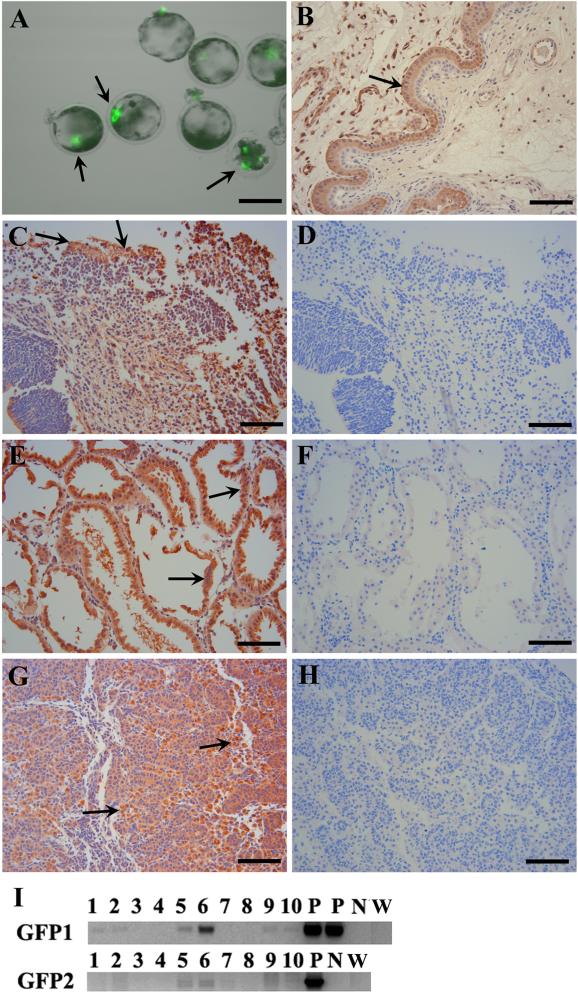

Multipotent skin-derived progenitors (SKPs) are neural crest derived and can be isolated from both embryonic and adult skin in humans, rodents and pigs1,2. The SKPs are capable of generating both neural and mesodermal progeny in vitro: neurons, Schwann cells, adipocytes, osteocytes, and chondrocytes, thus exhibiting properties similar to embryonic neural crest stem cells3. However, SKPs show distinct transcriptional profiles when compared to neural stem cells in the central nervous system and skin derived fibroblast, indicating a novel type of multipotent stem cells derived from skin. The SKPs are derived from hair follicle progenitors and exhibit adult dermal stem cell properties, contributing to dermal maintenance, would-healing, and hair follicle morphogenesis4. Transplantation experiments demonstrate that labeled murine SKP spheres can differentiate into dorsal root ganglia and autonomic ganglia when integrated into chick embryos, showing their neural potential in vivo5. However, it is still unclear whether SKPs can differentiate into neural and mesodermal lineages in developing mammalian embryos. Isolated porcine SKPs from embryonic and adult porcine skin have demonstrated their neural and mesodermal potency in vitro1,6. Since swine are an important model for human medicine and are a potential resource of tissue for xenotransplantation7 we addressed the in vivo differentiation of SKPs by injecting enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)-tagged8 porcine SKP cells into early embryos. Porcine SKP spheres were derived from the back skin of day 45 eGFP transgenic fetuses and dispersed into single cells by using Accumax solution (Sigma). Then 10-15 SKP cells were injected into the center of a peri-morula stage embryo. The injected embryos were cultured in PZM3 medium overnight at 38.5 °C in 5% CO2 in air and the next day transferred to the oviduct of a surrogate on day 4 of her estrous cycle8. The integration of SKP cells within the embryos were visualized by eGFP fluorescence before embryos transfer (Figure 1A). In total, we injected 416 embryos and performed 6 embryos transfers and produced two fetuses on day 45 of gestation (Supplemental Table 1). Various tissues (placenta, brain, skin, liver, trunk, kidneys and genital ridge) were collected and parts of tissues were stabilized immediately in RNAlater RNA Stabilization Reagent (Qiagen). Genomic DNA was extracted by using an AllPrep DNA/RNA mini kit (Qiagen). PCR was performed by using GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega). To exclude any potential false positive PCR results, two sets of eGFP primers (Supplemental Table 2) were used. The two eGFP bands were found in genomic DNA from both brain and kidney (Figure 1I). It may also appear in genital ridge because kidney and genital ridge are bound together at this developmental stage and a clear demarcation could not be determined. Moreover, no eGFP bands appeared in wild-type porcine genomic DNA (Figure 1I). Next we performed immunohistochemistry to confirm the eGFP expression in these tissues. Additional fetal tissues were fixed, embedded, sectioned and placed on plus charge slides. Sample slides were incubated with primary anti-eGFP antibody (1:400, Abcam) for 1 h, washed, and then with MACH 2 HPR-polymer secondary antibody (1:1000, Biocare Medical) for 30 min. Romulin Red (Biocare Medical) was used as chromogen for 10 min. Slides were then counterstained in CAT Hematoxylin for 5 min, washed, dehydrated and coverslipped. We found that the eGFP positive cells were dispersed in brain, kidney and genital ridges (Figure 1B-H). These results show that porcine SKP cells can develop into neural (brain) and mesodermal lineages (kidney and genital ridge) in vivo. Chimera production is widely used to test the pluripotency of embryonic stem (ES) cells and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Unlike ES or iPS cells, multipotent neural stem cells could not participate in development to form chimeric embryos in rodents9. However, a few reports indicate that multipotent stem cells could give rise to cells of multiple germ layers10-11. For instance, adult neural stem cells can contribute to the formation of chimeric chick and mouse embryos and generate cells of all three germ layers. Since SKP cells have been widely demonstrated to be multipotent and can differentiate into neural and mesodermal progeny in vitro and in transplantation experiments, it raises the question on the integration and differentiation of SKPs into embryonic tissues in vivo. Our study shows that porcine SKP cells can also contribute to neural (brain) and mesodermal (kidney) progeny in vivo, implying that the developmental potential of SKPs may not be as limited as expected before. SKPs are considered to have neural crest origin and share similar characteristics with neural crest stem cells in the peripheral nervous system; whereas we found that SKPs could also produce neural cells in the brain which belongs to the central nervous system. Although the early embryo may reprogram SKPs into a more pluripotent state, our data at least suggest the feasibility of converting skin into neural cells in brain and kidney cells. Together with other in vivo and in vitro findings, our data will strengthen the possibility of SKPs being used as a therapeutic resource for disease modeling and regenerative medicine in the future. In addition, SKP cells may potentially integrate into germ cell lines as eGFP positive SKP cells appeared in the developing kidney and genital ridge. Although it is too early to conclude that SKP cells can produce live chimeric pigs, it is encouraging to reprogram skin into kidney and brain in developing porcine embryos, implying a broad developmental potency of porcine SKPs.

Figure 1.

Contribution of porcine SKPs into neural and mesodermal lineages. (A) eGFP expression in injected day 5 IVF embryos 24 h post injection. (B) Positive control for anti-eGFP antibody: the section was from a uterus where placenta tissue was GFP positive (arrow) while epithelial endometrium was eGFP negative. This control fetus was created by nuclear transfer with eGFP transgenic donor cells. (C-H) Immunofluorescent staining of brain (C), kidney (E) and genital ridge (G) of chimeric fetuses. The corresponding negative controls with only secondary antibody were shown: brain (D), kidney (F) and genital ridge (H). The arrows show representative eGFP positive cell areas. (I) PCR results using genomic DNA from various tissues: brain (1-2), skin (3-4), kidney + genital ridge (5-6), liver (7-8) and body trunk (9-10). P: positive controls using the plasmid pEGFP-N1 as the template; N: negative control without template. W: wild-type porcine genomic DNA. GFP1 and GFP2 are different primer sets (Table 2). One fetus is in lanes 1, 3, 5, 7 & 9; while the other fetus is in lanes 2, 4, 6, 8 & 10. Scale bars: 100 μm (A); 50 μm (B-H).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from NIH National Center for Research Resources (R01RR013438) and Food for the 21st Century at the University of Missouri.

References

- 1.Zhao M, et al. Cloning Stem Cells. 2009;11:111–22. doi: 10.1089/clo.2008.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toma JG, et al. Stem Cells. 2005;23:727–37. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunt DP, et al. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2009;20:522–30. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biernaskie J, et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:610–23. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandes KJ, et al. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1082–93. doi: 10.1038/ncb1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lermen D, et al. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prather RS. Cloning Stem Cells. 2007;9:17–20. doi: 10.1089/clo.2006.0085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitworth KM, et al. Mol Reprod Dev. 2009;76:490–500. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Amour KA, et al. PNAS. 2003;100(Suppl 1):11866–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834200100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mezey E, et al. Science. 2000;290:1779–82. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang Y, et al. Nature. 2002;418:41–9. doi: 10.1038/nature00870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.