Abstract

Late childhood and early adolescence represent a critical transition in the developmental and academic trajectory of youth, a time in which there is an upsurge in academic disengagement and psychopathology. PAR projects that can promote youth’s sense of meaningful engagement in school and a sense of efficacy and mattering can be particularly powerful given the challenges of this developmental stage. In the present study, we draw on data from our own collaborative implementation of PAR projects in secondary schools to consider two central questions: (1) How do features of middle school settings and the developmental characteristics of the youth promote or inhibit the processes, outcomes, and sustainability of the PAR endeavor? and (2) How can the broad principles and concepts of PAR be effectively translated into specific intervention activities in schools, both within and outside of the classroom? In particular, we discuss a participatory research project conducted with 6th and 7th graders at an urban middle school as a means of highlighting the opportunities, constraints, and lessons learned in our efforts to contribute to the high-quality implementation and evaluation of PAR in diverse urban public schools.

Keywords: Participatory action research, Middle school, Children, Adolescents

Participatory Action Research (PAR) can be broadly characterized as a “theoretical standpoint and collaborative methodology that is designed to ensure that those who are affected by the research project have a voice in that project” (Langhout and Thomas, this issue, p. xx). With longstanding practice in community psychology, public health, adult education, and international development as a means of engaging marginalized populations in projects that address conditions of oppression, PAR approaches are becoming more common in other fields such as youth development. Other terminologies are used across disciplines, such as community-based participatory research (CBPR) in public health, Freireian models in adult education, and youth-led participatory research in youth development (Checkoway et al. 2003; Freire 1970; Ginwright et al. 2006; Israel et al. 1994, 2003; London et al. 2003; Minkler and Wallerstein 2003; Schensul et al. 2004).

Common across these approaches is a focus on engaging in a cooperative, iterative process of research and action in which non-professional community members are trained as researchers and change agents, and power over decisions affecting all phases of the research and action are shared equitably among the partners in the collaboration (Israel et al. 1994, 2003). This process intends to provide opportunities for (typically disenfranchised) community members to work together to solve problems of concern to them, develop relevant skills, increase their understanding of their sociopolitical environment, and create mutual support systems (Israel et al. 1994, 2003; Zimmerman 1995).

PAR with Youth: Core Principles

There has been recent attention to PAR as a promising practice in the youth development field. The majority of case reports and other literature have focused on the involvement of youth as evaluators or co-evaluators of after-school and other programs intended to serve youth (Checkoway et al. 2003; Checkoway and Richards-Schuster 2004; Holden et al. 2004; London et al. 2003; Suleiman et al. 2006). There has also been growth in efforts to promote youth “voice” and engagement in improving schools, particularly with youth whose families and communities are politically marginalized due to racism and poverty (Cammarota and Fine 2007; Cargo et al. 2003; Kirshner 2007; Mediratta et al. 2008; Mitra 2004; Morrell 2007; Nieto 1996; Schensul et al. 2004; Shor 1996). The principles of PAR with youth parallel those for adults, with some variation to reflect the diminished power of youth in adult-supervised settings. Given the heavy skill demands of research and advocacy, a major degree of “scaffolding” and alliance-building with adults is expected to occur for youth in the PAR process (Larson et al. 2005; Vygotsky 1978).

Core processes of youth PAR involve the training of young people to identify major concerns in their schools and communities, conduct research to understand the nature of the problems, and take leadership in influencing policies and decisions to enhance the conditions in which they live (London et al. 2003). Key features include an emphasis on promoting youth’s sense of ownership and control over the process, and promoting the social and political engagement of youth and their allies to help address problems identified in the research.

PAR and Schools as Settings for Youth Development

Schools are a critical setting for child development, and are intricately related to key developmental milestones in late childhood and adolescence, including academic achievement, peer relationships, pro-social conduct, and involvement in athletics and clubs (Eccles and Roeser 2003; Masten and Coatsworth 1998). Since the early 20th century, theorists and researchers have made cogent critiques regarding the shortcomings of U.S. schools as contexts for the development of children as learners, thinkers, and members of a democratic society (Dewey 1938/1997; Kozol 1991; Sarason 1996; Weinstein 2002a). As Sarason observed, the typical classroom is one in which teachers rather than students ask questions, adults are rendered “insensitive to what their [children’s] interests, concerns and questions are…and children are viewed as incapable of self-regulation” (Sarason 1996, p. 363). These features of school culture and teacher practices have proven highly resistant to change in public schools, despite the efforts of educational reform movements.

Recent analyses of schools have also emerged from the growing field of youth development. With the goal of informing the practices of school and other youth-serving organizations, reviews of the child development literature have identified the qualities of settings—and the types of transactions between youth and their environments—that are associated with positive development (Eccles and Gootman 2002; Granger 2002). These dimensions are summarized in terms of physical and psychological safety, appropriate structure, supportive relationships, opportunities to belong, positive social norms, support for efficacy and mattering, opportunities for skill building, and the integration of family, school, and community efforts.

As evident from the above discussion, conducting PAR with youth in schools is a process that could potentially target virtually all of the setting-level features that have been linked with healthier development. PAR most explicitly addresses the dimensions of opportunities for developmentally-appropriate and meaningful youth participation, support for efficacy and mattering, the development of relevant skills; and supportive relationships. Examined in light of Sarason’s critique of typical classrooms, the PAR process is clearly counter-cultural insofar as it is fundamentally about student-led inquiry, the valuing of students’ concerns and expertise, and the opening up of opportunities for students to take on tasks and roles that involve self-regulation as well as participation in governance.

Although PAR presents both developmental opportunities and challenges to school culture in any traditional school environment, we submit that this is particularly the case in middle school settings. There is extensive literature establishing that the transition to middle school in late childhood and early adolescence is a crucial period in the trajectory of intellectual and psychosocial development. This period of development has been associated with reductions in academic motivation and achievement (Eccles et al. 1993; Simmons 1987) as well as increases in depression and other psychological problems (Compas et al. 1997; Galaif 2007). The theoretical and empirical work of Eccles and colleagues provides support for the “developmental mismatch” hypothesis—that is, that at least some proportion of the problems in motivation and engagement in school that emerge in early adolescence may be attributable to poor person-environment fit for children at the transition to middle school or junior high (Eccles et al. 1993). Although older children and young adolescents demonstrate growing capacity and desire for autonomy, longitudinal research indicates that youth perceive fewer opportunities to exercise autonomy and participate in making decisions and rules in junior high than they did in elementary schools (Midgley and Feldlaufer 1987). Further, there is evidence that appropriate levels of decision-making and control are particularly salient for motivation and learning in adolescence (Eccles et al. 1993).

The literature on identity formation in childhood and adolescence highlights the importance of a sense of purpose (Damon 2003), and the role of responsibility and service for helping to foster a sense of moral identity (Youniss and Yates 1997). Theoretical frameworks that specifically consider the identity development of youth of color highlight the importance of social position, racism and discrimination, and the influence of their immediate environments (García Coll et al. 1996) as well as youth’s appraisals of themselves and of the risk and protective factors that affect their life trajectories (Spencer et al. 1997; Spencer et al. 2003). PAR’s emphasis on engaging marginalized groups in research and action as a means of achieving social justice and equity goals enhances the potential developmental relevance of PAR processes for ethnic minority youth. PAR processes that involve youth of color in analyzing and having an impact on the social, economic, and political conditions that shape their schools and communities provide key developmental opportunities for youth to appraise themselves as leaders with a meaningful sense of purpose (Damon 2003; Spencer et al. 2003) as opposed to internalizing the negative stereotypes held by others (Cahill et al. 2008). Further, PAR processes should push youth beyond individual-level explanations of problems faced by communities of color to investigate broader explanatory factors, thereby influencing their appraisal of risk and protective factors.

Thus, in our view, middle schools appear to be settings that could benefit from PAR interventions to help reduce the “developmental mismatch” and promote positive identity development for diverse youth. However, in light of extensive evidence for the difficulties in enacting meaningful changes in schools as organizations (Evans 1996; Sarason 1996), we would expect to encounter significant challenges to successfully implementing and sustaining PAR efforts in such settings.

Operationalization of PAR in School Settings

As discussed above, there is extensive theory that broadly informs PAR and other empowerment-oriented interventions (Freire 1994; Zimmerman 1995) and a rich theoretical and empirical literature on the social ecology of schools (Sarason 1996; Trickett and Todd 1972; Weinstein 2002a). There is a small but growing field of research on PAR projects implemented with young people in after-school or summer “institute” settings, some of which explicitly involve youth in research and advocacy to improve their schools (Morrell 2007; Wilson et al. 2007) or to address health, social justice, or employment issues that are relevant to their school experiences (Cammarota and Fine 2007; Wallerstein et al. 2004). This existing literature has presented curricula, documented meaningful narratives about the value of YPAR for the youth, adult collaborators, and communities, discussed challenges involved in implementing YPAR given the diverse capacities it demands for youth and adult facilitators, and provided initial evaluation of outcomes for individual participants (Berg et al. 2009; Wallerstein et al. 2004).

The present study builds on and provides a unique contribution to this literature by specifically considering the integration of PAR into the social ecology of classrooms and schools during the “regular” school day. Here, we draw on data from our own collaborative implementation of PAR projects in secondary schools to consider two central questions: (1) How do features of middle school settings and the developmental characteristics of the youth promote or inhibit the processes, outcomes, and sustainability of the PAR endeavor? and (2) How can the broad principles and concepts of PAR be effectively translated into key processes to guide intervention activities in schools, both within and outside of the classroom?

In section “PAR in an Urban Middle School”, as a means of illustrating key opportunities and challenges regarding the implementation of PAR with youth in school settings, we discuss a participatory action research (PAR) project conducted with 6th and 7th graders at an urban middle school (“Tubman”).1 This project represented the initial year in a multi-year effort involving the collaboration of the school staff, students, staff of a community-based organization, and a university research team. In the “Discussion”, building on the existing literature and our own research, we delineate a set of core processes of PAR interventions in schools that we are currently using to assess our work and offer as a potential contribution to this growing field. We then examine the strengths and weaknesses of the Tubman middle school project through the lens of this process framework, and discuss how our implementation and evaluation of our school-based PAR projects has evolved as a result of this early work.

PAR in an Urban Middle School

Overview of Project

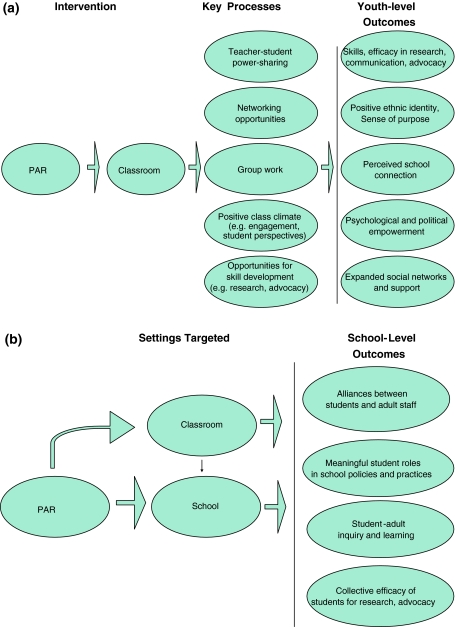

The project discussed here was conducted at “Tubman,” a majority-Latino middle school located in a high-SES urban neighborhood in the San Francisco Bay Area. Tubman is in the small to medium range of size for the district, with ~500 students in 6th through 8th grades. Two-thirds of the students are economically disadvantaged and one-third is classified by the school district as English language learners. The majority of students who attend the school do not live in the surrounding neighborhood. The intended outcomes of the PAR project, with respect to the school setting, were to establish opportunities for students to participate in school governance and shape school practices, via the sharing of research-based recommendations with administrators aimed at improving the school in areas of concern to the students. Other intended school-level effects included improving alliances between students and adult staff, creating opportunities for students and adults to engage together in inquiry about issues relevant to the school and to students, and enhancing the collective efficacy of students to enact thoughtful and high-quality research and advocacy activities. The intended outcomes for students included the strengthening of knowledge and skills regarding research, communication, strategic thinking, collaborative group work, and advocacy, enhanced sense of positive ethnic identity, sense of purpose, and connection to school, and increased motivation to influence the school setting. These targeted outcomes were part of a conceptual model (see Fig. 1a, b) developed by the first author on the basis of the literature on adolescent development, PAR, and psychological empowerment (Eccles and Gootman 2002; London et al. 2003; Rappaport et al. 1984; Zimmerman 2000) as well as prior school-based pilot work conducted by the first author in which students provided their perspective on the benefits of the YPAR process for them.

Fig. 1.

a School-based PAR: youth-level effects model, b School-based PAR: school-level effects model

The project was part of a larger collaborative research effort to develop and evaluate PAR projects at 6 sites; it was undertaken by a partnership primarily consisting of a local community-based organization (CBO), the university-based team led by the 1st author of this paper, and the school site staff (see Ozer et al. 2008 for a discussion of the partnership and capacity-building efforts). The first author, a European American female from a middle-class background, lives near the school and had conducted research at the school several years prior as part of a prior study on stress and mental health.

We focus here on Year 1 of the collaborative project, a pilot phase in the overall study, in which our university-based team consulted with a CBO to support the initial implementation of the PAR project in an elective peer counseling class at Tubman and at five high school sites. After 1 year of providing technical assistance and capacity building efforts directly to the teacher and her CBO-based supervisor at Tubman, the plan was for the PAR project at the school to continue—pending feasibility and teacher interest—with direct support from her CBO supervisor but not the university team. The university team continued to engage in an ongoing consultation and technical assistance relationship with the supervisor and the CBO. The CBO’s goal was to infuse PAR into its existing youth development programs at 20 middle and high school sites in the school district.

Data Collection Methods

The university team (1 European American male graduate student and 1 Latina female undergraduate, both trained in PAR and in observational research methods) made weekly visits to the Tubman classroom throughout Year 1 to provide technical support and help facilitate the PAR project. The research team also documented the process using observational field notes, which were summarized and excerpted to inform this case discussion. As discussed in detail below, a smaller group of 8 female students in the class were selected to participate in an additional series of small group meetings. Consistent with the policy of the school district and the university IRB, the parents/guardians of these students had provided their signed consent. In recruiting students for the group, the first author worked with the teacher to identify consented students that would reflect a range of academic achievement and whom would likely have some exposure to the problems to be addressed by the group. These meetings took place in the empty school cafeteria during their regular class time. These meetings were audio-taped and transcribed; transcriptions were reviewed to create summaries and quotes for this report.

One year after the end of the Year 1 consultation, the first author conducted follow-up interviews with the principal and teacher to learn about activities that were continued at the site after the consultation ended, the potential impact of the process, and challenges encountered. The first author also conducted an interview with the CBO-based supervisor to elicit her insights regarding this project as well as broader lessons learned in supervising teachers conducting PAR projects in 20 middle and high schools. Unfortunately, it was not feasible to conduct follow-up interviews with the students who had participated in the project due to limitations in the initial consenting process that did not allow for re-contacting of the students.

Project Implementation

The ethnically-diverse (Latino, Asian American, African American, and European American) class consisted of 32 students, and met daily as an elective class. The classroom space was very small, providing little space for movement or re-grouping of students in the classroom. This was the teacher’s first year in a regular teaching position.

The curriculum used by the teacher had been adapted by the CBO, using the structure and activities from two published curricula developed by established youth-led PAR organizations (London 2001; Sydlo et al. 2000). The teacher and university team guided the students in mapping the resources and problems of the school and community, and identifying issues of concern for possible research and action. A range of problems were identified by the students, including drugs, pressure to join gangs, school food, and areas in need of physical improvement at the school (e.g., water fountains did not work, no nets on the basketball court, unclean bathrooms). The teacher and university team then facilitated class discussions to assist them in reaching a group decision about which issues to study more in-depth in their research project. The class ultimately chose to focus their efforts on improving school food and the physical plant of the school with the rationale that these issues affect most students and were potentially “winnable.” The class engaged in a photo-voice process (Wang and Burris 1994) to document the problem areas at the school site and develop a storyboard with photographs to share with the principal and other stakeholders. The products of this project were presented to the principal by representatives of the class near the end of the school year. Most of the class members also presented their methodology and findings to a conference sponsored by the CBO in which classes from all 6 schools that were part of the university-CBO-school partnership came together to share their PAR projects.

Challenges in Implementation

Several challenges were encountered in the implementation of this project in Year 1. First, although observations by the research team suggested that students’ cognitive maturity was a good fit for the PAR curriculum insofar as they demonstrated language and critical thinking skills that were “as high or higher than in the high schools,” the students’ social maturity was noted to be uneven:

The challenge here isn’t getting the students engaged, but managing their engagement….There is a marked difference between the boys and girls in the class….the boys are…poking each other, talking over each other, seeking attention; the girls are much calmer and more mature seeming. We may need different strategies for each group. (research memo)

These and other comments in the research memos reflect the challenge confronted in this project of how to transfer appropriate levels of control to the students. Because the observers were also documenting PAR projects in 9th grade high school classrooms, there were comparisons drawn between the conditions in the middle school versus high school classroom:

The vibe in the class is drastically different than in HS classes. The students are more energetic and unfocused…with constant goofing around…it may be difficult to get them to buy into action research. It may be that we have to construct a series of activities that lead them to investigate, but that they aren’t given the level of control of the HS students. (research memo)

The effectiveness of efforts to meaningfully engage less receptive students in this PAR project was undermined by the specific features of limited space and large class size in this urban middle school. The classroom space was inadequate for the class size, which contributed to poor conditions for high-quality discussion, particularly given the teacher’s lack of experience in managing classroom dynamics. To increase engagement and student control over the projects, the PAR curricular activities called for dividing the class into small groups for interactive activities at multiple stages of the project. For example, in this research memo excerpt, a graduate student describes a small group exercise in which students drew a map of their school and what affects their health at school and then reported back to the larger class; the students identified as “difficult” by the teacher are Latino and African-American:

[The teacher] had identified the three boys I was working [with] to all be difficult, and it was hard to get them on task. [Two students] were poking each other with pencils until I got serious and told them I “didn’t want to see it anymore.” [One student] started out drawing the school and after asking them a lot of questions (…”do you think students here are healthy?”) they started to get into it. They got particularly energetic when talking about the food (“Man, the food is nasty. Why do we have to have the same stuff everyday”), the litter (“people leave their trash all outside and that’s why the birds come and then they poop on us”) and the basketball hoops (“The hoop is all bent with no net, no that’s not it, give me the pencil, I’ll draw it.”)…. Everyone finished for the most part and it was time to present…The students had a lot of trouble speaking one at a time. It made it difficult to hear everything. [The teacher]…brought out a little sandbag thing - only the student holding it was supposed to be able to speak. It worked more or less. (research memo)

The small group format with students playing a more active role was generally effective in engaging students who appeared not to pay attention to whole-class activities and discussions. Simultaneous discussions, however, created an even higher noise level in the small space.

The memos above indicate that the research team initially attributed the need for more focused attention in engaging several of the Latino and African-American male students to lower maturity levels among boys. This interpretation did not consider the role of teacher capacity and the classroom physical space, nor did it consider how the broader social ecology of the school with respect to differential expectations and treatment for boys of color may have set the stage for their responses to the curriculum and the research team (see p. 23 for a deeper consideration of these issues). As discussed more fully later, the design of the present study does not enable us to disentangle the influence of students’ development on the implementation of the YPAR project, versus the influence of the classroom and school conditions in which it was embedded.

Adaptation of Implementation

Because the classroom size and environment were not conducive to in-depth discussion, the first author and the classroom teacher came up with a strategy to conduct more intensive work with a subgroup of students in the class. In the second semester of Year 1, the first author initiated additional weekly meetings with a group of 8 girls in the class (7 of whom were Latina) to understand more deeply several problems not being addressed by the whole class, and to come up with recommendations for policies or programs to address these issues.

These small group meetings were, not surprisingly, more fruitful than the discussions in the regular classroom context. Excellent rapport was developed between the first author and the students, and among the students, and there appeared to be substantially less concern with self-presentation in the all-female group than in the regular classroom. The teacher expressed to the first author that the students enjoyed having a group for only girls, and they appeared to relish the special role of meeting with the first author and being asked their opinions. A side benefit of this approach was that it temporarily relieved the overcrowding in the regular classroom for that session. Early on in the meetings, the first author shared that she also lived in the neighborhood and was a parent of a child in the public school system. Several of the students responded to this information by expressing surprise that a resident of the surrounding neighborhood would be interested in the students at the school; one said, “I thought that all of the people in the neighborhood hated us.” Class, ethnic, and language issues were raised at other times, most notably when the girls were discussing family relationships and several shared their view, learned from TV, that all “White people were rich” and that “White families always sit down and eat dinner together,” unlike their own families. Almost all of the students were bilingual, as is the first author, and there was some discussion about the value of both languages in the group that was prompted by some exchanges in Spanish by group members.

The small group meetings focused on several mental and physical health issues that had been identified as problems by students in the issue selection phase in the larger class project, but were not studied in the photo-voice project because of their complexity. For each issue, the first author facilitated the students’ mapping of “root” causes in which they used the metaphor of a tree to name and depict the sources of the problem (the “leaves”) in terms of factors on the level of the individual, family, school, community, and society. The first author then assisted the students in identifying and reflecting on existing efforts to address it, and in generating ideas for suggested improvement or novel interventions to address it further. These students continued to participate in the full-class photo-voice project on the days that they were not in the small group. The topics considered by the small group included the perceived pressure to join gangs for some Latino students at the school, substance use, and family conflict. Gangs and substance use were the issues that generated the most engagement and interest on the part of the students; we discuss the gang issue below to illustrate the process and the type of insights and recommendations that emerged from the group.

Gang Membership

Pressure to join gangs or “claim colors” in gang rivalries in their neighborhoods were perceived as highly relevant to the group. Multiple girls reported that relatives or friends had claimed colors or had been pressured to join a gang. Although the school had a strict dress code to prevent the wearing of gang-related colors, students reported that they noticed peers starting to claim colors by “small things…a hair tie or something, or shoes, or belt. I think the belt shows more, or carrying a bandana out of your pocket.”

Students discussed what they understood to be the root causes of gang involvement, as well as additional conditions that contributed to the problem. They cited a need for protection for recent immigrant youth, lack of awareness of how hard it is to get out of a gang, and lack of connection at home and school as major factors:

They don’t feel special at home or at school – and the gangs make people feel special and important…Sometimes parents tell them that they aren’t going to do much in their life, that they don’t have much to look forward to.

Students also noted that, for a small number of youth, adult family members are already gang-affiliated and membership is a natural thing: If “part of your family is in a gang – they think it’s in their blood.” One of the lower-achieving students provided her view as to how the Latino honor roll, a school practice designed to encourage the academic engagement and success of Latino students, actually undermined the motivation of Latino students who were below the cut-off, saying that “you feel like a moron” if you don’t make the list.

Recommendations

As indicated above, students identified a lack of meaningful connection to school and families as enhancing the perceived benefits of gang involvement, although they also acknowledged that even students who did have good ties to home and school might feel the need to claim colors because of pressure and threats. They expressed that hearing messages from adults about not joining gangs might actually make gangs seem more appealing because of “reverse psychology” and some youth’s desire to do the opposite of what adults tell them to do. They therefore suggested that educational experiences that entailed hearing from young adults in their late teens or early ‘20’s who “have gone through this kind of thing” and can talk about how hard it was to get out of gangs would be a good program for the school. The group also suggested ideas for rewarding students for academic improvement, even if they do not make the honor roll, so that they feel that this effort is acknowledged.

Having young adults to talk to at the school was a theme that cut across the group’s recommendations for gang prevention, substance abuse, and other areas. They reported that, despite the presence of a school counselor, students feel that “they have no one to talk to about their problems.” Two main concerns about talking with teachers or counselors were raised: that the adult will tell their parents, because they think it will be for their own good, “but this could make it a lot worse.” The second reason that they expressed is that the counselor and many of the teachers “wouldn’t really understand because they are too old,” and that they need a younger person whom they feel would really understand what they are going through.

Principal Meeting

This group, accompanied by the first author, met with the principal near the end of the school year to present their analyses of the issues facing students at Tubman and to share their suggested recommendations for addressing these problems. The principal listened attentively to the students’ presentation and expressed appreciation for their feedback; he suggested that there be future meetings in which he could hear the perspectives of students. The students were initially nervous in their presentation but were able to articulate their views and participate in back-and-forth exchanges with the principal that were respectful and substantive. Afterwards, they appeared excited and reported being pleased with having had the opportunity to talk with the principal in this way.

Follow-Up: Reflections on Longer-Term Impact and Sustainability

Year 1 PAR Project

Interviews with the teacher, principal, and supervisor (all European American) conducted 1 year after the end of the university consultation in Year 1 of the project suggested several insights regarding PAR at Tubman. The teacher, who had fortunately moved to a much larger classroom space, reported that she had continued with the PAR efforts in the subsequent year by initiating a photo-voice project with her new cohort of students. The new project was not directly based on the work of the prior year’s students but instead originated with the new cohort. She enthusiastically discussed plans to engage students in film as well as photography as part of their photo-voice project in her next cohort. She continued to engage youth in peer education and conflict resolution efforts at the school through the regular curriculum, although she did not articulate if or how the photo-voice project informed these educational and service efforts. After the Year 1 project, there was no follow up between the principal and teacher to define or implement specific objectives raised in his prior meeting with the students. Based on our interview and the teacher’s planned curriculum, it appears to us that the teacher viewed photo-voice as a valuable tool for promoting the critical thinking and skills of students, but that the potential of PAR for increasing the participation of students in addressing concerns and improving the school was either not understood or was not a priority given limited resources and competing demands.

The principal, in his follow-up interview, reported that several of the problems that the students had identified in the Year 1 PAR project had improved. He attributed these improvements, however, not to suggestions made by the students but rather to broader efforts to improve school safety and climate across the district and at the school: “Back then it was pretty rough…now…there are no hallways with garbage, the climate has changed. We still do have a lot of trash outside after lunch, and other problems…getting high is a problem.” In Year 2, the school had initiated a district-wide program to improve school climate that involved the training of students as peer leaders, but, according to the principal, it was difficult to sustain because the 8th graders were trained in the Spring just before graduation and then “moved on.” He reported being unaware that the photo-voice project had continued beyond Year 1. Despite the interest he had expressed earlier about having more regular meetings with students like the one in Year 1 with the PAR group, no additional meetings had occurred.

Although he observed that many middle school students are not as comfortable as high school students with “getting serious” in talking with adults, he expressed optimism about the PAR process as providing a formal means of student participation beyond the daily conversations that he has with students as a hands-on middle school principal with a regular physical presence at the site: “I see value in student voice, and that adults are needed to structure the conversation, to express what it is that needs improvement. For students to think and speak like they are growing up. I think it can have an impact here, but hasn’t really yet.” Drug use and “tagging” (graffiti using writing and symbols) were two areas in which the principal expressed that he could benefit from PAR-generated data and recommendations:

Substance use is a big area. I would like to know the what and the when. When I talk to students this age about ‘why,” the why isn’t too clear. Maybe using it as an escape from a bad home life, or from no home life. But to have them talk truthfully about this… Another area that I really don’t understand why is tagging. It has zero redeeming value aesthetically – it’s not graffiti – there is no pretense to art. I see it as vandalism. And when I find out who it is sometimes, it’s like, “they did all that?” It’s almost like it’s random who did it.

Discussion

We see several conditions illuminated at Tubman and at other sites that likely influenced the impact and sustainability of PAR, and that may be informative for the conceptualization and implementation of PAR in other school settings. Below, we discuss several features of the school setting that have a bearing on the PAR process for young people and their adult allies in schools, including: constraints on student autonomy, the academic calendar, the size and social network of the adults at the school, and the resources—physical, financial, and time—for non-academic classes. Although these features would be expected to influence the implementation of any school-based intervention, our discussion highlights the “innovation-specific” (Wandersman et al. 2008) salience of these conditions for the diffusion of PAR in schools because of its emphasis on research and action intended to make change and disrupt the status quo (Ozer et al. 2008). Following our consideration of PAR within the social ecology of the Tubman case, we draw on the existing literature and our experiences to propose a set of key processes for the implementation of PAR in schools, examine the Tubman experience in light of these key processes, and propose next steps for research and practice.

Constraints of Existing School Climate and Culture

As noted earlier, middle schools have generally been noted for their emphasis on behavioral control, adult-driven inquiry, and the lack of opportunities for youth to exercise developmentally-appropriate levels of autonomy. Implementing PAR with youth in this context is intended to address these conditions by providing youth-driven inquiry and the opening up of meaningful opportunities for youth to influence school policies and practices. There is a risk, however, that PAR projects within middle school settings will instead reinforce or replicate the “adultist” power dynamics that they are trying to address. In the Tubman example, the PAR project was implemented as part of an elective class that students theoretically “chose” to take; when they chose the class however, it was not clear to them that they would be conducting PAR. Even when they agreed to participate in the PAR project, it is likely that they did not fully understand what it would entail, and it would be difficult to change their class schedule mid-semester. Thus, although many students expressed enthusiasm for working to improve the school via the PAR project, the Tubman project—like other classroom-based PAR implementations that do not select a small group of motivated youth—faced the challenge of engaging students who were not fully invested in the project.2

Classroom observations suggested that the primary challenges to eliciting the active participation of some students—primarily boys of color—appeared to center on general issues of classroom engagement than objections to the PAR process itself. That is, observations of students who appeared to resist participation in the class activities at various times suggested that they became motivated once they were able to focus on the task at hand. There is extensive evidence for the differential expectations for and treatment of youth in color, particularly males, in U.S. schools (Gregory and Weinstein 2008; Skiba et al. 2002; Weinstein 2002b). Clearly, PAR projects must be differentiated from typical classroom relationships and curricula to avoid “business as usual” interactions and role demands from teachers and students alike.

As noted earlier, most of the adults directly involved in the project were from European American backgrounds; nearly all of the students were from ethnic minority backgrounds with a high proportion of Latino youth. It is possible that these differences, which roughly mirror the general demographics of the adults and youth in the school district, may have set the stage for replication of regular classroom dynamics for some students of color who were already experiencing disconnection and disinvestment from classroom activities. Working with students in smaller groups both within and outside of the classroom, however, at times enabled the Tubman project to create interactions that disrupted the typical pattern of engagement and offered opportunities for lower-achieving students to express themselves and contribute meaningfully to the larger project. These small group activities set the stage for peer-to-peer discussion and learning as opposed to questions and answers from the adult teacher.

Academic Policies and Structures

Although lack of time is likely an issue for nearly every PAR project, whether conducted with adult community members or youth, the academic calendar and competing demands represent formidable challenges for school-based PAR. Unlike adult-led PAR and some youth-led PAR projects enacted in afterschool or other CBO settings, projects implemented in schools must operate within the hard deadlines and “black-out periods” of the academic calendar. As noted above, competing interests are particularly strong in schools that are under pressure to improve standardized test scores, where all instructional time must be mapped onto specific state standards. Although the inquiry methods and communication skills integral to PAR curricula likely strengthened learning of basic standards, the PAR process in the elective class at Tubman and other sites was not organized around state learning standards. An additional challenge inherent in the academic structure involves limitations in working with the same cohort over time. Although re-engaging students who have not graduated is possible (unlike an afterschool program, attendance is not optional), students’ scheduling limitations may not permit them to re-enroll in the same elective class. This is particularly true for academically underperforming students with limited opportunities for electives.

Conducting PAR projects in after-school youth development programs or other community-based organizations rather than during the school day is an alternative that carries with it potential benefits and disadvantages. On the positive side, PAR projects implemented in afterschool settings likely benefit from greater freedom from the demands of instructional time (if not of homework completion) and from having longer blocks of time to conduct the work. In addition, an organization that continues to work with youth over several years can have greater continuity of effort over time. This structure can potentially minimize the challenges faced by the teacher at Tubman and at other school sites regarding how to promote the sense of “ownership” for the PAR process of new cohorts of youth while not abandoning the follow-up activities needed to turn the previous cohort’s work into actual change (Ozer et al. 2008).

PAR projects located in after-school or CBO settings are likely to work with a selected group of students that may be less representative of the school. If the focus of the PAR effort is on change within the school, the project will be limited by a more restricted perspective on the school site (although this can potentially be addressed via research conducted by the youth with representative samples of students at the school). PAR programs with self-selected youth—as is the case in the overwhelming majority of programs studied in the existing literature—will also encounter challenges in quantitative evaluations of the impact of PAR on their youth participants because of selection bias.

Size and Social Network of School

Tubman is a relatively small school, and the students benefited from access to the principal; he was frequently observed by our team to be interacting with students in the hallways and outside of the school immediately after the school day. In considering the implementation of PAR across 20 district sites, the CBO supervisor further emphasized the size of the school as a critical factor in terms of “what you can pull off” in middle school:

The smaller the middle school, the more likely you are to actually do something.

They are tighter communities – the teachers know each other – it’s easier to get the access you might want. The only way a small school isn’t an advantage is if students want structural change. Small schools don’t have much capacity for that – for example, if they come up with wanting more electives. At small schools, there is less flexibility on big issues than in big schools. But middle school projects don’t tend to focus on structural issues. At a big middle school, there is such a focus on managing the behavior of students, that they aren’t that into changes to the system, they are less open to it…and they don’t want students in the hallways doing action research.

Another key factor cited by the supervisor beyond the size of the school was the existence of a group of teachers who were already interested in issues like school climate. Because students “need a lot of adult support,” this gives the students a committee or group whom they could immediately identify as potential allies. There was no such group at Tubman that was identified by the teacher in Year 1. This would have provided an excellent resource for the students and the teacher to engage other stakeholders, hear their perspectives, strategize about how to bring about desired changes, and provide continuity of effort from 1 year to the next.

The social ties and power of the specific teacher or other adult who facilitates the PAR process can shape it in several ways. First, elective teachers (like the teacher at Tubman) may be more isolated and lack a department of colleagues and potential allies that could help create receptive conditions for the PAR project. This would be expected to be a particular challenge for a new teacher, although prior research on the social organization of schools indicates that even an experienced teacher may have few opportunities to collaborate or exchange ideas with other teachers at the same site (Little and McLaughlin 1993; Lortie 1975). Second, as discussed in detail below, a teacher of an elective subject may be more likely to have a tenuous job at some school sites. Job insecurity can undermine long-range planning from 1 year to the next. It can also create concerns for teachers that they might experience negative repercussions if the students raise politically-sensitive issues in their PAR project.

The size and social network of schools would be expected to be relevant conditions that may influence the implementation of any school-based intervention; however, PAR’s focus on increasing the power of youth in shaping school conditions, policies, and practices means that alliances with other stakeholders in the school and community and the capacity to sustain efforts over time are particularly crucial. Students engaging in PAR projects that seek to make changes in schools are operating with limited power in a politically-sensitive environment; forming alliances with more powerful stakeholders such as teachers and administrators and getting them “bought in” early on thus improves the likelihood of having a positive impact.

Space for “Non-Academic” Activities

Although conducting PAR via an elective class already focused on youth development was an excellent fit and enabled most of class time to be devoted to the PAR project, it also created challenges in follow-through because of uncertain funding for electives at the case report site and other schools in this under-resourced urban district. At Tubman, there were ongoing negotiations about the role and resources of the elective peer resources program at the site. With the teacher and her supervisor focused on the role and sustainability of the basic program after Year 1, there was less time and focus available to promote the sustainability and impact of the PAR project. According to the supervisor, the issue of program stability is highly salient in determining the scope of work across their 10 middle school sites in the district:

Most middle schools barely have electives. Because of test scores, many students are taking double English and double Math. Every principal is super under the gun to deliver test scores. What is possible [in a PAR project] depends on if the school has turned it around or not. Very little is possible with declining enrollment and flat test scores as these schools are shut down for weeks before the test.

Developmental Considerations

Student Development

How did the developmental level of the youth in our project influence the PAR process, and how was the process adapted to respond to these developmental issues? Uneven social maturity of the students, particularly the boys, was noted in our team’s observations of the Tubman classroom in Year 1. This factor represented a challenge in engaging the class in the PAR curriculum, although the inadequate physical space and the inexperience of the teacher also played contributing roles. The combination of these factors was primarily responded to by creating more structure in the regular class and also by creating the additional small group meetings. The latter format enabled in-depth exchange in a quiet place, with sufficient structure to develop relationships and get beyond the “silliness” that sometimes ensued before the students settled into a more serious discussion. Prior PAR research with slightly younger students than our sample (5th and 6th graders) also identified group dynamics and social maturity as major challenges in implementation, attributing behaviors such as clowning, put-downs, and “silly” responses to questions as part of the early adolescent developmental tasks of identity formation (Wilson et al. 2007). As discussed earlier, some of the challenges in engaging students in PAR activities are probably not solely a function of the developmental level of the students but also of doing PAR in institutional settings in which many students have likely not had access to developmentally-appropriate opportunities to foster students’ capacity to express themselves, think critically, and work together in more mature roles.

In reflecting across the 20 middle and high school sites at which the CBO was conducting some type of PAR project, the supervisor of the Tubman project provided additional insights regarding how the process can respond to the developmental needs of the older child and younger adolescent:

They [middle school students] need to look for more short-term change. It’s hard enough with high school – “that this change might not happen this year” – but in middle school if they don’t see some sort of progress, they are going to lose steam very quickly. Without changing the issue every single time, [we ask]: What are super-concrete actions that all build towards this same thing?… An example from [another middle school] right now is that they did a short survey and found out that racism and stereotypes are a problem. So they are doing three stand-alone events that were all about racism: A lunchtime activity where students talked to those they wouldn’t ordinarily talk to, a multicultural assembly, and an assembly where they put together a game about different people’s experiences.

One way to build on this model, consistent with the iterative nature of PAR, would be to integrate formative evaluation research into the action phase that would enable the youth to assess if their actions actually yielded any benefits. As articulated by the supervisor, a clear advantage of more quickly engaging the students in action steps that are relevant to the problem but do not necessarily involve a change in policies or practices is that they can feel that they are making something happen. This can be problematic, however. Presentations and other events are time-consuming; while they raise awareness, they can create the sense that something is being done about the problem without any meaningful mechanisms for change being implemented (Kirshner 2007).

Teacher Development

It is also important to recognize that adults’ effective implementation of PAR requires substantial experience and support. In contrast to the typical training and skill set of classroom teachers for the instruction of content “standards,” facilitation of PAR requires that classroom teachers share power with students and guide them in a flexible process in which the teacher does not have the answers ahead of time and likely needs ongoing technical assistance regarding research and advocacy activities [please see Ozer et al. (2008) for an extensive consideration of technical support and capacity-building for teachers implementing PAR projects in schools and the California Center for Civic Participation and Youth Development (2004) for more general planning for youth participation.] Other research has noted the considerable challenges in effectively training facilitators to lead PAR projects, although in these cases the facilitators were university students or adult volunteers (Helitzer et al. 2000; Wilson et al. 2007).

Key Processes in School-Based PAR

The existing literature provides an explication of broad principles and several curricula to guide PAR in schools. To our knowledge, however, the field is lacking specific guidelines about how to assess the processes that reflect a high-quality implementation of PAR. We are mindful that PAR projects are inherently flexible and will unfold in differing ways across settings and in response to the particular questions and parameters of each project; however, a common framework may inform practice and guide the assessment of implementation quality necessary for both “continuous improvement” and traditional evaluation efforts of PAR interventions. Our collaborative work in supporting and evaluating PAR at multiple school sites has necessitated assessment of processes that reflect a high-quality operationalization of PAR with students in classroom and school settings. Building on our initial work with Tubman and other sites, our multi-method intervention research utilizes a design that compares the process and outcomes of classrooms engaged in PAR versus classrooms engaged in a direct-service youth development program. This endeavor has further required us to delineate central PAR processes. Our specification of processes build on prior theory and curriculum development in the PAR field (Cargo et al. 2003; Checkoway et al. 2003; Jennings et al. 2006; London 2001; Schensul et al. 2004; Zimmerman 1995); they further reflect dimensions suggested to us by youth in our own research.

Processes that we view as central to PAR in our assessment system are the iterative integration of research and action, the training and practice of research skills, the teacher’s sharing of power with students in the research and action process, and the practice of strategic thinking and strategies for influencing change. Examples of the specific activities we characterize as part of the strategic thinking process include discussion of: root causes to social or health problems, information about how rules or policies are made, how to develop recommendations based in research, and how to develop alliances with various stakeholders.

Processes that promote a high-quality implementation of PAR but are not unique to it include: expansion of the social network of the youth, opportunities and guidance for working in groups to achieve goals, and the development of skills to communicate with other youth and adult stakeholders. All of these processes were reported by the youth participants in our PAR classes as constituting very different experiences from their regular classroom activities, and meaningful aspects of their learning in the PAR process. Class climate has been studied extensively as a key factor in prior educational research; in our evaluation work, we are assessing classroom climate dimensions that we believe facilitate effective implementation of PAR, including the teacher’s emphasis on student perspectives, the teacher’s flexibility regarding classroom projects or structure, and the engagement of the students in the classroom activities (Pianta et al. 2006). Efforts to measure PAR processes through the development of a reliable and valid observational tool are currently in progress.

Looking at the Tubman Project Through Key Processes Framework

The Tubman project experienced mixed success. In light of the challenges faced by this 1st year teacher and her students in Year 1, having this class effectively engage in several phases of the PAR process and make meaningful presentations to their principal and to a conference of high school students were legitimately viewed as major achievements by the students and the adults involved in the project. Further, the teacher continued to implement and value the photo-voice process beyond the initial consultation and the principal remained optimistic about the potential for youth “voice” in the school. No specific improvements in the problems identified by the students or the school site, however, could be attributed to the project.

The Tubman project represents an initial effort that provided multiple lessons useful for the evolution of our work in school-based PAR. With respect to research, students were trained in and practiced photo-voice as a research method and learned about the strengths and limitations of other methods such as surveys and interviews as part of their conference with other students engaged in PAR in the district. With respect to practicing strategies for strategic thinking and influencing change, all students in the Tubman project analyzed the roots of issues of concern to them although the girls’ group received more intensive practice in both analysis of problems and generation of possible solutions. The recommendations of the girls’ group, however, would ideally have been grounded by further research. In terms of students’ sharing of power, the students exercised power in their choice of topics and research methods used; they chose what to photograph and organized their own presentation. As discussed earlier, however, the teacher provided much direction and structure over the classroom activities.

Regarding general processes that support but are not unique to PAR implementation, the Tubman project provided guidance for group work and opportunities for participants to develop their skills in communicating with youth and adult stakeholders. Beyond the meeting with the principal, the first year of the project fell short in its expansion of the participants’ social network and in the building of alliances with school faculty, administrators, and the student body to address the problems identified and promote the implementation of recommended changes in policies or practices. Not surprisingly, ending Year 1 without achieving clear agreements among the principal, teacher, students, and supervisor about specific action steps, a timeline, and accountability for follow-up undermined the potential impact. Finally, the importance of class climate dimensions such as student engagement for effective implementation was highlighted previously.

In retrospect, it is clear that more attention should have been paid to long-range planning and building alliances with teachers and others during the Year 1 initial implementation of the project at Tubman. Long-range planning was challenging to enact, however, for several reasons. First, with the university team in the role of consultant, the issue of planning for next year can be raised (as it was at Tubman), but the power to establish these agreements and commitments remains with the CBO and school sites, who are often in reactive rather than proactive stances when dealing with pressing funding and staffing uncertainties. Second, as evident at Tubman and at other sites where we have worked, the students’ successfully engaging in the PAR process to the point of developing research-driven recommendations and events are legitimately experienced as “wins” for the youth and adults. Given all of the challenges at the sites, it is sometimes difficult for all of those involved in the project to see beyond the specifics of the project to think deeply about sustainable change.

Third, although it would be ideal to engage potential adult allies within and outside of the school for students’ research-driven change efforts earlier in the project, to help pave the way for receptiveness in the action phases, it is our experience that it takes time before students build the skills and confidence to engage with adults in a collegial manner. That is, once students have engaged in the research and have findings to share, they tend to realize the expertise that they are bringing to the table to discuss with adults; these data presentations also help to legitimize their expertise in the eyes of the adults. Thus, preparing the ground with potential adult allies early in the process, before research recommendations are ready, is a key role for the adult facilitators and for youth who feel ready for this; we have also seen effective approaches in our projects in which data-gathering from potential adult allies is used to build relationships and buy-in. Reflections on lessons learned with Tubman and other sites have spurred the CBO and university team to emphasize alliance-building and planning for continuity in the training of teachers, curriculum, and supervision throughout the PAR process.

The kinds of potential allies that youth might want to engage will partially depend on the issue they choose to address; for example, the issue of safety and violence in specific neighborhoods might include meeting with neighborhood and ethnic associations, elected officials, local CBO’s, health care providers, and the police and transportation departments. Issues focused on school equity and conditions would likely engage the site council, school board, PTA, and CBO’s focused on the educational system. Progress on some issues may be aided by these external alliances; in some cases, however, the involvement of outsiders may not be helpful (e.g., involving non-school members in students’ inquiry and action regarding teaching practices or hiring might increase defensiveness and limit constructive collaboration).

Questions Raised and Next Steps

This discussion emphasizes the promise of PAR in middle schools, providing a case example that illustrates multiple opportunities and challenges for PAR practice in middle school. In this case, PAR appeared to be developmentally-appropriate and meaningful for students when basic classroom dynamics were addressed, and was particularly fruitful in a small-group context that facilitated the strengthening of relationships among the youth and with the adult facilitator. Infusing this program into an elective program supervised by a local CBO committed to youth development practice, and providing ongoing technical assistance to the CBO, utilized an existing niche and strengthened existing resources in the school and district. This approach helped the sustainability of PAR efforts because of the CBO’s long-term relationships with the school sites. It also provided an elective “space” for the implementation of PAR in low-performing schools, where implementation in regular academic classes would not have been feasible due to the great demands on instructional time. Elective “spaces,” however, were more tenuous than expected, and uncertain funding for electives undermined longer-term planning.

In our ongoing research, we are studying in-school PAR classes over multiple years at diverse urban sites to help understand the conditions that support effective implementation of this complex intervention (Biglan et al. 2000). Of particular interest is how to strengthen the continuity of effort across semesters and years while allowing for each new cohort to “own” the project, and how youth can impact the climate and governance of their schools despite multiple challenges and competing demands. Our current research further emphasizes the perspectives of the youth participants (as well as adults) on PAR implementation and impact; a limitation of the Tubman project described here was its lack of student perspectives regarding impact. As alluded to earlier, we are working to develop reliable and valid measures of processes and outcomes of school-based PAR with the goal of contributing to research and practice in this growing field. PAR holds tremendous potential for providing the means by which students can initiate inquiry, develop skills, and provide recommendations to improve the developmental quality and fit of middle schools for their development as thinkers and citizens.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a William T. Grant Scholars’ Award to the first author, and by funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Center as part of the Center of Excellence for Youth Violence Prevention (Center for Culture, Immigration and Youth Violence Prevention at UC-Berkeley). The authors express appreciation to Thomas Cook, Tom Weisner, Meredith Minkler, Lawrence Green, and Marc Zimmerman for their consultation; Elizabeth Hubbard, Marieka Schotland, Sarah Jones, and Carmelo Sgarlato for collaboration with the research, and Jeremy Cantor and Jessica Camacho for their assistance in data collection.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

Place and participant names are masked in this article.

The authors acknowledge the contributions of an anonymous reviewer regarding this issue of student autonomy and how the existing expectations for students’ behavior may create challenges for PAR in middle school settings.

References

- Berg M, Coman E, Schensul JJ. Youth action research for prevention: A multi-level intervention designed to increase efficacy and empowerment among urban youth. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;43:345–359. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Ary D, Wagenaar AC. The value of interrupted time-series experiments for community intervention research. Prevention Science. 2000;1(1):31–49. doi: 10.1023/A:1010024016308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill C, Rios-Moore I, Threatts T. Open eyes-different eyes: PAR as a process of personal and social transformation. In: Cammarota J, Fine M, editors. Revolutionizing education: Youth participatory action research in motion. New York: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- California Center for Civic Participation and Youth Development . Youth voices in community design. CA: Sacramento; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cammarota J, Fine M, editors. Revolutionizing education: Youth participatory action research. New York: Routledge; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cargo M, Grams G, Ottoson J, Ward P, Green L. Empowerment as fostering positive youth development and citizenship. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27(Supplement 1):S66–S79. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.1.s1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checkoway B, Richards-Schuster K. Youth participation in evaluation and research as a way of lifting new voices. Children Youth and Environments. 2004;14(2):84–98. [Google Scholar]

- Checkoway, B., Dobbie, D., & Richards-Schuster, K. (2003). Youth participation in community evaluation research as an emerging social movement. Community Youth Development Journal, 4(1), 1–8.

- Compas BE, Oppedisano G, Connor JK, Gerhardt CA, Hinden BR, Achenbaach TM, et al. Gender Differences in depressive symptoms in adolescence: Comparison of national samples of clinically-referred and non-referred youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:617–626. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.65.4.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damon, W. (2003). The development of purpose during adolescence. Applied Developmental Science, 7(3), 119–128.

- Dewey, J. (1938/1997). Experience and education. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

- Eccles JS, Gootman JA. Community programs to promote youth development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Midgley C, Buchanan C, Wigfield A, Reuman D, MacIver D. Development during adolescence: The impact of stage/environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and families. American Psychologist. 1993;48(2):90–101. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.48.2.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. (2003). Schools as developmental contexts In G. R. Adams & M. D. Berzonsky (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of adolescence (pp. 129–148). Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing.

- Evans R. The human side of school change: Reform, resistance, and the real-life problems of innovation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Pedagogy of hope: Reliving pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Galaif E. Suicidality, depression, and alcohol use among adolescents: A review of empirical findings. International journal of adolescent medicine and health. 2007;19(1):27–35. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2007.19.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Coll CT, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, et al. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67(5):1891–1914. doi: 10.2307/1131600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginwright S, Noguera P, Cammarota J, editors. Beyond resistance! Youth activism and community change: New democratic possibilities for practice and policy for America’s youth. New York: Routledge; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Granger RC. Creating the conditions linked to positive youth development. New Directions for Youth Development. 2002;95:149–164. doi: 10.1002/yd.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory A, Weinstein RS. The discipline gap and African Americans: Defiance or cooperation in the high school classroom. Journal of School Psychology. 2008;46(4):455–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helitzer D, Yoon SJ, Wallerstein N, Garcia-Velarde LD. The role of process evaluation in the training of facilitators for an adolescent health education program. Journal of School Health. 2000;70(4):141–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb06460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden DJ, Crankshaw E, Nimsch C, Hinnant LW, Hund L. Quantifying the impact of participation in local tobacco control groups on the psychological empowerment of involved youth. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31(5):615–628. doi: 10.1177/1090198104268678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B, Checkoway B, Schulz A, Zimmerman M. Health education and community empowerment: Conceptualizing and measuring perceptions of individual, organizational, and community control. Health Education Quarterly. 1994;21(2):149–170. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz A, EA P, Becker A, Alllen A, Guzman JR. Critical issues in developing and following community based participatory research principles. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, L., Parra-Medina, D., Hilfinger Messias, D., & McLoughlin, K. (2006). Toward a critical social theory of youth empowerment. Journal of Community Practice, 14(1–2), 31–55.

- Kirshner B. Supporting youth participation in school reform: Preliminary notes from a university-community partnership. Children Youth and Environments. 2007;17(2):354–363. [Google Scholar]

- Kozol J. Savage inequalities: Children in America’s schools. New York, NY: HarperCollins; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Walker K, Pearce N. A comparison of youth-driven and adult-driven youth programs: Balancing inputs from youth and adults. Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;33(1):57–74. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little JW, McLaughlin M. Teachers’ work: Individuals, colleagues, and contexts. New York, NY: Teachers College Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- London J. Youth REP: Step by step: An introduction to youth-led evaluation and research. Oakland, CA: Youth in Focus; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- London, J., Zimmerman, K., & Erbstein, N. (2003). Youth-led research and evaluation: Tools for youth, organizational, and community development. New Directions in Evaluation, 98, 33–45.

- Lortie D. School teacher: A sociological study. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Coatsworth JD. The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments. American Psychologist. 1998;53:205–220. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mediratta K, Shah S, McAlister S, Fruchter N, Mokhtar C, Lockwood D. Organized communities, stronger schools: A preview of research findings. Providence, RI: Brown University; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Midgley C, Feldlaufer H. Students’ and teachers’ decision-making fit before and after the transition to junior high school. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1987;7(2):225–241. doi: 10.1177/0272431687072009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra DL. The significance of students: Can increasing student voice in schools lead to gains in youth development? Teachers College Record. 2004;106(4):651–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9620.2004.00354.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell E. Six summers of YPAR: Learning, action, and change in urban education. In: Cammarota J, Fine M, editors. Revolutionizing education: Youth participatory action research in motion. New York: Routledge; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, S. (1996). Lessons from students on creating a chance to dream. Harvard Education Review.

- Ozer EJ, Cantor JP, Cruz GW, Fox B, Hubbard E, Moret L. The diffusion of youth-led participatory research in urban schools: The role of the prevention support system in implementation and sustainability. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41(3):278–289. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Hamre BK, Haynes NJ, Mintz S, La Paro KM. Classroom assessment scoring system (CLASS) manual: Middle/secondary version pilot. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport J, Swift C, Hess R. Studies in empowerment: Steps toward understanding and action. New York: Haworth; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason SB. Revisiting “the culture of the school and the problem of change”. New York, NY: Teachers College Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schensul JL, Berg MJ, Sydlo S. Core elements of participatory action research for educational empowerment and risk prevention with urban youth. Practicing Anthropology. 2004;26(2):5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Shor I. When students have the power: Negotiating authority in critical pedagogy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons R. Moving into adolescence: The impact of pubertal change and school context. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Skiba RJ, Michael RS, Nardo AC, Peterson RL. The color of discipline: Sources of racial and gender disproportionality in school punishment. The Urban Review. 2002;34(4):317–342. doi: 10.1023/A:1021320817372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, M. B., Dupree, D., & Hartmann, T. (1997). A phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST): A self-organization perspective in context. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 817–833 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Spencer MB, Fegley SG, Harpalani V. A theoretical and empirical examination of identity as coping: Linking coping resources to the self processes of African American youth. Applied Developmental Science. 2003;7(3):181–188. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0703_9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suleiman A, Soleimanpour S, London J. Youth action for health through youth-led research. Journal of Community Practice. 2006;14(1/2):125–145. doi: 10.1300/J125v14n01_08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sydlo SJ, Schensul JJ, Owens DC, Brase MK, Wiley KN, Berg MJ, et al. Participatory action research curriculum for empowering youth. Hartford, CT: The Institute for Community Research; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Trickett EJ, Todd DM. The high school culture: An ecological perspective. Theory into Practice. 1972;11(1):28–37. doi: 10.1080/00405847209542366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky LS. Mind and society: The development of higher mental processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, N., Sanchez, V., & Velarde, L. (2004). Freirian praxis in health education and community organizing: A case study of an adolescent prevention program. In M. Minkler (Ed.), Community organizing & community building for health (2nd ed.). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Wandersman A, Duffy J, Flaspohler P, Noonan R, Lubell K, Stillman L, et al. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: The interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41(3–4):171–181. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9174-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]