-related fatigue: Results of a tripart assessment survey. The Fatigue Coalition. Semin Hematol. 1997;34:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agnihotri P, Telfer M, Butt Z, et al. Chronic anemia and fatigue in elderly patients: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover exploratory study with epoetin alfa. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1557–1565. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cella D, Kallich J, McDermott A, Xu X. The longitudinal relationship of hemoglobin, fatigue and quality of life in anemic cancer patients: results from five randomized clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:979–986. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cella D, Zagari MJ, Vandoros C, et al. Epoetin alfa treatment results in clinically significant improvements in quality of life in anemic cancer patients when referenced to the general population. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:366–373. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13:63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai JS, Cella D, Dineen K, et al. An item bank was created to improve the measurement of cancer-related fatigue. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai JS, Crane PK, Cella D. Factor analysis techniques for assessing sufficient unidimensionality of cancer related fatigue. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:1179–1190. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cella D, Eton DT, Lai JS, Peterman AH, Merkel DE. Combining anchor and distribution-based methods to derive minimal clinically important differences on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) anemia and fatigue scales. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:547–561. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00529-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.PASW for Windows. Rel 17.02. Chicago, IL: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butt Z, Cella D. Relationship of hemoglobin, fatigue, and quality of life in anemic cancer patients. In: Nowrousian MR, editor. Recombinant human erythropoietin (rhEPO) in clinical oncology: Scientific and clinical aspects of anemia in cancer. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2008. pp. 369–392. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thome B, Dykes AK, Hallberg IR. Quality of life in old people with and without cancer. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:1067–1080. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000031342.11869.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aapro MS, Cella D, Zagari M. Age, anemia, and fatigue. Seminars in Oncology. 2002;29:55–59. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.33534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guralnik JM, Eisenstaedt RS, Ferrucci L, Klein HG, Woodman RC. The prevalence of anemia in persons age 65 and older in the United States: evidence for a high rate of unexplained anemia. Blood. 2004;104:2263–2268. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipman AJ, Lawrence DP. The management of fatigue in cancer patients. Oncology. 2004;18:1527–1534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobsen PB. Assessment of fatigue in cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004:93–97. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mock V, Atkinson A, Barsevick AM, et al. Cancer-related fatigue. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5:1054–1078. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2007.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levy M. Cancer fatigue: a review for psychiatrists. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwartz CE, Bode R, Repucci N, et al. The clinical significance of adaptation to changing health: a meta-analysis of response shift. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:1533–1550. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown LF, Kroenke K. Cancer-related fatigue and its associations with depression and anxiety: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:440–447. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.5.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]